Femur

The femur (/ˈfiːmər/; pl. femurs or femora /ˈfɛmərə/),[1][2] or thigh bone, is the proximal bone of the hindlimb in tetrapod vertebrates. The head of the femur articulates with the acetabulum in the pelvic bone forming the hip joint, while the distal part of the femur articulates with the tibia (shinbone) and patella (kneecap), forming the knee joint. By most measures the two (left and right) femurs are the strongest bones of the body, and in humans, the largest and thickest.

| Femur | |

|---|---|

Position of femur (shown in red) | |

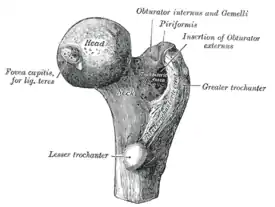

Left femur seen from behind. | |

| Details | |

| Origins | Gastrocnemius, vastus lateralis, vastus medialis and vastus intermedius |

| Insertions | Gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, iliopsoas, lateral rotator group, adductors of the hip |

| Articulations | hip: acetabulum of pelvis superiorly knee: with the tibia and patella inferiorly |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Os femoris, os longissimum |

| MeSH | D005269 |

| TA98 | A02.5.04.001 |

| TA2 | 1360 |

| FMA | 9611 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

Structure

The femur is the only bone in the upper leg. The two femurs converge medially toward the knees, where they articulate with the proximal ends of the tibiae. The angle of convergence of the femora is a major factor in determining the femoral-tibial angle. Human females have thicker pelvic bones, causing their femora to converge more than in males.

In the condition genu valgum (knock knee) the femurs converge so much that the knees touch one another. The opposite extreme is genu varum (bow-leggedness). In the general population of people without either genu valgum or genu varum, the femoral-tibial angle is about 175 degrees.[3]

The femur is the largest and thickest bone in the human body. By some measures, it is also the strongest bone in the human body. This depends on the type of measurement taken to calculate strength. Some strength tests show the temporal bone in the skull to be the strongest bone. The femur length on average is 26.74% of a person's height,[4] a ratio found in both men and women and most ethnic groups with only restricted variation, and is useful in anthropology because it offers a basis for a reasonable estimate of a subject's height from an incomplete skeleton.

The femur is categorised as a long bone and comprises a diaphysis (shaft or body) and two epiphyses (extremities) that articulate with adjacent bones in the hip and knee.[3]

Upper part

The upper or proximal extremity (close to the torso) contains the head, neck, the two trochanters and adjacent structures.[3] The upper extremity is the shortest femoral extremity, the lower extremity is the thickest femoral extremity.

The head of the femur, which articulates with the acetabulum of the pelvic bone, comprises two-thirds of a sphere. It has a small groove, or fovea, connected through the round ligament to the sides of the acetabular notch. The head of the femur is connected to the shaft through the neck or collum. The neck is 4–5 cm. long and the diameter is smallest front to back and compressed at its middle. The collum forms an angle with the shaft in about 130 degrees. This angle is highly variant. In the infant it is about 150 degrees and in old age reduced to 120 degrees on average. An abnormal increase in the angle is known as coxa valga and an abnormal reduction is called coxa vara. Both the head and neck of the femur is vastly embedded in the hip musculature and can not be directly palpated. In skinny people with the thigh laterally rotated, the head of the femur can be felt deep as a resistance profound (deep) for the femoral artery.[3]

The transition area between the head and neck is quite rough due to attachment of muscles and the hip joint capsule. Here the two trochanters, greater and lesser trochanter, are found. The greater trochanter is almost box-shaped and is the most lateral prominent of the femur. The highest point of the greater trochanter is located higher than the collum and reaches the midpoint of the hip joint. The greater trochanter can easily be felt. The trochanteric fossa is a deep depression bounded posteriorly by the intertrochanteric crest on the medial surface of the greater trochanter. The lesser trochanter is a cone-shaped extension of the lowest part of the femur neck. The two trochanters are joined by the intertrochanteric crest on the back side and by the intertrochanteric line on the front.[3]

A slight ridge is sometimes seen commencing about the middle of the intertrochanteric crest, and reaching vertically downward for about 5 cm. along the back part of the body: it is called the linea quadrata (or quadrate line).

