André Masséna

André Masséna, Prince of Essling, Duke of Rivoli (born Andrea Massena; 6 May 1758 – 4 April 1817) was a French military commander during the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars.[2] He was one of the original 18 Marshals of the Empire created by Napoleon I, with the nickname l'Enfant chéri de la Victoire (the Dear Child of Victory).[3]

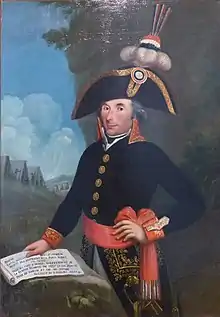

Marshal of the Empire André Masséna Duke of Rivoli, Prince of Essling | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Portrait of Masséna made c. 1853 after an 1814 original by Antoine-Jean Gros | |

| Nickname(s) | l'Enfant chéri de la Victoire |

| Born | 6 May 1758 Nice, Kingdom of Sardinia |

| Died | 4 April 1817 (aged 58) Paris, France |

| Buried | Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris, France |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | Army |

| Rank | Marshal of the Empire |

| Battles/wars | French Revolutionary Wars, Invasion of Naples (1806), Peninsular War, Napoleonic Wars |

| Awards | Grand Eagle of the Legion of Honour Grand Dignitary of Order of the Iron Crown Knight of the Order of Saint Hubert Grand Cordon of the House Order of Fidelity Commander of the Order of Saint Louis[1] |

| Signature |  |

Selected battles

| |

Many of Napoleon's generals were trained at the finest French and European military academies, however Masséna was among those who achieved greatness without the benefit of formal education. While those of noble rank acquired their education and promotions as a matter of privilege, Masséna rose from humble origins to such prominence that Napoleon referred to him as "the greatest name of my military empire".[2] His military career is equaled by few commanders in European history.

In addition to his battlefield successes, Masséna's leadership aided the careers of many. A majority of the French marshals of the time served under his command at some point.[4]

He was given the title Prince of Essling in 1809.

Early life

André Masséna was born in Nice, which was then part of the Kingdom of Sardinia, on 6 May 1758. He was the son of shopkeeper Jules Masséna (Giulio Massena), who became a wine merchant, and his wife Marguerite Fabre. André's father died in 1764, and after his mother remarried, he was sent to live with his father's relatives.

At the age of thirteen, Masséna became a cabin boy aboard a merchant ship. He sailed in the Mediterranean Sea and on two extended voyages to French Guiana. In 1775, after four years at sea, he returned to Nice and enlisted in the French Army as a private in the Royal Italian Regiment. By the time he left the service in 1789, Masséna had risen to the rank of warrant officer, the highest rank a non-noblemen could achieve. On 10 August that year, he married Anne Marie Rosalie Lamare, daughter of a surgeon in Antibes; they lived together in her home town. After a brief stint as a smuggler in Northern Italy, he rejoined the army in 1791 and was made an officer, rising to the rank of colonel by 1792.

Revolutionary Wars

When the French Revolutionary Wars broke out in April 1792, Masséna and his battalion were deployed to Piedmont along the Italian border. Masséna prepared his battalion for battle in the hope that it would be incorporated into the regular army. That October, a month after the occupation of Nice, the battalion was one of four volunteer battalions that became part of the French Armée d'Italie.

Masséna distinguished himself in battle and was quickly promoted, attaining the rank of général de brigade (brigadier general) in August 1793 and général de division (divisional general) that December. He was prominent in every campaign on the Italian Riviera over the next two years, including the attack on Saorgio in 1794 and the Battle of Loano in 1795. When Napoleon Bonaparte took command in March 1796, Masséna was commanding the two divisions of the army's advance guard.

During the campaign in Italy from 1796-1797, Masséna became one of Bonaparte's most important subordinates. He played a significant role in the battles of Montenotte and Dego in the spring, and took a leading role at the battles of Lonato, Castiglione, Bassano, Caldiero and Arcola in the summer and fall, as well as the Battle of Rivoli and the fall of Mantua that winter.

