Passover

Passover, also called Pesach (/ˈpɛsɑːx, ˈpeɪ-/;[2] Biblical Hebrew: חַג הַפֶּסַח, romanized: Ḥag haPesaḥ), is a major Jewish holiday that celebrates the exodus of the Israelites from slavery in Egypt,[3] which occurs on the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Nisan, the first month of Aviv, or spring. The word Pesach or Passover can also refer to the Korban Pesach, the paschal lamb that was offered when the Temple in Jerusalem stood; to the Passover Seder, the ritual meal on Passover night; or to the Feast of Unleavened Bread. One of the biblically ordained Three Pilgrimage Festivals, Passover is traditionally celebrated in the Land of Israel for seven days and for eight days among many Jews in the Diaspora, based on the concept of yom tov sheni shel galuyot. In the Bible, the seven-day holiday is known as Chag HaMatzot, the feast of unleavened bread (matzoh).[4]

| Passover | |

|---|---|

A table set up for a Passover Seder | |

| Official name | Pesach – פסח (in Hebrew). |

| Observed by | Jews |

| Type | Jewish (religious and cultural) |

| Significance |

|

| Celebrations | Passover Seder |

| Begins | 15 Nisan |

| Ends | 21 Nisan (22 Nisan in traditional Diaspora communities) |

| Date | 15 Nisan, 16 Nisan, 17 Nisan, 18 Nisan, 19 Nisan, 20 Nisan, 21 Nisan, 22 Nisan |

| 2021 date | Sunset, 27 March – nightfall, 4 April[1] (8 days) |

| 2022 date | Sunset, 15 April – nightfall, 23 April[1] (8 days) |

| 2023 date | Sunset, 5 April – nightfall, 13 April[1] (8 days) |

| 2024 date | Sunset, 22 April – nightfall, 30 April[1] (8 days) |

| Related to | Shavuot ("Festival of Weeks") which follows 49 days from the second night of Passover. |

According to the Book of Exodus, God commands Moses to tell the Israelites to mark a lamb's blood above their doors in order that the Angel of Death will pass over them (i.e., that they will not be touched by the tenth plague, death of the firstborn). After the death of the firstborn Pharaoh, the Israelites were ordered to leave, taking whatever they want, and Moses was asked to bless him in the name of the Lord. The passage goes on to state that the Passover sacrifice recalls the time when God "passed over the houses of the Israelites in Egypt".[5] This story is recounted at the Passover meal in the form of the Haggadah, in fulfillment of the command "And thou shalt tell (Higgadata) thy son in that day, saying: It is because of that which the LORD did for me when I came forth out of Egypt."[6]

The wave offering of barley was offered at Jerusalem on the second day of the festival. The counting of the sheaves is still practiced, for seven weeks until the Feast of Weeks on the 50th day, the holiday of Shavuot.

Nowadays, in addition to the biblical prohibition of owning leavened foods for the duration of the holiday, the Passover Seder is one of the most widely observed rituals in Judaism.

Etymology

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

|

|

The Hebrew פֶּסַח is rendered as Tiberian [pɛsaħ] (![]() listen), and Modern Hebrew: [ˈpesaχ] Pesah, Pesakh. The verb pasàch (פָּסַח) is first mentioned in the Torah's account of the Exodus from Egypt,[7] and there is some debate about its exact meaning. The commonly held assumption that it means "He passed over" (פסח), in reference to God "passing over" (or "skipping") the houses of the Hebrews during the final of the Ten Plagues of Egypt, stems from the translation provided in the Septuagint (Ancient Greek: παρελευσεται, romanized: pareleusetai in Exodus 12:23,[7] and εσκεπασεν, eskepasen in Exodus 12:27.)[5] Targum Onkelos translates pesach as ve-yeiḥos (Hebrew: וְיֵחוֹס, romanized: we-yēḥôs) "he had pity" coming from the Hebrew root חסה meaning "to have pity".[8] Cognate languages yield similar terms with distinct meanings, such as "make soft, soothe, placate" (Akkadian passahu), "harvest, commemoration, blow" (Egyptian), or "separate" (Arabic fsh).[9]

listen), and Modern Hebrew: [ˈpesaχ] Pesah, Pesakh. The verb pasàch (פָּסַח) is first mentioned in the Torah's account of the Exodus from Egypt,[7] and there is some debate about its exact meaning. The commonly held assumption that it means "He passed over" (פסח), in reference to God "passing over" (or "skipping") the houses of the Hebrews during the final of the Ten Plagues of Egypt, stems from the translation provided in the Septuagint (Ancient Greek: παρελευσεται, romanized: pareleusetai in Exodus 12:23,[7] and εσκεπασεν, eskepasen in Exodus 12:27.)[5] Targum Onkelos translates pesach as ve-yeiḥos (Hebrew: וְיֵחוֹס, romanized: we-yēḥôs) "he had pity" coming from the Hebrew root חסה meaning "to have pity".[8] Cognate languages yield similar terms with distinct meanings, such as "make soft, soothe, placate" (Akkadian passahu), "harvest, commemoration, blow" (Egyptian), or "separate" (Arabic fsh).[9]

The term Pesach (Hebrew: פֶּסַח, Pesaḥ) may also refer to the lamb or goat which was designated as the Passover sacrifice (called the Korban Pesach in Hebrew). Four days before the Exodus, the Hebrews were commanded to set aside a lamb,[10] and inspect it daily for blemishes. During the day on the 14th of Nisan, they were to slaughter the animal and use its blood to mark their lintels and door posts. Before midnight on the 15th of Nisan they were to consume the lamb.

The English term "Passover" is first known to be recorded in the English language in William Tyndale's translation of the Bible,[11] later appearing in the King James Version as well. It is a literal translation of the Hebrew term.[12] In the King James Version, Exodus 12:23 reads:

For the LORD will pass through to smite the Egyptians; and when he seeth the blood upon the lintel, and on the two side posts, the LORD will pass over the door, and will not suffer the destroyer to come in unto your houses to smite you.[13]

Origins

The Passover ritual is widely thought to have its origins in an apotropaic rite, unrelated to the Exodus, to ensure the protection of a family home, a rite conducted wholly within a clan.[14] Hyssop was employed to daub the blood of a slaughtered sheep on the lintels and door posts to ensure that demonic forces could not enter the home.[15]

A further hypothesis maintains that once the Priestly Code was promulgated, the Exodus narrative took on a central function, as the apotropaic rite was, arguably, amalgamated with the Canaanite agricultural festival of spring which was a ceremony of unleavened bread, connected with the barley harvest. As the Exodus motif grew, the original function and symbolism of these double origins was lost.[16] Several motifs replicate the features associated with the Mesopotamian Akitu festival.[17] Other scholars, John Van Seters, J.B.Segal and Tamara Prosic disagree with the merged two-festivals hypothesis.[18]

Biblical narrative

In the Book of Exodus

In the Book of Exodus, the Israelites are enslaved in ancient Egypt. Yahweh, the god of the Israelites, appears to Moses in a burning bush and commands Moses to confront Pharaoh. To show his power, Yahweh inflicts a series of 10 plagues on the Egyptians, culminating in the 10th plague, the death of the first-born.

