Food

Food is any substance consumed to provide nutritional support for an organism. Food is usually of plant, animal, or fungal origin, and contains essential nutrients, such as carbohydrates, fats, proteins, vitamins, or minerals. The substance is ingested by an organism and assimilated by the organism's cells to provide energy, maintain life, or stimulate growth. Different species of animals have different feeding behaviours that satisfy the needs of their unique metabolisms, often evolved to fill a specific ecological niche within specific geographical contexts.

Omnivorous humans are highly adaptable and have adapted to obtain food in many different ecosystems. Historically, humans secured food through two main methods: hunting and gathering and agriculture. As agricultural technologies increased, humans settled into agriculture lifestyles with diets shaped by the agriculture opportunities in their geography. Geographic and cultural differences has led to creation of numerous cuisines and culinary arts, including a wide array of ingredients, herbs, spices, techniques, and dishes. As cultures have mixed through forces like international trade and globalization, ingredients have become more widely available beyond their geographic and cultural origins, creating a cosmopolitan exchange of different food traditions and practices.

Today, the majority of the food energy required by the ever-increasing population of the world is supplied by the industrial food industry, which produces food with intensive agriculture and distributes it through complex food processing and food distribution systems. This system of conventional agriculture relies heavily on fossil fuels, which means that the food and agricultural system is one of the major contributors to climate change, accountable for as much as 37% of total greenhouse gas emissions.[1] Addressing the carbon intensity of the food system and food waste are important mitigation measures in the global response to climate change.

The food system has significant impacts on a wide range of other social and political issues including: sustainability, biological diversity, economics, population growth, water supply, and access to food. The right to food is a human right derived from the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), recognizing the "right to an adequate standard of living, including adequate food", as well as the "fundamental right to be free from hunger". Because of these fundamental rights, food security is often a priority international policy activity; for example Sustainable Development Goal 2 "Zero hunger" is meant to eliminate hunger by 2030. Food safety and food security are monitored by international agencies like the International Association for Food Protection, World Resources Institute, World Food Programme, Food and Agriculture Organization, and International Food Information Council, and are often subject to national regulation by institutions, like the Food and Drug Administration in the United States.

Definition and classification

Food is any substance consumed to provide nutritional support and energy to an organism.[2][3] It can be raw, processed or formulated and is consumed orally by animals for growth, health or pleasure. Food is mainly composed of water, lipids, proteins and carbohydrates. Minerals (e.g. salts) and organic substances (e.g. vitamins) can also be found in food.[4] Plants, algae and some microorganisms use photosynthesis to make their own food molecules.[5] Water is found in many foods and has been defined as a food by itself.[6] Water and fiber have low energy densities, or calories, while fat is the most energy dense component.[3] Some inorganic (non-food) elements are also essential for plant and animal functioning.[7]

Human food can be classified in various ways, either by related content or by how the food is processed.[8] The number and composition of food groups can vary. Most systems include four basic groups that describe their origin and relative nutritional function: Vegetables and Fruit, Cereals and Bread, Dairy, and Meat.[9] Studies that look into diet quality often group food into whole grains/cereals, refined grains/cereals, vegetables, fruits, nuts, legumes, eggs, dairy products, fish, red meat, processed meat, and sugar-sweetened beverages.[10][11][12] The Food and Agriculture Organization and World Health Organization use a system with nineteen food classifications: cereals, roots, pulses and nuts, milk, eggs, fish and shellfish, meat, insects, vegetables, fruits, fats and oils, sweets and sugars, spices and condiments, beverages, foods for nutritional uses, food additives, composite dishes and savoury snacks.[13]

Food sources

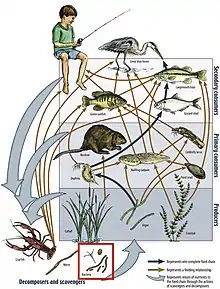

In a given ecosystem, food forms a web of interlocking chains with primary producers at the bottom and apex predators at the top.[14] Other aspects of the web include detrovores (that eat detritis) and decomposers (that break down dead organisms).[14] Primary producers include algae, plants, bacteria and protists that acquire their energy from sunlight.[15] Primary consumers are the herbivores that consume the pants and secondary consumers are the carnivores that consume those herbivores. Some organisms, including most mammals and birds, diets consist of both animals and plants and they are considered omnivores.[16] The chain ends with the apex predators, the animals that have no known predators in its ecosystem.[17] Humans are often considered apex predators.[18]

Humans are omnivores finding sustenance in vegetables, fruits, cooked meat, milk, eggs, mushrooms and seaweed.[16] Cereal grain is a staple food that provides more food energy worldwide than any other type of crop.[19] Corn (maize), wheat, and rice account for 87% of all grain production worldwide.[20][21][22] Just over half of the worlds crops are used to feed humans (55 percent), with 36 percent grown as animal feed and 9 percent for biofuels.[23] Fungi and bacteria are also used in the preparation of fermented foods like bread, wine, cheese and yogurt.[24]

Sunlight

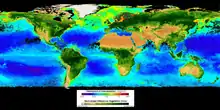

Photosynthesis is the ultimate source of energy and food for nearly all life on earth.[25] It is the main food source for plants, algae and certain bacteria.[26] Without this all organisms which depend on these organisms further up the food chain would be unable to exist, from coral to lions.[27] Energy from the sun is absorbed and used to transform water and carbon dioxide in the air or soil into oxygen and glucose. The oxygen is then released and the glucose stored as an energy reserve.[28]

Plants

.jpg.webp)

Plants as a food source are often divided into seeds, fruits, vegetables, legumes, grains and nuts.[29] Where plants fall within these categories can vary with botanically described fruits such as the tomato, squash, pepper and eggplant or seeds like peas commonly considered vegetables.[30] Food is a fruit if the part eaten is derived from the reproductive tissue, so seeds, nuts and grains are technically fruit.[31][32] From a culinary perspective fruits are generally considered the remains of botanically described fruits after grains, nuts, seeds and fruits used as vegetables are removed.[33] Grains can be defined as seeds that humans eat or harvest, with cereal grains (oats, wheat, rice, corn, barley, rye, sorghum and millet) belonging to the Poaceae (grass) family[34] and pulses coming from the Fabaceae (legume) family.[35] Whole grains are foods that contain all the elements of the original seed (bran, germ, and endosperm).[36] Nuts are dry fruits distinguishable by their woody shell.[33]

Fleshy fruits (distinguishable from dry fruits like grain, seeds and nuts) can be further classified as stone fruits (cherries and peaches), pome fruits (apples, pears), berries (blackberry, strawberry), citrus (oranges, lemon), melons (watermelon, cantaloupe), Mediterranean fruits (grapes, fig), tropical fruits (banana, pineapple).[33] Vegetables refer to any other part of the plant that can be eaten, including roots, stems, leaves, flowers, bark or the entire plant itself.[37] These include root vegetables (potatoes and carrots), bulbs (onion family), flowers (cauliflower and broccoli), leaf vegetables (spinach and lettuce) and stem vegetables (celery and asparagus).[38][37]

Plants have high carbohydrate, protein and lipid content, with carbohydrates mainly in the form of starch, fructose, glucose and other sugars.[29] Most vitamins are found from plant sources, with the notable exceptions of vitamin D and vitamin B12. Minerals are also plentiful, although the presence of phytates can prevent their release.[29] Fruit can consist of up to 90% water, contain high levels of simple sugars that contribute to their sweet taste and have a high vitamin C content.[29][33] Compared to fleshy fruit (excepting Bananas) vegetables are high in starch,[39] potassium, dietary fiber, folate and vitamins and low in fat and calories.[40] Grains are more starch based[29] and nuts have a high protein, fibre, vitamin E and B content.[33] Seeds are a good source of food for animals because they are abundant and contain fibre and healthful fats, such as omega-3 fats.[41][42]

Animals that only eat plants are called herbivores, with those that mostly just eat fruits known as frugivores,[43] leaves, while shoot eaters are folivores (pandas) and wood eaters termed xylophages (termites).[44] Frugivores include a diverse range of species from annelids to elephants, chimpanzees and many birds.[45][46][47] About 182 fish consume seeds or fruit.[48] There are many types of grasses, adapted to different locations, that animals (domesticated and wild) use as their main source of nutrients.[49]

Humans only eat about 200 out of the worlds 400 000 plant species, despite at least half of them being edible.[50] Most human plant-based food comes from maize, rice, and wheat.[50] Plants can be processed into breads, pasta, cereals, juices and jams or raw ingredients such as sugar, herbs, spices and oils can be extracted.[29] Oilseeds are often pressed to produce rich oils - sunflower, flaxseed, rapeseed (including canola oil) and sesame.[51]

