Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (/ˈɡɑːndi, ˈɡændi/;[3] GAHN-dee; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948) was an Indian lawyer,[4] anti-colonial nationalist[5] and political ethicist[6] who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful campaign for India's independence from British rule,[7] and to later inspire movements for civil rights and freedom across the world. The honorific Mahātmā (Sanskrit: "great-souled", "venerable"), first applied to him in 1914 in South Africa, is now used throughout the world.[8][9]

Mahātmā Gandhi | |

|---|---|

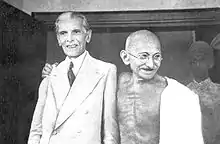

Gandhi in London, 1931 | |

| Born | Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi 2 October 1869 Porbandar, Porbandar State, Kathiawar Agency, British Raj |

| Died | 30 January 1948 (aged 78) New Delhi, Dominion of India |

| Cause of death | Assassination (gunshot wounds) |

| Monuments |

|

| Citizenship |

|

| Alma mater |

|

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 1893–1948 |

| Era | British Raj |

| Known for |

|

| Notable work | The Story of My Experiments with Truth |

| Political party | Indian National Congress (1920–1934)[1] |

| Movement | Indian independence movement |

| Spouse | Kasturba Gandhi

(m. 1883; died 1944) |

| Children |

|

| Parents |

|

| Relatives | See Family of Mahatma Gandhi C. Rajagopalachari (father-in-law of Gandhi's son Devdas) |

| Awards | Time Person of the Year (1930)[2] |

| 43rd President of the Indian National Congress | |

| In office 1924 | |

| Preceded by | Abul Kalam Azad |

| Succeeded by | Sarojini Naidu |

| Signature | |

| |

Born and raised in a Hindu family in coastal Gujarat, Gandhi trained in the law at the Inner Temple, London, and was called to the bar at age 22 in June 1891. After two uncertain years in India, where he was unable to start a successful law practice, he moved to South Africa in 1893 to represent an Indian merchant in a lawsuit. He went on to live in South Africa for 21 years. It was here that Gandhi raised a family and first employed nonviolent resistance in a campaign for civil rights. In 1915, aged 45, he returned to India and soon set about organising peasants, farmers, and urban labourers to protest against excessive land-tax and discrimination.

Assuming leadership of the Indian National Congress in 1921, Gandhi led nationwide campaigns for easing poverty, expanding women's rights, building religious and ethnic amity, ending untouchability, and, above all, achieving swaraj or self-rule. Gandhi adopted the short dhoti woven with hand-spun yarn as a mark of identification with India's rural poor. He began to live in a self-sufficient residential community, to eat simple food, and undertake long fasts as a means of both introspection and political protest. Bringing anti-colonial nationalism to the common Indians, Gandhi led them in challenging the British-imposed salt tax with the 400 km (250 mi) Dandi Salt March in 1930 and in calling for the British to quit India in 1942. He was imprisoned many times and for many years in both South Africa and India.

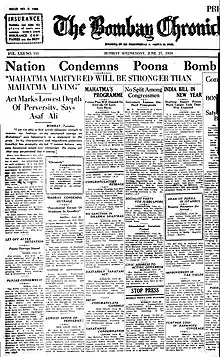

Gandhi's vision of an independent India based on religious pluralism was challenged in the early 1940s by a Muslim nationalism which demanded a separate homeland for Muslims within British India.[10] In August 1947, Britain granted independence, but the British Indian Empire[10] was partitioned into two dominions, a Hindu-majority India and a Muslim-majority Pakistan.[11] As many displaced Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs made their way to their new lands, religious violence broke out, especially in the Punjab and Bengal. Abstaining from the official celebration of independence, Gandhi visited the affected areas, attempting to alleviate distress. In the months following, he undertook several hunger strikes to stop the religious violence. The last of these, begun in Delhi on 12 January 1948 when he was 78,[12] also had the indirect goal of pressuring India to pay out some cash assets owed to Pakistan.[12] Although the Government of India relented, as did the religious rioters, the belief that Gandhi had been too resolute in his defence of both Pakistan and Indian Muslims, especially those besieged in Delhi, spread among some Hindus in India.[13][12] Among these was Nathuram Godse, a militant Hindu nationalist from western India, who assassinated Gandhi by firing three bullets into his chest at an interfaith prayer meeting in Delhi on 30 January 1948.[14]

Gandhi's birthday, 2 October, is commemorated in India as Gandhi Jayanti, a national holiday, and worldwide as the International Day of Nonviolence. Gandhi is commonly, though not formally, considered the Father of the Nation in India[15][16] and was commonly called Bapu[17] (Gujarati: endearment for father,[18] papa[18][19]).

Biography

Early life and background

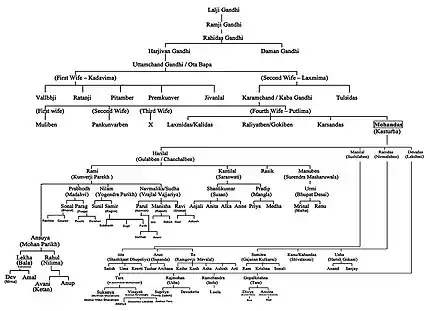

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi[20] was born on 2 October 1869[21] into a Gujarati Hindu Modh Bania family[22][23] in Porbandar (also known as Sudamapuri), a coastal town on the Kathiawar Peninsula and then part of the small princely state of Porbandar in the Kathiawar Agency of the British Raj. His father, Karamchand Uttamchand Gandhi (1822–1885), served as the dewan (chief minister) of Porbandar state.[24][25] His family originated from the then village of Kutiana in what was then Junagadh State.[26]

Although he only had an elementary education and had previously been a clerk in the state administration, Karamchand proved a capable chief minister.[27] During his tenure, Karamchand married four times. His first two wives died young, after each had given birth to a daughter, and his third marriage was childless. In 1857, Karamchand sought his third wife's permission to remarry; that year, he married Putlibai (1844–1891), who also came from Junagadh,[27] and was from a Pranami Vaishnava family.[28] Karamchand and Putlibai had three children over the ensuing decade: a son, Laxmidas (c. 1860–1914); a daughter, Raliatbehn (1862–1960); and another son, Karsandas (c. 1866–1913).[29][30]

On 2 October 1869, Putlibai gave birth to her last child, Mohandas, in a dark, windowless ground-floor room of the Gandhi family residence in Porbandar city. As a child, Gandhi was described by his sister Raliat as "restless as mercury, either playing or roaming about. One of his favourite pastimes was twisting dogs' ears."[31] The Indian classics, especially the stories of Shravana and king Harishchandra, had a great impact on Gandhi in his childhood. In his autobiography, he admits that they left an indelible impression on his mind. He writes: "It haunted me and I must have acted Harishchandra to myself times without number." Gandhi's early self-identification with truth and love as supreme values is traceable to these epic characters.[32][33]

The family's religious background was eclectic. Gandhi's father Karamchand was Hindu and his mother Putlibai was from a Pranami Vaishnava Hindu family.[34][35] Gandhi's father was of Modh Baniya caste in the varna of Vaishya.[36] His mother came from the medieval Krishna bhakti-based Pranami tradition, whose religious texts include the Bhagavad Gita, the Bhagavata Purana, and a collection of 14 texts with teachings that the tradition believes to include the essence of the Vedas, the Quran and the Bible.[35][37] Gandhi was deeply influenced by his mother, an extremely pious lady who "would not think of taking her meals without her daily prayers... she would take the hardest vows and keep them without flinching. To keep two or three consecutive fasts was nothing to her."[38]

In 1874, Gandhi's father Karamchand left Porbandar for the smaller state of Rajkot, where he became a counsellor to its ruler, the Thakur Sahib; though Rajkot was a less prestigious state than Porbandar, the British regional political agency was located there, which gave the state's diwan a measure of security.[39] In 1876, Karamchand became diwan of Rajkot and was succeeded as diwan of Porbandar by his brother Tulsidas. His family then rejoined him in Rajkot.[40]

At age 9, Gandhi entered the local school in Rajkot, near his home. There he studied the rudiments of arithmetic, history, the Gujarati language and geography.[40] At age 11, he joined the High School in Rajkot, Alfred High School.[42] He was an average student, won some prizes, but was a shy and tongue tied student, with no interest in games; his only companions were books and school lessons.[43]

In May 1883, the 13-year-old Mohandas was married to 14-year-old Kasturbai Makhanji Kapadia (her first name was usually shortened to "Kasturba", and affectionately to "Ba") in an arranged marriage, according to the custom of the region at that time.[44] In the process, he lost a year at school but was later allowed to make up by accelerating his studies.[45] His wedding was a joint event, where his brother and cousin were also married. Recalling the day of their marriage, he once said, "As we didn't know much about marriage, for us it meant only wearing new clothes, eating sweets and playing with relatives." As was prevailing tradition, the adolescent bride was to spend much time at her parents' house, and away from her husband.[46]

