Mil Mi-28

The Mil Mi-28 (NATO reporting name "Havoc") is a Russian all-weather, day-night, military tandem, two-seat anti-armor attack helicopter. It is an attack helicopter with no intended secondary transport capability, better optimized than the Mil Mi-24 gunship for the role. It carries a single gun in an undernose barbette, plus external loads carried on pylons beneath stub wings.

| Mi-28 | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| A Mi-28N of the Russian Air Force | |

| Role | Attack helicopter |

| National origin | Soviet Union/Russia |

| Manufacturer | Mil |

| First flight | 10 November 1982[1] |

| Introduction | 15 October 2009 (Mi-28N)[2] |

| Status | In service[3] |

| Primary users | Russian Air Force Algerian Air Force Iraqi Air Force |

| Produced | 1982–present |

Development

Origins

In 1972, following the completion of the Mil Mi-24, development began on a unique attack helicopter with transport capability. The new design had a reduced transport capability (3 troops instead of 8) and omitted the cabin to provide better overall performance and higher top speed. Improved performance was important for its intended role fighting against tanks and enemy helicopters and covering helicopter landing operations. Initially, many different designs were considered, including an unconventional project with two main rotors, placed with engines on tips of wings (in perpendicular layout); and in one similarity with the late 1960s-era American Lockheed AH-56 Cheyenne attack helicopter design, with an additional pusher propeller on the tail. In 1977, a preliminary design was chosen in a classic single-rotor layout. It lost its similarity to the Mi-24, and even the canopies were smaller, with flat surfaces.

Design work on the Mi-28 began under Marat Tishchenko in 1980.[4] In 1981, a design and a mock-up were accepted. The prototype (no. 012) first flew on 10 November 1982.[4] The second prototype (no. 022) was completed in 1983. In 1984, the Mi-28 completed the first stage of state trials, but in October 1984 the Soviet Air Force chose the more advanced Kamov Ka-50 as the new anti-tank helicopter. Mi-28 development continued, but given lower priority. In December 1987, Mi-28 production at Rosvertol in Rostov-on-Don was approved.

An early production Mi-24 was fitted with an air data boom as an early test for the Mi-28's technologies. Later, a few Mi-24Ds were fitted up with the Mi-28's radome mount to test the sighting-flight-navigational complex's abilities, and others had redesigned fuselages that closely resembled the future Mi-28, but with rounded cockpits.[5]

In January 1988, the first Mi-28A prototype (no. 032) flew. It was fitted with more powerful engines and an "X" type tail rotor instead of the three-blade version. The Mi-28A debuted at the Paris Air Show in June 1989. In 1991 the second Mi-28A (no. 042) was completed. The Mi-28A program was cancelled in 1993 because it was deemed uncompetitive with the Ka-50, in particular it was not all-weather capable.

.jpg.webp)

The Mi-28N was unveiled in 1995, the N designation meaning "night". The prototype (no. 014) first flew on 14 November 1996. Its most significant feature is a radar in a round cover above the main rotor, similar to that of the American AH-64D Apache Longbow. The Mi-28N also has improved tor vision and an aiming device under the nose, including a TV camera and FLIR. Due to funding problems, development was interrupted. A second prototype with an improved rotor design was unveiled in March 2004 at Rosvertol.

The first serial Mi-28N was delivered to the Army on 5 June 2006.[6][7] By 2015, 67 Mi-28Ns were planned to be purchased, when the Mi-24 was to be completely replaced.[7][8] The Rostvertol plant delivered about 140 Mi-28N and Mi-35M helicopters in 2012–14 to domestic and foreign customers; 28 helicopters were delivered in 2015.[9]

Mil also developed an export variant of the Mi-28N, designated Mi-28NE, and a simpler day helicopter variant, the Mi-28D, based on the Mi-28N design, but without radar and FLIR.

