French Directory

The Directory (also called Directorate, French: le Directoire) was the governing five-member committee in the French First Republic from 2 November 1795 until 9 November 1799, when it was overthrown by Napoleon Bonaparte in the Coup of 18 Brumaire and replaced by the Consulate. Directoire is the name of the final four years of the French Revolution. Mainstream historiography[1] also uses the term in reference to the period from the dissolution of the National Convention on 26 October 1795 (4 Brumaire) to Napoleon's coup d’état.

| Directory of the First French Republic | |

|---|---|

| Première République Directoire (French) | |

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Style | "His Excellency" |

| Type | Directorial government |

| Status | Disestablished |

| Abbreviation | The Directory |

| Seat | Luxembourg Palace, Paris |

| Appointer | Legislative Body (Council of Five Hundred and Council of Ancients) |

| Term length | Variable by election date |

| Constituting instrument | Constitution of the Year III |

| Precursor | Committee of Public Safety |

| Formation | 2 November 1795 |

| Abolished | 10 November 1799 |

| Succession | Executive Consulate |

| History of France |

|---|

|

| Topics |

| Timeline |

|

|

The Directory was continually at war with foreign coalitions, including Britain, Austria, Prussia, the Kingdom of Naples, Russia and the Ottoman Empire. It annexed Belgium and the left bank of the Rhine, while Bonaparte conquered a large part of Italy. The Directory established 196 short-lived sister republics in Italy, Switzerland and the Netherlands. The conquered cities and states were required to send France huge amounts of money, as well as art treasures, which were used to fill the new Louvre museum in Paris. An army led by Bonaparte tried to conquer Egypt and marched as far as Saint-Jean-d'Acre in Syria. The Directory defeated a resurgence of the War in the Vendée, the royalist-led civil war in the Vendée region, but failed in its venture to support the Irish Rebellion of 1798 and create an Irish Republic.

The French economy was in continual crisis during the Directory. At the beginning, the treasury was empty; the paper money, the Assignat, had fallen to a fraction of its value, and prices soared. The Directory stopped printing assignats and restored the value of the money, but this caused a new crisis; prices and wages fell, and economic activity slowed to a standstill.

In its first two years, the Directory concentrated on ending the excesses of the Jacobin Reign of Terror; mass executions stopped, and measures taken against exiled priests and royalists were relaxed. The Jacobin political club was closed and the government crushed an armed uprising planned by the Jacobins and an early socialist revolutionary, François-Noël Babeuf, known as "Gracchus Babeuf". But after the discovery of a royalist conspiracy including a prominent general, Jean-Charles Pichegru, the Jacobins took charge of the new Councils and hardened the measures against the Church and émigrés. They took two additional seats in the Directory, hopelessly dividing it.

In 1799, after several defeats, French victories in the Netherlands and Switzerland restored the French military position, but the Directory had lost all the political factions' support. Bonaparte returned from Egypt in October, and was engaged by Abbé Sieyès and others to carry out a parliamentary coup d'état on 8–9 November 1799. The coup abolished the Directory and replaced it with the French Consulate led by Bonaparte.

Background

The period known as the Reign of Terror began as a way of harnessing revolutionary fervour, but quickly degenerated into the settlement of personal grievances. On 17 September 1793, the Law of Suspects authorised the arrest of any suspected "enemies of freedom"; on 10 October, the National Convention recognised the Committee of Public Safety under Maximilien Robespierre as the supreme authority, and suspended the Constitution until "peace was achieved".[2]

According to archival records, from September 1793 to July 1794 some 16,600 people were executed on charges of counter-revolutionary activity; another 40,000 may have been summarily executed or died awaiting trial.[3] At its peak, the slightest hint of counter-revolutionary thoughts could place one under suspicion, and even his supporters began to fear their own survival depended on removing Robespierre. On 27 July, he and his allies were arrested and executed the next day.[4]

In July 1794, the Convention established a committee to draft what became the 1795 Constitution. Largely designed by Pierre Daunou and Boissy d'Anglas, it established a bicameral legislature, intended to slow down the legislative process, ending the wild swings of policy under the previous unicameral systems. Deputies were chosen by indirect election, a total franchise of around 5 million voting in primaries for 30,000 electors, or 0.5% of the population. Since they were also subject to stringent property qualification, it guaranteed the return of conservative or moderate deputies.[5]

It created a legislature consisting of the Council of 500, responsible for drafting legislation, and Council of Ancients, an upper house containing 250 men over the age of 40, who would review and approve it. Executive power was in the hands of five Directors, selected by the Council of Ancients from a list provided by the lower house, with a five-year mandate. This was intended to prevent executive power being concentrated in the hands of one man.[5]

D'Anglas wrote to the Convention:

We propose to you to compose an executive power of five members, renewed with one new member each year, called the Directory. This executive will have a force concentrated enough that it will be swift and firm, but divided enough to make it impossible for any member to even consider becoming a tyrant. A single chief would be dangerous. Each member will preside for three months; he will have during this time the signature and seal of the head of state. By the slow and gradual replacement of members of the Directory, you will preserve the advantages of order and continuity and will have the advantages of unity without the inconveniences.[6]

Drafting the new Constitution

The 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen was attached as a preamble, declaring "the Rights of Man in society are liberty, equality, security, and property".[7] It guaranteed freedom of religion, freedom of the press, and freedom of labour, but forbade armed assemblies and even public meetings of political societies. Only individuals or public authorities could tender petitions.

The judicial system was reformed, and judges were given short terms of office: two years for justices of the peace, five for judges of department tribunals. They were elected, and could be re-elected, to assure their independence from the other branches of government.

The new legislature had two houses, a Council of Five Hundred and a Council of Ancients with two hundred fifty members. Electoral assemblies in each canton of France, which brought together a total of thirty thousand qualified electors, chose representatives to an electoral assembly in each department, which then elected the members of both houses. The members of this legislature had a term of three years, with one-third of the members renewed every year. The Ancients could not initiate new laws, but could veto those proposed by the Council of Five Hundred.

The Constitution established a unique kind of executive, a five-man Directory chosen by the legislature.[8][9] It required the Council of Five Hundred to prepare, by secret ballot, a list of candidates for the Directory. The Council of Ancients then chose, again by secret ballot, the Directors from that provided list. The Constitution required that Directors be at least forty years old. To assure gradual but continual change, one Director, chosen by lot, was replaced each year. Ministers for the various departments of State aided the Directors. These ministers did not form a council or cabinet and had no general powers of government.

The new Constitution sought to create a separation of powers; the Directors had no voice in legislation or taxation, nor could Directors or Ministers sit in either house. To assure that the Directors would have some independence, each would be elected by one portion of the legislature, and they could not be removed by the legislature unless they violated the law.[6]

Under the new Constitution of 1795, to be eligible to vote in the elections for the Councils, voters were required to meet certain minimum property and residency standards. In towns with over six thousand population, they had to own or rent a property with a revenue equal to the standard income for at least one hundred fifty or two hundred days of work, and to have lived in their residence for at least a year. This ruled out a large part of the French population.

The greatest victim under the new system was the City of Paris, which had dominated events in the first part of the Revolution. On 24 August 1794, the committees of the sections of Paris, bastions of the Jacobins which had provided most of the manpower for demonstrations and invasions of the Convention, were abolished. Shortly afterwards, on 31 August, the municipality of Paris, which had been the domain of Danton and Robespierre, was abolished, and the city placed under direct control of the national government. When the Law of 19 Vendémiaire Year IV (11 October 1795), in application of the new Constitution, created the first twelve arrondissements of Paris, it established twelve new committees, one for each arrondissement. The city became a new department, the department of the Seine, replacing the former department of Paris created in 1790.[10][11]

Political developments (July 1794 – March 1795)

Meanwhile, the leaders of the still ruling National Convention tried to meet challenges from both neo-Jacobins on the left and royalists on the right. On 21 September 1794, the remains of Jean-Paul Marat, whose furious articles had promoted the Reign of Terror, were placed with great ceremony in the Panthéon, while on the same day, the moderate Convention member Merlin de Thionville described the Jacobins as "A hangout of outlaws" and the "knights of the guillotine". Young men known as Muscadins, largely from middle-class families, attacked the Jacobin and radical clubs. The new freedom of the press saw the appearance of a host of new newspapers and pamphlets from the left and the right, such as the royalist L'Orateur du peuple edited by Stanislas Fréron, an extreme Jacobin who had moved to the extreme right, and at the opposite end of the spectrum, the Tribun du peuple, edited by Gracchus Babeuf, a former priest who advocated an early version of socialism. On 5 February 1795, the semi-official newspaper Le Moniteur Universel (Le Moniteur) attacked Marat for encouraging the bloody extremes of the Reign of Terror. Marat's remains were removed from the Panthéon two days later.[12] The surviving Girondin deputies, whose leaders had been executed during the Reign of Terror, were brought back into the Convention on 8 March 1795.