When an Austrian relief army was sent to aid Mantua in January 1797, the French forces were overrun near Rivoli, while other enemy columns advanced on Verona and Mantua. At 5:00 P.M. on 13 January, Masséna was ordered to march from Verona to Rivoli, fifteen miles away. Following a forced night march across the snow-covered roads, the first of his troops reached the battlefield at 6:00 A.M. Bonaparte deployed them on the left flank when the battle began. They were shifted to strengthen the sagging center and then deployed to crush an Austrian flanking maneuver. Masséna's troops played a decisive role in the victory. The next day, with very little rest, Masséna and his troops marched 39 miles in 24 hours to intercept a second Austrian army advancing to relieve Mantua. At La Favorita, he closed the pincer on the Austrian army, forcing their surrender. In the space of five days, Masséna's division played a major role in an operation that left over 35,000 Austrian soldiers either dead or captured. Two weeks later, the 30,000-man garrison at Mantua surrendered. With his final victory complete, Napoleon praised Masséna with the name l'enfant chéri de la victoire. The president of the Directory in Paris, Jean Rewbell, was also congratulatory: "The Executive Directory congratulates you, citizen general, for the new success that you have obtained against the enemies of the Republic. The brave division that you command has covered itself with glory in the three consecutive days that forced Mantua to capitulate, and the Directory is obliged to regard you among the most capable and useful generals of the Republic."[5]

In 1799, Masséna was granted an important command in Switzerland, replacing General Charles Edward Jennings. As Russian reinforcements marched to support the Austrian armies in Italy and Switzerland, the Directory consolidated the remnants of the French armies under Masséna's command. With a force totaling approximately 90,000 men, Masséna was ordered to defend the entire frontier. He repulsed Archduke Charles's advance on Zurich in June, but retired from the city and took up positions in the surrounding mountains.[6] He triumphed over the Russians under General Alexander Korsakov at the Second Battle of Zurich in September, then, aware of the advance of Russian general Alexander Suvorov toward St. Gotthard, quickly shifted his troops southward. General Claude Jacques Lecourbe's division delayed the Russians' entrance into Switzerland at Gotthard Pass, and when Suvorov finally forced his way through, he was met by units of General Jean-de-Dieu Soult's French division blocking the route at Altdorf. Unable to break through the French lines and aware of Korsakov's disastrous defeat, the Russian general turned east through the high and difficult Pragel Pass to Glarus where he was dismayed to find other French troops awaiting him on 4 October. In waist-deep snow, his troops attempted six times to break through the French lines along the Linth river, but each attack was beaten back. Suvorov had no alternative but to make his escape across the treacherous Panix Pass, abandoning his baggage and artillery and losing as many as 5,000 men.[7] This, among other events, led to Russia's withdrawal from the Second Coalition.

In 1800, Masséna was besieged at Genoa in Italy by the Austrians, while Bonaparte marched with the Army of the Reserve to Milan. By the end of May, plague had spread throughout Genoa and the civilian population was in revolt. Negotiations were begun for the exchange of prisoners early in June, but the citizens and some of the garrison clamored for capitulation. Unknown to Masséna, the Austrian general Peter Ott had been ordered to raise the siege because Bonaparte had crossed Great St Bernard Pass and was now threatening the main Austrian army. Describing the situation at Genoa, Ott requested and received permission to continue the siege. On 4 June, with one day's rations remaining, Masséna's negotiator finally agreed to evacuate the French Army from Genoa. However, "if the word capitulation was mentioned or written", Masséna threatened to end all negotiations.[8] Two days later, a few of the French left the city by sea, but the bulk of Masséna's starving and exhausted troops marched out of the city with all their equipment and followed the road along the coast toward France, ending the siege of almost 60 days. The siege was an astonishing demonstration of tenacity, ingenuity, courage, and daring that garnered additional laurels for Masséna and placed him in a category previously reserved for Bonaparte alone.[4]

