Hummingbird

Hummingbirds are birds native to the Americas and comprise the biological family Trochilidae. With about 361 species and 113 genera,[1] they occur from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego, but the vast majority of the species are found in the tropics around the equator. They are small birds, with most species measuring 7.5–13 cm (3–5 in) in length. The smallest extant hummingbird species is the 5 cm (2.0 in) bee hummingbird, which weighs less than 2.0 g (0.07 oz). The largest hummingbird species is the 23 cm (9.1 in) giant hummingbird, weighing 18–24 grams (0.63–0.85 oz). They are specialized for feeding on flower nectar, but all species also consume flying insects or spiders.

| Hummingbird Temporal range: Rupelian | |

|---|---|

| |

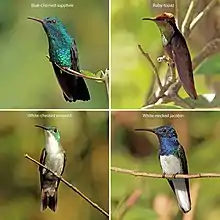

| Four hummingbirds from Trinidad and Tobago | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Apodiformes |

| Family: | Trochilidae Vigors, 1825 |

| Subfamilies | |

|

†Eurotrochilus | |

Hummingbirds split from their sister group, the swifts and treeswifts, around 42 million years ago. The common ancestor of extant hummingbirds is estimated to have lived 22 million years ago in South America. They are known as hummingbirds because of the humming sound created by their beating wings, which flap at high frequencies audible to humans. They hover in mid-air at rapid wing-flapping rates, which vary from around 12 beats per second in the largest species to around 80 per second in small hummingbirds. Of those species that have been measured during flying in wind tunnels, their top speeds exceed 15 m/s (54 km/h; 34 mph). During courtship, some male species dive from 30 metres (100 ft) of height above a female at speeds around 23 m/s (83 km/h; 51 mph).[2][3]

Hummingbirds have the highest mass-specific metabolic rate of any homeothermic animal.[4] To conserve energy when food is scarce and at night when not foraging, they can enter torpor, a state similar to hibernation, and slow their metabolic rate to 1/15 of its normal rate.[5]

Taxonomy and systematics

The family Trochilidae was introduced in 1825 by Irish zoologist Nicholas Aylward Vigors with Trochilus as the type genus.[6][7] Molecular phylogenetic studies of the hummingbirds have shown that the family is composed of nine major clades.[8][9] When Edward Dickinson and James Van Remsen Jr. updated the Howard and Moore Complete Checklist of the Birds of the World for the 4th edition in 2013, they divided the hummingbirds into six subfamilies.[10]

Molecular phylogenetic studies determined the relationships between the major groups of hummingbirds.[9][11] In the cladogram below, the English names are those introduced in 1997.[12] The Latin names are those introduced in 2013.[13]

| Trochilidae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In traditional taxonomy, hummingbirds are placed in the order Apodiformes, which also contains the swifts, but some taxonomists have separated them into their own order, the Trochiliformes. Hummingbirds' wing bones are hollow and fragile, making fossilization difficult and leaving their evolutionary history poorly documented. Though scientists theorize that hummingbirds originated in South America, where species diversity is greatest, possible ancestors of extant hummingbirds may have lived in parts of Europe and what is southern Russia today.[14]

Around 360 hummingbirds have been described. They have been traditionally divided into two subfamilies: the hermits (subfamily Phaethornithinae) and the typical hummingbirds (subfamily Trochilinae, all the others). Molecular phylogenetic studies have shown, though, that the hermits are sister to the topazes, making the former definition of the Trochilinae not monophyletic. The hummingbirds form nine major clades: the topazes and jacobins, the hermits, the mangoes, the coquettes, the brilliants, the giant hummingbird (Patagona gigas), the mountaingems, the bees, and the emeralds.[9] The topazes and jacobins combined have the oldest split with the rest of the hummingbirds. The hummingbird family has the third-greatest number of species of any bird family (after the tyrant flycatchers and the tanagers).[9][15]

Fossil hummingbirds are known from the Pleistocene of Brazil and the Bahamas, but neither has yet been scientifically described, and fossils and subfossils of a few extant species are known. Until recently, older fossils had not been securely identifiable as those of hummingbirds.

In 2004, Gerald Mayr identified two 30-million-year-old hummingbird fossils. The fossils of this primitive hummingbird species, named Eurotrochilus inexpectatus ("unexpected European hummingbird"), had been sitting in a museum drawer in Stuttgart; they had been unearthed in a clay pit at Wiesloch–Frauenweiler, south of Heidelberg, Germany, and, because hummingbirds were assumed to have never occurred outside the Americas, were not recognized to be hummingbirds until Mayr took a closer look at them.[14][16]

Fossils of birds not clearly assignable to either hummingbirds or a related extinct family, the Jungornithidae, have been found at the Messel pit and in the Caucasus, dating from 35 to 40 million years ago; this indicates that the split between these two lineages indeed occurred around that time. The areas where these early fossils have been found had a climate quite similar to that of the northern Caribbean or southernmost China during that time. The biggest remaining mystery at present is what happened to hummingbirds in the roughly 25 million years between the primitive Eurotrochilus and the modern fossils. The astounding morphological adaptations, the decrease in size, and the dispersal to the Americas and extinction in Eurasia all occurred during this timespan. DNA–DNA hybridization results suggest that the main radiation of South American hummingbirds took place at least partly in the Miocene, some 12 to 13 million years ago, during the uplifting of the northern Andes.[17]

In 2013, a 50-million-year-old bird fossil unearthed in Wyoming was found to be a predecessor to both hummingbirds and swifts before the groups diverged.[18]

Evolution

Hummingbirds are thought to have split from other members of Apodiformes, the insectivorous swifts (family Apodidae) and treeswifts (family Hemiprocnidae), about 42 million years ago, probably in Eurasia.[9] Despite their current New World distribution, the earliest known species of hummingbird are known from the early Oligocene (Rupelian ~34–28 million years ago) of Europe, belonging to the genus Eurotrochilus, which is very similar in its morphology to modern hummingbirds.[16][19][20] A phylogenetic tree unequivocally indicates that modern hummingbirds originated in South America, with the last common ancestor of all living hummingbirds living around 22 million years ago.[9]

A map of the hummingbird family tree – reconstructed from analysis of 284 of the world's 338 known species – shows rapid diversification from 22 million years ago.[21] Hummingbirds fall into nine main clades – the topazes, hermits, mangoes, brilliants, coquettes, the giant hummingbird, mountaingems, bees, and emeralds – defining their relationship to nectar-bearing flowering plants and the birds' continued spread into new geographic areas.[21][8][9][22]

While all hummingbirds depend on flower nectar to fuel their high metabolisms and hovering flight, coordinated changes in flower and bill shape stimulated the formation of new species of hummingbirds and plants. Due to this exceptional evolutionary pattern, as many as 140 hummingbird species can coexist in a specific region, such as the Andes range.[21]

The hummingbird evolutionary tree shows one key evolutionary factor appears to have been an altered taste receptor that enabled hummingbirds to seek nectar.[23]

The Andes Mountains appear to be a particularly rich environment for hummingbird evolution because diversification occurred simultaneously with mountain uplift over the past 10 million years.[21] Hummingbirds remain in dynamic diversification inhabiting ecological regions across South America, North America, and the Caribbean, indicating an enlarging evolutionary radiation.[21]

Within the same geographic region, hummingbird clades co-evolved with nectar-bearing plant clades, affecting mechanisms of pollination.[24][25] The same is true for the sword-billed hummingbird (Ensifera ensifera), one of the morphologically most extreme species, and one of its main food plant clades (Passiflora section Tacsonia).[26]

_JCB.jpg.webp)

Sexual dimorphisms

Hummingbirds exhibit sexual size dimorphism according to Rensch's rule,[27] in which males are smaller than females in small-bodied species, and males are larger than females in large-bodied species.[28] The extent of this sexual size difference varies among clades of hummingbirds.[28][29] For example, the Mellisugini clade (bees) exhibits a large size dimorphism, with females being larger than males.[29] Conversely, the Lesbiini clade (coquettes) displays very little size dimorphism; males and females are similar in size.[29] Sexual dimorphisms in bill size and shape are also present between male and female hummingbirds,[29] where in many clades, females have longer, more curved bills favored for accessing nectar from tall flowers.[30] For males and females of the same size, females tend to have larger bills.[29]

Sexual size and bill differences likely evolved due to constraints imposed by courtship, because mating displays of male hummingbirds require complex aerial maneuvers.[27] Males tend to be smaller than females, allowing conservation of energy to forage competitively and participate more frequently in courtship.[27] Thus, sexual selection favors smaller male hummingbirds.[27]

Female hummingbirds tend to be larger, requiring more energy, with longer beaks that allow for more effective reach into crevices of tall flowers for nectar.[30] Thus, females are better at foraging, acquiring flower nectar, and supporting the energy demands of their larger body size.[30] Directional selection thus favors the larger hummingbirds in terms of acquiring food.[28]

Another evolutionary cause of this sexual bill dimorphism is that the selective forces from competition for nectar between the sexes of each species drives sexual dimorphism.[29] Depending on which sex holds territory in the species, the other sex having a longer bill and being able to feed on a wide variety of flowers is advantageous, decreasing intraspecific competition.[30] For example, in species of hummingbirds where males have longer bills, males do not hold a specific territory and have a lek mating system.[30] In species where males have shorter bills than females, males defend their resources, so females benefit from a longer bill to feed from a broader range of flowers.[30]