Many plants and animals have coevolved in such a way that the fruit is good source of nutrition to the animal who then excretes the seeds some distance away allowing greater dispersal.[52] Even seed predation can be mutually beneficial as some seeds can survive the digestion process.[53][54] Insects are major eaters of seeds,[41] with ants being the only real seed dispersers.[55] Birds, although being major dispersers,[56] only rarely eat seeds as a source of food and can be identified by their thick beak that is used to crack open the seed coat.[57] Mammals eat a more diverse range of seeds as they are able to crush harder and larger seeds with their teeth.[58]

Animals

Animals are used as food either directly or indirectly. This includes meat, eggs, shellfish and dairy products like milk and cheese.[59] They are an important source or protein and are considered complete proteins for human consumption as they contain all the essential amino acids that the human body needs.[60] One 4-ounce (110 g) steak, chicken breast or pork chop contains about 30 grams of protein. One large egg has 7 grams of protein, a 4-ounce (110 g) serving of cheese about 15 grams and 1 cup of milk about 8.[60] Other nutrients found in animal products include calories, fat, essential vitamins (including B12) and minerals (including zinc, iron, calcium, magnesium).[60]

Food products produced by animals include milk produced by mammary glands, which in many cultures is drunk or processed into dairy products (cheese, butter, etc.). In addition, birds and other animals lay eggs, which are often eaten, and bees produce honey, a reduced nectar from flowers, which is a popular sweetener in many cultures. Some cultures consume blood, sometimes in the form of blood sausage, as a thickener for sauces, or in a cured, salted form for times of food scarcity, and others use blood in stews such as jugged hare.[61]

Some cultures and people do not consume meat or animal food products for cultural, dietary, health, ethical, or ideological reasons. Vegetarians choose to forgo food from animal sources to varying degrees. Vegans do not consume any foods that are or contain ingredients from an animal source.

Taste perception

Animals, specifically humans, have five different types of tastes: sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami. As animals have evolved, the tastes that provide the most energy (sugar and fats) are the most pleasant to eat while others, such as bitter, are not enjoyable.[62] Water, while important for survival, has no taste.[63] Fats, on the other hand, especially saturated fats, are thicker and rich and are thus considered more enjoyable to eat.

Sweet

Generally regarded as the most pleasant taste, sweetness is almost always caused by a type of simple sugar such as glucose or fructose, or disaccharides such as sucrose, a molecule combining glucose and fructose.[64] Complex carbohydrates are long chains and thus do not have the sweet taste. Artificial sweeteners such as sucralose are used to mimic the sugar molecule, creating the sensation of sweet, without the calories. Other types of sugar include raw sugar, which is known for its amber color, as it is unprocessed. As sugar is vital for energy and survival, the taste of sugar is pleasant.

The stevia plant contains a compound known as steviol which, when extracted, has 300 times the sweetness of sugar while having minimal impact on blood sugar.[65]

Sour

Sourness is caused by the taste of acids, such as vinegar in alcoholic beverages. Sour foods include citrus, specifically lemons, limes, and to a lesser degree oranges. Sour is evolutionarily significant as it is a sign for a food that may have gone rancid due to bacteria.[66] Many foods, however, are slightly acidic, and help stimulate the taste buds and enhance flavor.

Salty

Saltiness is the taste of alkali metal ions such as sodium and potassium. It is found in almost every food in low to moderate proportions to enhance flavor, although to eat pure salt is regarded as highly unpleasant. There are many different types of salt, with each having a different degree of saltiness, including sea salt, fleur de sel, kosher salt, mined salt, and grey salt. Other than enhancing flavor, its significance is that the body needs and maintains a delicate electrolyte balance, which is the kidney's function. Salt may be iodized, meaning iodine has been added to it, a necessary nutrient that promotes thyroid function. Some canned foods, notably soups or packaged broths, tend to be high in salt as a means of preserving the food longer. Historically salt has long been used as a meat preservative as salt promotes water excretion. Similarly, dried foods also promote food safety.

Bitter

Bitterness is a sensation often considered unpleasant characterized by having a sharp, pungent taste. Unsweetened dark chocolate, caffeine, lemon rind, and some types of fruit are known to be bitter.

Umami

Umami (/uːˈmɑːmi/ from Japanese: 旨味 Japanese pronunciation: [ɯmami]), or savoriness, is one of the five basic tastes.[67] It has been described as savory and is characteristic of broths and cooked meats.[68][69][70][71]: 35–36

People taste umami through taste receptors that typically respond to glutamates and nucleotides, which are widely present in meat broths and fermented products. Glutamates are commonly added to some foods in the form of monosodium glutamate (MSG), and nucleotides are commonly added in the form of inosine monophosphate (IMP) or guanosine monophosphate (GMP).[72][73][74] Since umami has its own receptors rather than arising out of a combination of the traditionally recognized taste receptors, scientists now consider umami to be a distinct taste.[67][75]

Foods that have a strong umami flavor include meats, shellfish, fish (including fish sauce and preserved fish such as maldive fish, sardines, and anchovies), tomatoes, mushrooms, hydrolyzed vegetable protein, meat extract, yeast extract, cheeses, and soy sauce.Cuisine

Many scholars claim that the rhetorical function of food is to represent the culture of a country, and that it can be used as a form of communication. According to Goode, Curtis and Theophano, food "is the last aspect of an ethnic culture to be lost".[76]

Many cultures have a recognizable cuisine, a specific set of cooking traditions using various spices or a combination of flavors unique to that culture, which evolves over time. Other differences include preferences (hot or cold, spicy, etc.) and practices, the study of which is known as gastronomy. Many cultures have diversified their foods by means of preparation, cooking methods, and manufacturing. This also includes a complex food trade which helps the cultures to economically survive by way of food, not just by consumption.

Some popular types of ethnic foods include Italian, French, Japanese, Chinese, American, Cajun, Thai, African, Indian and Nepalese. Various cultures throughout the world study the dietary analysis of food habits. While evolutionarily speaking, as opposed to culturally, humans are omnivores, religion and social constructs such as morality, activism, or environmentalism will often affect which foods they will consume. Food is eaten and typically enjoyed through the sense of taste, the perception of flavor from eating and drinking. Certain tastes are more enjoyable than others, for evolutionary purposes.

Presentation

Aesthetically pleasing and eye-appealing food presentations can encourage people to consume foods. A common saying is that people "eat with their eyes". Food presented in a clean and appetizing way will encourage a good flavor, even if unsatisfactory.[77][78]

Texture plays a crucial role in the enjoyment of eating foods. Contrasts in textures, such as something crunchy in an otherwise smooth dish, may increase the appeal of eating it. Common examples include adding granola to yogurt, adding croutons to a salad or soup, and toasting bread to enhance its crunchiness for a smooth topping, such as jam or butter.[79]

Another universal phenomenon regarding food is the appeal of contrast in taste and presentation. For example, such opposite flavors as sweetness and saltiness tend to go well together, as in kettle corn and nuts.

Food preparation

While many foods can be eaten raw, many also undergo some form of preparation for reasons of safety, palatability, texture, or flavor. At the simplest level this may involve washing, cutting, trimming, or adding other foods or ingredients, such as spices. It may also involve mixing, heating or cooling, pressure cooking, fermentation, or combination with other food. In a home, most food preparation takes place in a kitchen. Some preparation is done to enhance the taste or aesthetic appeal; other preparation may help to preserve the food; others may be involved in cultural identity. A meal is made up of food which is prepared to be eaten at a specific time and place.[80]

Animal preparation

The preparation of animal-based food usually involves slaughter, evisceration, hanging, portioning, and rendering. In developed countries, this is usually done outside the home in slaughterhouses, which are used to process animals en masse for meat production. Many countries regulate their slaughterhouses by law. For example, the United States has established the Humane Slaughter Act of 1958, which requires that an animal be stunned before killing. This act, like those in many countries, exempts slaughter in accordance with religious law, such as kosher, shechita, and dhabīḥah halal. Strict interpretations of kashrut require the animal to be fully aware when its carotid artery is cut.[81]

On the local level, a butcher may commonly break down larger animal meat into smaller manageable cuts, and pre-wrap them for commercial sale or wrap them to order in butcher paper. In addition, fish and seafood may be fabricated into smaller cuts by a fishmonger. However, fish butchery may be done on board a fishing vessel and quick-frozen for the preservation of quality.[82]

Raw food preparation

Certain cultures highlight animal and vegetable foods in a raw state. Salads consisting of raw vegetables or fruits are common in many cuisines. Sashimi in Japanese cuisine consists of raw sliced fish or other meat, and sushi often incorporates raw fish or seafood. Steak tartare and salmon tartare are dishes made from diced or ground raw beef or salmon, mixed with various ingredients and served with baguettes, brioche, or frites.[83] In Italy, carpaccio is a dish of very thinly sliced raw beef, drizzled with a vinaigrette made with olive oil.[84] The health food movement known as raw foodism promotes a mostly vegan diet of raw fruits, vegetables, and grains prepared in various ways, including juicing, food dehydration, sprouting, and other methods of preparation that do not heat the food above 118 °F (47.8 °C).[85] An example of a raw meat dish is ceviche, a Latin American dish made with raw meat that is "cooked" from the highly acidic citric juice from lemons and limes along with other aromatics such as garlic.