By forcing the Austrians to deploy vast forces against him at Genoa, Masséna made it possible for Bonaparte to cross Great St Bernard Pass, surprise the Austrians, and ultimately defeat General Michael von Melas's Austrian army at Marengo before sufficient reinforcements could be transferred from the siege site. Less than three weeks after the evacuation, Bonaparte wrote to Masséna, "I am not able to give you a greater mark of the confidence I have in you than by giving you command of the first army of the Republic [Army of Italy]."[9] Even the Austrians recognized the significance of Masséna's defense; the Austrian chief of staff declared firmly, "You won the battle, not in front of Alessandria but in front of Genoa."[10] Masséna was made commander of French forces in Italy, though he was later dismissed by Napoleon. Despite the praise, Napoleon also criticized Massena for capitulating too early in his memoirs, contrasting his actions with those of the Gauls under Vercingetorix when besieged by Julius Caesar in the Battle of Alesia.[11]

Napoleonic Wars

.jpg.webp)

Not until 1804 did Masséna regain Napoleon's trust. That year, he was made a Marshal of the Empire in May. He led an independent army that captured Verona and fought the Austrians at Verona and later, on 30 October 1805, Caldiero. Masséna was given control of operations against the Kingdom of Naples, and commanded the right wing of the Grand Army in Poland in 1807. He was granted his first ducal victory title as chief of Rivoli on 24 August 1808.

In 1804, he participated in the reorganization of French Freemasonry and became, in November, "grand representative of the grand master of the Supreme Council"; in this capacity, he is one of the negotiators of the concordat established between the Grand Orient de France and the Supreme Council. Under the Empire, he was a member of the Sainte Caroline lodge in Paris.[12] He is also "worshipful of honor" in various Masonic lodges, such as "Les Frères Réunis" in Paris, "La Parfaite Amitié" in Toulon, "L'Étroite Union" in Thouars or "Les Vrais Amis Réunis" in Nice.

In 1808, Masséna was accidentally shot during a hunting expedition with the imperial suite. It is unclear as to whether he was shot by Napoleon himself or by Marshal Louis-Alexandre Berthier, but he lost the use of one eye as a result.

It was not until 1809 that he returned to active service, this time against the forces of the Fifth Coalition. At the beginning of the campaign, Masséna led the IV Corps at the battles of Eckmühl and Ebersberg. Later in the war, when Napoleon tried to cross to the north bank of the Danube at the Battle of Aspern-Essling, Masséna's troops hung onto the village of Aspern through two days of savage fighting. He was rewarded on 31 January 1810 with a second, now princely, victory title, Prince of Essling, for his efforts there and in the Battle of Wagram.

During the Peninsular War, Napoleon appointed Masséna as Commander of the Army of Portugal in 1810. Masséna captured Ciudad Rodrigo and Almeida after successful sieges, but suffered a setback at the hands of the Duke of Wellington's Anglo-Portuguese army at Buçaco on 27 September. Pressing on, he forced the allies to retreat into the Lines of Torres Vedras, where a stalemate ensued for several months. Finally forced to retreat due to lack of food and supplies, Masséna withdrew to the Spanish frontier, allegedly prompting Napoleon to comment, "So, Prince of Essling, you are no longer Masséna."[13] After suffering defeats at the battles of Sabugal and Fuentes de Oñoro, he was replaced by Marshal Auguste de Marmont and did not serve again, becoming a local commander at Marseille.

Retirement

Masséna retained briefly his command after the restoration of King Louis XVIII until he was removed for his background.[14] When Napoleon returned from exile the following year, Masséna took Napoleon's side once again, and was awarded as a Peer of France but remained as a local commander. The day after Napoleon's second abdication on 22 June 1815, he was named head of the National Guard in Paris by the Provisional Government, but was soon replaced upon the return of the Bourbons.[15] He was disinclined to prove his royalist loyalties after the defeat of Napoleon, and was also a member of the court-martial that refused to try Marshal Michel Ney. Masséna died in Paris in 1817 and was buried at Père Lachaise Cemetery, in a tomb he shares with his son-in-law Honoré Charles Reille.[16]

Family

Masséna's wife stayed at their home in Antibes during his campaigns. Their first child, Marie Anne Elisabeth, was born on 8 July 1790, but died only four years later. Their first son Jacques Prosper, born 25 June 1793, inherited his father's title as 2nd Prince of Essling on 3 July 1818. Victoire Thècle was born on 28 September 1794 and married Honoré Charles Reille on 12 September 1814. François Victor, born on 2 April 1799, became 2nd Duke of Rivoli, 3rd Prince of Essling, and married Anne Debelle on 19 April 1823.

