Gandhara

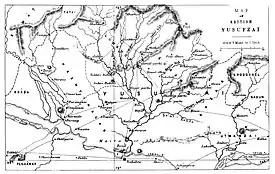

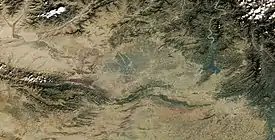

Gandhāra is the name of an ancient region located in present-day north-west Pakistan and parts of south-east Afghanistan.[1][2][3] The region centered around the Peshawar Valley and Swat river valley, though the cultural influence of "Greater Gandhara" extended across the Indus river to the Taxila region in Potohar Plateau and westwards into the Kabul Valley in Afghanistan, and northwards up to the Karakoram range.[4][5][6]

Gandhāra गन्धार (Sanskrit) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 800 BCE–c. 500 CE | |||||||||

Gandhara Location of Gandhara in South Asia (Afghanistan and Pakistan) | |||||||||

Approximate geographical region of Gandhara centered on the Peshawar Basin, in present-day northwest Pakistan. | |||||||||

| Capital | Puṣkalavati (Charsadda) Puruṣapura (Peshawer) Takshashila (Taxila) Udabhandapura (Hund) | ||||||||

| Historical era | Ancient Era | ||||||||

• Established | c. 800 BCE | ||||||||

• Disestablished | c. 500 CE | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Afghanistan Pakistan | ||||||||

Famed for its unique Gandharan style of art which is heavily influenced by the classical Greek and Hellenistic styles, Gandhara attained its height from the 1st century to the 5th century CE under the Kushan Empire, who had their capital at Peshawar (Puruṣapura). Gandhara "flourished at the crossroads of India, Central Asia, and the Middle East," connecting trade routes and absorbing cultural influences from diverse civilizations; Buddhism thrived until the 8th or 9th centuries, when Islam first began to gain sway in the region.[7] It was also the centre of Vedic and later forms of Hinduism.[8]

Gandhara's existence is attested since the time of the Rigveda (c. 1500 – c. 1200 BCE),[9][10] as well as the Zoroastrian Avesta, which mentions it as Vaēkərəta, the sixth most beautiful place on earth created by Ahura Mazda. Gandhara was conquered by the Persian Achaemenid Empire in the 6th century BCE, Alexander the Great in 327 BCE, and later became part of the Maurya Empire before being a centre of the Indo-Greek Kingdom. The region was a major centre for Greco-Buddhism under the Indo-Greeks and Gandharan Buddhism under later dynasties. Gandhara was also a central location for the spread of Buddhism to Central Asia and East Asia.[11]

The region steadily declined after the violent invasion by Alchon Huns in 6th century, and the name Gandhara disappeared after Mahmud Ghaznavi's conquest in 1001 CE.[12]

Terminology

Gandhara was known in Sanskrit as Gandhāra (गन्धार), in Avestan as Vaēkərəta, in Old Persian as Gadāra (Old Persian cuneiform: 𐎥𐎭𐎠𐎼, Gadāra, also transliterated as Gandāra since the nasal "n" before consonants was omitted in the Old Persian script, and simplified as Gandara),[13] in Akkadian and Elamite as Paruparaesanna (Para-upari-sena),[14] in Chinese as T: 犍陀羅/S: 犍陀罗 (Qiántuóluó), and in Greek as Γανδάρα (Gandhara).[15]

Etymology

One proposed origin of the name is from the Sanskrit word गन्ध gandha, meaning "perfume" and "referring to the spices and aromatic herbs which they (the inhabitants) traded and with which they anointed themselves.".[16][17] The Gandhari people are a tribe mentioned in the Rigveda, the Atharvaveda, and later Vedic texts.[18] They are recorded in the Avestan language of Zoroastrianism under the name Vaēkərəta. The name Gandhāra occurs later in the classical Sanskrit of the epics.

A Persian form of the name, Gandara, mentioned in the Behistun inscription of Emperor Darius I,[19][20] was translated as Paruparaesanna (Para-upari-sena, meaning "beyond the Hindu Kush") in Babylonian and Elamite in the same inscription.[14]

Kandahar is sometimes etymologically associated with Gandhara. However, Kandahar was not part of the territory of Gandhara.[21] It is instead etymologically related to "Alexandria".[22]

Geography

The boundaries of Gandhara varied throughout history. Sometimes the Peshawar Valley and Taxila were collectively referred to as Gandhara; sometimes the Kabul Valley and Swat (Sanskrit: Suvāstu) were included.[23] The kingdom was ruled from capitals at Kapisi (Bagram),[24] Pushkalavati (Charsadda), Taxila, Puruṣapura (Peshawar) and in its final days from Udabhandapura (Hund) on the River Indus.

Early History

Stone age

Evidence of the Stone Age human inhabitants of Gandhara, including stone tools and burnt bones, was discovered at Sanghao near Mardan in area caves. The artefacts are approximately 15,000 years old. More recent excavations point to 30,000 years before the present.

Gandhara grave culture

Gandhara’s first recorded civilization was the Grave Culture that emerged c. 1400 BCE and lasted until 800 BCE,[25] and named for their distinct funerary practices. It was found along the Middle Swat River course, even though earlier research considered it to be expanded to the Valleys of Dir, Kunar, Chitral, and Peshawar.[26] It has been regarded as a token of the Indo-Aryan migrations, but has also been explained by local cultural continuity. Backwards projections, based on ancient DNA analyses, suggest ancestors of Swat culture people mixed with a population coming from Inner Asia Mountain Corridor, which carried Steppe ancestry, sometime between 1900 and 1500 BCE.[27]

.png.webp)

.png.webp)

Vedic Gandhāris and the Gandhāra Kingdom

The first mention of the Gandhārīs is attested once in the Ṛgveda as a tribe that has sheep with good wool. In the Atharvaveda, the Gandhārīs are mentioned alongside the Mūjavants, the Āṅgeyas. and the Māgadhīs in a hymn asking fever to leave the body of the sick man and instead go those aforementioned tribes. The tribes listed were the furthermost border tribes known to those in Madhyadeśa, the Āṅgeyas and Māgadhīs in the east, and the Mūjavants and Gandhārīs in the north.[28][29]

.png.webp)

The Gāndhārī king Nagnajit and his son Svarajit are mentioned in the Brāhmaṇas, according to which they received Brahmanic consecration, but their family's attitude towards ritual is mentioned negatively,[30] with the royal family of Gandhāra during this period following non-Brahmanical religious traditions. According to the Jain Uttarādhyayana-sūtra, Nagnajit, or Naggaji, was a prominent king who had adopted Jainism and was comparable to Dvimukha of Pāñcāla, Nimi of Videha, Karakaṇḍu of Kaliṅga, and Bhīma of Vidarbha; Buddhist sources instead claim that he had achieved paccekabuddhayāna.[31][32][33]

By the later Vedic period, the situation had changed, and the Gāndhārī capital of Takṣaśila had become an important centre of knowledge where the men of Madhya-desa went to learn the three Vedas and the eighteen branches of knowledge, with the Kauśītaki Brāhmaṇa recording that brāhmaṇas went north to study. According to the Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa and the Uddālaka Jātaka, the famous Vedic philosopher Uddālaka Āruṇi was among the famous students of Takṣaśila, and the Setaketu Jātaka claims that his son Śvetaketu also studied there. In the Chāndogya Upaniṣad, Uddālaka Āruṇi himself favourably referred to Gāndhārī education to the Vaideha king Janaka.[30]

During the 6th century BCE, Gandhāra was an important imperial power in north-west Iron Age South Asia, with the valley of Kaśmīra being part of the kingdom,[31] while the other states of the Punjab region, such as the Kekayas, Madrakas, Uśīnaras, and Shivis being under Gāndhārī suzerainty. The Gāndhārī king Pukkusāti, who reigned around 550 BCE, engaged in expansionist ventures which brought him into conflict with the king Pradyota of the rising power of Avanti. Pukkusāti was successful in this struggle with Pradyota, but war broke out between him and the Pāṇḍava tribe located in the Punjab region, and who were threatened by his expansionist policy.[32][34] Pukkusāti also engaged in friendly relations with the king Bimbisāra of Magadha.[32]

