French protectorate in Morocco

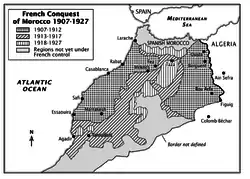

The French protectorate in Morocco (French: Protectorat français au Maroc; Arabic: الحماية الفرنسية في المغرب), also known as French Morocco, was the French military occupation of a large part of Morocco established in the form of a colonial regime imposed by France while preserving the Moroccan royal regime known as the Sherifian Empire under French rule.[5] The protectorate was officially established 30 March 1912, when Sultan Abd al-Hafid signed the Treaty of Fes, though the French military occupation of Morocco had begun with the invasion of Oujda and the bombardment of Casablanca in 1907.[5]

French protectorate in Morocco | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1912–1956 | |||||||||

.svg.png.webp) Coat of arms

| |||||||||

| Anthem: | |||||||||

The French conquest of Morocco, c. 1907–1927[3] | |||||||||

| Status | Protectorate of France | ||||||||

| Capital | Rabat | ||||||||

| Common languages | Arabic French Berber | ||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy under colonial administration | ||||||||

| Sultan | |||||||||

• 1912–1927 | Yusef | ||||||||

• 1927–1953 | Mohammed V | ||||||||

• 1953–1955 | Mohammed VI[lower-alpha 1] | ||||||||

• 1955–1956 | Mohammed V | ||||||||

| Resident-General | |||||||||

• 1912–1925 (first) | Hubert Lyautey | ||||||||

• 1955–1956 (last) | André Louis Dubois | ||||||||

| Historical era | Interwar period | ||||||||

• Treaty of Fes | 30 March 1912 | ||||||||

| 7 April[4] 1956 | |||||||||

| Currency | Moroccan rial (1912–1921) Moroccan franc (1921–1956) French franc (de facto in some areas) | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The French protectorate lasted until the dissolution of the Treaty of Fes on 2 March 1956, with the Franco-Moroccan Joint Declaration.[6] Morocco's independence movement, described in Moroccan historiography as the Revolution of the King and the People, restored the exiled Muhammad V but it did not end French presence in Morocco. France preserved its influence in the country, including a right to station French troops and to have a say in Morocco's foreign policy. French settlers also maintained their rights and property.[7]

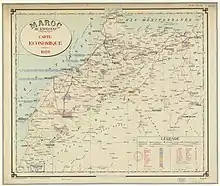

The French protectorate shared territory with the Spanish protectorate, established and dissolved in the same years; its borders consisted of the area of Morocco between the "Corridor of Taza" and the Draa River, including sparse tribal lands, and the official capital was Rabat.

Prelude

.jpg.webp)

Despite the weakness of its authority, the 'Alawi dynasty distinguished itself in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries by maintaining Morocco’s independence while other states in the region succumbed to French or British domination. However, in the latter part of the nineteenth century, Morocco’s weakness and instability invited European intervention to protect threatened investments and to demand economic concessions. This culminated in the signing of the Treaty of Madrid in 1880. The first years of the twentieth century witnessed a rush of diplomatic maneuvering through which the European powers and France, in particular, furthered their interests in North Africa.[8]

French activity in Morocco began at the end of the nineteenth century. In 1904 the French government was trying to establish a protectorate over Morocco and had managed to sign two bilateral secret agreements with Britain (8 April 1904, see Entente cordiale) and Spain (7 October 1904), which guaranteed the support of the powers in question in this endeavor. That same year, France sponsored the creation of the Moroccan Debt Administration in Tangier. France and Spain secretly partitioned the territory of the sultanate, with Spain receiving concessions in the far north and south of the country.[9]

First Moroccan Crisis: March 1905 – May 1906

The First Moroccan Crisis grew out of the imperial rivalries of the great powers, in this case, between Germany on one side and France, with British support, on the other. Germany took immediate diplomatic action to block the new accord from going into effect, including the dramatic visit of Wilhelm II to Tangier in Morocco on 31 March 1905. Kaiser Wilhelm tried to get Morocco's support if they went to war with France or Britain, and gave a speech expressing support for Moroccan independence, which amounted to a provocative challenge to French influence in Morocco.[10]

In 1906 the Algeciras Conference was held to settle the dispute, and Germany accepted an agreement in which France agreed to yield control of the Moroccan police, but otherwise retained effective control of Moroccan political and financial affairs. Although the Algeciras Conference temporarily solved the First Moroccan Crisis it only worsened international tensions between the Triple Alliance and the Triple Entente.[11]

French invasion

.jpg.webp)

