Faisal I of Iraq

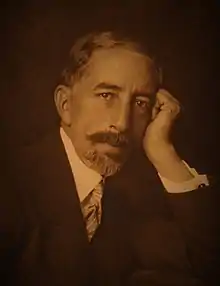

Faisal I bin Al-Hussein bin Ali Al-Hashemi (Arabic: فيصل الأول بن الحسين بن علي الهاشمي, Faysal el-Evvel bin al-Ḥusayn bin Alī el-Hâşimî; 20 May 1885[1][2][4] – 8 September 1933) was King of the Arab Kingdom of Syria or Greater Syria in 1920, and was King of Iraq from 23 August 1921 until his death. He was the third son of Hussein bin Ali, the Grand Emir and Sharif of Mecca, who was proclaimed as King of the Arabs in June 1916.

| Faisal I فيصل الأول | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

King Faisal I of Iraq and Syria | |||||

| King of Iraq | |||||

| Reign | 23 August 1921 – 8 September 1933 | ||||

| Predecessor | Military occupation | ||||

| Successor | Ghazi I | ||||

| Prime Ministers | See list

| ||||

| King of Syria | |||||

| Reign | 8 March 1920 – 24 July 1920 | ||||

| Predecessor | Military occupation | ||||

| Successor | Monarchy abolished | ||||

| Prime Ministers | See list

| ||||

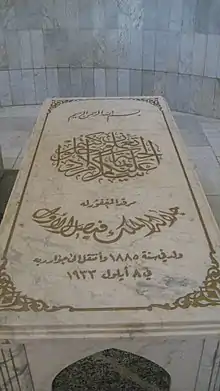

| Born | 20 May 1885[1][2] Mecca, Hejaz Vilayet, Ottoman Empire[1][2] | ||||

| Died | 8 September 1933 (aged 48) Bern, Switzerland | ||||

| Burial | Royal Mausoleum, Adhamiyah | ||||

| Spouse | Huzaima bint Nasser | ||||

| Issue |

| ||||

| |||||

| House | Hashemite | ||||

| Father | Hussein bin Ali, King of Hejaz | ||||

| Mother | Abdiyah bint Abdullah | ||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam[3] | ||||

He was a 38th-generation direct descendant of Muhammad, as he belonged to the Hashemite family.

Faisal fostered unity between Sunni and Shiite Muslims to encourage common loyalty and promote pan-Arabism in the goal of creating an Arab state that would include Iraq, Syria and the rest of the Fertile Crescent. While in power, Faisal tried to diversify his administration by including different ethnic and religious groups in offices. However, Faisal's attempt at pan-Arab nationalism possibly contributed to the isolation of certain groups.

Early life

Faisal was born in Mecca, Ottoman Empire[2] (in present-day Saudi Arabia), in 1885,[2] the third son of Hussein bin Ali, the Grand Sharif of Mecca. He grew up in Istanbul and learned about leadership from his father. In 1913, he was elected as representative for the city of Jeddah for the Ottoman parliament.

Following the Ottoman Empire's declaration of war against the Entente in December 1914, Faisal's father sent him on a mission to Constantinople to discuss the Ottomans' request for Arab participation in the war. Along the way Faisal visited Damascus and met with representatives of the Arab secret societies al-Fatat and Al-'Ahd. After visiting Constantinople Faisal returned to Mecca via Damascus where he again met with the Arab secret societies, received the Damascus Protocol, and joined with the Al-Fatat group of Arab nationalists.

