Hook (film)

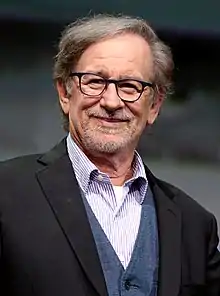

Hook is a 1991 American adventure film directed by Steven Spielberg and written by James V. Hart and Malia Scotch Marmo. It stars Robin Williams as Peter Banning / Peter Pan, Dustin Hoffman as Captain Hook, Julia Roberts as Tinker Bell, Bob Hoskins as Mr. Smee, and Maggie Smith as Granny Wendy. It acts as a sequel of sorts to J. M. Barrie's 1911 novel Peter and Wendy focusing on an adult Peter Pan who has forgotten all about his childhood. In his new life, he is known as Peter Banning, a successful but unimaginative and workaholic lawyer with a wife (Wendy's granddaughter) and two children. However, when Captain Hook, the enemy of his past, kidnaps his children, he returns to Neverland to save them. Along the journey, he reclaims the memories of his past and becomes a better person.

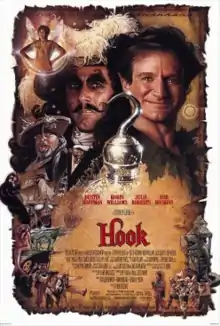

| Hook | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster by Drew Struzan | |

| Directed by | Steven Spielberg |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by |

|

| Based on | Peter and Wendy by J. M. Barrie |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Dean Cundey |

| Edited by | Michael Kahn |

| Music by | John Williams |

Production company | Amblin Entertainment |

| Distributed by | TriStar Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 142 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $70 million[2] |

| Box office | $300.9 million |

Spielberg began developing Hook in the early 1980s with Walt Disney Productions and Paramount Pictures, which would have followed the Peter Pan storyline seen in the 1924 silent film and 1953 animated Disney film. It entered pre-production in 1985, but Spielberg abandoned the project. Hart developed the script with director Nick Castle and TriStar Pictures before Spielberg decided to direct in 1989. It was shot almost entirely on sound stages at Sony Pictures Studios in Culver City, California.

Released on December 11, 1991, Hook received mixed reviews from critics, who praised the performances (particularly those of Robin Williams and Hoffman), John Williams' musical score, and production values, but criticized the screenplay and tone. Although it was a commercial success, its box office take was lower than expected. Despite its five nominations at the 64th Academy Awards, Spielberg came to be disappointed with Hook. Nevertheless, it has gained a strong cult following since its release, and spawned merchandise, including video games, action figures, and comic book adaptations.

Plot

Successful San Francisco corporate lawyer Peter Banning is a workaholic, straining his relationship with his wife Moira and their children Jack and Maggie. After promising to attend at least one of Jack's baseball games, but missing the last game of the season, Peter flies with his disappointed family to London to visit Moira's grandmother, Wendy Darling. In London, Peter, Moira and Wendy attend a charity dinner in Wendy's honor at the Great Ormond Street Hospital, leaving the children with Wendy's old friend Tootles and housekeeper Liza. After returning, they find the house burglarized and the children missing, along with a ransom note signed by Captain James Hook. Peter involves the authorities, but they are unable to help, and Wendy insists that only he can save Jack and Maggie, as he is really Peter Pan; Peter refuses to believe her.

Later, in the nursery, he encounters Tinker Bell, who brings him to Neverland. She drops Peter into Hook's pirate haven, where he reveals himself to Smee and Hook. Surprised to see how weak and old Peter has become, Hook challenges him to fly and rescue his children, preparing to execute him when he fails. Tinker Bell intervenes and persuades Hook to release Peter instead, promising to train him for battle over the next three days and give him the fight he desires. Peter is then taken to the hideout of the Lost Boys, now led by Rufio. The boys mock Peter, but eventually recognize and train him, encouraging him to use the power of imagination to help restore his memory and abilities. One boy, Thud Butt, gives Peter an old bag of marbles belonging to former Lost Boy Tootles.

