Madame du Barry

Jeanne Bécu, Comtesse du Barry (19 August 1743 – 8 December 1793) was the last maîtresse-en-titre of King Louis XV of France. She was executed, by guillotine, during the French Revolution due to accounts of treason—particularly being suspected of assisting émigrés flee from the Revolution.

Jeanne Bécu | |

|---|---|

| Countess of Barry | |

Portrait by Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, 1782.

Note: The head in this portrait has been edited some time after it was painted, with another artist adding rouge on du Barry's cheeks while the portrait was in the ownership of its commissioner, the Duc de Brissac. In truth, du Barry never wore rouge. | |

| Born | Jeanne Bécu 19 August 1743 Vaucouleurs, Kingdom of France |

| Died | 8 December 1793

(aged 50) Paris, French First Republic |

| Buried | Madeleine Cemetery |

| Spouse | Comte Guillaume du Barry

(m. 1768) |

In order for the king to take Jeanne as a maîtresse-en-titre, she had to be married to someone of high rank so she could be allowed at court; she was hastily married on 1 September 1768, to Comte Guillaume du Barry. The marriage ceremony was accompanied by a false birth certificate, created by Jean du Barry. The certificate made Jeanne younger by three years and dissimulated her “poor” background. Henceforth, she was deemed as an official maîtresse-en-titre to the king.[1]

Her arrival at the French royal court was considered scandalous by some, as she had been a prostitute and a commoner. For these reasons, she was disliked by many, including Marie Antoinette. Marie Antoinette's disfavoring Jeanne and refusing to speak to her was seen as a major issue within the royal court and had to be resolved. In New Year's Day 1772, Marie Antoinette remarked to Jeanne, “There are many people at Versailles today.”[2] This little interaction pleased both Jeanne and the royal court, and the dispute ended, though the latter still disapproved of Jeanne thereafter.

During the Reign of Terror, a subpart of the French Revolution, Jeanne was imprisoned due to accounts of treason, the claims being made by her page Zamor. Soon after her imprisonment, she was executed—by guillotine—on 8 December 1793. Her body was buried in the Madeleine cemetery. The gems she had smuggled out of France during the Revolution were found due to her confession, and were sold at in auction in 1795.

Early years

Jeanne Bécu was the illegitimate daughter of Anne Bécu—a 30-year-old seamstress.[3][4] Jeanne’s father is unidentified; however, it is possible that her father is Jean Jacques Gomard—a friar given the moniker frère Ange.[5] One of her mother’s acquaintances, and presumed brief lover, Monsieur Billiard-Dumonceaux, took 3-year-old Jeanne and her mother into his care when they traveled from Vaucouleurs to Paris. There, Anne was placed as a cook in his own mistress’s household. Jeanne was well-liked by Monsieur Dumonceaux's mistress Francesca, who pampered Jeanne in grandeur. Jeanne’s education began at a convent, named Couvent de Saint Aurea.[6]

At the age of fifteen, Jeanne left the Couvent, for she had “come of age”. Around that time, Jeanne and her mother were evicted from Monsieur Dumonceaux's household, and were to live at the small household of Anne’s husband, Nicolas Rançon. What caused the eviction is unknown, though it could possibly be due to Francesca’s jealousy of Jeanne's beauty and youth, or Monsieur Dumonceaux’s passion for Anne revived.

Upon this, Jeanne needed to find some sort of income to stabilise herself, and thus traveled the streets of Paris carrying a box full of trinkets for sale. Over time she worked at different occupations; she was first offered a post as an assistant to a young hairdresser named Lametz. Jeanne had a brief relationship with him that may have produced a daughter, although it is highly improbable.[7] Jeanne was soon employed as a dame de compagnie (companion) to an elderly widow, Madame de la Garde, but was sent away when her presence began to meddle in the marital affairs of both Madame de la Garde's two sons. Later, Jeanne worked as a milliners assistant as a grisette in a haberdashery shop named 'À la Toilette', which was owned by a certain Madame Labille and run by her husband. Labille's daughter, Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, became a good friend of Jeanne.

