Korean Empire

The Korean Empire (Korean: 대한제국; Hanja: 大韓帝國; RR: Daehan Jeguk; MR: Taehan Jeguk; lit. Great Korean Empire) was a Korean monarchical state proclaimed in October 1897 by Emperor Gojong of the Joseon dynasty. The empire stood until Japan's annexation of Korea in August 1910.

Great Korean Empire 대한제국 大韓帝國 Daehan Jeguk | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1897–1910 | |||||||||||

.svg.png.webp) Flag

Imperial Seal

| |||||||||||

| Motto: 광명천지 光明天地 "Let the land be enlightened" | |||||||||||

| Anthem: 대한제국 애국가 大韓帝國愛國歌 "Patriotic Hymn of the Great Korean Empire" (1902–1910) | |||||||||||

Emblem | |||||||||||

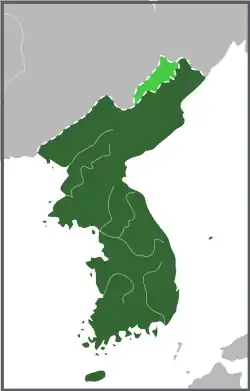

Territory of the Korean Empire 1903–1905. The disputed Gando and Samjiyon regions are shaded in lighter green. | |||||||||||

| Status | Sovereign state (1897–1905) Protectorate of Japan (1905–1910) | ||||||||||

| Capital | Hanseong (present-day Seoul) | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Korean | ||||||||||

| Religion | Confucianism, Buddhism, Shamanism, Taoism, Christianity, Cheondoism (recognized in 1907) | ||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Korean | ||||||||||

| Government | Unitary absolute monarchy | ||||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||||

• 1897–1907 | Gojong (first) | ||||||||||

• 1907–1910 | Sunjong (last) | ||||||||||

| Prime Minister[lower-alpha 1] | |||||||||||

• 1896–1898 | Yun Yong Seon (first) | ||||||||||

• 1907–1910 | Yi Wan-yong (last) | ||||||||||

| Legislature | Jungchuwon (until 1907) None (rule by decree) (from 1907) | ||||||||||

| Historical era | New Imperialism | ||||||||||

• Empire proclaimed | 13 October 1897 | ||||||||||

| 17 August 1899 | |||||||||||

• Eulsa Treaty | 17 November 1905 | ||||||||||

• Hague Secret Emissary Affair | July 1907 | ||||||||||

• Annexed by Japan | 29 August 1910 | ||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||

• 1900[1] | 17,082,000 | ||||||||||

| Currency | Yang (1897–1902) Won (1902–1910) | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | North Korea South Korea | ||||||||||

| Korean Empire | |

| Hangul | |

|---|---|

| Hanja | |

| Revised Romanization | Daehanjeguk |

| McCune–Reischauer | Taehanjeguk |

| IPA | [tɛ.ɦan.dʑe.ɡuk̚] |

| History of Korea |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

During the Korean Empire, Emperor Gojong oversaw the Gwangmu Reform, a partial modernization and westernization of Korea's military, economy, land system, and education system, and of various industries. In 1905, the Korean Empire became a protectorate of the Empire of Japan. After Japanese annexation in 1910, the Korean Empire was abolished.

History

Formation

.jpg.webp)

After the Japanese victory of First Sino-Japanese War, Joseon won independence from the Qing dynasty. Proclaiming an empire was seen by many politicians as a good way to maintain independence. At the request of many officials, Gojong of Korea proclaimed the Korean Empire.[2] In 1897, Gojong was coronated in Hwangudan.[3] Gojong named the new empire Dahan and changed the regnal year to Gwangmu, 1897 being the first year of Gwangmu.[4] The proclamation of the empire led to diplomatic friction with Qing dynasty but by avoiding imperial titles in diplomatic correspondence, the conflict was resolved.[5] Gojong made the Definition of the country in 1898, which gave the whole authority to the Emperor.[3]

Reforms

Rise of Civil Rights and the Independence Club

Even though all authority resided with the Emperor, popular influence in politics increased from the Joseon era. Many newspapers such as Tongnip Sinmun were established, promoting political awareness. Many organizations were established by people, including the Independence Club. Moreover, protests were not banned. People protested for reforms in Seoul.[6] The Independence Club tried to bring many reforms to the country to improve civil rights. The club established Junchuwon, which was a westernized senate of the Korean Empire.[7] In October 1898, the Independence Club made six requests to the emperor:[8]

- Neither officials nor people shall depend upon foreign aid, but shall do their best to strengthen and uphold the imperial power.