Meanwhile, Hook laments that he will not have true revenge on Peter, until Smee suggests they manipulate the Banning children into switching sides. This plan fails with Maggie, but Jack is swayed due to Peter's repeated broken promises. Dismayed to see Jack treating Hook as a father figure, Peter returns to the Lost Boys' camp with renewed determination. After seeing his shadow move independently, Peter follows it and discovers the original treehouse where Wendy and her brothers once stayed. Inside, Tinker Bell helps Peter remember how he was lost as an infant in the early 1900s, brought by her to Neverland, had many adventures, and first met the Darlings. He also recalls frequently visiting Wendy after the Darlings returned to London, until Wendy grew too old to go back. Although heartbroken, Peter then fell in love with Wendy's granddaughter Moira and chose to stay, due to his desire to become a father. He became adopted by the Bannings, but at the cost of his memories.

Recalling Jack's birth is the strong, happy thought that restores Peter's ability to fly, bringing him back as Peter Pan. Rufio turns his sword over to Peter in reverence and the Lost Boys celebrate. That night, Tinker Bell professes her love for Peter with a kiss. However, Peter still chooses his family and professes his love for Moira. Although heartbroken by his rejection, Tinker Bell accepts this and encourages him to go save his children.

The next day, Peter and the Lost Boys fight Hook and his pirates while Jack watches. Hook's crew eventually surrenders, but Rufio duels Hook and is fatally wounded. With his dying breath, Rufio wishes he could have had a father like Peter. Jack comes to his senses and reconciles with his father. In the ensuing fight, Peter defeats Hook, who is devoured by the reanimated corpse of the taxidermied Crocodile. Tinker Bell takes Jack and Maggie back to London, and Peter appoints Thud Butt as his successor.

Peter awakens in Kensington Gardens. Tinker Bell appears and bids a tearful farewell to Peter before departing. Reuniting with his family at Wendy's house, Peter decides to devote more time to them. He also returns Tootles' bag of marbles; Tootles joyfully sprinkles himself with pixie dust from it and flies away. As Peter and his family watch Tootles return to Neverland, Wendy remarks that their adventures are truly over; Peter counters that "to live would be an awfully big adventure".

Cast

- Robin Williams as Peter Banning / Peter Pan

- Ryan Francis as preteen Peter Pan

- Max Hoffman as young Peter Pan

- Matthew Van Ginkel as baby Peter Pan

- Dustin Hoffman as Captain Hook

- Julia Roberts as Tinker Bell

- Lisa Wilhoit as Tinker Bell in a flashback in which Peter is a baby

- Bob Hoskins as Smee / Sweeper in Kensington Gardens

- Maggie Smith as Granny Wendy

- Gwyneth Paltrow as teenage Wendy Darling

- Charlie Korsmo as Jack Banning, Peter and Moira's son

- Amber Scott as Maggie Banning, Peter and Moira's daughter

- Caroline Goodall as Moira Banning, Peter's wife and Jack and Maggie's mother

- Dante Basco as Rufio

- Jasen Fisher as Ace

- Raushan Hammond as Thud Butt

- Isaiah Robinson as Pockets

- James Madio as Don't Ask

- Arthur Malet as Tootles

- Laurel Cronin as Liza, Granny Wendy's maid

- Phil Collins as Inspector Good

- Thomas Tulak as Too Small

- Alex Zuckerman as Latchboy

- Ahmad Stoner as No Nap

In addition, a number of celebrities and family members made brief credited and uncredited cameos in the film:[3] musicians David Crosby and Jimmy Buffett, Oscar-nominated actress Glenn Close, and former boxer Tony Burton appear as members of Hook's pirate crew; Star Wars director George Lucas and actress Carrie Fisher, play the kissing couple sprinkled with pixie dust; two of Hoffman's children, Jacob and Rebecca, both under 10-years-old during filming, briefly appeared in scenes in the "normal" world; and screenwriter Jim Hart's 11-year-old son Jake (who years earlier inspired his father with the question, "What if Peter Pan grew up?") plays one of Pan's Lost Boys.