Writing many years later, Mohandas described with regret the lustful feelings he felt for his young bride, "even at school I used to think of her, and the thought of nightfall and our subsequent meeting was ever haunting me." He later recalled feeling jealous and possessive of her, such as when she would visit a temple with her girlfriends, and being sexually lustful in his feelings for her.[47]

In late 1885, Gandhi's father Karamchand died.[48] Gandhi, then 16 years old, and his wife of age 17 had their first baby, who survived only a few days. The two deaths anguished Gandhi.[48] The Gandhi couple had four more children, all sons: Harilal, born in 1888; Manilal, born in 1892; Ramdas, born in 1897; and Devdas, born in 1900.[44]

In November 1887, the 18-year-old Gandhi graduated from high school in Ahmedabad.[49] In January 1888, he enrolled at Samaldas College in Bhavnagar State, then the sole degree-granting institution of higher education in the region. But he dropped out and returned to his family in Porbandar.[50]

Student of law

Gandhi had dropped out of the cheapest college he could afford in Bombay.[51] Mavji Dave Joshiji, a Brahmin priest and family friend, advised Gandhi and his family that he should consider law studies in London.[52] In July 1888, his wife Kasturba gave birth to their first surviving son, Harilal.[53] His mother was not comfortable about Gandhi leaving his wife and family, and going so far from home. Gandhi's uncle Tulsidas also tried to dissuade his nephew. Gandhi wanted to go. To persuade his wife and mother, Gandhi made a vow in front of his mother that he would abstain from meat, alcohol and women. Gandhi's brother Laxmidas, who was already a lawyer, cheered Gandhi's London studies plan and offered to support him. Putlibai gave Gandhi her permission and blessing.[50][54]

On 10 August 1888, Gandhi aged 18, left Porbandar for Mumbai, then known as Bombay. Upon arrival, he stayed with the local Modh Bania community whose elders warned him that England would tempt him to compromise his religion, and eat and drink in Western ways. Despite Gandhi informing them of his promise to his mother and her blessings, he was excommunicated from his caste. Gandhi ignored this, and on 4 September, he sailed from Bombay to London, with his brother seeing him off.[53][55] Gandhi attended University College, London, a constituent college of the University of London.

At UCL, he studied law and jurisprudence and was invited to enrol at Inner Temple with the intention of becoming a barrister. His childhood shyness and self-withdrawal had continued through his teens. He retained these traits when he arrived in London, but joined a public speaking practice group and overcame his shyness sufficiently to practise law.[56]

He demonstrated a keen interest in the welfare of London’s impoverished dockland communities. In 1889, a bitter trade dispute broke out in London, with dockers striking for better pay and conditions, and seamen, shipbuilders, factory girls and other joining the strike in solidarity. The strikers were successful, in part due to the mediation of Cardinal Manning, leading Gandhi and an Indian friend to make a point of visiting the cardinal and thanking him for his work.[57]

Vegetarianism and committee work

Gandhi's time in London was influenced by the vow he had made to his mother. He tried to adopt "English" customs, including taking dancing lessons. However, he did not appreciate the bland vegetarian food offered by his landlady and was frequently hungry until he found one of London's few vegetarian restaurants. Influenced by Henry Salt's writing, he joined the London Vegetarian Society and was elected to its executive committee[58] under the aegis of its president and benefactor Arnold Hills. An achievement while on the committee was the establishment of a Bayswater chapter.[59] Some of the vegetarians he met were members of the Theosophical Society, which had been founded in 1875 to further universal brotherhood, and which was devoted to the study of Buddhist and Hindu literature. They encouraged Gandhi to join them in reading the Bhagavad Gita both in translation as well as in the original.[58]

Gandhi had a friendly and productive relationship with Hills, but the two men took a different view on the continued LVS membership of fellow committee member Thomas Allinson. Their disagreement is the first known example of Gandhi challenging authority, despite his shyness and temperamental disinclination towards confrontation.

Allinson had been promoting newly available birth control methods, but Hills disapproved of these, believing they undermined public morality. He believed vegetarianism to be a moral movement and that Allinson should therefore no longer remain a member of the LVS. Gandhi shared Hills' views on the dangers of birth control, but defended Allinson's right to differ.[60] It would have been hard for Gandhi to challenge Hills; Hills was 12 years his senior and unlike Gandhi, highly eloquent. He bankrolled the LVS and was a captain of industry with his Thames Ironworks company employing more than 6,000 people in the East End of London. He was also a highly accomplished sportsman who later founded the football club West Ham United. In his 1927 An Autobiography, Vol. I, Gandhi wrote:

The question deeply interested me...I had a high regard for Mr. Hills and his generosity. But I thought it was quite improper to exclude a man from a vegetarian society simply because he refused to regard puritan morals as one of the objects of the society[60]

A motion to remove Allinson was raised, and was debated and voted on by the committee. Gandhi's shyness was an obstacle to his defence of Allinson at the committee meeting. He wrote his views down on paper but shyness prevented him from reading out his arguments, so Hills, the President, asked another committee member to read them out for him. Although some other members of the committee agreed with Gandhi, the vote was lost and Allinson excluded. There were no hard feelings, with Hills proposing the toast at the LVS farewell dinner in honour of Gandhi's return to India.[61]

Called to the bar

Gandhi, at age 22, was called to the bar in June 1891 and then left London for India, where he learned that his mother had died while he was in London and that his family had kept the news from him.[58] His attempts at establishing a law practice in Bombay failed because he was psychologically unable to cross-examine witnesses. He returned to Rajkot to make a modest living drafting petitions for litigants, but he was forced to stop when he ran afoul of a British officer Sam Sunny.[59][58]

In 1893, a Muslim merchant in Kathiawar named Dada Abdullah contacted Gandhi. Abdullah owned a large successful shipping business in South Africa. His distant cousin in Johannesburg needed a lawyer, and they preferred someone with Kathiawari heritage. Gandhi inquired about his pay for the work. They offered a total salary of £105 (~$17,200 in 2019 money) plus travel expenses. He accepted it, knowing that it would be at least a one-year commitment in the Colony of Natal, South Africa, also a part of the British Empire.[59][62]

Civil rights activist in South Africa (1893–1914)

In April 1893, Gandhi aged 23, set sail for South Africa to be the lawyer for Abdullah's cousin.[62][63] He spent 21 years in South Africa, where he developed his political views, ethics and politics.[64][65]

Immediately upon arriving in South Africa, Gandhi faced discrimination because of his skin colour and heritage, like all people of colour.[66] He was not allowed to sit with European passengers in the stagecoach and told to sit on the floor near the driver, then beaten when he refused; elsewhere he was kicked into a gutter for daring to walk near a house, in another instance thrown off a train at Pietermaritzburg after refusing to leave the first-class.[67][68] He sat in the train station, shivering all night and pondering if he should return to India or protest for his rights.[68] He chose to protest and was allowed to board the train the next day.[69] In another incident, the magistrate of a Durban court ordered Gandhi to remove his turban, which he refused to do.[70] Indians were not allowed to walk on public footpaths in South Africa. Gandhi was kicked by a police officer out of the footpath onto the street without warning.[71]

When Gandhi arrived in South Africa, according to Herman, he thought of himself as "a Briton first, and an Indian second".[72] However, the prejudice against him and his fellow Indians from British people that Gandhi experienced and observed deeply bothered him. He found it humiliating, struggling to understand how some people can feel honour or superiority or pleasure in such inhumane practices.[68] Gandhi began to question his people's standing in the British Empire.[73]

The Abdullah case that had brought him to South Africa concluded in May 1894, and the Indian community organised a farewell party for Gandhi as he prepared to return to India.[74] However, a new Natal government discriminatory proposal led to Gandhi extending his original period of stay in South Africa. He planned to assist Indians in opposing a bill to deny them the right to vote, a right then proposed to be an exclusive European right. He asked Joseph Chamberlain, the British Colonial Secretary, to reconsider his position on this bill.[64] Though unable to halt the bill's passage, his campaign was successful in drawing attention to the grievances of Indians in South Africa. He helped found the Natal Indian Congress in 1894,[59][69] and through this organisation, he moulded the Indian community of South Africa into a unified political force. In January 1897, when Gandhi landed in Durban, a mob of white settlers attacked him[75] and he escaped only through the efforts of the wife of the police superintendent. However, he refused to press charges against any member of the mob.[59]