- All documents pertaining to foreign loans, the hiring of foreign soldiers, the granting of concessions, etc., in fact every document drawn up between the Korean government and a foreign party or firm, shall be signed and sealed by all the Ministers of State and the President of the Privy Council.

- Important offenders shall be punished only after they have been given a public trial and ample opportunity to defend themselves.

- To his Majesty shall belong the power to appoint Ministers, but in case a majority of the Cabinet disapproves of the Emperor's nominee he shall not be appointed.

- All sources of revenue and methods of raising taxes shall be placed under the control of the Finance Department, no other department, officer or corporation being allowed to interfere therewith; and the annual estimates and balances shall be made public.

- The existing laws and regulations shall be enforced without fear or favour.

The rival of the Independence Club, which was Sugu party, spread false rumors that the Independence Club was trying to depose Gojong of Korea and establish a Republic and make Bak Jeongyang President and Yun Chi-ho Vice President.[7] Because of the false rumor, the Independence Club was banned in December 1899. Despite popular protests, the Independence Club was not reformed.[6] The Hwanguk Club, which was the rival of the Independence Club rose to power, and some members of the Independence Club were arrested. The new cabinet was formed with many conservative politicians who did not want reforms.[7]

1888-1904

The Baby Riots of 1888 took place in the summer of 1888 in Joseon Korea.[9] Even though the Independence Club was banned, reform was not stopped. The Gwangmu Reform continued. However, the cabinet was radically changed. Officials such as Min Young-hwan, Han Kyu-seol, Yi Yong-ik, Shim Soon-taek, Yun Ung-nyeol, Shim Sang-hun, etc. led the reform, but most of these officials were conservative except Min Young-hwan, Han Kyu-seol, Yun Ung-nyeol. Yi Yong-ik and Shim Sang-hun were hated by the Independence Club.[7] These officials tried to reform the country conservatively.[10] New York Times reported that the new cabinet formed in early 1900s led by Yi Yong-ik was pro-Russian. There still were some ministers that were either pro-Japanese or pro-French. Pak Chesoon, who was the minister of foreign affair was pro-Japanese and Gwon Jung-hyeon, who was the minister of agriculture, and industry was pro-French. The cabinet tried to neutralize the Korean Empire.[11]

The new cabinet wanted to strengthen the power of the Emperor. This required more taxes from the citizens. Many minor taxes that were abolished by Gabo Reform were revived. These increased taxes enabled the Imperial Government to be rich enough to run the country.[10]

The new cabinet emphasized the independence of the country, leading to the enlargement of the Imperial Korean Army.[10] Colonel Dmitry Putyata and some officers were sent from Russia to Korea. However, Putyata had conflicts with Min Young-hwan, who was the former ambassador to Russia.[12] He returned to Russia on 26 November 1897 after assisting in the modernizing of the army.[13] In 1898, 10 more battalions were formed.[14] By sending troops, the Empire tried to protect its people. Officials were sent to Jiandao, where many Koreans lived.[10] By establishing an intelligence consisted of 200 men in 1903, stronger guards were accomplished.[15]

The new cabinet also wanted to make a modernized navy by buying ships. KIS Yangmu was the first ship to be bought, for 451,605 won.[15]

The government tried to industrialize the country by sending many students abroad to study industry. Many new technologies were brought in to Korea and many companies were established.[10] Formalizing land ownership records also enabled better land tax collection.[7]

These reforms were able to bring changes to the Korean Empire that made the country richer and stronger.

