Görlitz

Görlitz ([ˈɡœʁlɪts] (![]() listen); Polish: Zgorzelec, Upper Sorbian: Zhorjelc, Czech: Zhořelec, East Lusatian dialect: Gerlz, Gerltz, Gerltsch[3][4]) is a town in the German state of Saxony. It is located on the Lusatian Neisse River, and is the largest town in Upper Lusatia as well as the second-largest town in the region of Lusatia, after Cottbus. Görlitz is the easternmost town in Germany (easternmost village is Zentendorf (Šćeńc)), and lies opposite the Polish town of Zgorzelec, which was the eastern part of Görlitz until 1945. The town has approximately 56,000 inhabitants, which make Görlitz the sixth-largest town in Saxony. It is the seat of the district of Görlitz. Together with Zgorzelec, it forms the Euro City of Görlitz/Zgorzelec, which has a combined population of around 86,000. While not Lusatiophone itself, the town is situated just east of the Sorbian-speaking parts of Lusatia.

listen); Polish: Zgorzelec, Upper Sorbian: Zhorjelc, Czech: Zhořelec, East Lusatian dialect: Gerlz, Gerltz, Gerltsch[3][4]) is a town in the German state of Saxony. It is located on the Lusatian Neisse River, and is the largest town in Upper Lusatia as well as the second-largest town in the region of Lusatia, after Cottbus. Görlitz is the easternmost town in Germany (easternmost village is Zentendorf (Šćeńc)), and lies opposite the Polish town of Zgorzelec, which was the eastern part of Görlitz until 1945. The town has approximately 56,000 inhabitants, which make Görlitz the sixth-largest town in Saxony. It is the seat of the district of Görlitz. Together with Zgorzelec, it forms the Euro City of Görlitz/Zgorzelec, which has a combined population of around 86,000. While not Lusatiophone itself, the town is situated just east of the Sorbian-speaking parts of Lusatia.

Görlitz | |

|---|---|

Clockwise from top: St Peter and Paul Church; Upper Lusatian Library of Sciences; towers of Görlitz: city hall, Trinity Church, Reichenbach Tower and Luther Church; view over the city to Landeskrone Mountain; Görlitz Department Store; Lower Market Square with the city hall | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

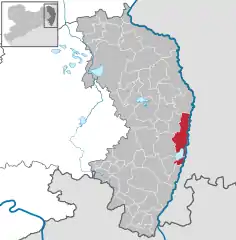

Location of Görlitz within Görlitz district  | |

Görlitz  Görlitz | |

| Coordinates: 51°09′10″N 14°59′14″E | |

| Country | Germany |

| State | Saxony |

| District | Görlitz |

| Subdivisions | 9 town- and 8 village-quarters |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (2019–26) | Octavian Ursu[1] (CDU) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 67.52 km2 (26.07 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 199 m (653 ft) |

| Population (2020-12-31)[2] | |

| • Total | 55,784 |

| • Density | 830/km2 (2,100/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| Postal codes | 02826–02828 |

| Dialling codes | 03581 |

| Vehicle registration | GR |

| Website | www |

The town's recorded history began in the 11th century as a Sorbian settlement. Through its history, it has been under German, Czech (Bohemian), Polish and Hungarian rule. From 1815 until 1918, Görlitz belonged to the Province of Silesia in the Kingdom of Prussia, and later to the Province of Lower Silesia in the Free State of Prussia — it was the Silesian provinces' largest town west of the Oder-Neisse line, and hence Görlitz became part of East Germany from 1949 until German reunification in 1990.

Görlitz is culturally diverse. While it is a town of Saxony, its inhabitants also identify as Upper Lusatian. The East Lusatian dialect (Ostlausitzer Mundart) of the town differs from the Upper Saxon dialects spoken in most parts of Saxony, especially those of Dresden and Leipzig. And because the town had been integrated into the former provinces of Silesia and later Lower Silesia respectively, there is also a strong Silesian element in the city's culture, which is reflected by the presence of some Silesian dishes like Schlesisches Himmelreich or Liegnitzer Bombe, a Silesian Museum (Schlesisches Museum zu Görlitz), or the Silesian Christmas Market (Schlesischer Christkindelmarkt). Additionally, there is the Sorbian element, as Görlitz was founded and first settled by the Sorbs, a Slavic people. This is most obvious in that the name of the town and the etymology of some of its incorporated villages and geographic features are of Slavic origin.

