Sabre

A sabre (French: [ˈsabʁ], or saber in American English) is a type of backsword with a curved blade associated with the light cavalry of the early modern and Napoleonic periods. Originally associated with Central European cavalry such as the hussars, the sabre became widespread in Western Europe during the Thirty Years' War. Lighter sabres also became popular with infantry of the early 17th century. In the 19th century, models with less curving blades became common and were also used by heavy cavalry.

| Sabre | |

|---|---|

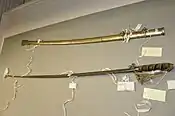

Sheathed French sabres of the sailors of the Guard, First French Empire | |

| Type | Sword |

| Service history | |

| Wars | Early Modern warfare, Ottoman Wars, Napoleonic Wars, American Revolution, American Civil War, Franco-Prussian War, Philippine Revolution, Spanish–American War, Philippine–American War, World War I, Polish–Soviet War, World War II |

| Production history | |

| Produced | Early modern period |

The military sabre was used as a duelling weapon in academic fencing in the 19th century, giving rise to a discipline of modern sabre fencing (introduced in the 1896 Summer Olympics) loosely based on the characteristics of the historical weapon in that it allows for cuts as well as thrusts.

Etymology

The English sabre is recorded from the 1670s, as a direct loan from French, where the sabre is an alteration of sable, which was in turn loaned from German Säbel, Sabel in the 1630s. The German word is on record from the 15th century, loaned from Polish szabla, which was itself adopted from Hungarian szabla (14th century, later szablya). The spread of the Hungarian word to neighboring European languages took place in the context of the Ottoman wars in Europe of the 15th to 17th centuries. The spelling saber became common in American English in the second half of the 19th century.[1]

The origin of the Hungarian word is unclear. It may itself be a loan from South Slavic (Serbo-Croatian сабља, Common Slavic *sablja), which would ultimately derives from a Turkic source.[2] In a more recent suggestion, the Hungarian word may ultimately derive from a Tungusic source, via Kipchak Turkic selebe, with later metathesis (of l-b to b-l) and apocope changed to *seble, which would have changed its vocalisation in Hungarian to the recorded sabla (perhaps under the influence of the Hungarian word szab- "to crop; cut (into shape)".[3]

History

Origins

Though single-edged cutting swords already existed in the Ancient world, such as the ancient Egyptian and Sumerian sickle swords, these (usually forward instead of backward curving) weapons were chopping weapons for foot soldiers. This type of weapon developed into such heavy chopping weapons as the Greek Machaira and Anatolian Drepanon, and it still survives as the heavy Kukri chopping knife of the Gurkhas. However, in ancient China foot soldiers and cavalry often used a straight, single edged sword, and in the sixth century CE a longer, slightly curved cavalry variety of this weapon appeared in southern Siberia. This "proto-sabre" (the Turko-Mongol sabre) had developed into the true cavalry sabre by the eight century CE, and by the ninth century, it had become the usual side arm on the Eurasian steppes. The sabre arrived in Europe with the Magyars and the Turkic expansion.[4][5][6] These oldest sabres had a slight curve, short, down-turned quillons, the grip facing the opposite direction to the blade and a sharp point with the top third of the reverse edge sharpened.[7][8]

Early modern period

_The_Sword_Dance%252C_Private_Collection.jpg.webp)

The introduction of the sabre proper in Western Europe, along with the term sabre itself, dates to the 17th century, via the influence of the szabla type ultimately derived from these medieval backswords. The adoption of the term is connected to the employment of Hungarian hussar (huszár) cavalry by Western European armies at the time. Hungarian hussars were employed as light cavalry, with the role of harassing enemy skirmishers, overrunning artillery positions, and pursuing fleeing troops. In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, many Hungarian hussars fled to other Central and Western European countries and became the core of light cavalry formations created there.[9] The Hungarian term szablya is ultimately traced to the northwestern Turkic selebe, with contamination from the Hungarian verb szab "to cut".[10]

The original type of sabre, or Polish szabla, was used as a cavalry weapon, possibly inspired by Hungarian or wider Turco-Mongol warfare.

