Japanese people

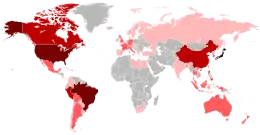

The Japanese people (Japanese: 日本人, Hepburn: Nihonjin) are an East Asian ethnic group native to the Japanese archipelago.[28][29][30][31] Japanese people constitute 97.9% of the population of the country of Japan.[1] Worldwide, approximately 129 million people are of Japanese descent; of these, approximately 122.5 million are residents of Japan.[1] People of Japanese ancestry who live outside Japan are referred to as Nikkeijin (日系人), the Japanese diaspora. Depending on the context, the term ethnic Japanese (日本民族, Nihon minzoku) may be limited or not to mainland Japanese people, specifically the Yamato (as opposed to Ryukyuan and Ainu people).[30][32] Japanese people are one of the largest ethnic groups in the world. In recent decades, there has also been an increase in the number of multiracial people with both Japanese and non-Japanese roots, including half Japanese people.

| Total population | |

|---|---|

c. 129 million

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Significant Japanese diaspora in:[2] | |

| 2,000,000[3] | |

| 1,469,637[4] | |

| 140,134[5]note | |

| 120,000[6][7] | |

| 109,740[8] | |

| 103,949[9] | |

| 89,133[10] (2015) | |

| 76,000[11] | |

| 70,337[12] (2016) | |

| (63,659 note)[13] (2021) | |

| 65,000[14][15] | |

| (41,757 note)[16] (2020) | |

| (40,538 note)[17] (2019) | |

| 36,963[18] (2015) | |

| 36,708[10]note (2014) | |

| 27,429[5] (2015) | |

| 22,000[19] (2014) | |

| 20,373[10] | |

| 20,000[20] | |

| 17,991[10]note (2015) | |

| 16,296[10] (2013) | |

| 14,000[21] | |

| 13,547[22] (2014) | |

| 13,299[10]note (2015) | |

| 10,166[10]note (2014) | |

| 8,655[23] (2015) | |

| 8,080[10]note (2015) | |

| 8,000[24] | |

| 6,616[10] (2015) | |

| 7,000[25] | |

| 6,232[10] (2015) | |

| 6,000[26] note | |

| Languages | |

| Japanese | |

| Religion | |

| Mostly irreligious Traditionally Shinto, Mahayana Buddhism and Shinto sects, with minorities ascribing to Japanese new religions, Christianity, Islam, and other religions[27] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Ainu people · Ryukyuan people | |

^ Note: For this country, only permanent residents with Japanese nationality are included, since the number of naturalized Japanese people and their descendants is unknown. | |

History

Theories of origins

Archaeological evidence indicates that Stone Age people lived in the Japanese archipelago during the Paleolithic period between 39,000 and 21,000 years ago.[33][34] Japan was then connected to mainland Asia by at least one land bridge, and nomadic hunter-gatherers crossed to Japan. Flint tools and bony implements of this era have been excavated in Japan.[35][36]

In the 18th century, Arai Hakuseki suggested that the ancient stone tools in Japan were left behind by the Shukushin. Later, Philipp Franz von Siebold argued that the Ainu people were indigenous to northern Japan.[37] Iha Fuyū suggested that Japanese and Ryukyuan people have the same ethnic origin, based on his 1906 research on the Ryukyuan languages.[38] In the Taishō period, Torii Ryūzō claimed that Yamato people used Yayoi pottery and Ainu used Jōmon pottery.[37]