World War I and the Great Arab Revolt

On 23 October 1916 at Hamra in Wadi Safra, Faisal met Captain T. E. Lawrence, a junior British intelligence officer from Cairo. Lawrence, who envisioned an independent post-war Arabian state, sought the right man to lead the Hashemite forces and achieve this.[5] In 1916–18, Faisal headed the Northern Army of the rebellion that confronted the Ottomans in what was to later become western Saudi Arabia, Jordan and Syria.[6] In 1917, Faisal, desiring an empire for himself instead of conquering one for his father, attempted to negotiate an arrangement with the Ottomans under which he would rule the Ottoman vilayets of Syria and Mosul as an Ottoman vassal.[7] In December 1917 Faisal contacted General Djemal Pasha declaring his willingness to defect to the Ottoman side provided they would give him an empire to rule, saying the Sykes–Picot agreement had disillusioned him in the Allies and he now wanted to work with his fellow Muslims.[8] Only the unwillingness of the Three Pashas to subcontract ruling part of the Ottoman Empire to Faisal kept him loyal to his father when it finally dawned on him that the Ottomans were just trying to divide and conquer the Hashemite forces.[7] In his book Seven Pillars of Wisdom, Lawrence sought to put the best gloss on Faisal's double-dealing as it would contradict the image he was seeking to promote of Faisal as a faithful friend of the Allies betrayed by the British and the French, claiming that Faisal was only seeking to divide the "nationalist" and "Islamist" factions in the ruling Committee of Union and Progress (CUP).[9] The Israeli historians Efraim Karsh and his wife Inari wrote that the veracity of Lawrence's account is open to question given that the major dispute within the CUP was not between the Islamist Djemal Pasha and the nationalist Mustafa Kemal as claimed by Lawrence, but rather between Enver Pasha and Djemal Pasha.[10] In the spring of 1918, after Germany launched Operation Michael on 21 March 1918, which appeared for a time to foreordain the defeat of the Allies, Faisal again contacted Djemal Pasha asking for peace provided that he be allowed to rule Syria as an Ottoman vassal, which Djemal confident of victory declined to consider.[10] After a 30-month-long siege, he conquered Medina, defeating the defence organised by Fakhri Pasha and looting the city. Emir Faisal also worked with the Allies during World War I in their conquest of Greater Syria and the capture of Damascus in October 1918. Faisal became part of a new Arab government at Damascus, formed after the capture of that city in 1918. Emir Faisal's role in the Arab Revolt was described by Lawrence in Seven Pillars of Wisdom. However, the accuracy of that book, not least the importance given by the author to his own contribution during the Revolt, has been criticized by some historians, including David Fromkin.

Post World War I

Participation in peace conference

In 1919, Emir Faisal led the Arab delegation to the Paris Peace Conference and, with the support of the knowledgeable and influential Gertrude Bell, argued for the establishment of independent Arab emirates for the predominantly Arab areas previously held by the Ottoman Empire.

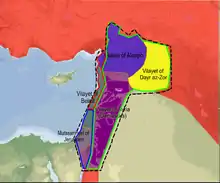

Greater Syria

British and Arab forces took Damascus in October 1918, which was followed by the Armistice of Mudros. With the end of Turkish rule that October, Faisal helped set up an Arab government, under British protection, in Arab controlled Greater Syria. In May 1919, elections were held for the Syrian National Congress, which met the following month.

Faisal–Weizmann Agreement

On 4 January 1919, Emir Faisal and Dr. Chaim Weizmann, President of the Zionist Organization,[11] signed the Faisal–Weizmann Agreement for Arab-Jewish Cooperation, in which Faisal conditionally accepted the Balfour Declaration, an official declaration on behalf of the British government by Arthur Balfour, promising British support to the development of a Jewish homeland in Palestine.[12] Once Arab states were granted autonomy from the European powers, years after the Faisal-Weizmann Agreement, and these new Arab nations were recognized by the Europeans, Weizmann argued that since the fulfillment was kept eventually, the agreement for a Jewish homeland in Palestine still held.[13] In truth, however, this hoped-for partnership had little chance of success and was a dead letter by late 1920. Faisal had hoped that Zionist influence on British policy would be sufficient to forestall French designs on Syria, but Zionist influence could never compete with French interests. At the same time Faisal failed to enlist significant sympathy among his Arab elite supporters for the idea of a Jewish homeland in Palestine, even under loose Arab suzerainty.

Following the decisions taken by the San Remo conference in April 1920, on 13 May 1920, Lord Allenby forwarded to the British War Cabinet, a letter from Faisal which stated his opposition to the Balfour proposal to establish a homeland for the Jews in Palestine.[14][15]

King of Syria and Iraq

On 7 March 1920, Faisal was proclaimed King of the Arab Kingdom of Syria (Greater Syria) by the Syrian National Congress government of Hashim al-Atassi. In April 1920, the San Remo conference gave France the mandate for Syria, which led to the Franco-Syrian War. In the Battle of Maysalun on 24 July 1920, the French were victorious and Faisal was expelled from Syria.