Cooking

The term "cooking" encompasses a vast range of methods, tools, and combinations of ingredients to improve the flavor or digestibility of food. Cooking technique, known as culinary art, generally requires the selection, measurement, and combining of ingredients in an ordered procedure in an effort to achieve the desired result. Constraints on success include the variability of ingredients, ambient conditions, tools, and the skill of the individual cook.[86] The diversity of cooking worldwide is a reflection of the myriad nutritional, aesthetic, agricultural, economic, cultural, and religious considerations that affect it.[87]

Cooking requires applying heat to a food which usually, though not always, chemically changes the molecules, thus changing its flavor, texture, appearance, and nutritional properties.[88] Cooking certain proteins, such as egg whites, meats, and fish, denatures the protein, causing it to firm. There is archaeological evidence of roasted foodstuffs at Homo erectus campsites dating from 420,000 years ago.[89] Boiling as a means of cooking requires a container, and has been practiced at least since the 10th millennium BC with the introduction of pottery.[90]

Cooking equipment

There are many different types of equipment used for cooking.

Ovens are mostly hollow devices that get very hot (up to 500 °F (260 °C)) and are used for baking or roasting and offer a dry-heat cooking method. Different cuisines will use different types of ovens. For example, Indian culture uses a tandoor oven, which is a cylindrical clay oven which operates at a single high temperature.[91] Western kitchens use variable temperature convection ovens, conventional ovens, toaster ovens, or non-radiant heat ovens like the microwave oven. Classic Italian cuisine includes the use of a brick oven containing burning wood. Ovens may be wood-fired, coal-fired, gas, electric, or oil-fired.[92]

Various types of cook-tops are used as well. They carry the same variations of fuel types as the ovens mentioned above. Cook-tops are used to heat vessels placed on top of the heat source, such as a sauté pan, sauce pot, frying pan, or pressure cooker. These pieces of equipment can use either a moist or dry cooking method and include methods such as steaming, simmering, boiling, and poaching for moist methods, while the dry methods include sautéing, pan frying, and deep-frying.[93]

In addition, many cultures use grills for cooking. A grill operates with a radiant heat source from below, usually covered with a metal grid and sometimes a cover. An open-pit barbecue in the American south is one example along with the American style outdoor grill fueled by wood, liquid propane, or charcoal along with soaked wood chips for smoking.[94] A Mexican style of barbecue is called barbacoa, which involves the cooking of meats such as whole sheep over an open fire. In Argentina, an asado (Spanish for "grilled") is prepared on a grill held over an open pit or fire made upon the ground, on which a whole animal or smaller cuts are grilled.[95]

Restaurants

.jpg.webp)

Restaurants employ chefs to prepare the food, and waiters to serve customers at the table.[96] The term restaurant comes from an old term for a restorative meat broth; this broth (or bouillon) was served in elegant outlets in Paris from the mid 18th century.[97][98] These refined "restaurants" were a marked change from the usual basic eateries such as inns and taverns,[98] and some had developed from early Parisian cafés, such as Café Procope, by first serving bouillon, then adding other cooked food to their menus.[99]

Commercial eateries existed during the Roman period, with evidence of 150 "thermopolia", a form of fast food restaurant, found in Pompeii,[100] and urban sales of prepared foods may have existed in China during the Song dynasty.[101]

In 2005, the population of the United States spent $496 billion on out-of-home dining. Expenditures by type of out-of-home dining were as follows: 40% in full-service restaurants, 37.2% in limited service restaurants (fast food), 6.6% in schools or colleges, 5.4% in bars and vending machines, 4.7% in hotels and motels, 4.0% in recreational places, and 2.2% in others, which includes military bases.[102]

Economy

Food systems have complex economic and social value chains that effect many parts of the global economy.

Production

.jpg.webp)

Most food has always been obtained through agriculture. With increasing concern over both the methods and products of modern industrial agriculture, there has been a growing trend toward sustainable agricultural practices. This approach, partly fueled by consumer demand, encourages biodiversity, local self-reliance and organic farming methods.[103] Major influences on food production include international organizations (e.g. the World Trade Organization and Common Agricultural Policy), national government policy (or law), and war.[104]

Several organisations have begun calling for a new kind of agriculture in which agroecosystems provide food but also support vital ecosystem services so that soil fertility and biodiversity are maintained rather than compromised. According to the International Water Management Institute and UNEP, well-managed agroecosystems not only provide food, fiber and animal products, they also provide services such as flood mitigation, groundwater recharge, erosion control and habitats for plants, birds, fish and other animals.[105]

Food manufacturing

.jpg.webp)

Packaged foods are manufactured outside the home for purchase. This can be as simple as a butcher preparing meat, or as complex as a modern international food industry. Early food processing techniques were limited by available food preservation, packaging, and transportation. This mainly involved salting, curing, curdling, drying, pickling, fermenting, and smoking.[106] Food manufacturing arose during the industrial revolution in the 19th century.[107] This development took advantage of new mass markets and emerging technology, such as milling, preservation, packaging and labeling, and transportation. It brought the advantages of pre-prepared time-saving food to the bulk of ordinary people who did not employ domestic servants.[108]

At the start of the 21st century, a two-tier structure has arisen, with a few international food processing giants controlling a wide range of well-known food brands. There also exists a wide array of small local or national food processing companies.[109] Advanced technologies have also come to change food manufacture. Computer-based control systems, sophisticated processing and packaging methods, and logistics and distribution advances can enhance product quality, improve food safety, and reduce costs.[108]

International food imports and exports

The World Bank reported that the European Union was the top food importer in 2005, followed at a distance by the US and Japan. Britain's need for food was especially well-illustrated in World War II. Despite the implementation of food rationing, Britain remained dependent on food imports and the result was a long-term engagement in the Battle of the Atlantic.

Food is traded and marketed on a global basis. The variety and availability of food is no longer restricted by the diversity of locally grown food or the limitations of the local growing season.[110] Between 1961 and 1999, there was a 400% increase in worldwide food exports.[111] Some countries are now economically dependent on food exports, which in some cases account for over 80% of all exports.[112]

In 1994, over 100 countries became signatories to the Uruguay Round of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade in a dramatic increase in trade liberalization. This included an agreement to reduce subsidies paid to farmers, underpinned by the WTO enforcement of agricultural subsidy, tariffs, import quotas, and settlement of trade disputes that cannot be bilaterally resolved.[113] Where trade barriers are raised on the disputed grounds of public health and safety, the WTO refer the dispute to the Codex Alimentarius Commission, which was founded in 1962 by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization and the World Health Organization. Trade liberalization has greatly affected world food trade.[114]

Marketing and retailing

Food marketing brings together the producer and the consumer. The marketing of even a single food product can be a complicated process involving many producers and companies. For example, 56 companies are involved in making one can of chicken noodle soup. These businesses include not only chicken and vegetable processors but also the companies that transport the ingredients and those who print labels and manufacture cans.[115] The food marketing system is the largest direct and indirect non-government employer in the United States.

In the pre-modern era, the sale of surplus food took place once a week when farmers took their wares on market day into the local village marketplace. Here food was sold to grocers for sale in their local shops for purchase by local consumers.[87][108] With the onset of industrialization and the development of the food processing industry, a wider range of food could be sold and distributed in distant locations. Typically early grocery shops would be counter-based shops, in which purchasers told the shop-keeper what they wanted, so that the shop-keeper could get it for them.[87][116]

In the 20th century, supermarkets were born. Supermarkets brought with them a self service approach to shopping using shopping carts, and were able to offer quality food at lower cost through economies of scale and reduced staffing costs. In the latter part of the 20th century, this has been further revolutionized by the development of vast warehouse-sized, out-of-town supermarkets, selling a wide range of food from around the world.[117]

Unlike food processors, food retailing is a two-tier market in which a small number of very large companies control a large proportion of supermarkets. The supermarket giants wield great purchasing power over farmers and processors, and strong influence over consumers. Nevertheless, less than 10% of consumer spending on food goes to farmers, with larger percentages going to advertising, transportation, and intermediate corporations.[118]

Prices

Food prices refer to the average price level for food across countries, regions and on a global scale.[119] Food prices have an impact on producers and consumers of food.