The French military conquest of Morocco began in the aftermath of Émile Mauchamp's assassination in Marrakesh on 19 March 1907. In the French press, his death was characterized as an "unprovoked and indefensible attack from the barbarous natives of Morocco."[12] Hubert Lyautey seized his death as a pretext to invade Oujda from the east.[12]

In the summer of 1907, tribes of the Chaouia led a revolt against the application of terms in the 1906 Treaty of Algeciras in Casablanca, killing 9 European laborers working on the rail line between the port and a quarry in Roches Noires.[13] The French responded with a naval bombardment of Casablanca from 5–7 August, and went on to occupy and "pacify" Casablanca and the Chaouia plain, marking the beginning of the French invasion from the west.[14][15]

Hafidiya

Abdelaziz did virtually nothing in response to French aggressions and occupation of Oujda and the Chaouia. As a result, there was growing pressure jihad in defense of Morocco, particularly from Muhammad al-Kattani and the people of Fes. After the southern aristocrats pledged support to the sultan's brother, Abd al-Hafid, the people of Fes also pledged their support, though qualified by an unprecedented Conditional Bay'ah.[16] France supported Abdelaziz and promoted him in their propaganda newspaper Es-Saada (السعادة).[17]

Agadir Crisis

In 1911, a rebellion broke out in Morocco against the Sultan, Abdelhafid. By early April 1911, the Sultan was besieged in his palace in Fez and the French prepared to send troops to help put down the rebellion under the pretext of protecting European lives and property. The French dispatched a flying column at the end of April 1911 and Germany gave approval for the occupation of the city. Moroccan forces besieged the French-occupied city. Approximately one month later, French forces brought the siege to an end. On 5 June 1911 the Spanish occupied Larache and Ksar-el-Kebir. On 1 July 1911 the German gunboat Panther arrived at the port of Agadir. There was an immediate reaction from the French, supported by the British.[18]

French protectorate (1912–1956)

| History of Morocco |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

|

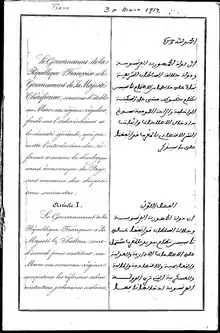

France officially established a protectorate over Morocco with the Treaty of Fes,[19] ending what remained of the country's de facto independence. From a strictly legal point of view, the treaty did not deprive Morocco of its status as a sovereign state. The Sultan reigned but did not rule. Sultan Abdelhafid abdicated in favour of his brother Yusef after signing the treaty. On 17 April 1912, Moroccan infantrymen mutinied in the French garrison in Fez, in the 1912 Fes riots[20] The Moroccans were unable to take the city and were defeated by a French relief force. In late May 1912, Moroccan forces again unsuccessfully attacked the enhanced French garrison at Fez.

In establishing their protectorate over much of Morocco, the French had behind them the experience of the conquest of Algeria and of their protectorate over Tunisia; they took the latter as the model for their Moroccan policy. There were, however, important differences. First, the protectorate was established only two years before the outbreak of World War I, which brought with it a new attitude toward colonial rule. Rejecting the typical French assimilationist approach to culture and education as a liberal fantasy, Morocco's conservative French rulers attempted to use urban planning and colonial education to prevent cultural mixing and to uphold the traditional society upon which the French depended for collaboration.[21] Second, Morocco had a thousand-year tradition of independence and had never been subjected to Ottoman rule, though it had been strongly influenced by the civilization of Muslim Iberia.

Morocco was also unique among the North African countries in possessing a coast on the Atlantic, in the rights that various nations derived from the Conference of Algeciras, and in the privileges that their diplomatic missions had acquired in Tangier (including a French legation). Thus the northern tenth of the country, with both Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts, were excluded from the French-controlled area and treated as a Spanish protectorate.

Although being under protectorate, Morocco retained -de jure- its personality as a state in international law, according to an International Court of Justice statement, and thus remained a sovereign state, without discontinuity between pre-colonial and modern entities.[22] In fact, the French enjoyed much larger powers.

Under the protectorate, French civil servants allied themselves with the French colonists and with their supporters in France to prevent any moves in the direction of Moroccan autonomy. As pacification proceeded, the French government promoted economic development, particularly the exploitation of Morocco’s mineral wealth, the creation of a modern transportation system, and the development of a modern agriculture sector geared to the French market. Tens of thousands of colonists entered Morocco and bought up large amounts of the rich agricultural land. Interest groups that formed among these elements continually pressured France to increase its control over Morocco.