The karabela was a type of szabla popular in the late 17th century, worn by the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth nobility class, the szlachta. While designed as a cavalry weapon, it also came to replace various types of straight-bladed swords used by infantry.[11] The Swiss sabre originated as a regular sword with a single-edged blade in the early 16th century, but by the 17th century began to exhibit specialized hilt types.

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

In the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (16th–18th century) a specific type of sabre-like melee weapon, the szabla, was used. Richly decorated sabres were popular among the Polish nobility, who considered it to be one of the most important pieces of men's traditional attire. With time, the design of the sabre greatly evolved in the commonwealth and gave birth to a variety of sabre-like weapons, intended for many tasks. In the following centuries, the ideology of Sarmatism as well as the Polish fascination with Oriental cultures, customs, cuisine and warfare resulted in the szabla becoming an indispensable part of traditional Polish culture.

Modern use

Stewart%252C_Later_3rd_Marquess_of_Londonderry%252C_1812%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_National_Portrait_Gallery%252C_London.jpg.webp)

The sabre saw extensive military use in the early 19th century, particularly in the Napoleonic Wars, during which Napoleon used heavy cavalry charges to great effect against his enemies. Shorter versions of the sabre were also used as sidearms by dismounted units, although these were gradually replaced by fascine knives and sword bayonets as the century went on. Although there was extensive debate over the effectiveness of weapons such as the sabre and lance, the sabre remained the standard weapon of cavalry for mounted action in most armies until World War I and in a few armies until World War II. Thereafter it was gradually relegated to the status of a ceremonial weapon, and most horse cavalry was replaced by armoured cavalry from the 1930s onward.

Where horse mounted cavalry survived into World War II it was generally as mounted infantry without sabres. However the sabre was still carried by German cavalry until after the Polish campaign of 1939, after which this historic weapon was put into storage in 1941.[12] Romanian cavalry continued to carry their straight "thrusting" sabres on active service until at least 1941.[13][14]

Napoleonic era

Sabres were commonly used by the British in the Napoleonic era for light cavalry and infantry officers, as well as others. The elegant but effective 1803 pattern sword that the British Government authorized for use by infantry officers during the wars against Napoleon featured a curved sabre blade which was often blued and engraved by the owner in accordance with his personal taste, and was based on the famously agile 1796 light cavalry sabre that was renowned for its brutal cutting power. Sabres were commonly used throughout this era by all armies, in much the same way that the British did.

The popularity of the sabre had rapidly increased in Britain throughout the 18th century for both infantry and cavalry use. This influence was predominately from southern and eastern Europe, with the Hungarians and Austrians listed as sources of influence for the sword and style of swordsmanship in British sources. The popularity of sabres had spread rapidly through Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries, and finally came to dominance as a military weapon in the British army in the 18th century, though straight blades remained in use by some, such as heavy cavalry units. (These were also replaced by sabres soon after the Napoleonic era).

The introduction of 'pattern' swords in the British army in 1788 led to a brief departure from the sabre in infantry use (though not for light cavalry), in favour of the lighter and straight bladed spadroon. The spadroon was universally unpopular, and many officers began to unofficially purchase and carry sabres once more. In 1799, the army accepted this under regulation for some units, and in 1803, produced a dedicated pattern of sabre for certain infantry officers (flank, rifle and staff officers). The 1803 pattern quickly saw much more widespread use than the regulation intended due to its effectiveness in combat, and fashionable appeal.

Pattern 1796 light cavalry sabre

The most famous British sabre of the Napoleonic era is the 1796 light cavalry model, used by troopers and officers alike (officers versions can vary a little, but are much the same as the pattern troopers sword). It was in part designed by the famous John Le Marchant, who worked to improve on the previous (1788) design based on his experience with the Austrians and Hungarians. Le Marchant also developed the first official British military sword exercise manual based on this experience, and his light cavalry sabre, and style of swordsmanship went on to heavily influence the training of the infantry and the navy.

The 1796 light cavalry sword was known for its brutal cutting power, easily severing limbs, and leading to the (unsubstantiated) myth that the French put in an official complaint to the British about its ferocity. This sword also saw widespread use with mounted artillery units, and the numerous militia units established in Britain to protect against a potential invasion by Napoleon.