Price levels depend on the food production process, including food marketing and food distribution. Fluctuation in food prices is determined by a number of compounding factors.[120] Geopolitical events, global demand, exchange rates,[121] government policy, diseases and crop yield, energy costs, availability of natural resources for agriculture,[122] food speculation,[123][124][125] changes in the use of soil and weather events have a direct impact on the increase or decrease of food prices.[126]

The consequences of food price fluctuation are multiple. Increases in food prices, or agflation, endangers food security, particularly for developing countries, and can cause social unrest.[127][128][129] Increases in food prices is related to disparities in diet quality and health,[130] particularly among vulnerable populations, such as women and children.[131]

Food prices will on average continue to rise due to a variety of reasons. Growing world population will put more pressure on the supply and demand. Climate change will increase extreme weather events, including droughts, storms and heavy rain, and overall increases in temperature will have an impact on food production.[132]

To a certain extent, adverse price trends can be counteracted by food politics.

An intervention to reduce food loss or waste, if sufficiently large, will affect prices upstream and downstream in the supply chain relative to where the intervention occurred.[133] "The CPI (Consumer Price Index) for all food increased 0.8% from July 2022 to August 2022, and food prices were 11.4% higher than in August 2021."[134]As investment

Food speculation is betting on food prices (unregulated) financial markets. Food speculation by global players like banks, hedge funds or pension funds is alleged to cause price swings in staple foods such as wheat, maize and soy – even though too large price swings in an idealized economy are theoretically ruled out: Adam Smith in 1776 reasoned that the only way to make money from commodities trading is by buying low and selling high, which has the effect of smoothing out price swings and mitigating shortages.[135][136] For the actors, the apparently random swings are predictable, which means potential huge profits. For the global poor, food speculation and resulting price peaks may result in increased poverty or even famine.[137]

In contrast to food hoarding, speculation does not mean that real food shortages or scarcity need to be evoked, the price changes are only due to trading activity.[138]

Food speculation may be a reason for agflation.[139] The 2007–08 world food price crisis is thought to have been be partially caused by speculation.[138][140][141]Problems

Because of its centrality to human life, problems related to access, quality and production of food effect every aspect of human life.

Nutrition and dietary problems

Between the extremes of optimal health and death from starvation or malnutrition, there is an array of disease states that can be caused or alleviated by changes in diet. Deficiencies, excesses, and imbalances in diet can produce negative impacts on health, which may lead to various health problems such as scurvy, obesity, or osteoporosis, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases as well as psychological and behavioral problems. The science of nutrition attempts to understand how and why specific dietary aspects influence health.

Nutrients in food are grouped into several categories. Macronutrients are fat, protein, and carbohydrates. Micronutrients are the minerals and vitamins. Additionally, food contains water and dietary fiber.

As previously discussed, the body is designed by natural selection to enjoy sweet and fattening foods for evolutionary diets, ideal for hunters and gatherers. Thus, sweet and fattening foods in nature are typically rare and are very pleasurable to eat. In modern times, with advanced technology, enjoyable foods are easily available to consumers. Unfortunately, this promotes obesity in adults and children alike.

Hunger and starvation

Food deprivation leads to malnutrition and ultimately starvation. This is often connected with famine, which involves the absence of food in entire communities. This can have a devastating and widespread effect on human health and mortality. Rationing is sometimes used to distribute food in times of shortage, most notably during times of war.[104]

Starvation is a significant international problem. Approximately 815 million people are undernourished, and over 16,000 children die per day from hunger-related causes.[142] Food deprivation is regarded as a deficit need in Maslow's hierarchy of needs and is measured using famine scales.[143]

Food waste

.jpg.webp)

Food loss and waste is food that is not eaten. The causes of food waste or loss are numerous and occur throughout the food system, during production, processing, distribution, retail and food service sales, and consumption. Overall, about one-third of the world's food is thrown away.[145][146] A 2021 metaanalysis that did not include food lost during production, by the United Nations Environment Programme found that food waste was a challenge in all countries at all levels of economic development.[147] The analysis estimated that global food waste was 931 million tonnes of food waste (about 121 kg per capita) across three sectors: 61 per cent from households, 26 per cent from food service and 13 per cent from retail.[147]

Food loss and waste is a major part of the impact of agriculture on climate change (it amounts to 3.3 billion tons of CO2e emissions annually[148][149]) and other environmental issues, such as land use, water use and loss of biodiversity. Prevention of food waste is the highest priority, and when prevention is not possible, the food waste hierarchy ranks the food waste treatment options from preferred to least preferred based on their negative environmental impacts.[150] Reuse pathways of surplus food intended for human consumption, such as food donation, is the next best strategy after prevention, followed by animal feed, recycling of nutrients and energy followed by the least preferred option, landfill, which is a major source of the greenhouse gas methane.[151] Other considerations include unreclaimed phosphorus in food waste leading to further phosphate mining. Moreover, reducing food waste in all parts of the food system is an important part of reducing the environmental impact of agriculture, by reducing the total amount of water, land, and other resources used.

The UN's Sustainable Development Goal Target 12.3 seeks to "halve global per capita food waste at the retail and consumer levels and reduce food losses along production and supply chains, including post-harvest losses" by 2030.[152] Climate change mitigation strategies prominently feature reducing food waste.[153]Policy

Food policy is the area of public policy concerning how food is produced, processed, distributed, purchased, or provided. Food policies are designed to influence the operation of the food and agriculture system balanced with ensuring human health needs. This often includes decision-making around production and processing techniques, marketing, availability, utilization, and consumption of food, in the interest of meeting or furthering social objectives. Food policy can be promulgated on any level, from local to global, and by a government agency, business, or organization. Food policymakers engage in activities such as regulation of food-related industries, establishing eligibility standards for food assistance programs for the poor, ensuring safety of the food supply, food labeling, and even the qualifications of a product to be considered organic.[154]

Most food policy is initiated at the domestic level for purposes of ensuring a safe and adequate food supply for the citizenry.[155] In a developing nation, there are three main objectives for food policy: to protect the poor from crises, to develop long-run markets that enhance efficient resource use, and to increase food production that will in turn promote an increase in income.[156]

Food policy comprises the mechanisms by which food-related matters are addressed or administered by governments, including international bodies or networks, and by public institutions or private organizations. Agricultural producers often bear the burden of governments' desire to keep food prices sufficiently low for growing urban populations. Low prices for consumers can be a disincentive for farmers to produce more food, often resulting in hunger, poor trade prospects, and an increased need for food imports.[155]

In a more developed country such as the United States, food and nutrition policy must be viewed in context with regional and national economic concerns, environmental pressures, maintenance of a social safety net, health, encouragement of private enterprise and innovation, and an agrarian landscape dominated by fewer, larger mechanized farms.[157] Industrialized countries strive to ensure that farmers earn relatively stable incomes despite price and supply fluctuations and adverse weather events. The cost of subsidizing farm incomes is passed along to consumers in the form of higher food prices.[155]Legal definition

Some countries list a legal definition of food, often referring them with the word foodstuff. These countries list food as any item that is to be processed, partially processed, or unprocessed for consumption. The listing of items included as food includes any substance intended to be, or reasonably expected to be, ingested by humans. In addition to these foodstuffs, drink, chewing gum, water, or other items processed into said food items are part of the legal definition of food. Items not included in the legal definition of food include animal feed, live animals (unless being prepared for sale in a market), plants prior to harvesting, medicinal products, cosmetics, tobacco and tobacco products, narcotic or psychotropic substances, and residues and contaminants.[158]

Right to food

The right to food, and its variations, is a human right protecting the right of people to feed themselves in dignity, implying that sufficient food is available, that people have the means to access it, and that it adequately meets the individual's dietary needs. The right to food protects the right of all human beings to be free from hunger, food insecurity and malnutrition.[162] The right to food does not imply that governments have an obligation to hand out free food to everyone who wants it, or a right to be fed. However, if people are deprived of access to food for reasons beyond their control, for example, because they are in detention, in times of war or after natural disasters, the right requires the government to provide food directly.[163]

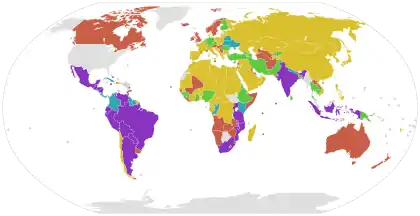

The right is derived from the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights[163] which has 170 state parties as of April 2020.[160] States that sign the covenant agree to take steps to the maximum of their available resources to achieve progressively the full realization of the right to adequate food, both nationally and internationally.[164][162] In a total of 106 countries the right to food is applicable either via constitutional arrangements of various forms or via direct applicability in law of various international treaties in which the right to food is protected.[165]