As reflected in art from the time, Jeanne was a remarkably attractive blonde woman with thick golden ringlets and almond-shaped blue eyes. Her beauty came to the attention of Jean-Baptiste du Barry, whose brother, Comte Guillaume du Barry, owned a casino. Jeanne soon came to his attention in 1763, when she was entertaining in Madame Quisnoy's brothel-casino.[8] Guillaume du Barry installed her in his household and made her his mistress. Giving her the appellation of Mademoiselle Lange, Guillaume helped establish Jeanne's career as a courtesan in the highest circles of Parisian society; this enabled her to take several aristocratic men as brief lovers or clients.[9]

Mistress of Louis XV: 1768–1774

Jeanne quickly became a sensation in Paris, building up a large aristocratic clientele. She had many lovers; from King Louis XV of France’s ministers to his own courtiers,[10] the most prominent being Maréchal de Richelieu. Due to this, Jean du Barry saw her to be holding influence over Louis XV, who became aware of her in 1768 while she was visiting Versailles. The errand involved the Duc de Choiseul, who found her rather ordinary in contrast to what most men thought of her. The king took a great interest in her and obtained her identity with the help of his personal valet and procurer Dominique Guillaume Lebel. Jeanne was escorted to the royal boudoir frequently, and it was soon becoming a worrying issue to Lebel when this liaison was seemingly becoming more than just a passing fling. In any case, Jeanne could not qualify as a maîtresse-en-titre unless she had a title; however, after divulging with the king that Jeanne was nothing but a harlot, the king ordered that Jeanne be wedded to a man of strong lineage so she may be brought to court as per protocol. This was solved by her marriage on 1 September 1768 to Jean du Barry's brother, Comte Guillaume du Barry. The marriage ceremony included a false birth certificate created by Jean du Barry himself, making Jeanne younger by three years and of fictitious noble descent.[11]

Jeanne was now installed above the king's quarters in Lebel's former rooms. She lived a lonely life, unable to be seen with the king since no formal presentation had taken place. Very few, if any, of the nobility at court deigned to become acquainted with her, for none could accept the fact that a woman of the street had the audacity to converse and intermingle with those above her station, and thrive in trying to become like them. Comte du Barry constantly pestered Jeanne and urged her to speak of presentation with the king. Louis XV, in return, asked her to find a proper sponsor to be able to have one. Richelieu took responsibility of doing so, and after a few women were approached, and asked too high of a price to take the role, her official sponsor, Madame de Béarn, was found after having her huge gambling debts paid off.

On the first occasion when the presentation was to take place, Madame de Béarn was panicked by fear and feigned a sprained ankle. On a second occasion, the king was badly hurt when he fell off his horse during a hunt and broke his arm. Finally, Jeanne was presented to the Court at Versailles on 22 April 1769; an occasion which was long-awaited for by the gathering crowds outside the palace gates, and by the gossiping courtiers within the Hall of Mirrors. Jeanne was described as wearing a silvery white gown brocaded with gold—the gown was bedecked in jewels sent by the king the night before, and had huge panniers at the sides. The dress had been specifically ordered by Richelieu for Jeanne; many courtiers claimed that it was never seen before. Her coiffure was also noticeably spectacular, being the cause of her late arrival.

Jeanne first befriended Claire Françoise, who was brought from Languedoc by her brother Jean du Barry to accompany her then-friendless sister-in-law, being also a means of companionship and a “tutor”, in which she was to help Jeanne let go of her past and take a more court-like demeanour. Later on, she also befriended the Maréchale de Mirepoix. Other women of nobility were bribed into forming her entourage.

Jeanne quickly accustomed herself to living in luxury, to which she had already been somewhat introduced whilst living with Monsieur Dumonceaux. Louis XV had also given her a young Bengali slave named Zamor, whom she dressed in elegant clothing to show him off. Jeanne developed a liking for Zamor and began to educate him.[12][13]

According to Stanley Loomis’ biography Du Barry, Jeanne's everyday routine began at 9.a.m, when Zamor would bring her a morning cup of chocolate. She would then be dressed in a fine gown of her choice and dressed in her jewellery. Accordingly, either hairdresser Nokelle for special occasions or Berline for everyday styles, would come to do her hair in powders and curls. She would then receive friends, dressmakers, jewellers and artists showing off their new stock, hoping she would be interested in buying something of their offers. She was indeed extravagant, but her good nature was not spoiled. When the old Comte and Comtesse de Lousene were forcibly evicted from their château due to heavy debts, they were sentenced to beheading because the comtesse had shot dead a bailiff and a police officer while resisting.[14] To their great fortune, they were good friends with Madame de Béarn, who told Jeanne of their situation. Though warned by Richelieu of her possible failure, she asked the king to pardon them, refusing to rise from her kneeling posture if he did not accept her request. Louis XV was astounded and his heart thawed, to which he said, "Madame, I am delighted that the first favour you should ask of me should be an act of mercy!"[15] A second similar act happened when Jeanne was visited by a certain Monsieur Mandeville, who asked pardon in the name of a young girl condemned to the gallows: she had been convicted of infanticide for giving birth to a stillborn and not informing the authorities. Jeanne wrote a letter to the Chancellor of France, who granted the pardon.

