English language

English is a West Germanic language of the Indo-European language family, with its earliest forms spoken by the inhabitants of early medieval England.[3][4][5] It is named after the Angles, one of the ancient Germanic peoples that migrated to the island of Great Britain. English is genealogically West Germanic, closest related to the Low Saxon and Frisian languages; however, its vocabulary is also distinctively influenced by dialects of French (about 29% of modern English words) and Latin (also about 29%), plus some grammar and a small amount of core vocabulary influenced by Old Norse (a North Germanic language).[6][7][8] Speakers of English are called Anglophones.

| English | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈɪŋɡlɪʃ/[1] |

| Ethnicity | English people (see also Anglophones) |

Native speakers | 360–400 million (2006)[2] L2 speakers: 750 million; as a foreign language: 600–700 million[2] |

Indo-European

| |

Early forms | Old English

|

| |

Signed forms | Manually coded English (multiple systems) |

| Official status | |

Official language in |

Various organisations

|

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | en |

| ISO 639-2 | eng |

| ISO 639-3 | eng |

| Glottolog | stan1293 |

| Linguasphere | 52-ABA |

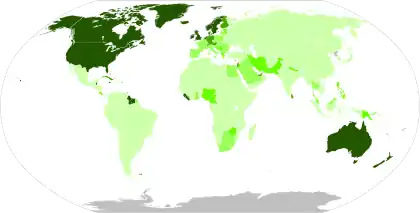

Regions where English is a majority native language

Regions where English is official or widely spoken, but not as a primary native language | |

| Part of a series on the |

| English language |

|---|

| Topics |

|

| Advanced topics |

|

| Phonology |

|

| Dialects |

|

| Teaching |

Higher category: Language |

The earliest forms of English, collectively known as Old English, evolved from a group of West Germanic (Ingvaeonic) dialects brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers in the 5th century and further mutated by Norse-speaking Viking settlers starting in the 8th and 9th centuries. Middle English began in the late 11th century after the Norman conquest of England, when considerable French (especially Old Norman) and Latin-derived vocabulary was incorporated into English over some three hundred years.[9][10] Early Modern English began in the late 15th century with the start of the Great Vowel Shift and the Renaissance trend of borrowing further Latin and Greek words and roots into English, concurrent with the introduction of the printing press to London. This era notably culminated in the King James Bible and plays of William Shakespeare.[11][12]

Modern English grammar is the result of a gradual change from a typical Indo-European dependent-marking pattern, with a rich inflectional morphology and relatively free word order, to a mostly analytic pattern with little inflection, and a fairly fixed subject–verb–object word order.[13] Modern English relies more on auxiliary verbs and word order for the expression of complex tenses, aspect and mood, as well as passive constructions, interrogatives and some negation.

Modern English has spread around the world since the 17th century as a consequence of the worldwide influence of the British Empire and the United States of America. Through all types of printed and electronic media of these countries, English has become the leading language of international discourse and the lingua franca in many regions and professional contexts such as science, navigation and law.[3] English is the most spoken language in the world[14] and the third-most spoken native language in the world, after Standard Chinese and Spanish.[15] It is the most widely learned second language and is either the official language or one of the official languages in 59 sovereign states. There are more people who have learned English as a second language than there are native speakers. As of 2005, it was estimated that there were over 2 billion speakers of English.[16] English is the majority native language in the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand. and the Republic of Ireland (see Anglosphere), and is widely spoken in some areas of the Caribbean, Africa, South Asia, Southeast Asia, and Oceania.[17] It is a co-official language of the United Nations, the European Union and many other world and regional international organisations. It is the most widely spoken Germanic language, accounting for at least 70% of speakers of this Indo-European branch.

Classification

Anglic and North Sea Germanic languages Anglo-Frisian and West Germanic languages

North Sea Germanic and ...... German (High):

English is an Indo-European language and belongs to the West Germanic group of the Germanic languages.[18] Old English originated from a Germanic tribal and linguistic continuum along the Frisian North Sea coast, whose languages gradually evolved into the Anglic languages in the British Isles, and into the Frisian languages and Low German/Low Saxon on the continent. The Frisian languages, which together with the Anglic languages form the Anglo-Frisian languages, are the closest living relatives of English. Low German/Low Saxon is also closely related, and sometimes English, the Frisian languages, and Low German are grouped together as the Ingvaeonic (North Sea Germanic) languages, though this grouping remains debated.[7] Old English evolved into Middle English, which in turn evolved into Modern English.[19] Particular dialects of Old and Middle English also developed into a number of other Anglic languages, including Scots[20] and the extinct Fingallian and Forth and Bargy (Yola) dialects of Ireland.[21]

Like Icelandic and Faroese, the development of English in the British Isles isolated it from the continental Germanic languages and influences, and it has since diverged considerably. English is not mutually intelligible with any continental Germanic language, differing in vocabulary, syntax, and phonology, although some of these, such as Dutch or Frisian, do show strong affinities with English, especially with its earlier stages.[22]

Unlike Icelandic and Faroese, which were isolated, the development of English was influenced by a long series of invasions of the British Isles by other peoples and languages, particularly Old Norse and Norman French. These left a profound mark of their own on the language, so that English shows some similarities in vocabulary and grammar with many languages outside its linguistic clades—but it is not mutually intelligible with any of those languages either. Some scholars have argued that English can be considered a mixed language or a creole—a theory called the Middle English creole hypothesis. Although the great influence of these languages on the vocabulary and grammar of Modern English is widely acknowledged, most specialists in language contact do not consider English to be a true mixed language.[23][24]

English is classified as a Germanic language because it shares innovations with other Germanic languages such as Dutch, German, and Swedish.[25] These shared innovations show that the languages have descended from a single common ancestor called Proto-Germanic. Some shared features of Germanic languages include the division of verbs into strong and weak classes, the use of modal verbs, and the sound changes affecting Proto-Indo-European consonants, known as Grimm's and Verner's laws. English is classified as an Anglo-Frisian language because Frisian and English share other features, such as the palatalisation of consonants that were velar consonants in Proto-Germanic (see Phonological history of Old English § Palatalization).[26]

History

Proto-Germanic to Old English

Hƿæt ƿē Gārde/na ingēar dagum þēod cyninga / þrym ge frunon...

"Listen! We of the Spear-Danes from days of yore have heard of the glory of the folk-kings..."

The earliest form of English is called Old English or Anglo-Saxon (c. year 550–1066). Old English developed from a set of West Germanic dialects, often grouped as Anglo-Frisian or North Sea Germanic, and originally spoken along the coasts of Frisia, Lower Saxony and southern Jutland by Germanic peoples known to the historical record as the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes.[27][28] From the 5th century, the Anglo-Saxons settled Britain as the Roman economy and administration collapsed. By the 7th century, the Germanic language of the Anglo-Saxons became dominant in Britain, replacing the languages of Roman Britain (43–409): Common Brittonic, a Celtic language, and Latin, brought to Britain by the Roman occupation.[29][30][31] England and English (originally Ænglaland and Ænglisc) are named after the Angles.[32]

Old English was divided into four dialects: the Anglian dialects (Mercian and Northumbrian) and the Saxon dialects, Kentish and West Saxon.[33] Through the educational reforms of King Alfred in the 9th century and the influence of the kingdom of Wessex, the West Saxon dialect became the standard written variety.[34] The epic poem Beowulf is written in West Saxon, and the earliest English poem, Cædmon's Hymn, is written in Northumbrian.[35] Modern English developed mainly from Mercian, but the Scots language developed from Northumbrian. A few short inscriptions from the early period of Old English were written using a runic script.[36] By the 6th century, a Latin alphabet was adopted, written with half-uncial letterforms. It included the runic letters wynn ⟨ƿ⟩ and thorn ⟨þ⟩, and the modified Latin letters eth ⟨ð⟩, and ash ⟨æ⟩.[36][37]