At the 1996 World Food Summit, governments reaffirmed the right to food and committed themselves to halve the number of hungry and malnourished from 840 to 420 million by 2015. However, the number has increased over the past years, reaching an infamous record in 2009 of more than 1 billion undernourished people worldwide.[162] Furthermore, the number who suffer from hidden hunger – micronutrient deficiences that may cause stunted bodily and intellectual growth in children – amounts to over 2 billion people worldwide.[166]

Whilst under international law states are obliged to respect, protect and fulfill the right to food, the practical difficulties in achieving this human right are demonstrated by prevalent food insecurity across the world, and ongoing litigation in countries such as India.[167][168] In the continents with the biggest food-related problems – Africa, Asia and South America – not only is there shortage of food and lack of infrastructure but also maldistribution and inadequate access to food.[169]

The Human Rights Measurement Initiative[170] measures the right to food for countries around the world, based on their level of income.[171]Food security

Food security is the measure of the availability of food and individuals' ability to access it. According to the United Nations' Committee on World Food Security, food security is defined as meaning that all people, at all times, have physical, social, and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meets their food preferences and dietary needs for an active and healthy life.[172] The availability of food irrespective of class, gender or region is another one. There is evidence of food security being a concern many thousands of years ago, with central authorities in ancient China and ancient Egypt being known to release food from storage in times of famine. At the 1974 World Food Conference, the term "food security" was defined with an emphasis on supply; food security is defined as the "availability at all times of adequate, nourishing, diverse, balanced and moderate world food supplies of basic foodstuffs to sustain a steady expansion of food consumption and to offset fluctuations in production and prices".[173] Later definitions added demand and access issues to the definition. The first World Food Summit, held in 1996, stated that food security "exists when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life."[174][175]

Similarly, household food security is considered to exist when all members, at all times, have access to enough food for an active, healthy life.[176] Individuals who are food secure do not live in hunger or fear of starvation.[177] Food insecurity, on the other hand, is defined by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) as a situation of "limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods or limited or uncertain ability to acquire acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways".[178] Food security incorporates a measure of resilience to future disruption or unavailability of critical food supply due to various risk factors including droughts, shipping disruptions, fuel shortages, economic instability, and wars.[179]

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, or FAO, identified the four pillars of food security as availability, access, utilization, and stability.[180] The United Nations (UN) recognized the Right to Food in the Declaration of Human Rights in 1948,[177] and has since said that it is vital for the enjoyment of all other rights.[181]

The 1996 World Summit on Food Security declared that "food should not be used as an instrument for political and economic pressure".[175] Multiple different international agreements and mechanisms have been developed to address food security. The main global policy to reduce hunger and poverty is in the Sustainable Development Goals. In particular Goal 2: Zero Hunger sets globally agreed on targets to end hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture by 2030.[182]International aid

Food aid can benefit people suffering from a shortage of food. It can be used to improve peoples' lives in the short term, so that a society can increase its standard of living to the point that food aid is no longer required.[183] Conversely, badly managed food aid can create problems by disrupting local markets, depressing crop prices, and discouraging food production. Sometimes a cycle of food aid dependence can develop.[184] Its provision, or threatened withdrawal, is sometimes used as a political tool to influence the policies of the destination country, a strategy known as food politics. Sometimes, food aid provisions will require certain types of food be purchased from certain sellers, and food aid can be misused to enhance the markets of donor countries.[185] International efforts to distribute food to the neediest countries are often coordinated by the World Food Programme.[186]

Safety

Foodborne illness, commonly called "food poisoning", is caused by bacteria, toxins, viruses, parasites, and prions. Roughly 7 million people die of food poisoning each year, with about 10 times as many suffering from a non-fatal version.[187] The two most common factors leading to cases of bacterial foodborne illness are cross-contamination of ready-to-eat food from other uncooked foods and improper temperature control. Less commonly, acute adverse reactions can also occur if chemical contamination of food occurs, for example from improper storage, or use of non-food grade soaps and disinfectants. Food can also be adulterated by a very wide range of articles (known as "foreign bodies") during farming, manufacture, cooking, packaging, distribution, or sale. These foreign bodies can include pests or their droppings, hairs, cigarette butts, wood chips, and all manner of other contaminants. It is possible for certain types of food to become contaminated if stored or presented in an unsafe container, such as a ceramic pot with lead-based glaze.[187]

Food poisoning has been recognized as a disease since as early as Hippocrates.[188] The sale of rancid, contaminated, or adulterated food was commonplace until the introduction of hygiene, refrigeration, and vermin controls in the 19th century. Discovery of techniques for killing bacteria using heat, and other microbiological studies by scientists such as Louis Pasteur, contributed to the modern sanitation standards that are ubiquitous in developed nations today. This was further underpinned by the work of Justus von Liebig, which led to the development of modern food storage and food preservation methods.[189] In more recent years, a greater understanding of the causes of food-borne illnesses has led to the development of more systematic approaches such as the Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP), which can identify and eliminate many risks.[190]

Recommended measures for ensuring food safety include maintaining a clean preparation area with foods of different types kept separate, ensuring an adequate cooking temperature, and refrigerating foods promptly after cooking.[191]

Foods that spoil easily, such as meats, dairy, and seafood, must be prepared a certain way to avoid contaminating the people for whom they are prepared. As such, the rule of thumb is that cold foods (such as dairy products) should be kept cold and hot foods (such as soup) should be kept hot until storage. Cold meats, such as chicken, that are to be cooked should not be placed at room temperature for thawing, at the risk of dangerous bacterial growth, such as Salmonella or E. coli.[192]

Allergies

Some people have allergies or sensitivities to foods that are not problematic to most people. This occurs when a person's immune system mistakes a certain food protein for a harmful foreign agent and attacks it. About 2% of adults and 8% of children have a food allergy.[193] The amount of the food substance required to provoke a reaction in a particularly susceptible individual can be quite small. In some instances, traces of food in the air, too minute to be perceived through smell, have been known to provoke lethal reactions in extremely sensitive individuals. Common food allergens are gluten, corn, shellfish (mollusks), peanuts, and soy.[193] Allergens frequently produce symptoms such as diarrhea, rashes, bloating, vomiting, and regurgitation. The digestive complaints usually develop within half an hour of ingesting the allergen.[193]

Rarely, food allergies can lead to a medical emergency, such as anaphylactic shock, hypotension (low blood pressure), and loss of consciousness. An allergen associated with this type of reaction is peanut, although latex products can induce similar reactions.[193] Initial treatment is with epinephrine (adrenaline), often carried by known patients in the form of an Epi-pen or Twinject.[194][195]

Other health issues

Human diet was estimated to cause perhaps around 35% of cancers in a human epidemiological analysis by Richard Doll and Richard Peto in 1981.[196] These cancer may be caused by carcinogens that are present in food naturally or as contaminants. Food contaminated with fungal growth may contain mycotoxins such as aflatoxins which may be found in contaminated corn and peanuts. Other carcinogens identified in food include heterocyclic amines generated in meat when cooked at high temperature, polyaromatic hydrocarbons in charred meat and smoked fish, and nitrosamines generated from nitrites used as food preservatives in cured meat such as bacon.[197]

Anticarcinogens that may help prevent cancer can also be found in many food especially fruit and vegetables. Antioxidants are important groups of compounds that may help remove potentially harmful chemicals. It is however often difficult to identify the specific components in diet that serve to increase or decrease cancer risk since many food, such as beef steak and broccoli, contain low concentrations of both carcinogens and anticarcinogens.[197] There are many international certifications in the cooking field, such as Monde Selection, A.A. Certification, iTQi. They use high-quality evaluation methods to make the food safer.

Diet

Other area (Yr 2010)[200] * Africa, sub-Sahara - 2170 kcal/capita/day * N.E. and N. Africa - 3120 kcal/capita/day * South Asia - 2450 kcal/capita/day * East Asia - 3040 kcal/capita/day * Latin America / Caribbean - 2950 kcal/capita/day * Developed countries - 3470 kcal/capita/day

Cultural and religious diets

Many cultures hold some food preferences and some food taboos. Dietary choices can also define cultures and play a role in religion. For example, only kosher foods are permitted by Judaism, halal foods by Islam, and in Hinduism beef is restricted.[201] In addition, the dietary choices of different countries or regions have different characteristics. This is highly related to a culture's cuisine.