Due to this important position, Buddhist texts listed the Gandhāra kingdom as one of the sixteen Mahājanapadas ("great realms") of Iron Age South Asia.[35][36]

Achaemenid Gandhara

By the later 6th century BCE, the founder of the Persian Achaemenid Empire, Cyrus, soon after his conquests of Media, Lydia, and Babylonia, marched into Gandhara and annexed it into his empire.[42] The scholar Kaikhosru Danjibuoy Sethna advanced that Cyrus had conquered only the trans-Indus borderlands around Peshawar which had belonged to Gandhāra while Pukkusāti remained a powerful king who maintained his rule over the rest of Gandhāra and the western Punjab.[43]

However, according to the scholar Buddha Prakash, Pukkusāti might have acted as a bulwark against the expansion of the Persian Achaemenid Empire into north-west South Asia. This hypothesis posits that the army which Nearchus claimed Cyrus had lost in Gedrosia had in fact been defeated by Pukkusāti's Gāndhārī kingdom. Therefore, following Prakash's position, the Achaemenids would have been able to conquer Gandhāra only after a period of decline of Gandhāra after the reign of Pukkusāti combined the growth of Achaemenid power under the kings Cambyses II and Darius I.[32] However, the presence of Gandhāra, referred to as Gandāra in Old Persian, among the list of Achaemenid provinces in Darius's Behistun Inscription confirms that his empire had inherited this region from conquests carried out earlier by Cyrus.[42]

It is unknown whether Pukkusāti remained in power after the Achaemenid conquest as a Persian vassal or if he was replaced by a Persian satrap (governor),[44] although Buddhist sources claim that he renounced his throne and became a monk after becoming a disciple of the Buddha.[45] The annexation under Cyrus was limited to Gandhāra proper, after which the peoples of the Punjab region previously under Gāndhārī authority took advantage of the new power vacuum to form their own states.[32]

Under Persian rule, a system of centralized administration, with a bureaucratic system, was introduced into the Indus Valley for the first time. Provinces or "satrapy" were established with provincial capitals.

Gandhara satrapy, established 518 BCE with its capital at Pushkalavati (Charsadda).[46]

The inscription on Darius' (521–486 BCE) tomb at Naqsh-i-Rustam near Persepolis records Gadāra (Gandāra) along with Hindush (Hənduš, Sindh) in the list of satrapies. By about 380 BC the Persian hold on the region had weakened. Many small kingdoms sprang up in Gandhara.

Macedonian Gandhara

In 327 BCE, Alexander the Great conquered Gandhara as well as the Indian satrapies of the Persian Empire. The expeditions of Alexander were recorded by his court historians and by Arrian (around 175 CE) in his Anabasis Alexandri and by other chroniclers many centuries after the event.

In the winter of 327 BCE, Alexander invited all the chieftains in the remaining five Achaemenid satraps to submit to his authority. Ambhi, then ruler of Taxila in the former Hindush satrapy complied, but the remaining tribes and clans in the former satraps of Gandhara, Arachosia, Sattagydia and Gedrosia rejected Alexander's offer.

The first tribe they encountered were the Aspasioi tribe of the Kunar Valley, who initiated a fierce battle against Alexander, in which he himself was wounded in the shoulder by a dart. However, the Aspasioi eventually lost and 40,000 people were enslaved. Alexander then continued in a southwestern direction where he encountered the Assakenoi tribe of the Swat & Buner valleys in April 326 BCE. The Assakenoi fought bravely and offered stubborn resistance to Alexander and his army in the cities of Ora, Bazira (Barikot) and Massaga. So enraged was Alexander about the resistance put up by the Assakenoi that he killed the entire population of Massaga and reduced its buildings to rubble. A similar slaughter then followed at Ora,[47] another stronghold of the Assakenoi. The stories of these slaughters reached numerous Assakenians, who began fleeing to Aornos, a hill-fort located between Shangla and Kohistan. Alexander followed close behind their heels and besieged the strategic hill-fort, eventually capturing and destroying the fort and killing everyone inside. The remaining smaller tribes either surrendered or like the Astanenoi tribe of Pushkalavati (Charsadda) were quickly neutralized where 38,000 soldiers and 230,000 oxen were captured by Alexander.[48] Eventually Alexander's smaller force would meet with the larger force which had come through the Khyber Pass met at Attock. With the conquest of Gandhara complete, Alexander switched to strengthening his military supply line, which by now stretched dangerously vulnerable over the Hindu Kush back to Balkh in Bactria.

After conquering Gandhara and solidifying his supply line back to Bactria, Alexander combined his forces with the King Ambhi of Taxila and crossed the River Indus in July 326 BCE to begin the Archosia (Punjab) campaign. Alexander nominated officers as Satraps of the new provinces, and in Gandhara, Oxyartes was nominated to the position of Satrap in 326 BCE.

Mauryan Gandhara

.jpg.webp)

After a battle with Seleucus Nicator (Alexander's successor in Asia) in 305 BCE, the Mauryan Emperor extended his domain up to and including present Southern Afghanistan. With the completion of the Empire's Grand Trunk Road, the region prospered as a centre of trade. Gandhara remained a part of the Mauryan Empire for about a century and a half.

Ashoka, the grandson of Chandragupta, was one of the greatest Indian rulers. Like his grandfather, Ashoka also started his career in Gandhara as a governor. Later he became a Buddhist and promoted Buddhism. He built many stupas in Gandhara. Mauryan control over the northwestern frontier, including the Yonas, Kambojas, and the Gandharas, is attested from the Rock Edicts left by Ashoka.

According to one school of scholars, the Gandharas and Kambojas were cognate people.[49][50][51] It is also contended that the Kurus, Kambojas, Gandharas and Bahlikas were cognate people and all had Iranian affinities,[52] or that the Gandhara and Kamboja were nothing but two provinces of one empire and hence influencing each other's language.[53] However, the local language of Gandhara is represented by Panini's conservative bhāṣā ("language"), which is entirely different from the Iranian (Late Avestan) language of the Kamboja that is indicated by Patanjali's quote of Kambojan śavati 'to go' (= Late Avestan šava(i)ti).[note 1]

Ancient Era

Indo-Greek Kingdom

.jpeg.webp)

The decline of the Mauryan Empire left Gandhara open to Greco-Bactrian invasions. Present-day southern Afghanistan was absorbed by Demetrius I of Bactria in 180 BCE. Around about 185 BCE, Demetrius moved into Indian subcontinent; he invaded and conquered Gandhara and the Punjab. Later, wars between different groups of Bactrian Greeks resulted in the independence of Gandhara from Bactria and the formation of the Indo-Greek kingdom. Menander I was its most famous king. He ruled from Taxila and later from Sagala (Sialkot). He rebuilt Taxila (Sirkap) and Pushkalavati. He became a Buddhist and is remembered in Buddhist records for his discussions with the great Buddhist philosopher, Nāgasena, in the book Milinda Panha.

Around the time of Menander's death in 140 BCE, the Central Asian Kushans overran Bactria and ended Greek rule there.

Indo-Scythian Kingdom

Around 80 BCE, the Sakas, diverted by their Parthian cousins from Iran, moved into Gandhara and other parts of Pakistan and Western India. The most famous king of the Sakas, Maues, established himself in Gandhara.