Spared from the destruction of World War II, the town also has a rich architectural heritage. Many movie-makers have used the various sites as filming locations.[5]

History

Middle Ages

In the Early Middle Ages, the area was inhabited by the Bieżuńczanie tribe,[6] one of the old Polish tribes.[7] The nearby Landeskrone mountain, as Businc, is considered the main stronghold of the tribe,[6] while Gorelic was a small village. Together with the Sorbian Milceni tribe, with which they bordered in the west, they were subjugated in 990 by the Margraviate of Meissen, a frontier march of the Holy Roman Empire. The settlement was then conquered by Polish ruler Bolesław I Chrobry in 1002, and then formed part of the Duchy of Poland (kingdom from 1025) until 1031, when the region fell back to the Margraviate of Meissen. In 1075, the village was assigned to the Duchy of Bohemia. The date of the town's foundation is unknown. However, Goreliz was first mentioned in a document from the King of Germany, and later Holy Roman Emperor, Henry IV in 1071. This document granted Görlitz to the Diocese of Meissen, then under Bishop Benno of Meissen. Currently, this document can be found in the Saxony State Archives in Dresden.[8] The origin of the name Görlitz is derived from the Slavic word for "burned land",[9] referring to the technique used to clear land for settlement. Zgorzelec and Czech Zhořelec have the same derivation. In 1126–1131, Bohemian Duke Soběslav I erected a castle, one of several new castles on the Bohemian-Polish border. It was probably located at the site of the present St. Peter and Paul church. In the 13th century the village gradually became a town. Due to its location on the Via Regia, an ancient and medieval trade route, the settlement prospered.

In 1319 it became part of the Piast-ruled Duchy of Jawor, the southwesternmost duchy of fragmented Poland, and Duke Henry I of Jawor confirmed the town's privileges.[10] Later on, the town fell back to Bohemia. From 1346 Görlitz was a wealthy member of the Lusatian League, which consisted of Bautzen, Görlitz, Kamenz, Lubań, Löbau and Zittau.[11] Around 1348 a Jewish woman, Adasse, was made a citizen of the town.[12] In 1352 during the reign of King Casimir III the Great, Lusatian German colonists from Görlitz founded the town of Gorlice in southern Poland near Kraków. From 1377 to 1396 it was the capital of an eponymous duchy.[13] In 1469, along with the Lusatian League, the town recognized the rule of King Matthias Corvinus, thus passing to Hungarian rule, and in 1490 it fell back to Bohemia then ruled by Polish prince Vladislaus Jagiellon.[11]

Modern period

The Protestant Reformation came to Görlitz in the early 1520s and by the last half of the 16th century, it and the surrounding vicinity, became almost completely Lutheran.

During the Thirty Years' War, in 1623, the town was captured and occupied alternately by Sweden and the Holy Roman Empire.[13] In 1635, the region of Upper Lusatia (including Görlitz) was ceded to the Electorate of Saxony. From 1639, the town was occupied by Sweden again, and then it was besieged by Imperial and Saxon forces in 1641.[13] After the war, it was part of the Electorate of Saxony, from 1697 within the Polish–Saxon personal union. One of two main routes connecting Warsaw and Dresden ran through the town in the 18th century and Kings Augustus II the Strong and Augustus III of Poland often traveled that route.[14] Napoleon visited the town several times in 1807, 1812 and 1813. After the Napoleonic Wars, the 1815 Congress of Vienna transferred the town from the Kingdom of Saxony to the Kingdom of Prussia. Görlitz was subsequently administered within the Province of Silesia, and, after World War I, the Province of Lower Silesia, until 1945. During World War I, an internment camp for Greek soldiers was located in present-day Zgorzelec, while 500 Greek officers lived in private quarters throughout the town.[15] A burial ground for Greek soldiers was located at the local cemetery.[15]