Diet deficiencies

Dietary habits play a significant role in the health and mortality of all humans. Imbalances between the consumed fuels and expended energy results in either starvation or excessive reserves of adipose tissue, known as body fat.[202] Poor intake of various vitamins and minerals can lead to diseases that can have far-reaching effects on health. For instance, 30% of the world's population either has, or is at risk for developing, iodine deficiency.[203] It is estimated that at least 3 million children are blind due to vitamin A deficiency.[204] Vitamin C deficiency results in scurvy.[205] Calcium, vitamin D, and phosphorus are inter-related; the consumption of each may affect the absorption of the others. Kwashiorkor and marasmus are childhood disorders caused by lack of dietary protein.[206]

Moral, ethical, and health-conscious diets

Many individuals limit what foods they eat for reasons of morality or other habits. For instance, vegetarians choose to forgo food from animal sources to varying degrees. Others choose a healthier diet, avoiding sugars or animal fats and increasing consumption of dietary fiber and antioxidants.[207] Obesity, a serious problem in the western world, leads to higher chances of developing heart disease, diabetes, cancer and many other diseases.[208] More recently, dietary habits have been influenced by the concerns that some people have about possible impacts on health or the environment from genetically modified food.[209] Further concerns about the impact of industrial farming (grains) on animal welfare, human health, and the environment are also having an effect on contemporary human dietary habits. This has led to the emergence of a movement with a preference for organic and local food.[210]

See also

- Bulk foods

- Beverages

- Food and Bioprocess Technology

- Food engineering

- Food, Inc., a 2009 documentary

- Food science

- Future food technology

- Industrial crop

- List of foods

- Lists of prepared foods

- Optimal foraging theory

- Outline of cooking

- Outline of nutrition

- Right to food by country

References

- SAPEA (2020). A sustainable food system for the European Union (PDF). Berlin: Science Advice for Policy by European Academies. p. 39. doi:10.26356/sustainablefood. ISBN 978-3-9820301-7-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 April 2020. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- "Food definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary". www.collinsdictionary.com. Archived from the original on 2021-05-01. Retrieved 2021-08-21.

- "Low-Energy-Dense Foods and Weight Management: Cutting Calories While Controlling Hunger" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-11-18. Retrieved 2021-12-03.

- Rahman, M. Shafiur; McCarthy, Owen J. (July 1999). "A classification of food properties". International Journal of Food Properties. 2 (2): 93–99. doi:10.1080/10942919909524593. ISSN 1094-2912.

- "What is Photosynthesis". Smithsonian Science Education Center. 2017-04-12. Archived from the original on 2021-12-03. Retrieved 2021-12-03.

- Affairs, Office of Regulatory (2020-02-11). "CPG Sec 555.875 Water in Food Products (Ingredient or Adulterant)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 2021-12-03. Retrieved 2021-12-03.

- Zoroddu, Maria Antonietta; Aaseth, Jan; Crisponi, Guido; Medici, Serenella; Peana, Massimiliano; Nurchi, Valeria Marina (2019-06-01). "The essential metals for humans: a brief overview". Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry. 195: 120–129. doi:10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2019.03.013. ISSN 0162-0134. PMID 30939379. S2CID 92997696. Archived from the original on 2022-04-11. Retrieved 2022-04-11.

- Sadler, Christina R.; Grassby, Terri; Hart, Kathryn; Raats, Monique; Sokolović, Milka; Timotijevic, Lada (2021-06-01). "Processed food classification: Conceptualisation and challenges". Trends in Food Science & Technology. 112: 149–162. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2021.02.059. ISSN 0924-2244. S2CID 233647428. Archived from the original on 2021-12-03. Retrieved 2021-12-03.

- Nestle, Marion (2013) [2002]. Food Politics: How the Food Industry Influences Nutrition and Health. University of California Press. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-0-520-27596-6.

- Schwingshackl, Lukas; Schwedhelm, Carolina; Hoffmann, Georg; Lampousi, Anna-Maria; Knüppel, Sven; Iqbal, Khalid; Bechthold, Angela; Schlesinger, Sabrina; Boeing, Heiner (2017). "Food groups and risk of all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 105 (6): 1462–1473. doi:10.3945/ajcn.117.153148. ISSN 0002-9165. PMID 28446499. S2CID 22494319.

- Schwingshackl, Lukas; Schwedhelm, Carolina; Hoffmann, Georg; Knüppel, Sven; Preterre, Anne Laure; Iqbal, Khalid; Bechthold, Angela; Henauw, Stefaan De; Michels, Nathalie; Devleesschauwer, Brecht; Boeing, Heiner (2018). "Food groups and risk of colorectal cancer". International Journal of Cancer. 142 (9): 1748–1758. doi:10.1002/ijc.31198. ISSN 1097-0215. PMID 29210053.

- Schwingshackl, Lukas; Hoffmann, Georg; Lampousi, Anna-Maria; Knüppel, Sven; Iqbal, Khalid; Schwedhelm, Carolina; Bechthold, Angela; Schlesinger, Sabrina; Boeing, Heiner (May 2017). "Food groups and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies". European Journal of Epidemiology. 32 (5): 363–375. doi:10.1007/s10654-017-0246-y. ISSN 0393-2990. PMC 5506108. PMID 28397016.

- "Food groups and sub-groups". FAO. Archived from the original on 2021-08-29. Retrieved 2021-08-29.

- "Food Web: Concept and Applications | Learn Science at Scitable". www.nature.com. Archived from the original on 2022-02-09. Retrieved 2021-12-15.

- Allan, J. David; Castillo, Marí M. (2007). "Primary producers". Stream Ecology: Structure and function of running waters. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. pp. 105–134. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-5583-6_6. ISBN 978-1-4020-5583-6.

- Society, National Geographic (2011-01-21). "omnivore". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 2021-12-15. Retrieved 2021-12-15.

- Wallach, Arian D.; Izhaki, Ido; Toms, Judith D.; Ripple, William J.; Shanas, Uri (2015). "What is an apex predator?". Oikos. 124 (11): 1453–1461. doi:10.1111/oik.01977. Archived from the original on 2021-12-15. Retrieved 2021-12-15.

- Roopnarine, Peter D. (2014-03-04). "Humans are apex predators". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (9): E796. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111E.796R. doi:10.1073/pnas.1323645111. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3948303. PMID 24497513.

- Society, National Geographic (1 March 2011). "food". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 22 March 2017. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- "ProdSTAT". FAOSTAT. Archived from the original on 10 February 2012.

- Favour, Eboh. "Design and Fabrication of a Mill Pulverizer". Academia. Archived from the original on 26 December 2017.

- Engineers, NIIR Board of Consultants & (2006). The Complete Book on Spices & Condiments (with Cultivation, Processing & Uses) 2nd Revised Edition: With Cultivation, Processing & Uses. Asia Pacific Business Press Inc. ISBN 978-81-7833-038-9. Archived from the original on 26 December 2017.

- Plumer, Brad (2014-08-21). "How much of the world's cropland is actually used to grow food?". Vox. Archived from the original on 2022-04-12. Retrieved 2022-04-11.

- Palombo, Enzo. "Kitchen Science: bacteria and fungi are your foody friends". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 2022-04-11. Retrieved 2022-04-11.

- Messinger, Johannes; Ishitani, Osamu; Wang, Dunwei (2018). "Artificial photosynthesis – from sunlight to fuels and valuable products for a sustainable future". Sustainable Energy & Fuels. 2 (9): 1891–1892. doi:10.1039/C8SE90049C. ISSN 2398-4902. Archived from the original on 2022-07-30. Retrieved 2022-04-11.

- "Oceanic Bacteria Trap Vast Amounts of Light Without Chlorophyll". The Scientist Magazine®. Archived from the original on 2022-04-06. Retrieved 2022-04-11.

- Leslie, Mitch (2009-03-06). "On the Origin of Photosynthesis". Science. 323 (5919): 1286–1287. doi:10.1126/science.323.5919.1286. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 19264999. S2CID 206584539. Archived from the original on 2022-04-11. Retrieved 2022-04-11.

- Society, National Geographic (2019-10-24). "Photosynthesis". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 2022-04-12. Retrieved 2022-04-11.

- Fardet, Anthony (2017), "New Concepts and Paradigms for the Protective Effects of Plant-Based Food Components in Relation to Food Complexity", Vegetarian and Plant-Based Diets in Health and Disease Prevention, Elsevier, pp. 293–312, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-803968-7.00016-2, ISBN 978-0-12-803968-7, archived from the original on 2022-06-15, retrieved 2022-04-12

- "FAQs". vric.ucdavis.edu. Archived from the original on 2021-03-21. Retrieved 2022-04-12.