Tax revenue of Korean Empire during the Gwangmu Reform:[16]

| Year | 1897 | 1898 | 1899 | 1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903 | 1904 | 1905 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount of Tax Revenue in Won | 4,191,192 | 4,527,476 | 6,473,222 | 6,162,796 | 9,079,456 | 7,586,530 | 10,766,115 | 14,214,573 | 14,960,574 |

Foreign affairs

However, the problem of the Korean Empire was its foreign affairs. Despite its official neutrality, the country had many polices favored Russia. Russian intervention was frequent. Many Korean natural resources were sent to Russia.[7]

What the real intention of Russia was for Korea is still a mystery. According to a dispatch sent from Shanghai, Russia tried to make the Korean Empire a protectorate of Russian Empire.[17] But, the Czar of Russian Empire, Nicholas II of Russia, did not wanted to colonize Korea. In 1901, Nicholas told Prince Henry of Prussia "I do not want to seize Korea but under no circumstances can I allow Japan to become firmly established there. That will be a casus belli."[18]

Taft-Katsura Agreement and Russo Japanese War

Before the Russo-Japanese War, Korea tried to show her neutrality to different Western countries. On 27 January 1904, Russia, France, Germany, and England formally commended Korea's declaration of neutrality.[19]

On August 22, 1904, the first treaty between Japan and Korea, known as First Japan–Korea Convention, was signed. This allowed the creation of a Japanese garrison in Korea, the Japanese Korean Army.[20] The Taft–Katsura Agreement (also known as the Taft–Katsura Memorandum) was issued on July 17, 1905. It was not actually a secret pact or agreement between the United States and Japan, but rather a set of notes regarding discussions on U.S.-Japanese relations between members of the governments of the United States and Japan.[21] The Japanese Prime Minister Taro Katsura used the opportunity presented by Secretary of War William Howard Taft's stopover in Tokyo to extract a statement from Taft on the Korean question, in his capacity as a representative of the Roosevelt Administration.[22] Taft expressed in the Memorandum that a suzerain relationship with Japan guiding Korea would "contribute to permanent peace in the Far East".[22]

In September 1905, Russia and Japan signed the Treaty of Portsmouth, ending the Russo-Japanese War and firmly establishing Japan's influence in Korea. Secret diplomatic contacts were sent by the Gwangmu Emperor in the fall of 1905 to entities outside of Korea presenting Korea's desperate case to preserve their sovereignty, as normal diplomatic channels were no longer an option, due to the constant surveillance by the Japanese.[23]

The Eulsa Treaty

Until 1905, the Korean Empire was advancing due to reforms. However, things changed after the Eulsa Treaty. By the Taft–Katsura agreement, America and Japan gave mutual consent to the American colonization of Philippines and the Japanese colonization of Korea. Also through many treaties, Japan isolated Korea. Gojong of Korea was opposed to the Eulsa Treaty, but negotiations proceeded without him. There were eight ministers in the conference room. Prime Minister Han Kyu-seol, Minister of Army Yi Geun-taek, Minister of Interior Yi Ji-yong, Minister of Foreign Affairs Park Je-sun, Minister of Agriculture, Commerce and Industry Gwon Jung-hyeon, Minister of Finance Min Yeong-gi, and Minister of Justice Yi Ha-yeong were the Korean ministers in the conference room. Except for Han Kyu-seol, Min Yeoung-gi, and Yi Ha-young, all the ministers agreed with the treaty, which established a Japanese protectorate over Korea.[24] After the treaty was signed, the Waebu, which was the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Korean Empire, was dissolved. All the foreign affairs of the Korean Empire were handled by Tokyo.[25] Many embassies were recalled from Korea due to the treaty. On 1 February 1906, Itō Hirobumi, who led the Japanese treaty negotiations, became the first Japanese Resident-General of Korea.[26]

The Eulsa Treaty was deeply unpopular. Some, such as Min Young-hwan, committed suicide.[27] Many joined righteous armies and some even tried unsuccessfully assassinate the five Korean ministers who consented to the treaty.[28]

Emperor Gojong tried to show the unfairness of the Eulsa Treaty to the world. He sent many messages to monarchs of European countries such as Wilhelm II, George V, Nicholas II etc.[29] He sent Hulbert to repudiate the treaty.[30] In June 1906, Nicholas II secretly sent Gojong an invitation for the Hague Convention of 1907. He sent emissaries to the Hague in order to repudiate the Eulsa treaty. However, the emissaries were not accorded recognition.[31] The houses of Ye Wanyong were burned by the people. The Japanese Korean Army intervened to suppress public discontent. Forces of General Hasegawa garrisoned the palace. Some regiments of Imperial Korean Army was disarmed. The Pyeongyang Jinwidae, which was the elite unit of Imperial Korean Army, was disarmed.[32] These acts against the terms of the treaty led to the abdication of Gojong and Sunjong replaced him on 19 July 1907.[31]