Shortly after the Nazi Party's rise to power, in March 1933, the SA established the Leschwitz concentration camp in Leschwitz (present-day district of Weinhübel).[16] Political prisoners were held and tortured in the camp, before it was dissolved in August 1933, and the prisoners were deported to other concentration camps.[16] In 1936, during a nationwide Nazi campaign of changing of placenames, two present-day districts of Görlitz were renamed to erase traces of Slavic origin—Leschwitz to Weinhübel and Nikrisch to Hagenwerder.[17][18] During Kristallnacht in November 1938, an arson attack was carried out on the city's synagogue. However, the building survived the attack without major damage, because firefighters resisted the order not to extinguish the fire.[19] It is the only one synagogue in the present state of Saxony that survived Nazi rule.[20] In the interwar period, most of the Jews left the city, and their number dropped from 567 in 1925 to 134 in 1939.[21] Many remaining Jews were then killed in the Holocaust during World War II.[20]

During World War II, a Nazi prison was operated in the town, with four forced labour subcamps within the town limits and three in nearby villages.[22] The Nazis also established and operated two subcamps of the Gross-Rosen concentration camp, located in present-day districts of Biesnitz and Kunnerwitz, in which over 1,500 Jewish men and women were used as forced labour, and 470 of whom died.[23] Numerous subcamps of the Stalag VIII-A prisoner-of-war camp were located in the town, in which over 10,000 POWs worked as forced labour in 1942, and one of the largest subcamps was located in nearby Weinhübel (district of Görlitz since 1949).[24] After the Soviet offensive of 1944 and the partial evacuation of the German court staff from the General Government in German-occupied Poland, a special court of the General Government was established at the local courthouse.[25] Several Polish citizens were detained in Görlitz and sentenced to prison or death at this court for rescuing Jews from the Holocaust.[26]

Near the end of World War II, German troops destroyed all bridges crossing the Lusatian Neisse. The redrawing of boundaries in 1945—in particular the location of the East German-Polish border to the present Oder-Neisse line—divided the town. The right bank became part of Poland and was initially renamed Zgorzelice, and then Zgorzelec in 1948, with both names being historically used in the Polish language,[13][27][28] while the main portion on the left bank became part of East Germany, now within the state of Saxony.

On 12 June 1945, the city issued a set of four of its own postage stamps.

German Democratic Republic and Reunited Germany

When the East German states were dissolved in 1952, Görlitz became part of the Dresden District, but the states were restored upon German reunification in 1990. In 1972, the East German-Polish border was opened for visa-free travel, resulting in intense movement between Görlitz and Zgorzelec, which lasted until 1980, when East Germany unilaterally closed the border due to anti-communist protests and the emergence of the Solidarity movement in Poland. On 27 June 1994, the town became the seat of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Görlitz, but it remains a Lutheran Protestant stronghold.

In 2002 Lake Berzdorf, occupying a former open-cast lignite mine south of Görlitz, began to be filled. The Altstadtbrücke (literally old town bridge) between Görlitz and sister city Zgorzelec was rebuilt between 2003 and 2004. It was officially opened on 20 October 2004. As soon as Poland signed the Schengen Agreement (20 December 2007), movement between the two banks of the river again became unrestricted, since border controls were eliminated. Indeed, users of the new pedestrian bridge are not told by any signs that they are leaving one country and entering another.

Since reunification, and as of 2013, over 700 buildings have been renovated. It is a popular place for retirement among the elderly of Germany, being quiet and relatively affordable by German standards.[29] Its tourist potential is rapidly expanding, being very much an eastern counterpart to towns such as Heidelberg. In the case of Görlitz, much of the funding for the renovations of the town's buildings have come from an anonymous donor, who, from 1995 onward, has sent an annual donation of over €500,000, totalling over €10,000,000.[30]

In 2021, the surviving old synagogue was reopened.[20]

Arts and culture

_01(js).jpg.webp)

Today Görlitz and Zgorzelec, two towns on opposite banks of the narrow river, get along well. Two bridges have been rebuilt, a bus line connects the German and Polish parts of the town, and there is a common urban management, with annual joint sessions of both town councils.