After World War II, Kotondo Hasebe and Hisashi Suzuki claimed that the origin of Japanese people was not newcomers in the Yayoi period (300 BCE – 300 CE) but the people in the Jōmon period.[39] However, Kazuro Hanihara announced a new racial admixture theory in 1984[39] and a "dual structure model" in 1991.[40] According to Hanihara, modern Japanese lineages began with Jōmon people, who moved into the Japanese archipelago during Paleolithic times, followed by a second wave of immigration, from East Asia to Japan during the Yayoi period (300 BC). Following a population expansion in Neolithic times, these newcomers then found their way to the Japanese archipelago sometime during the Yayoi period. As a result, replacement of the hunter gatherers was common in the island regions of Kyūshū, Shikoku, and southern Honshū, but did not prevail in the outlying islands of Okinawa and Hokkaidō, and the Ryukyuan and Ainu people show mixed characteristics. Mark J. Hudson claims that the main ethnic image of Japanese people was biologically and linguistically formed from 400 BCE to 1,200 CE.[39] Currently, the most well-regarded theory is that present-day Japanese people formed from both the Yayoi rice-agriculturalists and the various Jōmon period ethnicities.[41] However, some recent studies have argued that the Jōmon people had more ethnic diversity than originally suggested[42] or that the people of Japan bear significant genetic signatures from three ancient populations rather than just two.[43][44]

Jōmon and Yayoi periods

Some of the world's oldest known pottery pieces were developed by the Jōmon people in the Upper Paleolithic period, dating back as far as 16,000 years. The name "Jōmon" (縄文 Jōmon) means "cord-impressed pattern", and comes from the characteristic markings found on the pottery. The Jōmon people were mostly hunter-gatherers, but also practicized early agriculture, such as Azuki bean cultivation. At least one middle to late Jōmon site (Minami Mizote (南溝手), ca. 1200–1000 BC) had also a primitive rice-growing agriculture. They relied primarily on fish and nuts for protein. The ethnic roots of the Jōmon period population were heterogeneous and can be traced back to ancient Northeast Asia, the Tibetan plateau, ancient Taiwan, and Siberia.[41][45][46]

Beginning around 300 BC, the Yayoi people from the Korean Peninsula entered the Japanese islands and displaced or intermingled with the Jōmon. The Yayoi brought wet-rice farming and advanced bronze and iron technology to Japan. The more productive paddy field systems allowed the communities to support larger populations and spread over time, in turn becoming the basis for more advanced institutions and heralding the new civilization of the succeeding Kofun period.

The estimated population of Japan in the late Jōmon period was about eight hundred thousand, compared to about three million by the Nara period. Taking the growth rates of hunting and agricultural societies into account, it is calculated that about one and half million immigrants moved to Japan in the period. According to Ann Kumar, the Yayoi created the "Japanese-hierarchical society".[47]

Consolidation and feudal periods

Colonial period

During the Japanese colonial period of 1895 to 1945, the phrase "Japanese people" was used to refer not only to residents of the Japanese archipelago, but also to people from colonies who held Japanese citizenship, such as Taiwanese people and Korean people. The official term used to refer to ethnic Japanese during this period was "inland people" (内地人, naichijin). Such linguistic distinctions facilitated forced assimilation of colonized ethnic identities into a single Imperial Japanese identity.[48]

After the end of World War II, many Nivkh people and Orok people from southern Sakhalin, who held Japanese citizenship in the Karafuto Prefecture, were forced to repatriate to Hokkaidō by the Soviet Union as a part of the Japanese people. On the other hand, many Sakhalin Koreans who had held Japanese citizenship until the end of the war were left stateless by the Soviet occupation.[49]

Language

The Japanese language is a Japonic language that is related to the Ryukyuan languages and was treated as a language isolate in the past. The earliest attested form of the language, Old Japanese, dates to the 8th century. Japanese phonology is characterized by a relatively small number of vowel phonemes, frequent gemination and a distinctive pitch accent system. The modern Japanese language has a tripartite writing system using hiragana, katakana and kanji. The language includes native Japanese words and a large number of words derived from the Chinese language. In Japan the adult literacy rate in the Japanese language exceeds 99%.[50] Dozens of Japanese dialects are spoken in regions of Japan. For now, Japanese is classified as a member of the Japonic languages or as a language isolate with no known living relatives if Ryukyuan is counted as dialects.[51]