Old English is essentially a distinct language from Modern English and is virtually impossible for 21st-century unstudied English-speakers to understand. Its grammar was similar to that of modern German, and its closest relative is Old Frisian. Nouns, adjectives, pronouns, and verbs had many more inflectional endings and forms, and word order was much freer than in Modern English. Modern English has case forms in pronouns (he, him, his) and has a few verb inflections (speak, speaks, speaking, spoke, spoken), but Old English had case endings in nouns as well, and verbs had more person and number endings.[38][39][40]

The translation of Matthew 8:20 from 1000 shows examples of case endings (nominative plural, accusative plural, genitive singular) and a verb ending (present plural):

- Foxas habbað holu and heofonan fuglas nest

- Fox-as habb-að hol-u and heofon-an fugl-as nest-∅

- fox-NOM.PL have-PRS.PL hole-ACC.PL and heaven-GEN.SG bird-NOM.PL nest-ACC.PL

- "Foxes have holes and the birds of heaven nests"[41]

Middle English

Englischmen þeyz hy hadde fram þe bygynnyng þre manner speche, Souþeron, Northeron, and Myddel speche in þe myddel of þe lond, ... Noþeles by comyxstion and mellyng, furst wiþ Danes, and afterward wiþ Normans, in menye þe contray longage ys asperyed, and som vseþ strange wlaffyng, chyteryng, harryng, and garryng grisbytting.

Although, from the beginning, Englishmen had three manners of speaking, southern, northern and midlands speech in the middle of the country, ... Nevertheless, through intermingling and mixing, first with Danes and then with Normans, amongst many the country language has arisen, and some use strange stammering, chattering, snarling, and grating gnashing.

John of Trevisa, ca. 1385[42]

From the 8th to the 12th century, Old English gradually transformed through language contact into Middle English. Middle English is often arbitrarily defined as beginning with the conquest of England by William the Conqueror in 1066, but it developed further in the period from 1200 to 1450.

First, the waves of Norse colonisation of northern parts of the British Isles in the 8th and 9th centuries put Old English into intense contact with Old Norse, a North Germanic language. Norse influence was strongest in the north-eastern varieties of Old English spoken in the Danelaw area around York, which was the centre of Norse colonisation; today these features are still particularly present in Scots and Northern English. However the centre of norsified English seems to have been in the Midlands around Lindsey, and after 920 CE when Lindsey was reincorporated into the Anglo-Saxon polity, Norse features spread from there into English varieties that had not been in direct contact with Norse speakers. An element of Norse influence that persists in all English varieties today is the group of pronouns beginning with th- (they, them, their) which replaced the Anglo-Saxon pronouns with h- (hie, him, hera).[43]

With the Norman conquest of England in 1066, the now norsified Old English language was subject to contact with Old French, in particular with the Old Norman dialect. The Norman language in England eventually developed into Anglo-Norman.[9] Because Norman was spoken primarily by the elites and nobles, while the lower classes continued speaking Anglo-Saxon (English), the main influence of Norman was the introduction of a wide range of loanwords related to politics, legislation and prestigious social domains.[8] Middle English also greatly simplified the inflectional system, probably in order to reconcile Old Norse and Old English, which were inflectionally different but morphologically similar. The distinction between nominative and accusative cases was lost except in personal pronouns, the instrumental case was dropped, and the use of the genitive case was limited to indicating possession. The inflectional system regularised many irregular inflectional forms,[44] and gradually simplified the system of agreement, making word order less flexible.[45] In the Wycliffe Bible of the 1380s, the verse Matthew 8:20 was written: Foxis han dennes, and briddis of heuene han nestis[46] Here the plural suffix -n on the verb have is still retained, but none of the case endings on the nouns are present. By the 12th century Middle English was fully developed, integrating both Norse and French features; it continued to be spoken until the transition to early Modern English around 1500. Middle English literature includes Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales, and Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur. In the Middle English period, the use of regional dialects in writing proliferated, and dialect traits were even used for effect by authors such as Chaucer.[47]

Early Modern English

The next period in the history of English was Early Modern English (1500–1700). Early Modern English was characterised by the Great Vowel Shift (1350–1700), inflectional simplification, and linguistic standardisation.

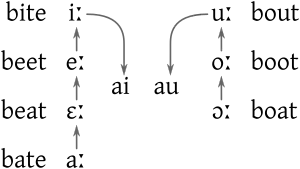

The Great Vowel Shift affected the stressed long vowels of Middle English. It was a chain shift, meaning that each shift triggered a subsequent shift in the vowel system. Mid and open vowels were raised, and close vowels were broken into diphthongs. For example, the word bite was originally pronounced as the word beet is today, and the second vowel in the word about was pronounced as the word boot is today. The Great Vowel Shift explains many irregularities in spelling since English retains many spellings from Middle English, and it also explains why English vowel letters have very different pronunciations from the same letters in other languages.[48][49]

English began to rise in prestige, relative to Norman French, during the reign of Henry V. Around 1430, the Court of Chancery in Westminster began using English in its official documents, and a new standard form of Middle English, known as Chancery Standard, developed from the dialects of London and the East Midlands. In 1476, William Caxton introduced the printing press to England and began publishing the first printed books in London, expanding the influence of this form of English.[50] Literature from the Early Modern period includes the works of William Shakespeare and the translation of the Bible commissioned by King James I. Even after the vowel shift the language still sounded different from Modern English: for example, the consonant clusters /kn ɡn sw/ in knight, gnat, and sword were still pronounced. Many of the grammatical features that a modern reader of Shakespeare might find quaint or archaic represent the distinct characteristics of Early Modern English.[51]

In the 1611 King James Version of the Bible, written in Early Modern English, Matthew 8:20 says, "The Foxes haue holes and the birds of the ayre haue nests."[41] This exemplifies the loss of case and its effects on sentence structure (replacement with subject–verb–object word order, and the use of of instead of the non-possessive genitive), and the introduction of loanwords from French (ayre) and word replacements (bird originally meaning "nestling" had replaced OE fugol).[41]

Spread of Modern English

By the late 18th century, the British Empire had spread English through its colonies and geopolitical dominance. Commerce, science and technology, diplomacy, art, and formal education all contributed to English becoming the first truly global language. English also facilitated worldwide international communication.[52][3] England continued to form new colonies, and these later developed their own norms for speech and writing. English was adopted in parts of North America, parts of Africa, Australasia, and many other regions. When they obtained political independence, some of the newly independent nations that had multiple indigenous languages opted to continue using English as the official language to avoid the political and other difficulties inherent in promoting any one indigenous language above the others.[53][54][55] In the 20th century the growing economic and cultural influence of the United States and its status as a superpower following the Second World War has, along with worldwide broadcasting in English by the BBC[56] and other broadcasters, caused the language to spread across the planet much faster.[57][58] In the 21st century, English is more widely spoken and written than any language has ever been.[59]

As Modern English developed, explicit norms for standard usage were published, and spread through official media such as public education and state-sponsored publications. In 1755 Samuel Johnson published his A Dictionary of the English Language, which introduced standard spellings of words and usage norms. In 1828, Noah Webster published the American Dictionary of the English language to try to establish a norm for speaking and writing American English that was independent of the British standard. Within Britain, non-standard or lower class dialect features were increasingly stigmatised, leading to the quick spread of the prestige varieties among the middle classes.[60]

In modern English, the loss of grammatical case is almost complete (it is now only found in pronouns, such as he and him, she and her, who and whom), and SVO word order is mostly fixed.[60] Some changes, such as the use of do-support, have become universalised. (Earlier English did not use the word "do" as a general auxiliary as Modern English does; at first it was only used in question constructions, and even then was not obligatory.[61] Now, do-support with the verb have is becoming increasingly standardised.) The use of progressive forms in -ing, appears to be spreading to new constructions, and forms such as had been being built are becoming more common. Regularisation of irregular forms also slowly continues (e.g. dreamed instead of dreamt), and analytical alternatives to inflectional forms are becoming more common (e.g. more polite instead of politer). British English is also undergoing change under the influence of American English, fuelled by the strong presence of American English in the media and the prestige associated with the US as a world power.[62][63][64]

Geographical distribution

As of 2016, 400 million people spoke English as their first language, and 1.1 billion spoke it as a secondary language.[65] English is the largest language by number of speakers. English is spoken by communities on every continent and on islands in all the major oceans.[66]

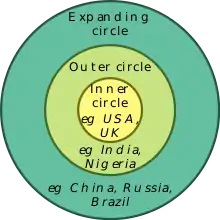

The countries where English is spoken can be grouped into different categories according to how English is used in each country. The "inner circle"[67] countries with many native speakers of English share an international standard of written English and jointly influence speech norms for English around the world. English does not belong to just one country, and it does not belong solely to descendants of English settlers. English is an official language of countries populated by few descendants of native speakers of English. It has also become by far the most important language of international communication when people who share no native language meet anywhere in the world.