Production

Inspiration

Spielberg found a close personal connection to Peter Pan's story from his own childhood. The troubled relationship between Peter and Jack in the film echoed Spielberg's relationship with his own father. Previous Spielberg films that explored a dysfunctional father-son relationship included E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. Peter's "quest for success" paralleled Spielberg starting out as a film director and transforming into a Hollywood business magnate.[4] "I think a lot of people today are losing their imagination because they are work-driven. They are so self-involved with work and success and arriving at the next plateau that children and family almost become incidental. I have even experienced it myself when I have been on a very tough shoot and I've not seen my kids except on weekends. They ask for my time and I can't give it to them because I'm working."[5] Like Peter at the beginning of the film, Spielberg has a fear of flying. He feels that Peter's "enduring quality" in the storyline is simply to fly. "Anytime anything flies, whether it's Superman, Batman, or E.T., it's got to be a tip of the hat to Peter Pan," Spielberg reflected in a 1992 interview. "Peter Pan was the first time I saw anybody fly. Before I saw Superman, before I saw Batman, and of course before I saw any superheroes, my first memory of anybody flying is in Peter Pan."[5]

Pre-production

The genesis of the film started when Spielberg's mother often read him Peter and Wendy as a bedtime story. He explained in 1985 "When I was 11 years old I actually directed the story during a school production. I have always felt like Peter Pan. I still feel like Peter Pan. It has been very hard for me to grow up, I'm a victim of the Peter Pan syndrome."[6]

In the early 1980s, Spielberg began to develop a film with Walt Disney Pictures that would have closely followed the storyline of the 1924 silent film and 1953 animated film.[5] He also considered directing it as a musical with Michael Jackson in the lead.[7] Jackson expressed interest in the part, but was not interested in Spielberg's vision of an adult Peter Pan who had forgotten about his past.[8] The project was taken to Paramount Pictures,[9] where James V. Hart wrote the first script with Dustin Hoffman already cast as Captain Hook.[7] It entered pre-production in 1985 for filming to begin at sound stages in England. Elliot Scott had been hired as production designer.[5] With the birth of his first son, Max, in 1985, Spielberg decided to drop out. "I decided not to make Peter Pan when I had my first child," Spielberg commented. "I didn't want to go to London and have seven kids on wires in front of blue screens. I wanted to be home as a dad."[7] Around this time, he considered directing Big, which carried similar motifs and themes with it.[7] In 1987, he "permanently abandoned" it, feeling he expressed his childhood and adult themes in Empire of the Sun.[10]

Meanwhile, Paramount and Hart moved forward on production with Nick Castle as director. Hart began to work on a new storyline when his son, Jake, showed his family a drawing. "We asked Jake what it was and he said it was a crocodile eating Captain Hook, but that the crocodile really didn't eat him, he got away," Hart reflected. "As it happens, I had been trying to crack Peter Pan for years, but I didn't just want to do a remake. So I went, 'Wow. Hook is not dead. The crocodile is. We've all been fooled'. In 1986 our family was having dinner and Jake said, 'Daddy, did Peter Pan ever grow up?' My immediate response was, 'No, of course not'. And Jake said, 'But what if he did?' I realized that Peter did grow up, just like all of us baby boomers who are now in our forties. I patterned him after several of my friends on Wall Street, where the pirates wear three-piece suits and ride in limos."[11]

Tom Hanks was Spielberg's original choice for the role of Peter Pan.[12]

Joseph Mazzello auditioned for the role of Jack Banning, he was turned down because he was deemed too young for the role. Mazzello was later cast as Tim Murphy in Jurassic Park.[13]

David Bowie, Christopher Lloyd, and Donald Sutherland were considered for Captain Hook.[14]