A fifth-generation derivative, dubbed Mi-28NM, has been in development since 2008. According to then chief executive officer at Russian Helicopters Andrey Shibitov, the criteria for the modernized helicopter include low-radar signature, extended flight range, advanced weapons control system, some capability of a fighter jet and speed up to 600 km/h.[10]

In 2016, Russian media reported a new, advanced helmet system designed to display visual information for aiming at targets in any field of view was under development for the MI-28N.[11]

Design

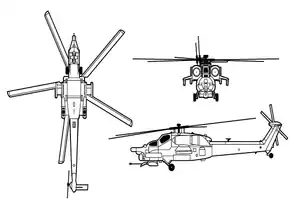

The Mi-28 is a new-generation attack helicopter that functions as an air-to-air and air-to-ground partner for the Mi-24 Hind and Ka-50 Hokum. The five-blade main rotor is mounted above the body midsection, short, wide, tapered, weapon-carrying wings are mounted to the rear of the body midsection. Two turboshaft engines in pods are mounted alongside the top of the fuselage with downturned exhausts. The fuselage is slender and tapers to the tail boom and nose. It features tandem, stepped-up cockpits, a cannon mounted beneath the belly, and a non-retractable tricycle tail-wheel type landing gear. Due to the energy-absorbing landing gear and seats the crew can survive a vertical fall of up to 12 m/s. The Mi-28 has a fully armoured cabin, including the windshield, which withstands 7.62 and 12.7 mm armor piercing bullets and 20 mm shell fragments.[12]

The helicopter design is based on the conventional pod and boom configuration, with a tail rotor. The main rotor head has elastomeric bearings and the main rotor blades are made from composite materials. The tail rotor is designed on a biplane configuration, with independently controlled X-shaped blades. A new design of all-plastic rotor blades, which can sustain 30 mm shells, is installed on the Mi-28N night attack variant.

It is equipped with two heavily armored cockpits, a windshield able to withstand 12.7–14.5 mm caliber bullets, in-nose electronics, and a narrow-X tail rotor (55 deg), with reduced noise characteristics. It is powered by two 2,200 hp Isotov TV-3-117VM (t/n 014) turboshaft engines.

While the Mi-28 is not intended for use as a transport, it does have a small passenger compartment capable of carrying three people. The planned purpose of this is the rescue of downed helicopter crews.

The Mi-28N features a helmet mounted display for the pilot. The pilot designates targets for the navigator/weapons officer, who proceeds to fire the weapons required to fulfill that particular task. The integrated surveillance and fire control system has two optical channels providing wide and narrow fields of view, a narrow-field-of-view optical television channel, and laser rangefinder. The system can move within 110 degrees in azimuth and from +13 to −40 degrees in elevation.[12]

The night attack variant helicopter retains most of the structural design of the original Mi-28. The main difference is the installation of an integrated electronic combat system. Other modifications include: new main gearbox for transmitting higher power to the rotor, new high-efficiency blades with swept-shaped tips, and an engine fuel injection control.[12]

The pilot uses a helmet-mounted target designator, which allocates the target to the navigator's surveillance and fire control system. The navigator/weapons officer is then able to employ guided weapons or guns against the target. The targeting system follows the direction of the pilot's eyes.[12]

Russia's military rotary-wing aircraft fleet has been fully refitted with new night vision goggles (NVG). Mil Mi-28N attack helicopters of the Russian Aerospace Forces (VKS) received GEO-ONV1-family NVGs.[13]

Armament

The Mi-28 is equipped with a chin-mounted NPPU-28 turret with 30 mm automatic Shipunov 2A42 autocannon.[14] It has selective fire, and a dual-feed, which allows for a cyclic rate of fire between 200 and 800 rounds per minute.[15] Its effective range varies from 1,500 meters for ground vehicles to 2,500 meters for airborne targets. Rounds from High Explosive Incendiary (HEI) to Armour-Piercing Discarding Sabot (APDS) can be used. Stated penetration for the 3UBR8 round is 25 mm of RHA at 1,500 meters.

The standard missile armament of the Mi-28N is the supersonic 9M120 Ataka-V missile, which uses radio beam-riding guidance. Two racks can each carry 8 Ataka missiles, giving a total of 16 missile, although 8 Atakas is a more normal load.[16] There are four variants of the Ataka missile for different tasks. The 9M120 Tandem High Explosive Anti-Tank (HEAT) warhead variant is used against tanks fitted with Explosive Reactive Armor (ERA), its stated penetrative ability is 800 mm Rolled Homogeneous Armour (RHA).[17] The 9M120F thermobaric variant is used against infantry, buildings, bunkers, and caves. The 9M120O expanding rod warhead variant is used against helicopters. All the variants have a range of 6 km. The 9M120M improved version has a longer range (8 km) and better penetration (900 mm of RHA).[18] All variants use SACLOS missile guidance.

