First Macedonian War

The First Macedonian War (214–205 BC) was fought by Rome, allied (after 211 BC) with the Aetolian League and Attalus I of Pergamon, against Philip V of Macedon, contemporaneously with the Second Punic War (218–201 BC) against Carthage. There were no decisive engagements, and the war ended in a stalemate.

| First Macedonian War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Macedonian Wars and the Second Punic War | |||||||

The Mediterranean in 218 BC | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Roman Republic Kingdom of Illyria Aetolian League Kingdom of Pergamon Kingdom of Sparta Elis Messenia |

Macedonia Achaean League | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Marcus Valerius Laevinus Scerdilaidas Attalus I Machanidas † |

Philip V of Macedon Philopoemen Demetrius of Pharus † | ||||||

During the war, Macedon attempted to gain control over parts of Illyria and Greece, but without success. It is commonly thought that these skirmishes in the east prevented Macedon from aiding the Carthaginian general Hannibal in the war with Rome. The Peace of Phoenice (205 BC) formally ended the war.

Demetrius urges war against Rome

Rome's preoccupation with its war against Carthage provided an opportunity for Philip V of Macedon to attempt to extend his power westward. According to the ancient Greek historian Polybius, an important factor in Philip's decision to take advantage of this opportunity was the influence of Demetrius of Pharos.

After the First Illyrian War (229–228 BC) the Romans had made Demetrius ruler of most of coastal Illyria.[1] In the decade after the war he turned against the Romans attacking their allies in Illyria and raiding their trade vessels. In 219 BC, during the Second Illyrian War he was defeated by the Romans and fled to the court of king Philip.[2]

Involved in a war with the Aetolians, Philip learned of the victory of Hannibal over the Romans, at Lake Trasimene in June 217 BC. Philip at first showed the letter only to Demetrius. Perhaps seeing a chance to recover his kingdom, Demetrius immediately advised the young king to make peace with the Aetolians and turn his attentions toward Illyria and Italy. Polybius quotes Demetrius as saying:

For Greece is already entirely obedient to you, and will remain so: the Achaeans from genuine affection; the Aetolians from the terror which their disasters in the present war have inspired them. Italy, and your crossing into it, is the first step in the acquirement of universal empire, to which no one has a better claim than yourself. And now is the moment to act when the Romans have suffered a reverse.[3]

Philip was easily persuaded.[4]

Philip makes peace with Aetolia

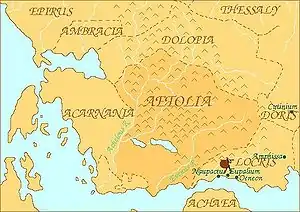

Philip at once began negotiations with the Aetolians. At a conference on the coast near Naupactus, Philip met the Aetolian leaders and a peace treaty was concluded.[5] Polybius quotes the Aetolian Agelaus of Naupactus as having given the following speech[6] in favor of peace:

The best thing of all is that the Greeks should not go to war with each other at all, but give the gods hearty thanks if by all speaking with one voice, and joining hands like people crossing a stream, they may be able to repel the attacks of barbarians and save themselves and their cities. But if this is altogether impossible, in the present juncture at least we ought to be unanimous and on our guard, when we see the bloated armaments and the vast proportions assumed by the war in the west. For even now it is evident to any one who pays even a moderate attention to public affairs, that whether the Carthaginians conquer the Romans, or the Romans the Carthaginians, it is in every way improbable that the victors will remain contented with the empire of Sicily and Italy. They will move forward: and will extend their forces and their designs farther than we could wish. Wherefore, I beseech you all to be on your guard against the danger of the crisis, and above all you, O King. You will do this, if you abandon the policy of weakening the Greeks, and thus rendering them an easy prey to the invader; and consult on the contrary for their good as you would for your own person, and have a care for all parts of Greece alike, as part and parcel of your own domains. If you act in this spirit, the Greeks will be your warm friends and faithful coadjutors in all your undertakings; while foreigners will be less ready to form designs against you, seeing with dismay the firm loyalty of the Greeks. If you are eager for action, turn your eyes to the west, and let your thoughts dwell upon the wars in Italy. Wait with coolness the turn of events there, and seize the opportunity to strike for universal dominion. Nor is the present crisis unfavourable for such a hope. But I intreat of you to postpone your controversies and wars with the Greeks to a time of greater tranquillity; and make it your supreme aim to retain the power of making peace or war with them at your own will. For if once you allow the clouds now gathering in the west to settle upon Greece, I fear exceedingly that the power of making peace or war, and in a word all these games which we are now playing against each other, will be so completely knocked out of the hands of us all, that we shall be praying heaven to grant us only this power of making war or peace with each other at our own will and pleasure, and of settling our own disputes.[7]