Filming

By 1989, Ian Rathbone changed the title to Hook, and took it from Paramount to TriStar Pictures, headed by Mike Medavoy, who was Spielberg's first talent agent. Robin Williams signed on, but he and Hoffman had creative differences with Castle. Medavoy saw the film as a vehicle for Spielberg and Castle was dismissed, but paid a $500,000 settlement.[11] Dodi Fayed, who owned certain rights to make a Peter Pan film, sold his interest to TriStar in exchange for an executive producer credit.[15] Spielberg briefly worked together with Hart to rewrite the script[5] before hiring Malia Scotch Marmo to rewrite Captain Hook's dialog and Carrie Fisher for Tinker Bell's.[16] The Writers Guild of America gave Hart and Marmo screenplay credit, while Hart and Castle were credited with the story. Fisher went uncredited. Filming began on February 19, 1991, occupying nine sound stages at Sony Pictures Studios in Culver City, California.[2] Stage 30 housed the Neverland Lost Boys playground, while Stage 10 supplied Captain Hook's ship cabin. Hidden hydraulics were installed to rock the set-piece to simulate a swaying ship, but the filmmakers found the movement distracted the dialogue, so the idea was dropped.[17]

Stage 27 housed the full-sized Jolly Roger and the surrounding Pirate Wharf.[17] Industrial Light & Magic provided the visual effects sequences. This marked the beginning of Tony Swatton's career, as he was asked to make weaponry for the film. It was financed by Amblin Entertainment and TriStar Pictures, with TriStar distributing it. Spielberg brought on John Napier as a "visual consultant", having been impressed with his work on Cats. The original production budget was set at $48 million, but ended up between $60–80 million.[18][19] The primary reason for the increased budget was the shooting schedule, which ran 40 days over its original 76-day schedule. Spielberg explained, "It was all my fault. I began to work at a slower pace than I usually do."[20]

Spielberg's on-set relationship with Julia Roberts was troubled, and he later admitted in an interview with 60 Minutes, "It was an unfortunate time for us to work together."[21] In a 1999 Vanity Fair interview, Roberts said that Spielberg's comments "really hurt my feelings." She "couldn't believe this person that I knew and trusted was actually hesitating to come to my defense...it was the first time that I felt I had a turncoat in my midst."[22]

Soundtrack

| Hook (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Film score by | ||||

| Released | November 26, 1991 (original) March 27, 2012 (reissue)[23] | |||

| Length | 75:18 (original) 140:34 (reissue) | |||

| Label | Epic Soundtrax (original) La-La Land Records (reissue) | |||

| John Williams chronology | ||||

| ||||

The film score was composed and conducted by John Williams. He was brought in at an early stage when Spielberg was considering making the film as a musical. Williams wrote around eight songs with lyricist Leslie Bricusse for the project at this stage.[24] Williams and Bricusse finalized it to five songs.[25] Several of these songs were recorded and some musical segments were even filmed. Julie Andrews recorded one song, "Childhood", at the Sony Pictures Studios so that Maggie Smith could lip-sync it on set; it was meant to be sung by Granny Wendy to her grandchildren in their bedroom.[25] Two additional songs, "Stick with Me" and "Low Below", performed by Dustin Hoffman and Bob Hoskins, respectively, were also rehearsed.[25] These three songs were ultimately cut from the film, and instead were incorporated into the instrumental score. Two remaining songs survive in the finished film: "We Don't Wanna Grow Up" and "When You're Alone", both with lyrics by Bricusse.[20] The track called "Prologue" as made appearances in trailers for Matilda, another film by TriStar.

The original 1991 issue was released by Epic Soundtrax.[26] In 2012, a limited edition of the soundtrack, called Hook: Expanded Original Motion Picture Soundtrack, was released by La-La Land Records and Sony Music.[23] It contains almost the complete score with alternates and unused material. It also contains liner notes that explain the film's production and score recording.

- Commercial songs from the film, but not on the soundtrack[24]

- "Pick'em Up" – Music by John Williams and lyrics by Leslie Bricusse

- "Take Me Out to the Ball Game" – Written by Jack Norworth and Albert Von Tilzer

Video games

A video game based on the film and bearing the same name was released for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System in 1991. The game was released for additional game consoles in 1992.[27] Another game was released for PC and Commodore Amiga, and is a Point and Click adventure game.