This is what the LORD says: "About midnight I will go throughout Egypt. Every firstborn son in Egypt will die, from the firstborn son of Pharaoh, who sits on the throne, to the firstborn of the slave girl, who is at her hand mill, and all the firstborn of the cattle as well. There will be loud wailing throughout Egypt – worse than there has ever been or ever will be again."

— Exodus 11:4–6

Before this final plague Yahweh commands Moses to tell the Israelites to mark a lamb's blood above their doors in order that Yahweh will pass over them (i.e., that they will not be touched by the death of the firstborn).

The biblical regulations for the observance of the festival require that all leavening be disposed of before the beginning of the 15th of Nisan.[19] An unblemished lamb or goat, known as the Korban Pesach or "Paschal Lamb", is to be set apart on 10th Nisan,[10] and slaughtered at dusk as 14th Nisan ends in preparation for the 15th of Nisan when it will be eaten after being roasted.[20] The literal meaning of the Hebrew is "between the two evenings".[21] It is then to be eaten "that night", 15th Nisan,[22] roasted, without the removal of its internal organs[23] with unleavened bread, known as matzo, and bitter herbs known as maror.[22] Nothing of the sacrifice on which the sun rises by the morning of the 15th of Nisan may be eaten, but must be burned.[24]

The biblical regulations pertaining to the original Passover, at the time of the Exodus only, also include how the meal was to be eaten: "with your loins girded, your shoes on your feet, and your staff in your hand; and ye shall eat it in haste: it is the LORD's passover".[25]

The biblical requirements of slaying the Paschal lamb in the individual homes of the Hebrews and smearing the blood of the lamb on their doorways were celebrated in Egypt. However, once Israel was in the wilderness and the tabernacle was in operation, a change was made in those two original requirements.[26] Passover lambs were to be sacrificed at the door of the tabernacle and no longer in the homes of the Jews. No longer, therefore, could blood be smeared on doorways.

The passover in other biblical passages

Called the "festival [of] the matzot" (Hebrew: חג המצות ḥag ha-matzôth) in the Hebrew Bible, the commandment to keep Passover is recorded in the Book of Leviticus:

In the first month, on the fourteenth day of the month at dusk is the LORD's Passover. And on the fifteenth day of the same month is the feast of unleavened bread unto the LORD; seven days ye shall eat unleavened bread. In the first day ye shall have a holy convocation; ye shall do no manner of servile work. And ye shall bring an offering made by fire unto the LORD seven days; in the seventh day is a holy convocation; ye shall do no manner of servile work.

— Leviticus 23:5–8 (JPS 1917 Version)

The sacrifices may be performed only in a specific place prescribed by God. For Judaism, this is Jerusalem.[27]

The biblical commandments concerning the Passover (and the Feast of Unleavened Bread) stress the importance of remembering:

- Exodus 12:14 commands, in reference to God's sparing of the firstborn from the Tenth Plague: "And this day shall be unto you for a memorial, and ye shall keep it a feast to the LORD; throughout your generations ye shall keep it a feast by an ordinance for ever."[28]

- Exodus 13:3 repeats the command to remember: "Remember this day, in which you came out of Egypt, out of the house of bondage, for by strength the hand of the LORD brought you out from this place."[29]

- Deuteronomy 16:12: "And thou shalt remember that thou wast a bondman in Egypt; and thou shalt observe and do these statutes".[30]

In 2 Kings 23:21–23 and 2 Chronicles 35:1–19, King Josiah of Judah restores the celebration of the Passover,[31] to a standard not seen since the days of the judges or the days of the prophet Samuel.[32]

Ezra 6:19–21 records the celebration of the passover by the Jews who had returned from exile in Babylon, after the temple had been rebuilt.[33]

In extra-biblical sources

Some of these details can be corroborated, and to some extent amplified, in extrabiblical sources. The removal (or "sealing up") of the leaven is referred to in the Elephantine papyri, an Aramaic papyrus from 5th century BCE Elephantine in Egypt.[34] The slaughter of the lambs on the 14th is mentioned in The Book of Jubilees, a Jewish work of the Ptolemaic period, and by the Herodian-era writers Josephus and Philo. These sources also indicate that "between the two evenings" was taken to mean the afternoon.[35] Jubilees states the sacrifice was eaten that night,[36] and together with Josephus states that nothing of the sacrifice was allowed to remain until morning.[37] Philo states that the banquet included hymns and prayers.[38]

Date and duration

The Passover begins on the 15th day of the month of Nisan, which typically falls in March or April of the Gregorian calendar. The 15th day begins in the evening, after the 14th day, and the seder meal is eaten that evening. Passover is a spring festival, so the 15th day of Nisan typically begins on the night of a full moon after the northern vernal equinox.[39] However, due to leap months falling after the vernal equinox, Passover sometimes starts on the second full moon after vernal equinox, as in 2016.

To ensure that Passover did not start before spring, the tradition in ancient Israel held that the lunar new year, the first day of Nisan, would not start until the barley was ripe, being the test for the onset of spring.[40] If the barley was not ripe, or various other phenomena[41] indicated that spring was not yet imminent, an intercalary month (Adar II) would be added. However, since at least the 4th century, the intercalation has been fixed mathematically according to the Metonic cycle.[42]

In Israel, Passover is the seven-day holiday of the Feast of Unleavened Bread, with the first and last days celebrated as legal holidays and as holy days involving holiday meals, special prayer services, and abstention from work; the intervening days are known as Chol HaMoed ("Weekdays [of] the Festival"). Jews outside the Land of Israel celebrate the festival for eight days. Reform and Reconstructionist Jews usually celebrate the holiday over seven days.[43][44][45] Karaites use a different version of the Jewish calendar, differing from that used with modern Jewish calendar by one or two days.[46] The Samaritans use a calendrical system that uses a different method from that current in Jewish practice, in order to determine their timing of feastdays.[47] In 2009, for example, Nisan 15 on the Jewish calendar used by Rabbinic Judaism corresponds to April 9. On the calendars used by Karaites and Samaritans, Abib or Aviv 15 (as opposed to 'Nisan') corresponds to April 11 in 2009. The Karaite and Samaritan Passovers are each one day long, followed by the six-day Festival of Unleavened Bread – for a total of seven days.[48]

Passover sacrifice

The main entity in Passover according to Judaism is the sacrificial lamb.[49] During the existence of the Tabernacle and later the Temple in Jerusalem, the focus of the Passover festival was the Passover sacrifice (Hebrew: korban Pesach), also known as the Paschal lamb, eaten during the Passover Seder on the 15th of Nisan. Every family large enough to completely consume a young lamb or wild goat was required to offer one for sacrifice at the Jewish Temple on the afternoon of the 14th day of Nisan,[50] and eat it that night, which was the 15th of Nisan.[51] If the family was too small to finish eating the entire offering in one sitting, an offering was made for a group of families. The sacrifice could not be offered with anything leavened,[52] and had to be roasted, without its head, feet, or inner organs being removed[53] and eaten together with unleavened bread (matzo) and bitter herbs (maror). One had to be careful not to break any bones from the offering,[54] and none of the meat could be left over by morning.[55]

Because of the Passover sacrifice's status as a sacred offering, the only people allowed to eat it were those who had the obligation to bring the offering. Among those who could not offer or eat the Passover lamb were an apostate,[56] a servant,[57] an uncircumcised man[58] a person in a state of ritual impurity, except when a majority of Jews are in such a state,[59] and a non-Jew. The offering had to be made before a quorum of 30.[60] In the Temple, the Levites sang Hallel while the priests performed the sacrificial service. Men and women were equally obligated regarding the offering (Pesahim 91b).