Indo-Parthian Kingdom

By 90 BCE the Parthians had taken control of eastern Iran and, around 50 BCE, they put an end to the last remnants of Greek rule in today's Afghanistan. Eventually an Indo-Parthian dynasty succeeded in taking control of Gandhara. The Parthians continued to support Greek artistic traditions. The start of the Gandharan Greco-Buddhist art is dated to about 75–50 BCE. Links between Rome and the Indo-Parthian kingdoms existed.[54] There is archaeological evidence that building techniques were transmitted between the two realms. Christian records claim that around 40 CE Thomas the Apostle visited the Indian subcontinent and encountered the Indo-Parthian king Gondophares.[55]

Kushan Gandhara

The Parthian dynasty fell in about 75 to another group from Central Asia. The Kushans, known as Yuezhi in the Chinese source Hou Han Shu (argued by some to be ethnically Asii) moved from Central Asia to Bactria, where they stayed for a century. Around 75 CE, one of their tribes, the Kushan (Kuṣāṇa), under the leadership of Kujula Kadphises gained control of Gandhara. The Kushan empire began as a Central Asian kingdom, and expanded into Afghanistan and northwestern India in the early centuries CE.[56]

The Kushan period is considered the Golden Period of Gandhara. Peshawar Valley and Taxila are littered with ruins of stupas and monasteries of this period. Gandharan art flourished and produced some of the best pieces of sculpture from the Indian subcontinent. Many monuments were created to commemorate the Jatakas.

Gandhara's culture peaked during the reign of the great Kushan king Kanishka the Great (127 CE – 150 CE). The cities of Taxila (Takṣaśilā) at Sirsukh and Purushapura (modern day Peshawar) reached new heights. Purushapura along with Mathura became the capital of the great empire stretching from Central Asia to Northern India with Gandhara being in the midst of it. Emperor Kanishka was a great patron of the Buddhist faith; Buddhism spread from India to Central Asia and the Far East across Bactria and Sogdia, where his empire met the Han Empire of China. Buddhist art spread from Gandhara to other parts of Asia. Under Kanishka, Gandhara became a holy land of Buddhism and attracted Chinese pilgrims eager to view the monuments associated with many Jatakas.

In Gandhara, Mahayana Buddhism flourished and Buddha was represented in human form. Under the Kushans new Buddhists stupas were built and old ones were enlarged. Huge statues of the Buddha were erected in monasteries and carved into the hillsides. Kanishka also built a great 400-foot tower at Peshawar. This tower was reported by Chinese monks Faxian, Song Yun, and Xuanzang who visited the country. This structure was destroyed and rebuilt many times until it was finally destroyed by Mahmud of Ghazni in the 11th century.

Kidarites

The Kidarites conquered Peshawar and parts of northwest Indian subcontinent including Gandhara probably sometime between 390 and 410 from Kushan empire,[57] around the end of the rule of Gupta Emperor Chandragupta II or beginning of the rule of Kumaragupta I.[58] It is probably the rise of the Hephthalites and the defeats against the Sasanians which pushed the Kidarites into northern India. Their last ruler in Gandhara was Kandik, around 500 CE.

Alchon Huns

The Alchon invasion of the Indian subcontinent eradicated the Kidarite Huns who had preceded them by about a century, and contributed to the fall of the Gupta Empire, in a sense bringing an end to Classical India.[59][60]

Hephthalite Empire

The Hūṇas (as they were known in India) were initially based in the Oxus basin in Central Asia and established their control over Gandhara in the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent by about 465 CE.[61] From there, they fanned out into various parts of northern, western, and central India. The Hūṇas are mentioned in several ancient texts such as the Rāmāyaṇa, Mahābhārata, Purāṇas, and Kalidasa's Raghuvaṃśa.[62]

Numerous incidents of violence were reported during this period. The Dharmarajika Stupa at Takṣaśilā has evidence of a massacre there by the Huns.[63] Mihirakula is said to have become a "terrible persecutor" of Buddhism which may have contributed to decline of Buddhism in the Gandhara region.[64] Xuanzang tells us that initially Mihirakula was interested in learning about Buddhism, and asked the monks to send him a teacher; the monks insulted him by recommending a servant of his own household for the purpose. This incident is said to have turned Mihirakula virulently anti-Buddhist, although some have suggested the anti-Buddhist reputation was exaggerated.[65] It is possible that Mihirakula, who may have been inclined toward Shaivism (although his coins also have representations of other deities such as the goddess Lakshmi), was inimical toward both Buddhists and Jainas.[65]

The travel records of many Chinese Buddhist pilgrims record that Gandhara was going through a transformation during these centuries. Buddhism was declining, and Hinduism was rising. Faxian traveled around 400, when Prakrit was the language of the people, and Buddhism was flourishing. 100 years later, when Song Yun visited in 520, a different situation was described: the area had been destroyed by the White Huns and was ruled by Lae-Lih, who did not practice the laws of the Buddha. Xuanzang visited India around 644 CE and found Buddhism on the wane in Gandhara and Hinduism in the ascendant. Gandhara was ruled by a king from Kabul, who respected Buddha's law, but Taxila was in ruins, and Buddhist monasteries were deserted.

Later History

Kabul Shahi

After the fall of the Sassanid Empire to the Arabs in 651 CE, the region south of the Hindukush along with Gandhara came under pressure from Muslims. After failure of multiple campaigns by Arabs they failed to extend their rule to Gandhara.

Gandhara was ruled from Kabul by the Kabul Shahi for next 200 years. Sometime in the 9th century the Kabul Shahi were replaced by the Hindu Shahi.

Hindu Shahi and Decline

Based on various records it is estimated that Hindu Shahi was formed in 850 CE. According to Al-Biruni (973–1048), Kallar, a Brahmin minister, founded the Hindu Shahi dynasty around 843 CE. The dynasty ruled from Kabul, later moved their capital to Udabhandapura. They built great temples all over their kingdoms. Some of these buildings are still in good condition in the Salt Range of the Punjab.

Jayapala was the last great king of the Hindu Shahi dynasty. His empire extended from west of Kabul to the river Sutlej. However, this expansion of Gandhara kingdom coincided with the rise of the powerful Ghaznavid Empire under Sabuktigin. Defeated twice by Sabuktigin and then by Mahmud of Ghazni in the Kabul valley, Jayapala gave his life on a funeral pyre. Anandapala, a son of Jayapala, moved his capital near Nandana in the Salt Range. In 1021 the last king of this dynasty, Trilochanapala, was assassinated by his own troops which spelled the end of Gandhara. Subsequently, some Shahi princes moved to Kashmir and became active in local politics.

The city of Kandahar in Afghanistan is said to have been named after Gandhara. According to H.W. Bellow, an emigrant from the collapsing Gandhara region in the 5th century brought this name to modern Kandahar.

Writing in c. 1030, Al Biruni reported on the devastation caused during the conquest of Gandhara and much of north-west India by Mahmud of Ghazni following his defeat of Jayapala in the Battle of Peshawar at Peshawar in 1001:

Now in the following times no Muslim conqueror passed beyond the frontier of Kâbul and the river Sindh until the days of the Turks, when they seized the power in Ghazna under the Sâmânî dynasty, and the supreme power fell to the lot of Nâṣir-addaula Sabuktagin. This prince chose the holy war as his calling, and therefore called himself al-Ghâzî ("the warrior/invader"). In the interest of his successors he constructed, in order to weaken the Indian frontier, those roads on which afterwards his son Yamin-addaula Maḥmûd marched into India during a period of thirty years and more. God be merciful to both father and son ! Maḥmûd utterly ruined the prosperity of the country, and performed there wonderful exploits, by which the Hindus became like atoms of dust scattered in all directions, and like a tale of old in the mouth of the people. Their scattered remains cherish, of course, the most inveterate aversion towards all Muslims. This is the reason, too, why Hindu sciences have retired far away from those parts of the country conquered by us, and have fled to places which our hand cannot yet reach, to Kashmir, Benares, and other places. And there the antagonism between them and all foreigners receives more and more nourishment both from political and religious sources.[66]

During the closing years of the tenth and the early years of the succeeding century of our era, Mahmud the first Sultan and Musalman of the Turk dynasty of kings who ruled at Ghazni, made a succession of inroads twelve or fourteen in number, into Gandhar – the present Peshawar valley – in the course of his proselytizing invasions of Hindustan.[67]

Fire and sword, havoc and destruction, marked his course everywhere. Gandhar which was styled the Garden of the North was left at his death a weird and desolate waste. Its rich fields and fruitful gardens, together with the canal which watered them (the course of which is still partially traceable in the western part of the plain), had all disappeared. Its numerous stone built cities, monasteries, and topes with their valuable and revered monuments and sculptures, were sacked, fired, razed to the ground, and utterly destroyed as habitations.[67]

Rediscovery

By the time Gandhara had been absorbed into the empire of Mahmud of Ghazni, Buddhist buildings were already in ruins and Gandhara art had been forgotten. After Al-Biruni, the Kashmiri writer Kalhaṇa wrote his book Rajatarangini in 1151. He recorded some events that took place in Gandhara, and provided details about its last royal dynasty and capital Udabhandapura.