As a Japanese protectorate

After Sunjong became emperor, the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1907 was signed. Under the treaty, more Japanese were employed in the Korean Government and started to intervene in Korean affairs more. Most of the Imperial Korean Army was dissolved.[33] These Japanese interventions fueled the righteous armies, local peasant militias fighting against the Japanese. These righteous armies fought against Japan with little success.[34] From 1909, the Japanese suppressed all of the righteous armies. Many members of the righteous armies fled to Manchuria or the rest of China to join the Independence Army.[35] Under Terauchi Masatake, Japan got ready to annex Korea. By the treaty of 22 August 1910, Korean Empire was annexed. The annexation was announced on 29 August 1910.[36]

Military

The Imperial Armed Forces (대한제국군) was the military of the Korean Empire.[37]

Composition

It was composed of the Imperial Korean Army, and the Imperial Korean Navy.

Organization

Succeeding the former Joseon Army and Navy, the Gwangmu Reform reorganized the military to a modern Western-style military. Unlike in the Joseon Dynasty, service was voluntary. It had a size of about 30,000, including soldiers and cadets.

Dissolution

The military disbanded on August 1, 1907, due to the Japan-Korea Treaty of 1907. Major Park Seung-hwan protested by committing suicide, and it sparked a revolt led by former imperial soldiers leading to the battle at Namdaemun Gate. Emperor Sunjong incorporated the remaining soldiers Imperial Guards until 1910, while others formed the foundations of the Righteous armies.

Economy

Some modern enterprises emerged in the Korean Empire, including some hand-operated machinery. These enterprises faced a crisis when Japanese products were imported into the country and the enterprises lacked capital intensity. Although limited banking infrastructure existed, it was not able to adequately support economic development.[38]

Nonetheless, the Korean Empire was able to have good economic growth. The GDP per capita of the Korean Empire was $850 in 1900, which was 26th in the world and 2nd in Asia.[39]

The economic progress of the Korean Empire was reflected in the secret report that Hayashi Gonsuke sent to Aoki Shūzō, indicating that the Korean Empire was becoming an economic participant on the global stage.[40]

Tax revenue of Korean Empire during 1895-1905:[16]

| Year | 1895 | 1896 | 1897 | 1898 | 1899 | 1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903 | 1904 | 1905 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount of Tax Revenue in Won | 4,557,587 | 4,809,410 | 4,191,192 | 4,527,476 | 6,473,222 | 6,162,796 | 9,079,456 | 7,586,530 | 10,766,115 | 14,214,573 | 14,960,574 |

Annual Expenditure of Korean Empire during 1895-1905:[41]

| Year | 1895 | 1896 | 1897 | 1898 | 1899 | 1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903 | 1904 | 1905 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount of Annual Expenditure in Won | 3,244,910 | 5,144,531 | 3,967,647 | 4,419,432 | 6,128,229 | 5,558,972 | 8,020,151 | 6,932,037 | 9,697,371 | 12,370,795 | 12,947,624 |

Diplomatic relationships

.svg.png.webp) Japan: 1876–1910

Japan: 1876–1910.svg.png.webp) United States: 1882–1905

United States: 1882–1905.svg.png.webp) Germany: 1883–1905

Germany: 1883–1905 United Kingdom: 1883–1905

United Kingdom: 1883–1905 Russia: 1884–1905

Russia: 1884–1905_crowned.svg.png.webp) Italy: 1884–1905

Italy: 1884–1905.svg.png.webp) France: 1886–1905

France: 1886–1905.svg.png.webp) Austria-Hungary: 1892–1905

Austria-Hungary: 1892–1905.svg.png.webp) China: 1899–1905

China: 1899–1905.svg.png.webp) Belgium: 1901–1905

Belgium: 1901–1905 Denmark: 1902–1905

Denmark: 1902–1905

Gallery

National seal

National seal.svg.png.webp) Coat of arms

Coat of arms Part of the old Russian legation building in Seoul. In 1896, King Gojong and his crown prince fled from the Gyeongbok Palace to the Russian legation in Seoul.