- "Nuts". www.fs.fed.us. Archived from the original on 2022-02-27. Retrieved 2022-04-17.

- Chodosh, Sara (2021-07-08). "The bizarre botany that makes corn a fruit, a grain, and also (kind of) a vegetable". Popular Science. Archived from the original on 2022-04-09. Retrieved 2022-04-17.

- Rejman, Krystyna; Górska-Warsewicz, Hanna; Kaczorowska, Joanna; Laskowski, Wacław (2021-06-17). "Nutritional Significance of Fruit and Fruit Products in the Average Polish Diet". Nutrients. 13 (6): 2079. doi:10.3390/nu13062079. ISSN 2072-6643. PMC 8235518. PMID 34204541.

- Thomson, Julie (2017-06-13). "Quinoa's 'Seed Or Grain' Debate Ends Right Here". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 2022-04-15. Retrieved 2022-04-15.

- "Legumes and Pulses". The Nutrition Source. 2019-10-28. Archived from the original on 2022-04-21. Retrieved 2022-04-15.

- "Definition of a Whole Grain | The Whole Grains Council". wholegrainscouncil.org. Archived from the original on 2022-01-31. Retrieved 2022-04-15.

- "Vegetables: Foods from Roots, Stems, Bark, and Leaves". U.S. Forest Service. Archived from the original on 2022-04-17. Retrieved 2022-04-12.

- "Vegetable Classifications". Vegetables. Archived from the original on 2022-02-04. Retrieved 2022-04-12.

- Slavin, Joanne L.; Lloyd, Beate (2012-07-01). "Health Benefits of Fruits and Vegetables". Advances in Nutrition. 3 (4): 506–516. doi:10.3945/an.112.002154. ISSN 2156-5376. PMC 3649719. PMID 22797986.

- "Vegetables". www.myplate.gov. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original on 2022-04-17. Retrieved 2022-04-17.

- Lundgren, Jonathan G.; Rosentrater, Kurt A. (2007-09-13). "The strength of seeds and their destruction by granivorous insects". Arthropod-Plant Interactions. 1 (2): 93–99. doi:10.1007/s11829-007-9008-1. ISSN 1872-8855. S2CID 6410974. Archived from the original on 2022-07-30. Retrieved 2022-04-15.

- "The nutrition powerhouse we should eat more of". BBC Food. Archived from the original on 2022-04-12. Retrieved 2022-04-12.

- Kanchwala, Hussain (2019-03-21). "What Are Frugivores?". Science ABC. Archived from the original on 2022-05-16. Retrieved 2022-04-17.

- Society, National Geographic (2011-01-21). "Herbivore". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 2022-04-08. Retrieved 2022-04-17.

- Hagen, Melanie; Kissling, W. Daniel; Rasmussen, Claus; De Aguiar, Marcus A.M.; Brown, Lee E.; Carstensen, Daniel W.; Alves-Dos-Santos, Isabel; Dupont, Yoko L.; Edwards, Francois K. (2012), "Biodiversity, Species Interactions and Ecological Networks in a Fragmented World", Advances in Ecological Research, Elsevier, vol. 46, pp. 89–210, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-396992-7.00002-2, ISBN 978-0-12-396992-7, archived from the original on 2022-05-04, retrieved 2022-04-17

- Scanes, Colin G. (2018), "Animals and Hominid Development", Animals and Human Society, Elsevier, pp. 83–102, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-805247-1.00005-8, ISBN 978-0-12-805247-1, archived from the original on 2018-06-09, retrieved 2022-04-17

- Fleming, Theodore H. (1992), "How Do Fruit- and Nectar-Feeding Birds and Mammals Track Their Food Resources?", Effects of Resource Distribution on Animal–Plant Interactions, Elsevier, pp. 355–391, doi:10.1016/b978-0-08-091881-5.50015-3, ISBN 978-0-12-361955-6, archived from the original on 2021-05-25, retrieved 2022-04-17

- Correa, Sandra Bibiana; Winemiller, Kirk O.; LóPez-Fernández, Hernán; Galetti, Mauro (2007-10-01). "Evolutionary Perspectives on Seed Consumption and Dispersal by Fishes". BioScience. 57 (9): 748–756. doi:10.1641/B570907. ISSN 0006-3568. S2CID 13869429.

- "Describe the utilization of grass in forage-livestock systems". Forage Information System. 2009-05-28. Archived from the original on 2022-01-23. Retrieved 2022-04-12.

- Warren, John. "Why do we consume only a tiny fraction of the world's edible plants?". World Economic Forum. Archived from the original on 2022-04-12. Retrieved 2022-04-12.

- McGee, Chapter 9.

- Eriksson, Ove (December 20, 2014). "Evolution of angiosperm seed disperser mutualisms: the timing of origins and their consequences for coevolutionary interactions between angiosperms and frugivores". Biological Reviews. 91 (1): 168–186. doi:10.1111/brv.12164. PMID 25530412.

- Heleno, Ruben H.; Ross, Georgina; Everard, Amy; Memmott, Jane; Ramos, Jaime A. (2011). "The role of avian 'seed predators' as seed dispersers: Seed predators as seed dispersers". Ibis. 153 (1): 199–203. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.2010.01088.x. hdl:10316/41308. Archived from the original on 2022-04-15. Retrieved 2022-04-15.

- Spengler, Robert N. (2020-04-01). "Anthropogenic Seed Dispersal: Rethinking the Origins of Plant Domestication". Trends in Plant Science. 25 (4): 340–348. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2020.01.005. ISSN 1360-1385. PMID 32191870. S2CID 213192873. Archived from the original on 2022-07-30. Retrieved 2022-04-15.

- Simms, Ellen L. (2001-01-01), "Plant-Animal Interactions", in Levin, Simon Asher (ed.), Encyclopedia of Biodiversity, New York: Elsevier, pp. 601–619, doi:10.1016/b0-12-226865-2/00340-0, ISBN 978-0-12-226865-6, archived from the original on 2022-04-15, retrieved 2022-04-15

- Godínez‐Alvarez, Héctor; Ríos‐Casanova, Leticia; Peco, Begoña (2020). "Are large frugivorous birds better seed dispersers than medium‐ and small‐sized ones? Effect of body mass on seed dispersal effectiveness". Ecology and Evolution. 10 (12): 6136–6143. doi:10.1002/ece3.6285. ISSN 2045-7758. PMC 7319144. PMID 32607219.

- Jennings, Elizabeth (November 15, 2019). "How Much Seed Do Birds Eat In a Day?". Sciencing. Archived from the original on 2022-01-12. Retrieved 2022-04-14.

- Carpenter, Joanna K.; Wilmshurst, Janet M.; McConkey, Kim R.; Hume, Julian P.; Wotton, Debra M.; Shiels, Aaron B.; Burge, Olivia R.; Drake, Donald R. (2020). Barton, Kasey (ed.). "The forgotten fauna: Native vertebrate seed predators on islands". Functional Ecology. 34 (9): 1802–1813. doi:10.1111/1365-2435.13629. ISSN 0269-8463. S2CID 225292938.

- "Animal Products". www.ksre.k-state.edu. Archived from the original on 2022-03-20. Retrieved 2022-05-12.

- Marcus, Jacqueline B. (2013), "Protein Basics: Animal and Vegetable Proteins in Food and Health", Culinary Nutrition, Elsevier, pp. 189–230, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-391882-6.00005-4, ISBN 978-0-12-391882-6, archived from the original on 2018-06-26, retrieved 2022-05-13

- Davidson, 81–82.

- "Evolution of taste receptor may have shaped human sensitivity to toxic compounds". Medical News Today. Archived from the original on 27 September 2010. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- "Why does pure water have no taste or colour?". The Times Of India. 3 April 2004. Archived from the original on 30 December 2015.

- New Oxford American Dictionary

- The sweetness multiplier "300 times" comes from subjective evaluations by a panel of test subjects Archived 23 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine tasting various dilutions compared to a standard dilution of sucrose. Sources referenced in this article say steviosides have up to 250 times the sweetness of sucrose, but others, including stevioside brands such as SweetLeaf, claim 300 times. 1/3 to 1/2 teaspoon (1.6–2.5 ml) of stevioside powder is claimed to have equivalent sweetening power to 1 cup (237 ml) of sugar.

- States "having an acid taste like lemon or vinegar: she sampled the wine and found it was sour. (of food, esp. milk) spoiled because of fermentation." New Oxford American Dictionary

- Torii K, Uneyama H, Nakamura E (April 2013). "Physiological roles of dietary glutamate signaling via gut-brain axis due to efficient digestion and absorption". Journal of Gastroenterology. 48 (4): 442–51. doi:10.1007/s00535-013-0778-1. PMC 3698427. PMID 23463402.