World War I

France recruited infantry from Morocco to join its troupes coloniales, as it did in its other colonies in Africa and around the world. Throughout World War I, a total of 37,300–45,000 Moroccans fought for France, forming a "Moroccan Brigade."[24][23] Moroccan colonial troops first served France in the First Battle of the Marne, September 1914,[23] and participated in every major battle in the war,[25] including in Artois, Champagne, and Verdun.[24] Historians have called these Moroccan soldiers "heroes without glory" as they are not and have not been given the consideration they merited through valor and sacrifice in the war.[24] Brahim El Kadiri Boutchich identified the participation of Moroccan soldiers in the service of France in WWI as "one of the most important moments in the shared history of Morocco and France."[24]

Lyautey and the Protectorate (1912–1925)

Hubert Lyautey, the first Resident-General of the Protectorate, was an idealistic yet pragmatic leader with royalist leanings, who made it his mission to develop Morocco in every sector under French influence. Unlike his compatriots, Lyautey didn't believe that France should directly annex Morocco like French Algeria, but rather remodel and re-educate Moroccan society. He promised that, in this process, he would:

...offend no tradition, change no custom, and remind ourselves that in all human society there is a ruling class, born to rule, without which nothing can be done...[we] enlist the ruling class in our service...and the country will be pacified, and at far less cost and with greater certainty than by all the military expeditions we could send there...

Lyautey's vision was ideological: A powerful, pro-French, Westernized monarchy that would work with France and look to France for culture and aid. Unlike in Algeria, where the entire nobility and government had been displaced, the Moroccan nobility was included in Lyautey's plans. He worked with them, offering support and building elite private schools to which they could send their children; one notable product of this schooling was Thami El Glaoui.[26]

Lyautey allowed the Sultan to retain his powers, both nominal and practical: He issued decrees in his own name and seal, and was allowed to remain religious leader of Morocco; he was further allowed an all-Arab court. Lyautey once said of this:

In Morocco, there is only one government, the sharifian government, protected by the French.

Walter Burton Harris, a British journalist who wrote extensively on Morocco, commented upon French preservation of traditional Moroccan society:[26]

At the Moorish court, scarcely a European is to be seen, and to the native who arrives at the Capital [sic] there is little or no visible change from what he and his ancestors saw in the past.

Lyautey served his post until 1925, in the late midst of the failed revolt of the Republic of the Rif against Franco-Spanish administration and the Sultan.

Agriculture

Learning from experiences in Algeria, where imprudent land appropriation, as Susan Gilson Miller put it, "reduced much of the native peasantry to a rootless proletariat," Lyautey solicited a select group of 692 "gentlemen-farmers"—instead of what he called the "riff-raff" of southern Europe—capable of serving as "examples" to les indigènes and imparting French influence in the rural colonization of Morocco from 1917 to 1925.[12] The objective was to secure a steady supply of grain for Metropolitan France and to transform Morocco once again into the "granary of Rome" by planting cereals primarily in the regions of Chaouia, Gharb, and Hawz—despite the fact that the region is prone to drought. After a period of minimal profits and a massive locust swarm in 1930, agricultural production shifted toward irrigated, higher-value crops such as citrus fruits and vegetables.[12] The industrialization of agriculture required capital that many Moroccan farmers didn't have, leading to a rural exodus as many headed to find work in the city.[12]

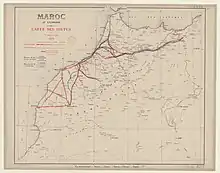

Infrastructure

Compagnie franco-espagnole du chemin de fer de Tanger à Fez built a standard gauge railroad connecting Fes and Tangier,[27] while Compagnie des chemins de fer du Maroc (CFM) built standard gauge railways connecting Casablanca, Kenitra, and Sidi Kacem, and Casablanca and Marrakech, completed in 1928.[28] Compagnie des Chemins de Fer du Maroc Oriental created narrow-gauge railroads east of Fes.[29]

La Compagnie de Transports au Maroc (CTM) was founded 30 November 1919 with the goal of accessing "all of Morocco." Its services ran along a new colonial road system planned with the aim of linking all major towns and cities.[30]

Natural Resources

The Office Chérifien des Phosphates (OCP) was created in 1920 to mine phosphates out of Khouribga, which was connected to the Port of Casablanca by a direct rail line.[30] In 1921, 39,000 tons of phosphate were extracted, while almost 2 million tons were extracted in 1930.[30] The Moroccan laborers working in the mines benefited from no social protections, were forbidden from unionizing, and earned a tiny fraction of what Europeans earned.[30]