Part of the old Russian legation building in Seoul. In 1896, King Gojong and his crown prince fled from the Gyeongbok Palace to the Russian legation in Seoul. In 1900, Western attire became the official uniform for the Korean civil officials. Several years later, all Korean policemen were ordered to wear modernized uniforms.

In 1900, Western attire became the official uniform for the Korean civil officials. Several years later, all Korean policemen were ordered to wear modernized uniforms. Yi Yong-ik, Chief of the Bureau of Currency during the Korean Empire

Yi Yong-ik, Chief of the Bureau of Currency during the Korean Empire A streetcar in Seoul, 1903

A streetcar in Seoul, 1903 The headquarters of the Hanseong Electric Company

The headquarters of the Hanseong Electric Company Japanese infantry marching through Seoul during the Russo-Japanese War in 1904

Japanese infantry marching through Seoul during the Russo-Japanese War in 1904 Yi Beom-jin, an official and later independence fighter against the Japanese. He supported secret emissaries sent by Gojong to The Hague in 1907.

Yi Beom-jin, an official and later independence fighter against the Japanese. He supported secret emissaries sent by Gojong to The Hague in 1907. Three secret emissaries, Yi Tjoune, Yi Sang-seol and Yi Wi-jong, sent to The Hague, Netherlands in 1907 by the Gwangmu Emperor. (Hague Secret Emissary Affair)

Three secret emissaries, Yi Tjoune, Yi Sang-seol and Yi Wi-jong, sent to The Hague, Netherlands in 1907 by the Gwangmu Emperor. (Hague Secret Emissary Affair) Replica of the Stamp of Gojong used in his capacity as emperor

Replica of the Stamp of Gojong used in his capacity as emperor

In popular culture

- The King: Eternal Monarch explores an alternate reality where the country continues to the modern world.

- 2018 South Korean TV series Mr. Sunshine is set in the last days of the Korean empire.

- 2018 South Korean TV series The Last Empress portrays the modern-day Korean empire along with a dark secret of the imperial family leading to its demise.[42]

See also

- List of monarchs of Korea

- Korean Imperial Household

- Joseon

- Battle of Namdaemun

- National anthem of the Korean Empire

Footnotes

- Style: Naegak chongri daesin (1894–96); Ui jeong (1896–1905); Ui jeong daesin (1905–07); Chongri daesin (1907–10)

References

Citations

- 권태환 신용하 (1977). 조선왕조시대 인구추정에 관한 일시론 (in Korean).

- Yi 2012, pp. 189–190.

- Yi 2012, p. 187.

- "조선왕조실록". sillok.history.go.kr. Retrieved 2022-06-02.

- "한국사데이터베이스". db.history.go.kr. Retrieved 2022-06-05.

- Yi 2012, pp. 193–196.

- "대한제국(大韓帝國) - 한국민족문화대백과사전". encykorea.aks.ac.kr. Retrieved 2022-06-03.

- Hulbert 1906, p. 161-163.

- Neff, Robert D. Korea Through Western Eyes. Seoul: SNU Press, 2009.

- "광무개혁(光武改革) - 한국민족문화대백과사전". encykorea.aks.ac.kr. Retrieved 2022-06-05.

- "KOREAN CABINET CHANGES.; The Party Now in Power Said to be Pro-Russian -- Seoul a Hotbed of Intrigues". The New York Times. 1901-12-09. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-06-20.

- "한국사데이터베이스". db.history.go.kr. Retrieved 2022-06-05.

- "한국사데이터베이스". db.history.go.kr. Retrieved 2022-06-05.

- "한국사데이터베이스". db.history.go.kr. Retrieved 2022-06-05.

- "한국사데이터베이스". db.history.go.kr. Retrieved 2022-06-20.

- "한국사데이터베이스". db.history.go.kr. Retrieved 2022-03-12.

- "Russia's Intentions in Corea". The New York Times. 1896-02-18. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-06-19.

- Clark, Christopher (2012-09-27). The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914. Penguin Books Limited. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-7181-9295-2.

- Hulbert 1904, p. 77.

- "우리역사넷". contents.history.go.kr. Retrieved 2022-06-20.

- Nahm 1985, p. 9.

- Nahm 1985, p. 10.

- Kim 2006, p. 239.

- "을사조약(乙巳條約) - 한국민족문화대백과사전". encykorea.aks.ac.kr. Retrieved 2022-06-10.