Jeanne was a tremendous triumph. She now wore extravagant gowns of great proportions both in creation and cost, exhausting the treasury all the more.[17] With diamonds covering her delicate neck and ears, she was now the king's maîtresse déclarée. Due to her new position at Court, she made both friends and enemies. Her most bitter rival was the Duchesse de Gramont, who had in vain tried her best to acquire the place of the late Marquise de Pompadour, and according to Diane Adélaïde de Mailly, Béatrix de Gramont would have disdained the comtesse no matter what.[18] She had, since the beginning, plotted with her brother for the removal of Jeanne, even going to the extent of slandering her name as well as the king's on gutter pamphlets.

In time Jeanne became acquainted with the Duc d’Aiguillon, who sided with her against the opposing Duc de Choiseul. As Jeanne's power in court grew stronger, Choiseul began feeling his was waning, and against the king's wishes after the terrible Seven Years' War incident, he decided France was capable of war again and sided with the Spanish against the British for possession of the Falkland Islands. When this plot came to light to the du Barry clan, the mistress exposed all to the king and, in Christmas Eve 1771, Choiseul was dismissed of his ministerial role from court, which was ordered by His Majesty. He then went into exile at his Chanteloup property, alongside his wife and sister.

While Jeanne was part of the faction that brought down the Duc de Choiseul,[19] she was unlike her late predecessor, Madame de Pompadour, in the fact that she had little interest in politics,[20] preferring rather to pass her time ordering new ravishing gowns and complementary jewellery, however, the king went so far as to let her participate in state councils.[21] A note in a modern edition of the Souvenirs of Mme. Campan recalls an anecdote: the king said to the Duc de Noailles that, with Madame du Barry, he had discovered new pleasures; "Sire" – answered the duke – "that's because your Majesty has never been in a brothel."[22] While Jeanne was known for her good nature and support of artists, she grew increasingly unpopular because of the king's financial extravagance towards her. She was forever in debt despite her huge monthly income from the king—at one point she was given three hundred thousand livres.[23]

She remained in her position until the death of the king, and the attempt to depose her made by the Duc de Choiseul and the Duc de Aiguillon by trying to arrange a secret marriage between the king and Madame Pater proved unsuccessful.[24]

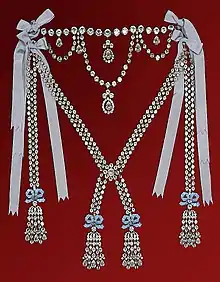

Diamond necklace affair

In 1772, the infatuated Louis XV requested that Parisian jewellers Boehmer and Bassenge create an elaborate and spectacular jeweled necklace for Jeanne—one that would surpass all known others in extravagance—at an estimated cost of two million livres.[25] The necklace, still not completed nor paid for when Louis XV died, would eventually trigger a scandal involving Jeanne de la Motte-Valois, in which Queen Marie Antoinette[26] would be accused of bribing the Cardinal de Rohan to purchase it for her, accusations which would figure prominently in the onset of the French Revolution.[27]

Exile: 1774–1792

In time, King Louis XV started to show his age by constantly thinking of death and repentance, and began missing appointments in Jeanne's boudoir.[28] During a stay at the Petit Trianon with her, Louis felt the first symptoms of smallpox. He was brought back to the palace at night and put to bed, where his three daughters—including Jeanne—stayed beside him. On 4 May 1774, the king suggested to Madame du Barry that she leave Versailles, both to protect her from infection and so that he could prepare for confession and last rites.[29] She was relieved of her duties by Doctor Lemonnier and immediately retired to the Duc d'Aiguillon's estate near Rueil, as were his wishes. Following the death of Louis XV and his grandson's ascension to the throne, Marie Antoinette had her husband exile Jeanne to the Abbey du Pont-aux-Dames near Meaux-en-Brie.[30] At first she was not met warmly by the nuns, who knew that in their midst they had the 31-year-old former royal mistress, but soon enough they grew accustomed to her timid ways and opened up to her, most of all the abbess Madame de la Roche-Fontenelle.

