John Eliot Gardiner

Sir John Eliot Gardiner CBE HonFBA (born 20 April 1943)[1] is an English conductor, particularly known for his performances of the works of Johann Sebastian Bach.

Sir John Eliot Gardiner CBE HonFBA | |

|---|---|

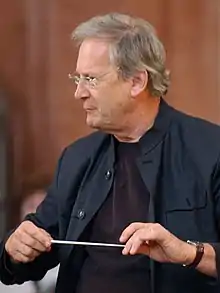

Gardiner in rehearsal, 2007 | |

| Born | 20 April 1943 Fontmell Magna, Dorset, UK |

| Occupation | Conductor of classical music |

| Years active | 1964–present |

Life and career

Born in Fontmell Magna, Dorset, son of Rolf Gardiner and Marabel Hodgkin, Gardiner's early musical experience came largely through singing with his family and in a local church choir. As a child he grew up with the celebrated Haussmann portrait of J. S. Bach, which had been lent to his parents for safe keeping during the Second World War.[2] A self-taught musician who also played the violin, he began to study conducting at the age of 15. He was educated at Bryanston School, then studied history at King's College, Cambridge, where his tutor was the social anthropologist Edmund Leach.[3][4]

While an undergraduate at Cambridge he launched his career as a conductor with a performance of Vespro della Beata Vergine by Monteverdi, in King's College Chapel on 5 March 1964.[5] This either featured or led to the foundation of the Monteverdi Choir, with which he made his London conducting debut at the Wigmore Hall in 1966.[3] Whilst at Cambridge, he conducted the Oxford and Cambridge Singers on a concert tour of the Middle East.[3] After graduating in history, Gardiner continued his musical studies at King's College London under Thurston Dart and in Paris with Nadia Boulanger, whose music had been a very early influence.[6]

Returning to England, Gardiner joined the BBC Northern Orchestra as an apprentice conductor.[6] In 1968 he founded the Monteverdi Orchestra. Upon changing from modern instruments to period instruments in 1977, the orchestra changed its name to the English Baroque Soloists in 1978.[7][8] In 1969 Gardiner made his opera debut with a performance of Mozart's The Magic Flute at the English National Opera. Four years later, in 1973, he made his first appearance at the Covent Garden conducting Gluck's Iphigénie en Tauride. The English Baroque Soloists made their opera debut with him in the 1977 Innsbruck Festival of Early Music, performing Handel's Acis and Galatea on period instruments. His American debut came in 1979 when he conducted the Dallas Symphony Orchestra. He then became the lead conductor of Canada's CBC Vancouver Orchestra from 1980 to 1983.[9]

After his period with the CBC Vancouver Orchestra, Gardiner went to France. From 1983 to 1988 he was Music Director of the Opéra National de Lyon. During his period with the Opéra he founded an entirely new orchestra.[10] During his time with the Opéra National de Lyon Gardiner was also Artistic Director of the Göttingen Handel Festival (1981 until 1990).[11] In 1989 the Monteverdi Choir had its 25th anniversary, touring the world giving performances of Handel's oratorio Israel in Egypt and Bach's Magnificat among other works. In 1990, Gardiner formed a new period-instrument orchestra, the Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique, to perform music of the 19th century. From 1991 until 1995 he was principal conductor of the North German Radio Symphony Orchestra.

From the 1990s onwards he undertook more world tours with his ensembles, including:

- A European tour in 1993 with the Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique featured Berlioz's rediscovered Messe solennelle. Beginning in Bremen, Germany the tour ended with a recorded performance in Westminster Cathedral, London 1993.

- In 2000, Gardiner set out on his Bach Cantata Pilgrimage, performing, over a 52-week period, all of Bach's sacred cantatas in churches around Europe and the United States.[12]

- In late 2004, Gardiner toured France and Spain with the Monteverdi Choir performing pieces from the Codex Calixtinus in cathedrals and churches along the Camino de Santiago.[13]

He founded the Monteverdi Choir (1964), the English Baroque Soloists (1978) and the Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique (1989). Gardiner has recorded over 250 albums with these and other musical ensembles, most of which have been published by Deutsche Grammophon and Philips Classics,[14] and by the Soli Deo Gloria label, which specialises in recordings by Gardiner and by his ensembles.