Three circles of English-speaking countries

The Indian linguist Braj Kachru distinguished countries where English is spoken with a three circles model.[67] In his model,

- the "inner circle" countries have large communities of native speakers of English,

- "outer circle" countries have small communities of native speakers of English but widespread use of English as a second language in education or broadcasting or for local official purposes, and

- "expanding circle" countries are countries where many people learn English as a foreign language.

Kachru based his model on the history of how English spread in different countries, how users acquire English, and the range of uses English has in each country. The three circles change membership over time.[68]

Countries with large communities of native speakers of English (the inner circle) include Britain, the United States, Australia, Canada, Ireland, and New Zealand, where the majority speaks English, and South Africa, where a significant minority speaks English. The countries with the most native English speakers are, in descending order, the United States (at least 231 million),[69] the United Kingdom (60 million),[70][71][72] Canada (19 million),[73] Australia (at least 17 million),[74] South Africa (4.8 million),[75] Ireland (4.2 million), and New Zealand (3.7 million).[76] In these countries, children of native speakers learn English from their parents, and local people who speak other languages and new immigrants learn English to communicate in their neighbourhoods and workplaces.[77] The inner-circle countries provide the base from which English spreads to other countries in the world.[68]

Estimates of the numbers of second language and foreign-language English speakers vary greatly from 470 million to more than 1 billion, depending on how proficiency is defined.[17] Linguist David Crystal estimates that non-native speakers now outnumber native speakers by a ratio of 3 to 1.[78] In Kachru's three-circles model, the "outer circle" countries are countries such as the Philippines,[79] Jamaica,[80] India, Pakistan, Singapore,[81] Malaysia and Nigeria[82][83] with a much smaller proportion of native speakers of English but much use of English as a second language for education, government, or domestic business, and its routine use for school instruction and official interactions with the government.[84]

Those countries have millions of native speakers of dialect continua ranging from an English-based creole to a more standard version of English. They have many more speakers of English who acquire English as they grow up through day-to-day use and listening to broadcasting, especially if they attend schools where English is the medium of instruction. Varieties of English learned by non-native speakers born to English-speaking parents may be influenced, especially in their grammar, by the other languages spoken by those learners.[77] Most of those varieties of English include words little used by native speakers of English in the inner-circle countries,[77] and they may show grammatical and phonological differences from inner-circle varieties as well. The standard English of the inner-circle countries is often taken as a norm for use of English in the outer-circle countries.[77]

In the three-circles model, countries such as Poland, China, Brazil, Germany, Japan, Indonesia, Egypt, and other countries where English is taught as a foreign language, make up the "expanding circle".[85] The distinctions between English as a first language, as a second language, and as a foreign language are often debatable and may change in particular countries over time.[84] For example, in the Netherlands and some other countries of Europe, knowledge of English as a second language is nearly universal, with over 80 percent of the population able to use it,[86] and thus English is routinely used to communicate with foreigners and often in higher education. In these countries, although English is not used for government business, its widespread use puts them at the boundary between the "outer circle" and "expanding circle". English is unusual among world languages in how many of its users are not native speakers but speakers of English as a second or foreign language.[87]

Many users of English in the expanding circle use it to communicate with other people from the expanding circle, so that interaction with native speakers of English plays no part in their decision to use the language.[88] Non-native varieties of English are widely used for international communication, and speakers of one such variety often encounter features of other varieties.[89] Very often today a conversation in English anywhere in the world may include no native speakers of English at all, even while including speakers from several different countries. This is particularly true of the shared vocabulary of mathematics and the sciences.[90]

Pluricentric English

Pie chart showing the percentage of native English speakers living in "inner circle" English-speaking countries. Native speakers are now substantially outnumbered worldwide by second-language speakers of English (not counted in this chart).

English is a pluricentric language, which means that no one national authority sets the standard for use of the language.[91][92][93][94] Spoken English, for example English used in broadcasting, generally follows national pronunciation standards that are also established by custom rather than by regulation. International broadcasters are usually identifiable as coming from one country rather than another through their accents,[95] but newsreader scripts are also composed largely in international standard written English. The norms of standard written English are maintained purely by the consensus of educated English-speakers around the world, without any oversight by any government or international organisation.[96]

American listeners generally readily understand most British broadcasting, and British listeners readily understand most American broadcasting. Most English speakers around the world can understand radio programmes, television programmes, and films from many parts of the English-speaking world.[97] Both standard and non-standard varieties of English can include both formal or informal styles, distinguished by word choice and syntax and use both technical and non-technical registers.[98]

The settlement history of the English-speaking inner circle countries outside Britain helped level dialect distinctions and produce koineised forms of English in South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand.[99] The majority of immigrants to the United States without British ancestry rapidly adopted English after arrival. Now the majority of the United States population are monolingual English speakers,[69][100] and English has been given official or co-official status by 30 of the 50 state governments, as well as all five territorial governments of the US, though there has never been an official language at the federal level.[101][102]

English as a global language

English has ceased to be an "English language" in the sense of belonging only to people who are ethnically English.[103][104] Use of English is growing country-by-country internally and for international communication. Most people learn English for practical rather than ideological reasons.[105] Many speakers of English in Africa have become part of an "Afro-Saxon" language community that unites Africans from different countries.[106]

As decolonisation proceeded throughout the British Empire in the 1950s and 1960s, former colonies often did not reject English but rather continued to use it as independent countries setting their own language policies.[54][55][107] For example, the view of the English language among many Indians has gone from associating it with colonialism to associating it with economic progress, and English continues to be an official language of India.[108] English is also widely used in media and literature, and the number of English language books published annually in India is the third largest in the world after the US and UK.[109] However English is rarely spoken as a first language, numbering only around a couple hundred-thousand people, and less than 5% of the population speak fluent English in India.[110][111] David Crystal claimed in 2004 that, combining native and non-native speakers, India now has more people who speak or understand English than any other country in the world,[112] but the number of English speakers in India is uncertain, with most scholars concluding that the United States still has more speakers of English than India.[113]

Modern English, sometimes described as the first global lingua franca,[57][114] is also regarded as the first world language.[115][116] English is the world's most widely used language in newspaper publishing, book publishing, international telecommunications, scientific publishing, international trade, mass entertainment, and diplomacy.[116] English is, by international treaty, the basis for the required controlled natural languages[117] Seaspeak and Airspeak, used as international languages of seafaring[118] and aviation.[119] English used to have parity with French and German in scientific research, but now it dominates that field.[120] It achieved parity with French as a language of diplomacy at the Treaty of Versailles negotiations in 1919.[121] By the time of the foundation of the United Nations at the end of World War II, English had become pre-eminent[122] and is now the main worldwide language of diplomacy and international relations.[123] It is one of six official languages of the United Nations.[124] Many other worldwide international organisations, including the International Olympic Committee, specify English as a working language or official language of the organisation.

