Patella

The patella, also known as the kneecap, is a flat, rounded triangular bone which articulates with the femur (thigh bone) and covers and protects the anterior articular surface of the knee joint. The patella is found in many tetrapods, such as mice, cats, birds and dogs, but not in whales, or most reptiles.

| Patella | |

|---|---|

Right knee | |

| Details | |

| Pronunciation | /pəˈtɛlə/ |

| Origins | present at the joint of femur and tibia fibula |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | patella |

| MeSH | D010329 |

| TA98 | A02.5.05.001 |

| TA2 | 1390 |

| FMA | 24485 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

In humans, the patella is the largest sesamoid bone (i.e., embedded within a tendon or a muscle) in the body. Babies are born with a patella of soft cartilage which begins to ossify into bone at about four years of age.

Structure

The patella is a sesamoid bone roughly triangular in shape, with the apex of the patella facing downwards. The apex is the most inferior (lowest) part of the patella. It is pointed in shape, and gives attachment to the patellar ligament.

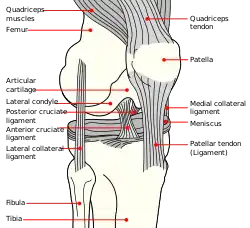

The front and back surfaces are joined by a thin margin and towards centre by a thicker margin.[1] The tendon of the quadriceps femoris muscle attaches to the base of the patella.,[1] with the vastus intermedius muscle attaching to the base itself, and the vastus lateralis and vastus medialis are attached to outer lateral and medial borders of patella respectively.

The upper third of the front of the patella is coarse, flattened, and rough, and serves for the attachment of the tendon of the quadriceps and often has exostoses. The middle third has numerous vascular canaliculi. The lower third culminates in the apex which serves as the origin of the patellar ligament.[1] The posterior surface is divided into two parts.[1]

Human left patella from the front

Human left patella from the front Human left patella from behind

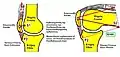

Human left patella from behind Flexion and extension of knee

Flexion and extension of knee

The upper three-quarters of the patella articulates with the femur and is subdivided into a medial and a lateral facet by a vertical ledge which varies in shape.

In the adult the articular surface is about 12 cm2 (1.9 sq in) and covered by cartilage, which can reach a maximal thickness of 6 mm (0.24 in) in the centre at about 30 years of age. Owing to the great stress on the patellofemoral joint during resisted knee flexion, the articular cartilage of the patella is among the thickest in the human body.

The lower part of the posterior surface has vascular canaliculi filled and is filled by fatty tissue, the infrapatellar fat pad.

Variation

Emarginations (i.e. patella emarginata, a "missing piece") are common laterally on the proximal edge.[1] Bipartite patellas are the result of an ossification of a second cartilaginous layer at the location of an emargination. Previously, bipartite patellas were explained as the failure of several ossification centres to fuse, but this idea has been rejected. Partite patellas occur almost exclusively in men. Tripartite and even multipartite patellas occur.

The upper three-quarters of the patella articulates with the femur and is subdivided into a medial and a lateral facet by a vertical ledge which varies in shape. Four main types of articular surface can be distinguished:

- Most commonly the medial articular surface is smaller than the lateral.

- Sometimes both articular surfaces are virtually equal in size.

- Occasionally, the medial surface is hypoplastic or

- the central ledge is only indicated.

Development

In the patella an ossification centre develops at the age of 3–6 years.[1] The patella originates from two centres of ossification which unite when fully formed.

Function

The primary functional role of the patella is knee extension. The patella increases the leverage that the quadriceps tendon can exert on the femur by increasing the angle at which it acts.

The patella is attached to the tendon of the quadriceps femoris muscle, which contracts to extend/straighten the knee. The patella is stabilized by the insertion of the horizontal fibres of vastus medialis and by the prominence of the lateral femoral condyle, which discourages lateral dislocation during flexion. The retinacular fibres of the patella also stabilize it during exercise.