During the Boer War, Gandhi volunteered in 1900 to form a group of stretcher-bearers as the Natal Indian Ambulance Corps. According to Arthur Herman, Gandhi wanted to disprove the British colonial stereotype that Hindus were not fit for "manly" activities involving danger and exertion, unlike the Muslim "martial races".[76] Gandhi raised eleven hundred Indian volunteers, to support British combat troops against the Boers. They were trained and medically certified to serve on the front lines. They were auxiliaries at the Battle of Colenso to a White volunteer ambulance corps. At the battle of Spion Kop Gandhi and his bearers moved to the front line and had to carry wounded soldiers for miles to a field hospital because the terrain was too rough for the ambulances. Gandhi and thirty-seven other Indians received the Queen's South Africa Medal.[77][78]

In 1906, the Transvaal government promulgated a new Act compelling registration of the colony's Indian and Chinese populations. At a mass protest meeting held in Johannesburg on 11 September that year, Gandhi adopted his still evolving methodology of Satyagraha (devotion to the truth), or nonviolent protest, for the first time.[79] According to Anthony Parel, Gandhi was also influenced by the Tamil moral text Tirukkuṛaḷ after Leo Tolstoy mentioned it in their correspondence that began with "A Letter to a Hindu".[80][81] Gandhi urged Indians to defy the new law and to suffer the punishments for doing so. Gandhi's ideas of protests, persuasion skills and public relations had emerged. He took these back to India in 1915.[82][83]

Europeans, Indians and Africans

Gandhi focused his attention on Indians while in South Africa. He initially was not interested in politics. This changed, however, after he was discriminated against and bullied, such as by being thrown out of a train coach because of his skin colour by a white train official. After several such incidents with Whites in South Africa, Gandhi's thinking and focus changed, and he felt he must resist this and fight for rights. He entered politics by forming the Natal Indian Congress.[84] According to Ashwin Desai and Goolam Vahed, Gandhi's views on racism are contentious, and in some cases, distressing to those who admire him. Gandhi suffered persecution from the beginning in South Africa. Like with other coloured people, white officials denied him his rights, and the press and those in the streets bullied and called him a "parasite", "semi-barbarous", "canker", "squalid coolie", "yellow man", and other epithets. People would spit on him as an expression of racial hate.[85]

While in South Africa, Gandhi focused on racial persecution of Indians but ignored those of Africans. In some cases, state Desai and Vahed, his behaviour was one of being a willing part of racial stereotyping and African exploitation.[85] During a speech in September 1896, Gandhi complained that the whites in the British colony of South Africa were degrading Indian Hindus and Muslims to "a level of Kaffir".[86] Scholars cite it as an example of evidence that Gandhi at that time thought of Indians and black South Africans differently.[85] As another example given by Herman, Gandhi, at age 24, prepared a legal brief for the Natal Assembly in 1895, seeking voting rights for Indians. Gandhi cited race history and European Orientalists' opinions that "Anglo-Saxons and Indians are sprung from the same Aryan stock or rather the Indo-European peoples", and argued that Indians should not be grouped with the Africans.[74]

Years later, Gandhi and his colleagues served and helped Africans as nurses and by opposing racism, according to the Nobel Peace Prize winner Nelson Mandela. The general image of Gandhi, state Desai and Vahed, has been reinvented since his assassination as if he was always a saint when in reality his life was more complex, contained inconvenient truths and was one that evolved over time.[85] In contrast, other Africa scholars state the evidence points to a rich history of co-operation and efforts by Gandhi and Indian people with nonwhite South Africans against persecution of Africans and the Apartheid.[87]

In 1906, when the Bambatha Rebellion broke out in the colony of Natal, then 36-year old Gandhi, despite sympathising with the Zulu rebels encouraged Indian South Africans to form a volunteer stretcher-bearer unit.[88] Writing in the Indian Opinion, Gandhi argued that military service would be beneficial to the Indian community and claimed it would give them "health and happiness."[89] Gandhi eventually led a volunteer mixed unit of Indian and African stretcher-bearers to treat wounded combatants during the suppression of the rebellion.[88]

The medical unit commanded by Gandhi operated for less than two months before being disbanded.[88] After the suppression of the rebellion, the colonial establishment showed no interest in extending to the Indian community the civil rights granted to white South Africans. This led Gandhi to becoming disillusioned with the Empire and aroused a spiritual awakening with him; historian Arthur L. Herman wrote that his African experience was a part of his great disillusionment with the West, transforming him into an "uncompromising non-cooperator".[89]

In 1910, Gandhi established, with the help of his friend Hermann Kallenbach, an idealistic community they named Tolstoy Farm near Johannesburg.[90] There he nurtured his policy of peaceful resistance.[91]

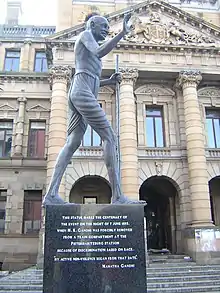

In the years after black South Africans gained the right to vote in South Africa (1994), Gandhi was proclaimed a national hero with numerous monuments.[92]

Struggle for Indian independence (1915–1947)

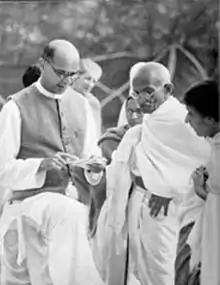

At the request of Gopal Krishna Gokhale, conveyed to him by C. F. Andrews, Gandhi returned to India in 1915. He brought an international reputation as a leading Indian nationalist, theorist and community organiser.

Gandhi joined the Indian National Congress and was introduced to Indian issues, politics and the Indian people primarily by Gokhale. Gokhale was a key leader of the Congress Party best known for his restraint and moderation, and his insistence on working inside the system. Gandhi took Gokhale's liberal approach based on British Whiggish traditions and transformed it to make it look Indian.[93]

Gandhi took leadership of the Congress in 1920 and began escalating demands until on 26 January 1930 the Indian National Congress declared the independence of India. The British did not recognise the declaration but negotiations ensued, with the Congress taking a role in provincial government in the late 1930s. Gandhi and the Congress withdrew their support of the Raj when the Viceroy declared war on Germany in September 1939 without consultation. Tensions escalated until Gandhi demanded immediate independence in 1942 and the British responded by imprisoning him and tens of thousands of Congress leaders. Meanwhile, the Muslim League did co-operate with Britain and moved, against Gandhi's strong opposition, to demands for a totally separate Muslim state of Pakistan. In August 1947 the British partitioned the land with India and Pakistan each achieving independence on terms that Gandhi disapproved.[94]

Role in World War I

In April 1918, during the latter part of World War I, the Viceroy invited Gandhi to a War Conference in Delhi.[95] Gandhi agreed to actively recruit Indians for the war effort.[96][97] In contrast to the Zulu War of 1906 and the outbreak of World War I in 1914, when he recruited volunteers for the Ambulance Corps, this time Gandhi attempted to recruit combatants. In a June 1918 leaflet entitled "Appeal for Enlistment", Gandhi wrote "To bring about such a state of things we should have the ability to defend ourselves, that is, the ability to bear arms and to use them... If we want to learn the use of arms with the greatest possible despatch, it is our duty to enlist ourselves in the army."[98] He did, however, stipulate in a letter to the Viceroy's private secretary that he "personally will not kill or injure anybody, friend or foe."[99]

Gandhi's war recruitment campaign brought into question his consistency on nonviolence. Gandhi's private secretary noted that "The question of the consistency between his creed of 'Ahimsa' (nonviolence) and his recruiting campaign was raised not only then but has been discussed ever since."[96]

Champaran agitations

Gandhi's first major achievement came in 1917 with the Champaran agitation in Bihar. The Champaran agitation pitted the local peasantry against largely Anglo-Indian plantation owners who were backed by the local administration. The peasants were forced to grow Indigofera, a cash crop for Indigo dye whose demand had been declining over two decades, and were forced to sell their crops to the planters at a fixed price. Unhappy with this, the peasantry appealed to Gandhi at his ashram in Ahmedabad. Pursuing a strategy of nonviolent protest, Gandhi took the administration by surprise and won concessions from the authorities.[100]

Kheda agitations

In 1918, Kheda was hit by floods and famine and the peasantry was demanding relief from taxes. Gandhi moved his headquarters to Nadiad,[101] organising scores of supporters and fresh volunteers from the region, the most notable being Vallabhbhai Patel.[102] Using non-co-operation as a technique, Gandhi initiated a signature campaign where peasants pledged non-payment of revenue even under the threat of confiscation of land. A social boycott of mamlatdars and talatdars (revenue officials within the district) accompanied the agitation. Gandhi worked hard to win public support for the agitation across the country. For five months, the administration refused, but by the end of May 1918, the Government gave way on important provisions and relaxed the conditions of payment of revenue tax until the famine ended. In Kheda, Vallabhbhai Patel represented the farmers in negotiations with the British, who suspended revenue collection and released all the prisoners.[103]

Khilafat movement

Every revolution begins with a single act of defiance.