In the 19th century, British soldiers and administrators started taking an interest in the ancient history of the Indian Subcontinent. In the 1830s coins of the post-Ashoka period were discovered, and in the same period Chinese travelogues were translated. Charles Masson, James Prinsep, and Alexander Cunningham deciphered the Kharosthi script in 1838. Chinese records provided locations and site plans for Buddhist shrines. Along with the discovery of coins, these records provided clues necessary to piece together the history of Gandhara. In 1848 Cunningham found Gandhara sculptures north of Peshawar. He also identified the site of Taxila in the 1860s. From then on a large number of Buddhist statues were discovered in the Peshawar valley.

Archaeologist John Marshall excavated at Taxila between 1912 and 1934. He discovered separate Greek, Parthian, and Kushan cities and a large number of stupas and monasteries. These discoveries helped to piece together much more of the chronology of the history of Gandhara and its art.

After 1947 Ahmed Hassan Dani and the Archaeology Department at the University of Peshawar made a number of discoveries in the Peshawar and Swat Valley. Excavation of many of the sites of Gandhara Civilization are being done by researchers from Peshawar and several universities around the world.

Language

Gandhara's language was a Prakrit or "Middle Indo-Aryan" dialect, usually called Gāndhārī.[68] Hindko from Peshawar, which was the capital of Gandhara, came from Shuraseni prakrit a language spoken in Gandhara.[69][70][71] Under the Kushan Empire, Gāndhārī spread into adjoining regions of South and Central Asia.[68] It used the Kharosthi script, which is derived from the Aramaic script, and it died out about in the 4th century CE.[68][72]

Linguistic evidence links some groups of the Dardic languages with Gandhari.[73][74][75] The Kohistani languages, now all being displaced from their original homelands, were once more widespread in the region and most likely descend from the ancient dialects of the region of Gandhara.[76][77] The last to disappear was Tirahi, still spoken some years ago in a few villages in the vicinity of Jalalabad in eastern Afghanistan, by descendants of migrants expelled from Tirah by the Afridi Pashtuns in the 19th century.[78] Georg Morgenstierne claimed that Tirahi is "probably the remnant of a dialect group extending from Tirah through the Peshawar district into Swat and Dir".[79] Nowadays, it must be entirely extinct and the region is now dominated by Iranian languages brought in by later migrants, such as Pashto.[78] Among the modern day Indo-Aryan languages still spoken today, Torwali shows the closest linguistic affinity possible to Niya, a dialect of Gāndhārī.[77][80]

Religion

Buddhism

Mahāyāna Buddhism

Mahāyāna Pure Land sutras were brought from the Gandhāra region to China as early as 147 CE, when the Kushan monk Lokakṣema began translating some of the first Buddhist sutras into Chinese.[81] The earliest of these translations show evidence of having been translated from the Gāndhārī language.[82] Lokakṣema translated important Mahāyāna sūtras such as the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra, as well as rare, early Mahāyāna sūtras on topics such as samādhi, and meditation on the Buddha Akṣobhya. Lokaksema's translations continue to provide insight into the early period of Mahāyāna Buddhism. This corpus of texts often includes and emphasizes ascetic practices and forest dwelling, and absorption in states of meditative concentration:[83]

Paul Harrison has worked on some of the texts that are arguably the earliest versions we have of the Mahāyāna sūtras, those translated into Chinese in the last half of the second century AD by the Indo-Scythian translator Lokakṣema. Harrison points to the enthusiasm in the Lokakṣema sūtra corpus for the extra ascetic practices, for dwelling in the forest, and above all for states of meditative absorption (samādhi). Meditation and meditative states seem to have occupied a central place in early Mahāyāna, certainly because of their spiritual efficacy but also because they may have given access to fresh revelations and inspiration.

Some scholars believe that the Mahāyāna Longer Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra was compiled in the age of the Kushan Empire in the 1st and 2nd centuries CE, by an order of Mahīśāsaka bhikṣus which flourished in the Gandhāra region.[84][85] However, it is likely that the longer Sukhāvatīvyūha owes greatly to the Mahāsāṃghika-Lokottaravāda sect as well for its compilation, and in this sutra there are many elements in common with the Lokottaravādin Mahāvastu.[84] There are also images of Amitābha Buddha with the bodhisattvas Avalokiteśvara and Mahāsthāmaprāpta which were made in Gandhāra during the Kushan era.[86]

The Mañjuśrīmūlakalpa records that Kaniṣka of the Kushan Empire presided over the establishment of the Mahāyāna Prajñāpāramitā teachings in the northwest.[87] Tāranātha wrote that in this region, 500 bodhisattvas attended the council at Jālandhra monastery during the time of Kaniṣka, suggesting some institutional strength for Mahāyāna in the north-west during this period.[87] Edward Conze goes further to say that Prajñāpāramitā had great success in the north-west during the Kushan period, and may have been the "fortress and hearth" of early Mahāyāna, but not its origin, which he associates with the Mahāsāṃghika branch of Buddhism.[88]

Destruction of Buddhist relics by Taliban

Swat Valley in Pakistan has many Buddhist carvings, and stupas, and Jehanabad contains a Seated Buddha statue.[89] Kushan era Buddhist stupas and statues in Swat valley were demolished after two attempts by the Taliban and the Jehanabad Buddha's face was dynamited.[90][91][92] Only the Buddhas of Bamiyan were larger than the carved giant Buddha statues in Swat near Manglore which the Taliban attacked.[93] The government did nothing to safeguard the statue after the initial attempts to destroy the Buddha, which did not cause permanent harm. But when a second attack took place on the statue, the feet, shoulders, and face were demolished.[94] Taliban and looters destroyed many of Pakistan's Buddhist artefacts from the Buddhist Gandhara civilization especially in the Swat Valley.[95]

Buddhist translators

Gandharan Buddhist missionaries were active, with other monks from Central Asia, from the 2nd century CE in the Han-dynasty (202 BC – 220 CE) at China's capital of Luoyang, and particularly distinguished themselves by their translation work. They promoted scriptures from Early Buddhist schools as well as those from the Mahāyāna. These translators included:

- Lokakṣema, a Kushan and the first to translate Mahāyāna scriptures into Chinese (167–186)

- Zhi Yao (fl. 185), a Kushan monk, second generation of translators after Lokakṣema

- Zhi Qian (220–252), a Kushan monk whose grandfather had settled in China during 168–190

- Zhi Yue (fl. 230), a Kushan monk who worked at Nanjing

- Dharmarakṣa (265–313), a Kushan whose family had lived for generations at Dunhuang

- Jñānagupta (561–592), a monk and translator from Gandhāra

- Śikṣānanda (652–710), a monk and translator from Oḍḍiyāna, Gandhāra

- Prajñā (fl. 810), a monk and translator from Kabul, who educated the Japanese Kūkai in Sanskrit texts