Today, in the absence of the Temple, when no sacrifices are offered or eaten, the mitzvah of the Korban Pesach is memorialized in the Seder Korban Pesach, a set of scriptural and Rabbinic passages dealing with the Passover sacrifice, customarily recited after the Mincha (afternoon prayer) service on the 14th of Nisan,[61] and in the form of the zeroa, a symbolic food placed on the Passover Seder Plate (but not eaten), which is usually a roasted shankbone (or a chicken wing or neck). The eating of the afikoman substitutes for the eating of the Korban Pesach at the end of the Seder meal (Mishnah Pesachim 119a). Many Sephardi Jews have the custom of eating lamb or goat meat during the Seder in memory of the Korban Pesach.

Removing all leaven (chametz)

Leaven, in Hebrew chametz (Hebrew: חמץ ḥamets, "leavening") is made from one of five types of grains[62] combined with water and left to stand for more than eighteen minutes. The consumption, keeping, and owning of chametz is forbidden during Passover. Yeast and fermentation are not themselves forbidden as seen for example by wine, which is required, rather than merely permitted. According to Halakha, the ownership of such chametz is also proscribed.[63]

Chametz does not include baking soda, baking powder or like products. Although these are defined in English as leavening agents, they leaven by chemical reaction, not by biological fermentation. Thus, bagels, waffles and pancakes made with baking soda and matzo meal are considered permissible, while bagels made with sourdough and pancakes and waffles made with yeast are prohibited.[64]

The Torah commandments regarding chametz are:

- To remove all chametz from one's home, including things made with chametz, before the first day of Passover[65] It may be simply used up, thrown out (historically, destroyed by burning), or given or sold to non-Jews.

- To refrain from eating chametz or mixtures containing chametz during Passover.[66]

- Not to possess chametz in one's domain (i.e. home, office, car, etc.) during Passover.[67]

Observant Jews spend the weeks before Passover in a flurry of thorough housecleaning, to remove every morsel of chametz from every part of the home. Jewish law requires the elimination of olive-sized or larger quantities of leavening from one's possession, but most housekeeping goes beyond this. Even the seams of kitchen counters are thoroughly cleaned to remove traces of flour and yeast, however small. Any containers or implements that have touched chametz are stored and not used during Passover.[68]

Some hotels, resorts, and even cruise ships across America, Europe, and Israel also undergo a thorough housecleaning to make their premises "kosher for Pesach" to cater to observant Jews.[69]

Interpretations for abstinence from leaven or yeast

Some scholars suggest that the command to abstain from leavened food or yeast suggests that sacrifices offered to God involve the offering of objects in "their least altered state", that would be nearest to the way in which they were initially made by God.[49][70] According to other scholars the absence of leaven or yeast means that leaven or yeast symbolizes corruption and spoiling.[49][71]

There are also variations with restrictions on eating matzah before Passover so that there will be an increased appetite for it during Passover itself. Primarily among Chabad Chassidim, there is a custom of not eating matzoh (flat unleavened bread) in the 30 days before Passover begins.[72] Others have a custom to refrain from eating matzah from Rosh Chodesh Nissan, while the halacha merely restricts one from eating matzah on the day before Passover.[73]

Sale of leaven

.jpg.webp)

Leaven or chametz may be sold rather than discarded, especially in the case of relatively valuable forms such as liquor distilled from wheat, with the products being repurchased afterward. In some cases, they may never leave the house, instead being formally sold while remaining in the original owner's possession in a locked cabinet until they can be repurchased after the holiday. Modern observance may also include sealing cabinets and drawers which contain "Chametz" shut by using adhesive tape, which serves a similar purpose to a lock but also shows evidence of tampering. Although the practice of selling "Chametz" dates back many years, some Reform rabbinical authorities have come to regard it with disdain – since the supposed "new owner" never takes actual possession of the goods.[74]

The sale of chametz may also be conducted communally via a rabbi, who becomes the "agent" for all the community's Jews through a halakhic procedure called a kinyan (acquisition). Each householder must put aside all the chametz he is selling into a box or cupboard, and the rabbi enters into a contract to sell all the chametz to a non-Jew (who is not obligated to celebrate the commandments) in exchange for a small down payment (e.g. $1.00), with the remainder due after Passover. This sale is considered completely binding according to Halakha, and at any time during the holiday, the buyer may come to take or partake of his property. The rabbi then re-purchases the goods for less than they were sold at the end of the holiday.[75]

Search for leaven

On the night of the fourteenth of Nisan, the night before the Passover Seder (after nightfall on the evening before Passover eve), Jews do a formal search in their homes known as bedikat chametz for any possible remaining leaven (chametz). The Talmudic sages instructed that a search for chametz be made in every home, place of work, or any place where chametz may have been brought during the year.[76] When the first Seder is on a Saturday night, the search is conducted on the preceding Thursday night (thirteenth of Nisan) as chametz cannot be burned during Shabbat.

The Talmud in Pesahim (p. 2a) derives from the Torah that the search for chametz be conducted by the light of a candle and therefore is done at night, and although the final destruction of the chametz (usually by burning it in a small bonfire) is done on the next morning, the blessing is made at night because the search is both in preparation for and part of the commandments to remove and destroy all chametz from one's possession.[76]

Blessing for search of chametz and nullification of chametz

Before the search is begun there is a special blessing. If several people or family members assist in the search then only one person, usually the head of that family recites the blessing having in mind to include everyone present:[76]

- Blessed are You, Hashem our God, King of the universe, Who has sanctified us with his commandments and has commanded us concerning the removal of chametz.

In Hebrew:

ברוך אתה י-הוה א-להינו מלך העולם אשר קדשנו במצותיו וצונו על בעור חמץ

(berūkh otah, Adoynoy E-lohaynū, melekh ha-‘ôlam, eser qedesh-nū be-mitsūtayu we-tsewinū ‘al be-ôr ḥamets)

The search is then usually conducted by the head of the household joined by his family including children under the supervision of their parents.

It is customary to turn off the lights and conduct the search by candlelight, using a feather and a wooden spoon: candlelight effectively illuminates corners without casting shadows; the feather can dust crumbs out of their hiding places; and the wooden spoon which collects the crumbs can be burned the next day with the chametz. However, most contemporary Jewish-Orthodox authorities permit using a flashlight, while some strongly encourage it due to the danger coupled with using a candle.

Because the house is assumed to have been thoroughly cleaned by the night before Passover, there is some concern that making a blessing over the search for chametz will be in vain (bracha l'vatala) if nothing is found. Thus, 10 morsels of bread or cereal smaller than the size of an olive are traditionally hidden throughout the house in order to ensure that some chametz will be found.

