Moa

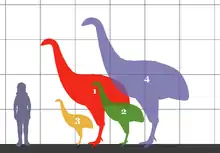

Moa[note 1] (order Dinornithiformes) are an extinct group of flightless birds formerly endemic to New Zealand.[4][note 2] There were nine species (in six genera). The two largest species, Dinornis robustus and Dinornis novaezelandiae, reached about 3.6 m (12 ft) in height with neck outstretched, and weighed about 230 kg (510 lb)[5] while the smallest, the bush moa (Anomalopteryx didiformis), was around the size of a turkey.[6] Estimates of the moa population when Polynesians settled New Zealand circa 1300 vary between 58,000[7] and approximately 2.5 million.[8]

| Moa | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| North Island giant moa skeleton | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Infraclass: | Palaeognathae |

| Clade: | Notopalaeognathae |

| Order: | †Dinornithiformes Bonaparte, 1853[1] |

| Type species | |

| †Dinornis novaezealandiae Owen, 1843 | |

| Subgroups | |

|

See text | |

| Diversity[2] | |

| 6 genera, 9 species | |

| Synonyms[3] | |

| |

Moa are traditionally placed in the ratite group.[4] However, their closest relatives have been found by genetic studies to be the flighted South American tinamous, once considered to be a sister group to ratites.[9] The nine species of moa were the only wingless birds, lacking even the vestigial wings that all other ratites have. They were the largest terrestrial animals and dominant herbivores in New Zealand's forest, shrubland, and subalpine ecosystems until the arrival of the Māori, and were hunted only by the Haast's eagle. Moa extinction occurred within 100 years of human settlement of New Zealand, primarily due to overhunting by Māori.[7]

Etymology

The word moa is a Polynesian term for domestic fowl. The name was not in common use among the Māori by the time of European contact, likely because the bird it described had been extinct for some time, and traditional stories about it were rare. The earliest record of the name was by missionaries William Williams and William Colenso in January 1838; Colenso speculated that the birds may have resembled gigantic fowl. In 1912, Māori chief Urupeni Pūhara claimed that the moa's traditional name was "te kura" (the red bird).[10]

Description

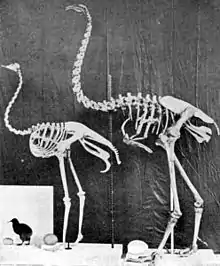

Moa skeletons were traditionally reconstructed in an upright position to create impressive height, but analysis of their vertebral articulations indicates that they probably carried their heads forward,[11] in the manner of a kiwi. The spine was attached to the rear of the head rather than the base, indicating the horizontal alignment. This would have let them graze on low vegetation, while being able to lift their heads and browse trees when necessary. This has resulted in a reconsideration of the height of larger moa. However, Māori rock art depicts moa or moa-like birds (likely geese or adzebills) with necks upright, indicating that moa were more than capable of assuming both neck postures.[12][13]

No records survive of what sounds moa made, though some idea of their calls can be gained from fossil evidence. The trachea of moa were supported by many small rings of bone known as tracheal rings. Excavation of these rings from articulated skeletons has shown that at least two moa genera (Euryapteryx and Emeus) exhibited tracheal elongation, that is, their trachea were up to 1 m (3 ft) long and formed a large loop within the body cavity.[11] They are the only ratites known to exhibit this feature, which is also present in several other bird groups, including swans, cranes, and guinea fowl. The feature is associated with deep resonant vocalisations that can travel long distances.

Evolutionary relationships

The moa's closest relatives are small terrestrial South American birds called the tinamous, which can fly.[9][14][15][16] Previously, the kiwi, the Australian emu, and cassowary[17] were thought to be most closely related to moa.

Although dozens of species were described in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many were based on partial skeletons and turned out to be synonyms. Currently, 11 species are formally recognised, although recent studies using ancient DNA recovered from bones in museum collections suggest that distinct lineages exist within some of these. One factor that has caused much confusion in moa taxonomy is the intraspecific variation of bone sizes, between glacial and interglacial periods (see Bergmann’s rule and Allen’s rule) as well as sexual dimorphism being evident in several species. Dinornis seems to have had the most pronounced sexual dimorphism, with females being up to 150% as tall and 280% as heavy as males—so much bigger that they were formerly classified as separate species until 2003.[18][19] A 2009 study showed that Euryapteryx curtus and E. gravis were synonyms.[20] A 2010 study explained size differences among them as sexual dimorphism.[21] A 2012 morphological study interpreted them as subspecies, instead.[22]