Industry

Industry during the early period of the protectorate on focused food processing for local consumption: there were canneries, a sugar refinery (Compagnie Sucriere Marocaine, COSUMA),[31] a brewing company (Société des Brasseries du Maroc, SBM),[32] and flourmills.[33][30] Manufacturing and heavy industry, however, were not embraced for fears of competing with Metropolitan France.[30]

Opposition to French control

Zaian War

The Zaian confederation of Berber tribes in Morocco fought a war of opposition against the French between 1914 and 1921. Resident-General Louis-Hubert Lyautey sought to extend French influence eastwards through the Middle Atlas mountains towards French Algeria. This was opposed by the Zaians, led by Mouha ou Hammou Zayani. The war began well for the French, who quickly took the key towns of Taza and Khénifra. Despite the loss of their base at Khénifra, the Zaians inflicted heavy losses on the French.

With the outbreak of the First World War, France withdrew troops for service in Europe, and they lost more than 600 in the Battle of El Herri. Over the following four years, the French retained most of their territory despite the Central Powers' intelligence and financial support to the Zaian Confederation and continual raids and skirmishes reducing scarce French manpower.

After Armistice with Germany in November 1918, significant forces of tribesmen remained opposed to French rule. The French resumed their offensive in the Khénifra area in 1920, establishing a series of blockhouses to limit the Zaians' freedom of movement. They opened negotiations with Hammou's sons, persuading three of them, along with many of their followers, to submit to French rule. A split in the Zaian Confederation between those who supported submission and those still opposed led to infighting and the death of Hammou in Spring 1921. The French responded with a strong, three-pronged attack into the Middle Atlas that pacified the area. Some tribesmen, led by Moha ou Said, fled to the High Atlas and continued a guerrilla war against the French well into the 1930s.

Rif War

Sultan Yusef's reign, from 1912 to 1927, was turbulent and marked with frequent uprisings against Spain and France. The most serious of these was a Berber uprising in the Rif Mountains, led by Abd el-Krim, who managed to establish a republic in the Rif. Though this rebellion began in the Spanish-controlled area in the north, it reached the French-controlled area. A coalition of France and Spain finally defeated the rebels in 1925. To ensure their own safety, the French moved the court from Fez to Rabat, which has served as the capital ever since.[34]

Nationalist parties

Amid the backlash against the Berber Decree of 16 May 1930, crowds gathered in protest and a national network was established to resist the legislation. Dr. Susan Gilson Miller cites this as the "seedbed out of which the embryonic nationalist movement emerged."[35] In December 1934, a small group of nationalists, members of the newly formed Moroccan Action Committee (كتلة العمل الوطني, Comité d’Action Marocaine – CAM), proposed a Plan of Reforms (برنامج الإصلاحات المغربية) that called for a return to indirect rule as envisaged by the Treaty of Fes, admission of Moroccans to government positions, and establishment of representative councils. The moderate tactics used by the CAM to obtain consideration of reform – including petitions, newspaper editorials, and personal appeals to French.

World War II

During World War II, the badly divided nationalist movement became more cohesive, and informed Moroccans dared to consider the real possibility of political change in the post-war era. The Moroccan Nationalist Movement (الحركة الوطنية المغربية) was emboldened by overtures made by Franklin D. Roosevelt and the United States during the 1943 Anfa Conference during World War II, expressing support for Moroccan independence after the war. Nationalist political parties based their arguments for Moroccan independence on such World War II declarations as the Atlantic Charter.[36]

However, the nationalists were disappointed in their belief that the Allied victory in Morocco would pave the way for independence. In January 1944, the Istiqlal Party, which subsequently provided most of the leadership for the nationalist movement, released a manifesto demanding full independence, national reunification, and a democratic constitution.[37] Sultan Muhammad V had approved the manifesto before its submission to the French resident general Gabriel Puaux, who answered that no basic change in the protectorate status was being considered.[38]

Struggle for Independence

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, with political and nonviolent efforts proving futile, the Moroccan struggle for independence became increasingly violent, with massacres, bombings, and riots, particularly in the urban and industrial center, Casablanca.