The town has a rich architectural heritage (Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque, Neoclassical, Art Nouveau). One example of this rich architectural heritage is the Schönhof, which is one of the oldest civic Renaissance buildings in Germany. Another medieval heritage is a model of the Holy Sepulchre (de) whose construction began in 1465 under Bürgermeister Georg Emmerich.[31]

In 2006 the twin city Görlitz/Zgorzelec applied to be the European City of Culture 2010. It was hoped that the concept of Polish-German cooperation would be sufficient to convince the jury, but Essen won. Görlitz was placed second. As a result of the campaign Görlitz was renamed City of Culture in order to further German-Polish relations and to attract tourists from all over the world.[32]

As Görlitz was part of Silesia from 1815 onward, it has a Silesian Museum dedicated to the region (Schlesisches Museum zu Görlitz). The exhibition features the 1000-year-old cultural history of Silesia.

Görlitz is also the birthplace of the German version of nonpareils, popularly known in Germany as Liebesperlen (German: love pearls). Invented by confectioner Rudolf Hoinkis (1876–1944), the name derives from a conversation Hoinkis had with his wife, proclaiming his love for her like these "pearls", the nonpareil. Unsure of what to call the treat he invented, his wife suggested calling them love pearls, and the name stuck. The factory where he first manufactured the treat, founded in 1896, is now run by his great-grandson, Mathias.[33]

Geography

Görlitz is situated on the border with Poland, adjacent to the Polish town of Zgorzelec on the opposite bank of the Lusatian Neisse. The municipality measures 19.4 km (12.1 mi) from north to south, and 7.3 km (4.5 mi) from east to west.[34] Its area is 67.52 km2 (26.07 sq mi).[35]

Divisions

Görlitz is divided into 9 Stadtteile (town divisions) and 8 Ortsteile (formerly independent municipalities). These are:[34]

- Stadtteile: Historische Altstadt, Innenstadt, Nikolaivorstadt, Südstadt, Rauschwalde, Biesnitz, Weinhübel, Königshufen and Klingewalde

- Ortsteile: Ober-Neundorf, Ludwigsdorf, Schlauroth, Kunnerwitz, Klein Neundorf, Deutsch-Ossig, Hagenwerder and Tauchritz

Transport

Görlitz station is on the Berlin – Görlitz and the Dresden – Görlitz lines of Deutsche Bahn. The station also provides an international connection to Wrocław, Poland.

Local public transport is provided by:

Climate

The climate is oceanic (Köppen: Cfb) or on the western edge of humid continental (Dfb) at the 0 °C isotherm. The location at the easternmost border of Germany, far from the sea, gives a climate less affected by prevailing westerly winds although these do reach further into the western half of Poland. Summers can be warm, though not as much as in Southern Europe, and the winters are cold; snow is sporadic, not persisting all winter.[38]

| Climate data for Görlitz, 1981–2010 normals | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 1.8 (35.2) |

3.1 (37.6) |

7.6 (45.7) |

13.5 (56.3) |

18.7 (65.7) |

21.2 (70.2) |

23.7 (74.7) |

23.4 (74.1) |

18.4 (65.1) |

13.1 (55.6) |

6.5 (43.7) |

2.6 (36.7) |

12.8 (55.1) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −3.2 (26.2) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