The Convention tried to bring a peaceful end to the Catholic and royalist uprising in the Vendée. The Convention signed an amnesty agreement, promising to recognize the freedom of religion and allowing territorial guards to keep their weapons if the Vendéens would end their revolt. On a proposal from Boissy d'Anglas, on 21 February 1795 the Convention formally proclaimed the freedom of religion and the separation of church and state.[12]

Foreign policy

Between July 1794 and the October 1795 elections for the new-style Parliament, the government tried to obtain international peace treaties and secure French gains. In January 1795 General Pichegru took advantage of an extremely cold winter and invaded the Dutch Republic. He captured Utrecht on 18 January, and on 14 February units of French cavalry captured the Dutch fleet, which was trapped in the ice at Den Helder. The Dutch government asked for peace, conceding Dutch Flanders, Maastricht and Venlo to France. On 9 February, after a French offensive in the Alps, the Grand Duke of Tuscany signed a treaty with France. Soon afterwards, on 5 April, France signed a peace treaty, the Peace of Basel, with Prussia, where King Frederick William II was tired of the war; Prussia recognized the French occupation of the western bank of the Rhine. On 22 July 1795, a peace agreement, the "Treaty of Basel", was signed with Spain, where the French army had marched as far as Bilbao. By the time the Directory was chosen, the coalition against France was reduced to Britain and Austria, which hoped that Russia might be brought in on its side.

Failed Jacobin coup (May 1795) and rebellion in Brittany (June–July)

On 20 May 1795 (1 Prairial Year III), the Jacobins attempted to seize power in Paris. Following the model of Danton's seizure of the National Assembly in June 1792, a mob of sans-culottes invaded the meeting hall of the Convention at the Tuileries, killed one deputy, and demanded that a new government be formed. This time the army moved swiftly to clear the hall. Several deputies who had taken the side of the invaders were arrested. The uprising continued the following day, as the sans-culottes seized the Hôtel de Ville as they had done in earlier uprisings, but with little effect; crowds did not move to support them. On the third day, 22 May, the army moved into and occupied the working-class neighborhood of the Faubourg Saint-Antoine. The sans-culottes were disarmed and their leaders were arrested. In the following days the surviving members of the Committee of Public Safety, the committee that had been led by Robespierre, were arrested, with the exception of Carnot and two others. Six of the deputies who had participated in the uprising and had been sentenced to death committed suicide before they were taken to the guillotine.[13]

On 23 June 1795, the Chouans, royalist and Catholic rebels in Brittany, formed an army of 14,000 men near Quiberon. With the assistance of the British navy, a force of two thousand royalists was landed at Quiberon. The French army under General Hoche reacted swiftly, forcing the royalists to take refuge on the peninsula and then to withdraw. They surrendered on 21 July; 748 of the rebels were executed by firing squad.[14]

Adoption of the new Constitution

The new Constitution of the Year III was presented to the Convention and debated between 4 July – 17 August 1795, and was formally adopted on 22 August 1795. It was a long document, with 377 articles, compared with 124 in the first French Constitution of 1793. Even before it took effect, however, the members of the Convention took measures to assure they would still have dominance in the legislature over the government. They required that in the first elections, two hundred and fifty new deputies would be elected, while five hundred members of the old Convention would remain in place until the next elections. A national referendum of eligible voters was then held. The total number of voters was low; of five million eligible voters, 1,057,390 electors approved the Constitution, and 49,978 opposed it. The proposal that two thirds of members of the old Convention should remain in place was approved by a much smaller margin, 205,498 to 108,754.[15]

October 1795 royalist rebellion

The new Constitution of the Year III was officially proclaimed in force on 23 September 1795, but the new Councils had not yet been elected, and the Directors had not yet been chosen. The leaders of the royalists and constitutional monarchists chose this moment to try to seize power. They saw that the vote in favor of the new Constitution was hardly overwhelming. Paris voters were particularly hostile to the idea of keeping two-thirds of the old members of the Convention in the new Councils. A central committee was formed, with members from the wealthier neighborhoods of Paris, and they began planning a march on the center of the city and on the Tuileries, where the Convention still met.

The members of the Convention, very much experienced with conspiracies, were well aware that the planning was underway. A group of five republican deputies, led by Paul Barras, had already formed an unofficial directory, in anticipation of the creation of the real one. They were concerned about the national guard members from western Paris, and were unsure about the military commander of Paris, General Menou. Barras decided to turn to military commanders in his entourage who were known republicans, particularly Bonaparte, whom he had known when Bonaparte was successfully fighting the British in Toulon. Bonaparte, at this point a general of second rank in the Army of the Interior, was ordered to defend the government buildings on the right bank.

The armed royalist insurgents planned a march in two columns along both the right bank and left bank of the Seine toward the Tuileries. There on 5 October 1795, the royalists were met by the artillery of sous-lieutenant Joachim Murat at the Sablons and by Bonaparte's soldiers and artillery in front of the church of Saint-Roch. Over the next two hours, the "whiff of grapeshot" of Bonaparte's cannons and gunfire of his soldiers brutally mowed down advancing columns, killing some four hundred insurgents, and ending the rebellion. Bonaparte was promoted to General of Division on 16 October, and General in Chief of the Army of the Interior on 26 October. It was the last uprising to take place in Paris during the French Revolution.[16]

History

Directory takes charge

Between 12 and 21 October 1795, immediately after the suppression of royalist uprising in Paris, the elections for the new Councils decreed by the new Constitution took place. 379 members of the old Convention, for the most part moderate republicans, were elected to the new legislature. To assure that the Directory did not abandon the Revolution entirely, the Council required that all of the members of the Directory be former members of the Convention and regicides, those who had voted for the execution of Louis XVI.

Due to the rules established by the Convention, a majority of members of the new legislature, 381 of 741 deputies, had served in the Convention and were ardent republicans, but a large part of the new deputies elected were royalists, 118 versus 11 from the left. The members of the upper house, the Council of Ancients, were chosen by lot from among all of the deputies.

On 31 October 1795, the Council of Ancients chose the first Directory from a list of candidates submitted by the Council of Five Hundred. One person elected, the Abbé Sieyès, refused to take the position, saying it didn't suit his interests or personality. A new member, Lazare Carnot, was elected in his place.[17]

The members elected to the Directory were the following:

- Paul François Jean Nicolas, vicomte de Barras, a member of a minor noble family from Provence, Barras had been a revolutionary envoy to Toulon, where he met the young Bonaparte, and arranged his promotion to captain. Barras had been removed from the Committee of Public Safety by Robespierre. Fearing for his life, Barras had helped organize the downfall of Robespierre. An expert at political intrigue, Barras became the dominant figure in the Directory. His leading opponent in the Directory, Carnot, described him as "without faith and without morals... in politics, without character and without resolution... He has all the tastes of an opulent prince, generous, magnificent and dissipated."[18]

- Louis Marie de La Révellière-Lépeaux was a fierce republican and anti-Catholic, who had proposed to execute Louis XVI after the flight to Varennes. He promoted the establishment of a new religion, theophilanthropy, to replace Christianity.