Upon conclusion of the search, with all the small pieces safely wrapped up and put in one bag or place, to be burned the next morning, the following is said:

- Any chametz or leaven that is in my possession which I have not seen and have not removed and do not know about should be annulled and become ownerless like the dust of the earth.

Original declaration as recited in Aramaic:[76]

כל חמירא וחמיעא דאכא ברשותי דלא חמתה ודלא בערתה ודלא ידענא לה לבטל ולהוי הפקר כעפרא דארעא

Morning of 14th of Nisan

Note that if the 14th of Nisan is Shabbat, many of the below will be celebrated on the 13th instead due to restrictions in place during Shabbat.

Fast of the Firstborn

On the day preceding the first Passover seder (or on Thursday morning preceding the seder, when the first seder falls on Motza'ei Shabbat), firstborn sons are commanded to celebrate the Fast of the Firstborn which commemorates the salvation of the Hebrew firstborns. According to Exodus 12:29, God struck down all Egyptian firstborns while the Israelites were not affected.[77] However, it is customary for synagogues to conduct a siyum (ceremony marking the completion of a section of Torah learning) right after morning prayers, and the celebratory meal that follows cancels the firstborn's obligation to fast.

Burning and nullification of leaven

On the morning of the 14th of Nisan, any leavened products that remain in the householder's possession, along with the 10 morsels of bread from the previous night's search, are burned (s'rayfat chametz). The head of the household repeats the declaration of biyur chametz, declaring any chametz that may not have been found to be null and void "as the dust of the earth":

- Any chametz or leaven that is in my possession which I have not seen and have not removed and do not know about should be annulled and become ownerless like the dust of the earth.

Original declaration as recited in Aramaic:[76]

כל חמירא וחמיעא דאכא ברשותי דלא חמתה ודלא בערתה ודלא ידענא לה לבטל ולהוי הפקר כעפרא דארעא

Should more chametz actually be found in the house during the Passover holiday, it must be burnt as soon as possible.

Unlike chametz, which can be eaten any day of the year except during Passover, kosher for Passover foods can be eaten year-round. They need not be burnt or otherwise discarded after the holiday ends.

The historic "Paschal lamb" Passover sacrifice (Korban Pesach) has not been brought following the Romans' destruction of the Second Jewish temple approximately two thousand years ago, and it is therefore still not part of the modern Jewish holiday.

In the times when the Jewish Temples stood, the lamb was slaughtered and cooked on the evening of Passover and was completely consumed before the morning as described in Exodus 12:3–11.[78]

Separate kosher for Passover utensils and dishes

.jpg.webp)

Due to the Torah injunction not to eat chametz (leaven) during Passover,[65] observant families typically own complete sets of serving dishes, glassware and silverware (and in some cases, even separate dishwashers and sinks) which have never come into contact with chametz, for use only during Passover. Under certain circumstances, some chametz utensils can be immersed in boiling water (hagalat keilim) to purge them of any traces of chametz that may have accumulated during the year. Many Sephardic families thoroughly wash their year-round glassware and then use it for Passover, as the Sephardic position is that glass does not absorb enough traces of food to present a problem. Similarly, ovens may be used for Passover either by setting the self-cleaning function to the highest degree for a certain period of time, or by applying a blow torch to the interior until the oven glows red hot (a process called libun gamur).[79]

Matzah

A symbol of the Passover holiday is matzo, an unleavened flatbread made solely from flour and water which is continually worked from mixing through baking, so that it is not allowed to rise. Matzo may be made by machine or by hand. The Torah contains an instruction to eat matzo, specifically, on the first night of Passover and to eat only unleavened bread (in practice, matzo) during the entire week of Passover.[80] Consequently, the eating of matzo figures prominently in the Passover Seder. There are several explanations for this.

The Torah says that it is because the Hebrews left Egypt with such haste that there was no time to allow baked bread to rise; thus flat, unleavened bread, matzo, is a reminder of the rapid departure of the Exodus.[81] Other scholars teach that in the time of the Exodus, matzo was commonly baked for the purpose of traveling because it preserved well and was light to carry (making it similar to hardtack), suggesting that matzo was baked intentionally for the long journey ahead.

Matzo has also been called Lechem Oni (Hebrew: "bread of poverty"). There is an attendant explanation that matzo serves as a symbol to remind Jews what it is like to be a poor slave and to promote humility, appreciate freedom, and avoid the inflated ego symbolized by more luxurious leavened bread.[82]

Shmura matzo ("watched" or "guarded" matzo), is the bread of preference for the Passover Seder in Orthodox Jewish communities. Shmura matzo is made from wheat that is guarded from contamination by leaven (chametz) from the time of summer harvest[62] to its baking into matzos five to ten months later.

In the weeks before Passover, matzos are prepared for holiday consumption. In many Orthodox Jewish communities, men traditionally gather in groups ("chaburas") to bake handmade matzo for use at the Seder, the dough being rolled by hand, resulting in a large and round matzo. Chaburas also work together in machine-made matzo factories, which produce the typically square-shaped matzo sold in stores.

The baking of matzo is labor-intensive,[62] as less than 18 minutes is permitted between the mixing of flour and water to the conclusion of baking and removal from the oven. Consequently, only a small number of matzos can be baked at one time, and the chabura members are enjoined to work the dough constantly so that it is not allowed to ferment and rise. A special cutting tool is run over the dough just before baking to prick any bubbles which might make the matza puff up;[83] this creates the familiar dotted holes in the matzo.

After the matzos come out of the oven, the entire work area is scrubbed down and swept to make sure that no pieces of old, potentially leavened dough remain, as any stray pieces are now chametz, and can contaminate the next batch of matzo.

Some machine-made matzos are completed within 5 minutes of being kneaded.[62]

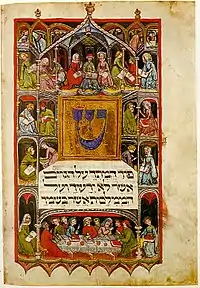

Passover seder

It is traditional for Jewish families to gather on the first night of Passover (first two nights in Orthodox and Conservative communities outside Israel) for a special dinner called a seder (Hebrew: סדר seder – derived from the Hebrew word for "order" or "arrangement", referring to the very specific order of the ritual). The table is set with the finest china and silverware to reflect the importance of the meal. During this meal, the story of the Exodus from Egypt is retold using a special text called the Haggadah. A total of four cups of wine are consumed during the recitation of the Haggadah. The seder is divided by the haggadah into the following 15 parts:

- Kadeish/ Qadēsh קדש – recital of Kiddush blessing and drinking of the first cup of wine

- Urchatz/ Ūr·ḥats/ Ūr·ḥaṣ ורחץ – the washing of the hands – without blessing

- Karpas כרפס – dipping of the karpas in salt water

- Yachatz/ Yaḥats/ Yaḥaṣ יחץ – breaking the middle matzo; the larger piece becomes the afikoman which is eaten later during the ritual of Tzafun

- Maggid/ Maggiyd מגיד – retelling the Passover story, including the recital of "the four questions" and drinking of the second cup of wine

- Rachtzah/ Raḥ·tsah/ Raḥ·ṣah רחצה – second washing of the hands – with blessing

- Motzi/ Môtsiy’/ Môṣiy’ מוציא – traditional blessing before eating bread products