Philip builds a fleet

Philip spent the winter of 217–216 BC building a fleet of 100 warships and training men to row them and, according to Polybius, it was a practice that "hardly any Macedonian king had ever done before".[8] Macedon probably lacked the resources to build and maintain the kind of fleet necessary to match the Romans.[9] Polybius says that Philip had no "hope of fighting the Romans at sea",[8] perhaps referring to a lack of experience and training.

At any rate, Philip chose to build lembi. These were the small fast galleys used by the Illyrians. They had a single bank of oars and were able to carry 50 soldiers in addition to the rowers.[10] With these, Philip could hope to avoid or evade the Roman fleet, preoccupied as he hoped it would be with Hannibal, and based as it was at Lilybaeum in western Sicily.[8]

Philip had in the meantime expanded his territories west along the Apsus and Genusus river valleys, right up to the borders of Illyria.[11] Philip's plan was, it seems, to first take the Illyrian coasts, conquer the area between the coasts and Macedon, and use the new land link to provide a rapid route for reinforcements across the narrow straits to Italy.[12]

At the beginning of summer, Philip and his fleet left Macedon, sailed through the Euripus Strait, between the island of Euboea and Boeotia on the Greek mainland, and then rounded Cape Malea, before dropping anchor off the Islands of Cephalenia and Leucas, to await word of the location of the Roman fleet. Informed that it was still at Lilybaeum, he sailed north to Apollonia in Illyria.

However, as the Macedonian fleet neared the island of Sazan, Philip heard a report that some Roman quinqueremes had been seen headed for Apollonia. Convinced that the entire Roman fleet was sailing to apprehend him, Philip ordered an immediate return to Cephalenia. Polybius speaks of "panic" and "disorder" to describe the fleet's hasty retreat and says that, in fact, the Romans had sent only a squadron of ten ships and that because of "inconsiderate alarm", Philip had missed his best chance to achieve his aims in Illyria, returning to Macedon, "without loss indeed, but with considerable dishonour".[13]

Philip allies with Carthage

After hearing of Rome's disastrous defeat at the hands of Hannibal at Cannae in 216 BC, Philip sent ambassadors to Hannibal's camp in Italy to negotiate an alliance. There they concluded in the summer of 215 BC a treaty, the text of which is given by Polybius. In it they pledge, in general terms, mutual support and defense and to be enemies to each other's enemies (excepting current allies). Specifically, they promised support against Rome and that Hannibal shall have the right to make peace with Rome, but that any peace would include Philip and that Rome would be forced to relinquish control of Corcyra, Apollonia, Epidamnus, Pharos, Dimale, Parthini, and Atintania and "to restore to Demetrius of Pharos all those of his friends now in the dominion of Rome."[14]

The treaty as set down by Polybius makes no mention of an invasion of Italy by Philip, the debacle at Sazan perhaps having soured Philip on such a venture,[15] something which in any case Hannibal may not have desired.[16]

On their way back to Macedon, Philip's emissaries, along with emissaries from Hannibal, were captured by Publius Valerius Flaccus, commander of the Roman fleet patrolling the southern Apulian coast. A letter from Hannibal to Philip and the terms of their agreement, were discovered.[17]