In 1919, following World War I, Gandhi (aged 49) sought political co-operation from Muslims in his fight against British imperialism by supporting the Ottoman Empire that had been defeated in the World War. Before this initiative of Gandhi, communal disputes and religious riots between Hindus and Muslims were common in British India, such as the riots of 1917–18. Gandhi had already supported the British crown with resources and by recruiting Indian soldiers to fight the war in Europe on the British side. This effort of Gandhi was in part motivated by the British promise to reciprocate the help with swaraj (self-government) to Indians after the end of World War I.[104] The British government, instead of self government, had offered minor reforms instead, disappointing Gandhi.[105] Gandhi announced his satyagraha (civil disobedience) intentions. The British colonial officials made their counter move by passing the Rowlatt Act, to block Gandhi's movement. The Act allowed the British government to treat civil disobedience participants as criminals and gave it the legal basis to arrest anyone for "preventive indefinite detention, incarceration without judicial review or any need for a trial".[106]

Gandhi felt that Hindu-Muslim co-operation was necessary for political progress against the British. He leveraged the Khilafat movement, wherein Sunni Muslims in India, their leaders such as the sultans of princely states in India and Ali brothers championed the Turkish Caliph as a solidarity symbol of Sunni Islamic community (ummah). They saw the Caliph as their means to support Islam and the Islamic law after the defeat of Ottoman Empire in World War I.[107][108][109] Gandhi's support to the Khilafat movement led to mixed results. It initially led to a strong Muslim support for Gandhi. However, the Hindu leaders including Rabindranath Tagore questioned Gandhi's leadership because they were largely against recognising or supporting the Sunni Islamic Caliph in Turkey.[lower-alpha 1]

The increasing Muslim support for Gandhi, after he championed the Caliph's cause, temporarily stopped the Hindu-Muslim communal violence. It offered evidence of inter-communal harmony in joint Rowlatt satyagraha demonstration rallies, raising Gandhi's stature as the political leader to the British.[113][114] His support for the Khilafat movement also helped him sideline Muhammad Ali Jinnah, who had announced his opposition to the satyagraha non-co-operation movement approach of Gandhi. Jinnah began creating his independent support, and later went on to lead the demand for West and East Pakistan. Though they agreed in general terms on Indian independence, they disagreed on the means of achieving this. Jinnah was mainly interested in dealing with the British via constitutional negotiation, rather than attempting to agitate the masses.[115][116][117]

By the end of 1922 the Khilafat movement had collapsed.[118] Turkey's Atatürk had ended the Caliphate, Khilafat movement ended, and Muslim support for Gandhi largely evaporated.[108][109] Muslim leaders and delegates abandoned Gandhi and his Congress.[119] Hindu-Muslim communal conflicts reignited. Deadly religious riots re-appeared in numerous cities, with 91 in United Provinces of Agra and Oudh alone.[120][121]

Non-co-operation

With his book Hind Swaraj (1909) Gandhi, aged 40, declared that British rule was established in India with the co-operation of Indians and had survived only because of this co-operation. If Indians refused to co-operate, British rule would collapse and swaraj (Indian independence) would come.[122]

In February 1919, Gandhi cautioned the Viceroy of India with a cable communication that if the British were to pass the Rowlatt Act, he would appeal to Indians to start civil disobedience.[123] The British government ignored him and passed the law, stating it would not yield to threats. The satyagraha civil disobedience followed, with people assembling to protest the Rowlatt Act. On 30 March 1919, British law officers opened fire on an assembly of unarmed people, peacefully gathered, participating in satyagraha in Delhi.[123]

People rioted in retaliation. On 6 April 1919, a Hindu festival day, he asked a crowd to remember not to injure or kill British people, but to express their frustration with peace, to boycott British goods and burn any British clothing they owned. He emphasised the use of non-violence to the British and towards each other, even if the other side used violence. Communities across India announced plans to gather in greater numbers to protest. Government warned him to not enter Delhi. Gandhi defied the order. On 9 April, Gandhi was arrested.[123]

People rioted. On 13 April 1919, people including women with children gathered in an Amritsar park, and British Indian Army officer Reginald Dyer surrounded them and ordered troops under his command to fire on them. The resulting Jallianwala Bagh massacre (or Amritsar massacre) of hundreds of Sikh and Hindu civilians enraged the subcontinent, but was supported by some Britons and parts of the British media as a necessary response. Gandhi in Ahmedabad, on the day after the massacre in Amritsar, did not criticise the British and instead criticised his fellow countrymen for not exclusively using 'love' to deal with the 'hate' of the British government.[123] Gandhi demanded that the Indian people stop all violence, stop all property destruction, and went on fast-to-death to pressure Indians to stop their rioting.[124]

The massacre and Gandhi's non-violent response to it moved many, but also made some Sikhs and Hindus upset that Dyer was getting away with murder. Investigation committees were formed by the British, which Gandhi asked Indians to boycott.[123] The unfolding events, the massacre and the British response, led Gandhi to the belief that Indians will never get a fair equal treatment under British rulers, and he shifted his attention to swaraj and political independence for India.[125] In 1921, Gandhi was the leader of the Indian National Congress.[109] He reorganised the Congress. With Congress now behind him, and Muslim support triggered by his backing the Khilafat movement to restore the Caliph in Turkey,[109] Gandhi had the political support and the attention of the British Raj.[112][106][108]

Gandhi expanded his nonviolent non-co-operation platform to include the swadeshi policy – the boycott of foreign-made goods, especially British goods. Linked to this was his advocacy that khadi (homespun cloth) be worn by all Indians instead of British-made textiles. Gandhi exhorted Indian men and women, rich or poor, to spend time each day spinning khadi in support of the independence movement.[126] In addition to boycotting British products, Gandhi urged the people to boycott British institutions and law courts, to resign from government employment, and to forsake British titles and honours. Gandhi thus began his journey aimed at crippling the British India government economically, politically and administratively.[127]

The appeal of "Non-cooperation" grew, its social popularity drew participation from all strata of Indian society. Gandhi was arrested on 10 March 1922, tried for sedition, and sentenced to six years' imprisonment. He began his sentence on 18 March 1922. With Gandhi isolated in prison, the Indian National Congress split into two factions, one led by Chitta Ranjan Das and Motilal Nehru favouring party participation in the legislatures, and the other led by Chakravarti Rajagopalachari and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, opposing this move.[128] Furthermore, co-operation among Hindus and Muslims ended as Khilafat movement collapsed with the rise of Atatürk in Turkey. Muslim leaders left the Congress and began forming Muslim organisations. The political base behind Gandhi had broken into factions. Gandhi was released in February 1924 for an appendicitis operation, having served only two years.[129][130]

Salt Satyagraha (Salt March)

After his early release from prison for political crimes in 1924, over the second half of the 1920s Gandhi continued to pursue swaraj. He pushed through a resolution at the Calcutta Congress in December 1928 calling on the British government to grant India dominion status or face a new campaign of non-cooperation with complete independence for the country as its goal.[131] After his support for World War I with Indian combat troops, and the failure of Khilafat movement in preserving the rule of Caliph in Turkey, followed by a collapse in Muslim support for his leadership, some such as Subhas Chandra Bose and Bhagat Singh questioned his values and non-violent approach.[108][132] While many Hindu leaders championed a demand for immediate independence, Gandhi revised his own call to a one-year wait, instead of two.[131]

The British did not respond favourably to Gandhi's proposal. British political leaders such as Lord Birkenhead and Winston Churchill announced opposition to "the appeasers of Gandhi" in their discussions with European diplomats who sympathised with Indian demands.[133] On 31 December 1929, an Indian flag was unfurled in Lahore. Gandhi led Congress in a celebration on 26 January 1930 of India's Independence Day in Lahore. This day was commemorated by almost every other Indian organisation. Gandhi then launched a new Satyagraha against the British salt tax in March 1930. Gandhi sent an ultimatum in the form of a letter personally addressed to Lord Irwin, the viceroy of India, on 2 March. Gandhi condemned British rule in the letter, describing it as "a curse" that "has impoverished the dumb millions by a system of progressive exploitation and by a ruinously expensive military and civil administration...It has reduced us politically to serfdom." Gandhi also mentioned in the letter that the viceroy received a salary "over five thousand times India's average income." In the letter, Gandhi also stressed his continued adherence to non-violent forms of protest.[134]