In March 1921, at the Cairo Conference, the British decided that Faisal was a good candidate for ruling the British Mandate of Iraq because of his apparent conciliatory attitude towards the Great Powers and based on advice from T. E. Lawrence (more commonly known as Lawrence of Arabia). But, in 1921, few people living in Iraq even knew who Faisal was or had ever heard his name. With help of British officials, including Gertrude Bell, he successfully campaigned among the Arabs of Iraq and won over the popular support of the minority Sunni. However, the Shia majority were lukewarm about Faisal, and his appearance at the Shia port of Basra was met with indifference.[16]

The British government, mandate holders in Iraq, were concerned at the unrest in the colony. They decided to step back from direct administration and create a monarchy to head Iraq while they maintained the mandate. Following a plebiscite showing 96% in favour, Faisal agreed to become king. On 23 August 1921, he was made king of Iraq. Iraq was a new entity created out of the former Ottoman vilayets (provinces) of Mosul, Baghdad and Basra. Ottoman vilayets were usually named after their capital, and thus the Basra vilayet was southern Iraq. Given this background, there was no sense of Iraqi nationalism or even Iraqi national identity when Faisal took his throne.[17] Anecdotally, the band present played God Save the King, as Iraq did not yet have a national anthem and would not have one until 1932.[18] During his reign as King, Faisal encouraged pan-Arab nationalism that envisioned ultimately bringing the French mandates of Syria and Lebanon together with the British mandate of Palestine under his rule. Faisal was keenly aware that his power-base was with the Sunni Arabs of Iraq, who comprised a minority.[19] By contrast, if Syria, Lebanon and Palestine were incorporated into his realm, then the Sunni Arabs would comprise the majority of his subjects, making the Arab Shiites and the Kurds of Iraq into minorities.[19] Furthermore, the Arab Shiites of Iraq had traditionally looked towards Persia for leadership, and the rallying cry of Pan-Arabism might unite the Arab Sunnis and Shiites around a common sense of Arab identity.[20] In Iraq, the majority of the Arabs were Shiites who had not responded to the call for Sharif Hussein to join the "Great Arab Revolt" as the Sharif was a Sunni from the Hejaz, thus making him a double outsider.[21] Rather than risk the wrath of the Ottomans on behalf of an outsider like Hussein, the Shia of Iraq had ignored the Great Arab Revolt.[21] In the Ottoman Empire, the state religion was Sunni Islam and the Shiites had been marginalized for their religion, making the Shia population poorer and less educated than the Sunni population.

Faisal encouraged an influx of Syrian exiles and office-seekers to cultivate better Iraqi-Syrian relations. In order to improve education in the country Faisal employed doctors and teachers in the civil service and appointed Sati' al-Husri, the ex-Minister of Education in Damascus, as his director of the Ministry of Education. This influx resulted in much native resentment towards Syrians and Lebanese in Iraq.[22] The tendency of the Syrian emigres in the education ministry to write and issue school textbooks glorying the Umayyad Caliphate as the "golden age" of the Arabs together with the highly dismissive remarks about the Imam Ali gave great offense in the Shiite community in Iraq, prompting protests and leading Faisal to withdraw the offending textbooks in 1927 and again in 1933 when they were reissued.[22] Faisal himself was a tolerant man, proclaiming himself a friend of the Shiite, Kurdish and Jewish communities in his realm, and in 1928 criticized the policy of some of his ministers of seeking to fire all Jewish Iraqis from the civil service, but his policy of promoting pan-Arab nationalism to further his personal and dynastic ambitions proved to be a disruptive force in Iraq as it drew a wedge between the Arab and Kurdish communities.[23] Faisal's policy of equating wataniyya ("patriotism" or in this case Iraqiness) with being Arab marginalized the Kurds who feared that they had no place in an Arab-dominated Iraq, indeed in a state that equated being Iraqi with being Arab.[23]

Faisal also developed desert motor routes from Baghdad to Damascus, and Baghdad to Amman. This led to a great interest in the Mosul oilfield and eventually to his plan to build an oil pipeline to a Mediterranean port, which would help Iraq economically. This also led to an increase in Iraq's desire for more influence in the Arab East. During his reign, Faisal made great effort to build Iraq's army into a powerful force. He attempted to impose universal military service in order to achieve this, but this failed. Some see this as part of his plan to advance his pan-Arab agenda.