Philip's alliance with Carthage caused immediate dismay in Rome, hard-pressed as they already were. An additional twenty-five warships were at once outfitted and sent to join Flaccus' fleet of twenty-five warships already at Tarentum, with orders to guard the Italian Adriatic coast, to try to determine Philip's intent and, if necessary, cross over to Macedonia, keeping Philip confined there.[18]

War breaks out in Illyria

In the late summer of 214 BC, Philip again attempted an Illyrian invasion by sea, with a fleet of 120 lembi. He captured Oricum which was lightly defended, and sailing up the Aous (modern Vjosë) river he besieged Apollonia.[19]

Meanwhile, the Romans had moved the fleet from Tarentum to Brundisium to continue the watch on the movements of Philip and a legion had been sent in support, all under the command of the Roman propraetor Marcus Valerius Laevinus.[20] Upon receiving word from Oricum of events in Illyria, Laevinus crossed over with his fleet and army. Landing at Oricum, Laevinus was able to retake the town with little fighting.

In the account given by Livy,[21] Laevinus, hearing that Apollonia was under siege, sent 2000 men under the command of Quintus Naevius Crista, to the mouth of the river. Avoiding Philip's army, Crista was able to enter the city by night unobserved. The following night, catching Philip's forces by surprise, he attacked and routed their camp. Escaping to his ships in the river, Philip made his way over the mountains and back to Macedonia, having burned his fleet and leaving behind many thousands of his men that had died or been taken prisoner, along with all of his armies' possessions. Meanwhile, Laevinus and his fleet wintered at Oricum.

Twice thwarted in his attempts at invasion of Illyria by sea, and now constrained by Laevinus' fleet in the Adriatic, Philip spent the next two years (213–212 BC) making advances in Illyria by land. Keeping clear of the coast, he took Dassaretis, Atintani and Parthini, and the town of Dimale.[22]

He was finally able to gain access to the Adriatic by capturing Lissus and its seemingly impregnable citadel, after which the surrounding territories surrendered.[23] Perhaps the capture of Lissus rekindled in Philip hopes of an Italian invasion.[24] However, the loss of his fleet meant that Philip would now be dependent on Carthage for passage to and from Italy, making the prospect of invasion considerably less appealing.

Rome seeks allies in Greece

Desiring to prevent Philip from aiding Carthage in Italy and elsewhere, Rome sought out allies in Greece.

Laevinus had begun exploring the possibility of an alliance with the Aetolian League as early as 212 BC.[25] The war weary Aetolians had made peace with Philip at Naupactus in 217 BC. However, five years later the war faction was on the ascend and the Aetolians were once again considering taking up arms against their traditional enemy, Macedonia.

In 211 BC, an Aetolian assembly was convened for discussions with Rome. Laevinus pointed out the recent capture of Syracuse and Capua in the war against Carthage as evidence of Rome's rising fortunes and offered to ally with them against the Macedonians. A treaty was signed whereby the Aetolians would conduct operations on land, the Romans at sea and Rome would keep any slaves and other booty taken and Aetolia would receive control of any territory acquired. Another provision of the treaty allowed for the inclusion of certain allies of the League: Elis, Sparta, Messenia and Attalus I of Pergamon, as well as two Roman clients, the Illyrians Pleuratus and Scerdilaidas.[26]

Campaign in Greece

Later that summer, Laevinus seized the main town of Zacynthus, except for its citadel, the Acarnanian town of Oeniadae and the island of Nasos, which he handed over to the Aetolians. He then withdrew his fleet to Corcyra for the winter.[27]

Upon hearing of the Roman alliance with Aetolia, Philip's first action was to secure his northern borders. He conducted raids in Illyria at Oricum and Apollonia and seized the frontier town of Sintia in Dardania or perhaps Paionia. He then marched rapidly south through Pelagonia, Lyncestis and Bottiaea and on to Tempe which he garrisoned with 4,000 men. He turned north again into Thrace, attacking the Maedi and their chief city Iamphorynna before returning to Macedon.