This was highlighted by the Salt March to Dandi from 12 March to 6 April, where, together with 78 volunteers, he marched 388 kilometres (241 mi) from Ahmedabad to Dandi, Gujarat to make salt himself, with the declared intention of breaking the salt laws. The march took 25 days to cover 240 miles with Gandhi speaking to often huge crowds along the way. Thousands of Indians joined him in Dandi. On 5 May he was interned under a regulation dating from 1827 in anticipation of a protest that he had planned. The protest at Dharasana salt works on 21 May went ahead without him see. A horrified American journalist, Webb Miller, described the British response thus:

In complete silence the Gandhi men drew up and halted a hundred yards from the stockade. A picked column advanced from the crowd, waded the ditches and approached the barbed wire stockade... at a word of command, scores of native policemen rushed upon the advancing marchers and rained blows on their heads with their steel-shot lathis [long bamboo sticks]. Not one of the marchers even raised an arm to fend off blows. They went down like ninepins. From where I stood I heard the sickening whack of the clubs on unprotected skulls... Those struck down fell sprawling, unconscious or writhing with fractured skulls or broken shoulders.[135]

This went on for hours until some 300 or more protesters had been beaten, many seriously injured and two killed. At no time did they offer any resistance.

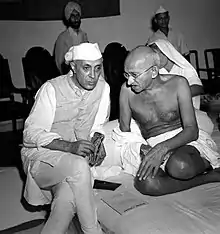

This campaign was one of his most successful at upsetting British hold on India; Britain responded by imprisoning over 60,000 people.[136] Congress estimates, however, put the figure at 90,000. Among them was one of Gandhi's lieutenants, Jawaharlal Nehru.

According to Sarma, Gandhi recruited women to participate in the salt tax campaigns and the boycott of foreign products, which gave many women a new self-confidence and dignity in the mainstream of Indian public life.[137] However, other scholars such as Marilyn French state that Gandhi barred women from joining his civil disobedience movement because he feared he would be accused of using women as a political shield.[138] When women insisted on joining the movement and participating in public demonstrations, Gandhi asked the volunteers to get permissions of their guardians and only those women who can arrange child-care should join him.[139] Regardless of Gandhi's apprehensions and views, Indian women joined the Salt March by the thousands to defy the British salt taxes and monopoly on salt mining. After Gandhi's arrest, the women marched and picketed shops on their own, accepting violence and verbal abuse from British authorities for the cause in the manner Gandhi inspired.[138]

Gandhi as folk hero

Indian Congress in the 1920s appealed to Andhra Pradesh peasants by creating Telugu language plays that combined Indian mythology and legends, linked them to Gandhi's ideas, and portrayed Gandhi as a messiah, a reincarnation of ancient and medieval Indian nationalist leaders and saints. The plays built support among peasants steeped in traditional Hindu culture, according to Murali, and this effort made Gandhi a folk hero in Telugu speaking villages, a sacred messiah-like figure.[140]

According to Dennis Dalton, it was Gandhi's ideas that were responsible for his wide following. Gandhi criticised Western civilisation as one driven by "brute force and immorality", contrasting it with his categorisation of Indian civilisation as one driven by "soul force and morality".[141] Gandhi captured the imagination of the people of his heritage with his ideas about winning "hate with love". These ideas are evidenced in his pamphlets from the 1890s, in South Africa, where too he was popular among the Indian indentured workers. After he returned to India, people flocked to him because he reflected their values.[141]

Gandhi also campaigned hard going from one rural corner of the Indian subcontinent to another. He used terminology and phrases such as Rama-rajya from Ramayana, Prahlada as a paradigmatic icon, and such cultural symbols as another facet of swaraj and satyagraha.[142] During his lifetime, these ideas sounded strange outside India, but they readily and deeply resonated with the culture and historic values of his people.[141][143]

Negotiations

The government, represented by Lord Irwin, decided to negotiate with Gandhi. The Gandhi–Irwin Pact was signed in March 1931. The British Government agreed to free all political prisoners, in return for the suspension of the civil disobedience movement. According to the pact, Gandhi was invited to attend the Round Table Conference in London for discussions and as the sole representative of the Indian National Congress. The conference was a disappointment to Gandhi and the nationalists. Gandhi expected to discuss India's independence, while the British side focused on the Indian princes and Indian minorities rather than on a transfer of power. Lord Irwin's successor, Lord Willingdon, took a hard line against India as an independent nation, began a new campaign of controlling and subduing the nationalist movement. Gandhi was again arrested, and the government tried and failed to negate his influence by completely isolating him from his followers.[144]

In Britain, Winston Churchill, a prominent Conservative politician who was then out of office but later became its prime minister, became a vigorous and articulate critic of Gandhi and opponent of his long-term plans. Churchill often ridiculed Gandhi, saying in a widely reported 1931 speech:

It is alarming and also nauseating to see Mr Gandhi, a seditious Middle Temple lawyer, now posing as a fakir of a type well known in the East, striding half-naked up the steps of the Vice-regal palace....to parley on equal terms with the representative of the King-Emperor.[145]

Churchill's bitterness against Gandhi grew in the 1930s. He called Gandhi as the one who was "seditious in aim" whose evil genius and multiform menace was attacking the British empire. Churchill called him a dictator, a "Hindu Mussolini", fomenting a race war, trying to replace the Raj with Brahmin cronies, playing on the ignorance of Indian masses, all for selfish gain.[146] Churchill attempted to isolate Gandhi, and his criticism of Gandhi was widely covered by European and American press. It gained Churchill sympathetic support, but it also increased support for Gandhi among Europeans. The developments heightened Churchill's anxiety that the "British themselves would give up out of pacifism and misplaced conscience".[146]

Round Table Conferences

During the discussions between Gandhi and the British government over 1931–32 at the Round Table Conferences, Gandhi, now aged about 62, sought constitutional reforms as a preparation to the end of colonial British rule, and begin the self-rule by Indians.[147] The British side sought reforms that would keep the Indian subcontinent as a colony. The British negotiators proposed constitutional reforms on a British Dominion model that established separate electorates based on religious and social divisions. The British questioned the Congress party and Gandhi's authority to speak for all of India.[148] They invited Indian religious leaders, such as Muslims and Sikhs, to press their demands along religious lines, as well as B. R. Ambedkar as the representative leader of the untouchables.[147] Gandhi vehemently opposed a constitution that enshrined rights or representations based on communal divisions, because he feared that it would not bring people together but divide them, perpetuate their status, and divert the attention from India's struggle to end the colonial rule.[149][150]

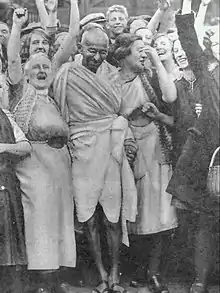

The Second Round Table conference was the only time he left India between 1914 and his death in 1948. He declined the government's offer of accommodation in an expensive West End hotel, preferring to stay in the East End, to live among working-class people, as he did in India.[151] He based himself in a small cell-bedroom at Kingsley Hall for the three-month duration of his stay and was enthusiastically received by East Enders.[152] During this time he renewed his links with the British vegetarian movement.

After Gandhi returned from the Second Round Table conference, he started a new satyagraha. He was arrested and imprisoned at the Yerwada Jail, Pune. While he was in prison, the British government enacted a new law that granted untouchables a separate electorate. It came to be known as the Communal Award.[153] In protest, Gandhi started a fast-unto-death, while he was held in prison.[154] The resulting public outcry forced the government, in consultations with Ambedkar, to replace the Communal Award with a compromise Poona Pact.[155][156]

Congress politics

In 1934 Gandhi resigned from Congress party membership. He did not disagree with the party's position but felt that if he resigned, his popularity with Indians would cease to stifle the party's membership, which actually varied, including communists, socialists, trade unionists, students, religious conservatives, and those with pro-business convictions, and that these various voices would get a chance to make themselves heard. Gandhi also wanted to avoid being a target for Raj propaganda by leading a party that had temporarily accepted political accommodation with the Raj.[157]

Gandhi returned to active politics again in 1936, with the Nehru presidency and the Lucknow session of the Congress. Although Gandhi wanted a total focus on the task of winning independence and not speculation about India's future, he did not restrain the Congress from adopting socialism as its goal. Gandhi had a clash with Subhas Chandra Bose, who had been elected president in 1938, and who had previously expressed a lack of faith in nonviolence as a means of protest.[158] Despite Gandhi's opposition, Bose won a second term as Congress President, against Gandhi's nominee, Dr. Pattabhi Sitaramayya; but left the Congress when the All-India leaders resigned en masse in protest of his abandonment of the principles introduced by Gandhi.[159][160] Gandhi declared that Sitaramayya's defeat was his defeat.[161]