Unguided weapons such as rockets can be carried on four pylons under the stub wings. Typical rockets carried are the 122 mm (4.8 in) S-13, fired from five-round B-13 rocket pods, and the 80 mm (3.1 in) S-8, fired from 20-round B8V-20 pods.[16] The S-8 and S-13 rockets used by the Mi-28 are usually unguided. In the most common configuration, one can expect 40 S-8 rockets or 10 S-13 rockets. Both rockets have their variants, from HEAT warheads to thermobaric warheads. The S-8 has a shorter range and smaller warhead than the S-13, but compensates with numbers. Currently, the Russian Air Force are upgrading their S-8 and S-13 rockets to laser guided missiles with the proposed Ugroza ("Menace") system. Rockets upgraded under Ugroza received the designations S-8Kor and S-13Kor, respectively.[19]

The Mi-28 can also carry the IR guided R-73 air-to-air missiles, the Kh-25 air-to-surface missiles as well as up to 500 kg aerial bombs.[20]

Operational history

Russia

The first production examples of the Mi-28N completed factory flight and armament tests in late May 2006, and were received by the Russian Air Force on 5 June 2006. The Mi-28N was officially accepted three years later, in October 2009.[2] It was assumed the Mi-28N would fully replace the older Mi-24 variant in the Russian Armed Forces by 2015.

In September 2011, six Mi-28Ns of the Russian Air Force took part in the 2011 Union Shield joint Russian-Belarusian military exercise at the Ashuluk training ground in Astrakhan Oblast, Russia.[2]

To improve the training of pilots for the Mi-28N, the Russian Defense Ministry announced the procurement of up to 60 Mi-28UB training-and-combat versions by 2020. Four to six Mi-28UBs would be purchased for every unit that operates the Mi-28N. An initial batch of 24 Mi-28UB training-and-combat helicopters was ordered in April 2016,[21] and the first two serial Mi-28UBs arrived at the Torzhok Air Base on 16 November 2017.[22]

During the Russian military intervention of the Syrian civil war, the Mi-28N had its combat debut during the 2016 Battle of Palmyra when several Mi-28Ns of the Russian Air Force supported the Syrian Arab Army (SAA) in their advance towards the city.[23] During their support to SAA, Russia's Mi-28Ns targeted several Islamic State positions with S-8 unguided rockets and 9M120 Ataka anti-tank guided missiles.[24][25]

In October 2016, a prototype of an upgraded Mi-28NM helicopter performed its maiden flight.[26] The Russian Defence Ministry ordered the first batch of Mi-28NM helicopters in December 2017, not disclosing the number of helicopters ordered.[27] In March 2019, a Mi-28NM prototype was seen accompanied by a Mi-24/Mi-35M during a combat sortie over rebel-held territory in the northern Hama.[28] It was reported the helicopter was sent to Syria to undergo testing in difficult weather and climate conditions.[29] The Russian Air Force received the first two serial Mi-28NMs on 23 June 2019.[30] A month later, during the International Military-Technical Forum ARMY-2019, the Russian Defence Ministry and Rostec signed a long-term contract for the supply of 98 Mi-28NMs by 2027.[31] A new contract was signed in August 2022.[32]

The Mi-28N was deployed by Russia during the 2022 invasion of Ukraine.[33] The Times reported that Ukrainian forces had successfully used a UK-made Starstreak system to shoot down a Russian Mi-28N attack helicopter in early April.[34] On 26 April, the wreck of a Mi-28 was found by Ukrainian forces outside the town of Hostomel in Kyiv region. The craft was likely destroyed during the battle for Hostomel airport.[35] On 9 May, one Mi-28 was destroyed in north of Kharkiv, the attack helicopter with registration number RF-13654 was the third visually reported loss of that type.[36] On 16 May, another Mi-28N with registration number RF-13628 was destroyed in Kharkiv.[37] On 12 June, a Mi-28H was destroyed and its wreck recorded in video by Ukrainian troops, the crew of the aircraft died at the crash site.[38]