About the junction of the upper one-third and lower two-thirds on the intertrochanteric crest is the quadrate tubercle located. The size of the tubercle varies and it is not always located on the intertrochanteric crest and that also adjacent areas can be part of the quadrate tubercle, such as the posterior surface of the greater trochanter or the neck of the femur. In a small anatomical study it was shown that the epiphyseal line passes directly through the quadrate tubercle.[5]

Body

The body of the femur (or shaft) is large, thick and almost cylindrical in form. It is a little broader above than in the center, broadest and somewhat flattened from before backward below. It is slightly arched, so as to be convex in front, and concave behind, where it is strengthened by a prominent longitudinal ridge, the linea aspera which diverges proximally and distal as the medial and lateral ridge. Proximally the lateral ridge of the linea aspera becomes the gluteal tuberosity while the medial ridge continues as the pectineal line. Besides the linea aspera the shaft has two other bordes; a lateral and medial border. These three bordes separates the shaft into three surfaces: One anterior, one medial and one lateral. Due to the vast musculature of the thigh the shaft can not be palpated.[3]

The third trochanter is a bony projection occasionally present on the proximal femur near the superior border of the gluteal tuberosity. When present, it is oblong, rounded, or conical in shape and sometimes continuous with the gluteal ridge.[6] A structure of minor importance in humans, the incidence of the third trochanter varies from 17–72% between ethnic groups and it is frequently reported as more common in females than in males.[7]

Lower part

The lower extremity of the femur (or distal extremity) is the thickest femoral extremity, the upper extremity is the shortest femoral extremity. It is somewhat cuboid in form, but its transverse diameter is greater than its antero-posterior (front to back). It consists of two oblong eminences known as the condyles.[3]

Anteriorly, the condyles are slightly prominent and are separated by a smooth shallow articular depression called the patellar surface. Posteriorly, they project considerably and a deep notch, the Intercondylar fossa of femur, is present between them. The lateral condyle is the more prominent and is the broader both in its antero-posterior and transverse diameters. The medial condyle is the longer and, when the femur is held with its body perpendicular, projects to a lower level. When, however, the femur is in its natural oblique position the lower surfaces of the two condyles lie practically in the same horizontal plane. The condyles are not quite parallel with one another; the long axis of the lateral is almost directly antero-posterior, but that of the medial runs backward and medialward. Their opposed surfaces are small, rough, and concave, and form the walls of the intercondyloid fossa. This fossa is limited above by a ridge, the intercondyloid line, and below by the central part of the posterior margin of the patellar surface. The posterior cruciate ligament of the knee joint is attached to the lower and front part of the medial wall of the fossa and the anterior cruciate ligament to an impression on the upper and back part of its lateral wall.[3]

The articular surface of the lower end of the femur occupies the anterior, inferior, and posterior surfaces of the condyles. Its front part is named the patellar surface and articulates with the patella; it presents a median groove which extends downward to the intercondyloid fossa and two convexities, the lateral of which is broader, more prominent, and extends farther upward than the medial.[3]

Each condyle is surmounted by an elevation, the epicondyle. The medial epicondyle is a large convex eminence to which the tibial collateral ligament of the knee-joint is attached. At its upper part is the adductor tubercle and behind it is a rough impression which gives origin to the medial head of the gastrocnemius. The lateral epicondyle which is smaller and less prominent than the medial, gives attachment to the fibular collateral ligament of the knee-joint.[3]

Development

The femur develops from the limb buds as a result of interactions between the ectoderm and the underlying mesoderm, formation occurs roughly around the fourth week of development.[8]

By the sixth week of development, the first hyaline cartilage model of the femur is formed by chondrocytes. Endochondral ossification begins by the end of the embryonic period and primary ossification centers are present in all long bones of the limbs, including the femur, by the 12th week of development. The hindlimb development lags behind forelimb development by 1–2 days.