After a year at the convent, Jeanne was granted permission to visit the surrounding countryside on one condition: she returned by sundown. A month later, she was given permission to leave the abbey but not to venture closer than ten miles towards Versailles, thus cancelling her idea of going to her beloved Château de Louveciennes. She then managed to purchase property belonging to the family of the wife of Madame de la Garde's younger son, whom she knew from her earlier years. Two years later, she moved to the Louveciennes.[31]

In the following years, she had a liaison with Louis Hercule Timoléon de Cossé-Brissac.[32] She later also fell in love with Henry Seymour of Redland,[33] whom she met when he moved with his family to the neighbourhood of the Château. In time, Seymour became fed up with his secret love affair and sent a painting to Jeanne with the words 'leave me alone' written in English at the bottom, which the painter Lemoyne copied in 1796. The Duc de Brissac proved the more faithful in this ménage-a-trois, having kept Jeanne in his heart even though he knew of her affair with Seymour.

During the French Revolution, Brissac was captured while visiting Paris, and was slaughtered by a mob. Late one night, Jeanne heard the sound of a small drunken crowd approaching the Château, and into the opened window where she looked out someone threw a blood-stained cloth.[34] To Jeanne's horror, it contained Brissac's head, at which sight she fainted.

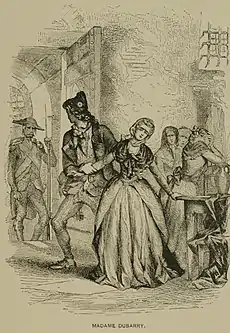

Imprisonment, trial and execution: 1792–93

Jeanne’s Bengali slave Zamor, along with another member of du Barry's domestic staff, had joined the Jacobin club. He became a follower of the revolutionary George Grieve and then an office-bearer in the Committee of Public Safety. Jeanne found out about this and questioned Zamor about his connections with Grieve. Upon realising the depth of his involvement, she gave him three days’ notice to quit her service. This Zamor did without hesitation, and promptly proceeded to denounce his mistress to the Committee.

Based largely on Zamor's testimony, Madame du Barry was suspected of financially assisting émigrés who had fled the French Revolution. The denunciation by Zamor happened in 1792, and Madame du Barry was finally arrested in 1793. In 1792, when the Revolutionary Tribunal of Paris accused her of treason and condemned her to death, she vainly attempted to save herself by revealing the location of the gemstones she had hidden.[35] During the ensuing trial, Zamor gave Chittagong as his birthplace; he was likely of Siddi origin. His testimony, along with that of many others, sent the comtesse to the guillotine.

On 8 December 1793, Madame du Barry was beheaded by the guillotine on the Place de la Révolution. On the way to the guillotine, she collapsed in the tumbrel and cried, "You are going to hurt me! Why?!" Terrified, she screamed for mercy and begged the watching crowd for help. Her last words to the executioner are said to have been: «De grâce, monsieur le bourreau, encore un petit moment!» - "One more moment, Mr. Executioner, I beg you!" She was buried in the Madeleine Cemetery, like many others executed during the Reign of Terror, including Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette.

Although her French estate went to the Tribunal de Paris, the jewels she had smuggled out of France to England were sold at an auction at Christie's in London, in 1795. Colonel Johann Keglevich, a brother of Major General Stephan Bernhard Keglevich, took part in the Battle of Mainz in 1795 with Hessian mercenaries, who were financed by the British Empire with the money from this sale.