Tangier Speech and Casablanca Tirailleurs Massacre

In 1947, Sultan Muhammad V planned to deliver a speech in what was then the Tangier International Zone to appeal for his country's independence from colonialism and for its territorial unity.[39]

In the days leading up to the sultan's speech, French colonial forces in Casablanca, specifically Senegalese Tirailleurs serving the French colonial empire, carried out a massacre of working class Moroccans. The massacre lasted for about 24 hours from 7–8 April 1947, as the tirailleurs fired randomly into residential buildings in working-class neighborhoods, killing 180 Moroccan civilians. The conflict was instigated in an attempt to sabotage the Sultan's journey to Tangier, though after having returned to Casablanca to comfort the families of the victims, the Sultan then proceeded to Tangier to deliver the historic speech, in the garden of the Mendoubia palace.[40][41]

Murder of Farhat Hached

The assassination of the Tunisian labor unionist Farhat Hached by La Main Rouge—the clandestine militant wing of French intelligence—sparked protests in cities around the world and riots in Casablanca from 7–8 December 1952.[42] Approximately 100 people were killed.[43] In the aftermath of the riots, French authorities arrested Abbas Messaadi, who would eventually escape, found the Moroccan Liberation Army, and join the armed resistance in the Rif.[44]

Glaoui's attempted coup

In 1953, Thami El Glaoui attempted to orchestrate a coup against Sultan Muhammad V with the support of the French protectorate.[45] The 1953 Oujda revolt broke out ten days after his "electoral" campaign passed through the city.[46]

Exile of Sultan Muhammad

The general sympathy of the sultan for the nationalists had become evident by the end of the war, although he still hoped to see complete independence achieved gradually. By contrast, the residency, supported by French economic interests and vigorously backed by most of the colonists, adamantly refused to consider even reforms short of independence. Official intransigence contributed to increased animosity between the nationalists and the colonists and gradually widened the split between the sultan and the resident general.

Muhammad V and his family were transferred to Madagascar in January 1954. His replacement by the unpopular Muhammad Ben Aarafa, whose reign was perceived as illegitimate, sparked active opposition to the French protectorate both from nationalists and those who saw the sultan as a religious leader.[47] By 1955, Ben Arafa was pressured to abdicate; consequently, he fled to Tangier where he formally abdicated.[48]

The French executed 6 Moroccan nationalists in Casablanca on 4 January 1955.[49] The aggressions between the colonists and the nationalists increased from 19 August – 5 November 1955, and approximately 1,000 people died[49]

Later on, faced with a united Moroccan demand for the sultan’s return, on a great scale, rising violence in Morocco, and the deteriorating situation in Algeria, Muhammad V was returned from exile on 16 November 1955, and declared independence on 18 November 1955. In February 1956 he successfully negotiated with France to enforce the independence of Morocco, and in 1957 took the title of King.

1956 independence

In late 1955, Muhammad V successfully negotiated the gradual restoration of Moroccan independence within a framework of French-Moroccan interdependence. The sultan agreed to institute reforms that would transform Morocco into a constitutional monarchy with a democratic form of government. In February 1956, Morocco acquired limited home rule. Further negotiations for full independence culminated in the French-Moroccan Agreement signed in Paris on 2 March 1956.[50][51] On 7 April of that year France officially relinquished its protectorate in Morocco. The internationalized city of Tangier was reintegrated with the signing of the Tangier Protocol on 29 October 1956.[52] The abolition of the Spanish protectorate and the recognition of Moroccan independence by Spain were negotiated separately and made final in the Joint Declaration of April 1956.[53] Through these agreements with Spain in 1956 and 1958, Moroccan control over certain Spanish-ruled areas was restored, though attempts to claim other Spanish possessions through military action were less successful.

In the months that followed independence, Muhammad V proceeded to build a modern governmental structure under a constitutional monarchy in which the sultan would exercise an active political role. He acted cautiously, having no intention of permitting more radical elements in the nationalist movement to overthrow the established order. He was also intent on preventing the Istiqlal Party from consolidating its control and establishing a one-party state. In August 1957, Muhammad V assumed the title of king.

Monetary policy

The French minted coinage for use in the Protectorate from 1921 until 1956, which continued to circulate until a new currency was introduced. The French minted coins with denomination of francs, which were divided into 100 centimes. This was replaced in 1960 with the reintroduction of the dirham, Morocco's current currency.

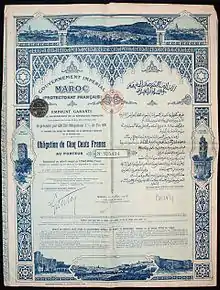

The Algeciras Conference gave concessions to the European bankers, ranging from a newly formed State Bank of Morocco, to issuing banknotes backed by gold, with a 40-year term. The new state bank was to act as Morocco's Central Bank, but with a strict cap on the spending of the Sherifian Empire, with administrators appointed by the national banks that guaranteed the loans: the German Empire, United Kingdom, France and Spain.[54]

Repression

Hubert Lyautey established the Native Policy Council (Conseil de politique indigène),[55] which oversaw colonial rule in the protectorate.