Mameluke swords

Though the sabre had already become very popular in Britain, experience in Egypt did lead to a fashion trend for mameluke sword style blades, a type of Middle Eastern scimitar, by some infantry and cavalry officers. These blades differ from the more typical British ones in that they have more extreme curvatures, in that they are usually not fullered, and in that they taper to a finer point. Mameluke swords also gained some popularity in France as well. Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, himself carried a mameluke-style sword. In 1831, the 'Mameluke' sword became the pattern sword for British generals, as well as officers of the United States Marine Corps; in this last capacity, it is still in such use at the present time.

United States

The American victory over the rebellious forces in the citadel of Tripoli in 1805, during the First Barbary War, led to the presentation of bejewelled examples of these swords to the senior officers of the US Marines. Officers of the US Marine Corps still use a mameluke-pattern dress sword. Although some genuine Turkish kilij sabres were used by Westerners, most "mameluke sabres" were manufactured in Europe; although their hilts were very similar in form to the Ottoman prototype, their blades, even when an expanded yelman was incorporated, tended to be longer, narrower and less curved than those of the true kilij.

In the American Civil War, the sabre was used infrequently as a weapon, but saw notable deployment in the Battle of Brandy Station and at East Cavalry Field at the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863. Many cavalrymen—particularly on the Confederate side—eventually abandoned the long, heavy weapons in favour of revolvers and carbines.

The last sabre issued to US cavalry was the Patton saber of 1913, designed to be mounted to the cavalryman's saddle. The Patton saber is only a saber on name. It is a straight, thrust-centric sword. A US War Department circular dated 18 April 1934 announced that the saber would no longer be issued to cavalry, and that it was to be completely discarded for use as a weapon. Only dress sabers, for use by officers only, and strictly as a badge of rank, were to be retained.[15]

Police

During the 19th and into the early 20th century, sabres were also used by both mounted and dismounted personnel in some European police forces. When the sabre was used by mounted police against crowds, the results could be devastating, as portrayed in a key scene in Doctor Zhivago. The sabre was later phased out in favour of the baton, or nightstick, for both practical and humanitarian reasons. The Gendarmerie of Belgium used them until at least 1950,[16] and the Swedish police forces until 1965.[17]

Contemporary dress uniform

Swords with sabre blades remain a component of the dress uniforms worn by most national army, navy, air force, marine and coast guard officers. Some militaries also issue ceremonial swords to their highest-ranking non-commissioned officers; this is seen as an honour since, typically, non-commissioned, enlisted/other-rank military service members are instead issued a cutlass blade rather than a sabre. Swords in the modern military are no longer used as weapons, and serve only ornamental or ceremonial functions. One distinctive modern use of sabres is in the sabre arch, performed for servicemen or women getting married.

Modern sport fencing

The modern fencing sabre bears little resemblance to the cavalry sabre, having a thin, 88 cm (35 in) long straight blade. Rather, it is based upon the Italian dueling saber of classical fencing. One of the three weapons used in the sport of fencing, it is a very fast-paced weapon with bouts characterized by quick footwork and cutting with the edge. The valid target area is from the waist up excluding the hands.

The concept of attacking above the waist only is a 20th-century change to the sport; previously sabreurs used to pad their legs against cutting slashes from their opponents. The reason for the above waist rule is unknown,[18] as the sport of sabre fencing is based on the use of infantry sabres, not cavalry sabres.

In the last years, Saber fencing has been developing in Historical European Martial Arts, with blades that closely resemble the historical types, with techniques based on historical records.

See also

- Pattern 1796 light cavalry sabre

- Pattern 1908 and 1912 cavalry swords

- Szabla wz. 34

- Sabrage, the act of opening a Champagne bottle with a sabre

- Buffalo Sabres, the American professional ice hockey team that takes their name from the sword

- Cutlass, the Western European equivalent

- Dao, the Chinese equivalent

- Scimitar, the Arab equivalent

- Shamshir, the Persian equivalent

- Szabla, the Central and Eastern European equivalent

- Talwar, the South Asian equivalent

- Turko-Mongol sabers, the East Asian equivalent

- Zulfiqar, the sword of ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib

- Barbourofelidae, and Nimravidae, feliforms of which some members are called "sabre-toothed cats"

- Machairodontinae, the group of felids commonly called "sabre-toothed cats"

- Lightsaber, a fictional sword-like melee weapon used in the Star Wars universe

References

- e.g. Report on the Military Academy at West Point, United States Congressional serial set, Volume 1089, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1861, p. 218.