Religion

Japanese religion has traditionally been syncretic in nature, combining elements of Buddhism and Shinto (Shinbutsu-shūgō).[52] Shinto, a polytheistic religion with no book of religious canon, is Japan's native religion. Shinto was one of the traditional grounds for the right to the throne of the Japanese imperial family and was codified as the state religion in 1868 (State Shinto), but was abolished by the American occupation in 1945. Mahayana Buddhism came to Japan in the sixth century and evolved into many different sects. Today, the largest form of Buddhism among Japanese people is the Jōdo Shinshū sect founded by Shinran.[53]

A large majority of Japanese people profess to believe in both Shinto and Buddhism.[54][55][56] Japanese people's religion functions mostly as a foundation for mythology, traditions and neighborhood activities, rather than as the single source of moral guidelines for one's life.

According to the annual statistical research on religion in 2018 by the Agency for Culture Affairs, Government of Japan, about two million or slightly 1.5% of Japan's population are Christians.[57] A larger proportion of members of the Japanese diaspora practice Christianity; about 60% of Japanese Brazilians and 90% of Japanese Mexicans are Roman Catholics,[58][59] while about 37% of Japanese Americans are Christians (33% Protestant and 4% Catholic).[60]

Literature

Certain genres of writing originated in and are often associated with Japanese society. These include the haiku, tanka, and I Novel, although modern writers generally avoid these writing styles. Historically, many works have sought to capture or codify traditional Japanese cultural values and aesthetics. Some of the most famous of these include Murasaki Shikibu's The Tale of Genji (1021), about Heian court culture; Miyamoto Musashi's The Book of Five Rings (1645), concerning military strategy; Matsuo Bashō's Oku no Hosomichi (1691), a travelogue; and Jun'ichirō Tanizaki's essay "In Praise of Shadows" (1933), which contrasts Eastern and Western cultures.

Following the opening of Japan to the West in 1854, some works of this style were written in English by natives of Japan; they include Bushido: The Soul of Japan by Nitobe Inazō (1900), concerning samurai ethics, and The Book of Tea by Okakura Kakuzō (1906), which deals with the philosophical implications of the Japanese tea ceremony. Western observers have often attempted to evaluate Japanese society as well, to varying degrees of success; one of the most well-known and controversial works resulting from this is Ruth Benedict's The Chrysanthemum and the Sword (1946).

Twentieth-century Japanese writers recorded changes in Japanese society through their works. Some of the most notable authors included Natsume Sōseki, Jun'ichirō Tanizaki, Osamu Dazai, Fumiko Enchi, Akiko Yosano, Yukio Mishima, and Ryōtarō Shiba. Popular contemporary authors such as Ryū Murakami, Haruki Murakami, and Banana Yoshimoto have been translated into many languages and enjoy international followings, and Yasunari Kawabata and Kenzaburō Ōe were awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Arts

%252C_also_known_as_Red_Fuji%252C_from_the_series_Thirty-six_Views_of_Mount_Fuji_(Fugaku_sanj%C5%ABrokkei)_MET_DP141062.jpg.webp)

Decorative arts in Japan date back to prehistoric times. Jōmon pottery includes examples with elaborate ornamentation. In the Yayoi period, artisans produced mirrors, spears, and ceremonial bells known as dōtaku. Later burial mounds, or kofun, preserve characteristic clay figures known as haniwa, as well as wall paintings.

Beginning in the Nara period, painting, calligraphy, and sculpture flourished under strong Confucian and Buddhist influences from China. Among the architectural achievements of this period are the Hōryū-ji and the Yakushi-ji, two Buddhist temples in Nara Prefecture. After the cessation of official relations with the Tang dynasty in the ninth century, Japanese art and architecture gradually became less influenced by China. Extravagant art and clothing were commissioned by nobles to decorate their court, and although the aristocracy was quite limited in size and power, many of these pieces are still extant. After the Tōdai-ji was attacked and burned during the Genpei War, a special office of restoration was founded, and the Tōdai-ji became an important artistic center. The leading masters of the time were Unkei and Kaikei.