Under the protectorate, Moroccans were prevented from attending large political gatherings.[56] This was because colonial forces deemed they might "hear things beyond their capacity to understand."[56][57]

French authorities also forbade Arabic-language newspapers from covering politics, which sparked claims of censorship.[56] Under the French protectorate, entire articles were censored from the Istiqlal Party's Arabic Al-Alam newspaper, which was printed with blocks of missing text.[58]

Postal history

A French postal agency had sent mail from Tangier as early as 1854,[59] but the formal beginning of the system was in 1892, when the Sultan of Morocco Hassan the first established the first organized state owned postal service called Sharifan post, by opening several post offices throughout the country.[60] This initiative aimed to limit the foreign or local private postal services. After the establishment of the protectorate in 1912, the offices issued postage stamps of France surcharged with values in pesetas and centimos, at a 1–1 ratio with the denominations in French currency, using both the Type Sage issues, and after 1902, Mouflon issue inscribed "MAROC" (which were never officially issued without the surcharge). In 1911, the Mouflon designs were overprinted in Arabic.

The first stamps of the protectorate appeared 1 August 1914, and were just the existing stamps with the additional overprint reading "PROTECTORAT FRANCAIS".[61] The first new designs were in an issue of 1917, consisting of 17 stamps in six designs, denominated in centimes and francs, and inscribed "MAROC".

Railways

Morocco had from 1912–1935 one of the largest 600 mm (1 ft 11+5⁄8 in) gauge networks in Africa with total length of more than 1,700 kilometres.[62] After the treaty of Algeciras where the representatives of Great Powers agreed not to build any standard gauge railway in Morocco until the standard gauge Tangier–Fez Railway being completed, the French had begun to build military 600 mm (1 ft 11+5⁄8 in) gauge lines in their part of Morocco.

Legacy

French colonialism had a lasting impact on society, economy, language, culture, and education in Morocco. There are also lingering connections that have been described as neocolonial.[63][64] As a francophone former colony of France in Africa, Morocco falls into the cadre of Françafrique and la Francophonie.[65] In 2019, 35% of Moroccans speak French—more than Algeria at 33%, and Mauritania at 13%.[66]

There are approximately 1,514,000 Moroccans in France, representing the largest community of Moroccans outside of Morocco.[67] The INSEE announced that there are approximately 755,400 Moroccan nationals residing in France as of October 2019, representing 20% of France's immigrant population.[68]

The former Residence-general, designed for Lyautey by architect Albert Laprade and completed in 1924, is now the seat of the Moroccan Ministry of Interior.

See also

- French conquest of Morocco

- List of French residents-general in Morocco

- Spanish protectorate in Morocco

- History of Morocco

- France–Morocco relations

- French protectorate of Tunisia

- French Algeria

- List of French possessions and colonies

References

- "Mohammed VI", whose real name was Mohammed Ben Aarafa, was put in place by the French after his predecessor was ousted by them but was not recognized in the Spanish-protected part of Morocco

- Bulletin officiel de l'Empire chérifien, vol. 4, no 162, 29 November 1915, p. 838

- Miller, Susan Gilson (15 April 2013). A History of Modern Morocco. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521810708 – via Google Books.

- Miller, Susan Gilson (15 April 2013). A History of Modern Morocco. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521810708 – via Google Books.

- "National Holidays & Religious Holidays". Maroc.ma. 4 October 2013.

- Miller, Susan Gilson. (2013). A history of modern Morocco. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-62469-5. OCLC 855022840.

- "Indépendance du Maroc, 1956, MJP". mjp.univ-perp.fr. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- Ikeda, Ryo (December 2007). "The Paradox of Independence: The Maintenance of Influence and the French Decision to Transfer Power in Morocco". The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. 35 (4): 569–592. doi:10.1080/03086530701667526. S2CID 153965067.

- Furlong, Charles Wellington (September 1911). "The French Conquest Of Morocco: The Real Meaning Of The International Trouble". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. XXII: 14988–14999. Retrieved 10 July 2009.

- Laskier, Michael M. (1 February 2012). Alliance Israelite Universelle and the Jewish Communities of Morocco, 1862–1962, The. SUNY Press. p. 41. ISBN 9781438410166.

- Lowe, John (1994). The Great Powers, Imperialism, and the German Problem, 1865–1925. Psychology Press. p. 166. ISBN 9780415104449.

- Olson, James Stuart (1991). Historical Dictionary of European Imperialism. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 8. ISBN 9780313262579.

- Miller, Susan Gilson. (2013). A history of modern Morocco. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 75. ISBN 9781139624695. OCLC 855022840.

- Adam, André (1968). Histoire de Casablanca: des origines à 1914. Aix-en-Provence: Ophrys.