Analyses of ancient DNA have determined that a number of cryptic evolutionary lineages occurred in several moa genera.[23] These may eventually be classified as species or subspecies; Megalapteryx benhami (Archey) is synonymised with M. didinus (Owen) because the bones of both share all essential characters. Size differences can be explained by a north–south cline combined with temporal variation such that specimens were larger during the Otiran glacial period (the last ice age in New Zealand). Similar temporal size variation is known for the North Island's Pachyornis mappini.[24] Some of the other size variation for moa species can probably be explained by similar geographic and temporal factors.[25]

The earliest moa remains come from the Miocene Saint Bathans Fauna. Known from multiple eggshells and hind limb elements, these represent at least two already fairly large-sized species.[26]

Classification

Taxonomy

_601344.jpg.webp)

The currently recognised genera and species are:[5]

- Order †Dinornithiformes (Gadow 1893) Ridgway 1901 [Dinornithes Gadow 1893; Immanes Newton 1884] (moa)

- Family Dinornithidae Owen 1843 [Palapteryginae Bonaparte 1854; Palapterygidae Haast 1874; Dinornithnideae Stejneger 1884] (giant moa)

- Genus Dinornis

- North Island giant moa, Dinornis novaezealandiae (North Island, New Zealand)

- South Island giant moa, Dinornis robustus (South Island, New Zealand)

- Genus Dinornis

- Family Emeidae (Bonaparte 1854) [Emeinae Bonaparte 1854; Anomalopterygidae Oliver 1930; Anomalapteryginae Archey 1941] (lesser moa)

- Genus Anomalopteryx

- Bush moa, Anomalopteryx didiformis (North and South Island, New Zealand)

- Genus Emeus

- Eastern moa, Emeus crassus (South Island, New Zealand)

- Genus Euryapteryx

- Broad-billed moa, Euryapteryx curtus (North and South Island, New Zealand)

- Genus Pachyornis

- Heavy-footed moa, Pachyornis elephantopus (South Island, New Zealand)

- Mantell's moa, Pachyornis geranoides (North Island, New Zealand)

- Crested moa, Pachyornis australis (South Island, New Zealand)[2]

- Genus Anomalopteryx

- Family Megalapterygidae

- Genus Megalapteryx

- Upland moa, Megalapteryx didinus (South Island, New Zealand)

- Genus Megalapteryx

- Family Dinornithidae Owen 1843 [Palapteryginae Bonaparte 1854; Palapterygidae Haast 1874; Dinornithnideae Stejneger 1884] (giant moa)

Two unnamed species from the Saint Bathans Fauna.[26]

Phylogeny

Because moa are a group of flightless birds with no vestiges of wing bones, questions have been raised about how they arrived in New Zealand, and from where. Many theories exist about the moa's arrival and radiation in New Zealand, but the most recent theory suggests that they arrived in New Zealand about 60 million years ago (Mya) and split from the "basal" (see below) moa species, Megalapteryx about 5.8 Mya[27] instead of the 18.5 Mya split suggested by Baker et al. (2005). This does not necessarily mean there was no speciation between the arrival 60 Mya and the basal split 5.8 Mya, but the fossil record is lacking and most likely the early moa lineages existed, but became extinct before the basal split 5.8 Mya.[28] The presence of Miocene-aged species certainly suggests that moa diversification began before the split between Megalapteryx and the other taxa.[26]

The Oligocene Drowning Maximum event, which occurred about 22 Mya, when only 18% of present-day New Zealand was above sea level, is very important in the moa radiation. Because the basal moa split occurred so recently (5.8 Mya), it was argued that ancestors of the Quaternary moa lineages could not have been present on both the South and North Island remnants during the Oligocene drowning.[29] This does not imply that moa were previously absent from the North Island, but that only those from the South Island survived, because only the South Island was above sea level. Bunce et al. (2009) argued that moa ancestors survived on the South Island and then recolonised the North Island about 2 My later, when the two islands rejoined after 30 My of separation.[19] The presence of Miocene moa in the Saint Bathans fauna seems to suggest that these birds increased in size soon after the Oligocene Drowning Event, if they were affected by it at all.[26]

Bunce et al. also concluded that the highly complex structure of the moa lineage was caused by the formation of the Southern Alps about 6 Mya, and the habitat fragmentation on both islands resulting from Pleistocene glacial cycles, volcanism, and landscape changes.[19] The cladogram below is a phylogeny of Palaeognathae generated by Mitchell (2014)[15] with some clade names after Yuri et al. (2013).[30] It provides the position of the moa (Dinornithiformes) within the larger context of the "ancient jawed" (Palaeognathae) birds:

| Palaeognathae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The cladogram below gives a more detailed, species-level phylogeny, of the moa branch (Dinornithiformes) of the "ancient jawed" birds (Palaeognathae) shown above:[19]

| †Dinornithiformes |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Distribution and habitat

Analyses of fossil moa bone assemblages have provided detailed data on the habitat preferences of individual moa species, and revealed distinctive regional moa faunas:[11][31][32][33][34][35][36]

South Island

The two main faunas identified in the South Island include:

- The fauna of the high-rainfall west coast beech (Nothofagus) forests that included Anomalopteryx didiformis (bush moa) and Dinornis robustus (South Island giant moa), and

- The fauna of the dry rainshadow forest and shrublands east of the Southern Alps that included Pachyornis elephantopus (heavy-footed moa), Euryapteryx gravis, Emeus crassus, and Dinornis robustus.

