Izanami

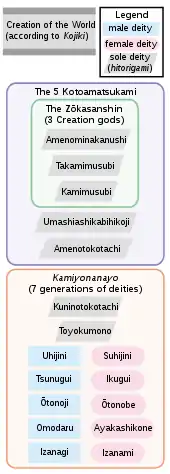

Izanami (イザナミ), formally known as Izanami-no-Mikoto (伊弉冉尊/伊邪那美命, meaning "She-who-invites" or the "Female-who-invites"), is the creator deity of both creation and death in Japanese mythology, as well as the Shinto mother goddess. She and her brother-husband Izanagi are the last of the seven generations of primordial deities that manifested after the formation of heaven and earth. Izanami and Izanagi are held to be the creators of the Japanese archipelago and the progenitors of many deities, which include the sun goddess Amaterasu, the moon deity Tsukuyomi and the storm god Susanoo.

| Part of a series on |

| Shinto |

|---|

|

| Izanami-no-Mikoto | |

|---|---|

Primordial goddess of creation and death | |

Searching the Seas with the Tenkei (天瓊を以て滄海を探るの図, Tenkei o motte sōkai o saguru no zu). Painting by Kobayashi Eitaku, 1880-90 (MFA, Boston). Izanagi with the spear Amenonuhoko to the right, Izanami to the left. | |

| Other names | Izanami-no-Kami (伊弉冉神) |

| Japanese | 伊邪那美 |

| Major cult center | Taga Taisha |

| Texts | Kojiki, Nihon Shoki, Sendai Kuji Hongi |

| Gender | Female |

| Region | Japan |

| Personal information | |

| Parents | None (Kojiki, Nihon Shoki) Aokashikine-no-Mikoto (Shoki) Awanagi-no-Mikoto (Shoki) Omodaru and Ayakashikone.[1] |

| Siblings | Izanagi |

| Consort | Izanagi |

| Children | Amaterasu Tsukuyomi Susanoo Hiruko Kagu-tsuchi (and others) |

Name

Her name is given in the Kojiki (ca. 712 AD) both as Izanami-no-Kami (伊弉冉神) and Izanami-no-Mikoto (伊弉冉尊), while the Nihon Shoki (720 AD) refers to her as Izanami-no-Mikoto, with the name written in different characters (伊邪那美命).

The names Izanagi (Izanaki) and Izanami are often interpreted as being derived from the verb izanau (historical orthography izanafu) or iⁿzanap- from Western Old Japanese 'to invite' , with -ki / -gi and -mi being taken as masculine and feminine suffixes, respectively.[2][3][4] The literal translation of Iⁿzanaŋgî and Iⁿzanamî are 'Male-who-invites' and 'Female-who-invites'.[5][6] Shiratori Kurakichi proposed an alternative theory which instead sees the root iza- (or rather isa-) to be derived from isao (historical orthography: isawo) meaning 'achievement' or 'merit'.[7]

The etymological origin of the verb is suggested to be a precursor to the Middle Korean lemma yènc- meaning 'to place/put on [the top of]' reconstructed as *yenc-a (place-INF) in OK.[8] This does coincide with other related mythological figures related to a source in the Korean peninsula like Susanöwo.

Goddess of creation

The first gods Kunitokotachi and Amenominakanushi summoned two divine beings into existence, the male Izanagi and the female Izanami, and charged them with creating the first land. To help them do this, Izanagi and Izanami were given a spear decorated with jewels, named Amenonuhoko (heavenly spear). The two deities then went to the bridge between heaven and earth, Ame-no-ukihashi ("floating bridge of heaven"), and churned the sea below with the spear. When drops of salty water fell from the spear, Onogoroshima was created. They descended from the bridge of heaven and made their home on the island.[9]

Eventually they wished to be mated, so they built a pillar called Ame-no-mihashira ("pillar of heaven"; the mi- is an honorific prefix) and around it they built a palace called Yahiro-dono (one hiro is approximately 1.82 m, so the "eight-hiro-palace" would have been 14.56 m). Izanagi and Izanami circled the pillar in opposite directions and, when they met on the other side, Izanami spoke first in greeting. Izanagi did not think that this was proper, but they mated anyhow. They had two children, Hiruko ("leech-child"), who later came to be known in Shintoism as the god Ebisu,[10] and Awashima, but they were born deformed and were not considered deities.

They put the children into a boat and set them out to sea, then petitioned the other gods for an answer as to what they did wrong. They were told that the male deity should have spoken first in greeting during the marriage ceremony. So Izanagi and Izanami went around the pillar again, this time Izanagi speaking first when they met, and their marriage was finally successful.

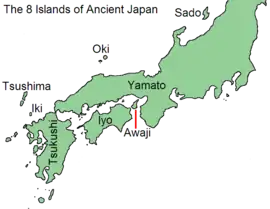

From their union were born the Ōyashima, or the "great eight islands" of the Japanese chain:

They bore six more islands and many deities. Izanami died giving birth to the child Kagu-tsuchi (incarnation of fire) or Ho-Musubi (causer of fire).[10] She was then buried on Mt. Hiba, at the border of the old provinces of Izumo and Hōki, near modern-day Yasugi of Shimane Prefecture. Izanagi was so angry at the death of his wife that he killed the newborn child, thereby creating dozens of deities.