- Adam, André (1969). "Sur l'action du Galilée à Casablanca en août 1907". Revue des mondes musulmans et de la Méditerranée. 6 (1): 9–21. doi:10.3406/remmm.1969.1002.

- texte, Parti social français Auteur du (6 August 1907). "Le Petit journal". Gallica. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- Fikrat al-dustūr fī al-Maghrib: wathāʼiq wa-nuṣūṣ (1901–2011) (Buch, 2017) [WorldCat.org]. 11 April 2020. OCLC 994641823. Archived from the original on 11 April 2020. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- "جريدة "السعادة" التي كانت لسانا ناطقا باسم الاحتلال الفرنسي في المغرب". هوية بريس (in Arabic). 15 May 2015. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- Kirshner, Jonathan (1997). Currency and Coercion: The Political Economy of International Monetary Power. Princeton University Press. p. 83. ISBN 0691016267.

- "TRAITÉ conclu entre la France et le Maroc le 30 mars 1912, pour l'Organisation du Protectorat Français dans l'Empire Chérifien" (PDF). Bulletin officiel de l'Empire chérifien (in French). Rabat. 1 (1): 1–2. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- H. Z(J. W.) Hirschberg (1981). A history of the Jews in North Africa: From the Ottoman conquests to the present time / edited by Eliezer Bashan and Robert Attal. BRILL. p. 318. ISBN 90-04-06295-5.

- "Segalla, Spencer 2009,The Moroccan Soul: French Education, Colonial Ethnology, and Muslim Resistance, 1912–1956. Nebraska University Press".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Bengt Brons, "States: The classification of States", in: International Law: Achievements and Prospects, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers 1991 (ISBN 9789231027161), p.51 §.31

- "Exhibition of Moroccan Art". www.wdl.org. 1917. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- الأشرف, الرباط ــ حسن. "الجنود المغاربة في الحرب العالمية الأولى: أبطال بلا مجد". alaraby (in Arabic). Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- "Guerre de 1914–18: les soldats marocains "dans toutes les grandes batailles"". LExpress.fr (in French). 1 November 2018. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- "A History of Modern Morocco" p.90-91 Susan Gilson Miller, Cambridge University Press 2013

- Compagnie franco-espagnole du chemin de fer de Tanger à Fez. 1914.

- "La Terre marocaine: revue illustrée..." Gallica. 1 December 1928. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- Allain, J.-C. (1987). "Les chemins de fer marocains du protectorat français pendant l'entre-deux-guerres". Revue d'Histoire Moderne & Contemporaine. 34 (3): 427–452. doi:10.3406/rhmc.1987.1417.

- Miller, Susan Gilson (8 April 2013). A History of Modern Morocco. Cambridge University Press. p. 112. ISBN 9781139619110.

- "HISTORY". Cosumar. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- "History – GBM". Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- Vassal, Serge (1951). "Les industries de Casablanca". Les Cahiers d'Outre-Mer. 4 (13): 61–79. doi:10.3406/caoum.1951.1718.

- Lepage, Jean-Denis G. G. (27 November 2007). The French Foreign Legion: An Illustrated History. McFarland. p. 125. ISBN 9780786462537.

- Miller, Susan Gilson. (2013). A history of modern Morocco. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 129. ISBN 9781139624695. OCLC 855022840.

- Africa, Unesco International Scientific Committee for the Drafting of a General History of (1990). Africa Under Colonial Domination, 1880–1935. Currey. p. 268. ISBN 9780852550977.

- الاستقلال, Istiqlal Maroc Parti-حزب. "Manifeste de l'indépendance du 11 Janvier 1944". Portail du Parti de l'Istiqlal Maroc (in French). Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- Zisenwine, Daniel (30 September 2010). Emergence of Nationalist Politics in Morocco: The Rise of the Independence Party and the Struggle Against Colonialism After World War II. I.B.Tauris. p. 39. ISBN 9780857718532.

- "زيارة محمد الخامس لطنجة.. أغضبت فرنسا وأشعلت المقاومة". Hespress (in Arabic). 31 July 2013. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- Atlasinfo (6 April 2016). "Evènements du 7 avril 1947 à Casablanca, un tournant décisif dans la lutte pour la liberté et l'indépendance". Atlasinfo.fr: l'essentiel de l'actualité de la France et du Maghreb (in French). Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- Revisiting the colonial past in Morocco. Maghraoui, Driss. London: Routledge. 2013. p. 151. ISBN 9780415638470. OCLC 793224528.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Yabiladi.com. "7–8 décembre 1952: Quand les Casablancais se sont soulevés contre l'assassinat de Ferhat Hached". www.yabiladi.com (in French). Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- "6. French Morocco (1912–1956)". uca.edu. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- "L'assassinat de Messaâdi". Zamane (in French). 12 November 2012. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- البطيوي, توفيق. "التهامي الكلاوي.. صفحة سوداء في تاريخ المغرب الحديث". www.aljazeera.net (in Arabic). Retrieved 28 September 2022.