Reception

Box office

Spielberg, Williams, and Hoffman did not take salaries for the film. Their deal called for them to split 40% of TriStar Pictures' gross revenues. They were to receive $20 million from the first $50 million in gross theatrical film rentals, with TriStar keeping the next $70 million in rentals before the three resumed receiving their percentage.[2] The film was released in North America on December 11, 1991, earning $13.5 million in its opening weekend. It went on to gross $119.7 million in the United States and Canada and $181.2 million in foreign countries, accumulating a worldwide total of $300.9 million.[28] It is the sixth-highest-grossing "pirate-themed" film, behind all five films in the Pirates of the Caribbean film series.[29] In the United States and Canada, it was the sixth-highest-grossing film in 1991,[30] and fourth-highest-grossing worldwide.[31] It was the second highest-grossing film in Japan with theatrical rentals of $22.4 million.[32][33] It ended up making a profit of $50 million for the studio, yet it was still declared a financial disappointment,[34] having been overshadowed by the release of Disney's Beauty and the Beast and a decline in box-office receipts compared to the previous years.[35]

Critical response

Review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes reports that 29% of critics have given the film a positive review, based on 66 reviews, with an average rating of 4.70/10. The site's consensus states: "The look of Hook is lively indeed but Steven Spielberg directs on autopilot here, giving in too quickly to his sentimental, syrupy qualities."[36] On Metacritic, the film has a 52 out of 100 rating, based on reviews from 19 critics, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[37] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "A−" on an A+ to F scale.[38]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times wrote that:

The sad thing about the screenplay for Hook is that it's so correctly titled: This whole construction is really nothing more than a hook on which to hang a new version of the Peter Pan story. No effort is made to involve Peter's magic in the changed world he now inhabits, and little thought has been given to Captain Hook's extraordinary persistence in wanting to revisit the events of the past. The failure in Hook is its inability to re-imagine the material, to find something new, fresh or urgent to do with the Peter Pan myth. Lacking that, Spielberg should simply have remade the original story, straight, for this generation.[39]

Peter Travers of Rolling Stone magazine felt it would "only appeal to the baby boomer generation" and highly criticized the sword-fighting choreography.[40] Vincent Canby of The New York Times felt the story structure was not well balanced, feeling Spielberg depended too much on art direction.[41] Hal Hinson of The Washington Post was one of few who gave it a positive review. Hinson elaborated on crucial themes of children, adulthood, and loss of innocence. However, he said that Spielberg "was stuck too much in a theme park world".[42]

Accolades

The film was nominated for five categories at the 64th Academy Awards. This included Best Art Direction (Norman Garwood, Garrett Lewis) (lost to Bugsy), Best Costume Design (lost to Bugsy), Best Visual Effects (lost to Terminator 2: Judgment Day), Best Makeup (lost to Terminator 2: Judgment Day) and Best Original Song (for "When You're Alone"; lost to Beauty and the Beast).[43] It lost the Saturn Award for Best Fantasy Film to Aladdin, in which Williams co-starred,[44] while cinematographer Dean Cundey was nominated for his work by the American Society of Cinematographers.[45] Hoffman was nominated for the Golden Globe Award for Best Actor – Motion Picture Musical or Comedy (Hoffman actually lost to his co-star Robin Williams for his performance in The Fisher King).[46] John Williams was given a Grammy Award nomination for Best Score Soundtrack for Visual Media;[47] Julia Roberts received a Golden Raspberry Award nomination for Worst Supporting Actress (lost to Sean Young as the dead twin in A Kiss Before Dying).[48]