- Matzo/ Maṣo מצה – blessing before eating matzo

- Maror מרור – eating of the maror

- Koreich/ Korēkh כורך – eating of a sandwich made of matzo and maror

- Shulchan oreich/ Shūl·ḥan ‘ôrēkh שולחן עורך – lit. "set table" – the serving of the holiday meal

- Tzafun/ Tsafūn/ Ṣafūn צפון – eating of the afikoman

- Bareich/ Barēkh ברך – blessing after the meal and drinking of the third cup of wine

- Hallel הלל – recital of the Hallel, traditionally recited on festivals; drinking of the fourth cup of wine

- Nirtzah/ Niyr·tsah/ Niyr·ṣah נירצה – conclusion

These 15 parts parallel the 15 steps in the Temple in Jerusalem on which the Levites stood during Temple services, and which were memorialized in the 15 Psalms (#120–134) known as Shir HaMa'a lot (Hebrew: שיר המעלות shiyr ha-ma‘alôth, "Songs of Ascent").[84]

The seder is replete with questions, answers, and unusual practices (e.g. the recital of Kiddush which is not immediately followed by the blessing over bread, which is the traditional procedure for all other holiday meals) to arouse the interest and curiosity of the children at the table. The children are also rewarded with nuts and candies when they ask questions and participate in the discussion of the Exodus and its aftermath. Likewise, they are encouraged to search for the afikoman, the piece of matzo which is the last thing eaten at the seder. Audience participation and interaction is the rule, and many families' seders last long into the night with animated discussions and singing. The seder concludes with additional songs of praise and faith printed in the Haggadah, including Chad Gadya ("One Little Kid" or "One Little Goat").

Maror

Maror (bitter herbs) symbolizes the bitterness of slavery in Egypt. The following verse from the Torah underscores that symbolism: "And they embittered (Hebrew: וימררו ve-yimareru) their lives with hard labor, with mortar and with bricks and with all manner of labor in the field; any labor that they made them do was with hard labor" (Exodus 1:14).

Four cups of wine

There is a Rabbinic requirement that four cups of wine are to be drunk during the seder meal. This applies to both men and women. The Mishnah says (Pes. 10:1) that even the poorest man in Israel has an obligation to drink. Each cup is connected to a different part of the seder: the first cup is for Kiddush, the second cup is connected with the recounting of the Exodus, the drinking of the third cup concludes Birkat Hamazon and the fourth cup is associated with Hallel. A fifth cup of wine is poured near the end of the seder for Eliyahu HaNavi, a symbol of the future redemption, which is left un-touched.[85]

The four questions and participation of children

Children have a very important role in the Passover seder. Traditionally the youngest child is prompted to ask questions about the Passover seder, beginning with the words, Mah Nishtana HaLeila HaZeh (Why is this night different from all other nights?). The questions encourage the gathering to discuss the significance of the symbols in the meal. The questions asked by the child are:

- Why is this night different from all other nights?

- On all other nights, we eat either unleavened or leavened bread, but tonight we eat only unleavened bread?

- On all other nights, we eat all kinds of vegetables, but tonight, we eat only bitter herbs?

- On all other nights, we do not dip [our food] even once, but tonight we dip twice?

- On all other nights, we eat either sitting or reclining, but tonight we only recline?

Often the leader of the seder and the other adults at the meal will use prompted responses from the Haggadah, which states, "The more one talks about the Exodus from Egypt, the more praiseworthy he is." Many readings, prayers, and stories are used to recount the story of the Exodus. Many households add their own commentary and interpretation and often the story of the Jews is related to the theme of liberation and its implications worldwide.

Afikoman

The afikoman – an integral part of the Seder itself – is used to engage the interest and excitement of the children at the table. During the fourth part of the Seder, called Yachatz, the leader breaks the middle piece of matzo into two. He sets aside the larger portion as the afikoman. Many families use the afikoman as a device for keeping the children awake and alert throughout the Seder proceedings by hiding the afikoman and offering a prize for its return.[62] Alternatively, the children are allowed to "steal" the afikoman and demand a reward for its return. In either case, the afikoman must be consumed during the twelfth part of the Seder, Tzafun.

Concluding songs

After the Hallel, the fourth glass of wine is drunk, and participants recite a prayer that ends in "Next year in Jerusalem!". This is followed by several lyric prayers that expound upon God's mercy and kindness, and give thanks for the survival of the Jewish people through a history of exile and hardship. "Echad Mi Yodea" ("Who Knows One?") is a playful song, testing the general knowledge of the children (and the adults). Some of these songs, such as "Chad Gadya" are allegorical.

Counting of the Omer

Beginning on the second night of Passover, the 16th day of Nisan,[86] Jews begin the practice of the Counting of the Omer, a nightly reminder of the approach of the holiday of Shavuot 50 days hence. Each night after the evening prayer service, men and women recite a special blessing and then enumerate the day of the Omer. On the first night, for example, they say, "Today is the first day in (or, to) the Omer"; on the second night, "Today is the second day in the Omer." The counting also involves weeks; thus, the seventh day is commemorated, "Today is the seventh day, which is one week in the Omer." The eighth day is marked, "Today is the eighth day, which is one week and one day in the Omer," etc.[87]

When the Temple stood in Jerusalem, a sheaf of new-cut barley was presented before the altar on the second day of Unleavened Bread. Josephus writes:

On the second day of unleavened bread, that is to say the sixteenth, our people partake of the crops which they have reaped and which have not been touched till then, and esteeming it right first to do homage to God, to whom they owe the abundance of these gifts, they offer to him the first-fruits of the barley in the following way. After parching and crushing the little sheaf of ears and purifying the barley for grinding, they bring to the altar an assaron for God, and, having flung a handful thereof on the altar, they leave the rest for the use of the priests. Thereafter all are permitted, publicly or individually, to begin harvest.[88]

Since the destruction of the Temple, this offering is brought in word rather than deed.

One explanation for the Counting of the Omer is that it shows the connection between Passover and Shavuot. The physical freedom that the Hebrews achieved at the Exodus from Egypt was only the beginning of a process that climaxed with the spiritual freedom they gained at the giving of the Torah at Mount Sinai. Another explanation is that the newborn nation which emerged after the Exodus needed time to learn their new responsibilities vis-a-vis Torah and mitzvot before accepting God's law. The distinction between the Omer offering – a measure of barley, typically animal fodder – and the Shavuot offering – two loaves of wheat bread, human food – symbolizes the transition process.[89]

Chol HaMoed: The intermediate days of Passover

In Israel, Passover lasts for seven days with the first and last days being major Jewish holidays. In Orthodox and Conservative communities, no work is performed on those days, with most of the rules relating to the observances of Shabbat being applied.[90]

Outside Israel, in Orthodox and Conservative communities, the holiday lasts for eight days with the first two days and last two days being major holidays. In the intermediate days necessary work can be performed. Reform Judaism observes Passover over seven days, with the first and last days being major holidays.