Painting advanced in the Muromachi period in the form of ink wash painting under the influence of Zen Buddhism as practiced by such masters as Sesshū Tōyō. Zen Buddhist tenets were also elaborated into the tea ceremony during the Sengoku period. During the Edo period, the polychrome painting screens of the Kanō school were made influential thanks to their powerful patrons (including the Tokugawas). Popular artists created ukiyo-e, woodblock prints for sale to commoners in the flourishing cities. Pottery such as Imari ware was highly valued as far away as Europe.

In theater, Noh is a traditional, spare dramatic form that developed in tandem with kyōgen farce. In stark contrast to the restrained refinement of noh, kabuki, an "explosion of color", use every possible stage trick for dramatic effect. Plays include sensational events such as suicides, and many such works were performed in both kabuki and bunraku puppet theaters.

Since the Meiji Restoration, Japan has absorbed elements of Western culture and has given them a "Japanese" feel or modification into it. It's modern decorative, practical, and performing arts works span a spectrum ranging from the traditions of Japan to purely Western modes. Products of popular culture, including J-pop, J-rock, manga and anime have found audiences and fans around the world.

Citizenship

Article 10 of the Constitution of Japan defines the term "Japanese" based upon Japanese nationality.[61] The concept of "ethnic groups" in Japanese census statistics differs from the concept applied in many other countries. For example, the United Kingdom Census queries the respondent's "ethnic or racial background", regardless of nationality.[62] The Japanese Statistics Bureau, however, asks only about nationality in the census. The Government of Japan regards all naturalized Japanese citizens and native-born Japanese nationals with a multi-ethnic background as Japanese. There is no distinction based on ethnicity. There's no official ethnicity census data.[63] Because the census equates nationality with ethnicity, its figures erroneously assume that naturalized Japanese citizens and Japanese nationals with multi-ethnic backgrounds are ethnically Japanese. John Lie, Eiji Oguma, and other scholars problematize the widespread belief that Japan is ethnically homogeneous, arguing that it is more accurate to describe Japan as a multiethnic society,[64][65] although such claims have long been rejected by conservative elements of Japanese society such as former Japanese Prime Minister Tarō Asō, who once described Japan as being a nation of "one race, one civilization, one language and one culture".[66] There is an increase of hāfu (half Japanese) people, but the amount is relatively small. Studies from e.g. 2015 estimate that 1 in 30 children born in Japan are born to interracial couples.[67]

Diaspora

The term nikkeijin (日系人) is used to refer to Japanese people who emigrated from Japan and their descendants.

Emigration from Japan was recorded as early as the 15th century to the Philippines and Borneo,[68][69][70][71] and in the 16th and 17th centuries, thousands of traders from Japan also migrated to the Philippines and assimilated into the local population.[72]: pp. 52–3 However, migration of Japanese people did not become a mass phenomenon until the Meiji era, when Japanese people began to go to Canada, the United States, the Philippines, China, Brazil, and Peru. There was also significant emigration to the territories of the Empire of Japan during the colonial period, but most of these emigrants and settlers repatriated to Japan after the end of World War II in Asia.[73]

According to the Association of Nikkei and Japanese Abroad, there are about 2.5 million nikkeijin living in their adopted countries. The largest of these foreign communities are in the Brazilian states of São Paulo and Paraná.[74] There are also significant cohesive Japanese communities in the Philippines,[75] East Malaysia, Peru, Argentine provinces of Buenos Aires, Córdoba and Misiones, the U.S. states of Hawaii, California, and Washington, and the Canadian cities of Vancouver and Toronto. Separately, the number of Japanese citizens living abroad is over one million according to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

See also

- Ethnic groups of Japan

- Ethnic issues in Japan

- Foreign-born Japanese

- Japantown

- List of Japanese people

- Nihonjinron

- Demographics of Japan

- Burakumin

- Dekasegi

- Hāfu, half Japanese people

- Azumi people, an ancient group of peoples who inhabited parts of northern Kyushu

- Emishi, a group of people who lived in the northeastern Tōhoku region of Japan

- Kuzu, an ancient people of Japan believed to have lived along the Yoshino River

References

- "Population Estimates by Age (Five-Year Groups) and Sex". stat.go.jp. Statistics Bureau of Japan. Retrieved August 6, 2022.