Legacy

In years since the release of the film, Steven Spielberg admitted in interviews that he was not proud of the film and disappointed with the final result. In 2011, he told Entertainment Weekly: "There are parts of Hook I love. I'm really proud of my work right up through Peter being hauled off in the parachute out the window, heading for Neverland. I'm a little less proud of the Neverland sequences because I'm uncomfortable with that highly stylized world that today, of course, I would probably have done with live-action character work inside a completely digital set. But we didn't have the technology to do it then, and my imagination only went as far as building physical sets and trying to paint trees blue and red."[49] Spielberg gave a more blunt assessment in a 2013 interview on Kermode & Mayo's Film Review Show: "I wanna see Hook again because I so don't like that movie, and I'm hoping someday I'll see it again and perhaps like some of it."[50]

In 2018, Spielberg told Empire, "I felt like a fish out of water making Hook... I didn't have confidence in the script. I had confidence in the first act and I had confidence in the epilogue. I didn't have confidence in the body of it." He added, "I didn't quite know what I was doing and I tried to paint over my insecurity with production value," admitting "the more insecure I felt about it, the bigger and more colorful the sets became."[51]

In a 2020 interview with Collider Games, actor Dante Basco revealed that he's working on an animated prequel series about his character Rufio.[52][53]

John Williams' musical score was particularly praised and is considered by many as one of his best.[54][55][56]

See also

- List of films featuring miniature people

References

- "Hook". British Board of Film Classification. January 17, 1992. Archived from the original on January 27, 2016. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- McBride 1997, p. 411.

- Doty, Meriah (December 11, 2016). "The Boy Who Inspired 'Hook' and 19 Other Little-Known Facts as Film Turns 25 (Photos)". TheWrap. Archived from the original on October 11, 2018. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- McBride 1997, p. 413.

- Steven Spielberg (March–April 1992). "Hook: Steven Spielberg". Cinema Papers (Interview). No. 87. Interviewed by Ana Maria Bahiana. pp. 12–16. Archived from the original on May 12, 2021. Retrieved December 21, 2019 – via issuu.

- McBride 1997, pp. 42–3.

- McBride 1997, p. 409.

- "Michael Jackson Was Steven Spielberg's First Choice To Play Peter Pan In 'Hook'". Starpulse.com. Archived from the original on February 8, 2012. Retrieved March 23, 2017.

- "Steven Spielberg's Hook: What Went Wrong?". Den of Geek. December 11, 2019. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Forsberg, Myra (January 10, 1988). "Spielberg at 40: The Man and the Child". The New York Times. New York, NY. Archived from the original on December 14, 2017. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- McBride 1997, p. 410.

- "The Lost Comedy Roles of Tom Hanks". Vulture. December 22, 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Spielberg's Protégé". NY Post. May 2, 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Hook (1991) - Trivia". IMDb.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Medavoy & Young 2002, p. 230.

- "Carrie Fisher Script Doctor: From Hook To Wedding Singer". /Film. December 29, 2016. Archived from the original on April 24, 2020. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- DVD production notes

- Park, Jeannie (December 23, 1991). "Ahoy! Neverland!". People. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - McBride 1997, pp. 410, 412.

- "13 Sharp Facts About Hook". Mental Floss. November 2, 2016. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Steven Spielberg on 60 Minutes". YouTube. CBS.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) (Timestamp 8:08). Retrieved December 21, 2021. - Desta, Yohana (August 19, 2016). "15 On-Set Beefs That Will Go Down in Hollywood History". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on April 29, 2018. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- "HOOK 2CD Set Includes 'Over 65 minutes of Music Previously Unreleased'". JOHN WILLIAMS Fan Network. May 20, 2012. Archived from the original on April 28, 2012. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- "HOOK (1991) – Complete Score Analysis (2000)". JOHN WILLIAMS Fan Network. February 13, 2000. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

- Grieving, Tim (December 8, 2021). "Steven Spielberg's Eternal Quest for Song and Dance". theringer.com. Retrieved August 13, 2022.

- "Hook - John Williams". AllMusic. Archived from the original on August 28, 2012. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- Marriott, Scott Alan. "Hook – Overview (SNES)". AllGame. Archived from the original on November 15, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- "Hook (1991)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on December 19, 2008. Retrieved September 19, 2008.

- "Pirate Movies at the Box Office". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Retrieved June 3, 2011.