Many regional international organisations such as the European Free Trade Association, Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN),[58] and Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) set English as their organisation's sole working language even though most members are not countries with a majority of native English speakers. While the European Union (EU) allows member states to designate any of the national languages as an official language of the Union, in practice English is the main working language of EU organisations.[125]

Although in most countries English is not an official language, it is currently the language most often taught as a foreign language.[57][58] In the countries of the EU, English is the most widely spoken foreign language in nineteen of the twenty-five member states where it is not an official language (that is, the countries other than Ireland and Malta). In a 2012 official Eurobarometer poll (conducted when the UK was still a member of the EU), 38 percent of the EU respondents outside the countries where English is an official language said they could speak English well enough to have a conversation in that language. The next most commonly mentioned foreign language, French (which is the most widely known foreign language in the UK and Ireland), could be used in conversation by 12 percent of respondents.[126]

A working knowledge of English has become a requirement in a number of occupations and professions such as medicine and computing. English has become so important in scientific publishing that more than 80 percent of all scientific journal articles indexed by Chemical Abstracts in 1998 were written in English, as were 90 percent of all articles in natural science publications by 1996 and 82 percent of articles in humanities publications by 1995.[128]

International communities such as international business people may use English as an auxiliary language, with an emphasis on vocabulary suitable for their domain of interest. This has led some scholars to develop the study of English as an auxiliary language. The trademarked Globish uses a relatively small subset of English vocabulary (about 1500 words, designed to represent the highest use in international business English) in combination with the standard English grammar.[129] Other examples include Simple English.

The increased use of the English language globally has had an effect on other languages, leading to some English words being assimilated into the vocabularies of other languages. This influence of English has led to concerns about language death,[130] and to claims of linguistic imperialism,[131] and has provoked resistance to the spread of English; however the number of speakers continues to increase because many people around the world think that English provides them with opportunities for better employment and improved lives.[132]

Although some scholars mention a possibility of future divergence of English dialects into mutually unintelligible languages, most think a more likely outcome is that English will continue to function as a koineised language in which the standard form unifies speakers from around the world.[133] English is used as the language for wider communication in countries around the world.[134] Thus English has grown in worldwide use much more than any constructed language proposed as an international auxiliary language, including Esperanto.[135][136]

Phonology

The phonetics and phonology of the English language differ from one dialect to another, usually without interfering with mutual communication. Phonological variation affects the inventory of phonemes (i.e. speech sounds that distinguish meaning), and phonetic variation consists in differences in pronunciation of the phonemes. [137] This overview mainly describes the standard pronunciations of the United Kingdom and the United States: Received Pronunciation (RP) and General American (GA). (See § Dialects, accents and varieties, below.)

The phonetic symbols used below are from the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA).[138][139][140]

Consonants

Most English dialects share the same 24 consonant phonemes. The consonant inventory shown below is valid for California English,[141] and for RP.[142]

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | |||||||||||

| Stop | p | b | t | d | k | ɡ | ||||||||

| Affricate | tʃ | dʒ | ||||||||||||

| Fricative | f | v | θ | ð | s | z | ʃ | ʒ | h | |||||

| Approximant | l | ɹ* | j | w | ||||||||||

* Conventionally transcribed /r/

In the table, when obstruents (stops, affricates, and fricatives) appear in pairs, such as /p b/, /tʃ dʒ/, and /s z/, the first is fortis (strong) and the second is lenis (weak). Fortis obstruents, such as /p tʃ s/ are pronounced with more muscular tension and breath force than lenis consonants, such as /b dʒ z/, and are always voiceless. Lenis consonants are partly voiced at the beginning and end of utterances, and fully voiced between vowels. Fortis stops such as /p/ have additional articulatory or acoustic features in most dialects: they are aspirated [pʰ] when they occur alone at the beginning of a stressed syllable, often unaspirated in other cases, and often unreleased [p̚] or pre-glottalised [ʔp] at the end of a syllable. In a single-syllable word, a vowel before a fortis stop is shortened: thus nip has a noticeably shorter vowel (phonetically, but not phonemically) than nib [nɪˑb̥] (see below).[143]

- lenis stops: bin [b̥ɪˑn], about [əˈbaʊt], nib [nɪˑb̥]

- fortis stops: pin [pʰɪn]; spin [spɪn]; happy [ˈhæpi]; nip [nɪp̚] or [nɪʔp]

In RP, the lateral approximant /l/, has two main allophones (pronunciation variants): the clear or plain [l], as in light, and the dark or velarised [ɫ], as in full.[144] GA has dark l in most cases.[145]

- clear l: RP light [laɪt]

- dark l: RP and GA full [fʊɫ], GA light [ɫaɪt]

All sonorants (liquids /l, r/ and nasals /m, n, ŋ/) devoice when following a voiceless obstruent, and they are syllabic when following a consonant at the end of a word.[146]

- voiceless sonorants: clay [kl̥eɪ̯]; snow RP [sn̥əʊ̯], GA [sn̥oʊ̯]

- syllabic sonorants: paddle [ˈpad.l̩], button [ˈbʌt.n̩]

Vowels

The pronunciation of vowels varies a great deal between dialects and is one of the most detectable aspects of a speaker's accent. The table below lists the vowel phonemes in Received Pronunciation (RP) and General American (GA), with examples of words in which they occur from lexical sets compiled by linguists. The vowels are represented with symbols from the International Phonetic Alphabet; those given for RP are standard in British dictionaries and other publications.[147]

| RP | GA | Word |

|---|---|---|

| iː | i | need |

| ɪ | bid | |

| e | ɛ | bed |

| æ | back | |

| ɑː | ɑ | bra |

| ɒ | box | |

| ɔ, ɑ | cloth | |

| ɔː | paw | |

| uː | u | food |

| ʊ | good | |

| ʌ | but | |

| ɜː | ɜɹ | bird |

| ə | comma | |

| RP | GA | Word |

|---|---|---|

| eɪ | bay | |

| əʊ | oʊ | road |

| aɪ | cry | |

| aʊ | cow | |

| ɔɪ | boy | |

| RP | GA | Word |

|---|---|---|

| ɪə | ɪɹ | peer |

| eə | ɛɹ | pair |

| ʊə | ʊɹ | poor |

In RP, vowel length is phonemic; long vowels are marked with a triangular colon ⟨ː⟩ in the table above, such as the vowel of need [niːd] as opposed to bid [bɪd]. In GA, vowel length is non-distinctive.

In both RP and GA, vowels are phonetically shortened before fortis consonants in the same syllable, like /t tʃ f/, but not before lenis consonants like /d dʒ v/ or in open syllables: thus, the vowels of rich [rɪtʃ], neat [nit], and safe [seɪ̯f] are noticeably shorter than the vowels of ridge [rɪˑdʒ], need [niˑd], and save [seˑɪ̯v], and the vowel of light [laɪ̯t] is shorter than that of lie [laˑɪ̯]. Because lenis consonants are frequently voiceless at the end of a syllable, vowel length is an important cue as to whether the following consonant is lenis or fortis.[148]

The vowel /ə/ only occurs in unstressed syllables and is more open in quality in stem-final positions.[149][150] Some dialects do not contrast /ɪ/ and /ə/ in unstressed positions, so that rabbit and abbot rhyme and Lenin and Lennon are homophonous, a dialect feature called weak vowel merger.[151] GA /ɜr/ and /ər/ are realised as an r-coloured vowel [ɚ], as in further [ˈfɚðɚ] (phonemically /ˈfɜrðər/), which in RP is realised as [ˈfəːðə] (phonemically /ˈfɜːðə/).[152]

Phonotactics

An English syllable includes a syllable nucleus consisting of a vowel sound. Syllable onset and coda (start and end) are optional. A syllable can start with up to three consonant sounds, as in sprint /sprɪnt/, and end with up to five, as in (for some dialects) angsts /aŋksts/. This gives an English syllable the following structure, (CCC)V(CCCCC), where C represents a consonant and V a vowel; the word strengths /strɛŋkθs/ is thus close to the most complex syllable possible in English. The consonants that may appear together in onsets or codas are restricted, as is the order in which they may appear. Onsets can only have four types of consonant clusters: a stop and approximant, as in play; a voiceless fricative and approximant, as in fly or sly; s and a voiceless stop, as in stay; and s, a voiceless stop, and an approximant, as in string.[153] Clusters of nasal and stop are only allowed in codas. Clusters of obstruents always agree in voicing, and clusters of sibilants and of plosives with the same point of articulation are prohibited. Furthermore, several consonants have limited distributions: /h/ can only occur in syllable-initial position, and /ŋ/ only in syllable-final position.[154]

Stress, rhythm and intonation

Stress plays an important role in English. Certain syllables are stressed, while others are unstressed. Stress is a combination of duration, intensity, vowel quality, and sometimes changes in pitch. Stressed syllables are pronounced longer and louder than unstressed syllables, and vowels in unstressed syllables are frequently reduced while vowels in stressed syllables are not.[155] Some words, primarily short function words but also some modal verbs such as can, have weak and strong forms depending on whether they occur in stressed or non-stressed position within a sentence.