Like the holiday of Sukkot, the intermediary days of Passover are known as Chol HaMoed (festival weekdays) and are imbued with a semi-festive status. It is a time for family outings and picnic lunches of matzo, hardboiled eggs, fruits and vegetables, and Passover treats such as macaroons and homemade candies.[90]

Passover cake recipes call for potato starch or Passover cake flour made from finely granulated matzo instead of regular flour, and a large amount of eggs to achieve fluffiness. Cookie recipes use matzo farfel (broken bits of matzo) or ground nuts as the base. For families with Eastern European backgrounds, borsht, a soup made with beets, is a Passover tradition.[91]

While kosher for Passover packaged goods are available in stores, some families opt to cook everything from scratch during Passover week. In Israel, families that do not kasher their ovens can bake cakes, casseroles, and even meat[92] on the stovetop in a Wonder Pot, an Israeli invention consisting of three parts: an aluminium pot shaped like a Bundt pan, a hooded cover perforated with venting holes, and a thick, round, metal disc with a center hole which is placed between the Wonder Pot and the flame to disperse heat.[93]

Seventh day of Passover

Shvi'i shel Pesach (שביעי של פסח) ("seventh [day] of Passover") is another full Jewish holiday, with special prayer services and festive meals. Outside the Land of Israel, in the Jewish diaspora, Shvi'i shel Pesach is celebrated on both the seventh and eighth days of Passover.[94] This holiday commemorates the day the Children of Israel reached the Red Sea and witnessed both the miraculous "Splitting of the Sea" (Passage of the Red Sea), the drowning of all the Egyptian chariots, horses and soldiers that pursued them. According to the Midrash, only the Pharaoh was spared to give testimony to the miracle that occurred.

Hasidic Rebbes traditionally hold a tish on the night of Shvi'i shel Pesach and place a cup or bowl of water on the table before them. They use this opportunity to speak about the Splitting of the Sea to their disciples, and sing songs of praise to God.[95]

Second Passover

The "Second Passover" (Pesach Sheni) on the 14th of Iyar in the Hebrew calendar is mentioned in the Hebrew Bible's Book of Numbers[96] as a make-up day for people who were unable to offer the pesach sacrifice at the appropriate time due to ritual impurity or distance from Jerusalem. Just as on the first Pesach night, breaking bones from the second Paschal offering or leaving meat over until morning is prohibited.[97][98]

Today, Pesach Sheni on the 14th of Iyar has the status of a very minor holiday (so much so that many of the Jewish people have never even heard of it, and it essentially does not exist outside of Orthodox and traditional Conservative Judaism). There are not really any special prayers or observances that are considered Jewish law. The only change in the liturgy is that in some communities Tachanun, a penitential prayer omitted on holidays, is not said. There is a custom, though not Jewish law, to eat just one piece of matzo on that night.[99]

Traditional foods

Because the house is free of leaven (chametz) for eight days, the Jewish household typically eats different foods during the week of Passover. Some include:

Ashkenazi foods

- Matzah brei – Matzo softened in milk or water and fried with egg and fat; served either savory or sweet

- Matzo kugel – A kugel made with matzo instead of noodles

- Charoset – A sweet mixture of fruit, fresh, dried or both; nuts; spices; honey; and sometimes wine. The charoset is a symbol of the mortar the Israelites used for building while enslaved in Egypt (See Passover seder)

- Chrain – Horseradish and beet relish

- Gefilte fish – Poached fish patties or fish balls made from a mixture of ground, de-boned fish, mostly carp or pike

- Chicken soup with matzah balls (kneydlach) – Chicken soup served with matzo-meal dumplings

- Passover noodles – Noodles prepared from potato flour and eggs, served in soup. Batter is fried like thin crepes, which are stacked, rolled up and sliced into ribbons.[100]

Sephardi foods

- Kafteikas di prasa – Fried balls made of leeks, meat, and matzo meal

- Lamb or chicken leg – A symbol of God's strong hand, and korban pesach

- Mina (pastel di pesach) – a meat pie made with matzos

- Spring green vegetables – artichoke, fava beans, peas

Sermons, liturgy, and song

The story of Passover, with its message that slaves can go free, and that the future can be better than the present, has inspired a number of religious sermons, prayers, and songs – including spirituals (what used to be called "Negro Spirituals"), within the African-American community.

Rabbi Philip R. Alstat, an early leader of Conservative Judaism, known for his fiery rhetoric and powerful oratory skills, wrote and spoke in 1939 about the power of the Passover story during the rise of Nazi persecution and terror:[101]

Perhaps in our generation the counsel of our Talmudic sages may seem superfluous, for today the story of our enslavement in Egypt is kept alive not only by ritualistic symbolism, but even more so by tragic realism. We are the contemporaries and witnesses of its daily re-enactment. Are not our hapless brethren in the German Reich eating "the bread of affliction"? Are not their lives embittered by complete disenfranchisement and forced labor? Are they not lashed mercilessly by brutal taskmasters behind the walls of concentration camps? Are not many of their men-folk being murdered in cold blood? Is not the ruthlessness of the Egyptian Pharaoh surpassed by the sadism of the Nazi dictators?

And yet, even in this hour of disaster and degradation, it is still helpful to "visualize oneself among those who had gone forth out of Egypt." It gives stability and equilibrium to the spirit. Only our estranged kinsmen, the assimilated, and the de-Judaized, go to pieces under the impact of the blow....But those who visualize themselves among the groups who have gone forth from the successive Egypts in our history never lose their sense of perspective, nor are they overwhelmed by confusion and despair.... It is this faith, born of racial experience and wisdom, which gives the oppressed the strength to outlive the oppressors and to endure until the day of ultimate triumph when we shall "be brought forth from bondage unto freedom, from sorrow unto joy, from mourning unto festivity, from darkness unto great light, and from servitude unto redemption.

Related celebrations in other religions

Saint Thomas Syrian Christians observe Maundy Thursday as Pesaha, a Malayalam word derived from the Aramaic or Hebrew word for Passover (Pasha, Pesach or Pesah), commemorating the Korban Pesach and Last Supper of Jesus Christ during Passover in Jerusalem. The tradition of consuming Pesaha Appam after the church service is observed by the entire community under the leadership of the head of the family. Special long services followed by the Holy Qurbana are conducted during the Pesaha eve in the churches. The tradition of Pesaha was established among the Saint Thomas Syrian Christian community by the Jewish Knanaya community, an endogamous subgroup among the Saint Thomas Syrian Christians.[102][103]

The Samaritan religion celebrates its own, similar Passover holiday, based on the Samaritan Pentateuch. Samaritanism holds that the Jews and Samaritans share a common history, but split into distinct communities after the time of Moses.[104] Passover is also celebrated in Karaite Judaism,[105] which rejects the Oral Torah that characterizes mainstream Rabbinic Judaism, as well as other groups claiming affiliation with Israelites.[106]

In Christianity, the celebration of Easter (not to be confused with the pre-Christian Saxon festival from which it derives its English name) and its date in the calendar finds its roots in the Jewish feast of Passover, when, according to Christian interpretation, Jesus was crucified as the Passover Lamb.[107][108][109] The coincidence of Jesus' crucifixion with the Jewish Passover led some early Christians to make a false etymological association between Hebrew Pesach and Greek pascho ("suffer").[110]

Quartodeciman Christians continued to end the Lenten fast in time to observe Passover as a Christian holiday, which occurs before the Lord's day, as the two are not mutually exclusive. However due to intense persecution from Nicene Christianity after the Easter controversy, the practice had mostly died out by the 5th or 6th century, and only re-emerged in the 20th century.[111]

Some Christians, including Messianic Jews, also celebrate Passover itself as a Christian holiday.[112]

See also

- The Exodus Decoded

- Gebrochts

- Jewish greetings

- Kitniyot

- Quartodecimanism

References

- "Dates for Passover". Hebcal.com by Danny Sadinoff and Michael J. Radwin (CC-BY-3.0). Retrieved August 26, 2018.

