Lenin's Mausoleum

Lenin's Mausoleum (from 1953 to 1961 Lenin's & Stalin's Mausoleum) (Russian: Мавзолей Ленина, tr. Mavzoley Lenina, IPA: [məvzɐˈlʲej ˈlʲenʲɪnə]), also known as Lenin's Tomb, situated on Red Square in the centre of Moscow, is a mausoleum that serves as the resting place of Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin. His preserved body has been on public display there since shortly after his death in 1924, with rare exceptions in wartime. Alexey Shchusev's granite structure incorporates some elements from ancient mausoleums, such as the Step Pyramid, the Tomb of Cyrus the Great and, to some degree, the Temple of the Inscriptions.

Мавзолей Ленина Mavzoley Lenina | |

.jpeg.webp) Lenin's Mausoleum, 2006 | |

| |

| Coordinates | 55°45′13″N 37°37′11″E |

|---|---|

| Location | Moscow, Russia |

| Designer | Alexey Shchusev |

| Type | Memorial |

| Material | Concrete and marble |

| Completion date | 10 November 1930 |

| Dedicated to | Vladimir Lenin Joseph Stalin (formerly) |

History

.jpg.webp)

Lenin died on 21 January 1924. Two days later, architect Alexey Shchusev was tasked with building a structure suitable for viewing of the body by mourners. A wooden tomb, in Red Square by the Moscow Kremlin Wall, was ready on January 27, and later that day Lenin's coffin was placed in it. More than 100,000 people visited the tomb in the next six weeks.[1] By the end of May, Shchusev had replaced the tomb with a larger, more elaborate one, and Lenin's body was transferred to a sarcophagus designed by architect Konstantin Melnikov.[2] The new wooden mausoleum was opened to the public on August 1, 1924.[2]

Pathologist Alexei Ivanovich Abrikosov had embalmed Lenin's body shortly after his death and Boris Zbarsky and Vladimir Vorobiev were tasked with the ongoing preservation of the body. After graduating from Moscow University, Ilya Zbarsky became his father's assistant, and likened the work on Lenin's body to that of ancient Egyptian priests. In 1925, Boris Zbarsky and Vorobiev urged the government to replace the wooden structure after mold was found in the walls and even on the body itself.[3] A new mausoleum of marble, porphyry, granite, and labradorite (by Alexey Shchusev, I.A. Frantsuz and G.K. Yakovlev) was completed in 1930. The mausoleum also served as a viewing stand for Soviet leaders to review parades on Red Square.

In 1973, sculptor Nikolai Tomsky designed a new sarcophagus.

On 26 January 1924, the Head of the Moscow Garrison issued an order to place the guard of honour at the mausoleum.[4] Russians call it the "Number One Sentry". After the events of the Russian constitutional crisis of 1993, the guard of honour was disbanded. In 1997, the "Number One Sentry" was restored at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Alexander Garden.

Lenin's body was removed in October 1941 and evacuated to Tyumen, in Siberia, when it appeared that Moscow might be in danger of capture by German troops. After the war, it was returned and the tomb reopened.

More than 10 million people visited Lenin's tomb between 1924 and 1972.

Joseph Stalin's embalmed body shared a spot next to Lenin's, from the time of his death in March 1953 until October 1961, when Stalin was removed as part of de-Stalinization and Khrushchev's Thaw, and buried in the Kremlin Wall Necropolis outside the walls of the Kremlin.

Lenin's body was to have been transferred to the Pantheon upon its completion but the project was cancelled in the aftermath of de-Stalinization.

Architectural features

Project selection and construction

In January 1925, the Presidium of the USSR Central Executive Committee announced an international competition to design a stone tomb for Lenin. The commission received 117 suggestions and sketches. Among them, there were offered different variants: the ship with Lenin's figure on board, the round mausoleum in a shape of a globe, the analogue of Egypt pyramid, the mausoleum in a shape of the five-pointed star. But after considering the proposed designs, the commission decided to retain the image of a wooden mausoleum. Architect Shchusev created some new drawings based on old sketches and made a model in granite, and his project was approved.[5] It was decided to clad the new building with red granite, as well as black and grey Labrador.