Co-evolution with ornithophilous flowers

Hummingbirds are specialized nectarivores[31] and are tied to the ornithophilous flowers upon which they feed. This coevolution implies that morphological traits of hummingbirds, such as bill length, bill curvature, and body mass are correlated with morphological traits of plants, for example corolla length, curvature, and volume.[32] Some species, especially those with unusual bill shapes, such as the sword-billed hummingbird and the sicklebills, are co-evolved with a small number of flower species. Even in the most specialized hummingbird–plant mutualisms, though, the number of food plant lineages of the individual hummingbird species increases with time.[33] The bee hummingbird (Mellisuga helenae) – the world's smallest bird – evolved to dwarfism likely because it had to compete with long-billed hummingbirds having an advantage for nectar foraging from specialized flowers, consequently leading the bee hummingbird to more successfully compete for flower foraging against insects.[34][35]

Many plants pollinated by hummingbirds produce flowers in shades of red, orange, and bright pink, though the birds take nectar from flowers of other colors as well. Hummingbirds can see wavelengths into the near-ultraviolet, but hummingbird-pollinated flowers do not reflect these wavelengths as many insect-pollinated flowers do. This narrow color spectrum may render hummingbird-pollinated flowers relatively inconspicuous to most insects, thereby reducing nectar robbing.[36][37] Hummingbird-pollinated flowers also produce relatively weak nectar (averaging 25% sugars w/w) containing a high proportion of sucrose, whereas insect-pollinated flowers typically produce more concentrated nectars dominated by fructose and glucose.[38]

Hummingbirds and the plants they visit for nectar have a tight co-evolutionary association, generally called a plant–bird mutualistic network.[39] These birds show high specialization and modularity, especially in communities with high species richness. These associations are also observed when closely related hummingbirds, for example two species of the same genus, visit distinct sets of flowering species.[39][40]

Bill evolution

Upon maturity, males of a particular species, Phaethornis longirostris, the long-billed hermit, appear to be evolving a dagger-like weapon on the beak tip as a secondary sexual trait to defend mating areas.[41]

Specialized characteristics and metabolism

Humming

Hummingbirds are named for the prominent humming sound their wingbeats make while flying and hovering to feed or interact with other hummingbirds.[42] Humming serves communication purposes by alerting other birds of the arrival of a fellow forager or potential mate.[42] The humming sound derives from aerodynamic forces generated by both the downstrokes and upstrokes of the rapid wingbeats, causing oscillations and harmonics that evoke an acoustic quality likened to that of a musical instrument.[42][43] The humming sound of hummingbirds is unique among flying animals, compared to the whine of mosquitoes, buzz of bees, and "whoosh" of larger birds.[42][43]

The wingbeats causing the hum of hummingbirds during hovering are achieved by elastic recoil of wing strokes produced by the main flight muscles: the pectoralis major (the main downstroke muscle) and supracoracoideus (the main upstroke muscle).[44]

Wingbeats and flight stability

_RWD4.jpg.webp)

The highest recorded wingbeats for wild hummingbirds during hovering is 88 per second, as measured for the purple-throated woodstar (Calliphlox mitchellii) weighing 3.2 g.[45] The number of beats per second increases above "normal" while hovering during courtship displays (up to 90 per second for the calliope hummingbird, Stellula calliope), a wingbeat rate 40% higher than its typical hovering rate.[46]

During turbulent airflow conditions created experimentally in a wind tunnel, hummingbirds exhibit stable head positions and orientation when they hover at a feeder.[47] When wind gusts from the side, hummingbirds compensate by increasing wing-stroke amplitude and stroke plane angle and by varying these parameters asymmetrically between the wings and from one stroke to the next.[47] They also vary the orientation and enlarge the collective surface area of their tail feathers into the shape of a fan.[47] While hovering, the visual system of a hummingbird is able to separate apparent motion caused by the movement of the hummingbird itself from motions caused by external sources, such as an approaching predator.[48] In natural settings full of highly complex background motion, hummingbirds are able to precisely hover in place by rapid coordination of vision with body position.[48]

Vision

Although hummingbird eyes are small in diameter (5–6 mm), they are accommodated in the skull by reduced skull ossification, and occupy a relatively larger proportion of the skull compared to other birds and animals.[49] Further, hummingbird eyes have relatively large corneas, which comprise about 50% of the total transverse eye diameter, combined with an extraordinary density of retinal ganglion cells responsible for visual processing, containing some 45,000 neurons per mm2.[50] The enlarged cornea relative to total eye diameter serves to increase the amount of light perception by the eye when the pupil is dilated maximally, enabling nocturnal flight.[50]

During evolution, hummingbirds adapted to the navigational needs of visual processing while in rapid flight or hovering by development of the exceptionally dense array of retinal neurons, allowing for increased spatial resolution in the lateral and frontal visual fields.[50] Morphological studies of the hummingbird brain showed that neuronal hypertrophy – relatively the largest in any bird – exists in a region called the pretectal nucleus lentiformis mesencephali (called the nucleus of the optic tract in mammals) responsible for refining dynamic visual processing while hovering and during rapid flight.[51][52]

The enlargement of the brain region responsible for visual processing indicates an enhanced ability for perception and processing of fast-moving visual stimuli which hummingbirds encounter during rapid forward flight, insect foraging, competitive interactions, and high-speed courtship.[52][53] A study of broad-tailed hummingbirds indicated that hummingbirds have a fourth color-sensitive visual cone (humans have three) that detects ultraviolet light and enables discrimination of non-spectral colors, possibly having a role in courtship displays, territorial defense, and predator evasion.[54] The fourth color cone would extend the range of visible colors for hummingbirds to perceive ultraviolet light and color combinations of feathers and gorgets, colorful plants, and other objects in their environment, enabling detection of as many as five non-spectral colors, including purple, ultraviolet-red, ultraviolet-green, ultraviolet-yellow, and ultraviolet-purple.[54]

Hummingbirds are highly sensitive to stimuli in their visual fields, responding to even minimal motion in any direction by reorienting themselves in midflight.[48][52][53] Their visual sensitivity allows them to precisely hover in place while in complex and dynamic natural environments,[48] functions enabled by the lentiform nucleus which is tuned to fast-pattern velocities, enabling highly tuned control and collision avoidance during forward flight.[52]

Metabolism

With the exception of insects, hummingbirds while in flight have the highest metabolism of all animals – a necessity to support the rapid beating of their wings during hovering and fast forward flight.[4][55] Their heart rate can reach as high as 1,260 beats per minute (bpm), a rate once measured in a blue-throated hummingbird, with a breathing rate of 250 bpm, even at rest.[56][57] During flight, oxygen consumption per gram of muscle tissue in a hummingbird is about 10 times higher than that measured in elite human athletes.[4]

Hummingbirds are rare among vertebrates in their ability to rapidly make use of ingested sugars to fuel energetically expensive hovering flight,[58] powering up to 100% of their metabolic needs with the sugars they drink (in comparison, human athletes maximize around 30%). Hummingbirds can use newly ingested sugars to fuel hovering flight within 30–45 minutes of consumption.[59][60] These data suggest that hummingbirds are able to oxidize sugar in flight muscles at rates high enough to satisfy their extreme metabolic demands. A 2017 review indicated that hummingbirds have in their flight muscles a mechanism for "direct oxidation" of sugars into maximal ATP yield to support their high metabolic rate for hovering, foraging at altitude, and migrating.[61]

By relying on newly ingested sugars to fuel flight, hummingbirds can reserve their limited fat stores to sustain their overnight fasting or to power migratory flights.[59] Studies of hummingbird metabolism address how a migrating ruby-throated hummingbird can cross 800 km (500 mi) of the Gulf of Mexico on a nonstop flight.[57] This hummingbird, like other long-distance migrating birds, stores fat as a fuel reserve augmenting its weight by as much as 100%, then enabling metabolic fuel for flying over open water.[57][62]

Hemoglobin adaptation to altitude

Dozens of hummingbird species live year-round in tropical mountain habitats at high altitudes, such as in the Andes over ranges of 1,500 metres (4,900 ft) to 5,200 metres (17,100 ft) where the oxygen content of air is reduced, a condition of hypoxic challenge for the high metabolic demands of hummingbirds.[63][64][65] In Andean hummingbirds living at high elevations, researchers found that the oxygen-carrying protein in blood – hemoglobin – had increased oxygen-binding affinity, and that this adaptive effect likely resulted from evolutionary mutations within the hemoglobin molecule via specific amino acid changes due to natural selection.[63][64][66]

Heat dissipation

The high metabolic rate of hummingbirds – especially during rapid forward flight and hovering – produces increased body heat that requires specialized mechanisms of thermoregulation for heat dissipation, which becomes an even greater challenge in hot, humid climates.[67] Hummingbirds dissipate heat partially by evaporation through exhaled air, and from body structures with thin or no feather covering, such as around the eyes, shoulders, under the wings (patagia), and feet.[68][69]