Textual finds

The Chinese Buddhist monk Xuanzang visited a Lokottaravāda monastery in the 7th century, at Bamiyan, Afghanistan. The site of this monastery has since been rediscovered by archaeologists.[96] Birchbark and palm leaf manuscripts of texts in this monastery's collection, including Mahāyāna sūtras, have been discovered at the site, and these are now located in the Schøyen Collection. Some manuscripts are in the Gāndhārī language and Kharoṣṭhī script, while others are in Sanskrit and written in forms of the Gupta script. Manuscripts and fragments that have survived from this monastery's collection include the following source texts:[96]

- Pratimokṣa Vibhaṅga of the Mahāsāṃghika-Lokottaravāda (MS 2382/269)

- Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra, a sūtra from the Āgamas (MS 2179/44)

- Caṃgī Sūtra, a sūtra from the Āgamas (MS 2376)

- Vajracchedikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra, a Mahāyāna sūtra (MS 2385)

- Bhaiṣajyaguru Sūtra, a Mahāyāna sūtra (MS 2385)

- Śrīmālādevī Siṃhanāda Sūtra, a Mahāyāna sūtra (MS 2378)

- Pravāraṇa Sūtra, a Mahāyāna sūtra (MS 2378)

- Sarvadharmapravṛttinirdeśa Sūtra, a Mahāyāna sūtra (MS 2378)

- Ajātaśatrukaukṛtyavinodana Sūtra, a Mahāyāna sūtra (MS 2378)

- Śāriputrābhidharma Śāstra (MS 2375/08)

A Sanskrit manuscript of the Bhaiṣajyaguruvaiḍūryaprabhārāja Sūtra was among the textual finds at Gilgit, Pakistan, attesting to the popularity of the Medicine Buddha in Gandhāra.[97] The manuscripts in this find are dated before the 7th century, and are written in the upright Gupta script.[97]

Art

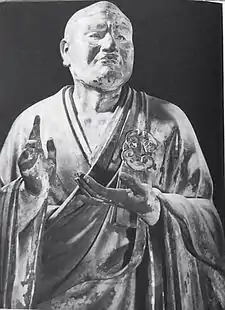

Gandhāra is noted for the distinctive Gandhāra style of Buddhist art, which shows influence of Parthian, Scythian, Roman, Graeco-Bactrian and local Indian influences from the Gangetic Valley.[98] This development began during the Parthian Period (50 BCE–75 CE). The Gandhāran style flourished and achieved its peak during the Kushan period, from the 1st to the 5th centuries. It declined and was destroyed after the invasion of the White Huns in the 5th century. Siddhartha shown as a bejeweled prince (before the Sidhartha renounces palace life) is a common motif.[99]

Stucco, as well as stone, were widely used by sculptors in Gandhara for the decoration of monastic and cult buildings.[99] Stucco provided the artist with a medium of great plasticity, enabling a high degree of expressiveness to be given to the sculpture. Sculpting in stucco was popular wherever Buddhism spread from Gandhara – Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Central Asia, and China.

Buddhist imagery combined with some artistic elements from the cultures of the Hellenistic world. An example is the youthful Buddha, his hair in wavy curls, similar to statutes of Apollo.[99]

Sacred artworks and architectural decorations used limestone for stucco composed by a mixture of local crushed rocks (i.e. schist and granite which resulted compatible with the outcrops located in the mountains northwest of Islamabad.[100]

Standing Bodhisattva (1st–2nd century)

Standing Bodhisattva (1st–2nd century) Buddha head (2nd century)

Buddha head (2nd century) Buddha head (4th–6th century)

Buddha head (4th–6th century) Buddha in acanthus capital

Buddha in acanthus capital The Greek god Atlas, supporting a Buddhist monument, Hadda

The Greek god Atlas, supporting a Buddhist monument, Hadda The Bodhisattva Maitreya (2nd century)

The Bodhisattva Maitreya (2nd century) Wine-drinking and music, Hadda (1st–2nd century)

Wine-drinking and music, Hadda (1st–2nd century) Maya's white elephant dream (2nd–3rd century)

Maya's white elephant dream (2nd–3rd century) The birth of Siddharta (2nd–3rd century)

The birth of Siddharta (2nd–3rd century) The Great Departure from the Palace (2nd–3rd century)

The Great Departure from the Palace (2nd–3rd century) The end of ascetism (2nd–3rd century)

The end of ascetism (2nd–3rd century) The Buddha preaching at the Deer Park in Sarnath (2nd–3rd century)

The Buddha preaching at the Deer Park in Sarnath (2nd–3rd century) Scene of the life of the Buddha (2nd–3rd century)

Scene of the life of the Buddha (2nd–3rd century) The death of the Buddha, or parinirvana (2nd–3rd century)

The death of the Buddha, or parinirvana (2nd–3rd century) A sculpture from Hadda, (3rd century)

A sculpture from Hadda, (3rd century) The Bodhisattva and Chandeka, Hadda (5th century)

The Bodhisattva and Chandeka, Hadda (5th century) The Buddha and Vajrapani under the guise of Herakles

The Buddha and Vajrapani under the guise of Herakles Hellenistic decorative scrolls from Hadda, Afghanistan

Hellenistic decorative scrolls from Hadda, Afghanistan Hellenistic scene, Gandhara (1st century)

Hellenistic scene, Gandhara (1st century) A stone plate (1st century).

A stone plate (1st century)..jpg.webp) "Laughing boy" from Hadda

"Laughing boy" from Hadda Bodhisattva seated in meditation

Bodhisattva seated in meditation

| History of Pakistan |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

Important Gandharans

Important people from ancient region of Gandhara are as follows;

- Pāṇini (4th century BCE), he was a Sanskrit philologist, grammarian, and a revered scholar from Gandhara. Pāṇini is known for his text Aṣṭādhyāyī, a sutra-style treatise on Sanskrit grammar.

- Chanakya (4th century BCE), he was an ancient Gandharan teacher, philosopher, economist, jurist and royal advisor. Chanakya assisted the first Mauryan emperor Chandragupta in his rise to power, and his work Arthashastra is considered Pioneer of field of political science in India.

- Garab Dorje (1st century CE), founder of Dzogchen (Great Perfection) tradition.

- Kumāralāta (3rd century), Kumāralāta was the founder of Sautrāntika school of Buddhism.

- Vasubandhu (4th century), Vasubandhu is considered one of the most influential thinkers in the Gandharan Buddhist philosophical tradition. In Jōdo Shinshū, he is considered the Second Patriarch; in Chan Buddhism, he is the 21st Patriarch. His writing Abhidharmakośakārikā ("Commentary on the Treasury of the Abhidharma") is widely used in Tibetan and East Asian Buddhism.

| Part of a series on |

| Eastern philosophy |

|---|

|

|

- Asanga (4th century), he was "one of the most important spiritual figures" of Mahayana Buddhism and the "founder of the Yogachara school". His book Mahāyānasaṃgraha (MSg) is the key work of the Yogācāra school of Mahāyāna Buddhist philosophy.

- Padmasambhāva (8th century), he is considered the Second Buddha by the Nyingma school, the oldest Buddhist school in Tibet known as "the ancient one".

Major cities

Major cities of ancient Gandhara are as follows:

Timeline

- c. 2300 – c. 1400 BCE Indus Valley civilization

- c. 1400 – c. 800 BCE Gandhara grave culture

- c. 1200 – c. 800 BCE Gandhari people mentioned in Rigveda and Atharvaveda.

- c. 800 – c. 518 BCE Gandhara Kingdom

- c. 518 – c. 326 BCE Persian Empire. Under direct Persian control and/or local control under Achaemenid suzerainty.