- Jean-François Rewbell had an expertise in foreign relations, and was a close ally of Paul Barras. He was a firm moderate republican who had voted for the death of the King but had also opposed Robespierre and the extreme Jacobins. He was an opponent of the Catholic church and a proponent of individual liberties.

- Étienne-François Le Tourneur was a former captain of engineers, and a specialist in military and naval affairs. He was a close ally within the Directory of Carnot.

- Lazare Nicolas Marguerite Carnot: when the Abbé Sieyés was elected by the Ancients, but refused the position, his place was taken by Carnot. Carnot was an army captain at the beginning of the Revolution, and when elected to the Convention became a member of the commission of military affairs, as well as a vocal opponent of Robespierre. He was an energetic and efficient manager, who restructured the French military and helped it achieve its first successes, earning him the title of "The Organizer of the Victory." Napoleon, who later made Carnot his Minister of War, described him as "a hard worker, sincere in everything, but without intrigues, and easy to fool."[19]

The following day, the members of the new government took over their offices in the Luxembourg Palace, which had previously been occupied by the Committee of Public Safety. Nothing had been prepared, and the rooms had no furniture: they managed to find firewood to heat the room, and a table in order to work. Each member took charge of a particular sector: Rewbell diplomacy; Carnot and Le Tourneur military affairs, La Révellière-Lépeaux religion and public instruction, and Barras internal affairs.

The Council of Ancients was attributed the building at the Tuileries Palace formerly occupied by the Convention, while the Council of Five Hundred deliberated in the Salle du Manège, the former riding school west of the palace in the Tuileries Garden. One of the early decisions of the new parliament was to designate uniforms for both houses: the Five Hundred wore long white robes with a blue belt, a scarlet cloak and a hat of blue velour, while members of the Ancients wore a robe of blue-violet, a scarlet sash, a white mantle, and a violet hat. [20]

Gallery

Paul Barras (here in the ceremonial dress of a Director) was a master of political intrigue

Paul Barras (here in the ceremonial dress of a Director) was a master of political intrigue Louis Marie de La Révellière-Lépeaux

Louis Marie de La Révellière-Lépeaux Jean-François Rewbell

Jean-François Rewbell Étienne-François Le Tourneur

Étienne-François Le Tourneur Lazare Carnot, a brilliant organizer and mathematician but poor intriguer, was the enemy of Barras

Lazare Carnot, a brilliant organizer and mathematician but poor intriguer, was the enemy of Barras

Finance and economy

The new Director overseeing financial affairs, La Réveillière-Lépeaux, gave a succinct description of the financial state of France when the Directory took power: "The national Treasury was completely empty; not a single sou remained. The assignats were almost worthless; the little value which remained drained away each day with accelerated speed. One could not print enough money in one night to meet the most pressing needs of the next day.... The public revenues were nonexistent; citizens had lost the habit of paying taxes. [...] All public credit was dead and all confidence lost. [...] The depreciation of the assignats, the frightening speed of the fall, reduced the salary of all public employees and functionaries to a value which was purely nominal."[21]

The drop in value in the money was accompanied by extraordinary inflation. The Louis d'or (gold coin), which was worth 2,000₶. in paper money at the beginning of the Directory, increased to 3,000₶. and then 5,000₶. The price of a liter of wine increased from 2₶.10s. in October 1795 to 10₶. and then 30₶. A measure of flour worth 2₶. in 1790 was worth 225₶. in October 1794.[21]

The new government continued to print assignats, which were based on the value of property confiscated from the Church and the aristocracy, but it could not print them fast enough; even when it printed one hundred million in a day, it covered only one-third of the government's needs. To fill the treasury, the Directory resorted in December 1795 to a forced loan of 600 million-₶. from wealthy citizens, who were required to pay between 50₶. and 6,000₶. each.

To fight inflation, the government began minting more coins of gold and silver, which had real value; the government had little gold but large silver reserves, largely in the form of silverware, candlesticks and other objects confiscated from the churches and the nobility. It minted 72 million écus, and when this silver supply ran low, it obtained much more gold and silver through military campaigns outside of France, particularly from Bonaparte's army in Italy. Bonaparte demanded gold or silver from each city he conquered, threatening to destroy the cities if they did not pay.

These measures reduced the rate of inflation. On 19 February 1796, the government held a ceremony in the Place Vendôme to destroy the printing presses which had been used to produce huge quantities of assignats. This success produced a new problem: the country was still flooded with more than two billion four hundred million (2.400.000.000) assignats, claims on confiscated properties, which now had some value. Those who held assignats were able to exchange them for state mandates, which they could use to buy châteaux, church buildings and other biens nationaux (state property) at extremely reduced prices. Speculation became rampant, and property in Paris and other cities could change hands several times a day.

Another major problem faced by the Directory was the enormous public debt, the same problem that had led to the Revolution in the first place. In September–December 1797, the Directory attacked this problem by declaring bankruptcy on two-thirds of the debt, but assured payment on the other third. This resulted in the ruin of those who held large quantities of government bonds, but stabilized the currency. To keep the treasury full, the Directory also imposed new taxes on property owners, based on the number of fireplaces and chimneys, and later on the number of windows, of their residences. It refrained from adding more taxes on wine and salt, which had helped cause the 1789 revolution, but added new taxes on gold and silver objects, playing cards, tobacco, and other luxury products. Through these means, the Directory brought about a relative stability of finances which continued through the Directory and Consulate. [22]

Food supply

The food supply for the population, and particularly for the Parisians, was a major economic and political problem before and during the Revolution; it had led to food riots in Paris and attacks on the Convention. To assure the supply of food to the sans-culottes in Paris, the base of support of the Jacobins, the Convention had strictly regulated grain distribution and set maximum prices for bread and other essential products. As the value of the currency dropped, the fixed prices soon did not cover the cost of production, and supplies dropped. The Convention was forced to abolish the maximum on 24 December 1794, but it continued to buy huge quantities of bread and meat which it distributed at low prices to the Parisians. This Paris food distribution cost a large part of the national budget, and was resented by the rest of the country, which did not have that benefit. By early 1796, the grain supply was supplemented by deliveries from Italy and even from Algeria. Despite the increased imports, the grain supply to Paris was not enough. The Ministry of the Interior reported on 23 March 1796 that there was only enough wheat to make bread for five days, and there were shortages of meat and firewood. The Directory was forced to resume deliveries of subsidized food to the very poor, the elderly, the sick, and government employees. The food shortages and high prices were one factor in the growth of discontent and the Gracchus Babeuf's uprising, the Conspiracy of the Equals, in 1796. The harvests were good in the following years and the food supplies improved considerably, but the supply was still precarious in the north, the west, the southeast, and the valley of the Seine.[23]

Babeuf's Conspiracy of the Equals

In 1795, the Directory faced a new threat from the left, from the followers of François Noël Babeuf, a talented political agitator who took the name Gracchus and was the organizer of what became known as the Conspiracy of the Equals. Babeuf had, since 1789, been drawn to the Agrarian Law, an agrarian reform preconized by the ancient Roman brothers, Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus, of sharing goods in common, as means of achieving economic equality. By the time of the fall of Robespierre, he had abandoned this as an impractical scheme and was moving towards a more complex plan.[24] Babeuf did not call for the abolition of private property, and wrote that peasants should own their own plots of land, but he advocated that all wealth should be shared equally: all citizens who were able would be required to work, and all would receive the same income. Babeuf did not believe that the mass of French citizens was ready for self-government; accordingly, he proposed a dictatorship under his leadership until the people were educated enough to take charge. "People!", Babeuf wrote. "Breathe, see, recognize your guide, your defender.... Your tribune presents himself with confidence."[25]

