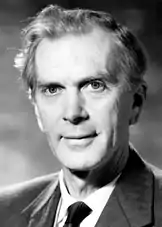

Martin Ryle

Sir Martin Ryle FRS[4] (27 September 1918 – 14 October 1984) was an English radio astronomer who developed revolutionary radio telescope systems (see e.g. aperture synthesis) and used them for accurate location and imaging of weak radio sources. In 1946 Ryle and Derek Vonberg were the first people to publish interferometric astronomical measurements at radio wavelengths. With improved equipment, Ryle observed the most distant known galaxies in the universe at that time. He was the first Professor of Radio Astronomy in the University of Cambridge and founding director of the Mullard Radio Astronomy Observatory. He was the twelfth Astronomer Royal from 1972 to 1982.[5] Ryle and Antony Hewish shared the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1974, the first Nobel prize awarded in recognition of astronomical research.[6] In the 1970s, Ryle turned the greater part of his attention from astronomy to social and political issues which he considered to be more urgent.

Sir Martin Ryle FRS | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 27 September 1918 Brighton, England |

| Died | 14 October 1984 (aged 66) Cambridge, England |

| Education | Bradfield College |

| Alma mater | University of Oxford (BA, DPhil) |

| Known for | Aperture synthesis Radio astronomy |

| Spouse | Rowena Palmer (m. 1947) |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Astronomy |

| Institutions |

|

| Doctoral advisor | J. A. Ratcliffe[1] |

| Doctoral students | Malcolm Longair[1][2] Peter Rentzepis Jan Högbom[3] John E. Baldwin |

Education and early life

Martin Ryle was born in Brighton, England, the son of Professor John Alfred Ryle and Miriam (née Scully) Ryle. He was the nephew of Oxford University Professor of Philosophy Gilbert Ryle. After studying at Bradfield College, Ryle studied physics at Christ Church, Oxford. In 1939, Ryle worked with the Telecommunications Research Establishment (TRE) on the design of antennas for airborne radar equipment during World War II. After the war, he received a fellowship at the Cavendish Laboratory.

Career and research

The focus of Ryle's early work in Cambridge was on radio waves from the Sun.[7][8][9][10] His interest quickly shifted to other areas, however, and he decided early on that the Cambridge group should develop new observing techniques. As a result, Ryle was the driving force in the creation and improvement of astronomical interferometry and aperture synthesis, which paved the way for massive upgrades in the quality of radio astronomical data. In 1946 Ryle built the first multi-element astronomical radio interferometer.[11]

Ryle guided the Cambridge radio astronomy group in the production of several important radio source catalogues. One such catalogue, the Third Cambridge Catalogue of Radio Sources (3C) in 1959 helped lead to the discovery of the first quasi-stellar object (quasar).

While serving as university lecturer in physics at Cambridge from 1948 to 1959, Ryle became director of the Mullard Radio Astronomy Observatory in 1957 and professor of radio astronomy in 1959. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1952,[4] was knighted in 1966 (p 519 of[4]) and succeeded Sir Richard Woolley as Astronomer Royal from 1972 to 1982. Ryle and Antony Hewish shared the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1974, the first Nobel prize awarded in recognition of astronomical research. In 1968 Ryle served as professor of astronomy at Gresham College, London.

Personality

According to numerous reports Ryle was quick-thinking, impatient with those slower than himself and charismatic (pp 502, 508, 510 of[4]). He was also idealistic (p 519 of[4]), a characteristic he shared with his father (p 499 of,[4][12]). In an interview (p271 of[13]) in 1982 he said "At times one feels that one should almost have a car sticker saying 'Stop Science Now' because we're getting cleverer and cleverer, but we do not increase the wisdom to go with it."

He was also intense and volatile (p 327 of[14]), the latter characteristic being associated with his mother (p 499 of,[4] Folder A.20 of[12]). The historian Owen Chadwick described him as "a rare personality, of exceptional sensitivity of mind, fears and anxieties, care and compassion, humour and anger." (Folder A.28 of[12])

Ryle was sometimes considered difficult to work with – he often worked in an office at the Mullard Radio Astronomy Observatory to avoid disturbances from other members of the Cavendish Laboratory and to avoid getting into heated arguments, as Ryle had a hot temper. Ryle worried that Cambridge would lose its standing in the radio astronomy community as other radio astronomy groups had much better funding, so he encouraged a certain amount of secrecy about his aperture synthesis methods in order to keep an advantage for the Cambridge group. Ryle had heated arguments with Fred Hoyle of the Institute of Astronomy about Hoyle's steady state universe, which restricted collaboration between the Cavendish Radio Astronomy Group and the Institute of Astronomy during the 1960s.

War, peace and energy

Ryle was a new physics graduate and an experienced radio ham in 1939, when the Second World War started. He played an important part in the Allied war effort,[4] working mainly in radar countermeasures. After the war, "He returned to Cambridge with a determination to devote himself to pure science, unalloyed by the taint of war."[4]

In the 1970s, Ryle turned the greater part of his attention from astronomy to social and political issues which he considered to be more urgent. With publications from 1976 and continuing, despite illness[4] until he died in 1984, he pursued a passionate and intensive program on the socially responsible use of science and technology.[15] His main themes were:

- Warning the world of the horrific dangers of nuclear armaments, notably in his pamphlet Towards the Nuclear Holocaust.[16]

- Criticism of nuclear power, as in Is there a case for nuclear power?[17]

- Research and promotion of alternative energy and energy efficiency, as in Short-term Storage and Wind Power Availability.[18]

- Calling for the responsible use of science and technology. "...we should strive to see how the vast resources now diverted towards the destruction of life are turned instead to the solution of the problems which both rich - but especially the poor - countries of the world now face."[15]

In 1983 Ryle responded to a request from the President of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences for suggestions of topics to be discussed at a meeting on Science and Peace. Ryle's reply was published posthumously in Martin Ryle's Letter.[15] An abridged version appears in New Scientist with the title Martin Ryle's Last Testament.[19] The letter ends with "Our cleverness has grown prodigiously – but not our wisdom."