Gardiner is most famous for his interpretations of Baroque music on period instruments with the Monteverdi Choir and the English Baroque Soloists, but his repertoire and discography are not limited to early music. With the Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique Gardiner has performed a wide range of Classical and Romantic music, including many works of Berlioz and all of Beethoven's symphonies. A recording of the third symphony of the latter was used in a dramatisation by the BBC of Beethoven's writing of that symphony.[15] Gardiner has served as chief conductor of the North German Radio Symphony Orchestra and has appeared as guest conductor with such major orchestras as the Berlin Philharmonic, Boston Symphony Orchestra, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Cleveland Orchestra, London Symphony Orchestra, Philharmonia, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra and Vienna Philharmonic. Gardiner is also well known for his refusal to perform the music of Richard Wagner; in a 2008 interview for Gramophone Gardiner said, 'I really loathe Wagner – everything he stands for – and I don’t even like his music very much.'[16]

In late 2012, citing health concerns, he cancelled his planned December 2013 tour of Australia with the Monteverdi Choir and the Australian Chamber Orchestra.[17] In 2013, Gardiner published the book Bach: Music in the Castle of Heaven.[18] In 2014 he started a five-year term as President of the Leipzig Bach Archive, being succeeded by Ton Koopman in that position in 2019.[19][20] One of the realizations during Gardiner's presidency was the Archive's collaboration to the Bach 333 box set with the complete recordings of Johann Sebastian Bach's works, released in 2018.[21]

Honours and awards

Gardiner has received a variety of honours and awards,[22] including:

- Honorary doctorate from the University of Lyon, 1987[14]

- Commander of the Order of the British Empire, 1990 New Year Honours[23]

- Honorary Fellow of King's College, London and King's College, Cambridge

- Honorary Member of Royal Academy of Music, 1992[14]

- Grammy, Best Choral Performance, 1994[24]

- Knight Bachelor, 1998[25]

- Grammy, Best Opera Recording, 1999[24]

- Bach Medal, 2005[26]

- Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany, 2005[27]

- Doctorate Honoris Causa in Musicology at the University of Pavia in Cremona (birthplace of Claudio Monteverdi), 2006[14][28]

- Bach Prize of the Royal Academy of Music-Kohn Foundation, 2008[14]

- Voted into the Gramophone Hall of Fame in 2012[29]

- Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur, 2011.

- Honorary Degree of Doctor of Music from the University of St Andrews, 2014[30]

- National Book Critics Circle Award (Biography) shortlist for Bach: Music in the Castle of Heaven, 2014[31]

- Honorary Degree of Doctor of Music from the University of Cambridge, 2015

- Honorary Fellow of the British Academy, 2015[32]

Personal life

Gardiner is the son of the British rural revivalist Rolf Gardiner (1902–1971), and the grandson of the Egyptologist Alan Gardiner (1879–1963). His mother, Marabel Hodgkin, was a member of the Hodgkin family, a notable Quaker family; the artist Sir Howard Hodgkin (1932–2017) was Gardiner's first cousin.[33]

Gardiner was married to violinist Elizabeth Wilcock from 1981 to 1997; they have three daughters. From 2001 to 2019 he was married to Isabella de Sabata,[34] granddaughter of conductor Victor de Sabata.[35]

In his spare time, Gardiner runs an organic farm at Springhead near Fontmell Magna[36] in North Dorset, which was established by his great uncle, composer Henry Balfour Gardiner. His continued involvement in this project has earned him the nickname 'Uphill Gardiner' as a consequence of his unorthodox farming methods.

In August 2014, Gardiner was one of 200 public figures who were signatories to a letter to The Guardian opposing Scottish independence in the run-up to September's referendum on that subject.[37]

Gardiner has been the subject of various allegations of rudeness and bullying of performers and colleagues.[38][39][40]

Selected publications

- Music in the Castle of Heaven: A Portrait of Johann Sebastian Bach. Penguin UK. 2013. ISBN 978-1-84614-721-0.

See also

- Soli Deo Gloria, Gardiner's label, the name of which is taken from Bach's signature.

References

- "Birthdays today". The Telegraph. 20 April 2012. Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

Sir John Eliot Gardiner, conductor, 69

- Service, Tom; Tilden, Imogen (29 April 2015). "Bach Portrait Returns to Leipzig". The Guardian.