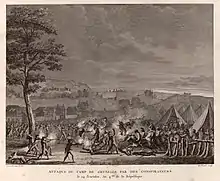

At first, Babeuf's following was small; the readers of his newspaper, Le Tribun du peuple ("The Tribune of the People"), were mostly middle-class far-left Jacobins who had been excluded from the new government. However, his popularity increased in the working-class of the capital with the drop in value of the assignats, which rapidly resulted in the decrease of wages and the rise of food prices. Beginning in October 1795, he allied himself with the most radical Jacobins, and on 29 March 1796 formed the Directoire secret des Égaux ("Secret Directory of Equals"), which proposed to "revolutionize the people" through pamphlets and placards, and eventually to overthrow the government. He formed an alliance of utopian socialists and radical Jacobins, including Félix Lepeletier, Pierre-Antoine Antonelle, Sylvain Marechal, Jean-Pierre-André Amar and Jean-Baptiste Robert Lindet. The Conspiracy of Equals was organized in a novel way: in the center was Babeuf and the Secret Directory, who hid their identities, and shared information with other members of the Conspiracy only via trusted intermediaries. This conspiratorial structure was later adopted by Marxist movements. Despite his precautions, the Directory infiltrated an agent into the conspiracy, and was fully informed of what he was doing.[26] Bonaparte, the newly named commander of the Army of the Interior, was ordered to close the Panthéon Club, the major meeting place for the Jacobins in Paris, which he did on 27 February 1796. The Directory took other measures to prevent an uprising; the Legion of Police (légion de police), a local police force dominated by Jacobins, was forced to become a part of the Army, and the Army organized a mobile column to patrol the neighborhoods and stop uprisings.[27]

Before Babeuf and his conspiracy could strike, he was betrayed by a police spy and arrested in his hiding place on 10 May 1796. Though he was a talented agitator, he was a very poor conspirator; with him in his hiding place were the complete records of the conspiracy, with all of the names of the conspirators. Despite this setback, the conspiracy went ahead with its plans. On the night of 9–10 September 1796, between 400 and 700 Jacobins went to the 21st Regiment of Dragoons (21e régiment de dragons) army camp at Grenelle and tried to incite an armed rebellion against the Convention. At the same time a column of militants was formed in the working-class neighborhoods of Paris to march on the Luxembourg Palace, headquarters of the Directory. Director Carnot had been informed the night before by the commander of the camp, and a unit of dragoons was ready. When the attack began at about ten o'clock, the dragoons appeared suddenly and charged. About twenty Jacobins were killed, and the others arrested. The column of militants, learning what had happened, disbanded in confusion. The widespread arrest of Babeuf's militants and Jacobins followed. The practice of arresting suspects at their homes at night, stopped after the downfall of Robespierre, was resumed on this occasion.

Despite his arrest, Babeuf, in jail, still felt he could negotiate with the government. He wrote to the Directory: "Citizen Directors, why don't you look above yourselves and treat with me as with an equal power? You have seen now the vast confidence of which I am the center... this view makes you tremble."[28] Several attempts were made by Babeuf's followers to free him from prison. He was finally moved to Vendôme for trial. The Directory did not tremble. The accused Jacobins were tried by military courts between 19 September and 27 October. Thirty Jacobins, including three former deputies of the Convention, were convicted and guillotined. Babeuf and his principal followers were tried in Vendôme between 20 February and 26 May 1797. The two principal leaders, Babeuf and Darthé, were convicted. They both attempted suicide, but failed and were guillotined on 27 May 1797. However, in the following months, the Directory and Councils gradually turned away from the royalist right and tried to find new allies on the left.[28][29][30]

War and Diplomacy (1796–1797)

The major preoccupation of the Directory during its existence was the war against the coalition of Britain and Austria. The military objective set by the Convention in October 1795 was to enlarge France to what were declared its natural limits: the Pyrenees, the Rhine and the Alps, the borders of Gaul at the time of the Roman Empire. In 1795, Prussia, Spain and the Dutch Republic quit the War of the First Coalition and made peace with France, but Great Britain refused to accept the French annexation of Belgium. Beside Britain and Austria, the only enemies remaining for France were the kingdom of Sardinia and several small Italian states. Austria proposed a European congress to settle borders, but the Directory refused, demanding direct negotiations with Austria instead. Under British pressure, Austria agreed to continue the war against France.[31]

Lazare Carnot, the Director who oversaw military affairs, planned a new campaign against Austria, using three armies: General Jourdan's Army of Sambre-et-Meuse on the Rhine and General Moreau's Army of the Rhine and Moselle on the Danube would march to Vienna and dictate a peace. A third army, the Army of Italy under General Bonaparte, who had risen in rank with spectacular speed due to his defense of the government from a royalist uprising, would carry out a diversionary operation against Austria in northern Italy. Jourdan's army captured Mayence and Frankfurt, but on 14 August 1796 was defeated by the Austrians at the Battle of Amberg and again on 3 September 1796 at the Battle of Würzburg, and had to retreat back to the Rhine. General Moreau, without the support of Jourdan, was also forced to retreat.

Italian campaign

The story was very different in Italy. Bonaparte, though he was only twenty-eight years old, was named commander of the Army of Italy on 2 March 1796, through the influence of Barras, his patron in the Directory. Bonaparte faced the combined armies of Austria and Sardinia, which numbered seventy thousand men. Bonaparte slipped his army between them and defeated them in a series of battles, culminating at the Battle of Mondovi where he defeated the Sardinians on 22 April 1796, and the Battle of Lodi, where he defeated the Austrians on 10 May. The king of Sardinia and Savoy was forced to make peace in May 1796 and ceded Nice and Savoy to France.

At the end of 1796, Austria sent two new armies to Italy to expel Bonaparte, but Bonaparte outmaneuvered them both, winning a first victory at the Battle of Arcole on 17 November 1796, then at the Battle of Rivoli on 14 January 1797. He forced Austria to sign the Treaty of Campo Formio (October 1797), whereby the emperor ceded Lombardy and the Austrian Netherlands to the French Republic in exchange for Venice and urged the Diet to surrender the lands beyond the Rhine.[32]

Spanish alliance

The Directory was eager to form a coalition with Spain to block British commerce with the continent and to close the Mediterranean Sea to British ships. By the Treaty of San Ildefonso, concluded in August 1796, Spain became the ally of France, and on 5 October, it declared war on Britain. The British fleet under Admiral Jervis defeated the Spanish fleet at the Cape St Vincent, keeping the Mediterranean open to British ships, but the United Kingdom was brought into such extreme peril by the mutinies in its fleet that it offered to acknowledge the French conquest of the Netherlands and to restore the French colonies.

Irish Misadventure

The Directory also sought a new way to strike British interests and to repay the 1707–1800 Kingdom of Great Britain for the support it gave to royalist insurgents in Brittany, France. A French fleet of 44 vessels departed Brest on 15 December 1796, carrying an expeditionary force of 14,000 soldiers, led by General Hoche to Ireland, where they hoped to join forces with Irish rebels to expel the British from the 1542–1800 Kingdom of Ireland. However, the fleet was separated by storms off the Irish coast and, being unable to land on Ireland, had to return to home port with 31 vessels and 12,000 surviving soldiers.

Rise of the royalists and coup d'état (1797)

The first elections held after the formation of the Directory were held in March and April 1797, in order to replace one-third of the members of the Councils. The elections were a crushing defeat for the old members of the Convention; 205 of the 216 were defeated. Only eleven former deputies from the Convention were reelected, several of whom were royalists.[33] The elections were a triumph for the royalists, particularly in the south and in the west; after the elections there were about 160 royalist deputies, divided between those who favored a return to an absolute monarchy, and those who wished a constitutional monarchy on the British model. The constitutional monarchists elected to the Council included Pierre Samuel du Pont de Nemours, who later emigrated to the United States with his family, and whose son, Éleuthère Irénée du Pont, founded the "E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company", now known as DuPont. In Paris and other large cities, the candidates of the left dominated. General Jean-Charles Pichegru, a former Jacobin and ordinary soldier who had become one of the most successful generals of the Revolution, was elected president of the new Council of Five Hundred. François Barbé-Marbois, a diplomat and future negotiator of the sale of Louisiana to the United States, was elected president of the Council of Ancients.