No sooner had Philip arrived there when he received an urgent plea for help from his ally the Acarnanians. Scopas the Aetolian strategos (general) had mobilized the Aetolian army and was preparing to invade Acarnania. Desperate and overmatched, but determined to resist, the Acarnanians sent their women, children and old men to seek refuge in Epirus and the rest marched to the frontier, having sworn an oath to fight to the death, "invoking a terrible curse" upon any who were forsworn. Hearing of the Acarnanians' grim determination, the Aetolians hesitated then, learning of Philip's approach, finally abandoned their invasion, after which Philip retired to Pella for the winter.[28]

In the spring of 210 BC, Laevinus again sailed from Corcyra with his fleet and, together with the Aetolians, captured Phocian Anticyra. Rome enslaved the inhabitants and Aetolia took possession of the town.[29]

Although there was some fear of Rome and concern with her methods,[30] the coalition arrayed against Philip continued to grow. As allowed for by the treaty, Pergamon, Elis and Messenia, followed by Sparta, all agreed to join the alliance against Macedon.[31] The Roman fleet, together with the Pergamene fleet, controlled the sea, and Macedon and her allies were threatened on land by the rest of the coalition. The Roman strategy of encumbering Philip with a war among Greeks in Greece was succeeding, so much so that when Laevinus went to Rome to take up his consulship, he was able to report that the legion deployed against Philip could be safely withdrawn.[32]

However, the Eleans, Messenians and Spartans remained passive throughout 210 BC and Philip continued to make advances. He invested and took Echinus, using extensive siegeworks, having beaten back an attempt to relieve the town by the Aetolian strategos Dorimachus and the Roman fleet, now commanded by the proconsul Publius Sulpicius Galba.[33] Moving west, Philip probably also took Phalara the port city of Lamia, in the Maliac Gulf. Sulpicius and Dorimachus took Aegina, an island in the Saronic Gulf, which the Aetolians sold to Attalus, the Pergamene king, for thirty talents, and which he was to use as his base of operations against Macedon in the Aegean Sea.

In the spring of 209 BC, Philip received requests for help from his ally the Achaean League in the Peloponnesus who were being attacked by Sparta and the Aetolians. He also heard that Attalus had been elected one of the two supreme commanders of the Aetolian League, as well as rumors that he intended to crossover the Aegean from Asia Minor.[34] Philip marched south into Greece. At Lamia he was met by an Aetolian force, supported by Roman and Pergamene auxiliaries, under the command of Attalus' colleague as strategos, the Aetolian Pyrrhias. Philip won two battles at Lamia, inflicting heavy casualties on Pyrrhias' troops. The Aetolians and their allies were forced to retreat inside the city walls, where they remained, unwilling to give battle.

Attempt at peace fails

From Lamia, Philip went to Phalara where he met representatives from the neutral states of Egypt, Rhodes, Athens and Chios who were trying to end the war. As trading states, the war was likely hurting trade;[35] Livy says that they were concerned "not so much for the Aetolians, who were more warlike than the rest of the Greeks, as for the liberty of Greece, which would be seriously endangered if Philip and his kingdom took an active part in Greek politics." With them was Amynandor of Athamania, representing the Aetolians. A truce of thirty days and a peace conference at Achaea were arranged.

Philip marched to Chalcis in Euboea, which he garrisoned to block Attalus' landing there, then continued on to Aegium for the conference. The conference was interrupted by a report that Attalus had arrived at Aegina and the Roman fleet was at Naupactus. The Aetolian representatives, emboldened by these events, at once demanded that Philip return Pylos to the Messenians, Atintania to Rome and the Ardiaei to Scerdilaidas and Pleuratus. "Indignant", Philip quit the negotiations telling the assembly that they "might bear him witness that whilst he was seeking a basis for peace, the other side were determined to find a pretext for war".[36]

Hostilities resume

From Naupactus, Sulpicius sailed east to Corinth and Sicyon, conducting raids there. Philip, with his cavalry, caught the Romans ashore and was able to drive them back to their ships, with the Romans returning to Naupactus.