0.5 (32.9) |

3.7 (38.7) |

8.1 (46.6) |

11.1 (52.0) |

13.1 (55.6) |

12.8 (55.0) |

9.6 (49.3) |

5.7 (42.3) |

1.5 (34.7) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

4.9 (40.8) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 45.7 (1.80) |

37.3 (1.47) |

49.2 (1.94) |

40.0 (1.57) |

57.6 (2.27) |

65.8 (2.59) |

86.6 (3.41) |

80.0 (3.15) |

53.4 (2.10) |

40.3 (1.59) |

49.2 (1.94) |

50.7 (2.00) |

655.8 (25.83) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 62.8 | 78.8 | 120.9 | 179.2 | 223.6 | 210.5 | 228.2 | 220.3 | 152.7 | 124.9 | 62.9 | 50.1 | 1,714.9 |

| Source: Météoclimat | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Görlitz (near the Goerlitz Airstrip), elevation: 238 m, 1961-1990 normals and extremes | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 14.3 (57.7) |

15.9 (60.6) |

22.5 (72.5) |

30.2 (86.4) |

30.0 (86.0) |

32.7 (90.9) |

35.7 (96.3) |

34.0 (93.2) |

32.1 (89.8) |

26.0 (78.8) |

18.4 (65.1) |

15.3 (59.5) |

35.7 (96.3) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 0.9 (33.6) |

2.7 (36.9) |

7.1 (44.8) |

12.6 (54.7) |

18.0 (64.4) |

21.2 (70.2) |

22.8 (73.0) |

22.6 (72.7) |

18.6 (65.5) |

13.3 (55.9) |

6.5 (43.7) |

2.5 (36.5) |

12.4 (54.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −1.5 (29.3) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

3.2 (37.8) |

7.6 (45.7) |

12.6 (54.7) |

15.8 (60.4) |

17.3 (63.1) |

16.9 (62.4) |

13.6 (56.5) |

9.2 (48.6) |

3.9 (39.0) |

0.2 (32.4) |

8.2 (46.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −4.0 (24.8) |

−3.1 (26.4) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

3.3 (37.9) |

7.6 (45.7) |

10.9 (51.6) |

12.4 (54.3) |

12.0 (53.6) |

9.5 (49.1) |

5.8 (42.4) |

1.5 (34.7) |

−2.1 (28.2) |

4.5 (40.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −27.5 (−17.5) |

−23.7 (−10.7) |

−18.2 (−0.8) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

0.2 (32.4) |

4.8 (40.6) |

4.1 (39.4) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

−14.7 (5.5) |

−21.0 (−5.8) |

−27.5 (−17.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 47.0 (1.85) |

37.0 (1.46) |

38.0 (1.50) |

50.0 (1.97) |

66.0 (2.60) |

70.0 (2.76) |

70.0 (2.76) |

74.0 (2.91) |

52.0 (2.05) |

45.0 (1.77) |

51.0 (2.01) |

57.0 (2.24) |

657 (25.88) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 10.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 9.0 | 7.0 | 10.0 | 12.0 | 116 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 55.8 | 76.0 | 120.8 | 157.5 | 213.8 | 210.5 | 221.7 | 209.7 | 153.6 | 126.8 | 57.9 | 45.1 | 1,649.2 |

| Source: NOAA[39] | |||||||||||||

Film location

Due to the historical parts of the city, many movie-makers have used the various sites as locations. Eli Roth shot the movie-in-a-movie Stolz der Nation (Pride of the Nation) for Quentin Tarantino's Inglourious Basterds (which incidentally purports to be France) on the Lower Market Square and Upper Market Square in Görlitz' oldest parts of the city.[40][41] Other films shot in Görlitz include the 2013 war drama The Book Thief and the teen years in The Reader. Görlitz was used as the primary shooting location for the Wes Anderson film The Grand Budapest Hotel, with Görlitz standing in for a resort in the fictional Eastern European country of Zubrowka. A vacant department store in the city was redecorated to serve as the hotel itself.[42]