Royalism was not strictly legal, and deputies could not announce themselves as such, but royalist newspapers and pamphlets soon appeared, there were pro-monarchy demonstrations in theaters, and royalists wore identifying clothing items, such as black velvet collars, in show of mourning for the execution of Louis XVI. The parliamentary royalists demanded changes in the government fiscal policies, and a more tolerant position toward religion. During the Convention, churches had been closed and priests required to take an oath to the government. Priests who had refused to take the oath were expelled from the country, on pain of the death penalty if they returned. Under the Directory, many priests had quietly returned, and many churches around the country had re-opened and were discreetly holding services. When the Directory proposed moving the ashes of the celebrated mathematician and philosopher René Descartes to the Panthéon, one deputy, Louis-Sébastien Mercier, a former Girondin and opponent of the Jacobins, protested that the ideas of Descartes had inspired the Reign of Terror of the Revolution and destroyed religion in France. Descartes' ashes were not moved.[34] Émigrés who had left during the Revolution had been threatened by the Convention with the death penalty if they returned; now, under the Directory, they quietly began to return.[35]

Parallel with the parliamentary royalists, but not directly connected with them, a clandestine network of royalists existed, whose objective was to place Louis XVIII, then in exile in Germany, on the French throne. They were funded largely by Britain, through the offices of William Wickham, the British spymaster who had his headquarters in Switzerland. These networks were too divided and too closely watched by the police to have much effect on politics. However, Wickham did make one contact that proved to have a decisive effect on French politics: through an intermediary, he had held negotiations with General Pichegru, then commander of the Army of the Rhine.[36]

The Directory itself was divided. Carnot, Letourneur and La Révellière Lépeaux were not royalists, but favored a more moderate government, more tolerant of religion. Though Carnot himself had been a member of the Committee of Public Safety led by Robespierre, he declared that the Jacobins were ungovernable, that the Revolution could not go on forever, and that it was time to end it. A new member, François-Marie, marquis de Barthélemy, a diplomat, had joined the Directory; he was allied with Carnot. The royalists in the Councils immediately began to demand more power over the government and particularly over the finances, threatening the position of Barras.[37]

Barras, the consummate intriguer, won La Révellière Lépeaux over to his side, and began planning the downfall of the royalists. From letters taken from a captured royalist agent, he was aware of the contacts that General Pichegru made with the British and that he had been in contact with the exiled Louis XVIII. He presented this information to Carnot, and Carnot agreed to support his action against the Councils. General Hoche, the new Minister of War, was directed to march the Army of Sambre-et-Meuse through Paris on its way to Brest, on the pretext that they would be embarked for a new expedition to Ireland. Hoche himself resigned as Minister of War on 22 July. General Pierre Augereau, a close subordinate and ally of Bonaparte, and his troops arrived in Paris on 7 August, though it was a violation of the Constitution for soldiers to be within twelve leagues of the city without permission of the Councils. The royalist members of the Councils protested, but could do nothing to send them away.[38]

On 4 September 1797, with the army in place, the Coup d'état of 18 Fructidor, Year V was set in motion. General Augereau's soldiers arrested Pichegru, Barthélemy, and the leading royalist deputies of the Councils. The next day, the Directory annulled the elections of about two hundred deputies in 53 departments.[39] Sixty-five deputies were deported to Guiana, 42 royalist newspapers were closed, and 65 journalists and editors were deported. Carnot and Barthélemy were removed from the Directory. Carnot went into exile in Switzerland; he later returned and became, for a time, Bonaparte's minister of war. Barthélemy and Pichegru both were sent to exile in French Guiana (penal colony of Cayenne). In June 1798, they both escaped, and went first to the United States and then to England. During the Consulate, Pichegru returned secretly to Paris, where he was captured on 28 February 1804. He died in prison on 6 April 1804, either strangled or having committed suicide.

Second Directory and resurgence of the Jacobins

The coup was followed by a scattering of uprisings by royalists in Aix-en-Provence, Tarascon and other towns, particularly in the southwest and west. A commissioner of the Directory was assassinated in Lyon, and on 22 October counter-revolutionaries seized the city government of Carpentras for twenty-four hours. These brief uprisings served only to justify a wave of repression from the new government.[40]

With Carnot and Barthélemy gone from the Directory, and the royalists expelled from the Councils, the Jacobins were once again in control of the government. The two vacant places in the Directory were filled by Merlin de Douai, a lawyer who had helped write the Law of Suspects during the Reign of Terror; and François de Neufchâteau, a poet and expert in industry inland navigation, who served only a few months. Eight of the twelve Directors and ministers of the new government were regicides, who as deputies of the Convention had voted for the execution of Louis XVI, and were now determined to continue the Revolution.[41][42]

The central administration and city governments were quickly purged of suspected royalists. The next target was the wave of noble émigrés and priests who had begun to return to France. The Jacobins in the Councils demanded that the law of 1793 be enforced; émigrés were ordered to leave France within fifteen days. If they did not, they were to be judged by a military commission, and, on simple proof of their identity, were to be executed within twenty-four hours. Military commissions were established throughout the country to judge not only returning émigrés, but also rebels and conspirators. Between 4 September 1797 and the end of the Directory in 1799, 160 persons were condemned to death by the military tribunals, including 41 priests and several women.[43]

On 16 October 1797, the Council of Five Hundred considered a new law which banned political activities by nobles, who were to be considered as foreigners, and had to apply for naturalization in order to take part in politics. A certain number, listed by names, were to be banned permanently from political activity, were to have their property confiscated, and were to be required to leave immediately. The law called for certain exemptions for those in the government and military (Director Barras and General Bonaparte were both from minor noble families). In the end, resistance to the law was so great that it was not adopted.[44]

The Jacobin-dominated councils also demanded the deportation of priests who refused to take an oath to the government, and an oath declaring their hatred of royalty and anarchy. 267 priests were deported to the French penal colony of Cayenne in French Guiana, of whom 111 survived and returned to France. 920 were sent to a prison colony on the Île de Ré, and 120, a large part of them Belgians, to another colony on the Île d'Oléron.[45][46] The new government continued the anti-religious policy of the Convention. Several churches, including the cathedral Notre Dame de Paris and the church of Saint-Sulpice, were converted Theophilanthropic temples, a new religion based on the belief in the existence of God and the immortality of the human spirit. Religious observations were forbidden on Sunday; they were allowed only on the last day of the 10-day week (décade) of the French Republican Calendar.[47] Other churches remained closed, and were forbidden to ring their bells, although many religious services took place in secret in private homes. The National Guard was mobilized to search rural areas and forests for priests and nobles in hiding. As during the Reign of Terror, lists were prepared of suspects, who would be arrested in the event of attempted uprisings.[43]

The new Jacobin-dominated Directory and government also targeted the press. Newspaper publishers were required to submit copies of their publications to the police for official approval. On 17 December 1797, seventeen Paris newspapers were closed by order of the Directory. The Directory also imposed a substantial tax on all newspapers or magazines distributed by mail, although Jacobin publications, as well as scientific and art publications, were excluded. Books critical of the Jacobins were censored; Louis-Marie Prudhomme's six-volume Histoire générale et impartiale des erreurs, des fautes et des crimes commis pendant la Révolution française[48] ("General and impartial history of the errors, faults and crimes committed during the French Revolution") was seized by the police. The Directory also authorized the opening and reading of letters coming from outside of France.[49]

Despite all these security measures, there was a great increase in brigandage and robbery in the French countryside; travelers were frequently stopped on roads and robbed; the robberies were often blamed on royalist bands. On 18 January 1798, the Councils passed a new law against highwaymen and bandits, calling for them to be tried by military tribunals, and authorizing the death penalty for robbery or attempted robbery on the roads of France.[50]

The political repression and terror under the Directory were real, but they were on a much smaller scale than the Reign of Terror under Robespierre and the Convention, and the numbers of those repressed declined during the course of the Directory. After 1798, no further political prisoners were sent to French Guiana, and, in the final year of the Directory, only one person was executed for a political offense.[51]