Stress in English is phonemic, and some pairs of words are distinguished by stress. For instance, the word contract is stressed on the first syllable (/ˈkɒntrækt/ KON-trakt) when used as a noun, but on the last syllable (/kənˈtrækt/ kən-TRAKT) for most meanings (for example, "reduce in size") when used as a verb.[156][157][158] Here stress is connected to vowel reduction: in the noun "contract" the first syllable is stressed and has the unreduced vowel /ɒ/, but in the verb "contract" the first syllable is unstressed and its vowel is reduced to /ə/. Stress is also used to distinguish between words and phrases, so that a compound word receives a single stress unit, but the corresponding phrase has two: e.g. a burnout (/ˈbɜːrnaʊt/) versus to burn out (/ˈbɜːrn ˈaʊt/), and a hotdog (/ˈhɒtdɒɡ/) versus a hot dog (/ˈhɒt ˈdɒɡ/).[159]

In terms of rhythm, English is generally described as a stress-timed language, meaning that the amount of time between stressed syllables tends to be equal.[160] Stressed syllables are pronounced longer, but unstressed syllables (syllables between stresses) are shortened. Vowels in unstressed syllables are shortened as well, and vowel shortening causes changes in vowel quality: vowel reduction.[161]

Regional variation

| Phonological features | United States | Canada | Republic of Ireland | Northern Ireland | Scotland | England | Wales | South Africa | Australia | New Zealand |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| father–bother merger | yes | yes | ||||||||

| /ɒ/ is unrounded | yes | yes | yes | |||||||

| /ɜːr/ is pronounced [ɚ] | yes | yes | yes | yes | ||||||

| cot–caught merger | possibly | yes | possibly | yes | yes | |||||

| fool–full merger | yes | yes | ||||||||

| /t, d/ flapping | yes | yes | possibly | often | rarely | rarely | rarely | rarely | yes | often |

| trap–bath split | possibly | possibly | often | yes | yes | often | yes | |||

| non-rhotic (/r/-dropping after vowels) | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | |||||

| close vowels for /æ, ɛ/ | yes | yes | yes | |||||||

| /l/ can always be pronounced [ɫ] | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | ||||

| /ɑːr/ is fronted | possibly | possibly | yes | yes |

| Lexical set | RP | GA | Can | Sound change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| THOUGHT | /ɔː/ | /ɔ/ or /ɑ/ | /ɑ/ | cot–caught merger |

| CLOTH | /ɒ/ | lot–cloth split | ||

| LOT | /ɑ/ | father–bother merger | ||

| PALM | /ɑː/ | |||

| BATH | /æ/ | /æ/ | trap–bath split | |

| TRAP | /æ/ |

Varieties of English vary the most in pronunciation of vowels. The best known national varieties used as standards for education in non-English-speaking countries are British (BrE) and American (AmE). Countries such as Canada, Australia, Ireland, New Zealand and South Africa have their own standard varieties which are less often used as standards for education internationally. Some differences between the various dialects are shown in the table "Varieties of Standard English and their features".[162]

English has undergone many historical sound changes, some of them affecting all varieties, and others affecting only a few. Most standard varieties are affected by the Great Vowel Shift, which changed the pronunciation of long vowels, but a few dialects have slightly different results. In North America, a number of chain shifts such as the Northern Cities Vowel Shift and Canadian Shift have produced very different vowel landscapes in some regional accents.[163]

Some dialects have fewer or more consonant phonemes and phones than the standard varieties. Some conservative varieties like Scottish English have a voiceless [ʍ] sound in whine that contrasts with the voiced [w] in wine, but most other dialects pronounce both words with voiced [w], a dialect feature called wine–whine merger. The unvoiced velar fricative sound /x/ is found in Scottish English, which distinguishes loch /lɔx/ from lock /lɔk/. Accents like Cockney with "h-dropping" lack the glottal fricative /h/, and dialects with th-stopping and th-fronting like African American Vernacular and Estuary English do not have the dental fricatives /θ, ð/, but replace them with dental or alveolar stops /t, d/ or labiodental fricatives /f, v/.[164][165] Other changes affecting the phonology of local varieties are processes such as yod-dropping, yod-coalescence, and reduction of consonant clusters.[166]

General American and Received Pronunciation vary in their pronunciation of historical /r/ after a vowel at the end of a syllable (in the syllable coda). GA is a rhotic dialect, meaning that it pronounces /r/ at the end of a syllable, but RP is non-rhotic, meaning that it loses /r/ in that position. English dialects are classified as rhotic or non-rhotic depending on whether they elide /r/ like RP or keep it like GA.[167]

There is complex dialectal variation in words with the open front and open back vowels /æ ɑː ɒ ɔː/. These four vowels are only distinguished in RP, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. In GA, these vowels merge to three /æ ɑ ɔ/,[168] and in Canadian English, they merge to two /æ ɑ/.[169] In addition, the words that have each vowel vary by dialect. The table "Dialects and open vowels" shows this variation with lexical sets in which these sounds occur.

Grammar

As is typical of an Indo-European language, English follows accusative morphosyntactic alignment. Unlike other Indo-European languages though, English has largely abandoned the inflectional case system in favour of analytic constructions. Only the personal pronouns retain morphological case more strongly than any other word class. English distinguishes at least seven major word classes: verbs, nouns, adjectives, adverbs, determiners (including articles), prepositions, and conjunctions. Some analyses add pronouns as a class separate from nouns, and subdivide conjunctions into subordinators and coordinators, and add the class of interjections.[170] English also has a rich set of auxiliary verbs, such as have and do, expressing the categories of mood and aspect. Questions are marked by do-support, wh-movement (fronting of question words beginning with wh-) and word order inversion with some verbs.[171]

Some traits typical of Germanic languages persist in English, such as the distinction between irregularly inflected strong stems inflected through ablaut (i.e. changing the vowel of the stem, as in the pairs speak/spoke and foot/feet) and weak stems inflected through affixation (such as love/loved, hand/hands).[172] Vestiges of the case and gender system are found in the pronoun system (he/him, who/whom) and in the inflection of the copula verb to be.[172]

The seven word-classes are exemplified in this sample sentence:[173]

| The | chairman | of | the | committee | and | the | loquacious | politician | clashed | violently | when | the | meeting | started. |

| Det. | Noun | Prep. | Det. | Noun | Conj. | Det. | Adj. | Noun | Verb | Advb. | Conj. | Det. | Noun | Verb |

Nouns and noun phrases

English nouns are only inflected for number and possession. New nouns can be formed through derivation or compounding. They are semantically divided into proper nouns (names) and common nouns. Common nouns are in turn divided into concrete and abstract nouns, and grammatically into count nouns and mass nouns.[174]

Most count nouns are inflected for plural number through the use of the plural suffix -s, but a few nouns have irregular plural forms. Mass nouns can only be pluralised through the use of a count noun classifier, e.g. one loaf of bread, two loaves of bread.[175]