A 'subalpine fauna' might include the widespread D. robustus, and the two other moa species that existed in the South Island:

- Pachyornis australis, the rarest moa species, the only moa species not yet found in Māori middens. Its bones have been found in caves in the northwest Nelson and Karamea districts (such as Honeycomb Hill Cave), and some sites around the Wānaka district.

- Megalapteryx didinus, more widespread, named "upland moa" because its bones are commonly found in the subalpine zone. However, it also occurred down to sea level, where suitable steep and rocky terrain (such as Punakaiki on the west coast and Central Otago) existed. Their distributions in coastal areas have been rather unclear, but were present at least in several locations such as on Kaikōura, Otago Peninsula,[37] and Karitane.[38]

North Island

Significantly less is known about North Island paleofaunas, due to a paucity of fossil sites compared to the South Island, but the basic pattern of moa-habitat relationships was the same.[11] The South Island and the North Island shared some moa species (Euryapteryx gravis, Anomalopteryx didiformis), but most were exclusive to one island, reflecting divergence over several thousand years since lower sea level in the Ice Age had made a land bridge across the Cook Strait.[11]

In the North Island, Dinornis novaezealandiae and Anomalopteryx didiformis dominated in high-rainfall forest habitat, a similar pattern to the South Island. The other moa species present in the North Island (Euryapteryx gravis, E. curtus, and Pachyornis geranoides) tended to inhabit drier forest and shrubland habitats. P. geranoides occurred throughout the North Island. The distributions of E. gravis and E. curtus were almost mutually exclusive, the former having only been found in coastal sites around the southern half of the North Island.[11]

Behaviour and ecology

About eight moa trackways, with fossilised moa footprint impressions in fluvial silts, have been found in the North Island, including Waikanae Creek (1872), Napier (1887), Manawatū River (1895), Marton (1896), Palmerston North (1911) (see photograph to left), Rangitīkei River (1939), and under water in Lake Taupō (1973). Analysis of the spacing of these tracks indicates walking speeds between 3 and 5 km/h (1.75–3 mph).[11]

Diet

Their diet has been deduced from fossilised contents of their gizzards[39][40] and coprolites,[41] as well as indirectly through morphological analysis of skull and beak, and stable isotope analysis of their bones.[11] Moa fed on a range of plant species and plant parts, including fibrous twigs and leaves taken from low trees and shrubs. The beak of Pachyornis elephantopus was analogous to a pair of secateurs, and could clip the fibrous leaves of New Zealand flax (Phormium tenax) and twigs up to at least 8 mm in diameter.[40]

Moa filled the ecological niche occupied in other countries by large browsing mammals such as antelope and llamas.[42] Some biologists contend that a number of plant species evolved to avoid moa browsing.[42] Divaracating plants such as Pennantia corymbosa (the kaikōmako), which have small leaves and a dense mesh of branches, and Pseudopanax crassifolius (the horoeka or lancewood), which has tough juvenile leaves, are possible examples of plants that evolved in such a way.

Like many other birds, moa swallowed gizzard stones (gastroliths), which were retained in their muscular gizzards, providing a grinding action that allowed them to eat coarse plant material. These stones were commonly smooth rounded quartz pebbles, but stones over 110 millimetres (4 in) long have been found among preserved moa gizzard contents.[40] Dinornis gizzards could often contain several kilograms of stones.[11] Moa likely exercised a certain selectivity in the choice of gizzard stones and chose the hardest pebbles.[43]

Reproduction

The pairs of species of moa described as Euryapteryx curtus / E. exilis, Emeus huttonii / E. crassus, and Pachyornis septentrionalis / P. mappini have long been suggested to constitute males and females, respectively. This has been confirmed by analysis for sex-specific genetic markers of DNA extracted from bone material.[18]

For example, before 2003, three species of Dinornis were recognised: South Island giant moa (D. robustus), North Island giant moa (D. novaezealandiae), and slender moa (D. struthioides). However, DNA showed that all D. struthioides were males, and all D. robustus were females. Therefore, the three species of Dinornis were reclassified as two species, one each formerly occurring on New Zealand's North Island (D. novaezealandiae) and South Island (D. robustus);[18][44] D. robustus however, comprises three distinct genetic lineages and may eventually be classified as many species, as discussed above.