- There are some alternative suggestions, deriving the term from a natively Slavic word; e.g. Brückner (Słownik etymologiczny języka polskiego. 1927) adduced Slavi sabl "rooster" and Menges (The Oriental elements in the vocabulary of the oldest Russian epos, 1951) attempted to connect the Arabic saif.

- Possible Tungusic cognates include Manchu seleme "dagger", Evenk sälämä "sword", argued to be a natively Tungusic formation of sele "iron" plus a denominal suffix -me by Stachowski (2004). Marek Stachowski, "The Origin of the European Word for Sabre", Studia Etymologica Cracoviensia 9 (2004), p. 135, citing V. Rybatzki, Studia Etymologica Cracoviensia 7 (2002), p. 115), Menges, Ural-altaische Jahrbücher. Neue Folge 3 (1983), p. 125.

- Gamber, O. (1978) Waffe und Rüstung Eurasiens , p. 84, 98, 120, 124, 280

- Nicolle, D. (2007) Attila and the Nomad Hordes, p. 48

- Nicolle, D. (1990) Crusader Warfare: Muslims, Mongols and the struggle against the Crusades, p. 175. Fashion, Forensic. "Magyar". Forensic Fashion. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- Imperial, Manning. "Catalogue". Manning Imperial. Manning Imperial. Archived from the original on 24 July 2015. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- Lángó, Péter. "Archaeological Research on the Conquering Hungarians. A Review". Academia.edu. Academia.edu. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- Bavaria raised its first hussar regiment in 1688 and a second one in about 1700. Prussia followed suit in 1721 when Frederick the Great used hussar units extensively during the War of the Austrian Succession. France established a number of hussar regiments from 1692 onward, recruiting originally from Hungary and Germany, then subsequently from German-speaking frontier regions within France itself. The first hussar regiment in France was founded by a Hungarian lieutenant named Ladislas Ignace de Bercheny. Hungarian-history.hu Archived 15 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Marek Stachowski (2004). "The origin of the European word for sabre" (PDF). Studia Etymologica Cracoviensia. Krakow. 9.

- Alaux, Michel. Modern Fencing: Foil, Epee, and Sabre. Scribner's, 1975, p. 123.

- Fowler, Jeffrey T. (25 November 2001). Axis Cavalry in World War II. p. 43. ISBN 1-84176-323-3.

- Fowler, Jeffrey T. (25 November 2001). Axis Cavalry in World War II. p. 46. ISBN 1-84176-323-3.

- Klaus Richter, Weapons & Equipment of the German Cavalry: 1935-1945, p. 25, ISBN 978-0-8874-0816-8

- Randy Staffen, pages=76–77 "The Horse Soldier 1776–1943, Volume IV", UE443.S83, University of Oklahoma 1979

- BELGIUM SAYS 'NO' TO LEOPOLD (Newsreel). Pathé News. 3 August 1950.

- RAMSEY., SYED (12 May 2016). Tools of war;history of weapons in medieval times. [Place of publication not identified]: ALPHA EDITIONS. ISBN 9789386019813. OCLC 971222281.

- J. Christoph Amberger, The Secret History of the Sword, 1996 Hammerterz Forum, revised edition 1999 Multi-media Books, Inc. ISBN 1-892515-04-0

- W. Kwaśniewicz, Dzieje szabli w Polsce, Warszawa (History of the Sabre in Poland), Dom wydawniczy Bellona, 1999 ISBN 83-11-08894-2.

- Wojciech Zablocki, "Ciecia Prawdziwa Szabla", Wydawnictwo "Sport i Turystyka" (1989) (English abstract by Richard Orli, 2000, kismeta.com).

- Richard Marsden, The Polish Saber, Tyrant Industries (2015)