Regular plural formation:

- Singular: cat, dog

- Plural: cats, dogs

Irregular plural formation:

- Singular: man, woman, foot, fish, ox, knife, mouse

- Plural: men, women, feet, fish, oxen, knives, mice

Possession can be expressed either by the possessive enclitic -s (also traditionally called a genitive suffix), or by the preposition of. Historically the -s possessive has been used for animate nouns, whereas the of possessive has been reserved for inanimate nouns. Today this distinction is less clear, and many speakers use -s also with inanimates. Orthographically the possessive -s is separated from a singular noun with an apostrophe. If the noun is plural formed with -s the apostrophe follows the -s.[171]

Possessive constructions:

- With -s: The woman's husband's child

- With of: The child of the husband of the woman

Nouns can form noun phrases (NPs) where they are the syntactic head of the words that depend on them such as determiners, quantifiers, conjunctions or adjectives.[176] Noun phrases can be short, such as the man, composed only of a determiner and a noun. They can also include modifiers such as adjectives (e.g. red, tall, all) and specifiers such as determiners (e.g. the, that). But they can also tie together several nouns into a single long NP, using conjunctions such as and, or prepositions such as with, e.g. the tall man with the long red trousers and his skinny wife with the spectacles (this NP uses conjunctions, prepositions, specifiers, and modifiers). Regardless of length, an NP functions as a syntactic unit.[171] For example, the possessive enclitic can, in cases which do not lead to ambiguity, follow the entire noun phrase, as in The President of India's wife, where the enclitic follows India and not President.

The class of determiners is used to specify the noun they precede in terms of definiteness, where the marks a definite noun and a or an an indefinite one. A definite noun is assumed by the speaker to be already known by the interlocutor, whereas an indefinite noun is not specified as being previously known. Quantifiers, which include one, many, some and all, are used to specify the noun in terms of quantity or number. The noun must agree with the number of the determiner, e.g. one man (sg.) but all men (pl.). Determiners are the first constituents in a noun phrase.[177]

Adjectives

Adjectives modify a noun by providing additional information about their referents. In English, adjectives come before the nouns they modify and after determiners.[178] In Modern English, adjectives are not inflected so as to agree in form with the noun they modify, as adjectives in most other Indo-European languages do. For example, in the phrases the slender boy, and many slender girls, the adjective slender does not change form to agree with either the number or gender of the noun.

Some adjectives are inflected for degree of comparison, with the positive degree unmarked, the suffix -er marking the comparative, and -est marking the superlative: a small boy, the boy is smaller than the girl, that boy is the smallest. Some adjectives have irregular comparative and superlative forms, such as good, better, and best. Other adjectives have comparatives formed by periphrastic constructions, with the adverb more marking the comparative, and most marking the superlative: happier or more happy, the happiest or most happy.[179] There is some variation among speakers regarding which adjectives use inflected or periphrastic comparison, and some studies have shown a tendency for the periphrastic forms to become more common at the expense of the inflected form.[180]

Pronouns, case, and person

English pronouns conserve many traits of case and gender inflection. The personal pronouns retain a difference between subjective and objective case in most persons (I/me, he/him, she/her, we/us, they/them) as well as an animateness distinction in the third person singular (distinguishing it from the three sets of animate third person singular pronouns) and an optional gender distinction in the animate third person singular (distinguishing between she/her [feminine], they/them [neuter], and he/him [masculine]).[181][182] The subjective case corresponds to the Old English nominative case, and the objective case is used in the sense both of the previous accusative case (for a patient, or direct object of a transitive verb), and of the Old English dative case (for a recipient or indirect object of a transitive verb).[183][184] The subjective is used when the pronoun is the subject of a finite clause, otherwise the objective is used.[185] While grammarians such as Henry Sweet[186] and Otto Jespersen[187] noted that the English cases did not correspond to the traditional Latin-based system, some contemporary grammars, for example Huddleston & Pullum (2002), retain traditional labels for the cases, calling them nominative and accusative cases respectively.

Possessive pronouns exist in dependent and independent forms; the dependent form functions as a determiner specifying a noun (as in my chair), while the independent form can stand alone as if it were a noun (e.g. the chair is mine).[188] The English system of grammatical person no longer has a distinction between formal and informal pronouns of address (the old second person singular familiar pronoun thou acquired a pejorative or inferior tinge of meaning and was abandoned).

Both the second and third persons share pronouns between the plural and singular:

- Plural and singular are always identical (you, your, yours) in the second person (except in the reflexive form: yourself/yourselves) in most dialects. Some dialects have introduced innovative second person plural pronouns, such as y'all (found in Southern American English and African American (Vernacular) English), youse (found in Australian English), or ye (in Hiberno-English).

- In the third person, the they/them series of pronouns (they, them, their, theirs, themselves) are used in both plural and singular, and are the only pronouns available for the plural. In the singular, the they/them series (sometimes with the addition of the singular-specific reflexive form themself) serve as a gender-neutral set of pronouns, alongside the feminine she/her series and the masculine he/him series.[181][182][189][190][191][192][193]

| Person | Subjective case | Objective case | Dependent possessive | Independent possessive | Reflexive |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st p. sg. | I | me | my | mine | myself |

| 2nd p. sg. | you | you | your | yours | yourself |

| 3rd p. sg. | he/she/it/they | him/her/it/them | his/her/its/their | his/hers/its/theirs | himself/herself/itself/themself/themselves |

| 1st p. pl. | we | us | our | ours | ourselves |

| 2nd p. pl. | you | you | your | yours | yourselves |

| 3rd p. pl. | they | them | their | theirs | themselves |

Pronouns are used to refer to entities deictically or anaphorically. A deictic pronoun points to some person or object by identifying it relative to the speech situation—for example, the pronoun I identifies the speaker, and the pronoun you, the addressee. Anaphoric pronouns such as that refer back to an entity already mentioned or assumed by the speaker to be known by the audience, for example in the sentence I already told you that. The reflexive pronouns are used when the oblique argument is identical to the subject of a phrase (e.g. "he sent it to himself" or "she braced herself for impact").[194]

Prepositions

Prepositional phrases (PP) are phrases composed of a preposition and one or more nouns, e.g. with the dog, for my friend, to school, in England.[195] Prepositions have a wide range of uses in English. They are used to describe movement, place, and other relations between different entities, but they also have many syntactic uses such as introducing complement clauses and oblique arguments of verbs.[195] For example, in the phrase I gave it to him, the preposition to marks the recipient, or Indirect Object of the verb to give. Traditionally words were only considered prepositions if they governed the case of the noun they preceded, for example causing the pronouns to use the objective rather than subjective form, "with her", "to me", "for us". But some contemporary grammars such as that of Huddleston & Pullum (2002:598–600) no longer consider government of case to be the defining feature of the class of prepositions, rather defining prepositions as words that can function as the heads of prepositional phrases.