- "한국사데이터베이스". db.history.go.kr. Retrieved 2022-06-14.

- "통감부(統監府) - 한국민족문화대백과사전". encykorea.aks.ac.kr. Retrieved 2022-06-10.

- "을사늑약". terms.naver.com (in Korean). Retrieved 2022-06-14.

- "을사조약반대운동(乙巳條約反對運動) - 한국민족문화대백과사전". encykorea.aks.ac.kr. Retrieved 2022-06-14.

- "빌헬름 2세는 고종을 '왕' 아닌 '황제'로 칭했다". 중앙일보 (in Korean). 2009-09-29. Retrieved 2022-06-20.

- "KOREA REPUDIATES TREATY.; Emperor Wires to Mr. Hulbert That Japan Obtained It by Force". The New York Times. 1905-12-13. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-06-20.

- "헤이그특사사건(─特使事件) - 한국민족문화대백과사전". encykorea.aks.ac.kr. Retrieved 2022-06-20.

- "Front Page 4 -- No Title; Attempt to Murder Ministers. Korean Regiment Disarmed. Crown Prince Now Emperor". The New York Times. 1907-07-21. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-06-20.

- "한일신협약(韓日新協約) - 한국민족문화대백과사전". encykorea.aks.ac.kr. Retrieved 2022-06-20.

- "정미의병(丁未義兵) - 한국민족문화대백과사전". encykorea.aks.ac.kr. Retrieved 2022-06-20.

- "남한폭도 대토벌작전(南韓暴徒 大討伐作戰) - 한국민족문화대백과사전". encykorea.aks.ac.kr. Retrieved 2022-06-20.

- "한일합병(韓日合倂) - 한국민족문화대백과사전". encykorea.aks.ac.kr. Retrieved 2022-06-20.

- Seth, Michael J. (2010-10-16). A History of Korea: From Antiquity to the Present. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7425-6717-7.

- Chu, Zin-oh. "독립협회와 대한제국의 경제정책 비 연구" (PDF). Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- "Countries Compared by Economy > GDP per capita in 1900. International Statistics at NationMaster.com". www.nationmaster.com. Retrieved 2022-01-30.

- 배, 영대 (2017-12-03). "1901년 서울은 이미 서양인도 감탄한 '근대적 대도시'". 중앙일보 (in Korean). Retrieved 2022-02-19.

- "한국사데이터베이스". db.history.go.kr. Retrieved 2022-03-12.

- "[왜냐면] '미스터 션샤인'과 구한말 한미관계 왜곡 / 최형익". Hankyoreh. 2018-08-20.

Sources

- Keltie, J.S., ed. (1900). The Statesman's Year Book: Statistical and Historical Annual of the States of the World for the Year 1900. New York: MacMillan.

- Dong-no Kim, John B. Duncan, Do-hyung Kim (2006), Reform and Modernity in the Taehan Empire (Yonsei Korean Studies Series No. 2), Seoul: Jimoondang Publishing Company

- Jae-gon Cho, The Industrial Promotion Policy and Commercial Structure of the Taehan Empire.

- Kim, Ki-Seok (Summer 2006). "Emperor Gwangmu's Diplomatic Struggles to Protect His Sovereignty before and after 1905". Korea Journal.

- Nahm, Andrew (October 1985). "The impact of the Taft-Katsura Memorandum on Korea: A reassessment". Korea Journal.

- Pratt, Keith L., Richard Rutt, and James Hoare. (1999). Korea: a historical and cultural dictionary, Richmond: Curzon Press. ISBN 9780700704637; ISBN 9780700704644; OCLC 245844259

- The Special Committee for the Virtual Museum of Korean History (2009), Living in Joseon Part 3: The Virtual Museum of Korean History-11, Paju: Sakyejul Publishing Ltd.

- Yi, Ha-kyoung (2012). "대한제국 시기 군주권 강화와 민권 확대 논의의 전개: 주권론을 중심으로; Power of King and the People in the Daehan Empire: Focusing on the Theory of Sovereignty" (PDF). Seoul National University: S-Space – via 서울대학교 한국정치연구소.

- Hulbert, Homer (1906). The Passing of Korea.

- Hulbert, Homer B. (1904). The Korea Review.