While hovering, hummingbirds do not benefit from the heat loss by air convection during forward flight, except for air movement generated by their rapid wing-beat, possibly aiding convective heat loss from the extended feet.[67][70] Smaller hummingbird species, such as the calliope, appear to adapt their relatively higher surface-to-volume ratio to improve convective cooling from air movement by the wings.[67] When air temperatures rise above 36 °C (97 °F), thermal gradients driving heat passively by convective dissipation from around the eyes, shoulders, and feet are reduced or eliminated, requiring heat dissipation mainly by evaporation and exhalation.[67] In cold climates, hummingbirds retract their feet into breast feathers to eliminate skin exposure and minimize heat dissipation.[70]

Kidney function

The dynamic range of metabolic rates in hummingbirds[71] requires a parallel dynamic range in kidney function.[72] During a day of nectar consumption with a corresponding high water intake that may total five times the body weight per day, hummingbird kidneys process water via glomerular filtration rates (GFR) in amounts proportional to water consumption, thereby avoiding overhydration.[72][73] During brief periods of water deprivation, however, such as in nighttime torpor, GFR drops to zero, preserving body water.[72][73]

Hummingbird kidneys also have a unique ability to control the levels of electrolytes after consuming nectars with high amounts of sodium and chloride or none, indicating that kidney and glomerular structures must be highly specialized for variations in nectar mineral quality.[74] Morphological studies on Anna's hummingbird kidneys showed adaptations of high capillary density in close proximity to nephrons, allowing for precise regulation of water and electrolytes.[73][75]

Song and vocal learning

Consisting of chirps, squeaks, whistles and buzzes,[76] hummingbird songs originate from at least seven specialized nuclei in the forebrain.[77][78] A genetic expression study showed that these nuclei enable vocal learning (ability to acquire vocalizations through imitation), a rare trait known to occur in only two other groups of birds (parrots and songbirds) and a few groups of mammals (including humans, whales and dolphins, and bats).[77] Within the past 66 million years, only hummingbirds, parrots, and songbirds out of 23 bird orders may have independently evolved seven similar forebrain structures for singing and vocal learning, indicating that evolution of these structures is under strong epigenetic constraints possibly derived from a common ancestor.[77][79]

The blue-throated hummingbird's song differs from typical oscine songs in its wide frequency range, extending from 1.8 kHz to about 30 kHz.[80] It also produces ultrasonic vocalizations which do not function in communication.[80] As blue-throated hummingbirds often alternate singing with catching small flying insects, it is possible the ultrasonic clicks produced during singing disrupt insect flight patterns, making insects more vulnerable to predation.[80]

The avian vocal organ, the syrinx, plays an important role in understanding hummingbird song production.[81] What makes the hummingbird's syrinx different from that of other birds in the Apodiformes order is the presence of internal muscle structure, accessory cartilages, and a large tympanum that serves as an attachment point for external muscles, all of which are adaptations thought to be responsible for the hummingbird's increased ability in pitch control and large frequency range.[81][82]

Torpor

The metabolism of hummingbirds can slow at night or at any time when food is not readily available; the birds enter a hibernatory, deep-sleep state (known as torpor) to prevent energy reserves from falling to a critical level. One study of broad-tailed hummingbirds found that body weight decreased linearly throughout torpor at a rate of 0.04 g per hour.[72]

During nighttime torpor, body temperature in a Caribbean hummingbird was shown to fall from 40 to 18 °C,[83] with heart and breathing rates both slowed dramatically (heart rate of roughly 50 to 180 bpm from its daytime rate of higher than 1000 bpm).[84] Recordings from a Metallura phoebe hummingbird in noctural torpor at around 3,800 metres (12,500 ft) in the Andes mountains showed that body temperature fell to 3.3 °C (38 °F), the lowest known level for a bird or non-hibernating mammal.[85][86] During cold nights at altitude, hummingbirds were in torpor for 2-13 hours depending on species, with cooling occurring at the rate of 0.6 °C per minute and rewarming at 1-1.5 °C per minute.[85] High-altitude Andean hummingbirds also lost body weight in negative proportion to how long the birds were in torpor, losing about 6% of weight each night.[85]

During torpor, to prevent dehydration, the kidney function declines, preserving needed compounds, such as glucose, water, and nutrients.[72] The circulating hormone, corticosterone, is one signal that arouses a hummingbird from torpor.[87]

Use and duration of torpor vary among hummingbird species and are affected by whether a dominant bird defends territory, with nonterritorial subordinate birds having longer periods of torpor.[88] A hummingbird with a higher fat percentage will be less likely to enter a state of torpor compared to one with less fat, as a bird can use the energy from its fat stores.[89] Torpor in hummingbirds appears to be unrelated to nighttime temperature, as it occurs across a wide temperature range, with energy savings of such deep sleep being more related to the photoperiod and duration of torpor.[89]

Lifespan

Hummingbirds have unusually long lifespans for organisms with such rapid metabolisms. Though many die during their first year of life, especially in the vulnerable period between hatching and fledging, those that survive may occasionally live a decade or more.[90] Among the better-known North American species, the typical lifespan is probably 3 to 5 years.[90] For comparison, the smaller shrews, among the smallest of all mammals, seldom live longer than 2 years.[91] The longest recorded lifespan in the wild relates to a female broad-tailed hummingbird that was banded (ringed) as an adult at least one year old, then recaptured 11 years later, making her at least 12 years old.[92] Other longevity records for banded hummingbirds include an estimated minimum age of 10 years 1 month for a female black-chinned hummingbird similar in size to the broad-tailed hummingbird, and at least 11 years 2 months for a much larger buff-bellied hummingbird.[93]

Predators

Praying mantises have been observed as predators of hummingbirds.[94][95][96] Other predators include dragonflies, frogs, orb-weaver spiders, and other birds, such as the roadrunner.[97]

Reproduction

Male hummingbirds do not take part in nesting.[98] Most species build a cup-shaped nest on the branch of a tree or shrub.[99] The nest varies in size relative to the particular species – from smaller than half a walnut shell to several centimeters in diameter.[98][100]

Many hummingbird species use spider silk and lichen to bind the nest material together and secure the structure.[99][101] The unique properties of the silk allow the nest to expand as the young hummingbirds grow.[99][100] Two white eggs are laid,[99][101] which despite being the smallest of all bird eggs are large relative to the adult hummingbird's size.[100] Incubation lasts 14 to 23 days,[101] depending on the species, ambient temperature, and female attentiveness to the nest.[98] The mother feeds her nestlings on small arthropods and nectar by inserting her bill into the open mouth of a nestling, and then regurgitating the food into its crop.[98][100] Hummingbirds stay in the nest for 18–22 days, after which they leave the nest to forage on their own, although the mother bird may continue feeding them for another 25 days.[102]

Feather colors

To serve courtship and territorial competition, many male hummingbirds have plumage with bright, varied coloration[103] resulting both from pigmentation in the feathers and from prismal cells within the top layers of feathers of the head, gorget, breast, back and wings.[104] When sunlight hits these cells, it is split into wavelengths that reflect to the observer in varying degrees of intensity,[104] with the feather structure acting as a diffraction grating.[104] Iridescent hummingbird colors result from a combination of refraction and pigmentation, since the diffraction structures themselves are made of melanin, a pigment,[103] and may also be colored by carotenoid pigmentation and more subdued black, brown or gray colors dependent on melanin.[104]

By merely shifting position, feather regions of a muted-looking bird can instantly become fiery red or vivid green.[104] In courtship displays for one example, males of the colorful Anna's hummingbird orient their bodies and feathers toward the sun to enhance the display value of iridescent plumage toward a female of interest.[105]

One study of Anna's hummingbirds found that dietary protein was an influential factor in feather color, as birds receiving more protein grew significantly more colorful crown feathers than those fed a low-protein diet.[106] Additionally, birds on a high-protein diet grew yellower (higher hue) green tail feathers than birds on a low-protein diet.[106]

Aerodynamics of flight

Hummingbird flight has been studied intensively from an aerodynamic perspective using wind tunnels and high-speed video cameras.

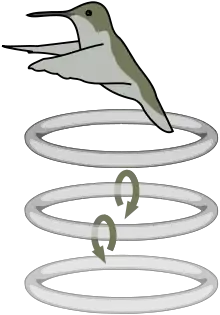

Two studies of rufous or Anna's hummingbirds in a wind tunnel used particle image velocimetry techniques to investigate the lift generated on the bird's upstroke and downstroke.[108][109] The birds produced 75% of their weight support during the downstroke and 25% during the upstroke, with the wings making a "figure 8" motion.[110]

Many earlier studies had assumed that lift was generated equally during the two phases of the wingbeat cycle, as is the case of insects of a similar size.[108] This finding shows that hummingbird hovering is similar to, but distinct from, that of hovering insects such as the hawk moth.[108] Further studies using electromyography in hovering rufous hummingbirds showed that muscle strain in the pectoralis major (principal downstroke muscle) was the lowest yet recorded in a flying bird, and the primary upstroke muscle (supracoracoideus) is proportionately larger than in other bird species.[111] Presumably due to rapid wingbeats for flight and hovering, hummingbird wings have adapted to perform without an alula.[112]

The giant hummingbird's wings beat as few as 12 per second,[113] and the wings of typical hummingbirds beat up to 80 times per second.[114] As air density decreases, for example, at higher altitudes, the amount of power a hummingbird must use to hover increases. Hummingbird species adapted for life at higher altitudes, therefore, have larger wings to help offset these negative effects of low air density on lift generation.[115]