In the Kojiki

The Kojiki talks of the death of Izanami and her tomb, which was located at the boundary between country Izumo and Hōki. It implies that Izanami transferred her soul to an animal and a human before her death, but does not state whether or not Izanami had incarnations.[11]

Death and the underworld

Izanagi-no-Mikoto lamented the death of Izanami-no-Mikoto and undertook a journey to Yomi ("the shadowy land of the dead"). He searched for Izanami-no-Mikoto and found her. At first, Izanagi-no-Mikoto could not see her for the shadows hid her appearance. He asked her to return with him. Izanami-no-Mikoto informed Izanagi-no-Mikoto that he was too late. She had already eaten the food of the underworld and was now one with the land of the dead. She could no longer return to the living but would try to ask for permission to leave.[12]

The news shocked Izanagi-no-Mikoto, but he refused to leave her in Yomi. While Izanami-no-Mikoto was sleeping, he took the comb that bound his long hair and set it alight as a torch. Under the sudden burst of light, he saw the horrid form of the once beautiful and graceful Izanami-no-Mikoto. She was now a rotting form of flesh with maggots and foul creatures running over her ravaged body.

Crying out loud, Izanagi-no-Mikoto could no longer control his fear and started to run, intending to return to the living and abandon his death-ridden wife. Izanami-no-Mikoto woke up, shrieking and indignant, and chased after him. She also sent Yakusa-no-ikazuchi-no-kami (Raijin) and shikome (foul women) to hunt for Izanagi-no-Mikoto and bring him back to Yomi.

Izanagi-no-Mikoto burst out of the entrance and pushed a boulder in the mouth of the Yomotsuhirasaka (黄泉津平坂; cavern that was the entrance of Yomi) to create a separation between the world of the living and the world of the dead, as well as separating Izanagi from Izanami.[12]

Izanami-no-Mikoto screamed from behind this impenetrable barricade and told Izanagi-no-Mikoto that if he left her she would destroy 1,000 residents of the living every day. He furiously replied he would give life to 1,500 residents.

Izanagi is said to have performed ritualistic cleansing, harai, after witnessing the decomposing body of his wife. This is the traditional explanation for the purification rituals often performed at Shinto shrines in Japanese religion, where shrine-goers wash themselves with water before entering the sacred space.[13] While he bathed, Izanagi gave birth to the sun goddess, Amaterasu, from his left eye, the moon god, Tsukuyomi, from his right eye, and the storm god, Susanoo, from his nose.[10]

In the Nihonshoki

While similar in many aspects, the version of the tale of Izanagi and Izanami in the Nihonshoki differs from the Kojiki version in that Izanagi does not descend into the Underworld (Yomi), instead residing permanently on the island of Awaji in a temple. Additionally, in the Nihonshoki, the three deities Amaterasu, Tsukiyomi, and Susanoo were said to have been created by both Izanagi and Izanami, instead of Izanagi alone.[14]

See also

- Twins in mythology

- Shinto in popular culture

- Baba Yaga

- Persephone

- Orpheus and Eurydice

External links

Media related to Izanami at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Izanami at Wikimedia Commons- Izanami on the Japanese History Database.

References

- "Encyclopedia of Shinto - Home : Kami in Classic Texts : Omodaru, Ayakashikone". eos.kokugakuin.ac.jp. Retrieved 2021-01-17.

- Kadoya, Atsushi. "Izanagi". Encyclopedia of Shinto. Kokugakuin University. Retrieved 2020-05-17.

- Phillipi, Donald L. (1969). Kojiki. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press. p. 482.

- Chamberlain (1882). Section II.—The Seven Divine Generations.

- Philippi, Donald L. (1968). Kojiki. p. 480.

- Chamberlain, Basil Hall (1919). The Kojiki. p. 19.

- Matsumura, Takeo (1955). 日本神話の研究, 第2巻 (Nihon shinwa no kenkyu, vol. 2). Baifūkan. p. 56.

- Vovin, Alexander. Immigrants or Overlords? Korean Influences on Japan in the Archaic Period: a Linguistic Perspective. Institut für Kultur und Geitestesgeschichte Asiens, June 14 2012.

- Takeshi, Matsumae (2005). "Izanagi and Izanami". Encyclopedia of Religion. 7: 4754 – via Gale Virtual Reference Library.

- "Izanagi and Izanami". Britannica Encyclopedia of World Religions: 578. 2006 – via ProQuest Ebook Central.

- "Izanagi and Izanami". JapanKnowledge Lib. NetAdvance Inc.

- Kobayashi, Fumihiko (2015). "Japanese Animal-Wife Tales: Narrating Gender Reality in Japanese Folktale Tradition". International Folkloristics. 9 – via ProQuest Ebook Central.

- "Izanagi and Izanami". Britannica Encyclopedia of World Religions: 439. 2006 – via ProQuest Ebook Central.

- Takeshi, Matsumae (2005). Jones, Lindsay (ed.). "Izanagi and Izanami". Encyclopedia of Religion. Detroit, MI: Macmillan Reference, USA. 7: 4754–4755.

- Reader, Ian (2008). Simple Guides: Shinto. Kuperard. pp. 53–55. ISBN 978-1-85733-433-3.