Legacy

Masséna is the namesake of one of the Boulevards of the Marshals that circle Paris, having also a bridge named after him.

The village of Massena in New York was settled by French lumbermen in the early 19th century and named in Masséna's honor. Massena, Iowa, also in the United States and in turn named for the community in New York, honors Masséna with a portrait of him in Centennial Park. His birthplace, Nice, is the location of Place Masséna, also named after him.

In literature

- Masséna is mentioned and/or appears in several of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's Brigadier Gerard stories, including How the Brigadier Saved the Army (1902).

- Masséna appears as a minor character in Bernard Cornwell's novels Sharpe's Escape, detailing France's failed attempt to re-invade Portugal in 1810, including the Battle of Bussaco, and Sharpe's Battle, detailing the Battle of Fuentes de Oñoro.

References

- Paris, Louis (1869). Dictionnaire des anoblissements (in French). Vol. 1. Paris: Bachelin-Deflorenne.

- Donald D. Horward, ed., trans, annotated, The French Campaign in Portugal, An Account by Jean Jacques Pelet, 1810-1811 (Minneapolis, MN, 1973), 501.

- General Michel Franceschi (Ret.), Austerlitz (Montreal: International Napoleonic Society, 2005), 20.

- "INS Scholarship 1997: André Masséna, Prince D'Essling, in the Age of Revolution". Napoleon-series.org. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- Rewbell to Masséna, 14 February 1797, Koch, Mémories de Masséna I, lxxxix.

- Marshall-Cornwall, Massena, 72-74.

- Édouard Gachot, Histoire militaire de Masséna, La Campagne d'Helvétie (1799) (Paris, 1904), 182-473.

- Masséna to Ott, 2 June 1800, Gachot, Le Siège de Gênes, 241.

- Bonaparte to Masséna, 25 June 1800, Correspondance de Napoléon Ier, No. 4951, VI, 489-90.

- James Marshall-Cornwall, Marshal Massena, 115.

- Roberts, Andrew (2014). Napoleon: A Life. Penguin. p. 330.

- Dictionnaire de la franc-maçonnerie - Daniel Ligou (Presses universitaires de France, 1998).

- Napoleon's Peninsular Marshals: A Reassessment. Richard Humble, 1972.

- Elting, Swords Around a Throne, 141.

- Thibaudeau, Memoires, 1799 - 1815, 519.

- Monuments and Memorials of the Napoleonic Era. Honoré Charles Reille

- Chandler, David, ed. (1987). Napoleon's Marshals. London: Macmillan Publishing Company. ISBN 0-297-79124-9.

- Chandler, David (1966). The Campaigns of Napoleon. New York: Macmillan.

- Clausewitz, Carl von (2018). Napoleon's 1796 Italian Campaign. Trans and ed. Nicholas Murray and Christopher Pringle. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-2676-2

- Clausewitz, Carl von (2020). Napoleon Absent, Coalition Ascendant: The 1799 Campaign in Italy and Switzerland, Volume 1. Trans and ed. Nicholas Murray and Christopher Pringle. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-3025-7

- Clausewitz, Carl von (2021). The Coalition Crumbles, Napoleon Returns: The 1799 Campaign in Italy and Switzerland, Volume 2. Trans and ed. Nicholas Murray and Christopher Pringle. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-3034-9

- Smith, Digby (1998). The Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill. ISBN 1-85367-276-9.

External links

- Heraldry.prg - Napoleonic heraldry

- André Masséna, Prince D'Essling, in the Age of Revolution (1789-1815) by Donald D. Horward for the "Journal of the International Napoleonic Society"

- Beach, Chandler B., ed. (1914). . . Chicago: F. E. Compton and Co.

.svg.png.webp)