- Fleming A (9 April 2013). "Umami: why the fifth taste is so important". The Guardian. London, UK. Retrieved 18 February 2017.

- Blake H (9 February 2010). "Umami in a tube: 'fifth taste' goes on sale in supermarkets". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 10 February 2011.

- Jufresa L (February 16, 2015). Umami (Mapa de las lenguas) (Ebook) (in Spanish). Spain: Penguin Random House Grupo Editorial México. ISBN 978-607-31-2817-9.

- Mouritsen JD, Drotner J, Styrbæk K, Mouritsen OG (April 2014). Umami: Unlocking the Secrets of the Fifth Taste (Ebook). United States: Columbia University Press. pp. 35–36. doi:10.7312/mour16890. ISBN 978-0-231-53758-2. JSTOR 10.7312/mour16890.

- Nelson G, Chandrashekar J, Hoon MA, Feng L, Zhao G, Ryba NJ, Zuker CS (March 2002). "An amino-acid taste receptor". Nature. 416 (6877): 199–202. Bibcode:2002Natur.416..199N. doi:10.1038/nature726. PMID 11894099. S2CID 1730089.

- Delay ER, Beaver AJ, Wagner KA, Stapleton JR, Harbaugh JO, Catron KD, Roper SD (October 2000). "Taste preference synergy between glutamate receptor agonists and inosine monophosphate in rats". Chemical Senses. 25 (5): 507–15. doi:10.1093/chemse/25.5.507. PMID 11015322.

- Chaudhari N, Landin AM, Roper SD (February 2000). "A metabotropic glutamate receptor variant functions as a taste receptor". Nature Neuroscience. 3 (2): 113–9. doi:10.1038/72053. PMID 10649565. S2CID 16650588.

- "Umami taste receptor identified". Nature Neuroscience (Press release). February 2000. Archived from the original on 2013-03-05.

- Krulwich R (5 November 2007). "Sweet, Sour, Salty, Bitter ... and Umami". National Public Radio (NPR), USA.

- Shugart, Helene A. (2008). "Sumptuous Texts: Consuming "Otherness" in the Food Film Genre". Critical Studies in Media Communication. 25 (1): 68–90. doi:10.1080/15295030701849928. S2CID 145672719.

- "You first eat with your eyes". Archived from the original on 29 May 2015. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- Food Texture, Andrew J. Rosenthal

- Rosenthal, Andrew J (1999). Food Texture: Measurement and Perception. ISBN 978-0-8342-1238-1. Archived from the original on 2021-09-22. Retrieved 2020-11-11.

- Mead, 11–19

- McGee, 142–43.

- McGee, 202–06

- Davidson, 786–87.

- Robuchon, 224.

- Davidson, 656

- McGee Chapter 14.

- Mead, 11–19.

- McGee

- Campbell, 312.

- McGee, 784.

- Davidson, 782–83

- McGee, 539,784.

- McGee, 771–91

- Davidson, 356.

- Asado Argentina

- "Definition of 'restaurant'". collinsdictionary.com. Archived from the original on 2018-10-06. Retrieved 2018-10-06.

- "restaurant (n.)". etymonline.com. Archived from the original on 2018-10-06. Retrieved 2018-10-06.

- "The History of the Restaurant". digital.library.unlv.edu. Archived from the original on 2018-10-06. Retrieved 2018-10-06.

- Davidson, 660–61.

- Bee Wilson (3 March 2013). "Pompeii exhibition: the food and drink of the ancient Roman cities". telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on 27 March 2013.

- "A Culinary Legacy from the Song Dynasty". Shanghai Daily. 11 September 2014 – via ProQuest.

- United States Department of Agriculture

- Mason

- Messer, 53–91.

- Boelee, E. (Ed) Ecosystems for water and food security Archived 23 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine, 2011, IWMI, UNEP

- Aguilera, 1–3.

- Miguel, 3.

- Jango-Cohen

- Hannaford

- The Economic Research Service of the USDA

- Regmi

- CIA World Factbook

- World Trade Organization, The Uruguay Round

- Van den Bossche

- Smith, 501–03.

- Benson

- Humphery

- Magdoff, Fred (Ed.) "[T]he farmer's share of the food dollar (after paying for input costs) has steadily declined from about 40 percent in 1910 to less than 10 percent in 1990."

- Roser, Max; Ritchie, Hannah (2013-10-08). "Food Prices". Our World in Data.

- Amadeo, Kimberly. "5 Causes of High Food Prices". The Balance. Retrieved 2020-09-19.

- Abbott, Philip C.; Hurt, Christopher; Tyner, Wallace E., eds. (2008). What's Driving Food Prices?. Issue Report.

- Savary, Serge; Ficke, Andrea; Aubertot, Jean-Noël; Hollier, Clayton (2012-12-01). "Crop losses due to diseases and their implications for global food production losses and food security". Food Security. 4 (4): 519–537. doi:10.1007/s12571-012-0200-5. ISSN 1876-4525. S2CID 3335739.

- "Hedge funds accused of gambling with lives of the poorest as food prices soar". The Guardian. 2010-07-18. Retrieved 2020-09-19.

- "Food speculation". Global Justice Now. 2014-12-09. Retrieved 2020-09-19.

- Spratt, S. (2013). "Food price volatility and financial speculation". FAC Working Paper 47. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.304.5228.

- "Food Price Explained". Futures Fundamentals. Retrieved 2020-09-19.

- Bellemare, Marc F. (2015). "Rising Food Prices, Food Price Volatility, and Social Unrest". American Journal of Agricultural Economics. 97 (1): 1–21. doi:10.1093/ajae/aau038. hdl:10.1093/ajae/aau038. ISSN 1467-8276. S2CID 34238445.

- Perez, Ines. "Climate Change and Rising Food Prices Heightened Arab Spring". Scientific American. Retrieved 2020-09-19.

- Winecoff, Ore Koren, W. Kindred. "Food Price Spikes and Social Unrest: The Dark Side of the Fed's Crisis-Fighting". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 2020-09-19.

- Darmon, Nicole; Drewnowski, Adam (2015-10-01). "Contribution of food prices and diet cost to socioeconomic disparities in diet quality and health: a systematic review and analysis". Nutrition Reviews. 73 (10): 643–660. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuv027. ISSN 0029-6643. PMC 4586446. PMID 26307238.

- Darnton-Hill, Ian; Cogill, Bruce (2010-01-01). "Maternal and Young Child Nutrition Adversely Affected by External Shocks Such As Increasing Global Food Prices". The Journal of Nutrition. 140 (1): 162S–169S. doi:10.3945/jn.109.111682. ISSN 0022-3166. PMID 19939995.

- "Climate Change: The Unseen Force Behind Rising Food Prices?". World Watch Institute. 2013. Archived from the original on 17 July 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- The State of Food and Agriculture 2019. Moving forward on food loss and waste reduction, In brief. Rome: FAO. 2019. p. 18.

- "Summary Findings Food Price Outlook, 2022 and 2023". USDA.

- Gunther Capelle-Blancard,Dramane Coulibaly (2011). "Index trading and agricultural commodity prices: A panel Granger causality analysis". Économie Internationale. 2–3 (126): 51–72.

- Smith, Adam (1977) [1776]. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-76374-9.

- "Food speculation". Global Justice Now. 2014-12-09. Retrieved 2019-08-21.

- Vidal, John (2011-01-23). "Food speculation: aFood speculation: 'People die from hunger while banks make a killing on food'". the Guardian. Retrieved 2019-08-21.

- Islam, M. Shahidul. "Of Agflation and Agriculture: Time to Fix the Structural Problems" (PDF). National University of Singapore. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- Anna Chadwick (2015). Food Commodity Speculation, Hunger, and the Global Food Crisis: Whither Regulation (Thesis). London School of Economics and Political Science. S2CID 155654460.

- GHOSH, JAYATI (2010). "The Unnatural Coupling: Food and Global Finance". Journal of Agrarian Change. Wiley. 10 (1): 72–86. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0366.2009.00249.x. ISSN 1471-0358.

- World Health Organization

- Howe, 353–72

- "The Food Waste Fiasco: You Have to See it to Believe it". Rob Greenfield. 2014-10-06. Retrieved 2020-09-22.

- Gustavsson, Jenny. Global food losses and food waste : extent, causes and prevention : study conducted for the International Congress "Save Food!" at Interpack 2011 Düsseldorf, Germany. OCLC 1126211917.

- "UN Calls for Action to End Food Waste Culture - October 4, 2021". Daily News Brief. 2021-10-04. Retrieved 2021-10-04.