Elections of 1798

In the spring of 1798, not only a new third of the legislature had to be chosen, but the places of the members expelled by the revolution of Fructidor had to be filled. 437 seats were open, out of 750. The elections took place between 9 and 18 April. The royalists had been disqualified, and the moderates were in disarray, while the radical Jacobins made a strong showing. Before the new deputies could take their seats, Barras and the other Directors, more moderate than the new Jacobins, organized a commission to review the elections, and disqualified many of the more extreme Jacobin candidates (Law of 22 Floréal Year VI), replacing them with moderates. They sent the list of candidates for Director to the Councils, excluding any radicals. François de Neufchåteau was chosen by a drawing of lots to leave the Directory and Barras proposed only moderate Jacobins to replace him: the choice fell on Jean-Baptiste Treilhard, a lawyer. These political maneuvers secured the power of the Directory, but widened further the gap between the moderate Directory and the radical Jacobin majority in the Councils.[52]

War and diplomacy (1798)

On 17 October 1797, General Bonaparte and the Austrians signed the Treaty of Campoformio. It was a triumph for France. France received the left bank of the Rhine as far south of Cologne, Belgium, and the islands in the Ionian Sea that had belonged to Venice. Austria in compensation was given the territories of Venice up to the Aegean Sea. In late November and December, he took part in negotiations with the Holy Roman Empire and Austria, at the Second Congress of Rastatt, to redraw the borders of Germany. He was then summoned back to Paris to take charge of an even more ambitious project, the invasion of Britain, which had been proposed by Director Carnot and General Hoche. But an eight-day inspection of the ports where the invasion fleet was being prepared convinced Bonaparte that the invasion had little chance of success: the ships were in poor condition, the crews poorly trained, and funds and logistics were lacking. He privately told his associate Marmont his view of the Directory: "Nothing can be done with these people. They don't understand anything of greatness. We need to go back to our projects for the East. It is only there that great results can be achieved."[53] The invasion of England was cancelled, and a less ambitious plan to support an Irish uprising was proposed instead (see below).

Sister Republics

The grand plan of the Directory in 1798, with the assistance of its armies, was the creation of "Sister Republics" in Europe which would share the same revolutionary values and same goals, and would be natural allies of France. In the Dutch Republic (Republic of the Seven United Netherlands), the French army installed the Batavian Republic with the same system of a Directory and two elected Councils. In Milan, the Cisalpine Republic was created, which was governed jointly by a Directory and Councils and by the French army. General Berthier, who had replaced Bonaparte as the commander of the Army of Italy, imitated the actions of the Directory in Paris, purging the new republic's legislature of members whom he considered too radical. The Ligurian Republic was formed in Genoa. Piedmont was also turned by the French army into a sister republic, the Piedmontese Republic. In Turin, King Charles-Emmanuel IV, (whose wife, Clotilde, was Louis XVI's youngest sister), fled French dominance and sailed, protected by the British fleet, to Sardinia. In Savoy, General Joubert did not bother to form a sister republic, he simply made the province a department of France.[54]

The Directory also directly attacked the authority of Pope Pius VI, who governed Rome and the Papal States surrounding it. Shortly after Christmas on 28 December 1797, anti-French riots took place in Rome, and a French Army brigadier general, Duphot, was assassinated. Pope Pius VI moved quickly and formally apologized to the Directory on 29 December 1797, but the Directory refused his apology. Instead, Berthier's troops entered Rome and occupied the city on 10 February 1798. Thus the Roman Republic was also proclaimed on 10 February 1798. Pius VI was arrested and confined in the Grand Duchy of Tuscany before being taken to France in 1799. The Vatican treasury of thirty million francs was sent to Paris, where it helped finance Bonaparte's expedition to Egypt, and five hundred cases of paintings, statues, and other art objects were sent to France and added to the collections of the Louvre.[55]

A French army under General Guillaume Brune occupied much of Switzerland. The Helvetian Republic was proclaimed on 12 April 1798. On 26 August 1798, Geneva was detached from the new republic and made part of France. The treasury of Bern was seized, and, like the treasury of the Vatican, was used to finance Bonaparte's expedition to Egypt.

The new military campaigns required thousands of additional soldiers. The Directory approved the first permanent law of conscription, which was unpopular in the countryside, and particularly in Belgium, which had formally become part of France. Riots and peasant uprisings took place in the Belgian countryside. Blaming the unrest on Belgian priests, French authorities ordered the arrest and deportation of several thousands of them.[56]

Bonaparte's expedition to Egypt (May 1798)

The idea of a French military expedition to Egypt had been proposed by Talleyrand in a memoir to the French Institute as early as 3 July 1797, and in a letter the following month from Talleyrand to Bonaparte. The Egyptian expedition had three objectives: to cut the shortest route from England to British India by occupying the Isthmus of Suez; to found a colony which could produce cotton and sugar cane, which were in short supply in France due to the British blockade; and to provide a base for a future French attack on British India. It also had several personal advantages for Bonaparte: it allowed him to keep a distance from the unpopular Directory, while at the same time staying in the public eye.[57]

The Directory itself was not enthusiastic about the idea, which would take its most successful general and his army far from Europe just at the time that a major new war was brewing. Director La Révellière-Lépeaux wrote: "The idea never came from the Directory or any of its members. The ambition and pride of Bonaparte could no longer support the idea of not being visible, and of being under the orders of the Directory."

The idea presented two other problems: Republican French policy was opposed to colonization, and France was not at war with the Ottoman Empire, to which Egypt belonged. Therefore, the expedition was given an additional scientific purpose: "to enlighten the world and to obtain new treasures for science." A large team of prominent scientists was added to the expedition; twenty-one mathematicians, three astronomers, four architects, thirteen naturalists and an equal number of geographers, plus painters, a pianist and the poet François-Auguste Parseval-Grandmaison.[58]

On 19 May 1798, two hundred ships carrying Bonaparte, and 35,000 men comprising the Armée d'Orient, most of them veterans of Bonaparte's Army of Italy, sailed from Toulon. The British fleet under Nelson, expecting a French expedition toward Constantinople, was not in position to stop them. The French fleet stopped briefly at Malta, capturing the island, the government of which offered little resistance. Bonaparte's army landed in the bay of Alexandria on 1 July, and captured that city on 2 July, with little opposition. He wrote a letter to the Pascha of Egypt, claiming that his purpose was to liberate Egypt from the tyranny of the Mamluks. His army marched across the desert, despite extreme heat, and defeated the Mameluks at the Battle of the Pyramids on 21 July 1798. A few days later, however, on 1 August, the British fleet under Admiral Nelson arrived off the coast; the French fleet was taken by surprise and destroyed in the Battle of the Nile. Only four French ships escaped. Bonaparte and his army were prisoners in Egypt.[59]

Failed uprising in Ireland (August 1798)

Another attempt to support an Irish uprising was made on 7 August 1798. A French fleet sailed from Rochefort-sur-Mer (Rochefort) carrying an expeditionary force led by General Jean Joseph Amable Humbert. The attack was intended to support an uprising of Irish nationalists led by Wolfe Tone. Tone had several meetings with Bonaparte in France to coordinate the timing, but the uprising within the Kingdom of Ireland began early and was suppressed on 14 July 1798 before the French fleet arrived. The French force landed at Killala, in northwest Ireland, on 22 August. It defeated British troops in two small engagements on 24 and 27 August, and Humbert declared the formation of an Irish Republic at Castlebar on 27 August, but the French forces were defeated at the Battle of Ballinamuck on 8 September 1798 by the troops of Lord Cornwallis, British Commander-in-chief in Ireland. A second part of the French expeditionary force, not knowing that the first had surrendered, left Brest on 16 September. It was intercepted by the British Navy in the bay of Donegal, and six of the French warships were captured.[60]

Quasi-War with the United States (1798–1799)

Tensions between the United States and France developed into the Quasi-War, an undeclared naval war. France complained the United States was ignoring the 1778 Treaty of Alliance that had brought the French into the American Revolutionary War. The United States insisted on taking a neutral stance in the war between France and Britain. After the Jay Treaty with Britain went into effect in 1795, France began to side against the United States and by 1797 had seized over 300 American merchant ships. Federalists favored Britain while Jeffersonian Republicans favored France. Federalist President John Adams built up the United States Navy, finishing three frigates, approving funds to build three more and sending diplomats to Paris to negotiate. They were insulted by Foreign Minister Talleyrand (who demanded bribes before talking). The XYZ Affair told Americans about the negotiations and angered American public opinion. The war was fought almost entirely at sea, mostly between privateers and merchant ships. In 1800, the Convention of 1800 (Treaty of Mortefontaine) ended the conflict.[61]

Second Coalition against France

Britain and Austria had been alarmed by the French creation of Sister Republics. Austria first demanded that France hand over a share of the territory of the new Republics to it. When the Directory refused, Austria began searching for partners for a new military alliance against France. The new Czar of Russia, Paul I of Russia, was extremely hostile to French republican ideas, sympathetic to the exiled Louis XVIII, and willing to join a new coalition against France. The Czar offered an army of 20,000 men, sent by sea to Holland on his Baltic fleet. He sent another army of 60,000 men, veterans of fighting in Poland and Turkey, under his best general, Alexander Suvorov, to join the Austrian forces in northern Italy.