A slow-motion video has shown how the hummingbirds deal with rain when they are flying. To remove the water from their heads, they shake their heads and bodies, similar to a dog shaking, to shed water.[116] Further, when raindrops collectively may weigh as much as 38% of the bird's body weight, hummingbirds shift their bodies and tails horizontally, beat their wings faster, and reduce their wings' angle of motion when flying in heavy rain.[117]

Feather sonation

Courtship dives

When courting, the male Anna's hummingbird ascends some 35 m (115 ft) above a female, before diving at a speed of 27 m/s (89 ft/s), equal to 385 body lengths/sec – producing a high-pitched sound near the female at the nadir of the dive.[118] This downward acceleration during a dive is the highest reported for any vertebrate undergoing a voluntary aerial maneuver; in addition to acceleration, the speed, relative to body length, is the highest known for any vertebrate. For instance, it is about twice the diving speed of peregrine falcons in pursuit of prey.[118] At maximum descent speed, about 10 g of gravitational force occur in the courting hummingbird during a dive (Note: G-force is generated as the bird pulls out of the dive).[118] By comparison to humans, this is a G-force acceleration well beyond the threshold of causing near loss of consciousness in fighter pilots (occurring at about +5 Gz) during flight of fixed-wing aircraft in a high-speed banked turn.[118][119]

The outer tail feathers of male Anna's (Calypte anna) and Selasphorus hummingbirds (e.g., Allen's, calliope) vibrate during courtship display dives and produce an audible chirp caused by aeroelastic flutter.[120][121] Hummingbirds cannot make the courtship dive sound when missing their outer tail feathers, and those same feathers could produce the dive sound in a wind tunnel.[120] The bird can sing at the same frequency as the tail-feather chirp, but its small syrinx is not capable of the same volume.[122] The sound is caused by the aerodynamics of rapid air flow past tail feathers, causing them to flutter in a vibration, which produces the high-pitched sound of a courtship dive.[120][123]

Many other species of hummingbirds also produce sounds with their wings or tails while flying, hovering, or diving, including the wings of the calliope hummingbird,[124] broad-tailed hummingbird, rufous hummingbird, Allen's hummingbird, and the streamertail species, as well as the tail of the Costa's hummingbird and the black-chinned hummingbird, and a number of related species.[125] The harmonics of sounds during courtship dives vary across species of hummingbirds.[121]

Wing feather trill

Male rufous and broad-tailed hummingbirds (genus Selasphorus) have a distinctive wing feature during normal flight that sounds like jingling or a buzzing shrill whistle.[126] The trill arises from air rushing through slots created by the tapered tips of the ninth and tenth primary wing feathers, creating a sound loud enough to be detected by female or competitive male hummingbirds and researchers up to 100 m away.[126]

Behaviorally, the trill serves several purposes:[126]

- Announces the sex and presence of a male bird

- Provides audible aggressive defense of a feeding territory and an intrusion tactic

- Enhances communication of a threat

- Favors mate attraction and courtship

Range

Hummingbirds are restricted to the Americas from south central Alaska to Tierra del Fuego, including the Caribbean. The majority of species occur in tropical and subtropical Central and South America, but several species also breed in temperate climates and some hillstars occur even in alpine Andean highlands at altitudes up to 5,200 m (17,100 ft).[127]

The greatest species richness is in humid tropical and subtropical forests of the northern Andes and adjacent foothills, but the number of species found in the Atlantic Forest, Central America or southern Mexico also far exceeds the number found in southern South America, the Caribbean islands, the United States, and Canada. While fewer than 25 different species of hummingbirds have been recorded from the United States and fewer than 10 from Canada and Chile each,[128] Colombia alone has more than 160[129] and the comparably small Ecuador has about 130 species.[130]

The migratory ruby-throated hummingbird breeds in a range from the Southeastern United States to Ontario,[131] while the black-chinned hummingbird, its close relative and another migrant, is the most widespread and common species in the southwestern United States. The rufous hummingbird is the most widespread species in western North America,[132] and the only hummingbird to be recorded outside of the Americas, having occurred in the Chukchi Peninsula of Russia.[133]

Migration

Most North American hummingbirds migrate southward in fall to spend winter in Mexico, the Caribbean Islands, or Central America.[134] A few southern South American species also move north to the tropics during the southern winter. A few species are year-round residents of Florida, California, and the far southwestern desert regions of the US.[134] Among these are Anna's hummingbird, a common resident from southern Arizona and inland California, and the buff-bellied hummingbird, a winter resident from Florida across the Gulf Coast to South Texas. Ruby-throated hummingbirds are common along the Atlantic flyway, and migrate in summer from as far north as Atlantic Canada,[134] returning to Mexico, South America, southern Texas, and Florida to winter.[134][135] During winter in southern Louisiana, black-chinned, buff-bellied, calliope, Allen's, Anna's, ruby-throated, rufous, broad-tailed, and broad-billed hummingbirds are present.[134]

The rufous hummingbird breeds farther north than any other species of hummingbird,[134] often breeding in large numbers in temperate North America and wintering in increasing numbers along the coasts of the subtropical Gulf of Mexico and Florida, rather than in western or central Mexico.[136] By migrating in spring as far north as the Yukon or southern Alaska,[134][136] the rufous hummingbird migrates more extensively and nests farther north than any other hummingbird species, and must tolerate occasional temperatures below freezing in its breeding territory. This cold hardiness enables it to survive temperatures below freezing, provided that adequate shelter and food are available.[136]

As calculated by displacement of body size, the rufous hummingbird makes perhaps the longest migratory journey of any bird in the world. At just over 3 in long, rufous birds travel 3,900 miles one-way from Alaska to Mexico in late summer, a distance equal to 78,470,000 body lengths.[136] By comparison, the 13-inch-long Arctic tern makes a one-way flight of about 11,185 miles, or 51,430,000 body lengths, just 65% of the body displacement during migration by rufous hummingbirds.[136]

The northward migration of rufous hummingbirds occurs along the Pacific flyway[136] and may be time-coordinated with flower and tree-leaf emergence in spring in early March, and also with availability of insects as food.[137] Arrival at breeding grounds before nectar availability from mature flowers may jeopardize breeding opportunities.[138]

Diet and specializations for food gathering

For nutrition, hummingbirds eat a variety of insects, including mosquitoes, fruit flies, gnats in flight, or aphids on leaves and spiders in their webs.[139][140][141][142] The lower beak of hummingbirds is flexible and can bend as much as 25 degrees when it widens at the base, making a larger surface for catching insects.[141] Hummingbirds hover within insect swarms in a method called "hover-hawking" to facilitate feeding.[142]

To supply energy needs, hummingbirds drink nectar, a sweet liquid inside certain flowers. Like bees, they are able to assess the amount of sugar in the nectar they drink; they normally reject flower types that produce nectar that is less than 10% sugar and prefer those whose sugar content is higher. Nectar is a mixture of glucose, fructose, and sucrose, and is a poor source of other nutrients, requiring hummingbirds to meet their nutritional needs by consuming insects.[141][142]

Hummingbirds do not spend all day flying, as the energy cost would be prohibitive; the majority of their activity consists simply of sitting or perching. Hummingbirds eat many small meals and consume around half their weight in nectar (twice their weight in nectar, if the nectar is 25% sugar) each day.[143] Hummingbirds digest their food rapidly due to their small size and high metabolism; a mean retention time less than an hour has been reported.[144] Hummingbirds spend an average of 10–15% of their time feeding and 75–80% sitting and digesting.

Because their high metabolism makes them vulnerable to starvation, hummingbirds are highly attuned to food sources. Some species, including many found in North America, are territorial and try to guard food sources (such as a feeder) against other hummingbirds, attempting to ensure a future food supply for itself. Additionally, hummingbirds have an enlarged hippocampus, a brain region facilitating spatial memory used to map flowers previously visited during nectar foraging.[145]

Hummingbird beaks are flexible[141] and their shapes vary dramatically as an adaptation for specialized feeding.[29][30] Some species, such as hermits (Phaethornis spp.) have long bills that allow them to probe deep into flowers with long corollae. Thornbills have short, sharp bills adapted for feeding from flowers with short corollae and piercing the bases of longer ones. The sicklebills' extremely decurved bills are adapted to extracting nectar from the curved corollae of flowers in the family Gesneriaceae. The bill of the fiery-tailed awlbill has an upturned tip, as in the avocets. The male tooth-billed hummingbird has barracuda-like spikes at the tip of its long, straight bill.