The basement under the sarcophagus weighed 20 tons, it was installed on a thick layer of sand, and around the slab were driven guarding piles - it protected the tomb from vibration even during the passage of heavy tanks over the area. Other monoliths weighed from 1 to 10 tons. Altogether 2900 m2 of polished granite was required for the construction, each square metre of which was processed for three days on average. The upper slab of red Karelian quartzite was placed on columns of granite, whose different species were specially brought to Moscow from all the republics of the USSR.[6]

The stone mausoleum was erected in 16 months - by October 1930. Compared to the wooden one, the new building was built three metres higher, the outer volume was increased 4.5 times - 5800 m³, and the inner volume 12 times, up to 2400 m³. Its total weight was about 10,000 tonnes. The mausoleum occupied the highest point on Red Square.[7]

During construction, the mausoleum and the necropolis were brought to a unified architectural design: differently characterised tombstones and monuments were removed, individual and collective burials at Nikolskaya and Spasskaya Towers were united, and the fence was redesigned and installed. Guest stands for ten thousand seats were installed on either side of the mausoleum.

Interiors

The mausoleum contains a vestibule, Mourning Hall and two staircases. Opposite the entrance is a huge granite block was carved the coat of arms of the USSR of 1923.[5]

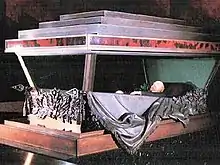

Two stairs are leading down from the vestibule. The left staircase is three meters wide and takes visitors down to the Funeral Hall. The walls of the descent are of grey labradorite with a ledged panel of labradorite and black labradorite. The Funeral Hall is a ten-meter cube with a stepped ceiling. A black labradorite band runs across the entire room, on which pilasters of red porphyry are placed. Next to the pilasters are bands of bright red smalt and to the right of the smalt are bands of black labradorite. This combination creates the effect of flames and banners flying in the wind. In the centre of the hall is a black pedestal with a sarcophagus.[5]

The upper stepped slab of the sarcophagus is supported by four inconspicuous metal columns, which gives the impression that the slab is hanging in the air. The lower slab is covered in reddish jasper. The sarcophagus is made up of two inclined conical glasses, which are held together by a bronze frame. Illuminators and light filters are embedded in the upper part of the frame - they give an animating pink coloring and reduce heating. On either side of the sarcophagus are the battle and labour bronze banners, which appear satiny due to the special illumination. In the headboard is the coat of arms of the USSR framed by oak and laurel branches. At the foot, there are branches twisted with ribbon.

Exit from the Funeral Hall to the right-hand staircase leads to the Red Square.

Preserving the body

One of the main problems the embalmers faced was the appearance of dark spots on the skin, especially on the face and hands. They managed to solve the problem by the use of a variety of different reagents. While working on ways to preserve Lenin's body, Boris Zbarsky invented a new way to purify medical chloroform used for preservation.[8] For example, if a patch of wrinkling or discoloration occurred it was treated with a solution of acetic acid and ethyl alcohol diluted with water. Hydrogen peroxide could be used to restore the tissues' original coloring. Damp spots were removed by means of disinfectants such as quinine or phenol.[9] Lenin's remains are soaked in a solution of glycerol and potassium acetate on a yearly basis.[10] Synthetic eyeballs were placed in Lenin's orbital cavities to prevent his eye sockets from collapsing.[11]

Until the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, the continued preservation work was funded by the Soviet government. At that point the government discontinued financial support and private donations then supported the preservation staff.[12] In 2016 the Russian government reversed its earlier decision and said it planned to spend 13 million rubles to preserve the body.[13]

Contemporary

_01.jpg.webp)

The Mausoleum is open to the public on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, Thursdays, Saturdays, and Sundays from 10:00–13:00.[14] Visitors still queue to see Lenin's body although queues are not as long as they once were. Entrance is free of charge. Before visitors are allowed to enter the mausoleum, armed police or military guards search them. Visitors are required to show respect whilst inside the tomb: photography and filming inside the mausoleum are forbidden, as is talking, smoking, keeping hands in pockets, or wearing hats (unless female).[15]

Since 1991, there has been some discussion about removing Lenin's body to the Kremlin Wall Necropolis and burying it there. President Boris Yeltsin, with the support of the Russian Orthodox Church, intended to close the tomb and bury Lenin next to his mother, Maria Alexandrovna Ulyanova, at the Volkov Cemetery in St. Petersburg. His successor, Vladimir Putin, opposed this, stating that a reburial of Lenin would imply that generations of citizens had observed false values during seventy years of Soviet rule.[16]

The mausoleum has undergone several changes in appearance since the collapse of the Soviet Union. One of the first noticeable changes was the placement of gates at the staircases leading to the central tribune. After the removal of the guard, this was necessary to prevent unauthorised usage of the tribune. Beginning in 2012, the mausoleum underwent foundation reconstruction caused by the construction of a building attached to the mausoleum in 1983. The building houses an escalator once used by members of the Politburo to ascend the tribune. In 1995–96, when Boris Yeltsin used the tribune, he used stairs and not the escalator. Now the tribune is no longer used, therefore it became acceptable to remove the escalator. The building was closed in 2013 for renovations. It was finally opened on April 30, 2013, in time for the May 1 celebration of "The Day of Spring and Labour". In 2018, RIA Novosti reported that Vladimir Petrov, a member of the legislative assembly of the Leningrad Oblast, proposed creating a special commission in order to examine the question of the removal of Lenin's body from the Mausoleum. Petrov seemed to be willing to replace the corpse with a copy made of synthetic resin.[17] The deputy Dmitry Novikov, a member of the Communist Party, has strongly opposed Petrov's proposition.