The King of Prussia, Frederick-William III, had carefully preserved neutrality in order to profit from both sides. The Directory made the error of sending one of the most prominent revolutionaries of 1789, the Abbé Sieyés, who had voted for the death of Louis XVI, as ambassador to Berlin, where his ideas appalled the arch-conservative and ultra-monarchist king. Frederick William maintained his neutrality, refusing to support either side, a setback for France.

By the end of 1798, the coalition could count on 300,000 soldiers, and would be able to increase the number to 600,000. The best French army, headed by Bonaparte, was stranded in Egypt. General Brune had 12,000 men in Holland; Bernadotte, 10,000 men on the Rhine; Jourdan, 40,000 men in the army of the Danube; Massena, 30,000 soldiers in Switzerland; Scherer, 40,000 men on the Adige river in northern Italy; and 27,000 men under Macdonald were based in Naples: a total of 170,000 men. To try to match the coalition forces, the Directory ordered a new call up of young men between the ages of twenty and twenty five to the army, seeking to add two hundred thousand new soldiers.[62]

Resurgence of the War in Italy and Switzerland

On 10 November 1798, the British and Austrian governments had agreed on a common goal of suppressing the five new sister republics and forcing France back into its 1789 borders. Then on 29 November 1798, on the first day of the War of the Second Coalition, the King of Naples launched an attack on Rome, which was lightly defended by French soldiers. A British fleet landed three thousand Neapolitan soldiers in Tuscany. However, the French army of General Championnet responded quickly, defeating the Neapolitan army at the Battle of Civita Castellana at Civita Castellana on 5 December. The next day, 6 December 1798, French soldiers also forced the King of Sardinia to remove his soldiers from Piedmont and to retreat to his island of Sardinia, his last possession. The French army marched to the Kingdom of Naples, obliging the King of Naples to leave his City of Naples on a British warship on 23 December 1798. Naples was then occupied on 23 January 1799, and a new Neapolitan republic, the so-called Parthenopean Republic, the sixth under French protection, was proclaimed on 26 January.

Peace negotiations with Austria went nowhere in the spring of 1799, and the Directory decided to launch a new offensive into Germany, but the arrival of a Russian army under Alexander Suvorov and fresh Austrian forces under the Archduke Charles for a time changed the balance of power. Jourdan's Army of the Danube crossed the Rhine on 6 March but was defeated by the Archduke Charles, first at the Battle of Ostrach and then at the Battle of Stockach on 25 March 1799. Jourdan's army withdrew while Jourdan himself returned to Paris to plea for more soldiers.

The forces of the Second Coalition invaded French-occupied Italy, and after five earlier battles, a joint Russian-Austrian army under Suvorov's command defeated Moreau at the Battle of Cassano on 27 April 1799 and thus occupied Turin and Milan and thereby took back the Cisalpine Republic from France. Suvorov then defeated the French Army on the Terrivva. To redress the situation, Joubert was named the new head of the Army of Italy on 5 July, but his army suffered defeat by the Russians at the Battle of Novi, on 15 August; Joubert himself was shot through the heart when the battle began, and his army was routed. The Sister Republics established by the French in Italy quickly collapsed, leaving only Genoa under French control.[63]

In August, the Russians and British opened a new front in the Netherlands. A British army was landed at Helder on 27 August, and was joined by a Russian army. On 31 August, the Dutch fleet, allied with France, was defeated by the Royal Navy. Seeing the French army and government in a crisis, the leaders of the royalist rebellions in the Vendée and Brittany came together on 15 September to prepare a renewed uprising.[64]

The surviving leaders of the royalist rebellions in the Vendée and Brittany, which had long been dormant, saw a new opportunity for success and met to plan strategy on 15 September 1799. The royalist commander Louis de Frotté, in exile in England, returned to France to command the new uprising.[64]

Bonaparte's Campaign in Syria (February–May 1799)

While the French armies in Italy and Switzerland tried to preserve the Sister Republics, Bonaparte pursued his own campaign in Egypt. He explained in a letter to the Directory that Egyptian venture was just the beginning of a broader campaign "to create a formidable diversion in the campaign of Republican France versus monarchic Europe. Egypt would be the base of something much larger than the original project, and at the same time a lever which will aid in the creation of a general uprising of the Muslim world." This uprising, he believed, would lead to the collapse of British power from the Middle East to India.[63] With this goal in mind, he left Cairo and marched his army across the Sinai desert into Syria, where he laid siege to the port of Saint-Jean-d'Acre of the Ottoman Empire, which was defended by a local army and supplied by a British fleet offshore. His long siege and attempts to storm the city were a failure; his army was ravaged by disease, it was down to 11,000 men, and he learned that an Ottoman army was to be embarked by the British fleet to sail to Cairo to recapture the city. On 17 May, he abandoned the siege and was back in Cairo by 4 June. The British fleet landed the Ottoman army, but as soon as they were ashore they were decisively defeated by Bonaparte at the Battle of Aboukir on 25 July 1799.[65]

Due to the British blockade of Egypt, Bonaparte had received no news from France for six months. He sent one of his military aides to meet with Turkish government officials and to try to get news from France, but the officer was intercepted by the British navy. The British admiral and naval commander in the eastern Mediterranean, Sir Sidney Smith, who had lived in Paris and knew France well, gave the officer a packet of recent French newspapers and sent him back to Bonaparte. Bonaparte spent the night reading the newspapers, learning about the political and military troubles in France. His orders permitted him to return home any time he chose. The next day he decided to return to France immediately. He handed over command of the army to General Kléber and left Egypt with a small party of senior officers aboard the frigate La Muiron. He escaped the British blockade but did not reach France until 9 October.[66]

Tide turns: French successes (September 1799)

The military position of France, which seemed disastrous during the summer, improved greatly in September. On 19 September, General Brune won a victory over the British-Russian army in the Netherlands at Castricum. On 18 October, besieged by Brune at Alkmaar, the British-Russian forces under the Duke of York agreed to withdraw. In Switzerland, a Russian Empire Army had split into two. On 25–26 September, the French army in Switzerland, led by André Masséna, defeated one part of the Russian army under Alexander Rimsky-Korsakov at the Second Battle of Zurich, and forced the rest of the Russian army, under Suvorov, into disastrous retreat across the Alps to 'Italy'. Suvorov was furious at the Austrians, blaming them for not supporting his troops, and he urged the Czar to withdraw his forces from the war.[63]

The royalist uprising in the west of France, planned to accompany the British-Russian-Austrian offensive, was also a failure. The Chouans briefly seized Le Mans on 14 October and Nantes on 19 October, but they were quickly driven out by the French Army, and the rebellion had collapsed by 29 October.[67]