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

During the Great Syrian Revolt against French rule in Syria, Faisal was not particularly supportive of the rebels partly because of British pressure, partly because of his own cautious nature, and mainly because he had reason to believe that the French were interested in installing a Hashemite to govern Syria on their behalf.[24] In 1925, after the Syrian Druze uprising, the French government began consulting Faisal on Syrian matters. He advised the French to restore Hashemite power in Damascus. The French consulted Faisal because they were inspired by his success as an imposed leader in Iraq. As it turned out, the French were merely playing Faisal along as they wished to give him the impression that he might be restored as king of Syria to dissuade him from supporting the Syrian rebels, and once they crushed the Syrian revolt, they lost interest in having a Hashemite rule Syria.[25]

In 1929, when bloody rioting broke out in Jerusalem between the Arab and Jewish communities, Faisal was highly supportive of the Arab position and pressured the British for a pro-Arab solution of the Palestine crisis.[26] In a memo stating his views on Palestine submitted to the British high commissioner Sir Hubert Young on 7 December 1929, Faisal accepted the Balfour Declaration, but only in the most minimal sense in that the declaration had promised a "Jewish national home".[27] Faisal stated he was willing to accept the Palestine Mandate as a "Jewish national home" to which Jews fleeing persecution around the world might go, but he was adamant that there be no Jewish state.[27] Faisal argued that the best solution was for Britain to grant independence to Palestine, which would be united in a federation led by his brother, the Emir Abdullah of Trans-Jordan, which would allow for a Jewish "national home" under his sovereignty.[28] Fasial argued that what was needed was a compromise under which the Palestinians would give up their opposition to Jewish immigration to Palestine in exchange for which the Zionists would give up their plans to one day create a Jewish state in the Holy Land.[27] Faisal's preferred solution to the "Palestine Question", which he admitted might not be practical at the moment, was for a federation that would unite Iraq, Syria, Lebanon and Palestine under his leadership.[27]

Faisal saw the Anglo-Iraqi Treaty of 1930 as an obstacle to his pan-Arab agenda, although it provided Iraq with a degree of political independence. He wanted to make sure that the treaty had a built-in end date because the treaty further divided Syria and Iraq, the former which was under French control, and the latter under British rule. This prevented unity between two major Arab regions, which were important in Faisal's pan-Arab agenda. Ironically, Arab nationalists in Iraq had a positive reception to the treaty because they saw this as progress, which seemed better than the Arab situation in Syria and Palestine. Faisal's schemes for a greater Iraqi-Syrian state under his leadership attracted much opposition from Turkey, which preferred to deal with two weak neighbors instead of one strong one, and from King Fuad of Egypt and Ibn' Saud, who both saw themselves as the rightful leaders of the Arab world.[27] When Nuri al-Said visited Yemen in May 1931 to ask the Imam Yahya Muhammad Hamid ed-Din if he was interested in joining the "Arab Alliance" under Faisal's leadership, the Imam replied with a confused look what would be the purpose of the "Arab Alliance" and to please explain the meaning of the phrase "Arab World", which he was unfamiliar with.[29]

In March 1932, just months before independence, Faisal wrote a memorandum where he complained about a lack of Iraqi national identity, writing:

Iraq is a kingdom ruled by a Sunni Arab government founded on the wreckage of Ottoman rule. This government rules over a Kurdish segment, the majority of which is ignorant, that includes persons with personal ambitions who lead it to abandon it [the government] under the pretext that it does not belong to their ethnicity. [The government also rules over] an ignorant Shiite majority that belongs to the same ethnicity of the government, but the persecutions that had befallen them as a result of Turkish rule, which did not enable them to take part in governance and exercise it, drove a deep wedge between the Arab people divided into these two sects. Unfortunately, all of this made this majority, or the persons who harbor special aspirations, the religious among them, the seekers of posts without qualification, and those who did not benefit materially from the new rule, to pretend that they are still being persecuted because they are Shiites.[30]

In 1932, the British mandate ended and Faisal was instrumental in making his country independent. On 3 October, the Kingdom of Iraq joined the League of Nations.