World War II and Quit India movement

Gandhi opposed providing any help to the British war effort and he campaigned against any Indian participation in World War II.[162] Gandhi's campaign did not enjoy the support of the Indian population nor of many Indian leaders, such as Sardar Patel and Rajendra Prasad, and as such failed.[162] Despite his efforts, over 2.5 million Indians volunteered and joined the British military to fight on various fronts of the Allied Forces.[162]

Gandhi's opposition to the Indian participation in World War II was motivated by his belief that India could not be party to a war ostensibly being fought for democratic freedom while that freedom was denied to India itself.[163] He also condemned Nazism and Fascism, a view which won endorsement of other Indian leaders. As the war progressed, Gandhi intensified his demand for independence, calling for the British to Quit India in a 1942 speech in Mumbai.[164] This was Gandhi's and the Congress Party's most definitive revolt aimed at securing the British exit from India.[165] The British government responded quickly to the Quit India speech, and within hours after Gandhi's speech arrested Gandhi and all the members of the Congress Working Committee.[166] His countrymen retaliated the arrests by damaging or burning down hundreds of government owned railway stations, police stations, and cutting down telegraph wires.[167]

In 1942, Gandhi now nearing age 73, urged his people to completely stop co-operating with the imperial government. In this effort, he urged that they neither kill nor injure British people, but be willing to suffer and die if violence is initiated by the British officials.[164] He clarified that the movement would not be stopped because of any individual acts of violence, saying that the "ordered anarchy" of "the present system of administration" was "worse than real anarchy."[168][169] He urged Indians to Karo ya maro ("Do or die") in the cause of their rights and freedoms.[164][170]

Gandhi's arrest lasted two years, as he was held in the Aga Khan Palace in Pune. During this period, his long time secretary Mahadev Desai died of a heart attack, his wife Kasturba died after 18 months' imprisonment on 22 February 1944; and Gandhi suffered a severe malaria attack.[167] While in jail, he agreed to an interview with Stuart Gelder, a British journalist. Gelder then composed and released an interview summary, cabled it to the mainstream press, that announced sudden concessions Gandhi was willing to make, comments that shocked his countrymen, the Congress workers and even Gandhi. The latter two claimed that it distorted what Gandhi actually said on a range of topics and falsely repudiated the Quit India movement.[167]

Gandhi was released before the end of the war on 6 May 1944 because of his failing health and necessary surgery; the Raj did not want him to die in prison and enrage the nation. He came out of detention to an altered political scene – the Muslim League for example, which a few years earlier had appeared marginal, "now occupied the centre of the political stage"[171] and the topic of Muhammad Ali Jinnah's campaign for Pakistan was a major talking point. Gandhi and Jinnah had extensive correspondence and the two men met several times over a period of two weeks in September 1944 at Jinnah's house in Bombay, where Gandhi insisted on a united religiously plural and independent India which included Muslims and non-Muslims of the Indian subcontinent coexisting. Jinnah rejected this proposal and insisted instead for partitioning the subcontinent on religious lines to create a separate Muslim India (later Pakistan).[10][172] These discussions continued through 1947.[173]

While the leaders of Congress languished in jail, the other parties supported the war and gained organisational strength. Underground publications flailed at the ruthless suppression of Congress, but it had little control over events.[174] At the end of the war, the British gave clear indications that power would be transferred to Indian hands. At this point Gandhi called off the struggle, and around 100,000 political prisoners were released, including the Congress's leadership.[175]

Partition and independence

Gandhi opposed the partition of the Indian subcontinent along religious lines.[176] The Indian National Congress and Gandhi called for the British to Quit India. However, the Muslim League demanded "Divide and Quit India".[177][178] Gandhi suggested an agreement which required the Congress and the Muslim League to co-operate and attain independence under a provisional government, thereafter, the question of partition could be resolved by a plebiscite in the districts with a Muslim majority.[179]

Jinnah rejected Gandhi's proposal and called for Direct Action Day, on 16 August 1946, to press Muslims to publicly gather in cities and support his proposal for the partition of the Indian subcontinent into a Muslim state and non-Muslim state. Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, the Muslim League Chief Minister of Bengal – now Bangladesh and West Bengal, gave Calcutta's police special holiday to celebrate the Direct Action Day.[180] The Direct Action Day triggered a mass murder of Calcutta Hindus and the torching of their property, and holidaying police were missing to contain or stop the conflict.[181] The British government did not order its army to move in to contain the violence.[180] The violence on Direct Action Day led to retaliatory violence against Muslims across India. Thousands of Hindus and Muslims were murdered, and tens of thousands were injured in the cycle of violence in the days that followed.[182] Gandhi visited the most riot-prone areas to appeal a stop to the massacres.[181]

.jpg.webp)

Archibald Wavell, the Viceroy and Governor-General of British India for three years through February 1947, had worked with Gandhi and Jinnah to find a common ground, before and after accepting Indian independence in principle. Wavell condemned Gandhi's character and motives as well as his ideas. Wavell accused Gandhi of harbouring the single minded idea to "overthrow British rule and influence and to establish a Hindu raj", and called Gandhi a "malignant, malevolent, exceedingly shrewd" politician.[183] Wavell feared a civil war on the Indian subcontinent, and doubted Gandhi would be able to stop it.[183]

The British reluctantly agreed to grant independence to the people of the Indian subcontinent, but accepted Jinnah's proposal of partitioning the land into Pakistan and India. Gandhi was involved in the final negotiations, but Stanley Wolpert states the "plan to carve up British India was never approved of or accepted by Gandhi".[184]

The partition was controversial and violently disputed. More than half a million were killed in religious riots as 10 million to 12 million non-Muslims (Hindus and Sikhs mostly) migrated from Pakistan into India, and Muslims migrated from India into Pakistan, across the newly created borders of India, West Pakistan and East Pakistan.[185]

Gandhi spent the day of independence not celebrating the end of the British rule but appealing for peace among his countrymen by fasting and spinning in Calcutta on 15 August 1947. The partition had gripped the Indian subcontinent with religious violence and the streets were filled with corpses.[186] Some writers credit Gandhi's fasting and protests for stopping the religious riots and communal violence.[183]

Death

At 5:17 pm on 30 January 1948, Gandhi was with his grandnieces in the garden of Birla House (now Gandhi Smriti), on his way to address a prayer meeting, when Nathuram Godse, a Hindu nationalist, fired three bullets into his chest from a pistol at close range. According to some accounts, Gandhi died instantly.[187][188] In other accounts, such as one prepared by an eyewitness journalist, Gandhi was carried into the Birla House, into a bedroom. There he died about 30 minutes later as one of Gandhi's family members read verses from Hindu scriptures.[189]

Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru addressed his countrymen over the All-India Radio saying:[190]

Friends and comrades, the light has gone out of our lives, and there is darkness everywhere, and I do not quite know what to tell you or how to say it. Our beloved leader, Bapu as we called him, the father of the nation, is no more. Perhaps I am wrong to say that; nevertheless, we will not see him again, as we have seen him for these many years, we will not run to him for advice or seek solace from him, and that is a terrible blow, not only for me, but for millions and millions in this country.[191]

Godse, a Hindu nationalist with links to the extremist Hindu Mahasabha,[192] made no attempt to escape; several other conspirators were soon arrested as well.[193][194] They were tried in court at Delhi's Red Fort. At his trial, Godse did not deny the charges nor express any remorse. According to Claude Markovits, a French historian noted for his studies of colonial India, Godse stated that he killed Gandhi because of his complacence towards Muslims, holding Gandhi responsible for the frenzy of violence and sufferings during the subcontinent's partition into Pakistan and India. Godse accused Gandhi of subjectivism and of acting as if only he had a monopoly of the truth. Godse was found guilty and executed in 1949.[195][196]

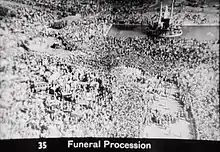

Gandhi's death was mourned nationwide. Over a million people joined the five-mile-long funeral procession that took over five hours to reach Raj Ghat from Birla house, where he was assassinated, and another million watched the procession pass by.[197] Gandhi's body was transported on a weapons carrier, whose chassis was dismantled overnight to allow a high-floor to be installed so that people could catch a glimpse of his body. The engine of the vehicle was not used; instead four drag-ropes held by 50 people each pulled the vehicle.[198] All Indian-owned establishments in London remained closed in mourning as thousands of people from all faiths and denominations and Indians from all over Britain converged at India House in London.[199]