في التاسع عشر من ماي 1953 أصدر الباشا الكلاوي بيانا معلنا فيه صداقته وإخلاصه للحماية الفرنسية مطالبا إياها بإبعاد السلطان محمد الخامس

- "Quatre-vingt-seize Marocains poursuivis pour participation à la « tuerie d'Oujda », qui fit trente morts le 16 août 1953, passent en jugement". Le Monde.fr (in French). 30 November 1954. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- Lentz, Harris M. (4 February 2014). Heads of States and Governments Since 1945. Routledge. p. 558. ISBN 9781134264902.

- Lawless, Richard I.; Findlay, Allan (15 May 2015). North Africa (RLE Economy of the Middle East): Contemporary Politics and Economic Development. Routledge. p. 67. ISBN 9781317592983.

- "6. French Morocco (1912–1956)". uca.edu. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- "Déclaration commune" (in French). Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Development (France). 2 March 1956.

- "French-Moroccan Declaration". Department of State Bulletin. Department of State. XXXIV (873): 466–467. 19 March 1956. (unofficial translation)

- "Final Declaration of the International Conference in Tangier and annexed Protocol. Signed at Tangier, on 29 October 1956 [1957] UNTSer 130; 263 UNTS 165". 1956.

- "Spanish-Moroccan Declaration". Department of State Bulletin. Department of State. XXXIV (878): 667–668. 23 April 1956. (unofficial translation)

- Holmes, James R. (29 May 2017). Theodore Roosevelt and World Order: Police Power in International Relations. Potomac Books, Inc. p. 199. ISBN 9781574888836.

- texte, France coloniale moderne Auteur du (2 March 1922). "Les Annales coloniales: organe de la "France coloniale moderne" / directeur: Marcel Ruedel". Gallica (in French). Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- Miller, Susan Gilson. (2013). A history of modern Morocco. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 124. ISBN 9781139624695. OCLC 855022840.

- Hoisington, William A. Jr. (1 March 2000). "Designing Morocco's future: France and the Native Policy Council, 1921–25". The Journal of North African Studies. 5 (1): 63–108. doi:10.1080/13629380008718388. ISSN 1362-9387. S2CID 143725817.

- Bitton, Simone, (1955– ...)., Réalisateur / Metteur en scène / Directeur (2010), Ben Barka l'équation marocaine, L'Harmattan vidéo [éd., distrib.], ISBN 978-2-296-10925-4, OCLC 690860373, retrieved 6 July 2021

- The Collectors Club Philatelist. Collectors Club. 1948. p. 23.

- Gottreich, Emily (2007). The Mellah of Marrakesh: Jewish and Muslim Space in Morocco's Red City. Indiana University Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0253218636.

- The New England Philatelist. Essex Publishing Company. 1914. p. 336.

- Rogerson, Barnaby (2000). Marrakesh, Fez, Rabat. New Holland Publishers. p. 12. ISBN 9781860119736.

- Zakhir, Marouane; O’Brien, Jason L. (1 February 2017). "French neo-colonial influence on Moroccan language education policy: a study of current status of standard Arabic in science disciplines". Language Policy. 16 (1): 39–58. doi:10.1007/s10993-015-9398-3. ISSN 1573-1863.

- "France summons Italian envoy after Di Maio's comments on Africa". Reuters. 21 January 2019. Archived from the original on 24 January 2019. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- "50 years later, Françafrique is alive and well". RFI. 16 February 2010. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- Koundouno, Tamba François (20 March 2019). "International Francophonie Day: 35% Moroccans Speak French". Morocco World News. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- Fiches thématiques – Population immigrée – Immigrés – Insee Références – Édition 2012, Insee 2012 Archived 13 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Hekking, Morgan (9 October 2019). "Moroccans Make Up Nearly 20% of France's Immigrant Population". Morocco World News. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

Further reading

- Gershovich, Moshe (2000). French Military Rule in Morocco: colonialism and its consequences. Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-4949-X.

- Roberts, Stephen A. History of French Colonial Policy 1870-1925 (2 vol 1929) vol 2 pp 545–90 online

- Bensoussan, David (2012). Il était une fois le Maroc: témoignages du passé judéo-marocain. iUniverse. ISBN 978-1-4759-2608-8.