Function

As the femur is the only bone in the thigh, it serves as an attachment point for all the muscles that exert their force over the hip and knee joints. Some biarticular muscles – which cross two joints, like the gastrocnemius and plantaris muscles – also originate from the femur. In all, 23 individual muscles either originate from or insert onto the femur.

In cross-section, the thigh is divided up into three separate fascial compartments divided by fascia, each containing muscles. These compartments use the femur as an axis, and are separated by tough connective tissue membranes (or septa). Each of these compartments has its own blood and nerve supply, and contains a different group of muscles. These compartments are named the anterior, medial and posterior fascial compartments.

Muscle attachments

Muscle attachments (seen from the front) |  Muscle attachments (seen from the back) |

| Muscle | Direction | Attachment[9] |

| Iliacus muscle | Insertion | Lesser trochanter |

| Psoas major muscle | Insertion | Lesser trochanter |

| Gluteus maximus muscle | Insertion | Gluteal tuberosity |

| Gluteus medius muscle | Insertion | Lateral surface of greater trochanter |

| Gluteus minimus muscle | Insertion | Forefront of greater trochanter |

| Piriformis muscle | Insertion | Superior boundary of greater trochanter |

| Gemellus superior muscle | Insertion | Upper edge of Obturator internus's tendon (indirectly greater trochanter) |

| Obturator internus muscle | Insertion | Medial surface of greater trochanter |

| Gemellus inferior muscle | Insertion | Lower edge of Obturator internus's tendon (indirectly greater trochanter) |

| Quadratus femoris muscle | Insertion | Intertrochanteric crest |

| Obturator externus muscle | Insertion | Trochanteric fossa |

| Pectineus muscle | Insertion | Pectineal line |

| Adductor longus muscle | Insertion | Medial ridge of linea aspera |

| Adductor brevis muscle | Insertion | Medial ridge of linea aspera |

| Adductor magnus muscle | Insertion | Medial ridge of linea aspera and the adductor tubercle |

| Vastus lateralis muscle | Origin | Greater trochanter and lateral ridge of linea aspera |

| Vastus intermedius muscle | Origin | Front and lateral surface of femur |

| Vastus medialis muscle | Origin | Distal part of intertrochanteric line and medial ridge of linea aspera |

| Short head of biceps femoris | Origin | Lateral ridge of linea aspera |

| Popliteus muscle | Origin | Under the lateral epicondyle |

| Articularis genu muscle | Origin | Lower 1/4 of anterior femur deep to vastus intermedius |

| Gastrocnemius muscle | Origin | Behind the adductor tubercle, over the lateral epicondyle and the popliteal facies |

| Plantaris muscle | Origin | Over the lateral condyle |

Clinical significance

Fractures

A femoral fracture that involves the femoral head, femoral neck or the shaft of the femur immediately below the lesser trochanter may be classified as a hip fracture, especially when associated with osteoporosis. Femur fractures can be managed in a pre-hospital setting with the use of a traction splint.

Diversity among animals

-from-the-Genus-pone.0099929.g002.jpg.webp)

In primitive tetrapods, the main points of muscle attachment along the femur are the internal trochanter and third trochanter, and a ridge along the ventral surface of the femoral shaft referred to as the adductor crest. The neck of the femur is generally minimal or absent in the most primitive forms, reflecting a simple attachment to the acetabulum. The greater trochanter was present in the extinct archosaurs, as well as in modern birds and mammals, being associated with the loss of the primitive sprawling gait. The lesser trochanter is a unique development of mammals, which lack both the internal and fourth trochanters. The adductor crest is also often absent in mammals or alternatively reduced to a series of creases along the surface of the bone.[10] Structures analogous to the third trochanter are present in mammals, including some primates.[7]

Some species of whales,[11] snakes, and other non-walking vertebrates have vestigial femurs. In some snakes the protruding end of a pelvic spur, a vestigial pelvis and femur remnant which is not connected to the rest of the skeleton, plays a role in mating. This role in mating is hypothesized to have possibly occurred in Basilosauridae, an extinct family of whales with well-defined femurs, lower legs and feet. Occasionally, the genes that code for longer extremities cause a modern whale to develop miniature legs (atavism).[12]

One of the earliest known vertebrates to have a femur is the eusthenopteron, a prehistoric lobe-finned fish from the Late Devonian period.