The two halves of a hummingbird's bill have a pronounced overlap, with the lower half (mandible) fitting tightly inside the upper half (maxilla). When a hummingbird feeds on nectar, the bill is usually opened only slightly, allowing the tongue to dart out and into the interior of flowers. Hummingbird bill sizes range from about 5 mm to as long as 100 mm (about 4 in).[146] When catching insects in flight, a hummingbird's jaw flexes downward to widen the gape for successful capture.[140]

Perception of sweet nectar

Perception of sweetness in nectar evolved in hummingbirds during their genetic divergence from insectivorous swifts, their closest bird relatives.[147] Although the only known sweet sensory receptor, called T1R2,[148] is absent in birds, receptor expression studies showed that hummingbirds adapted a carbohydrate receptor from the T1R1-T1R3 receptor, identical to the one perceived as umami in humans, essentially repurposing it to function as a nectar sweetness receptor.[147] This adaptation for taste enabled hummingbirds to detect and exploit sweet nectar as an energy source, facilitating their distribution across geographical regions where nectar-bearing flowers are available.[147]

Tongue as a micropump

Hummingbirds drink with their long tongues by rapidly lapping nectar. Their tongues have semicircular tubes which run down their lengths to facilitate nectar consumption via rapid pumping in and out of the nectar.[149][150] While capillary action was believed to be what drew nectar into these tubes,[151] high-speed photography revealed that the tubes open down their sides as the tongue goes into the nectar, and then close around the nectar, trapping it so it can be pulled back into the beak over a period of 14 milliseconds per lick at a rate of up to 20 licks per second.[152][153] The tongue, which is forked, is compressed until it reaches nectar, then the tongue springs open, the rapid action traps the nectar and the nectar moves up the grooves, like a pump action, with capillary action not involved.[149][150][153][154] Consequently, tongue flexibility enables accessing, transporting and unloading nectar via pump action,[149][150] not by a capillary syphon as once believed.[151]

Feeders and artificial nectar

In the wild, hummingbirds visit flowers for food, extracting nectar, which is 55% sucrose, 24% glucose, and 21% fructose on a dry-matter basis.[155] Hummingbirds also take sugar-water from bird feeders, which allow people to observe and enjoy hummingbirds up close while providing the birds with a reliable source of energy, especially when flower blossoms are less abundant. A negative aspect of artificial feeders, however, is that the birds may seek less flower nectar for food, and so may reduce the amount of pollination their feeding naturally provides.[156]

White granulated sugar is used in hummingbird feeders in a 20% concentration as a common recipe,[157] although hummingbirds will defend feeders more aggressively when sugar content is at 35%, indicating preference for nectar with higher sugar content.[158] Organic and "raw" sugars contain iron, which can be harmful,[159] and brown sugar, agave syrup, molasses, and artificial sweeteners also should not be used.[160] Honey is made by bees from the nectar of flowers, but it is not good to use in feeders because when it is diluted with water, microorganisms easily grow in it, causing it to spoil rapidly.[161][162][163]

Red food dye was once thought to be a favorable ingredient for the nectar in home feeders, but it is unnecessary.[164] Commercial products sold as "instant nectar" or "hummingbird food" may also contain preservatives or artificial flavors, as well as dyes, which are unnecessary and potentially harmful.[164][165] Although some commercial products contain small amounts of nutritional additives, hummingbirds obtain all necessary nutrients from the insects they eat, rendering added nutrients unnecessary.[132]

Visual cues of foraging

Hummingbirds have exceptional visual acuity providing them with discrimination of food sources while foraging.[50] Although hummingbirds are thought to be attracted to color while seeking food, such as red flowers or artificial feeders, experiments indicate that location and flower nectar quality are the most important "beacons" for foraging.[166][167] Hummingbirds depend little on visual cues of flower color to beacon to nectar-rich locations, but rather they used surrounding landmarks to find the nectar reward.[168][169]

In at least one hummingbird species – the green-backed firecrown (Sephanoides sephaniodes) – flower colors preferred are in the red-green wavelength for the bird's visual system, providing a higher contrast than for other flower colors.[170] Further, the crown plumage of firecrown males is highly iridescent in the red wavelength range (peak at 650 nanometers), possibly providing a competitive advantage of dominance when foraging among other hummingbird species with less colorful plumage.[170] The ability to discriminate colors of flowers and plumage is enabled by a visual system having four single cone cells and a double cone screened by photoreceptor oil droplets which enhance color discrimination.[166][170]

Olfaction

While hummingbirds rely primarily on vision and hearing to assess competition from bird and insect foragers near food sources, they may also be able to detect by smell the presence in nectar of insect defensive chemicals (such as formic acid) and aggregation pheromones of foraging ants, which discourage feeding.[171]

Superficially similar species

Some species of sunbirds of Africa, southern and southeastern Asia, and Australia resemble hummingbirds in appearance and behavior, as do perhaps also the honeyeaters of Australia and Pacific islands. These two groups, however, are not related to hummingbirds, as their resemblance is due to convergent evolution.[172]

The hummingbird moth has flying and feeding characteristics similar to those of a hummingbird.[173]

In myth and culture

- Aztecs wore hummingbird talismans, both artistic representations of hummingbirds and fetishes made from actual hummingbird parts: emblematic for their vigor, energy, and propensity to do work along with their sharp beaks that symbolically mimic instruments of weaponry, bloodletting, penetration, and intimacy. Hummingbird talismans were prized as drawing sexual potency, energy, vigor, and skill at arms and warfare to the wearer.[174]

- The Aztec god of war Huitzilopochtli is often depicted as a hummingbird. It was also believed that fallen warriors would return to earth as hummingbirds and butterflies.[175] The Nahuatl word huitzil (hummingbird) is an onomatopoeic word derived from the sounds of the hummingbird's wing-beats and zooming flight.

- Likewise in part Mt. Umunhum in the Santa Cruz Mountains in Northern California is Ohlone for "Resting Place of the Hummingbird"[176]

- One of the Nazca Lines depicts a hummingbird (right).

- The Hopi and Zuni cultures have a hummingbird creation myth about a young brother and sister who are starving because drought and famine have come to the land. Their parents have left to find food, so the boy carves a piece of wood into a small bird to entertain his sister. When the girl tosses the carving into the air, the bird comes to life, turning into a hummingbird. The small bird then flies to the God of Fertility and begs for rain, and the god obliges the request, which helps the crops to grow again.[177]

- Trinidad and Tobago, known as "The land of the hummingbird," displays a hummingbird on that nation's coat of arms,[178] 1-cent coin[179] and emblem of its national airline, Caribbean Airlines (right).

- The Gibson Hummingbird is an acoustic guitar model/series produced by the Gibson Guitar Corporation.

- During the National Costume competition of the Miss Universe 2016 beauty pageant, Miss Ecuador Connie Jiménez wore a costume inspired by the hummingbirds of her land[180] that included golden wings supposed to follow the movements of her arms.[181][182] However, it accidentally got damaged during the dress rehearsal, and she appeared onstage with a broken, drooping left wing.[183][184]

See also

- AeroVironment Nano Hummingbird – artificial hummingbird

- Macroglossum stellatarum – hummingbird hawk-moth

- Hemaris – sphinx moths (hummingbird moths) confused with hummingbirds

References

- Gill, F.; Donsker, D.; Rasmussen, P. (July 2021). "IOC World Bird List (v 12.1), International Ornithological Committee". doi:10.14344/IOC.ML.11.2. Retrieved January 15, 2022.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Clark, C. J.; Dudley, R. (2009). "Flight costs of long, sexually selected tails in hummingbirds". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 276 (1664): 2109–115. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0090. PMC 2677254. PMID 19324747.

- Ridgely RS, Greenfield PG (2001). The Birds of Ecuador, Field Guide (1 ed.). Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8721-7.

- Suarez, R. K. (1992). "Hummingbird flight: Sustaining the highest mass-specific metabolic rates among vertebrates". Experientia. 48 (6): 565–570. doi:10.1007/bf01920240. PMID 1612136. S2CID 21328995.

- "Hummingbirds". Nationalzoo.si.edu. Archived from the original on July 16, 2012. Retrieved April 1, 2013.

- Vigors, Nicholas Aylward (1825). "Observations on the natural affinities that connect the orders and families of birds". Transactions of the Linnean Society of London. 14 (3): 395–517 [463]. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.1823.tb00098.x.

- Bock, Walter J. (1994). History and Nomenclature of Avian Family-Group Names. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. Vol. Number 222. New York: American Museum of Natural History. pp. 143, 264. hdl:2246/830.

- McGuire, J.A.; Witt, C.C.; Altshuler, D.L.; Remsen, J.V. (2007). "Phylogenetic systematics and biogeography of hummingbirds: Bayesian and maximum likelihood analyses of partitioned data and selection of an appropriate partitioning strategy". Systematic Biology. 56 (5): 837–856. doi:10.1080/10635150701656360. PMID 17934998.

- McGuire, J.; Witt, C.; Remsen, J.V.; Corl, A.; Rabosky, D.; Altshuler, D.; Dudley, R. (2014). "Molecular phylogenetics and the diversification of hummingbirds". Current Biology. 24 (8): 910–916. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.016. PMID 24704078.

- Dickinson, E.C.; Remsen, J.V. Jr., eds. (2013). The Howard & Moore Complete Checklist of the Birds of the World. Vol. 1: Non-passerines (4th ed.). Eastbourne, UK: Aves Press. pp. 105–136. ISBN 978-0-9568611-0-8.

- McGuire, J.A.; Witt, C.C.; Remsen, J.V.; Dudley, R.; Altshuler, D.L. (2009). "A higher-level taxonomy for hummingbirds". Journal of Ornithology. 150 (1): 155–165. doi:10.1007/s10336-008-0330-x.

- Bleiweiss, R.; Kirsch, J.A.; Matheus, J.C. (1997). "DNA hybridization evidence for the principal lineages of hummingbirds (Aves:Trochilidae)". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 14 (3): 325–343. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025767. PMID 9066799.

- Dickinson & Remsen 2013, pp. 105–136.

- Mayr, Gerald (March 2005). "Fossil hummingbirds of the Old World" (PDF). Biologist. 52 (1): 12–16. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2011. Retrieved December 14, 2009.

- Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (July 2020). "IOC World Bird List Version 10.2". International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved January 3, 2020.

- Mayr, Gerald (2004). "Old World fossil record of modern-type hummingbirds". Science. 304 (5672): 861–864. Bibcode:2004Sci...304..861M. doi:10.1126/science.1096856. PMID 15131303. S2CID 6845608.

- Bleiweiss, Robert; Kirsch, John A. W.; Matheus, Juan Carlos (1999). "DNA-DNA hybridization evidence for subfamily structure among hummingbirds" (PDF). Auk. 111 (1): 8–19. doi:10.2307/4088500.

- Ksepka, Daniel T.; Clarke, Julia A.; Nesbitt, Sterling J.; Kulp, Felicia B.; Grande, Lance (2013). "Fossil evidence of wing shape in a stem relative of swifts and hummingbirds (Aves, Pan-Apodiformes)". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 280 (1761): 1761. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.0580. PMC 3652446. PMID 23760643.

- Mayr, Gerald (January 1, 2007). "New specimens of the early Oligocene Old World hummingbird Eurotrochilus inexpectatus". Journal of Ornithology. 148 (1): 105–111. doi:10.1007/s10336-006-0108-y. ISSN 2193-7206. S2CID 11821178.

- Bochenski, Zygmunt; Bochenski, Zbigniew M. (April 1, 2008). "An Old World hummingbird from the Oligocene: a new fossil from Polish Carpathians". Journal of Ornithology. 149 (2): 211–216. doi:10.1007/s10336-007-0261-y. ISSN 2193-7206. S2CID 22193761.

- "Hummingbirds' 22-million-year-old history of remarkable change is far from complete". ScienceDaily. April 3, 2014. Retrieved September 30, 2014.

- McGuire, Jimmy A.; Witt, Christopher C.; Remsen, J. V. Jr.; Dudley, R.; Altshuler, Douglas L. (2008). "A higher-level taxonomy for hummingbirds". Journal of Ornithology. 150 (1): 155–165. doi:10.1007/s10336-008-0330-x. ISSN 0021-8375. S2CID 1918245.

- Baldwin, M. W.; Toda, Y.; Nakagita, T.; O'Connell, M. J.; Klasing, K. C.; Misaka, T.; Edwards, S. V.; Liberles, S. D. (2014). "Evolution of sweet taste perception in hummingbirds by transformation of the ancestral umami receptor". Science. 345 (6199): 929–933. Bibcode:2014Sci...345..929B. doi:10.1126/science.1255097. PMC 4302410. PMID 25146290.

- Abrahamczyk S, Renner SS (2015). "The temporal build-up of hummingbird/plant mutualisms in North America and temperate South America". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 15: 104. doi:10.1186/s12862-015-0388-z. PMC 4460853. PMID 26058608.

- Abrahamczyk S, Souto-Vilarós D, McGuire JA, Renner SS (2015). "Diversity and clade ages of West Indian hummingbirds and the largest plant clades dependent on them: a 5–9 Myr young mutualistic system". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 114 (4): 848–859. doi:10.1111/bij.12476.

- Abrahamczyk, S.; Souto-Vilaros, D.; Renner, S. S. (2014). "Escape from extreme specialization: Passionflowers, bats and the sword-billed hummingbird". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 281 (1795): 20140888. doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.0888. PMC 4213610. PMID 25274372.

- Colwell, Robert K. (November 1, 2000). "Rensch's Rule Crosses the Line: Convergent Allometry of Sexual Size Dimorphism in Hummingbirds and Flower Mites". The American Naturalist. 156 (5): 495–510. doi:10.1086/303406. PMID 29587514. S2CID 4401233.

- Lisle, Stephen P. De; Rowe, Locke (November 1, 2013). "Correlated Evolution of Allometry and Sexual Dimorphism across Higher Taxa". The American Naturalist. 182 (5): 630–639. doi:10.1086/673282. PMID 24107370. S2CID 25612107.

- Berns, Chelsea M.; Adams, Dean C. (November 11, 2012). "Becoming Different But Staying Alike: Patterns of Sexual Size and Shape Dimorphism in Bills of Hummingbirds". Evolutionary Biology. 40 (2): 246–260. doi:10.1007/s11692-012-9206-3. ISSN 0071-3260. S2CID 276492.

- Temeles, Ethan J.; Miller, Jill S.; Rifkin, Joanna L. (April 12, 2010). "Evolution of sexual dimorphism in bill size and shape of hermit hummingbirds (Phaethornithinae): a role for ecological causation". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 365 (1543): 1053–063. doi:10.1098/rstb.2009.0284. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 2830232. PMID 20194168.

- Stiles, Gary (1981). "Geographical aspects of bird flower coevolution, with particular reference to Central America" (PDF). Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden. 68 (2): 323–351. doi:10.2307/2398801. S2CID 87692272.

- Maglianesi, M.A.; Blüthgen, N.; Böhning-Gaese, K. & Schleuning, M. (2014). "Morphological traits determine specialization and resource use in plant–hummingbird networks in the Neotropics". Ecology. 95 (12): 3325–334. doi:10.1890/13-2261.1.

- Abrahamczyk, Stefan; Poretschkin, Constantin & Renner, Susanne S. (2017). "Evolutionary flexibility in five hummingbird/plant mutualistic systems: testing temporal and geographic matching". Journal of Biogeography. 44 (8): 1847–855. doi:10.1111/jbi.12962. S2CID 90399556.

- Simon, Matt (July 10, 2015). "Absurd Creature of the Week: The World's Tiniest Bird Weighs Less Than a Dime". Wired. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- Dalsgaard, B; Martín González, A. M.; Olesen, J. M.; Ollerton, J; Timmermann, A; Andersen, L. H. & Tossas, A. G. (2009). "Plant-hummingbird interactions in the West Indies: Floral specialisation gradients associated with environment and hummingbird size". Oecologia. 159 (4): 757–766. Bibcode:2009Oecol.159..757D. doi:10.1007/s00442-008-1255-z. PMID 19132403. S2CID 35922888.

- Rodríguez-Gironés, M. A. & Santamaría, L. (2004). "Why are so many bird flowers red?". PLOS Biology. 2 (10): e350. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020350. PMC 521733. PMID 15486585.

- Altschuler, D. L. (2003). "Flower color, hummingbird pollination, and habitat irradiance in four Neotropical forests". Biotropica. 35 (3): 344–355. doi:10.1646/02113. S2CID 55929111.

- Nicolson, S. W. & Fleming, P. A. (2003). "Nectar as food for birds: the physiological consequences of drinking dilute sugar solutions". Plant Systematics and Evolution. 238 (1–4): 139–153. doi:10.1007/s00606-003-0276-7. S2CID 23401164.

- Junker, Robert R.; Blüthgen, Nico; Brehm, Tanja; Binkenstein, Julia; Paulus, Justina; Martin Schaefer, H. & Stang, Martina (December 13, 2012). "Specialization on traits as basis for the niche‐breadth of flower visitors and as structuring mechanism of ecological networks". Functional Ecology. 27 (2): 329–341. doi:10.1111/1365-2435.12005.

- Martín González, Ana M.; Dalsgaard, Bo; et al. (July 30, 2015). "The macroecology of phylogenetically structured hummingbird-plant networks". Global Ecology and Biogeography. 24 (11): 1212–224. doi:10.1111/geb.12355. hdl:10026.1/3407.

- Rico-Guevara A, Araya-Salas M (2015). "Bills as daggers? A test for sexually dimorphic weapons in a lekking hummingbird". Behavioral Ecology. 26 (1): 21–29. doi:10.1093/beheco/aru182.

- Hightower, Ben J; Wijnings, Patrick WA; Scholte, Rick; Ingersoll, Rivers; Chin, Diana D; Nguyen, Jade; Shorr, Daniel; Lentink, David (March 16, 2021). "How oscillating aerodynamic forces explain the timbre of the hummingbird's hum and other animals in flapping flight". eLife. 10: e63107. doi:10.7554/elife.63107. ISSN 2050-084X. PMC 8055270. PMID 33724182.

- Eindhoven University of Technology (March 16, 2021). "New measurement technique unravels what gives hummingbird wings their characteristic sound". Phys.org. Retrieved May 13, 2021.

- Ingersoll, Rivers; Lentink, David (October 15, 2018). "How the hummingbird wingbeat is tuned for efficient hovering". Journal of Experimental Biology. 221 (20). doi:10.1242/jeb.178228. ISSN 1477-9145. PMID 30323114.

- Steen, Ronny; Kagge, Erik Olfert; Lilleengen, Petter; Lindemann, Jon Peder; Midtgaard, Fred (2020). "Wingbeat frequencies in free-ranging hummingbirds in Costa Rica and Ecuador". Cotinga. 42: 3–8.

- Clark, C. J. (2011). "Wing, tail, and vocal contributions to the complex acoustic signals of courting Calliope hummingbirds". Current Zool. 57 (2): 187–196. doi:10.1093/czoolo/57.2.187.

- Ravi S, Crall JD, McNeilly L, Gagliardi SF, Biewener AA, Combes SA (2015). "Hummingbird flight stability and control in freestream turbulent winds". J Exp Biol. 218 (Pt 9): 1444–452. doi:10.1242/jeb.114553. PMID 25767146.