Iraq

In October 2012, it was reported that Russia and Iraq may sign a US$4.2–$5.0 billion weapons contract, including purchase of 30 Mi-28NE helicopters.[39] The deal was confirmed on 9 October.[40] The deal was reportedly cancelled due to Iraqi concerns of corruption,[41] but that concern was addressed, and the Iraqi defence minister stated that "the deal is going ahead."[42][43] Despite early complications, all parts of the $4.2 billion contracts were signed, and are being inducted. The deliveries of 10 Mi-28NE helicopters for Iraq began in September 2013. Another batch of 13 Mi-28NE helicopters was delivered in January 2014.[44]

Iraqi Mi-28s saw their first combat deployment during the Battle of Ramadi in November 2015.[45]

Algeria

In June 2010, Algeria was expected to place an order for 42 Mi-28NE helicopters.[46] On 30 August 2016, Algeria displayed its first batch of Mi-28NE helicopters on television.[47]

Bangladesh

In late December 2021, it was reported that Bangladesh is finalizing a government-to-government (G2G) deal to buy eight Mi-28NEs for the Bangladesh Air Force with necessary equipment, along with operation and maintenance training.[48][49]

India

The Indian Military asked for a modified prototype of Mi-28 fitted with French and Belgian avionics. Russian manufacturers were discussing how to meet these requirements.[50] In late October 2011, it was reported that the American AH-64D had emerged as the front-runner ahead of the Mi-28N to fill a requirement for 22 attack helicopters.[51][52]

Kenya

In late 2011, Kenya began the process of acquiring 16 Mi-28 ground attack helicopters for its Embakasi based 50th Air Cavalry Division. The helicopters were set to be delivered to the 50th Air Cavalry Division in Kenya on 3 January 2012, from the Russian state owned corporation Rosoboronexport, which is an intermediary for all imports and exports of military related hardware.[53] However, in 2013, Oboronprom denied reports that the type had been accepted for service with the Kenyan military.[54]

Venezuela

In April 2010, Venezuela agreed to order 10 Mi-28s for the Venezuelan Army.[55] However, no deal was signed after this.

Variants

.jpg.webp)

- Mi-28

- Prototype version; first flight in 1982.

- Mi-28A

- Original production anti-tank helicopter.

- Mi-28N/MMW Havoc

- All weather day-night version adopted by Russian military in 2009. Equipped with a top-mounted millimeter wave radar, thermographic camera-TV, and a laser rangefinder. Powered by two Russian Klimov TV3-117VMA-SB3 engines (2,500 hp each), produced by the Ukrainian Motor-Sich and replaced by Russian-made VK-2500 (2,699 hp each) engines as of 2016.[56] Max takeoff weight: 11,500 kg, max payload: 2,350 kg.

- Mi-28NE

- Export version of the Mi-28N. In service with the Iraqi and Algerian Air Force.[57] In August 2018, the Russian Helicopters unveiled an upgraded Mi-28NE variant, with improvements made in the main rotor system and engine unit and new on-board radio-electronic equipment.[58] The helicopter has enhanced armor and is fitted with modern directional IR countermeasures (DIRCM) against short-range IR guided missiles. Its rotor blades made of composite materials can withstand shells up to 20–30 mm, while the fuel system is to be fire and explosion resistant.[59] It will be also capable to use the new 9M123 Khrizantema-V anti-tank guided missiles (ATGMs).[60]

- Mi-28NM

- An upgraded version of the Mi-28N under development since 2009. The helicopter has redesigned nose hull due to removal of its nose antenna, new H025 radar station for all-round visibility, more powerful VK-2500P engines with FADEC instead of the previous Klimov TV3-117VMA engines and improved rotor blades to increase its maximum speed by 13% and cruise speed by 10%. Besides that, it has an upgraded fire-control system and new "Izdeliye 296" onboard radio-electronic data processing system.[61][62] It will be equipped to carry the 9M123 Khrizantema-V and 9M127-1 Ataka-VM anti-tank missiles. It is also planned to be equipped with the new "Izdeliye 305" or LMUR multipurpose missile, designed for use against air and ground targets, and fitted with inertial guidance in initial flight, with mid-course updates by an operator before the target is acquired by the missile's own seeker, giving a range of 25 km (16 mi).[63] The Mi-28NM made its maiden flight in October 2016 and the state trials of the upgraded VK-2500P engines were completed in October 2020.[26][64] A plan to upgrade existing Mi-28Ns to Mi-28NM standard has been approved.[65][66]