- MOFA 国・地域. Mofa.go.jp. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- "Japan-Brazil Relations (Basic Data)". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. Retrieved July 14, 2016.

- Bureau, U.S. Census. "American FactFinder - Results". Factfinder2.census.gov. Archived from the original on October 12, 2016. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- 海外在留邦人数調査統計 [Annual Report of Statistics on Japanese Nationals Overseas] (PDF). Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan (in Japanese). October 1, 2010.

- Agnote, Dario (October 11, 2006). "A glimmer of hope for castoffs". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011. Retrieved August 9, 2016.

- Ohno, Shun (2006). "The Intermarried issei and mestizo nisei in the Philippines". In Adachi, Nobuko (ed.). Japanese diasporas: Unsung pasts, conflicting presents, and uncertain futures. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-135-98723-7.

- Canada, Government of Canada, Statistics (May 8, 2013). "2011 National Household Survey: Data tables – Ethnic Origin (264), Single and Multiple Ethnic Origin Responses (3), Generation Status (4), Age Groups (10) and Sex (3) for the Population in Private Households of Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2011 National Household Survey". 12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- "Japan-Peru Relations (Basic Data)". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- "Annual Report of Statistics on Japanese Nationals Overseas" (PDF). Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- "Japan-Mexico Relations". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan.

- MOFA 2016 タイ王国. Mofa.go.jp. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- "Japan-United Kingdom Relations (Basic Data)". Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Japan). July 5, 2022. Archived from the original on August 26, 2022. Retrieved October 22, 2022.

- "Japan-Argentine Relations". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan.

- "Argentina inicia una nueva etapa en su relación con Japón". Telam.com.ar. Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- ドイツ連邦共和国(Federal Republic of Germany) 基礎データ [Germany basic data]. Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Japan) (in Japanese). December 10, 2021. 二国間関係 4 在留邦人数. Archived from the original on October 10, 2022. Retrieved October 22, 2022.

- "Japan-France Relations (Basic Data)". Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Japan). March 17, 2021. Archived from the original on August 26, 2022. Retrieved October 22, 2022.

- "Japan-Singapore Relations". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- "Japan-Malaysia Relations (Basic Data)". Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan. September 7, 2015. Archived from the original on June 25, 2016. Retrieved June 26, 2016.

- "Letter from Ambassador of FSM to Japan, Micronesia Registration Advisors, Inc" (PDF). Embassy of the Federated States of Micronesia. February 24, 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 12, 2020. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- 多汗症【薬局にある市販の薬】病院に行かず汗止め薬で改善. Fenaboja.com. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- ベトナム社会主義共和国(Socialist Republic of Viet Nam). Mofa.go.jp. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- インド(India). Mofa.go.jp. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- "The New Caledonia Weekly" (PDF). October 14, 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 14, 2008. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- "Japan-Paraguay Relations". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. March 24, 2015. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- "Pacific Islands President, Bainbridge Lawmakers Find Common Ground » Kitsap Sun". July 16, 2011. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- "International Religious Freedom Report 2006". Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. U.S. Department of State. September 15, 2006. Retrieved December 4, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - "Japan - People". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- "Japan. B. Ethnic Groups". Encarta. Archived from the original on January 22, 2008.

- "人類学上は,旧石器時代あるいは縄文時代以来,現在の北海道〜沖縄諸島(南西諸島)に住んだ集団を祖先にもつ人々。" ( 日本人. マイペディア. 平凡社.)