In August 1933, incidents like the Simele massacre caused tension between the United Kingdom and Iraq. Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald ordered High Commissioner Francis Humphrys to Iraq immediately upon hearing of the killing of Assyrian Christians. The British government demanded that Faisal stay in Baghdad to punish the guilty, whether Christian or Muslim. In response, Faisal cabled to the Iraqi Legation in London: "Although everything is normal now in Iraq, and in spite of my broken health, I shall await the arrival of Sir Francis Humphrys in Bagdad, but there is no reason for further anxiety. Inform the British Government of the contents of my telegram."[31]

In July 1933, right before his death, Faisal went to London where he expressed his alarm at the current situation of Arabs that resulted from the Arab-Jewish conflict and the increased Jewish immigration to Palestine, as the Arab political, social, and economic situation was declining. He asked the British to limit Jewish immigration and land purchases.

Death

King Faisal died of a heart attack on 8 September 1933 in Bern, Switzerland.[2] He was 48 years old at the time of his death. Faisal was succeeded on the throne by his eldest son Ghazi.

A square is named in his honour at the end of Haifa Street, Baghdad, where an equestrian statue of him stands. The statue was knocked down following the overthrow of the monarchy in 1958, but later restored.

Marriage and children

Faisal was married to Huzaima bint Nasser and had with her one son (King Ghazi) and three daughters:[32]

- Princess Azza bint Faisal.

- Princess Rajiha bint Faisal.

- Princess Raifia bint Faisal.

- Ghazi, King of Iraq, born 1912 died 4 April 1939, married his first cousin, Princess Aliya bint Ali, daughter of King Ali of Hejaz.

Film

Faisal has been portrayed on film at least three times: in David Lean's epic Lawrence of Arabia (1962), played by Alec Guinness; in the unofficial sequel to Lawrence, A Dangerous Man: Lawrence After Arabia (1990), played by Alexander Siddig; and in Werner Herzog's Queen of the Desert (2015), played by Younes Bouab. On video, he was portrayed in The Adventures of Young Indiana Jones: Chapter 19 The Winds of Change (1995) by Anthony Zaki.

Ancestry

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- Faisal–Weizmann Agreement

- List of Syrian monarchs

- Timeline of Syrian history

- Battle of Maysalun

- Ali of Hejaz

- Abdullah I of Jordan

- Ghazi of Iraq

- Hussein of Hejaz

References

- "rulers.org". rulers.org. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- "britannica.com". britannica.com. 8 September 1933. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- IRAQ – Resurgence In The Shiite World – Part 8 – Jordan & The Hashemite Factors, APS Diplomat Redrawing the Islamic Map, 14 February 2005

- Allawi, Ali A. (2014). Faisal I of Iraq. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300127324.

- Lawrence, T.E. The Seven Pillars of Wisdom. Wordsworth Editions, 1997. p. 76.

- Faisal of Arabia, The Jerusalem Post

- Karsh, Efraim Islamic Imperialism A History, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006 pages 137–138

- Karsh, Efraim & Karsh, Inari The Empires of the Sand, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999 page 195.

- Karsh, Efraim & Karsh, Inari The Empires of the Sand, Cambridge: Harvard University Press,, 1999 page 196.

- Karsh, Efraim & Karsh, Inari The Empires of the Sand, Cambridge: Harvard University Press,, 1999 page 197.

- Caplan, Neil (1983). "Faisal Ibn Husain and the Zionists: A Re-examination with Documents". The International History Review. 5 (4): 561–614. ISSN 0707-5332. JSTOR 40105338.