Honours and awards

Ryle was awarded numerous prizes and honours including:

- Elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1952[4]

- Hughes Medal (1954)

- Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society (1964)[20]

- Fernand Holweck Medal and Prize (1965)

- Henry Draper Medal of the National Academy of Sciences (1965)[21]

- Albert A. Michelson Medal of the Franklin Institute (1971)[22]

- Royal Medal (1973)

- Bruce Medal (1974)[23]

- Nobel Prize in Physics (1974)

- Ryle Telescope at Mullard Radio Astronomy Observatory

- In 1965 Ryle co-delivered the Royal Institution Christmas Lecture on Exploration of the Universe.

Personal life

In their early years Martin and his elder brother received lessons at home in carpentry (p 498 of [4]) and manual skills became important for him throughout his life. This was for relaxation – he built boats to his own designs (p 498 of [4]) – and professionally. In his wartime radar work ([24]), his post-war radio-telescope building (p 510 of [4]) and his late researches into wind energy (p 517 of [4]) he was a hands-on practical engineer as well as a scientist.

Ryle also had a lifelong interest in sailing (p 498 of[4]) and this matched his choice when in the 1970s he turned his research subject from astronomy to wind energy (pp 420–422 of[25])

Another practical skill acquired by Martin in youth that later served him well in his professional career was as a radio 'ham'. While still at School (Bradfield College) he built his own transmitter and obtained a Post Office licence to operate it (pp 498–499 of[4]), with the GB-Callsign G3CY.

In 1936 the family moved to a house in Cambridge which became Martin's home after the war. In 1947 he and Rowena Palmer married and they lived in this house for rest of Martin's life. They had three children, born in 1949, 1951 and 1952. Ryle died on 14 October 1984, in Cambridge. He was celebrated on a first class stamp issued in 2009 as part of an Eminent Britons set.[26] Lady Ryle died in 2013.[27]

Ryle was an amateur radio operator,[4] and held the GB-Callsign G3CY.

References

- Martin Ryle at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- Longair, Malcolm Sim (1967). The evolution of radio galaxies. lib.cam.ac.uk (PhD thesis). University of Cambridge. OCLC 657635513. EThOS uk.bl.ethos.648088.

- Högbom, Jan A. (1959). The structure and magnetic field of the solar corona. cam.ac.uk (PhD thesis). University of Cambridge.

- Graham-Smith, Francis (1986). "Martin Ryle. 27 September 1918 – 14 October 1984". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. Royal Society. 32: 496–524. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1986.0016. S2CID 71422161.

- About Sir Martin Ryle

- Press release about Martin Ryle's Nobel Prize.

- Martin Ryle publications indexed by the Scopus bibliographic database. (subscription required)

- Obs 104 (1984) 283

- QJRAS 26 (1985) 358

- The Papers of Martin Ryle have been catalogued by Anna-K Mayer and Tim Powell, NCUACS, in 2009 and are deposited with the Churchill Archives Centre, Cambridge.

- Ryle, M.; Vonberg, D. D. (1946). "Solar Radiation on 175 Mc./s". Nature. 158 (4010): 339. Bibcode:1946Natur.158..339R. doi:10.1038/158339b0. S2CID 4097569. – Observations from the first multi-element astronomical radio interferometer

- The Papers of Sir Martin Ryle at Churchill Archives Centre

- Williams R ed The Best of The Science Show. Nelson, 1983.

- Kragh, H. Cosmology and Controversy: the historical development of two theories of the universe. Princeton University Press, 1996.

- Rowan-Robinson, M. and Rudolf, A. (1985) Martin Ryle's Letter. Menard Press.

- Ryle, M. Towards the Nuclear Holocaust. Menard Press, 1981.

- Ryle, M (1981). "Is there a case for nuclear power?". Electronics and Power. 28 (7/8): 496–500. doi:10.1049/ep.1982.0267.

- Anderson, M. B.; Newton, K.; Ryle, M.; Scott, P. F. (1978). "Short-term Storage and Wind Power Availability". Nature. 275 (5679): 432–434. Bibcode:1978Natur.275..432A. doi:10.1038/275432a0. S2CID 4266229.

- Ryle M. (1985) "Martin Ryle's Last Testament". New Scientist 105 (14 February): 36-37.

- "Winners of the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society". Royal Astronomical Society. Archived from the original on 25 May 2011. Retrieved 24 February 2011.

- "Henry Draper Medal". National Academy of Sciences. Archived from the original on 26 January 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2011.

- "Franklin Laureate Database – Albert A. Michelson Medal Laureates". Franklin Institute. Archived from the original on 6 April 2012. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- "Past Winners of the Catherine Wolfe Bruce Gold Medal". Astronomical Society of the Pacific. Archived from the original on 6 October 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2011.

- Ryle M. (1985) "D-13:some personal memories of 24th–28th May 1944". IEE Proceedings 132 (6 October): 438–440.

- Longair, M. Maxwell's Enduring Legacy: a scientific history of the Cavendish laboratory. Cambridge University Press, 2016.

- Eminent Britons stamp set

- geni.com

External links

- Martin Ryle on Nobelprize.org including the Nobel Lecture, 12 December 1974 Radio Telescopes of Large Resolving Power