- Goller B, Altshuler DL (2014). "Hummingbirds control hovering flight by stabilizing visual motion". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (51): 18375–380. Bibcode:2014PNAS..11118375G. doi:10.1073/pnas.1415975111. PMC 4280641. PMID 25489117.

- Ocampo, Diego; Barrantes, Gilbert; Uy, J. Albert C. (September 27, 2018). "Morphological adaptations for relatively larger brains in hummingbird skulls". Ecology and Evolution. 8 (21): 10482–10488. doi:10.1002/ece3.4513. ISSN 2045-7758. PMC 6238128. PMID 30464820.

- Lisney TJ, Wylie DR, Kolominsky J, Iwaniuk AN (2015). "Eye morphology and retinal topography in hummingbirds (Trochilidae Aves)". Brain, Behavior and Evolution. 86 (3–4): 176–190. doi:10.1159/000441834. PMID 26587582.

- Iwaniuk AN, Wylie DR (2007). "Neural specialization for hovering in hummingbirds: hypertrophy of the pretectal nucleus Lentiformis mesencephali" (PDF). Journal of Comparative Neurology. 500 (2): 211–221. doi:10.1002/cne.21098. PMID 17111358. S2CID 15678218.

- Gaede, A. H.; Goller, B; Lam, J. P.; Wylie, D. R.; Altshuler, D. L. (2017). "Neurons responsive to global visual motion have unique tuning properties in hummingbirds". Current Biology. 27 (2): 279–285. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.11.041. PMID 28065606. S2CID 28314419.

- "Hummingbirds see motion in an unexpected way". ScienceDaily. January 5, 2017. Retrieved April 24, 2017.

- Stoddard, Mary Caswell; Eyster, Harold N.; Hogan, Benedict G.; Morris, Dylan H.; Soucy, Edward R.; Inouye, David W (June 15, 2020). "Wild hummingbirds discriminate nonspectral colors". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 117 (26): 15112–122. doi:10.1073/pnas.1919377117. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 7334476. PMID 32541035.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Altshuler, D. L.; Dudley, R (2002). "The ecological and evolutionary interface of hummingbird flight physiology". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 205 (Pt 16): 2325–336. doi:10.1242/jeb.205.16.2325. PMID 12124359.

- Lasiewski, Robert C. (1964). "Body temperatures, heart and breathing rate, and evaporative water loss in hummingbirds". Physiological Zoology. 37 (2): 212–223. doi:10.1086/physzool.37.2.30152332. S2CID 87037075.

- Hargrove, J. L. (2005). "Adipose energy stores, physical work, and the metabolic syndrome: Lessons from hummingbirds". Nutrition Journal. 4: 36. doi:10.1186/1475-2891-4-36. PMC 1325055. PMID 16351726.

- Welch, K. C. Jr.; Chen, C. C. (2014). "Sugar flux through the flight muscles of hovering vertebrate nectarivores: A review". Journal of Comparative Physiology B. 184 (8): 945–959. doi:10.1007/s00360-014-0843-y. PMID 25031038. S2CID 11109453.

- Chen, Chris Chin Wah; Welch, Kenneth Collins (2014). "Hummingbirds can fuel expensive hovering flight completely with either exogenous glucose or fructose". Functional Ecology. 28 (3): 589–600. doi:10.1111/1365-2435.12202.

- Welch, K. C. Jr.; Suarez, R. K. (2007). "Oxidation rate and turnover of ingested sugar in hovering Anna's (Calypte anna) and rufous (Selasphorus rufus) hummingbirds". Journal of Experimental Biology. 210 (Pt 12): 2154–162. doi:10.1242/jeb.005363. PMID 17562889.

- Suarez, Raul; Welch, Kenneth (July 12, 2017). "Sugar metabolism in hummingbirds and nectar bats". Nutrients. 9 (7): 743. doi:10.3390/nu9070743. ISSN 2072-6643. PMC 5537857. PMID 28704953.

- Skutch, Alexander F. & Singer, Arthur B. (1973). The Life of the Hummingbird. New York: Crown Publishers. ISBN 978-0-517-50572-4.

- Projecto-Garcia, Joana; Natarajan, Chandrasekhar; Moriyama, Hideaki; et al. (December 2, 2013). "Repeated elevational transitions in hemoglobin function during the evolution of Andean hummingbirds". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110 (51): 20669–20674. Bibcode:2013PNAS..11020669P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1315456110. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3870697. PMID 24297909.

- "How do hummingbirds thrive in the Andes?". The Guardian. December 13, 2013. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- Lim, Marisa C W; Witt, Christopher C; Graham, Catherine H; Dávalos, Liliana M (May 22, 2019). "Parallel molecular evolution in pathways, genes, and sites in high-elevation hummingbirds revealed by comparative transcriptomics". Genome Biology and Evolution. 11 (6): 1573–1585. doi:10.1093/gbe/evz101. ISSN 1759-6653. PMC 6553505. PMID 31114863.

- Deann Gayman (December 2, 2013). "New study reveals how hummingbirds evolved to fly at high altitude". Department of Communication and Marketing, University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- Powers, Donald R.; Langland, Kathleen M.; Wethington, Susan M.; Powers, Sean D.; Graham, Catherine H.; Tobalske, Bret W. (2017). "Hovering in the heat: effects of environmental temperature on heat regulation in foraging hummingbirds". Royal Society Open Science. 4 (12): 171056. doi:10.1098/rsos.171056. ISSN 2054-5703. PMC 5750011. PMID 29308244.

- Evangelista, Dennis; Fernández, María José; Berns, Madalyn S.; Hoover, Aaron; Dudley, Robert (2010). "Hovering energetics and thermal balance in Anna's hummingbirds (Calypte anna)". Physiological and Biochemical Zoology. 83 (3): 406–413. doi:10.1086/651460. ISSN 1522-2152. PMID 20350142. S2CID 26974159.

- Matt Soniak (February 2, 2016). "Infrared video shows how hummingbirds shed heat through their eyes and feet". Mental Floss. Retrieved January 14, 2020.

- Miklos D F Udvardy (1983). "The role of the feet in behavioral thermoregulation of hummingbirds" (PDF). Condor. 85 (3): 281–285. doi:10.2307/1367060.

- Suarez, R. K.; Gass, C. L. (2002). "Hummingbirds foraging and the relation between bioenergetics and behavior". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. Part A. 133 (2): 335–343. doi:10.1016/S1095-6433(02)00165-4. PMID 12208304.

- Bakken, B. H.; McWhorter, T. J.; Tsahar, E.; Martinez del Rio, C. (2004). "Hummingbirds arrest their kidneys at night: diel variation in glomerular filtration rate in Selasphorus platycercus". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 207 (25): 4383–391. doi:10.1242/jeb.01238. PMID 15557024.

- Bakken, BH; Sabat, P (2006). "Gastrointestinal and renal responses to water intake in the green-backed firecrown (Sephanoides sephanoides), a South American hummingbird". AJP: Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 291 (3): R830–836. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00137.2006. hdl:10533/177203. PMID 16614056. S2CID 2391784.

- Lotz, Chris N.; Martínez Del Rio, Carlos (2004). "The ability of rufous hummingbirds Selasphorus rufus to dilute and concentrate urine". Journal of Avian Biology. 35: 54–62. doi:10.1111/j.0908-8857.2004.03083.x.

- Beuchat CA, Preest MR, Braun EJ (1999). "Glomerular and medullary architecture in the kidney of Anna's Hummingbird". Journal of Morphology. 240 (2): 95–100. doi:10.1002/(sici)1097-4687(199905)240:2<95::aid-jmor1>3.0.co;2-u. PMID 29847878. S2CID 44156688.

- "Song sounds of various hummingbird species". All About Birds. The Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY. 2015. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- Jarvis ED, Ribeiro S, da Silva ML, Ventura D, Vielliard J, Mello CV (2000). "Behaviourally driven gene expression reveals song nuclei in hummingbird brain". Nature. 406 (6796): 628–632. Bibcode:2000Natur.406..628J. doi:10.1038/35020570. PMC 2531203. PMID 10949303.

- Gahr M (2000). "Neural song control system of hummingbirds: comparison to swifts, vocal learning (Songbirds) and nonlearning (Suboscines) passerines, and vocal learning (Budgerigars) and nonlearning (Dove, owl, gull, quail, chicken) nonpasserines". J Comp Neurol. 486 (2): 182–196. doi:10.1002/1096-9861(20001016)426:2<182::AID-CNE2>3.0.CO;2-M. PMID 10982462. S2CID 10763166.

- Renne, Paul R.; Deino, Alan L.; Hilgen, Frederik J.; Kuiper, Klaudia F.; Mark, Darren F.; Mitchell, William S.; Morgan, Leah E.; Mundil, Roland; Smit, Jan (February 7, 2013). "Time Scales of Critical Events Around the Cretaceous-Paleogene Boundary" (PDF). Science. 339 (6120): 684–687. Bibcode:2013Sci...339..684R. doi:10.1126/science.1230492. PMID 23393261. S2CID 6112274. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 7, 2017. Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- Pytte, C. L.; Ficken, M. S.; Moiseff, A (2004). "Ultrasonic singing by the blue-throated hummingbird: A comparison between production and perception". Journal of Comparative Physiology A. 190 (8): 665–673. doi:10.1007/s00359-004-0525-4. PMID 15164219. S2CID 7231117.