- Mi-28D

- Simplified daylight operation version. Similar to Mi-28N, but without top-mounted radar and FLIR.

- Mi-40

- Proposed armed transport version. Never reached prototype stage.

- Mi-28UB

- (Uchebno-Boyevoy, training-and-combat)[67]

Mi-40

The Mil Mi-40 was a projected utility version of the Mi-28, first initiated in 1983, announced in 1992 and shown at the Moscow Airshow in 1993. It was primarily intended for the "Aerial Infantry Fighting Vehicle" category as a successor to the Mil Mi-24 and Mi-8 assault helicopters. It was planned to use two 1,863 kW Klimov TV3-117 turboshaft engines, four-blade main rotor, four-blade Delta H tail rotor (both from the Mi-28), and retractable tricycle-type landing gear. It was expected to weigh 11–12,000 kg and estimated to attain a 3300 m ceiling, a 314 km/h maximum speed and a 260 km/h cruise speed.

Specifications required the functioning in day, night and poor weather as well as carrying eight soldiers (the design achieved seven in practice), eight stretchers or large external loads. An emphasis was placed on survivability with a focus on redundancy, IR suppression and special shock absorbers for the crew to increase the maximum "safe" crash velocity. The design incorporated a 23 mm rotary cannon (most likely GSh-23L) for defense in the forward hemisphere and a 12.7 mm heavy machine gun (most likely Yak-B) for defense in the rear. Fuselage fairings containing fuel replaced stub wings with missiles mounted above on special hardpoints.

Its design borrowed much from the Mil Mi-36 developed over the previous two years, and was itself replaced after a year by the Mil Mi-42 project. Although the Mi-40 design was resurrected for a short period in the 1990s, with optimization studies being completed, it did not reach the prototype stage.

Operators

Notable accidents

.jpg.webp)

On 2 August 2015, an Mi-28 of the Berkut squadron crashed while performing in an aerobatics display with other helicopters in Ryazan. Of the crew, the pilot Lieutenant Colonel Igor Butenko died as a result of the crash while the co-pilot Senior Lieutenant Alexander Kletnov survived. While the specific cause of the crash remains undetermined, the co-pilot indicated in his report that the aircraft suffered a hydraulics failure. As a result, the Russian military grounded all Mi-28s during the investigation.[71]

Specifications (Mi-28N)

Data from RIA Novosti,[72] Russian Helicopters, JSC,[73] Jane's All The World's Aircraft 2000–2001[74]

General characteristics

- Crew: 2 (1 pilot, 1 WSO)

- Length: 17.01 m (55 ft 10 in) excluding rotors

- Wingspan: 4.88 m (16 ft 0 in) stub wings

- Height: 3.82 m (12 ft 6 in) to top of rotor head

- Empty weight: 8,590 kg (18,938 lb) equipped

- Gross weight: 10,700 kg (23,589 lb)

- Max takeoff weight: 11,500 kg (25,353 lb)

- Fuel capacity: 1,337 kg (2,948 lb) / 1,720 l (450 US gal; 380 imp gal) internal fuel + up to 445 kg (981 lb) / 571 l (151 US gal; 126 imp gal) in 4x drop tanks

- Powerplant: 2 × Klimov TV3-117 turboshaft engines, 1,636 kW (2,194 hp) each

- Main rotor diameter: 17.2 m (56 ft 5 in)

- Main rotor area: 232.35 m2 (2,501.0 sq ft)

Performance

- Maximum speed: 320 km/h (200 mph, 170 kn)