- "日本民族という意味で、文化を基準に人間を分類したときのグループである。また、文化のなかで言語はとくに重要なので、日本民族は日本語を母語としてもちいる人々とほぼ考えてよい。" ( 日本人. エンカルタ. Microsoft.)

- Minahan, James B. (2014), Ethnic Groups of North, East, and Central Asia: An Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, pp. 231–233, ISBN 978-1-61069-018-8

- Global archaeological evidence for proboscidean overkill Archived June 26, 2008, at the Wayback Machine in PNAS online; Page 3 (page No.6233), Table 1. The known global sample of proboscidean kill/scavenge sites :Lake Nojiri Japan 33-39 ka (ka: thousand years).

- "Prehistoric Times". Web Site Shinshu. Nagano Prefecture. Archived from the original on December 31, 2010. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

- 野尻湖人の世界. May 19, 2000. Archived from the original on May 19, 2000. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- "野尻湖発掘調査団ホームページ". July 27, 2004. Archived from the original on July 27, 2004.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Imamura, Keiji (2000). "Archaeological Research of the Jomon Period in the 21st Century". The University Museum, The University of Tokyo. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved December 29, 2010.

- 伊波普猷の卒論発見 思想骨格 鮮明に (in Japanese). Ryūkyū Shimpō. July 25, 2010. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved March 7, 2011.

- Nanta, Arnaud (2008). "Physical Anthropology and the Reconstruction of Japanese Identity in Postcolonial Japan". Social Science Japan Journal. 11 (1): 29–47. doi:10.1093/ssjj/jyn019.

- Hanihara, K (1991). "Dual structure model for the population history of the Japanese". Japan Review. 2: 1–33.

- Boer, Elisabeth de; Yang, Melinda A.; Kawagoe, Aileen; Barnes, Gina L. (2020). "Japan considered from the hypothesis of farmer/language spread". Evolutionary Human Sciences. 2. doi:10.1017/ehs.2020.7. ISSN 2513-843X.

- Lee, Hasegawa, Sean, Toshikazu (April 2013). "Evolution of the Ainu Language in Space and Time". PLOS ONE. 8 (4): e62243. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...862243L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062243. PMC 3637396. PMID 23638014. S2CID 8370300.

- Dunham, W. (September 18, 2021). "Study rewrites understanding of modern Japan's genetic ancestry". Reuters.

- Cooke, N. P.; Mattiangeli, V.; Cassidy, L. M.; Okazaki, K.; Stokes, C. A.; Onbe, S.; Hatakeyama, S.; Machida, K.; Kasai, K.; Tomioka, N.; Matsumoto, A.; Ito, M.; Kojima, Y.; Bradley, D. G.; Gakuhari, T.; Nakagome, S. (September 17, 2021). "Ancient genomics reveals tripartite origins of Japanese populations". Science Advances. 7 (38): eabh2419. Bibcode:2021SciA....7H2419C. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abh2419. PMC 8448447. PMID 34533991.

- Watanabe, Yusuke; Ohashi, Jun (March 8, 2021). "Comprehensive analysis of Japanese archipelago population history by detecting ancestry-marker polymorphisms without using ancient DNA data". bioRxiv: 2020.12.07.414037. doi:10.1101/2020.12.07.414037. S2CID 229293389.

- Yang, Melinda A.; Fan, Xuechun; Sun, Bo; Chen, Chungyu; Lang, Jianfeng; Ko, Ying-Chin; Tsang, Cheng-hwa; Chiu, Hunglin; Wang, Tianyi; Bao, Qingchuan; Wu, Xiaohong (July 17, 2020). "Ancient DNA indicates human population shifts and admixture in northern and southern China". Science. 369 (6501): 282–288. Bibcode:2020Sci...369..282Y. doi:10.1126/science.aba0909. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 32409524. S2CID 218649510.

- Kumar, Ann (2009). Globalizing the Prehistory of Japan: Language, Genes, and Civilization. Oxford: Routledge.