- Monte, Amanda; Cerwenka, Alexander F.; Ruthensteiner, Bernhard; Gahr, Manfred; Düring, Daniel N. (July 6, 2020). "The hummingbird syrinx morphome: a detailed three-dimensional description of the black jacobin's vocal organ". BMC Zoology. 5 (1): 7. doi:10.1186/s40850-020-00057-3. ISSN 2056-3132. S2CID 220509046.

- Riede, Tobias; Olson, Christopher R. (February 6, 2020). "The vocal organ of hummingbirds shows convergence with songbirds". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 2007. Bibcode:2020NatSR..10.2007R. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-58843-5. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 7005288. PMID 32029812.

- Hainsworth, F. R.; Wolf, L. L. (1970). "Regulation of oxygen consumption and body temperature during torpor in a hummingbird, Eulampis jugularis". Science. 168 (3929): 368–369. Bibcode:1970Sci...168..368R. doi:10.1126/science.168.3929.368. PMID 5435893. S2CID 30793291.

- Hiebert, S. M. (1992). "Time-dependent thresholds for torpor initiation in the rufous hummingbird (Selasphorus rufus)". Journal of Comparative Physiology B. 162 (3): 249–255. doi:10.1007/bf00357531. PMID 1613163. S2CID 24688360.

- Wolf, Blair O.; McKechnie, Andrew E.; Schmitt, C. Jonathan; Czenze, Zenon J.; Johnson, Andrew B.; Witt, Christopher C. (2020). "Extreme and variable torpor among high-elevation Andean hummingbird species". Biology Letters of the Royal Society. 16 (9): 20200428. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2020.0428. ISSN 1744-9561. PMC 7532710. PMID 32898456.

- Greenwood, Veronique (September 8, 2020). "These hummingbirds take extreme naps. Some may even hibernate". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 9, 2020.

- Hiebert, S. M.; Salvante, K. G.; Ramenofsky, M; Wingfield, J. C. (2000). "Corticosterone and nocturnal torpor in the rufous hummingbird (Selasphorus rufus)". General and Comparative Endocrinology. 120 (2): 220–234. doi:10.1006/gcen.2000.7555. PMID 11078633.

- Powers, D. R.; Brown, A. R.; Van Hook, J. A. (2003). "Influence of normal daytime fat deposition on laboratory measurements of torpor use in territorial versus nonterritorial hummingbirds". Physiological and Biochemical Zoology. 76 (3): 389–397. doi:10.1086/374286. PMID 12905125. S2CID 6475160.

- Shankar, Anusha; Schroeder, Rebecca J.; Wethington, Susan M.; Graham, Catherine H.; Powers, Donald R. (May 2020). "Hummingbird torpor in context: duration, more than temperature, is the key to nighttime energy savings". Journal of Avian Biology. 51 (5): jav.02305. doi:10.1111/jav.02305. ISSN 0908-8857. S2CID 216458501.

- "The hummingbird project of British Columbia". Rocky Point Bird Observatory, Vancouver Island, British Columbia. 2010. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- Churchfield, Sara. (1990). The natural history of shrews. Cornell University Press. pp. 35–37. ISBN 978-0-8014-2595-0.

- "Longevity Records Of North American Birds". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Bird Banding Laboratory. Longevity Records AOU Numbers 3930–4920 2009-08-31. Retrieved 2009-09-27.

- Fisher, R. Jr. (1994). "Praying mantis catches and eats hummingbird". Birding. 26: 376.

- Lorenz, S. (2007). "Carolina mantid (Stagmomantis carolina) captures and feeds on a broad-tailed hummingbird (Selasphorus platycercus)". Bulletin of the Texas Ornithological Society. 40: 37–38.

- Nyffeler, Martin; Maxwell, Michael R.; Remsen, J. V. (2017). "Bird predation by praying mantises: A global perspective". The Wilson Journal of Ornithology. 129 (2): 331–344. doi:10.1676/16-100.1. ISSN 1559-4491. S2CID 90832425.

- Sharon Stiteler (October 29, 2015). "Which animals prey on hummingbirds?". National Audubon Society. Retrieved November 4, 2021.

- Oniki, Y; Willis, E. O. (2000). "Nesting behavior of the swallow-tailed hummingbird, Eupetomena macroura (Trochilidae, Aves)". Brazilian Journal of Biology. 60 (4): 655–662. doi:10.1590/s0034-71082000000400016. PMID 11241965.

- "Hummingbird nesting". Public Broadcasting System – Nature; from Learner.org, Journey North. 2016. Archived from the original (video) on February 2, 2017. Retrieved May 12, 2016.

- Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Hummingbird nesting and fledgling" (video). 2011. Retrieved May 12, 2016 – via YouTube.

- "Hummingbird Q&A: Nest and eggs". Operation Rubythroat: the Hummingbird Project, Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History. 2014. Retrieved June 21, 2014.

- Mohrman, Eric (November 22, 2019). "How do hummingbirds mate?". Sciencing, Leaf Group Media. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

- "Hummingbird characteristics". learner.org. Annenberg Learner, The Annenberg Foundation. 2015. Archived from the original on November 11, 2016. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- Williamson S (2001). A Field Guide to Hummingbirds of North America. Section: Plumage and Molt. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 13–18. ISBN 978-0-618-02496-4.

- Hamilton WJ (1965). "Sun-oriented display of the Anna's hummingbird" (PDF). The Wilson Bulletin. 77 (1).

- Meadows MG, Roudybush TE, McGraw KJ (2012). "Dietary protein level affects iridescent coloration in Anna's hummingbirds, Calypte anna". J Exp Biol. 215 (16): 2742–750. doi:10.1242/jeb.069351. PMC 3404802. PMID 22837446.

- Rayner, J.M.V. (1995). "Dynamics of vortex wakes of flying and swimming vertebrates". Symp. Soc. Exp. Biol. 49: 131–155. PMID 8571221.

- Warrick DR, Tobalske BW, Powers DR (2005). "Aerodynamics of the hovering hummingbird". Nature. 435 (7045): 1094–097. Bibcode:2005Natur.435.1094W. doi:10.1038/nature03647. PMID 15973407. S2CID 4427424.

- Sapir, N; Dudley, R (2012). "Backward flight in hummingbirds employs unique kinematic adjustments and entails low metabolic cost". Journal of Experimental Biology. 215 (Pt 20): 3603–611. doi:10.1242/jeb.073114. PMID 23014570.

- Tobalske BW, Warrick DR, Clark CJ, Powers DR, Hedrick TL, Hyder GA, Biewener AA (2007). "Three-dimensional kinematics of hummingbird flight". J Exp Biol. 210 (13): 2368–382. doi:10.1242/jeb.005686. PMID 17575042.

- Tobalske, B. W.; Biewener, A. A.; Warrick, D. R.; Hedrick, T. L.; Powers, D. R. (2010). "Effects of flight speed upon muscle activity in hummingbirds". Journal of Experimental Biology. 213 (Pt 14): 2515–523. doi:10.1242/jeb.043844. PMID 20581281.

- Videler JJ (2005). Avian Flight. Oxford University Press, Ornithology Series. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-19-856603-8.

- Fernández, M. J.; Dudley, R; Bozinovic, F (2011). "Comparative energetics of the giant hummingbird (Patagona gigas)". Physiological and Biochemical Zoology. 84 (3): 333–340. doi:10.1086/660084. PMID 21527824. S2CID 31616893.

- Gill V (July 30, 2014). "Hummingbirds edge out helicopters in hover contest". BBC News. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- Feinsinger, Peter; Colwell, Robert K.; Terborgh, John; Chaplin, Susan Budd (1979). "Elevation and the Morphology, Flight Energetics, and Foraging Ecology of Tropical Hummingbirds". The American Naturalist. 113 (4): 481–497. doi:10.1086/283408. ISSN 0003-0147. S2CID 85317341.

- Morelle R (November 8, 2011). "Hummingbirds shake their heads to deal with rain". BBC News. Retrieved March 22, 2014.

- St. Fleur N (July 20, 2012). "Hummingbird rain trick: New study shows tiny birds alter posture in storms" (video). Huffington Post. Retrieved March 22, 2014.

- Clark, C. J. (2009). "Courtship dives of Anna's hummingbird offer insights into flight performance limits". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 276 (1670): 3047–052. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0508. PMC 2817121. PMID 19515669.

- Akparibo, Issaka Y.; Anderson, Jackie; Chumbley, Eric (September 7, 2020). "Aerospace Gravitational Effects". Aerospace, gravitational effects, high performance. National Center for Biotechnology Information, US National Institute of Medicine. PMID 28613519.

- Clark, C. J.; Feo, T. J. (2008). "The Anna's hummingbird chirps with its tail: A new mechanism of sonation in birds". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 275 (1637): 955–962. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.1619. PMC 2599939. PMID 18230592.

- Clark CJ (2014). "Harmonic hopping, and both punctuated and gradual evolution of acoustic characters in Selasphorus hummingbird tail-feathers". PLOS ONE. 9 (4): e93829. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...993829C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0093829. PMC 3983109. PMID 24722049.

- Clark, C. J.; Feo, T. J. (2010). "Why do Calypte hummingbirds "sing" with both their tail and their syrinx? An apparent example of sexual sensory bias". The American Naturalist. 175 (1): 27–37. doi:10.1086/648560. PMID 19916787. S2CID 29680714.