Gandhi's assassination dramatically changed the political landscape. Nehru became his political heir. According to Markovits, while Gandhi was alive, Pakistan's declaration that it was a "Muslim state" had led Indian groups to demand that it be declared a "Hindu state".[195] Nehru used Gandhi's martyrdom as a political weapon to silence all advocates of Hindu nationalism as well as his political challengers. He linked Gandhi's assassination to politics of hatred and ill-will.[195]

According to Guha, Nehru and his Congress colleagues called on Indians to honour Gandhi's memory and even more his ideals.[200][201] Nehru used the assassination to consolidate the authority of the new Indian state. Gandhi's death helped marshal support for the new government and legitimise the Congress Party's control, leveraged by the massive outpouring of Hindu expressions of grief for a man who had inspired them for decades. The government suppressed the RSS, the Muslim National Guards, and the Khaksars, with some 200,000 arrests.[202]

For years after the assassination, states Markovits, "Gandhi's shadow loomed large over the political life of the new Indian Republic". The government quelled any opposition to its economic and social policies, despite these being contrary to Gandhi's ideas, by reconstructing Gandhi's image and ideals.[203]

Funeral and memorials

Gandhi was cremated in accordance with Hindu tradition. Gandhi's ashes were poured into urns which were sent across India for memorial services.[205] Most of the ashes were immersed at the Sangam at Allahabad on 12 February 1948, but some were secretly taken away. In 1997, Tushar Gandhi immersed the contents of one urn, found in a bank vault and reclaimed through the courts, at the Sangam at Allahabad.[206][207] Some of Gandhi's ashes were scattered at the source of the Nile River near Jinja, Uganda, and a memorial plaque marks the event. On 30 January 2008, the contents of another urn were immersed at Girgaum Chowpatty. Another urn is at the palace of the Aga Khan in Pune (where Gandhi was held as a political prisoner from 1942 to 1944[208][209]) and another in the Self-Realization Fellowship Lake Shrine in Los Angeles.[206][210]

The Birla House site where Gandhi was assassinated is now a memorial called Gandhi Smriti. The place near Yamuna river where he was cremated is the Rāj Ghāt memorial in New Delhi.[211] A black marble platform, it bears the epigraph "Hē Rāma" (Devanagari: हे ! राम or, Hey Raam). These are widely believed to be Gandhi's last words after he was shot, though the veracity of this statement has been questioned.[212]

Principles, practices, and beliefs

Gandhi's statements, letters and life have attracted much political and scholarly analysis of his principles, practices and beliefs, including what influenced him. Some writers present him as a paragon of ethical living and pacifism, while others present him as a more complex, contradictory and evolving character influenced by his culture and circumstances.[213][214]

Influences

Gandhi grew up in a Hindu and Jain religious atmosphere in his native Gujarat, which were his primary influences, but he was also influenced by his personal reflections and literature of Hindu Bhakti saints, Advaita Vedanta, Islam, Buddhism, Christianity, and thinkers such as Tolstoy, Ruskin and Thoreau.[215][216] At age 57 he declared himself to be Advaitist Hindu in his religious persuasion, but added that he supported Dvaitist viewpoints and religious pluralism.[217][218][219]

Gandhi was influenced by his devout Vaishnava Hindu mother, the regional Hindu temples and saint tradition which co-existed with Jain tradition in Gujarat.[215][220] Historian R.B. Cribb states that Gandhi's thought evolved over time, with his early ideas becoming the core or scaffolding for his mature philosophy. He committed himself early to truthfulness, temperance, chastity, and vegetarianism.[221]

Gandhi's London lifestyle incorporated the values he had grown up with. When he returned to India in 1891, his outlook was parochial and he could not make a living as a lawyer. This challenged his belief that practicality and morality necessarily coincided. By moving in 1893 to South Africa he found a solution to this problem and developed the central concepts of his mature philosophy.[222]

According to Bhikhu Parekh, three books that influenced Gandhi most in South Africa were William Salter's Ethical Religion (1889); Henry David Thoreau's On the Duty of Civil Disobedience (1849); and Leo Tolstoy's The Kingdom of God Is Within You (1894). The art critic and critic of political economy John Ruskin inspired his decision to live an austere life on a commune, at first on the Phoenix Farm in Natal and then on the Tolstoy Farm just outside Johannesburg, South Africa.[66] The most profound influence on Gandhi were those from Hinduism, Christianity and Jainism, states Parekh, with his thoughts "in harmony with the classical Indian traditions, specially the Advaita or monistic tradition".[223]

According to Indira Carr and others, Gandhi was influenced by Vaishnavism, Jainism and Advaita Vedanta.[224][225] Balkrishna Gokhale states that Gandhi was influenced by Hinduism and Jainism, and his studies of Sermon on the Mount of Christianity, Ruskin and Tolstoy.[226]

Additional theories of possible influences on Gandhi have been proposed. For example, in 1935, N. A. Toothi stated that Gandhi was influenced by the reforms and teachings of the Swaminarayan tradition of Hinduism. According to Raymond Williams, Toothi may have overlooked the influence of the Jain community, and adds close parallels do exist in programs of social reform in the Swaminarayan tradition and those of Gandhi, based on "nonviolence, truth-telling, cleanliness, temperance and upliftment of the masses."[227][228] Historian Howard states the culture of Gujarat influenced Gandhi and his methods.[229]

Leo Tolstoy

Along with the book mentioned above, in 1908 Leo Tolstoy wrote A Letter to a Hindu, which said that only by using love as a weapon through passive resistance could the Indian people overthrow colonial rule. In 1909, Gandhi wrote to Tolstoy seeking advice and permission to republish A Letter to a Hindu in Gujarati. Tolstoy responded and the two continued a correspondence until Tolstoy's death in 1910 (Tolstoy's last letter was to Gandhi).[230] The letters concern practical and theological applications of nonviolence.[231] Gandhi saw himself a disciple of Tolstoy, for they agreed regarding opposition to state authority and colonialism; both hated violence and preached non-resistance. However, they differed sharply on political strategy. Gandhi called for political involvement; he was a nationalist and was prepared to use nonviolent force. He was also willing to compromise.[232] It was at Tolstoy Farm where Gandhi and Hermann Kallenbach systematically trained their disciples in the philosophy of nonviolence.[233]

Shrimad Rajchandra

Gandhi credited Shrimad Rajchandra, a poet and Jain philosopher, as his influential counsellor. In Modern Review, June 1930, Gandhi wrote about their first encounter in 1891 at Dr. P.J. Mehta's residence in Bombay. He was introduced to Shrimad by Dr. Pranjivan Mehta.[234] Gandhi exchanged letters with Rajchandra when he was in South Africa, referring to him as Kavi (literally, "poet"). In 1930, Gandhi wrote, "Such was the man who captivated my heart in religious matters as no other man ever has till now."[235] "I have said elsewhere that in moulding my inner life Tolstoy and Ruskin vied with Kavi. But Kavi's influence was undoubtedly deeper if only because I had come in closest personal touch with him."[236]

Gandhi, in his autobiography, called Rajchandra his "guide and helper" and his "refuge [...] in moments of spiritual crisis". He had advised Gandhi to be patient and to study Hinduism deeply.[237][238]

Religious texts

During his stay in South Africa, along with scriptures and philosophical texts of Hinduism and other Indian religions, Gandhi read translated texts of Christianity such as the Bible, and Islam such as the Quran.[239] A Quaker mission in South Africa attempted to convert him to Christianity. Gandhi joined them in their prayers and debated Christian theology with them, but refused conversion stating he did not accept the theology therein or that Christ was the only son of God.[239][240][241]

His comparative studies of religions and interaction with scholars, led him to respect all religions as well as become concerned about imperfections in all of them and frequent misinterpretations.[239] Gandhi grew fond of Hinduism, and referred to the Bhagavad Gita as his spiritual dictionary and greatest single influence on his life.[239][242][243] Later, Gandhi translated the Gita into Gujarati in 1930.[244]

Sufism

Gandhi was acquainted with Sufi Islam's Chishti Order during his stay in South Africa. He attended Khanqah gatherings there at Riverside. According to Margaret Chatterjee, Gandhi as a Vaishnava Hindu shared values such as humility, devotion and brotherhood for the poor that is also found in Sufism.[245][246] Winston Churchill also compared Gandhi to a Sufi fakir.[145]