- "Pesach" Archived November 30, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary

- "What is Passover? – Learn All About the Passover Holiday". Tori Avey. March 4, 2012. Archived from the original on October 18, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- "Pesach and Chag HaMatzot – A Two for One?". AlHaTorah.org. Retrieved April 11, 2022.

- Exodus 12:27

- "Exodus 13:8". Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- Exodus 12:23

- "Exodus 12:23". www.sefaria.org. Archived from the original on August 6, 2020. Retrieved April 9, 2019.

- Prosic, p. 32.

- Exodus 12:3

- "King James Bible Borrowed From Earlier Translation". NPR.org. Archived from the original on August 6, 2020. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- Gilad, Elon (April 1, 2015). "The Enigmatic Origins of the Words of the Passover Seder". Haaretz. Archived from the original on April 22, 2020. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- Exodus 12:23 (King James Version 1611)

- Audirsch, Jeffrey G. (2014). The Legislative Themes of Centralization: From Mandate to Demise. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 108. ISBN 978-1620320389. Archived from the original on April 3, 2017. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- Levinson, Bernard M. (1997). Deuteronomy and the Hermeneutics of Legal Innovation. Oxford University Press. pp. 57–58. ISBN 978-0195354577. Archived from the original on April 3, 2017. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- Prosic, Tamara (2004). The Development and Symbolism of Passover. A&C Black. pp. 23–27. ISBN 978-0567287892. Archived from the original on April 3, 2017. Retrieved April 23, 2016.

- Prosic, p. 28

- Prosic pp. 28ff. pp. 32ff.

- Exodus 13:7

- Exodus 12:6

- Exodus 12:6 English Standard Version

- Exodus 12:8

- Exodus 12:9

- Exodus 12:10

- Exodus 12:11

- Deuteronomy 16:2–6

- Deuteronomy 16:2, 5

- Exodus 12:14

- Exodus 13:3

- Deuteronomy 16:12

- 2 Kings 23:21–23 and 2 Chronicles 35:1–19

- 2 Kings 23:21–23; 2 Chronicles 35:1–18

- Ezra 6:19–21

- James B. Prichard, ed., The Ancient Near East – An Anthology of Texts and Pictures, Volume 1, Princeton University Press, 1958, p. 278.

- "On the feast called Passover...they sacrifice from the ninth to the eleventh hour", Josephus, Jewish War 6.423–428, in Josephus III, The Jewish War, Book IV–VII, Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1979. Philo in one place (Special Laws 2.148) states that the victims are sacrificed "from noon till eventide", and in another place (Questions on Exodus 1.11) that the sacrifices begin at the ninth hour. According to Jubilees 49.12, "it is not fitting to sacrifice [the Passover] during any time of light except during the time of the border of evening."

- Jubilees 49.1.

- "And what is left of its flesh from the third of the night and beyond, they shall burn with fire," Jubilees 49.12. "We celebrate [the Passover] by fraternities, nothing of the sacrificial victims being kept for the morrow," Josephus, Antiquities 3.248.

- "The guests assembled for the banquet have been cleansed by purificatory lustrations, and are there...to fulfill with prayers and hymns the custom handed down by their fathers." Philo, Special Laws 2.148, in Philo VII: On the Decalog; On the Special Laws I–III, Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1937.

- Hopkins, Edward J. (1996). "Full Moon, Easter & Passover". University of Wisconsin. Archived from the original on June 7, 2018. Retrieved April 10, 2017.

- The barley had to be "eared out" (ripe) in order to have a wave-sheaf offering of the first fruits according to the Law. Jones, Stephen (1996). Secrets of Time. This also presupposes that the cycle is based on the northern hemisphere seasons.

- "..., when the fruit had not grown properly, when the winter rains had not stopped, when the roads for Passover pilgrims had not dried up, and when the young pigeons had not become fledged. The council on intercalation considered the astronomical facts together with the religious requirements of Passover and the natural conditions of the country." – Spier, Arthur (1952). The Comprehensive Hebrew Calendar. New York: Behrman House, Inc., p. 1

- "In the fourth century, ... the patriarch Hillel II ... made public the system of calendar calculation which up to then had been a closely guarded secret. It had been used in the past only to check the observations and testimonies of witnesses, and to determine the beginning of the spring season." – Spier 1952, p. 2

- Shapiro, Mark Dov. "How Long is Passover?". sinai-temple.org. Sinai Temple. Archived from the original on April 7, 2015. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- Dreyfus, Ben. "Is Passover 7 or 8 Days?". ReformJudaism.org. Union for Reform Judaism. Archived from the original on April 8, 2015. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- "What Is Passover?". Rabbinical College of Australia and N.Z. Archived from the original on August 5, 2012. Retrieved March 17, 2012.

- Stern, Sacha (2001). Calendar and Community: A History of the Jewish Calendar 2nd Century BCE – 10th Century CE. Oxford University Press. p. viii. ISBN 0198270348.

- Reinhold Pummer,The Samaritans, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2016 ISBN 978-0-802-86768-1pp.7,258ff.

- Cohen, Jeffrey M. (2008). 1,001 Questions and Answers on Pesach. p. 291. ISBN 978-0853038085.

- Bokser, Baruch M. (1992) "Unleavened Bread and Passover, Feasts of" in The Anchor Bible Dictionary, ed. David Noel Freedman (New York: Doubleday), 6:755–765

- Numbers 9:11

- Exodus 12:6

- Exodus 23:18

- Exodus 12:9

- Exodus 12:46

- Exodus 12:10 Exodus 23:18

- Exodus 12:43

- Exodus 12:45

- Exodus 12:48

- Pesahim 66b

- Pesahim 64b

- Kitov, Eliyahu (1997). The Book of Our Heritage: The Jewish Year and Its Days of Significance. Feldheim. p. 562.

- Pomerantz, Batsheva (April 22, 2005). "Making matzo: A time-honored tradition". Jewish News of Greater Phoenix. Archived from the original on January 14, 2013.

- "Which Foods are Chametz?". Kosher for Passover. January 23, 2013. Archived from the original on April 7, 2020. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- "What Is Chametz (Chometz)?". www.chabad.org. Archived from the original on April 11, 2020. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- Exodus 12:15

- Exodus 13:3, Exodus 12:20, Deuteronomy 16:3

- Exodus 12:19, Deuteronomy 16:4

- "Ultra Orthodox burn leavened food before Passover". Haaretz. April 19, 2011. Archived from the original on April 19, 2014. Retrieved April 17, 2014.