Governance

Mayor and city council

The first freely elected mayor after German reunification was Matthias Lechner of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), who served from 1990 to 1998. The mayor was originally chosen by the city council, but since 1994 has been directly elected. Rolf Karbaum served from 1998 until 2005, Joachim Paulick from 2005 to 2012, and Siegfried Deinege from 2012 to 2019; all were independents. In 2019, CDU politician Octavian Ursu was elected mayor. The most recent mayoral election was held on 26 May 2019, with a runoff held on 16 June, and the results were as follows:

| Candidate | Party | First round | Second round | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Votes | % | |||

| Sebastian Wippel | Alternative for Germany | 9,710 | 36.4 | 11,390 | 44.8 | |

| Octavian Ursu | Christian Democratic Union | 8,077 | 30.3 | 14,043 | 55.2 | |

| Franziska Schubert | Green / BfG / MG / SPD / PARTEI | 7,436 | 27.9 | |||

| Jana Lübeck | The Left | 1,470 | 5.5 | |||

| Valid votes | 26,693 | 98.7 | 25,433 | 98.6 | ||

| Invalid votes | 339 | 1.3 | 370 | 1.4 | ||

| Total | 27,032 | 100.0 | 25,803 | 100.0 | ||

| Electorate/voter turnout | 46,120 | 58.6 | 46,135 | 55.9 | ||

| Source: Wahlen in Sachsen | ||||||

The most recent city council election was held on 26 May 2019, and the results were as follows:

| Party | Votes | % | +/- | Seats | +/- | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative for Germany (AfD) | 23,603 | 30.7 | New | 13 | New | |

| Christian Democratic Union (CDU) | 16,896 | 22.0 | 9 | |||

| Citizens for Görlitz (BfG) | 13,397 | 17.5 | 8 | |||

| The Left (Die Linke) | 6,516 | 8.5 | 3 | |||

| Alliance 90/The Greens (Grüne) | 5,847 | 7.6 | 2 | |||

| Motor Görlitz (MG) | 4,347 | 5.7 | New | 2 | New | |

| Social Democratic Party (SPD) | 1,782 | 2.3 | 1 | |||

| Down to Business! (ZS) | 1,729 | 2.3 | 0 | |||

| Free Democratic Party (FDP) | 1,663 | 2.2 | 0 | |||

| BI Seensucht | 604 | 0.8 | New | 0 | New | |

| National Democratic Party (NPD) | 376 | 0.5 | 0 | |||

| Valid votes | 26,530 | 98.0 | ||||

| Invalid votes | 544 | 2.0 | ||||

| Total | 27,074 | 100.0 | 42 | ±0 | ||

| Electorate/voter turnout | 46,119 | 58.7 | ||||

| Source: Wahlen in Sachsen | ||||||

Twin towns – sister cities

Being the easternmost town in the country, Görlitz has formed a "Compass Alliance" (Zipfelbund) with the northernmost, westernmost, and southernmost towns, List, Selfkant, and Oberstdorf respectively. They participate in the annual German Unity Day celebrations to represent the modern limits of Germany.[44]

Notable people

- Michael Ballack (born 1976), football player

- Jakob Böhme (1575–1624), mystic and theologian

- Johann Christoph Brotze (1742–1823), educator

- Hans Georg Dehmelt (1922–2017), co-recipient of 1989 Nobel Prize in Physics

- Hans-Jürgen Dörner (born 1951), football player and coach

- Werner Finck (1902–1978), comedian, actor and writer

- Richard Foerster (classical scholar) (1843–1922), classical scholar

- Johann Carl Gehler (1732–1796) physician, anatomist and mineralogist

- Johann Gottlob Harrer (1703–1755), composer

- Clara Hepner (1860-1939), German-Jewish writer

- Torsten Gütschow (born 1962), football player

- Herbert Hirche (1910–2002), architect and designer

- Hanna von Hoerner (1942–2014), astrophysicist

- Emil Jannings (1884–1950), first actor to win the Academy Award for Best Actor

- Jens Jeremies (born 1974), football player

- Reinhart Koselleck (1923–2006), historian

- Michael Kretschmer (born 1975), politician (CDU)