Philip then joined Cycliadas, the Achaean general, near Dyme for a joint attack on the city of Elis, the main Aetolian base of operations against Achaea.[37] However, Sulpicius had sailed into Cyllene and reinforced Elis with a force of 4,000 Roman troops. Leading a charge, Philip was thrown from his horse. Fighting on foot, Philip became the object of a fierce battle, finally escaping on another horse. The next day, Philip captured the stronghold of Phyricus, taking 4,000 prisoners and 20,000 animals. Hearing news of Illyrian incursions in the north, Philip abandoned Aetolia and returned to Demetrias in Thessaly.[38]

Meanwhile, Sulpicius sailed round into the Aegean and joined Attalus on Aegina for the winter.[39] In 208 BC, the combined fleet of thirty-five Pergamene and twenty-five Roman ships failed to take Lemnos, but occupied and plundered the countryside of the island of Peparethos (Skopelos), both Macedonian possessions.[40]

Attalus and Sulpicius then attended a meeting in Heraclea Trachinia of the Council of the Aetolians, which included representatives from Egypt and Rhodes, who were continuing to try to arrange a peace. Learning of the conference and the presence of Attalus, Philip marched rapidly south in an attempt to break up the conference and catch the enemy leaders, but arrived too late.[41]

Surrounded by foes, Philip was forced to adopt a defensive policy.[42] He distributed his commanders and forces and set up a system of beacon fires at various high places to communicate instantly any enemy movements.

After leaving Heraclea, Attalus and Sulpicius sacked both Oreus on the northern coast of Euboea, and Opus, the chief city of eastern Locris.[43] The spoils from Oreus had been reserved for Sulpicius, who returned there, while Attalus stayed to collect the spoils from Opus. However, with their forces divided, Philip, alerted by signal fire, attacked and took Opus. Attalus, caught by surprise, was barely able to escape to his ships.

The war ends

Although Philip considered Attalus' escape a bitter defeat,[44] it proved to be the turning point of the war. Attalus was forced to return to Pergamon, when he learned at Opus that, perhaps at the urging of Philip, Prusias I, king of Bithynia and related to Philip by marriage, was moving against Pergamon. Sulpicius returned to Aegina, so free from the pressure of the combined Roman and Pergamene fleets, Philip was able to resume the offensive against the Aetolians. He captured Thronium, followed by the towns of Tithronium and Drymaea north of the Cephisus, controlling all of Epicnemidian Locris,[45] and took back control of Oreus.[46]

The neutral trading powers were still trying to arrange a peace and, at Elateia, Philip met with the same would-be peacemakers from Egypt and Rhodes who had been at the previous meeting in Heraclea, and again in the spring of 207 BC, but to no avail.[47] Representatives of Egypt, Rhodes, Byzantium, Chios, Mytilene and perhaps Athens also met again with the Aetolians that spring.[48] The war was going Philip's way, but the Aetolians, although now abandoned by both Pergamon and Rome, were not yet ready to make peace on Philip's terms. However, after another season of fighting, they finally relented. In 206 BC, and without Rome's consent, the Aetolians sued for a separate peace on conditions imposed by Philip.

The following spring[49] the Romans sent the censor Publius Sempronius Tuditanus with 35 ships and 11,000 men to Dyrrachium in Illyria, where he incited the Parthini to revolt and laid siege to Dimale. However, when Philip arrived, Sempronius broke off the siege and withdrew inside the walls of Apollonia. Sempronius tried unsuccessfully to entice the Aetolians to break their peace with Philip. With no more allies in Greece, but having achieved their objective of preventing Philip from aiding Hannibal, the Romans were ready to make peace. A treaty was drawn up at Phoenice in 205 BC, the so-called "Peace of Phoenice," which formally ended the First Macedonian War.[50]

See also

- Military history of Greece

Notes

- Polybius, 2.11.