- Rotkovitz, Miri (May 6, 2016). "Get Out of Town: Your Guide to Kosher Travel". The Spruce. Archived from the original on April 10, 2017. Retrieved April 10, 2017.

- Greenberg, Moshe (1974) "Lessons on Exodus". New York

- Sarna, Nahum M. (1986) "Exploring Exodus". New York

- "The Laws Concerning the Thirty Days before Passover". www.chabad.org. Archived from the original on August 6, 2020. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- Cohen, Rabbi J. Simcha. "Eating Matzah Before Pesach". Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- Jacobs, Louis; Rose, Michael (March 23, 1983). "The Laws of Pesach". Friends of Louis Jacobs. Archived from the original on April 10, 2017. Retrieved April 10, 2017.

- Pesach questions and answers Archived September 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine by the Torah Learning Center. Retrieved on March 31, 2018

- Gold, Avie; Zlotowitz, Meir; Scherman, Nosson (1990–2002). The Complete ArtScroll Machzor: Pesach. Brooklyn, New York: Mesorah Publications, Ltd. pp. 2–3. ISBN 0-89906-696-8.

- Exodus 12:29

- Exodus 12:3–11

- Lagnado, Lucette (April 18, 2011). "As Passover Nears, These Rabbis Are Getting Out Their Blowtorches". The Wall Street Journal. New York. p. A1. Archived from the original on August 25, 2017. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- Exodus 12:18

- "Thought For Food: An Overview of the Seder". AskMoses.com – Judaism, Ask a Rabbi – Live. Archived from the original on May 21, 2020. Retrieved September 29, 2006.

- What is the kabbalistic view on chametz? Archived February 3, 2008, at the Wayback Machine by Rabbi Yossi Marcus

- "Making Matzah the Old-Fashioned Way". The Jewish Federations of North America. Archived from the original on April 2, 2012. Retrieved April 17, 2014.

- "Shir Ha Ma'a lot". Kolhator.org.il. Archived from the original on March 15, 2012. Retrieved April 17, 2014.

- "Elijah's cup". Britannica. Retrieved April 11, 2022.

- Karaite Jews begin the count on the Sunday within the holiday week. This leads to Shavuot for the Karaites always falling on a Sunday.

- Scharfstein, Sol (1999). Understanding Jewish Holidays and Customs: Historical and Contemporary. pp. 36–37. ISBN 0881256269.

- Josephus, Antiquities 3.250–251, in Josephus IV Jewish Antiquities Books I–IV, Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1930, pp. 437–439.

- Cohn, Ellen (2000). "In Search of the Omer". In Bernstein, Ellen (ed.). Ecology and the Jewish Spirit: Where Nature and the Sacred Meet. p. 164. ISBN 1580230822. Archived from the original on April 10, 2017. Retrieved April 10, 2017.

- "Chol Hamoed - the "Intermediate" Festival Days - Sukkot & Simchat Torah". Archived from the original on April 6, 2020. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- "The Perfect Borscht". The Forward. January 5, 2011. Archived from the original on April 6, 2020. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

- "Roast in the Wonder Pot", The Kosher For Pesach Cookbook (1978). Jerusalem: Yeshivat Aish HaTorah Women's Organization, p. 58.

- Neiman, Rachel (June 15, 2008). "Nostalgia Sunday". 21c Israelity blog. Archived from the original on April 27, 2011. Retrieved April 1, 2010.

- The eighth day is known as Acharon shel Pesach, "last [day] of Passover".

- "The Eve of Shvi'i shel Pesach". Chabad.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Numbers 9:6–13

- Numbers 9:12

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 6, 2020. Retrieved April 16, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "YomTov, Vol. I, # 21 – Pesach Sheni, The "Second" Pesach". Torah.org. March 2016. Archived from the original on August 6, 2020. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- "Grandma Hanna's Lokshen Are a Perfect Passover Dish". Haaretz. April 6, 2017. Archived from the original on February 20, 2019. Retrieved April 9, 2019.

- The Canadian Jewish Chronicle, March 31, 1939

- "NSC Network – Passover". Nasrani.net. March 25, 2007. Archived from the original on June 8, 2012. Retrieved June 16, 2012.

- Weil, S. (1982)"Symmetry between Christians and Jews in India: The Cananite Christians and Cochin Jews in Kerala". in Contributions to Indian Sociology, 16.

- "The very ancient Passover of one of the smallest religions in the world". Culture. April 19, 2019. Archived from the original on July 12, 2019. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- Kramer, Faith (March 30, 2012). "Karaites celebrate Passover strictly from Torah". J. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- "KARAITES AND KARAISM - JewishEncyclopedia.com". www.jewishencyclopedia.com. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- Leonhard, Clemens (2012). The Jewish Pesach and the Origins of the Christian Easter. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3110927818. Archived from the original on February 17, 2022. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- Karl Gerlach (1998). The Antenicene Pascha: A Rhetorical History. Peeters Publishers. p. 21. ISBN 978-9042905702. Archived from the original on December 28, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

Long before this controversy, Ex 12 as a story of origins and its ritual expression had been firmly fixed in the Christian imagination. Though before the final decades of the second century only accessible as an exegetical tradition, already in the Paulin letters the Exodus saga is deeply involved with the celebration of bath and meal. Even here, this relationship does not suddenly appear, but represents developments in ritual narrative that must have begun at the very inception of the Christian message. Jesus of Nazareth was crucifed during Pesach-Mazzot, an event that a new covenant people of Jews and Gentiles both saw as definitive and defining. Ex 12 is thus one of the few reliable guides for tracing the synergism among ritual, text, and kerygma before the Council of Nicaea.

- Matthias Reinhard Hoffmann (2005). The Destroyer and the Lamb: The Relationship Between Angelomorphic and Lamb Christology in the Book of Revelation. Mohr Siebeck. p. 117. ISBN 3-16-148778-8. Archived from the original on January 8, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

1.2.2. Christ as the Passover Lamb from Exodus A number of features throughout Revelation seem to correspond to Exodus 12: The connection of Lamb and Passover, a salvific effect of the Lamb's blood and the punishment of God's (and His people's) opponents from Exodus 12 may possibly be reflected within the settings of the Apocalypse. The concept of Christ as a Passover lamb is generally not unknown in NT or early Christian literature, as can for instance be seen in 1 Corinthians 5:7, 1 Peter 1:19 or Justin Martyr's writing (Dial. 111:3). In the Gospel of John, especially, this connection between Christ and Passover is made very explicit.

- Reece, Steve, “Passover as ‘Passion’: A Folk Etymology in Luke 22:15,” Biblica (Peeters Publishers, Leuven, Belgium) 100 (2019) 601–610.

- "The Meaning of Passover | Chosen People Ministries". July 8, 2011. Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- "God's Holy Day Plan > United Church of God". June 19, 2010. Archived from the original on June 19, 2010. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

External links

- Passover Resources – ReformJudaism.org

- Guide to Passover – chabad.org

- 'Peninei Halakha' Jewish Law – Yhb.org.il

- Aish.com Passover Primer

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Passover

- Akhlah: The Jewish Children's Learning Network

- All about Pesach

- Secular dates for passover

- Passover collected news and commentary at The New York Times