- Lars Kaufmann (born 1982), handball player

- Oskar Morgenstern (1902–1977), economist

- Gustavus Adolphus Neumann (1807–1886), publisher

- Arthur Pohl (1900–1970), set designer, director and screenwriter

- Pavle Jurišić Šturm (1848–1922), Serbian Army general, born in Görlitz

- Alfred Wagenknecht (1881–1956), American Marxist politician

- Giorgio Zur (1930–2019), Catholic Archbishop and Apostolic Nuncio in Austria

Gallery

St. Peter and Paul church, the Woad House and the river Lusatian Neisse in Görlitz

St. Peter and Paul church, the Woad House and the river Lusatian Neisse in Görlitz Interior of St. Peter and Paul with its Sonnenorgel (sun organ)

Interior of St. Peter and Paul with its Sonnenorgel (sun organ) The Schönhof, the oldest Renaissance building in Görlitz

The Schönhof, the oldest Renaissance building in Görlitz Interior of the Görlitzer Warenhaus department store

Interior of the Görlitzer Warenhaus department store View over Upper Market Square taken from Reichenbach Tower, residential buildings of Zgorzelec in the background

View over Upper Market Square taken from Reichenbach Tower, residential buildings of Zgorzelec in the background Old town hall on the Lower Market Square

Old town hall on the Lower Market Square Royal coats of arms of Hungarian King Matthias Corvinus (Old Town Hall)

Royal coats of arms of Hungarian King Matthias Corvinus (Old Town Hall) Reichenbach Tower

Reichenbach Tower Courthouse

Courthouse The Landeskrone, literally "land's crown", the local mountain of Görlitz

The Landeskrone, literally "land's crown", the local mountain of Görlitz Theatre

Theatre Gothic Holy Trinity church

Gothic Holy Trinity church Thick Tower

Thick Tower Nikolai Cemetery

Nikolai Cemetery Nikolai Tower

Nikolai Tower St. Peter and Paul

St. Peter and Paul Old town hall

Old town hall Wilhelmsplatz

Wilhelmsplatz

See also

- Ludwigsdorf

- Pließnitz

References

- Wahlergebnisse 2019, Freistaat Sachsen, accessed 10 July 2021.

- "Bevölkerung des Freistaates Sachsen nach Gemeinden am 31. Dezember 2020". Statistisches Landesamt des Freistaates Sachsen (in German). June 2021.

- G. Kießling (1883), Blicke in die Mundart der südlichen Oberlausitz: Revidierter Abdruck aus dem 4. Jahresberichte des Königl. Seminars zu Löbau (in German), Zschopau: Raschkem

- Hans Klecker. "Hochzeit & Trauung | Hochzeit in Europa". Archived from the original on 22 December 2010. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- Heinz, Marlis (30 November 2015). "Hier dreht sich alles um das Drehen". morgenpost.de. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- Bena, Waldemar (2006). Szlakiem grodzisk słowiańskich i średniowiecznych zamków (in Polish and German). Zgorzelec. pp. 9–10.

- "Plemiona polskie". Encyklopedia Internautica (in Polish). Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- "Deutschlands Städte, Gemeinden und Kreise online - FindCity". findcity.de. Archived from the original on 20 May 2007. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- "Placenames of the World" by Adrian Room, McFarland Pub. 2003 page 140

- "Heinrich I., Herzog von Schlesien". Deutsche-Biographie.de (in German). Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- Köhler, Gustav (1846). Der Bund der Sechsstädte in der Ober-Lausitz: Eine Jubelschrift (in German). Görlitz: G. Heinze & Comp. p. 30.

- "Adasse (fl. 1348)." In Dictionary of Women Worldwide: 25,000 Women Through the Ages, edited by Anne Commire and Deborah Klezmer, 11. Vol. 1. Detroit, MI: Yorkin Publications, 2007. Gale eBooks (accessed 20 July 2021).

- Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon, Band 8 (in German). Leipzig. 1907. pp. 138–139.