- Cruise speed: 270 km/h (170 mph, 150 kn) max

- Range: 435 km (270 mi, 235 nmi) with 5% reserve

- Combat range: 200 km (120 mi, 110 nmi) 10-minute loiter with 5% reserve

- Ferry range: 1,100 km (680 mi, 590 nmi) 4x drop tanks with 5% reserve

- Endurance: 2 hours

- Service ceiling: 5,700 m (18,700 ft)

- Hover ceiling OGE: 3,600 m (11,811 ft)

- g limits: +3 -0.5

- Rate of climb: 13.6 m/s (2,680 ft/min) max at sea level

- Disk loading: 49.5 kg/m2 (10.1 lb/sq ft) max

- Power/mass: 0.31 kW/kg (0.19 hp/lb)

Armament

- Guns: 1× chin-mounted 30 mm Shipunov 2A42 cannon with 250 rounds (±110° horizontal fire)

- Hardpoints: Two pylons under each stub wing to mount bombs, rockets, missiles, and gun pods. Main armament configurations include:

- 16 Ataka-V anti-tank missiles and 40 S-8 rockets, Or

- 16 Ataka-V anti-tank missiles, and 10 S-13 rocket, Or

- 16 Ataka-V anti-tank missiles, and two 23 mm UPK-23-250 gun pods each containing a GSh-23L with 250 rounds.

- Other ordnance: 9K121 Vikhr, and 9M123 Khrizantema anti-tank missiles, "Iz 305" LMUR AGM/ATGM, 8 Igla-V and Vympel R-73 air-to-air missiles, 2 KMGU-2 mine dispensers

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

- Agusta A129 Mangusta

- AgustaWestland Apache

- Bell AH-1Z Viper

- Boeing AH-64 Apache

- CAIC Z-10

- Denel Rooivalk

- Eurocopter Tiger

- HAL Light Combat Helicopter

- Harbin WZ-19

- IAIO Toufan

- Kamov Ka-50/Ka-52

- Panha 2091

- TAI/AgustaWestland T129

References

The initial version of this article was based on material from aviation.ru. It has been released under the GFDL by the copyright holder.

- Citations

- "Mil Mi-28". Jane's Helicopter Markets and Systems. Jane's Information Group, 2010. (Subscription article dated 30 April 2010).

- "Журнал Взлёт: ВВС России передано еще шесть Ми-28Н". Take-off.ru. 8 October 2011. Archived from the original on 6 February 2012.

- "Министарство одбране РФ увело у оперативну употребу "Ноћне ловце" Ми-28Н". Руска реч. 31 December 2013. Archived from the original on 10 January 2016. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- Frawley, Gerald. "Mil Mi-28". The International Directory of Military Aircraft, 2002/2003, p. 128. Aerospace Publications, 2002. ISBN 1-875671-55-2.

- http://www.mvzmil.ru/rus/index.php?id=145%5B%5D Russian page. Pictures of early Mi-28s can be found here.

- "First Mi-28N helicopter passes factory tests" Archived 26 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine. RIA Novosti, 30 May 2006.

- "Russian Air Force receives first Mi-28 Night Hunter helicopter" Archived 16 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine. RIA Novosti, 5 June 2006.

- "Russian military to purchase 10–15 Mi-28N helicopters per year" Archived 23 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine. RIA Novosti, 22 January 2008.

- "ЦАМТО / Новости / "Роствертол" поставит более 120 вертолетов Ми-28 и Ми-35 в 2016-2018 гг". armstrade.org. Archived from the original on 14 September 2016. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- "Russia to Develop 5th-Generation Attack Helicopter by 2017". airrecognition.com. 23 December 2013. Archived from the original on 4 April 2016. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- "KRET To Showcase Helmet-mounted Display For 'Night Hunter' Helicopters At HeliRussia-2018". www.defenseworld.net. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- "MI-28 Havoc-Russian military analysis". Warfare.be. Archived from the original on 25 October 2013. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- "Russian helicopters receive new NVG system | Jane's 360". Archived from the original on 23 March 2019. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- "Mil Mi-28". all-aero.com. Archived from the original on 10 April 2019. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- "KBP Instrument Design Bureau – 2A42". Archived from the original on 7 April 2019.