- Eika Tai (September 2004). "Korean Japanese". Critical Asian Studies. 36 (3): 355–382. doi:10.1080/1467271042000241586. S2CID 147377282.

- Lankov, Andrei (January 5, 2006). "Stateless in Sakhalin". The Korea Times. Archived from the original on February 21, 2006. Retrieved November 26, 2006.

- "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- Kindaichi, Haruhiko (2011-12-20). Japanese Language: Learn the Fascinating History and Evolution of the Language Along With Many Useful Japanese Grammar Points. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 9781462902668

- Satō Makoto. "Shinto and Buddhism". Kokugakuin University Encyclopedia of Shinto. Archived from the original on April 1, 2018. Retrieved March 31, 2018.

- 宗教統計調査 / 平成29年度 (Japanese government statistics on total religious followers for 2017). e-stat.go.jp. Retrieved March 31, 2018.

- "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". Cia.gov. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- "Japan". State.gov. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- "Buddhists in the world". July 4, 2004. Archived from the original on July 4, 2004. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- 宗教年鑑 令和元年版 [Religious Yearbook 2019] (PDF) (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs, Government of Japan. 2019. p. 35.

- "PANIB - Pastoral Nipo Brasileira". October 15, 2007. Archived from the original on October 15, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "Colonia japonesa en México visita Guadalupe en 54º peregrinación anual". Aciprensa. Retrieved February 20, 2014.

- "Asian Americans: A Mosaic of Faiths". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. July 19, 2012. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- [日本国憲法]

- "United Kingdom population by ethnic group". United Kingdom Census 2001. Office for National Statistics. April 1, 2001. Archived from the original on January 7, 2010. Retrieved September 10, 2009.

- 平成20年末現在における外国人登録者統計について(Number of Foreign residents in Japan). Moj.go.jp. Retrieved November 9, 2011.

- John Lie Multiethnic Japan (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2001)

- Oguma Eiji, A Genealogy of 'Japanese' Self-images (Melbourne: Trans Pacific Press, 2002)

- "Aso says Japan is nation of 'one race'". The Japan Times. October 18, 2005.

- "Being 'hafu' in Japan: Mixed-race people face ridicule, rejection". America.aljazeera.com. Retrieved January 24, 2019.

- "Ancient Japanese pottery in Boljoon town". May 30, 2011.

- Manansala, Paul Kekai (September 5, 2006). "Quests of the Dragon and Bird Clan: Luzon Jars (Glossary)".

- Cole, Fay-Cooper (1912). "Chinese Pottery in the Philippines" (PDF). Field Museum of Natural History. Anthropological Series. 12 (1).

- "Hotels in Philippines - Booked.net". Booked.net. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- Leupp, Gary P. (January 1, 2003). Interracial Intimacy in Japan. ISBN 9780826460745.

- Lankov, Andrei (March 23, 2006). "The Dawn of Modern Korea (360): Settling Down". The Korea Times. Archived from the original on June 19, 2006. Retrieved December 18, 2006.

- IBGE. Resistência e Integração: 100 anos de Imigração Japonesa no Brasil apud Made in Japan. IBGE Traça o Perfil dos Imigrantes; 21 de junho de 2008 Archived June 24, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Accessed September 4, 2008. (in Portuguese)

- Furia, Reiko (1993). "The Japanese Community Abroad: The Case of Prewar Davao in the Philippines". In Saya Shiraishi; Takashi Shiraishi (eds.). The Japanese in Colonial Southeast Asia. Southeast Asia Program, Cornell University Publications. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-87727-402-5. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

External links

- CIA The World Fact Book 2006

- The Association of Nikkei & Japanese Abroad

- Discover Nikkei- Information on Japanese emigrants and their descendants

- Jun-Nissei Literature and Culture in Brazil

- The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan

- The National Museum of Japanese History

- Japanese society and culture

- Dekasegi and their issues living in Japan (Japanese/Portuguese)

.svg.png.webp)