- "Informacja historyczna". Dresden-Warszawa (in Polish). Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- "Als Tausende Griechen in Görlitz Zuflucht suchten". LR Online (in German). 8 October 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- "Eine schlichte Tafel erinnert an das unermessliche Leid im KZ Leschwitz". saechsische.de (in German). Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- "Straßensperrung". Görlitzer Anzeiger (in German). Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- "Brücke in Hagenwerder wird komplett erneuert". Görlitzer Anzeiger (in German). Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- "Jugendstil ohne Juden". juedische-allgemeine.de (in German). November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- Toby Alexrod. "In a German city with 30 Jews, a restored Art Deco synagogue will house interfaith efforts". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- "Stadt un Landkreis Görlitz". Verwaltungsgeschichte.de. Archived from the original on 3 September 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- "Gefängnis Görlitz". Bundesarchiv.de (in German). Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- "Subcamps of KL Gross- Rosen". Gross-Rosen Museum in Rogoźnica. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- Lusek, Joanna; Goetze, Albrecht (2011). "Stalag VIII A Görlitz. Historia – teraźniejszość – przyszłość". Łambinowicki rocznik muzealny (in Polish). Opole. 34: 42–43.

- Wrzyszcz, Andrzej (2008). "Z badań nad ewakuacją organów resortu sprawiedliwości Generalnego Gubernatorstwa w latach 1944–1945". Studia z dziejów państwa i prawa polskiego (in Polish). Kraków. XI: 270.

- Rejestr faktów represji na obywatelach polskich za pomoc ludności żydowskiej w okresie II wojny światowej (in Polish). Warszawa: IPN. 2014. pp. 68–69, 78, 81.

- Wojskowy Instytut Geograficzny (1925). "Görlitz (Zgorzelice)" (Map). Mapa Operacyjna Polski. 1:300,000 (in Polish).

- Wojskowy Instytut Geograficzny (1935). "Zgorzelec (Görlitz)" (Map). Mapa Operacyjna Polski. 1:300,000 (in Polish).

- "Warum Görlitz für ältere Menschen so attraktiv ist". goerlitzer-anzeiger.de. Görlitzer Anzeiger. 10 June 2019. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- "Görlitz' Generous Donor". dw.com. Deutsche Welle. 23 April 2013. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- Herbers, Klaus; Bauer, Dieter R. (2003). Der Jakobuskult in Ostmitteleuropa: Austausch - Einflüsse - Wirkungen (in German). Gunter Narr Verlag. p. 279. ISBN 978-3-8233-4012-6.

- "German Research Project Offers One Week of Free Living | DW | 14.09.2008". DW.COM a. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "Nonpareil - sweet treat from Görlitz". dw.com. Deutsche Welle. 28 April 2016. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- Die Stadt Görlitz und ihre Stadt- und Ortsteile, Stadt Görlitz, accessed 12 October 2021.

- Gebietsfläche in qkm - Stichtag 31.12. - regionale Tiefe: Gemeinden, Statistische Ämter des Bundes und der Länder

- "Willkommen" (in German). Verkehrsgesellschaft Görlitz GmbH. Archived from the original on 8 January 2019. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- "Informacje bieżące" [Current Information] (in Polish). Polnische Verkehrsgesellschaft (Polish Transport Company). Archived from the original on 10 March 2012. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- "Gorlitz, Germany Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- "Görlitz (10499) - WMO Weather Station". NOAA. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- Duke, Alan (11 August 2009). "'Basterds' pro-Nazi short made by a Jewish director - CNN.com". CNN. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- "'Newcomer Görlitz', das Stadtportrait für das MYSELF Magazin - Fotos Christian KERBER c/o SOLAR UND FOTOGRAFEN". Gosee (in German). 22 April 2016. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- "Wes Anderson's new movie has a distributor, plot". The A.V. Club. 28 March 2013. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- "Städtepartnerschaften". goerlitz.de (in German). Görlitz. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- "Tag der Deutschen Einheit". zipfelbund.de (in German). Retrieved 30 April 2020.

External links

Görlitz travel guide from Wikivoyage

Görlitz travel guide from Wikivoyage- Official website (in English)

- Official website

(in German)

(in German) - DW-World 'trial living' report.

- "Görlitz/Zgorzelec – Urban development from 12th to 21st century" on YouTube