- Mlandenov Air International January 2020, p. 89

- "Rosoboronexport – Aerospace Systems Catalogue". Scribd.com. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

- "Ataka-V 9M120 (AT-16)". Fas.org. Archived from the original on 16 March 2011. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

- "Комплекс авиационного управляемого оружия Угроза (С-5кор, С-8кор, С-13кор)". rbase.new-factoria.ru. Archived from the original on 10 April 2019. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- "Ми-28Н". airwar.ru. Archived from the original on 10 April 2019. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- "ЦАМТО / Новости / Минобороны России заключило контракты на поставку вертолетов Ми-28УБ и Ми-26". armstrade.org. Archived from the original on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- "Первые два вертолета Ми-28УБ прибыли в Торжок". bmpd.livejournal.com. 19 November 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- Axe, David (30 March 2016). "Russia's Secret Weapon of the ISIS War". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on 2 April 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- "Russian Kamov Ka-52 'Alligator' Sees Combat Debut in Syria". ainonline.com. 5 April 2016. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- RT (7 April 2016). "Combat cam: Russian Mi-28NE 'Night Hunter' choppers eliminate ISIS targets". Archived from the original on 9 April 2016. Retrieved 8 April 2016 – via YouTube.

- Mlandenov Air International February 2020, p. 84

- "Russian MoD orders initial batch of Mi-28NM attack helicopters". Air Recognition. 20 December 2017. Archived from the original on 26 December 2017. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- "Вертолет Ми-28НМ в Сирии". bmpd.livejournal.com. 23 March 2019. Archived from the original on 23 March 2019. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- "Наглотаться пыли: "Ночной суперохотник" обкатают жарой и песком". iz.ru. 21 March 2019. Archived from the original on 23 March 2019. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- "ВКС России получили первые два серийных вертолета Ми-28НМ". bmpd.livejournal.com. 24 June 2019. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- "Ростех заключил контракт с Минобороны РФ на поставку 98 Ми-28НМ". russianhelicopters.aero. 27 June 2019. Archived from the original on 30 June 2019. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- "ЦАМТО / Главное / На форуме «Армия-2022» подписаны 7 и вручены 29 госконтрактов с 26 предприятиями ОПК".

- Newdick, Thomas (17 March 2022). "Russian Attack Helicopters Are Now Wildly Lobbing Rockets Over Ukraine (Updated)". The Drive. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- Parker, Charlie; Brown, Larisa (1 April 2022). "UK missile shoots down first Russian helicopter in Ukraine war". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

- "Wreckage of Russian Mi-28 helicopter found outside Kyiv". 26 April 2022.

- "Військові України збили російський ударний гелікоптер Ми-28Н «Ночной охотник»". Mil.in.ua (in Ukrainian). 10 May 2022.

- "На Харківщині ідентифікували збитий російський Ми-28H". Mil.in.ua (in Ukrainian). 16 May 2022.

- "Морпіхи ЗСУ знайшли залишки Ми-28Н та російських льотчиків". Mil.in.ua (in Ukrainian). 13 June 2022.

- "Baby Come Back: Iraq is Buying Russian Weapons Again" Archived 14 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine. defenseindustrydaily.com, 12 November 2012.

- "Iraq PM Confirms $4 Bln Arms Deal with Russia" Archived 29 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine. RIA Novosti, 9 October 2012.

- "Iraq cancels $4.2bn Russian arms deal over 'corruption'" Archived 7 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine. BBC, 10 November 2012.

- "Iraq to go ahead with billion-dollar Russian arms deal" Archived 8 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Globalpost.com, 10 November 2012.

- Venyavsky, Sergey. "Iraq Denies Cancellation of $4.2 Bln Arms Deal with Russia" Archived 3 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine. RIA Novosti, 10 November 2012.

- First Images Of The New Iraqi Mi-28 Night Hunter Attach Helicopters Archived 23 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine – The Aviationist, 27 February 2014

- "Death From Above – Iraqi Mi-28s Rain Pain on ISIS". funker530.com. 9 November 2015. Archived from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link), (English translation) Archived 14 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine - Binnie, Jeremy (31 August 2016). "Algeria shows Mi-28NE helicopters for the first time". IHS Jane's. London. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- "Bangladesh to buy Russian Mi-28NE attack helicopter, rejects U.S. AH-64 Apache". frontierindia. 30 December 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "রাশিয়া থেকে কেনা হচ্ছে ৮টি অ্যাটাক হেলিকপ্টার". Bonik Barta (in Bengali). 26 December 2021. Retrieved 26 December 2021.