- c. 326 – c. 305 BCE Occupied by Alexander the Great and Macedonian generals

- c. 305 – c. 185 BCE Controlled by the Maurya dynasty, founded by Chandragupta. Converted to Buddhism under King Ashoka (273–232 BC)

- c. 185 – c. 97 BCE Under control of the Indo-Greek Kingdom, with some incursions of the Indo-Scythians from around 100 BC

- c. 97 BCE – c. 7 CE Saka (Indo-Scythian) Rule

- c. 7 – c. 75 CE Parthian invasion and Indo-Parthian Kingdom, Rule of Commander Aspavarman?.

- c. 75 – c. 230 CE Kushan Empire

- c. 230 – c. 440 CE Kushanshas under Persian Sassanid suzerainty

- c. 450 – c. 565 CE White Huns (Hephthalites)

- c. 565 – c. 644 CE Nezak kingdom, ruled from Kapisa and Udabhandapura

- c. 644 – c. 870 CE Kabul Shahi, ruled from Kabul

- c. 870 – 1021 CE Hindu Shahi, ruled from Udabhandapura

- c. 1021 – c. 1100 CE Conquered and controlled by the Ghaznavid empire

See also

- Gandhari people

- History of India

- History of Pakistan

- Kambojas

- Kashmir Smast

- Mahajanapadas

- Mankiala

Notes

- NOTE: See long discussion under mahajanapada from the Ancient Buddhist text Anguttara Nikaya's list of mahajanapadas.

References

- Kulke, Professor of Asian History Hermann; Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (2004). A History of India. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-32919-4.

- Warikoo, K. (2004). Bamiyan: Challenge to World Heritage. Third Eye. ISBN 978-81-86505-66-3.

- Hansen, Mogens Herman (2000). A Comparative Study of Thirty City-state Cultures: An Investigation. Kgl. Danske Videnskabernes Selskab. ISBN 978-87-7876-177-4.

- Neelis, Early Buddhist Transmission and Trade Networks 2010, p. 232.

- Eggermont, Alexander's Campaigns in Sind and Baluchistan 1975, pp. 175–177.

- Badian, Ernst (1987), "Alexander at Peucelaotis", The Classical Quarterly, 37 (1): 117–128, doi:10.1017/S0009838800031712, JSTOR 639350, S2CID 246878679

- Kurt A. Behrendt (2007), The Art of Gandhara in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp.4-5,91

-

- Schmidt, Karl J. (1995). An Atlas and Survey of South Asian History, p.120: "In addition to being a center of religion for Buddhists, as well as Hindus, Taxila was a thriving center for art, culture, and learning."

- Srinivasan, Doris Meth (2008). "Hindu Deities in Gandharan art," in Gandhara, The Buddhist Heritage of Pakistan: Legends, Monasteries, and Paradise, pp.130-143: "Gandhara was not cut off from the heartland of early Hinduism in the Gangetic Valley. The two regions shared cultural and political connections and trade relations and this facilitated the adoption and exchange of religious ideas. [...] It is during the Kushan Era that flowering of religious imagery occurred. [...] Gandhara often introduced its own idiosyncratic expression upon the Buddhist and Hindu imagery it had initially come in contact with."

- Blurton, T. Richard (1993). Hindu Art, Harvard University Press: "The earliest figures of Shiva which show him in purely human form come from the area of ancient Gandhara" (p.84) and "Coins from Gandhara of the first century BC show Lakshmi [...] four-armed, on a lotus." (p.176)

- "Rigveda 1.126:7, English translation by Ralph TH Griffith".

- Arthur Anthony Macdonell (1997). A History of Sanskrit Literature. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 130–. ISBN 978-81-208-0095-3.

- "UW Press: Ancient Buddhist Scrolls from Gandhara". Retrieved April 2018.

- Mohiuddin, Yasmeen Niaz (2007). Pakistan: A Global Studies Handbook. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781851098019.

- Some sounds are omitted in the writing of Old Persian, and are shown with a raised letter.Old Persian p.164Old Persian p.13. In particular Old Persian nasals such as "n" were omitted in writing before consonants Old Persian p.17Old Persian p.25

- Perfrancesco Callieri, INDIA ii. Historical Geography, Encyclopaedia Iranica, 15 December 2004.

- Herodotus Book III, 89-95

- Thomas Watters (1904). "On Yuan Chwang's travels in India, 629–645 A.D." Royal Asiatic Society. p. 200.

Taken as Gandhavat the name is explained as meaning hsiang-hsing or "scent-action" from the word gandha which means scent, small, perfume.

At the Internet Archive. - Adrian Room (1997). Placenames of the World. McFarland. ISBN 9780786418145.

Kandahar. City, south central Afghanistan

At Google Books. - Macdonell, Arthur Anthony; Keith, Arthur Berriedale (1995). Vedic Index of Names and Subjects. Vol. 1. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. p. 219. ISBN 9788120813328. At Google Books.

- "Gandara - Livius".

- Herodotus (1920). "3.102.1". Histories. "4.44.2". Histories (in Greek). With an English translation by A. D. Godley.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) "3.102.1". Histories. "4.44.2". Histories. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. At the Perseus Project. - "The Book Of Duarte Barbosa Vol. 1". Internet Archive. p. 136, footnote 2. 1918.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - "Alexandria in Arachosia (Kandahar) - Livius". www.livius.org. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- Eggermont, Pierre Herman Leonard (1975), Alexander's Campaigns in Sind and Baluchistan and the Siege of the Brahmin Town of Harmatelia, Peeters Publishers, pp. 175–177, ISBN 978-90-6186-037-2

- "Catalogue of coins in the Punjab museum, Lahore". 1914.

- Olivieri, Luca M., Roberto Micheli, Massimo Vidale, and Muhammad Zahir, (2019). 'Late Bronze - Iron Age Swat Protohistoric Graves (Gandhara Grave Culture), Swat Valley, Pakistan (n-99)', in Narasimhan, Vagheesh M., et al., "Supplementary Materials for the formation of human populations in South and Central Asia", Science 365 (6 September 2019), pp. 137-164.

- Coningham, Robin, and Mark Manuel, (2008). "Kashmir and the Northwest Frontier", Asia, South, in Encyclopedia of Archaeology 2008, Elsevier, p. 740.

- Narasimhan, Vagheesh M., et al. (2019). "The formation of human populations in South and Central Asia", in Science 365 (6 September 2019), p. 11: "...we estimate the date of admixture into the Late Bronze Age and Iron Age individuals from the Swat District of northernmost South Asia to be, on average, 26 generations before the date that they lived, corresponding to a 95% confidence interval of ~1900 to 1500 BCE..."

- Macdonell, Arthur Anthony; Keith, Arthur Berriedale (1912). Vedic Index of Names and Subjects. John Murray. pp. 218–219.

- Chattopadhyaya, Sudhakar (1978). Reflections on the Tantras. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. p. 4.

- Raychaudhuri 1953, p. 59-62.

- Raychaudhuri 1953, p. 146-147.

- Prakash, Buddha (1951). "Poros". Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. 32 (1): 198–233. JSTOR 41784590. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- Macdonell & Keith 1912, p. 218-219, 432.

- Jain, Kailash Chand (1972). Malwa Through the Ages. Delhi, India: Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 98–104. ISBN 978-8-120-80824-9.

- Higham, Charles (2014), Encyclopedia of Ancient Asian Civilizations, Infobase Publishing, pp. 209–, ISBN 978-1-4381-0996-1

- Khoinaijam Rita Devi (1 January 2007). History of ancient India: on the basis of Buddhist literature. Akansha Publishing House. ISBN 978-81-8370-086-3.

- O. Bopearachchi, “Premières frappes locales de l’Inde du Nord-Ouest: nouvelles données,” in Trésors d’Orient: Mélanges offerts à Rika Gyselen, Fig. 1 CNG Coins

- Bopearachchi, Osmund. Coin Production and Circulation in Central Asia and North-West India (Before and after Alexander's Conquest). pp. 300–301.