- "John Eliot Gardiner", in Contemporary Musicians (1999), Detroit: Gale

- Gardiner, John Eliot (2015). Bach : Music in the Castle of Heaven (US ed.). New York: Knopf. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-375-41529-6.

- Whenham, John (1997). Monteverdi, Vespers (1610). Cambridge University Press. p. 85. ISBN 0-521-45377-1.

- Gardiner, John Eliot (2015). Bach : Music in the Castle of Heaven (US ed.). New York: Knopf. pp. 6–8. ISBN 978-0-375-41529-6.

- "The Monteverdi Choir at 50". Monteverdi Choir. Archived from the original (Flash) on 26 November 2015. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- "English Baroque Soloists". Sinfini Music. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- CBC Radio Orchestra, archived from the original on 21 August 2007, retrieved 17 May 2007

- The Opera House Orchestra, archived from the original on 3 December 2006, retrieved 17 May 2007

- Göttingen Händelfestspiele (2007), A Brief History of the Göttingen Händelfestspiele (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 15 June 2007, retrieved 17 May 2007

- Bach Cantata Pilgrimage, archived from the original on 26 April 2007, retrieved 17 May 2007

- Santiago Pilgrimage 2004 Website, archived from the original on 15 May 2007, retrieved 17 May 2007

- Monteverdi Productions website, archived from the original on 8 June 2007, retrieved 17 May 2007

- "Ian Hart is Beethoven in unique drama of the first performance of the Eroica Symphony" (Press release). BBC. 15 May 2003. Retrieved 17 May 2007.

- Peter Quantrill (October 2008). "Sir John Eliot Gardiner – Interview". gramophone.co.uk.

- "John Eliot Gardiner pulls out of ACO Christmas concerts". Limelightmagazine.com.au. 19 October 2012. Archived from the original on 29 July 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- Gardiner, John Eliot (2013). Bach a Biography Through the Music. London: Penguin Books, Limited. ISBN 978-0-7139-9662-3. Archived from the original on 6 November 2015. Retrieved 6 December 2015. Reprinted 2015 , Vintage, ISBN 978-1-4000-3143-6

- Smith, Charlotte (2013). "Sir John Eliot Gardiner named president". Gramophone. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- "A New President for The Leipzig Bach Archive | Bach-Archiv Leipzig". www.bach-leipzig.de. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- Bach 333 website (26 October 2018)

- John Eliot Gardiner (Bio), retrieved 17 May 2007

- "No. 51981". The London Gazette (Supplement). 29 December 1989. p. 7.

- Grammy Award Winners, archived from the original on 30 September 2007, retrieved 17 May 2007

- "No. 55610". The London Gazette. 14 September 1999. pp. 9843–9844.

- "Sir John Eliot Gardiner erhält Leipziger Bach-Medaille". neue musikzeitung (Press release) (in German). Regensburg: ConBrio Verlagsgesellschaft mbH. ddp. 22 April 2005. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- Sir John Eliot Gardiner erhält Bundesverdienstkreuz (in German), archived from the original on 4 March 2016, retrieved 5 December 2005

- "2006 – Università degli studi di Pavia". diazilla.com (in Italian). Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- "Sir John Eliot Gardiner (conductor)". Gramophone. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- "Laureation address – Sir John Eliot Gardiner". Retrieved 27 June 2014.

- "Announcing the National Book Critics Awards Finalists for Publishing Year 2013". National Book Critics Circle. 14 January 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- "British Academy Fellowship reaches 1,000 as 42 new UK Fellows are welcomed". 16 July 2015.

- Battle, Laura (30 March 2017). "Conductor John Eliot Gardiner on his love of music and farming". Financial Times.

- "A maestro marriage is over". Slipped Disc. 4 August 2019. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- John Eliot Gardiner – gewend zijn eigen beslissingen te nemen (Dutch), archived from the original on 1 October 2006, retrieved 17 May 2007

- "a rural centre for creative and sustainable living in Fontmell Magna Dorset". Springhead Trust. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- "Celebrities' open letter to Scotland – full text and list of signatories | Politics". theguardian.com. 7 August 2014. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- "Lunch with the FT: John Eliot Gardiner". Financial Times. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- Thompson, Damian (2 May 2015). "The Heckler: why does John Eliot Gardiner have to be so rude?". The Spectator. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- Phillips, Peter (5 April 2014). "The mean, bullying maestro is extinct – or should be". The Spectator. Retrieved 15 March 2019.