Verbs and verb phrases

English verbs are inflected for tense and aspect and marked for agreement with present-tense third-person singular subject. Only the copula verb to be is still inflected for agreement with the plural and first and second person subjects.[179] Auxiliary verbs such as have and be are paired with verbs in the infinitive, past, or progressive forms. They form complex tenses, aspects, and moods. Auxiliary verbs differ from other verbs in that they can be followed by the negation, and in that they can occur as the first constituent in a question sentence.[196][197]

Most verbs have six inflectional forms. The primary forms are a plain present, a third-person singular present, and a preterite (past) form. The secondary forms are a plain form used for the infinitive, a gerund-participle and a past participle.[198] The copula verb to be is the only verb to retain some of its original conjugation, and takes different inflectional forms depending on the subject. The first-person present-tense form is am, the third person singular form is is, and the form are is used in the second-person singular and all three plurals. The only verb past participle is been and its gerund-participle is being.

| Inflection | Strong | Regular |

|---|---|---|

| Plain present | take | love |

| 3rd person sg. present |

takes | loves |

| Preterite | took | loved |

| Plain (infinitive) | take | love |

| Gerund–participle | taking | loving |

| Past participle | taken | loved |

Tense, aspect and mood

English has two primary tenses, past (preterite) and non-past. The preterite is inflected by using the preterite form of the verb, which for the regular verbs includes the suffix -ed, and for the strong verbs either the suffix -t or a change in the stem vowel. The non-past form is unmarked except in the third person singular, which takes the suffix -s.[196]

| Present | Preterite | |

|---|---|---|

| First person | I run | I ran |

| Second person | You run | You ran |

| Third person | John runs | John ran |

English does not have future verb forms.[199] The future tense is expressed periphrastically with one of the auxiliary verbs will or shall.[200] Many varieties also use a near future constructed with the phrasal verb be going to ("going-to future").[201]

| Future | |

|---|---|

| First person | I will run |

| Second person | You will run |

| Third person | John will run |

Further aspectual distinctions are shown by auxiliary verbs, primarily have and be, which show the contrast between a perfect and non-perfect past tense (I have run vs. I was running), and compound tenses such as preterite perfect (I had been running) and present perfect (I have been running).[202]

For the expression of mood, English uses a number of modal auxiliaries, such as can, may, will, shall and the past tense forms could, might, would, should. There are also subjunctive and imperative moods, both based on the plain form of the verb (i.e. without the third person singular -s), for use in subordinate clauses (e.g. subjunctive: It is important that he run every day; imperative Run!).[200]

An infinitive form, that uses the plain form of the verb and the preposition to, is used for verbal clauses that are syntactically subordinate to a finite verbal clause. Finite verbal clauses are those that are formed around a verb in the present or preterite form. In clauses with auxiliary verbs, they are the finite verbs and the main verb is treated as a subordinate clause.[203] For example, he has to go where only the auxiliary verb have is inflected for time and the main verb to go is in the infinitive, or in a complement clause such as I saw him leave, where the main verb is to see, which is in a preterite form, and leave is in the infinitive.

Phrasal verbs

English also makes frequent use of constructions traditionally called phrasal verbs, verb phrases that are made up of a verb root and a preposition or particle that follows the verb. The phrase then functions as a single predicate. In terms of intonation the preposition is fused to the verb, but in writing it is written as a separate word. Examples of phrasal verbs are to get up, to ask out, to back up, to give up, to get together, to hang out, to put up with, etc. The phrasal verb frequently has a highly idiomatic meaning that is more specialised and restricted than what can be simply extrapolated from the combination of verb and preposition complement (e.g. lay off meaning terminate someone's employment).[204] In spite of the idiomatic meaning, some grammarians, including Huddleston & Pullum (2002:274), do not consider this type of construction to form a syntactic constituent and hence refrain from using the term "phrasal verb". Instead, they consider the construction simply to be a verb with a prepositional phrase as its syntactic complement, i.e. he woke up in the morning and he ran up in the mountains are syntactically equivalent.

Adverbs

The function of adverbs is to modify the action or event described by the verb by providing additional information about the manner in which it occurs.[171] Many adverbs are derived from adjectives by appending the suffix -ly. For example, in the phrase the woman walked quickly, the adverb quickly is derived in this way from the adjective quick. Some commonly used adjectives have irregular adverbial forms, such as good, which has the adverbial form well.

Syntax

Modern English syntax language is moderately analytic.[205] It has developed features such as modal verbs and word order as resources for conveying meaning. Auxiliary verbs mark constructions such as questions, negative polarity, the passive voice and progressive aspect.

Basic constituent order

English word order has moved from the Germanic verb-second (V2) word order to being almost exclusively subject–verb–object (SVO).[206] The combination of SVO order and use of auxiliary verbs often creates clusters of two or more verbs at the centre of the sentence, such as he had hoped to try to open it.

In most sentences, English only marks grammatical relations through word order.[207] The subject constituent precedes the verb and the object constituent follows it. The example below demonstrates how the grammatical roles of each constituent are marked only by the position relative to the verb:

| The dog | bites | the man |

| S | V | O |

| The man | bites | the dog |

| S | V | O |

An exception is found in sentences where one of the constituents is a pronoun, in which case it is doubly marked, both by word order and by case inflection, where the subject pronoun precedes the verb and takes the subjective case form, and the object pronoun follows the verb and takes the objective case form.[208] The example below demonstrates this double marking in a sentence where both object and subject are represented with a third person singular masculine pronoun:

| He | hit | him |

| S | V | O |

Indirect objects (IO) of ditransitive verbs can be placed either as the first object in a double object construction (S V IO O), such as I gave Jane the book or in a prepositional phrase, such as I gave the book to Jane.[209]

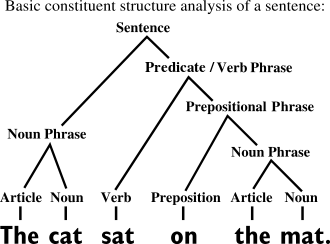

Clause syntax

In English a sentence may be composed of one or more clauses, that may, in turn, be composed of one or more phrases (e.g. Noun Phrases, Verb Phrases, and Prepositional Phrases). A clause is built around a verb and includes its constituents, such as any NPs and PPs. Within a sentence, there is always at least one main clause (or matrix clause) whereas other clauses are subordinate to a main clause. Subordinate clauses may function as arguments of the verb in the main clause. For example, in the phrase I think (that) you are lying, the main clause is headed by the verb think, the subject is I, but the object of the phrase is the subordinate clause (that) you are lying. The subordinating conjunction that shows that the clause that follows is a subordinate clause, but it is often omitted.[210] Relative clauses are clauses that function as a modifier or specifier to some constituent in the main clause: For example, in the sentence I saw the letter that you received today, the relative clause that you received today specifies the meaning of the word letter, the object of the main clause. Relative clauses can be introduced by the pronouns who, whose, whom and which as well as by that (which can also be omitted.)[211] In contrast to many other Germanic languages there are no major differences between word order in main and subordinate clauses.[212]

Auxiliary verb constructions

English syntax relies on auxiliary verbs for many functions including the expression of tense, aspect, and mood. Auxiliary verbs form main clauses, and the main verbs function as heads of a subordinate clause of the auxiliary verb. For example, in the sentence the dog did not find its bone, the clause find its bone is the complement of the negated verb did not. Subject–auxiliary inversion is used in many constructions, including focus, negation, and interrogative constructions.

The verb do can be used as an auxiliary even in simple declarative sentences, where it usually serves to add emphasis, as in "I did shut the fridge." However, in the negated and inverted clauses referred to above, it is used because the rules of English syntax permit these constructions only when an auxiliary is present. Modern English does not allow the addition of the negating adverb not to an ordinary finite lexical verb, as in *I know not—it can only be added to an auxiliary (or copular) verb, hence if there is no other auxiliary present when negation is required, the auxiliary do is used, to produce a form like I do not (don't) know. The same applies in clauses requiring inversion, including most questions—inversion must involve the subject and an auxiliary verb, so it is not possible to say *Know you him?; grammatical rules require Do you know him?[213]

Negation is done with the adverb not, which precedes the main verb and follows an auxiliary verb. A contracted form of not -n't can be used as an enclitic attaching to auxiliary verbs and to the copula verb to be. Just as with questions, many negative constructions require the negation to occur with do-support, thus in Modern English I don't know him is the correct answer to the question Do you know him?, but not *I know him not, although this construction may be found in older English.[214]

Passive constructions also use auxiliary verbs. A passive construction rephrases an active construction in such a way that the object of the active phrase becomes the subject of the passive phrase, and the subject of the active phrase is either omitted or demoted to a role as an oblique argument introduced in a prepositional phrase. They are formed by using the past participle either with the auxiliary verb to be or to get, although not all varieties of English allow the use of passives with get. For example, putting the sentence she sees him into the passive becomes he is seen (by her), or he gets seen (by her).[215]