- "US Department of Defense". Archived from the original on 10 June 2020. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- Errington, Elizabeth; Trust, Ancient India and Iran; Museum, Fitzwilliam (1992). The Crossroads of Asia: transformation in image and symbol in the art of ancient Afghanistan and Pakistan. Ancient India and Iran Trust. pp. 57–59. ISBN 9780951839911.

- Bopearachchi, Osmund. Coin Production and Circulation in Central Asia and North-West India (Before and after Alexander's Conquest). pp. 308–.

- Young, T. Cuyler (1988). "The early history of the Medes and the Persians and the Achaemenid empire to the death of Cambyses". In Boardman, John; Hammond, N. G. L.; Lewis, D. M.; Ostwald, M. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 4. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–52. ISBN 978-0-521-22804-6.

- Sethna, Kaikhosru Danjibuoy (2000). "To Pāṇini's Time from Pāṇini's Place". Problems of Ancient India. Aditya Prakashan. pp. 121–172. ISBN 978-8-177-42026-5.

- Bivar, A. D. H. (1988). "The Indus Lands". In Boardman, John; Hammond, N. G. L.; Lewis, D. M.; Ostwald, M. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 4. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 194–210. ISBN 978-0-521-22804-6.

- "Pukkusāti". www.palikanon.com. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- Rafi U. Samad, The Grandeur of Gandhara: The Ancient Buddhist Civilization of the Swat, Peshawar, Kabul and Indus Valleys. Algora Publishing, 2011, p. 32 ISBN 0875868592

- Mukerjee, R. K. History and Culture of Indian People, The Age of Imperial Unity, Foreign Invasion. p. 46.

- Curtius in McCrindle, p. 192, J. W. McCrindle; History of Punjab, Vol I, 1997, p 229, Punjabi University, Patiala (editors): Fauja Singh, L. M. Joshi; Kambojas Through the Ages, 2005, p. 134, Kirpal Singh.

- Revue des etudes grecques 1973, p 131, Ch-Em Ruelle, Association pour l'encouragement des etudes grecques en France.

- Early Indian Economic History, 1973, pp 237, 324, Rajaram Narayan Saletore.

- Myths of the Dog-man, 199, p 119, David Gordon White; Journal of the Oriental Institute, 1919, p 200; Journal of Indian Museums, 1973, p 2, Museums Association of India; The Pāradas: A Study in Their Coinage and History, 1972, p 52, Dr B. N. Mukherjee – Pāradas; Journal of the Department of Sanskrit, 1989, p 50, Rabindra Bharati University, Dept. of Sanskrit- Sanskrit literature; The Journal of Academy of Indian Numismatics & Sigillography, 1988, p 58, Academy of Indian Numismatics and Sigillography – Numismatics; Cf: Rivers of Life: Or Sources and Streams of the Faiths of Man in All Lands, 2002, p 114, J. G. R. Forlong.

- Journal of the Oriental Institute, 1919, p 265, Oriental Institute (Vadodara, India) – Oriental studies; For Kuru-Kamboja connections, see Dr Chandra Chakraberty's views in: Literary history of ancient India in relation to its racial and linguistic affiliations, pp 14,37, Vedas; The Racial History of India, 1944, p 153, Chandra Chakraberty – Ethnology; Paradise of Gods, 1966, p 330, Qamarud Din Ahmed – Pakistan.

- Ancient India, History of India for 1000 years, four Volumes, Vol I, 1938, pp 38, 98 Dr T. L. Shah.

- Rowland, Benjamin 1945 'Ganhdara and Early Christian Art: Buddha Palliatus', American Journal of Archaeology 49.4, 445–8

- Bracey, R 'Pilgrims Progress' Brief Guide to Kushan History Archived 12 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- Singh, Upinder (25 September 2017). Political Violence in Ancient India. p. 166. ISBN 9780674981287.

- Dani, Ahmad Hasan; Litvinsky, B. A. (1996). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The crossroads of civilizations, A.D. 250 to 750. UNESCO. p. 122. ISBN 9789231032110.

- "The entry of the Kidarites into India may firmly be placed some time round about the end of rule of Candragupta II or beginning of the rule of Kumaragupta I (circa 410-420 a.d.)" in Gupta, Parmeshwari Lal; Kulashreshtha, Sarojini (1994). Kuṣāṇa Coins and History. D.K. Printworld. p. 122. ISBN 9788124600177.

- "The Alchon Huns....established themselves as overlords of northwestern India, and directly contributed to the downfall of the Guptas" in Neelis, Jason (2010). Early Buddhist Transmission and Trade Networks: Mobility and Exchange Within and Beyond the Northwestern Borderlands of South Asia. BRILL. p. 162. ISBN 9789004181595.

- Bakker, Hans (2017), Monuments of Hope, Gloom and Glory in the Age of the Hunnic Wars: 50 years that changed India (484–534), Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, Section 4, ISBN 978-90-6984-715-3, archived from the original on 11 January 2020, retrieved 1 May 2021

- Atreyi Biswas (1971). The Political History of the Hūṇas in India. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. ISBN 9780883863015.

- Upendra Thakur (1967). The Hūṇas in India. Chowkhamba Prakashan. pp. 52–55.

- Upinder Singh (2017). Political Violence in Ancient India. Harvard University Press. p. 241. ISBN 9780674981287.

- Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 69–71. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

- Upinder Singh (2017). Political Violence in Ancient India. Harvard University Press. pp. 241–242. ISBN 9780674981287.

- Alberuni's India. (c. 1030 CE). Translated and annotated by Edward C. Sachau in two volumes. Kegana Paul, Trench, Trübner, London. (1910). Vol. I, p. 22.

- Henry Walter Bellow. The races of Afghanistan Being a brief account of the principal nations inhabiting that country. Asian Educational services. p. 73.

- Foundation, Encyclopaedia Iranica. "GĀNDHĀRĪ LANGUAGE". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Origins of Hindko".

- "Hindko and its links to Prakrit".

- "Origins of Hindko". doi:10.31826/jlr-2018-153-409. S2CID 212688313.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Rhie, Marylin Martin (15 July 2019). Early Buddhist Art of China and Central Asia, Volume 2 The Eastern Chin and Sixteen Kingdoms Period in China and Tumshuk, Kucha and Karashahr in Central Asia (2 vols). BRILL. p. 327. ISBN 978-90-04-39186-4.

- Dani, Ahmad Hasan (2001). History of Northern Areas of Pakistan: Upto 2000 A.D. Sang-e-Meel Publications. pp. 64–67. ISBN 978-969-35-1231-1.

- Saxena, Anju (12 May 2011). Himalayan Languages: Past and Present. Walter de Gruyter. p. 35. ISBN 978-3-11-089887-3.

- Liljegren, Henrik (26 February 2016). A grammar of Palula. Language Science Press. pp. 13–14. ISBN 978-3-946234-31-9.

Palula belongs to a group of Indo-Aryan (IA) languages spoken in the Hindukush region that are often referred to as “Dardic” languages... It has been and is still disputed to what extent this primarily geographically defined grouping has any real classificatory validity... On the one hand, Strand suggests that the term should be discarded altogether, holding that there is no justification whatsoever for any such grouping (in addition to the term itself having a problematic history of use), and prefers to make a finer classification of these languages into smaller genealogical groups directly under the IA heading, a classification we shall return to shortly... Zoller identifies the Dardic languages as the modern successors of the Middle Indo-Aryan (MIA) language Gandhari (also Gandhari Prakrit), but along with Bashir, Zoller concludes that the family tree model alone will not explain all the historical developments.

- Cacopardo, Alberto M.; Cacopardo, Augusto S. (2001). Gates of Peristan: History, Religion and Society in the Hindu Kush. IsIAO. p. 253. ISBN 978-88-6323-149-6.