Relationship with Marie Antoinette

Jeanne’s relationship with Marie Antoinette was contentious. The first meeting of the two was during a family supper at the Château of La Muette, on 15 May 1770—the day before Marie Antoinette’s wedding with Louis-Auguste. Jeanne had only been a mistress for little over a year, and many thought she would not be included in the list of guests for the occasion.[36] It ended up being otherwise, to the disgust of most of those present. Marie Antoinette noticed Jeanne, who stood out from the rest of the crowd with her extravagant appearance and a high talkative voice. The comtesse de Noailles informed Marie Antoinette that the role of Jeanne was to give pleasure to the king, and the 14-year-old archduchess added that she would thus be her rival at such role. The Comte de Provence soon after divulged the true nature of such pleasure, causing instant hatred in Marie Antoinette towards Madame du Barry for such immorality. This rivalry kept on for quite some time, especially since the dauphine supported Choiseul as the proponent of the alliance with Austria. Marie Antoinette defied court protocol by refusing to speak to Madame du Barry, owing not only to her disapproval of the latter's background, but also after hearing from the Comte de Provence of du Barry's amused reaction to a story told by the Cardinal de Rohan during one of her dinner parties, in which Marie Antoinette's mother, Empress Maria Theresa, was slandered, adding therefore yet another foe to her list.[37]

Jeanne furiously complained to the king, who then complained to the Austrian ambassador Mercy, who in turn did his best in convincing Marie Antoinette to ease her ways. Eventually, during a ball on New Year's Day 1772, Marie Antoinette spoke indirectly to Jeanne by casually observing; "There are many people at Versailles today,”[38][2] giving her the option to respond or not.

In popular culture

Food

Many dishes, such as Soup du Barry, are named after Jeanne. All dishes "du Barry" have a creamy white sauce, and many have cauliflower in them. The cauliflower may be an allusion to her powdered wigs, which had curls piled high on top of each other like cauliflower florets.[39]

Film

Madame du Barry was portrayed in film by:

- Mrs. Leslie Carter in the 1915 film DuBarry, directed by Edoardo Bencivenga

- Theda Bara in the 1917 film Madame Du Barry, directed by J. Gordon Edwards

- Pola Negri in the 1919 film Madame DuBarry, directed by Ernst Lubitsch

- Norma Talmadge in the 1930 film Du Barry, Woman of Passion

- Dolores del Río in the 1934 film Madame Du Barry, directed by William Dieterle

- Gladys George in the 1938 MGM film Marie Antoinette, which starred Norma Shearer in the title role

- Lucille Ball in the 1943 movie version of DuBarry Was a Lady

- Margot Grahame in the 1949 film Black Magic; it also starred Orson Welles in the lead role of Count Cagliostro

- Martine Carol in the 1954 film Madame du Barry, directed by Christian-Jaque

- Asia Argento in the 2006 film Marie Antoinette, directed by Sofia Coppola

- Maïwenn in the 2023 film La Favorite; also starring Johnny Depp as Louis XV, directed by Maïwenn

Literature

- In The Idiot, by Fyodor Dostoyevsky, the character Lebedev tells the story of her life and execution and prays for her soul, among other souls.[40]

- Du Barry is one of the central characters in Sally Christie's The Enemies of Versailles (2017).

Television

- Du Barry is portrayed by Japanese voice actress Ryoko Kinomiya in the anime The Rose of Versailles, as a villainous, scheming enemy of Marie Antoinette; her struggles with the young princess are a major concern of the story in its early stages.

Opera

- Gräfin Dubarry is an operetta in three acts by Carl Millöcker to a German libretto by F. Zell and Richard Genée.

References

- Citations

- Kelley, Jan (7 December 2012). "A Mistress's Tale". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- Kuckhahn, Geni (8 May 2019). "Madame du Barry vs Marie Antoinette". Geni Kuckhahn. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- "Family tree of Anne BECU de CANTIGNY". Geneanet. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- Haslip 1992.

- Plaidy 2007, p. 302.

- Haslip 1992, p. 3.

- Haslip 1992, p. 6.

- Stoeckl 1966, p. 23.

- Haslip 1992, p. 16. Such reference is made in the sentence that Jeanne was a talented courtesan, whom sometimes “[Jean] du Barry regretted when necessity forced him to merchandise what he would willingly have kept for himself”, obviously indicating that Jeanne (who was well aware of her beauty and sexual charms) was had very good means, whereby he could climb the ladder of success. She is referred to many times in books as a courtesan, which in common language means a high-class prostitute (though by no means should one think that she was a common soliciting streetwalker).

- Herman, An Indecent Pitch of Luxury as to Insult the Poverty of the People, p.175

- Haslip 1992, p. 27.

- Caroline Weber (19 September 2006). Queen of Fashion. Internet Archive. Henry Holt and Co. ISBN 978-0-8050-7949-4.

- Bose, Arghya. "How an Indian man taken to Europe as a slave played a role in the French Revolution". Scroll.in. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- Stoeckl 1966, p. 43.