- Polybius, 3.16, 3.18–19, 4.66.

- Polybius, 5.101.

- Polybius, 5.102.

- Polybius, 5.103–-105.

- Polybius, 5.103.

- Polybius, 5.104. According to Walbank, p. 66, note 5, this speech, "nonwithstanding rhetorical elements … bears the mark of a true version based on contemporary record."

- Polybius, 5.109.

- Walbank, p. 69; Polybius, 5.1, 5.95, 5.108.

- Wilkes, p. 157; Polybius, 2.3.

- Polybius, 5.108.

- Walbank, p. 69.

- Polybius, 5.110.

- Polybius, 7.9.

- According to Walbank, p. 71, note 1, the version of the treaty described in Livy, 23.33.9–12 which mention an Italian invasion by Philip, "are worthless annalistic fabrications".

- Walbank, p. 69, note 3.

- Livy, 23.34.

- Livy, 23.38. Livy says that 20 ships were outfitted and, along with the five ships that transported the agents to Rome, were sent to join Flaccus' fleet of 25 ships. In the same passage he says that 30 ships left Ostia for Tarentum and talks about a combined fleet of 55. Walbank, p. 75, note 2, says that the 55 number given by Livy is a mistake, citing "Holleaux, 187, n. 1."

- Walbank, p. 75; Livy, 24.40.

- Livy, 24.10–11, 20.

- Livy, 24.40. Livy's account is suspect, see Walbank, p. 76, note 1.

- Eckstein, Arthur M. (2008). Rome Enters the Greek East From Anarchy to Hierarchy in the Hellenistic Mediterranean, 230–170 BC. Blackwell Publishing. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-4051-6072-8.

- Polybius, 8.15–16.

- Livy, 24.13, 25.23.

- Walbank, p. 82; Livy, 25.30, 26.24.

- Livy, 26.40. According to Walbank, p. 84, note 2, "Livy accidentally omits Messenia and erroneously describes Pleuratus as king of Thrace."

- Livy, 26.24.

- Livy, 26.25; Polybius, 9.40.

- Livy, 26.26; Polybius, 9.39. Livy says that Anticyra was Locrian, but modern scholars disagree, see Walbank, p. 87, note 2.

- Polybius, 9.37–39, 10.15.

- Polybius, 9,30.

- Livy, 26.28.

- Polybius, 9.41–42.

- Livy, 27.29.

- Walbank, p. 89–90.

- Livy, 27.30.

- Livy, 27.31.

- Livy, 27.32.

- Livy, 27.33.

- Livy, 28.5.

- Polybius, 10.42; Livy, 28.5.

- Polybius, 10.41; Livy, 28.5.

- Livy, 28.6.

- Polybius, 11.7; Livy, 28.7.

- Livy, 28.7; Walbank, p. 96.

- Livy, 28.8.

- Livy, 28.7.

- Polybius, 11.4.

- According to Walbank, p. 102, note 2, Livy, 29.12 "is spoilt by annalistic contamination, which, in the interests of Roman policy, tries to run the Aetolian peace and the return of the Romans as closely together as possible".

- Livy, 29.12.

References

| Library resources about First Macedonian War |

- Hansen, Esther V., The Attalids of Pergamon, Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press; London: Cornell University Press Ltd (1971). ISBN 0-8014-0615-3.

- Kleu, Michael. Die Seepolitik Philipps V. von Makedonien. Bochum, Verlag Dr. Dieter Winkler, 2015.

- Livy, From the Founding of the City, Rev. Canon Roberts (translator), Ernest Rhys (Ed.); (1905) London: J. M. Dent & Sons, Ltd.

- Polybius, Histories, Evelyn S. Shuckburgh (translator); London, New York. Macmillan (1889); Reprint Bloomington (1962).

- Walbank, F. W. (1940), Philip V of Macedon.

- Wilkes, John, The Illyrians, Blackwell Publishers (December 1, 1995). ISBN 0-631-19807-5.