Questions

Both yes–no questions and wh-questions in English are mostly formed using subject–auxiliary inversion (Am I going tomorrow?, Where can we eat?), which may require do-support (Do you like her?, Where did he go?). In most cases, interrogative words (wh-words; e.g. what, who, where, when, why, how) appear in a fronted position. For example, in the question What did you see?, the word what appears as the first constituent despite being the grammatical object of the sentence. (When the wh-word is the subject or forms part of the subject, no inversion occurs: Who saw the cat?.) Prepositional phrases can also be fronted when they are the question's theme, e.g. To whose house did you go last night?. The personal interrogative pronoun who is the only interrogative pronoun to still show inflection for case, with the variant whom serving as the objective case form, although this form may be going out of use in many contexts.[216]

Discourse level syntax

While English is a subject-prominent language, at the discourse level it tends to use a topic-comment structure, where the known information (topic) precedes the new information (comment). Because of the strict SVO syntax, the topic of a sentence generally has to be the grammatical subject of the sentence. In cases where the topic is not the grammatical subject of the sentence, it is often promoted to subject position through syntactic means. One way of doing this is through a passive construction, the girl was stung by the bee. Another way is through a cleft sentence where the main clause is demoted to be a complement clause of a copula sentence with a dummy subject such as it or there, e.g. it was the girl that the bee stung, there was a girl who was stung by a bee.[217] Dummy subjects are also used in constructions where there is no grammatical subject such as with impersonal verbs (e.g., it is raining) or in existential clauses (there are many cars on the street). Through the use of these complex sentence constructions with informationally vacuous subjects, English is able to maintain both a topic-comment sentence structure and a SVO syntax.

Focus constructions emphasise a particular piece of new or salient information within a sentence, generally through allocating the main sentence level stress on the focal constituent. For example, the girl was stung by a bee (emphasising it was a bee and not, for example, a wasp that stung her), or The girl was stung by a bee (contrasting with another possibility, for example that it was the boy).[218] Topic and focus can also be established through syntactic dislocation, either preposing or postposing the item to be focused on relative to the main clause. For example, That girl over there, she was stung by a bee, emphasises the girl by preposition, but a similar effect could be achieved by postposition, she was stung by a bee, that girl over there, where reference to the girl is established as an "afterthought".[219]

Cohesion between sentences is achieved through the use of deictic pronouns as anaphora (e.g. that is exactly what I mean where that refers to some fact known to both interlocutors, or then used to locate the time of a narrated event relative to the time of a previously narrated event).[220] Discourse markers such as oh, so or well, also signal the progression of ideas between sentences and help to create cohesion. Discourse markers are often the first constituents in sentences. Discourse markers are also used for stance taking in which speakers position themselves in a specific attitude towards what is being said, for example, no way is that true! (the idiomatic marker no way! expressing disbelief), or boy! I'm hungry (the marker boy expressing emphasis). While discourse markers are particularly characteristic of informal and spoken registers of English, they are also used in written and formal registers.[221]

Vocabulary

It is generally stated that English has around 170,000 words, or 220,000 if obsolete words are counted; this estimate is based on the last full edition of the Oxford English Dictionary from 1989.[222] Over half of these words are nouns, a quarter adjectives, and a seventh verbs. There is one count that puts the English vocabulary at about 1 million words—but that count presumably includes words such as Latin species names, scientific terminology, botanical terms, prefixed and suffixed words, jargon, foreign words of extremely limited English use, and technical acronyms.[223]

Due to its status as an international language, English adopts foreign words quickly, and borrows vocabulary from many other sources. Early studies of English vocabulary by lexicographers, the scholars who formally study vocabulary, compile dictionaries, or both, were impeded by a lack of comprehensive data on actual vocabulary in use from good-quality linguistic corpora,[224] collections of actual written texts and spoken passages. Many statements published before the end of the 20th century about the growth of English vocabulary over time, the dates of first use of various words in English, and the sources of English vocabulary will have to be corrected as new computerised analysis of linguistic corpus data becomes available.[223][225]

Word formation processes

English forms new words from existing words or roots in its vocabulary through a variety of processes. One of the most productive processes in English is conversion,[226] using a word with a different grammatical role, for example using a noun as a verb or a verb as a noun. Another productive word-formation process is nominal compounding,[223][225] producing compound words such as babysitter or ice cream or homesick.[226] A process more common in Old English than in Modern English, but still productive in Modern English, is the use of derivational suffixes (-hood, -ness, -ing, -ility) to derive new words from existing words (especially those of Germanic origin) or stems (especially for words of Latin or Greek origin).

Formation of new words, called neologisms, based on Greek and/or Latin roots (for example television or optometry) is a highly productive process in English and in most modern European languages, so much so that it is often difficult to determine in which language a neologism originated. For this reason, lexicographer Philip Gove attributed many such words to the "international scientific vocabulary" (ISV) when compiling Webster's Third New International Dictionary (1961). Another active word-formation process in English are acronyms,[227] words formed by pronouncing as a single word abbreviations of longer phrases, e.g. NATO, laser.

Word origins

English, besides forming new words from existing words and their roots, also borrows words from other languages. This adoption of words from other languages is commonplace in many world languages, but English has been especially open to borrowing of foreign words throughout the last 1,000 years.[229] The most commonly used words in English are West Germanic.[230] The words in English learned first by children as they learn to speak, particularly the grammatical words that dominate the word count of both spoken and written texts, are mainly the Germanic words inherited from the earliest periods of the development of Old English.[223]

But one of the consequences of long language contact between French and English in all stages of their development is that the vocabulary of English has a very high percentage of "Latinate" words (derived from French, especially, and also from other Romance languages and Latin). French words from various periods of the development of French now make up one-third of the vocabulary of English.[231] Linguist Anthony Lacoudre estimated that over 40,000 English words are of French origin and may be understood without orthographical change by French speakers.[232] Words of Old Norse origin have entered the English language primarily from the contact between Old Norse and Old English during colonisation of eastern and northern England. Many of these words are part of English core vocabulary, such as egg and knife.[233]

English has also borrowed many words directly from Latin, the ancestor of the Romance languages, during all stages of its development.[225][223] Many of these words had earlier been borrowed into Latin from Greek. Latin or Greek are still highly productive sources of stems used to form vocabulary of subjects learned in higher education such as the sciences, philosophy, and mathematics.[234] English continues to gain new loanwords and calques ("loan translations") from languages all over the world, and words from languages other than the ancestral Anglo-Saxon language make up about 60% of the vocabulary of English.[235]

English has formal and informal speech registers; informal registers, including child-directed speech, tend to be made up predominantly of words of Anglo-Saxon origin, while the percentage of vocabulary that is of Latinate origin is higher in legal, scientific, and academic texts.[236][237]

English loanwords and calques in other languages

English has had a strong influence on the vocabulary of other languages.[231][238] The influence of English comes from such factors as opinion leaders in other countries knowing the English language, the role of English as a world lingua franca, and the large number of books and films that are translated from English into other languages.[239] That pervasive use of English leads to a conclusion in many places that English is an especially suitable language for expressing new ideas or describing new technologies. Among varieties of English, it is especially American English that influences other languages.[240] Some languages, such as Chinese, write words borrowed from English mostly as calques, while others, such as Japanese, readily take in English loanwords written in sound-indicating script.[241] Dubbed films and television programmes are an especially fruitful source of English influence on languages in Europe.[241]

Writing system

Since the ninth century, English has been written in a Latin alphabet (also called Roman alphabet). Earlier Old English texts in Anglo-Saxon runes are only short inscriptions. The great majority of literary works in Old English that survive to today are written in the Roman alphabet.[36] The modern English alphabet contains 26 letters of the Latin script: a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j, k, l, m, n, o, p, q, r, s, t, u, v, w, x, y, z (which also have capital forms: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, L, M, N, O, P, Q, R, S, T, U, V, W, X, Y, Z).