Honours

- The Hungarian People's Republic issued a postage stamp depicting it on 20 February 1952.

- The Soviet Union issued postage stamps depicting it in 1925, 1934, 1944, 1946, 1947, 1948, and 1949.

See also

- Kumsusan Palace of the Sun

- Ho Chi Minh Mausoleum

- Kremlin Wall Necropolis

- Tampere Lenin Museum

- Chairman Mao Memorial Hall

- Pyramid of Tirana

- House of Flowers

- Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum

- Che Guevara Mausoleum

- Santa Ifigenia Cemetery

- Sükhbaatar's Mausoleum

- Georgi Dimitrov Mausoleum

- National Monument in Vitkov

- Mustafa Kemal Atatürk's Mausoleum

- Mausoleum of Ruhollah Khomeini

- Raj Ghat

- Mazar-e-Quaid

- Bourguiba mausoleum

- Türkmenbaşy Ruhy Mosque

- Artigas Mausoleum

- Martyrs' Mausoleum, Yangon

- Leninism

- Marxism–Leninism

References

- Gwendolyn Leick (15 November 2013). Tombs of the Great Leaders: A Contemporary Guide. Reaktion Books. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-78023-226-3.

- Tumarkin, Nina (1997). Lenin Lives! The Lenin Cult in Soviet Russia (enlarged ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 180, 191–194. ISBN 978-0-674-52431-6.

- SLEZKINE, YURI (2017-08-07). The House of Government. Princeton University Press. pp. 409–410. doi:10.2307/j.ctvc77htw. ISBN 978-1-4008-8817-7.

- "Усыпальница вождя: Мавзолей Ленина в архивных кадрах". RIA Novosti (in Russian). 2 November 2017. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- Abramov, A.; Абрамов, Алексей Сергеевич. (2005). Pravda i vymysly o kremlevskom nekropole i Mavzolee. Ėksmo. Moskva. ISBN 5-699-10822-X. OCLC 61137505.

- Romani︠u︡k, Sergeĭ; Романюк, Сергей (2013). Serdt︠s︡e Moskvy : ot Kremli︠a︡ do Belogo goroda. Moskva. ISBN 978-5-227-04778-6. OCLC 900164001.

- "Усыпальница вождя: Мавзолей Ленина в архивных кадрах". РИА Новости (in Russian). 2017. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - SLEZKINE, YURI (2017-08-07). The House of Government. Princeton University Press. p. 410. doi:10.2307/j.ctvc77htw. ISBN 978-1-4008-8817-7.

- Zbarsky, Ilya; Hutchinson, Samuel (1999). Lenin's Embalmers. Harvill Press. p. 215. ISBN 1-86046-515-3.

- Milton 2015, p. 8"...the corpse was immersed for many weeks in a special solution that contained glycerol and acetate..."

- Milton, Giles (26 March 2015). When Lenin Lost His Brain: Fascinating Footnotes from History. Hodder & Stoughton. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-4736-0890-0.

- Mark McDonald (1 March 2004). "Lenin Undergoes Extreme Makeover". Associated Press. Retrieved 19 April 2010. (alternative url Archived 2010-07-04 at the Wayback Machine)

- "На сохранение тела Ленина в 2016 году истратят более 13 млн рублей" [More than 13 million rubles will be spent on preserving Lenin's body in 2016]. News Ru (in Russian). December 6, 2017. Retrieved September 23, 2022.

- "Visiting the Diamond Fund, the Grand Kremlin Palace and Lenin's Mausoleum". www.kreml.ru. Retrieved 2020-06-28.

- "Расписание работы Мавзолея В.И. Ленина" [Opening hours of the Mausoleum of V.I. Lenin] (in Russian). Federal Protective Service (Russia). Archived from the original on 2019-04-23. Retrieved 2017-12-06.

- See, e.g., a statement by President Putin in Sankt-Peterburgsky Vedomosty, July 19, 2001.

- "Депутат предложил заменить тело Ленина в Мавзолее копией". 2018-11-14.