- . Defense News

- Sputnik (25 October 2011). "Russia loses $600 mln Indian attack helicopter tender". rian.ru. Archived from the original on 21 July 2013. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- "US likely to bag $1.4bn deal for 22 attack choppers" Archived 30 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Times of India, 28 October 2011.

- Wabala, Dominic (9 February 2012). "KENYA BUYS RUSSIAN GUNSHIPS". The Star. Archived from the original on 19 February 2014.

- "Russia Looks To Recharge Helicopter Industry". 13 May 2016. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "Latin American Herald Tribune – Putin: Venezuela to Buy More Than $5 billion in Russian Arms". Laht.com. Archived from the original on 13 June 2012. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

- ""Ночной охотник" сменил украинские двигатели на российские – Еженедельник "Военно-промышленный курьер"". vpk-news.ru. Archived from the original on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- "Mi-28NE Night Hunter Attack Helicopter". airforce-technology.com. Archived from the original on 23 March 2019. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- "Russian Helicopters showcases modernized variant of Mi-28NE attack helicopter". armyrecognition.com. 23 August 2018. Archived from the original on 26 March 2019. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- "New Russian Gunship Implements Syrian Combat Lessons". defense-update.com. 22 August 2018. Archived from the original on 23 August 2018. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- "Army 2018: Russian Helicopters unveils upgraded Mi-28NE helicopter". 21 August 2018. Archived from the original on 23 August 2018.

- "Ми-28НМ". airwar.ru. Archived from the original on 10 April 2019. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ""Вертолеты России" приступили к госиспытаниям вертолета Ми-28НМ". TASS. 25 March 2017. Archived from the original on 10 April 2019. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- Mlandenov Air International February 2020, pp. 82–83

- "VK-2500P Engine for Russia's Mi-28NM Helicopter Passes State Trials".

- "Russia's Mi-28NM "Breakthrough" Gunship Can Launch Drones".

- "Russian MoD Approves Upgrade of Mi-28 Helicopters to the Latest Mi-28NM Standard".

- Russian Helos Announces Mil MI-28 Combat Training Variant Archived 2 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine – Aviationweek.com, 9 August 2013

- "World Air Forces 2019". Flightglobal Insight. 2019. Archived from the original on 23 January 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- The Military Balance 2020, p. 201

- "Uganda acquires Mi-28 attack helicopters". defenceWeb. 17 June 2022. Retrieved 18 June 2022.

- "Fatal helicopter crash grounds Russian helicopters". BBC World News. 2 August 2015. Archived from the original on 15 June 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- "Ми-28Н "Ночной охотник"". РИА Новости. 2011. Archived from the original on 7 March 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- "Mi-28NE "Night Hunter"". Russian Helicopters. Archived from the original on 12 January 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- Jackson, Paul, ed. (2000). Jane's all the World's Aircraft 2000–01 (91st ed.). Coulsdon, Surrey, United Kingdom: Jane's Information Group. pp. 428–429. ISBN 978-0710620118.

- Bibliography

- Eden, Paul, ed. (July 2006). The Encyclopedia of Modern Military Aircraft. London, UK: Amber Books, 2004. ISBN 978-1-904687-84-9.

- Mladenov, Alexander (January 2020). "Mean Havoc rising". Air International. Vol. 98, no. 1. pp. 82–89. ISSN 0306-5634.

- Mladenov, Alexander (February 2020). "Mean Havoc Rising: Part 2". Air International. Vol. 98, no. 2. pp. 80–85. ISSN 0306-5634.

External links

- Mi-28 page on army-technology.com

- Mi-28 page on helis.com

- Mi-28 on globalsecurity.org

- Airshow video on YouTube

- Russian Mi-28Ns to receive N025 radars in 2016 Jane's Information Group, IHS Jane's Defence Weekly, 27 August 2015, Nikolai Novichkov, Moscow.