- "1991 Yearly Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on December 16, 2008. Retrieved September 19, 2008.

- "1991 Yearly Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on December 18, 2008. Retrieved September 19, 2008.

- "Top 10 grossers in Japan: 1992". Variety. September 27, 1993. p. 57.

- "Kako haikyū shūnyū jōi sakuhin 1992-nen" (in Japanese). Motion Picture Producers Association of Japan. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- Dretzka, Gary (December 8, 1996). "Medavoy's Method". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on October 11, 2018. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- Medavoy & Young 2002, pp. 234–235.

- "Hook (1991)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Archived from the original on January 8, 2019. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- "Hook Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on October 31, 2015. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- "Cinemascore :: Movie Title Search". December 20, 2018. Archived from the original on December 20, 2018. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- Ebert, Roger (December 11, 1991). "Hook Movie Review & Film Summary (1991)". Chicago Sun Times. Archived from the original on January 11, 2015. Retrieved September 19, 2008.

- Travers, Peter (December 11, 1992). "Hook". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on June 16, 2008. Retrieved September 19, 2008.

- Canby, Vincent (December 11, 1991). "Review/Film; Peter as a Middle-Aged Master of the Universe". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 11, 2018. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- Hinson, Hal (December 11, 1991). "Hook". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 29, 2017. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- "1992 | Oscars.org". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Past Saturn Awards". Saturn Awards.com. Archived from the original on February 10, 2005. Retrieved September 20, 2008.

- "7th Annual Awards". American Society of Cinematographers. Archived from the original on November 9, 2006. Retrieved September 20, 2008.

- "49th Golden Globe Awards". Internet Movie Database. Archived from the original on December 24, 2008. Retrieved September 20, 2008.

- "Grammy Awards of 1991". Internet Movie Database. Archived from the original on February 12, 2006. Retrieved September 20, 2008.

- "Twelfth Annual RAZZIE Awards". Golden Raspberry Award. Archived from the original on December 23, 2007. Retrieved October 15, 2008.

- Breznican, Anthony (December 2, 2011). "Steven Spielberg: The EW interview". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on October 11, 2018. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- Kermode, Mark; Mayo, Simon (January 25, 2013). "Steven Spielberg interviewed by Kermode & Mayo". Kermode and Mayo's Film Review. Archived from the original on April 17, 2016. Retrieved February 18, 2016 – via YouTube.

- Brew, Simon (February 22, 2018). "Why Steven Spielberg Was Unhappy With Hook". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on March 27, 2018. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- "Dante Basco Talks Artificial Season 3, Rufio's Legacy and Being Part of the Last Airbender Family". Revog. YouTube. July 7, 2020. Archived from the original on July 13, 2020. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- "@dantebasco revealed he's working on an animated prequel series about his iconic character #Rufio!". Revog Games. July 7, 2020. Archived from the original on July 7, 2020. Retrieved July 7, 2020 – via Twitter.

- Hicks, Chris (January 11, 1992). "'HOOK' COMPOSER SCORES BIG WITH COLLECTION OF MOVIE THEMES". Deseret News. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "The Top 10 John Williams Scores of All Time". Collider. December 18, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "15 Legendary John Williams Film Scores". Musicnotes.com. October 17, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)

Bibliography

- Brooks, Terry (1991). Hook (Hardcover). novelization of the film. Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-449-90707-4.

- Charles L.P. Silet (2002). The Films of Steven Spielberg. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-4182-7.

- McBride, Joseph (1997). Steven Spielberg: A Biography. New York City: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-19177-0.

- Medavoy, Mike; Young, Josh (2002). You're Only as Good as Your Next One: 100 Great Films, 100 Good Films, and 100 for Which I Should Be Shot. New York City: Atria Books. ISBN 978-0743400558.

External links

- Hook at IMDb

- Hook at the TCM Movie Database

- Hook at Box Office Mojo

- Hook at Rotten Tomatoes

- Hook at Metacritic

- Sony Imagesoft's Hook at MobyGames

- Ocean's Hook at MobyGames