Support for wars

Gandhi participated in forming the Indian Ambulance Corps in the South African war against the Boers, on the British side in 1899.[247] Both the Dutch settlers called Boers and the imperial British at that time discriminated against the coloured races they considered as inferior, and Gandhi later wrote about his conflicted beliefs during the Boer war. He stated that "when the war was declared, my personal sympathies were all with the Boers, but my loyalty to the British rule drove me to participation with the British in that war. I felt that, if I demanded rights as a British citizen, it was also my duty, as such to participate in the defence of the British Empire, so I collected together as many comrades as possible, and with very great difficulty got their services accepted as an ambulance corps."[248]

During World War I (1914–1918), nearing the age of 50, Gandhi supported the British and its allied forces by recruiting Indians to join the British army, expanding the Indian contingent from about 100,000 to over 1.1 million.[105][247] He encouraged Indian people to fight on one side of the war in Europe and Africa at the cost of their lives.[247] Pacifists criticised and questioned Gandhi, who defended these practices by stating, according to Sankar Ghose, "it would be madness for me to sever my connection with the society to which I belong".[247] According to Keith Robbins, the recruitment effort was in part motivated by the British promise to reciprocate the help with swaraj (self-government) to Indians after the end of World War I.[104] After the war, the British government offered minor reforms instead, which disappointed Gandhi.[105] He launched his satyagraha movement in 1919. In parallel, Gandhi's fellowmen became sceptical of his pacifist ideas and were inspired by the ideas of nationalism and anti-imperialism.[249]

In a 1920 essay, after the World War I, Gandhi wrote, "where there is only a choice between cowardice and violence, I would advise violence." Rahul Sagar interprets Gandhi's efforts to recruit for the British military during the War, as Gandhi's belief that, at that time, it would demonstrate that Indians were willing to fight. Further, it would also show the British that his fellow Indians were "their subjects by choice rather than out of cowardice." In 1922, Gandhi wrote that abstinence from violence is effective and true forgiveness only when one has the power to punish, not when one decides not to do anything because one is helpless.[250]

After World War II engulfed Britain, Gandhi actively campaigned to oppose any help to the British war effort and any Indian participation in the war. According to Arthur Herman, Gandhi believed that his campaign would strike a blow to imperialism.[162] Gandhi's position was not supported by many Indian leaders, and his campaign against the British war effort was a failure. The Hindu leader, Tej Bahadur Sapru, declared in 1941, states Herman, "A good many Congress leaders are fed up with the barren program of the Mahatma".[162] Over 2.5 million Indians ignored Gandhi, volunteered and joined on the British side. They fought and died as a part of the Allied forces in Europe, North Africa and various fronts of the World War II.[162]

Truth and Satyagraha

Gandhi dedicated his life to discovering and pursuing truth, or Satya, and called his movement satyagraha, which means "appeal to, insistence on, or reliance on the Truth".[251] The first formulation of the satyagraha as a political movement and principle occurred in 1920, which he tabled as "Resolution on Non-cooperation" in September that year before a session of the Indian Congress. It was the satyagraha formulation and step, states Dennis Dalton, that deeply resonated with beliefs and culture of his people, embedded him into the popular consciousness, transforming him quickly into Mahatma.[252]

Gandhi based Satyagraha on the Vedantic ideal of self-realisation, ahimsa (nonviolence), vegetarianism, and universal love. William Borman states that the key to his satyagraha is rooted in the Hindu Upanishadic texts.[253] According to Indira Carr, Gandhi's ideas on ahimsa and satyagraha were founded on the philosophical foundations of Advaita Vedanta.[254] I. Bruce Watson states that some of these ideas are found not only in traditions within Hinduism, but also in Jainism or Buddhism, particularly those about non-violence, vegetarianism and universal love, but Gandhi's synthesis was to politicise these ideas.[255] Gandhi's concept of satya as a civil movement, states Glyn Richards, are best understood in the context of the Hindu terminology of Dharma and Ṛta.[256]

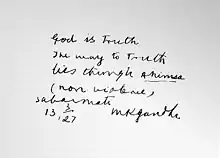

Gandhi stated that the most important battle to fight was overcoming his own demons, fears, and insecurities. Gandhi summarised his beliefs first when he said "God is Truth". He would later change this statement to "Truth is God". Thus, satya (truth) in Gandhi's philosophy is "God".[257] Gandhi, states Richards, described the term "God" not as a separate power, but as the Being (Brahman, Atman) of the Advaita Vedanta tradition, a nondual universal that pervades in all things, in each person and all life.[256] According to Nicholas Gier, this to Gandhi meant the unity of God and humans, that all beings have the same one soul and therefore equality, that atman exists and is same as everything in the universe, ahimsa (non-violence) is the very nature of this atman.[258]

The essence of Satyagraha is "soul force" as a political means, refusing to use brute force against the oppressor, seeking to eliminate antagonisms between the oppressor and the oppressed, aiming to transform or "purify" the oppressor. It is not inaction but determined passive resistance and non-co-operation where, states Arthur Herman, "love conquers hate".[261] A euphemism sometimes used for Satyagraha is that it is a "silent force" or a "soul force" (a term also used by Martin Luther King Jr. during his "I Have a Dream" speech). It arms the individual with moral power rather than physical power. Satyagraha is also termed a "universal force", as it essentially "makes no distinction between kinsmen and strangers, young and old, man and woman, friend and foe."[262]

Gandhi wrote: "There must be no impatience, no barbarity, no insolence, no undue pressure. If we want to cultivate a true spirit of democracy, we cannot afford to be intolerant. Intolerance betrays want of faith in one's cause."[263] Civil disobedience and non-co-operation as practised under Satyagraha are based on the "law of suffering",[264] a doctrine that the endurance of suffering is a means to an end. This end usually implies a moral upliftment or progress of an individual or society. Therefore, non-co-operation in Satyagraha is in fact a means to secure the co-operation of the opponent consistently with truth and justice.[265]

While Gandhi's idea of satyagraha as a political means attracted a widespread following among Indians, the support was not universal. For example, Muslim leaders such as Jinnah opposed the satyagraha idea, accused Gandhi to be reviving Hinduism through political activism, and began effort to counter Gandhi with Muslim nationalism and a demand for Muslim homeland.[266][267][268] The untouchability leader Ambedkar, in June 1945, after his decision to convert to Buddhism and a key architect of the Constitution of modern India, dismissed Gandhi's ideas as loved by "blind Hindu devotees", primitive, influenced by spurious brew of Tolstoy and Ruskin, and "there is always some simpleton to preach them".[269][270] Winston Churchill caricatured Gandhi as a "cunning huckster" seeking selfish gain, an "aspiring dictator", and an "atavistic spokesman of a pagan Hinduism". Churchill stated that the civil disobedience movement spectacle of Gandhi only increased "the danger to which white people there [British India] are exposed".[271]

Nonviolence

Although Gandhi was not the originator of the principle of nonviolence, he was the first to apply it in the political field on a large scale.[272] The concept of nonviolence (ahimsa) has a long history in Indian religious thought, and is considered the highest dharma (ethical value virtue), a precept to be observed towards all living beings (sarvbhuta), at all times (sarvada), in all respects (sarvatha), in action, words and thought.[273] Gandhi explains his philosophy and ideas about ahimsa as a political means in his autobiography The Story of My Experiments with Truth.[274][275][276]

Gandhi was criticised for refusing to protest the hanging of Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev, Udham Singh and Rajguru.[277][278] He was accused of accepting a deal with the King's representative Irwin that released civil disobedience leaders from prison and accepted the death sentence against the highly popular revolutionary Bhagat Singh, who at his trial had replied, "Revolution is the inalienable right of mankind".[132] However Congressmen, who were votaries of non-violence, defended Bhagat Singh and other revolutionary nationalists being tried in Lahore.[279]

Gandhi's views came under heavy criticism in Britain when it was under attack from Nazi Germany, and later when the Holocaust was revealed. He told the British people in 1940, "I would like you to lay down the arms you have as being useless for saving you or humanity. You will invite Herr Hitler and Signor Mussolini to take what they want of the countries you call your possessions... If these gentlemen choose to occupy your homes, you will vacate them. If they do not give you free passage out, you will allow yourselves, man, woman, and child, to be slaughtered, but you will refuse to owe allegiance to them."[280] George Orwell remarked that Gandhi's methods confronted "an old-fashioned and rather shaky despotism which treated him in a fairly chivalrous way", not a totalitarian power, "where political opponents simply disappear."[281]

In a post-war interview in 1946, he said, "Hitler killed five million Jews. It is the greatest crime of our time. But the Jews should have offered themselves to the butcher's knife. They should have thrown themselves into the sea from cliffs... It would have aroused the world and the people of Germany... As it is they succumbed anyway in their millions."[282] Gandhi believed this act of "collective suicide", in response to the Holocaust, "would have been heroism".[283]