New economic crisis

Since the beginning of the Revolution, the nation suffered from rampant inflation. By the time of the Directory, the paper money, the assignat, based on the value of goods confiscated from the church and nobility, had already lost most of its value. Prices had soared, and the government could not print money fast enough to meet its expenses. The value of the assignat had dropped drastically against the value of the livre, the main unit of currency of the old regime which contained silver. In 1790, at the beginning of the Revolution, an assignat with a face value of 1,000₶. could be exchanged for 900 silver livres. In January 1795, The Convention decided to issue assignats worth 30 billion-₶., without any additional backing by gold. By March 1795, an assignat with a value of 1,000₶. could buy only 80 silver livres. In February 1796, the Directory decided to abolish the assignat, and held a public ceremony to destroy the printing plates. The assignat was replaced by a new note, the Mandat territorial. But since this new paper money also lacked any substantial backing, its value also plummeted; by February 1797 the Mandat was worth only one percent of its original value. The Directory decided to return to the use of gold or silver coins, which kept their value. 100₶. of Mandats was exchanged for 1 silver livre. The difficulty was that the Directory had only enough gold and silver to produce 300 million-₶.. The result of the shortage of money in circulation was a drastic deflation and drop in prices, which was accompanied by a drop in investment, and a drop in wages. It led to a drop in economic activity, and unemployment.[68]

New elections, new Directors and a growing political crisis

New elections to elect 315 members of the Councils were held between 21 March – 9 April 1799. The royalists had been discredited and were gone; the major winners were the neo-Jacobins, who wanted to continue and strengthen the Revolution. The new members of the Council included Lucien Bonaparte, the younger brother of Napoleon, just twenty-four years old. On the strength of his name, he was elected the President of the Council of Five Hundred.

This time the Directors did not try to disqualify the Jacobins but looked for other ways to keep control of the government. It was time to elect a new member of the Directory, as Rewbell had been designated by the drawing of lots to step down. Under the Constitution, the selection of a new member of the Directory was voted by the old members of the Councils, not the newly elected ones. The candidate selected to replace him was the Abbé Sieyés, one of the major leaders of the revolution in 1789, who had been serving as Ambassador to Berlin. Sieyés had his own project in mind: He had devised a new doctrine that the power of government should be limited in order to protect the rights of the citizens. His idea was to adopt a new Constitution with a supreme court, on the American model, to protect individual rights. He privately saw his primary mission as preventing a return of Reign of Terror of 1793, a new constitution, and bringing the Revolution to a close as soon as possible, by whatever means.[69]

Once the elections were complete, the Jacobin majority immediately demanded that the Directory be made more revolutionary. The Councils began meeting on 20 May, and on 5 June they began their offensive to turn the Directors to the left. They declared the election of the Director Treilhard illegal on technical grounds and voted to replace him with Louis-Jérôme Gohier, a lawyer who had been Minister of Justice during the Convention, and who had overseen the arrest of the moderate Girondin deputies. The Jacobins in the Council then went a step further and demanded the resignation of two moderate Directors, La Revelliere and Merlin. They were replaced by two new members, Roger Ducos, a little-known lawyer who had been a member of the Committee of Public Safety, and was an ally of Barras, and an obscure Jacobin general, Jean-François-Auguste Moulin. The new Ministers named by the Directors were for the most part reliable Jacobins, though Sieyés arranged the appointment of one of his allies, Joseph Fouché, as the new Minister of Police.[70]

The Jacobin members immediately began proposing laws that were largely favorable to the sans-culottes and working class, but which alarmed the upper and middle classes. The Councils imposed a forced loan of one hundred million francs, to be paid immediately according to a graduated scale by all who paid a property tax of over three hundred francs. Those who did not pay would be classified the same as émigré nobles and would lose all civil rights. The Councils also passed a new law that called for making hostages of the fathers, mothers and grandparents of emigre nobles whose children had emigrated or were serving in rebel bands or armies. These hostages were subject to large fines or deportation in the event of assassinations or property damage caused by royalist soldiers or bandits.[69] On 27 June General Jourdan, a prominent Jacobin member of the Councils, proposed a mass draft of all eligible young men between twenty and twenty-five to raise two hundred thousand new soldiers for the army. This would be the first draft since 1793.

The new Jacobins opened a new political club, the Club du Manège, on the model of Jacobin clubs of the Convention. It opened on 6 July and soon had three thousand members, with 250 deputies, including many alumni of the Jacobins during the Reign of Terror, as well as former supporters of the ultra-revolutionary François Babeuf. One prominent member, General Jourdan, greeted the members at the club's banquet of 14 July with the toast, "to a return of the pikes'", referring to the weapons used by the sans-culottes to parade the heads of executed nobles. The club members also were not afraid to attack the Directory itself, complaining of its lavish furnishings and the luxurious coaches used by Directory members. The Directory soon responded to the provocations; Sieyés denounced the club members as a return of Robespierre's reign of terror. The Minister of Police, Fouché, closed the Club on 13 August.[71]

Preparing the coup d'ètat

The rule that Directors must to be at least forty years old became one justification for the Coup of 18 Brumaire: the coup d'état took place on 9 November 1799, when Bonaparte was thirty years old.[72] Bonaparte returned to France, landing at the fishing village of Saint-Raphaël on 9 October 1799, and made a triumphal progression northward to Paris. His victory over the Ottoman Turks at the Battle of Aboukir had been widely reported, and overshadowed the other French victories at the Second Battle of Zurich and the Battle of Bergen. Between Avignon and Paris, he was welcomed by large, enthusiastic crowds, who saw him as a saviour of the Republic from foreign enemies and the corruption of the Directory. Upon his arrival in Paris he was elected to the Institut de France for the scientific accomplishments of his expedition to Egypt. He was welcomed by royalists because he was from a minor noble family in Corsica, and by the Jacobins because he had suppressed the attempted royalist coup d'état at the beginning of the Directory. His brother Lucien, though only twenty-four years old, became a prominent figure in the Council of Five Hundred because of his name.[73]

Bonaparte's first ambition was to be appointed to the Directory, but he was not yet forty years old, the minimum age set by the Constitution, and the Director Gohier, a strict legalist, blocked that avenue. His earliest ally had been the Director Barras, but he disliked Barras because his wife Joséphine had been his mistress before she married Bonaparte, and because of charges of corruption that surrounded Barras and his allies. Bonaparte wrote later that the Jacobin director, General Moulin, approached Bonaparte and suggested that he lead a coup d'état, but he declined; he wished to end the Revolution, not continue it.[74] Sieyés, who had been looking for a war hero and general to assist in a coup d'état, had originally in mind General Joubert, but Joubert had been killed at the Battle of Novi in August 1799. He then approached General Moreau, but Moreau was not interested. The first meeting between Sieyés and Bonaparte, on 23 October 1799, went badly; the two men each had enormous egos and instantly disliked each other. Nonetheless, they had a strong common interest and, on 6 November 1799, they formalized their plan.[73]

The coup d'état was carefully planned by Sieyès and Bonaparte, with the assistance of Bonaparte's brother Lucien, the diplomat and consummate intriguer Talleyrand, the Minister of Police Fouché, and the Commissioner of the Directory, Pierre François Réal. The plan called for three Directors to suddenly resign, leaving the country without an Executive. The Councils would then be told that a Jacobin conspiracy threatened the Nation; the Councils would be moved for their own security to the Château de Saint-Cloud, some 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) west of Paris, safe from the mobs of the French capital. Bonaparte would be named head of government to defend the Republic against the conspiracy; the Councils would be dissolved, and a new Constitution would be written. If the coup went well, it was simply a parliamentary maneuver; it would be perfectly legal. Bonaparte would provide security and take the part of convincing the Deputies. Fouché and Réal would assure that there would be no interference from the police or the city of Paris. Fouché proposed that the leading Jacobin deputies be arrested at the start of the coup, but Bonaparte said it would not be necessary, which later proved to be an error.[75] Shortly before the coup, Bonaparte met with the principal army commanders: Jourdan, Bernadotte, Augereau and Moreau, and informed them of the impending coup. They did not all support it, but agreed not to stand in his way. The president of the Council of Ancients was also brought into the coup, so he could play his part, and Bonaparte's brother Lucien would manage the Council of Five Hundred. On the evening of 6 November, the Councils held a banquet at the former church of Saint-Sulpice. Bonaparte attended, but seemed cold and distracted, and departed early.[76]

Coup d'état is launched (9–10 November)