Viral metagenomics

A recent study revealed that bone is a much richer source of persistent DNA viruses than earlier perceived. Besides Parvovirus 19 and hepatitis B virus, ten additional ones were discovered, namely several members of the herpes- and polyomavirus families, as well as human papillomavirus 31 and torque teno virus. [13]

Invertebrates

In invertebrate zoology the name femur appears in arthropodology. The usage is not homologous with that of vertebrate anatomy; the term "femur" simply has been adopted by analogy and refers, where applicable, to the most proximal of (usually) the two longest jointed segments of the legs of the arthropoda. The two basal segments preceding the femur are the coxa and trochanter. This convention is not followed in carcinology but it applies in arachnology and entomology. In myriapodology another segment, the prefemur, connects the trochanter and femur.

Additional media

View from behind.

View from behind. View from the front.

View from the front. 3D image

3D image.png.webp) Long bone (femur)

Long bone (femur) Muscles of thigh. Lateral view.

Muscles of thigh. Lateral view. Muscles of thigh. Cross section.

Muscles of thigh. Cross section. Distribution forces of the femur

Distribution forces of the femur

References

- "femora". Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

- "femora". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- Bojsen-Møller, Finn; Simonsen, Erik B.; Tranum-Jensen, Jørgen (2001). Bevægeapparatets anatomi [Anatomy of the Locomotive Apparatus] (in Danish) (12th ed.). pp. 239–241. ISBN 978-87-628-0307-7.

- Feldesman, M.R., J.G. Kleckner, and J.K. Lundy. (November 1990). "The femur/stature ratio and estimates of stature in mid-and late-pleistocene fossil hominids". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 83 (3): 359–372. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330830309. PMID 2252082.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Sunderland S (January 1938). "The Quadrate Tubercle of the Femur". J. Anat. 72 (Pt 2): 309–12. PMC 1252427. PMID 17104699.

- Lozanoff, Scott; Sciulli, Paul W; Schneider, Kim N (December 1985). "Third trochanter incidence and metric trait covariation in the human femur". J Anat. 143: 149–159. PMC 1166433. PMID 3870721.

- Bolanowski, Wojciech; Śmiszkiewicz-Skwarska, Alicja; Polguj, Michał; Jędrzejewski, Kazimierz S (2005). "The occurrence of the third trochanter and its correlation to certain anthropometric parameters of the human femur" (PDF). Folia Morphol. 64 (3): 168–175. PMID 16228951.

- Gilbert, Scott F. "Developmental Biology". 9th ed., 2010

- Bojsen-Møller, Finn; Simonsen, Erik B.; Tranum-Jensen, Jørgen (2001). Bevægeapparatets anatomi [Anatomy of the Locomotive Apparatus] (in Danish) (12th ed.). pp. 364–367. ISBN 978-87-628-0307-7.

- Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 204–205. ISBN 978-0-03-910284-5.

- Struthers, John (January 1881). "The Bones, Articulations, and Muscles of the Rudimentary Hind-Limb of the Greenland Right-Whale (Balaena mysticetus)". Journal of Anatomy and Physiology. 15 (Pt 2): i1–176. PMC 1310010. PMID 17231384.

- Bejder, Lars; Hall, Brian K. (2002). "Limbs in whales and limblessness in other vertebrates: mechanisms of evolutionary and developmental transformation and loss". Evolution & Development. 4 (6): 445–458. doi:10.1046/j.1525-142X.2002.02033.x. PMID 12492145. S2CID 8448387.

- Toppinen, Mari; Pratas, Diogo; Väisänen, Elina; Söderlund-Venermo, Maria; Hedman, Klaus; Perdomo, Maria F.; Sajantila, Antti (2020). "The landscape of persistent human DNA viruses in femoral bone". Forensic Science International: Genetics. 48: 102353. doi:10.1016/j.fsigen.2020.102353. hdl:10138/332288. PMID 32668397. S2CID 220582800.