Clinical significance

Dislocation

Patellar dislocations occur with significant regularity, particularly in young female athletes.[2] It involves the patella sliding out of its position on the knee, most often laterally, and may be associated with extremely intense pain and swelling.[3] The patella can be tracked back into the groove with an extension of the knee, and therefore sometimes returns into the proper position on its own.[3]

Vertical alignment

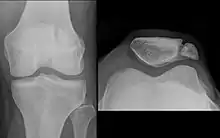

A patella alta is a high-riding (superiorly aligned) patella. An attenuated patella alta is an unusually small patella that develops out of and above the joint.

A patella baja is a low-riding patella. A long-standing patella baja may result in extensor dysfunction.[5]

The Insall-Salvati ratio helps to indicate patella baja on lateral X-rays, and is calculated as the patellar tendon length divided by the patellar bone length. An Insall-Salvati ratio of < 0.8 indicates patella baja.[6]

Fracture

The kneecap is prone to injury because of its particularly exposed location, and fractures of the patella commonly occur as a consequence of direct trauma onto the knee. These fractures usually cause swelling and pain in the region, bleeding into the joint (hemarthrosis), and an inability to extend the knee. Patella fractures are usually treated with surgery, unless the damage is minimal and the extensor mechanism is intact.[7]

Exostosis

An exostosis is the formation of new bone onto a bone, as a result of excess calcium formation. This can be the cause of chronic pain when formed on the patella.

In animals

The patella is found in placental mammals and birds; most marsupials have only rudimentary, non-ossified patellae although a few species possess a bony patella.[8] A patella is also present in the living monotremes, the platypus and the echidna. In more primitive tetrapods, including living amphibians and most reptiles (except some Lepidosaurs), the muscle tendons from the upper leg are attached directly to the tibia, and a patella is not present.[9] In 2017 it was discovered that frogs have kneecaps, contrary to what was thought. This raises the possibility that the kneecap arose 350 million years ago when tetrapods first appeared, but that it disappeared in some animals.[10][11]

Etymology

The word patella originated in the late 17th century from the diminutive form of Latin patina or patena or paten, meaning shallow dish.[12][13]

See also

- Patellar reflex

- Knee pain

- Osteoarthritis

- Lateral retinaculum

- Lateral release

References

- Platzer, Werner (2004). Color Atlas of Human Anatomy, Vol. 1: Locomotor System (5th ed.). Thieme. p. 194. ISBN 3-13-533305-1.

- Palmu, S.; Kallio, P.E.; Donell, S.T.; Helenius, I.; Nietosvaara, Y. (2008). "Acute patellar dislocation in children and adolescents: A randomized clinical trial". Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 90 (3): 463–470. doi:10.2106/JBJS.G.00072. PMID 18310694.

- Dath, R.; Chakravarthy, J.; Porter, K.M. (2006). "Patella Dislocations". Trauma. 8: 5–11. doi:10.1191/1460408606ta353ra. S2CID 208269986.

- Melloni, Pietro; Veintemillas, Maite; Marin, Anna; Valls, Rafael (2013). "Imaging Patellar Complications After Knee Arthroplasty". Arthroplasty - Update. doi:10.5772/53666. ISBN 978-953-51-0995-2. (CC-BY-3.0)

- Yuranga Weerakkody and Frank Gaillard. "Patella baja". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 2018-01-16.

- Douglas Dennis (2017-02-25). "TKA in Patella Baja (Infera)". Orthobullets. Retrieved 2019-02-08.

- Bentley, G (2014). European Surgical Orthopaedics and Traumatology: The EFORT Textbook. Springer. pp. 2766–2784. ISBN 978-3642347450.

- Herzmark MH (1938). "The Evolution of the Knee Joint" (PDF). J Bone Joint Surg Am. 20 (1): 77–84. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-17. Retrieved 2007-11-17.

- Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. p. 205. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

- "Frogs have hidden, ancient kneecaps". New Scientist. Jul 15, 2017.

- Virginia Abdala; et al. (Jul 2017). "On the presence of the patella in frogs". The Anatomical Record. 300 (10): 1747–1755. doi:10.1002/ar.23629. PMID 28667673.

- New Shorter Oxford

- "patella - Origin and meaning of patella by Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com.