- Loomis 1959, pp. 55–56.

- "Jeanne Bécu, Comtesse du Barry". Madame Guillotine. 2 May 2020. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- Haslip 1992, p. 32: "The carriages, jewels....reclaim the money from the royal treasury."

- Grey, Juliet (2011). Becoming Marie Antoinette. Ballantine Books. p. 322. ISBN 9780345523860.

- Langon, Baron Etienne Leon Lamothe (2010). Memoirs of the Comtesse Du Barry; with intimate details of her entire career as favorite of Louis XV. Chapter XXV: Kessinger Publishing. p. 234.

- Baumgold, Julie (2005). The Diamond: A Novel. Simon and Schuster. p. 136. ISBN 9780743274548.

- Mme. Campan, Souvenirs

- Herman 2004, p. 22.

- Herman, Pensions, p.146

- Fleury 1909.

- "The Diamond Necklace Affair". Marie Antoinette Online. 11 January 2009. Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- Herman, Jewels, p.135

- Catherine Temerson, Evelyne Lever (2000). Marie Antoinette: The Last Queen of France. Chapter 21-The Diamond Necklace Affair: St. Martin's Griffin. pp. 173–182. ISBN 9780312283339.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Haslip 1992, p. 81: "She never dared go out for long,...rest for a while in peace"

- "newadvent.org".

- Bernier 1984, pp. 246–249.

- Herman 2004, p. 203.

- Haslip 1992, p. 133.

- Haslip 1992, p. 121.

- Smee, Sebastian. "This gorgeous portrait is haunted by intrigue and death". Washington Post. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- Stoeckl 1966, p. 174.

- "Madame du Barry: From Prostitute to King Louis XV's Last Mistress, and Died as Famous Victim of the French Revolution | Feature Series | THE VALUE | Art News". TheValue.com. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- Haslip 1992, p. 78: "Prince de Rohan had made fun of the pious old Empress... No one, it appears, had laughed so heartily as the hostess"

- Palache 2005, p. 28.

- Madison, Deborah (26 January 2017). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Fruits, Vegetables, and Herbs: History, Botany, Cuisine. Book Sales. pp. 170–. ISBN 978-0-7858-3488-5.

- Fyodor Dostoyevsky (July 2003). The Idiot. Vintage Books. pp. 196–198. ISBN 978-0-375-70224-2.

- Bibliography

- Antoine, Michel (1989). Louis XV (in French). Paris: Librairie Arthème Fayard. ISBN 9782010178184.

- Bernier, Oliver (1984). Louis the Beloved: The Life of Louis XV. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company. ISBN 0-385-18402-6.

- Castelot, André. (1989). Madame du Barry. Paris: Perrin. ISBN 9782262006914.

- Fleury, comte Maurice (1909). Louis XV intime et les petites maitresses (in French). Paris: Plon.

- Haslip, Joan (1992). Madame du Barry: The Wages of Beauty. New York: Grove Weidenfeld. ISBN 978-0-8021-1256-9.

- Herman, Eleanor (2004). Sex with Kings: 500 Years of Adultery, Power, Rivalry, and Revenge. New York: Morrow. ISBN 0-06-058544-7.

- La Croix de Castries, René de (1967). Madame du Barry (in French). Paris: Hachette.

- Loomis, Stanley (1959). Du Barry: A Biography. Philadelphia: Lippincott.

- Palache, John Garber (2005). Marie Antoinette The Player Queen. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 9781417902507.

- Saint-André, Claude (1915). A King's Favourite, Madame du Barry, and her times from hitherto unpublished documents. New York: McBride, Nast. translated from the French Madame du Barry, published by Tallandier, Paris, 1909.

- Saint-Victor, Jacques de (2002). Madame du Barry: un nom de scandale (in French). Paris: Perrin. ISBN 9782262016616.

- Stoeckl, Agnes, (Baroness de) (1966). Mistress of Versailles: The Life of Madame du Barry. London: John Murray.

- Vatel, Charles (1883). Histoire de madame du Barry (in French). Paris: L. Bernard.

External links

- Madame du Barry at Château de Versailles

- Full text of Memoirs of the Comtesse Du Barry from Project Gutenberg

- Catherine Delors: Madame du Barry returns to Versailles

- Jeanne Bécu, Countess du Barry at Unofficial Royalty