- United Nations (8 July 1947). "Official records of the Second Session of the General Assembly". Archived from the original on 7 May 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- Official records of the Second Session of the General Assembly (A/364/Add.2 PV.21), United Nations, 8 July 1947 Archived 7 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Reagan, Bernard (1 January 2016). The Implementation of the Balfour Declaration and the British Mandate in Palestine: problems of conquest and colonisation at the nadir of British Imperialism (1917-1936) (pdf). University of Surrey, School of Arts and Humanities. p. 178. OCLC 1004745577. Retrieved 17 May 2021. (PhD thesis)

- Hardi, Mahdi Abdul (2017). Documents on Palestine. Vol. I. Jerusalem: PASSIA. p. 78.

- "Letters from Baghdad" documentary (2016) Directors: Sabine Krayenbühl, Zeva Oelbaum.

- Allawi, Ali Faisal I of Iraq, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014 pages 339–340.

- Rezonville (17 February 1931). "VI. King Faisal I - First Issue, 1927 & 1932 - rezonville.com". Rezonville.com. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- Masalha, N "Faisal's Pan-Arabism, 1921–33" pages 679–693 from Middle Eastern Studies, Volume 27, Issue # 4, October 1991 page 679.

- Masalha, N "Faisal's Pan-Arabism, 1921–33" pages 679–693 from Middle Eastern Studies, Volume 27, Issue # 4, October 1991 pages 679–680.

- Karsh, Efraim & Karsh, Inari The Empires of the Sand, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999 page 196.

- Masalha, N "Faisal's Pan-Arabism, 1921–33" pages 679–693 from Middle Eastern Studies, Volume 27, Issue # 4, October 1991 page 690.

- Masalha, N "Faisal's Pan-Arabism, 1921–33" pages 679–693 from Middle Eastern Studies, Volume 27, Issue # 4, October 1991 pages 690–691.

- Masalha, N "Faisal's Pan-Arabism, 1921–33" pages 679–693 from Middle Eastern Studies, Volume 27, Issue # 4, October 1991 page 681.

- Masalha, N "Faisal's Pan-Arabism, 1921–33" pages 679–693 from Middle Eastern Studies, Volume 27, Issue # 4, October 1991 page 682.

- Masalha, N "Faisal's Pan-Arabism, 1921–33" pages 679–693 from Middle Eastern Studies, Volume 27, Issue # 4, October 1991 pages 683–684.

- Masalha, N "Faisal's Pan-Arabism, 1921–33" pages 679–693 from Middle Eastern Studies, Volume 27, Issue # 4, October 1991 page 684.

- Masalha, N "Faisal's Pan-Arabism, 1921–33" pages 679–693 from Middle Eastern Studies, Volume 27, Issue # 4, October 1991 pages 684–685.

- Masalha, N "Faisal's Pan-Arabism, 1921–33" pages 679–693 from Middle Eastern Studies, Volume 27, Issue # 4, October 1991 pages 689–690.

- Osman, Khalil Sectarianism in Iraq: The Making of State and Nation Since 1920, London: Routledge, 2014 page 71

- Time, 28 August 1933

- "The Hashemite Royal Family". Jordanian Government. Archived from the original on 6 April 2019. Retrieved 29 November 2008.

- Kamal Salibi (15 December 1998). The Modern History of Jordan. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9781860643316. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- "Family tree". alhussein.gov. 1 January 2014. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

External links

- "Border Massacre". Time. 28 August 1933. Archived from the original on 22 November 2010. Retrieved 18 August 2009.

- "Death of Feisal". Time. 18 September 1933. Archived from the original on 9 October 2010. Retrieved 18 August 2009.

- "Dreaming in Arabic" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 January 2010. Retrieved 27 January 2010.

- "King Faisal of Iraq". Archived from the original on 25 October 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- Newspaper clippings about Faisal I of Iraq in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

Further reading

- Masalha, N. (October 1991). "Faisal's Pan-Arabism, 1921–33". Middle Eastern Studies. 27 (4): 679–693. doi:10.1080/00263209108700885. JSTOR 4283470.

- Simon, Reeva S. (June 1974). "The Hashemite 'Conspiracy': Hashemite Unity Attempts, 1921–1958". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 5 (3): 314–327. doi:10.1017/s0020743800034966. JSTOR 162381.

- Allawi, Ali A. (2014). Faisal I of Iraq. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12732-4.

- Tripp, Charles (2007). A History of Iraq (3 ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-87823-4.