...This leads us to the conclusion that the ancient dialects of the Peshawar District, the country between Tirah and Swât, must have belonged to the Tirahi-Kohistani type, and that the westernmost Dardic language, Pashai, which probably had its ancient centre in Laghmân, has enjoyed a comparatively independent position since early times". …Today the Kohistâni languages descendent from the ancient dialects that developed in these valleys have all been displaced from their original homelands, as described below.

- Burrow, T. (1936). "The Dialectical Position of the Niya Prakrit". Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London. 8 (2/3): 419–435. ISSN 1356-1898. JSTOR 608051.

... It might be going too far to say that Torwali is the direct lineal descendant of the Niya Prakrit, but there is no doubt that out of all the modern languages it shows the closest resemblance to it. A glance at the map in the Linguistic Survey of India shows that the area at present covered by "Kohistani" is the nearest to that area round Peshawar, where, as stated above, there is most reason to believe was the original home of the Niya Prakrit. That conclusion, which was reached for other reasons, is thus confirmed by the distribution of the modern dialects.

- Dani, Ahmad Hasan (2001). History of Northern Areas of Pakistan: Upto 2000 A.D. Sang-e-Meel Publications. p. 65. ISBN 978-969-35-1231-1.

In the Peshawar district, there does not remain any Indian dialect continuing this old Gandhari. The last to disappear was Tirahi, still spoken some years ago in Afghanistan, in the vicinity of Jalalabad, by descendants of migrants expelled from Tirah by the Afridis in the 19th century. Nowadays, it must be entirely extinct and in the NWFP are only to be found modern Iranian languages brought in by later immigrants (Baluch, Pashto) or Indian languages brought in by the paramount political power (Urdu, Panjabi) or by Hindu traders (Hindko).

- Jain, Danesh; Cardona, George (26 July 2007). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. p. 991. ISBN 978-1-135-79710-2.

- Salomon, Richard (10 December 1998). Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the other Indo-Aryan Languages. Oxford University Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-19-535666-3.

- "The Korean Buddhist Canon: A Descriptive Catalog (T. 361)".

- Mukherjee, Bratindra Nath. India in Early Central Asia. 1996. p. 15

- Williams, Paul. Mahāyāna Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations. 2008. p. 30

- Nakamura, Hajime. Indian Buddhism: A Survey With Biographical Notes. 1999. p. 205

- Williams, Paul. Mahāyāna Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations. 2008. p. 239

- "Gandharan Sculptural Style: The Buddha Image". Archived from the original on 18 December 2014. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- Ray, Reginald. Buddhist Saints in India: A Study in Buddhist Values and Orientations. 1999. p. 410

- Ray, Reginald. Buddhist Saints in India: A Study in Buddhist Values and Orientations. 1999. p. 426

- "EARLY HISTORY OF BUDDHISM | Facts and Details". Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- Malala Yousafzai (8 October 2013). I Am Malala: The Girl Who Stood Up for Education and Was Shot by the Taliban. Little, Brown. pp. 123–124. ISBN 978-0-316-32241-6.

The Taliban destroyed the Buddhist statues and stupas where we played Kushan kings haram Jehanabad Buddha.

- Wijewardena, W.A. (17 February 2014). "'I am Malala': But then, we all are Malalas, aren't we?". Daily FT.

- Wijewardena, W.A (17 February 2014). "'I am Malala': But Then, We All Are Malalas, Aren't We?". Colombo Telegraph.

- "Attack on giant Pakistan Buddha". BBC NEWS. 12 September 2007.

- "Another attack on the giant Buddha of Swat". AsiaNews.it. 10 November 2007.

- "Taliban and traffickers destroying Pakistan's Buddhist heritage". AsiaNews.it. 22 October 2012.

- "Schøyen Collection: Buddhism". Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- Bakshi, S.R. Kashmir: History and People. 1998. p. 194

- Behrendt, Kurt (2011). Gandharan Buddhism: Archaeology, Art, and Texts. UBC Press. p. 241. ISBN 978-0774841283. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- "Buddhism and Buddhist Art".

- Carlo Rosa; Thomas Theye; Simona Pannuzi (2019). "Geological overwiew of Gandharan sites and petrographical analysis on Gandharan stucco and clay artefacts" (pdf). Restauro Archeologico. Firenze University Press. 27 (1): Abstract. doi:10.13128/RA-25095. ISSN 1724-9686. OCLC 8349098991. Archived from the original on 15 February 2020. Retrieved 15 February 2020. on DOAJ

Sources

- Beal, Samuel. 1884. Si-Yu-Ki: Buddhist Records of the Western World, by Hiuen Tsiang. 2 vols. Trans. by Samuel Beal. London. Reprint: Delhi. Oriental Books Reprint Corporation. 1969.

- Beal, Samuel. 1911. The Life of Hiuen-Tsiang by the Shaman Hwui Li, with an Introduction containing an account of the Works of I-Tsing. Trans. by Samuel Beal. London. 1911. Reprint: Munshiram Manoharlal, New Delhi. 1973.

- Bellew, H.W. Kashmir and Kashgar. London, 1875. Reprint: Sang-e-Meel Publications 1999 ISBN 969-35-0738-X

- Caroe, Sir Olaf, The Pathans, Oxford University Press, Karachi, 1958.

- Eggermont, Pierre Herman Leonard (1975), Alexander's Campaigns in Sind and Baluchistan and the Siege of the Brahmin Town of Harmatelia, Peeters Publishers, ISBN 978-90-6186-037-2

- Herodotus (1920). Histories (in Greek and English). With an English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Hill, John E. 2003. "Annotated Translation of the Chapter on the Western Regions according to the Hou Hanshu". 2nd Edition: Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes, 1st to 2nd Centuries CE. 2015. John E. Hill. Volume I, ISBN 978-1500696702; Volume II, ISBN 978-1503384620. CreateSpace, North Charleston, S.C.

- Hussain, J. An Illustrated History of Pakistan, Oxford University Press, Karachi, 1983.

- Legge, James. Trans. and ed. 1886. A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms: being an account by the Chinese monk Fâ-hsien of his travels in India and Ceylon (A.D. 399–414) in search of the Buddhist Books of Discipline. Reprint: Dover Publications, New York. 1965.

- Neelis, Jason (2010), Early Buddhist Transmission and Trade Networks: Mobility and Exchange Within and Beyond the Northwestern Borderlands of South Asia, BRILL, ISBN 978-90-04-18159-5

- Raychaudhuri, Hemchandra (1953). Political History of Ancient India: From the Accession of Parikshit to the Extinction of Gupta Dynasty. University of Calcutta.

- Shaw, Isobel. Pakistan Handbook, The Guidebook Co., Hong Kong, 1989

- Watters, Thomas. 1904–5. On Yuan Chwang's Travels in India (A.D. 629–645). Reprint: Mushiram Manoharlal Publishers, New Delhi. 1973.

Further reading

- Lerner, Martin (1984). The flame and the lotus: Indian and Southeast Asian art from the Kronos collections. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0-87099-374-7.

- Rehman, Abdur (2009). "A Note on the Etymology of Gandhāra". Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 23: 143–146. JSTOR 24049432.

- Filigenzi, Anna (2000). "Reviewed Work: A Catalogue of the Gandhāra Sculpture in the British Museum, Vol. I: Text, Vol. II: Plates by Wladimir Zwalf". Wladimir Zwalf, Review by: Anna Filigenzi. Istituto Italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente (IsIAO). 50 (1/4): 584–586. JSTOR 29757475.

- Rienjang, Wannaporn, and Peter Stewart (eds), The Rediscovery and Reception of Gandharan Art (Archaeopress, 2022) ISBN 978-1-80327-233-7.

External links

- Gandharan Connections Project (Cambridge, 2016-2021)

- Livius.org: Gandara

- The Buddhist Manuscript project

- University of Washington's Gandharan manuscript

- Coins of Gandhara janapada

- Gandhara Civilization- National Fund for Cultural Heritage (Pakistan)