Examination of growth rings in moa cortical bone has revealed that these birds were K-selected, as are many other large endemic New Zealand birds.[17] They are characterised by having a low fecundity and a long maturation period, taking about 10 years to reach adult size. The large Dinornis species took as long to reach adult size as small moa species, and as a result, had fast skeletal growth during their juvenile years.[17]

No evidence has been found to suggest that moa were colonial nesters. Moa nesting is often inferred from accumulations of eggshell fragments in caves and rock shelters, little evidence exists of the nests themselves. Excavations of rock shelters in the eastern North Island during the 1940s found moa nests, which were described as "small depressions obviously scratched out in the soft dry pumice".[45] Moa nesting material has also been recovered from rock shelters in the Central Otago region of the South Island, where the dry climate has preserved plant material used to build the nesting platform (including twigs clipped by moa bills).[46] Seeds and pollen within moa coprolites found among the nesting material provide evidence that the nesting season was late spring to summer.[46]

Fragments of moa eggshell are often found in archaeological sites and sand dunes around the New Zealand coast. Thirty-six whole moa eggs exist in museum collections and vary greatly in size (from 120–240 millimetres (4.7–9.4 in) in length and 91–178 millimetres (3.6–7.0 in) wide).[47] The outer surface of moa eggshell is characterised by small, slit-shaped pores. The eggs of most moa species were white, although those of the upland moa (Megalapteryx didinus) were blue-green.[48]

A 2010 study by Huynen et al. found that the eggs of certain species were fragile, only around a millimetre in shell thickness: "Unexpectedly, several thin-shelled eggs were also shown to belong to the heaviest moa of the genera Dinornis, Euryapteryx, and Emeus, making these, to our knowledge, the most fragile of all avian eggs measured to date. Moreover, sex-specific DNA recovered from the outer surfaces of eggshells belonging to species of Dinornis and Euryapteryx suggest that these very thin eggs were likely to have been incubated by the lighter males. The thin nature of the eggshells of these larger species of moa, even if incubated by the male, suggests that egg breakage in these species would have been common if the typical contact method of avian egg incubation was used."[48] Despite the bird's extinction, the high yield of DNA available from recovered fossilised eggs has allowed the moa's genome to be sequenced.[49]

The skeleton of female upland moa with egg in unlaid position within the pelvic cavity in Otago Museum

The skeleton of female upland moa with egg in unlaid position within the pelvic cavity in Otago Museum An egg and embryo fragments of Emeus crassus

An egg and embryo fragments of Emeus crassus Restoration of an upland moa

Restoration of an upland moa

Pre-human forests

Studies of accumulated dried vegetation in the pre-human mid-late Holocene period suggests a low Sophora microphylla or Kōwai forest ecosystem in Central Otago that was used and perhaps maintained by moa, for both nesting material and food. Neither the forests nor moa existed when European settlers came to the area in the 1850s.[50]

Relationship with humans

Extinction

Before the arrival of human settlers, the moa's only predator was the massive Haast's eagle. New Zealand had been isolated for 80 million years and had few predators before human arrival, meaning that not only were its ecosystems extremely vulnerable to perturbation by outside species, but also the native species were ill-equipped to cope with human predators.[51][52]

Polynesians arrived sometime before 1300, and all moa genera were soon driven to extinction by hunting and, to a lesser extent, by habitat reduction due to forest clearance. By 1445, all moa had become extinct, along with Haast's eagle, which had relied on them for food. Recent research using carbon-14 dating of middens strongly suggests that the events leading to extinction took less than a hundred years,[53] rather than a period of exploitation lasting several hundred years as previously hypothesised.

Some authors have speculated that a few Megalapteryx didinus may have persisted in remote corners of New Zealand until the 18th and even 19th centuries, but this view is not widely accepted.[54] Some Māori hunters claimed to be in pursuit of the moa as late as the 1770s; however, these accounts possibly did not refer to the hunting of actual birds as much as a now-lost ritual among South Islanders.[55] Whalers and sealers recalled seeing monstrous birds along the coast of the South Island, and in the 1820s, a man named George Pauley made an unverified claim of seeing a moa in the Otago region of New Zealand.[56][57]

An expedition in the 1850s under Lieutenant A. Impey reported two emu-like birds on a hillside in the South Island; an 1861 story from the Nelson Examiner told of three-toed footprints measuring 36 cm (14 in) between Tākaka and Riwaka that were found by a surveying party; and finally in 1878, the Otago Witness published an additional account from a farmer and his shepherd.[57] An 80-year-old woman, Alice McKenzie, claimed in 1959 that she had seen a moa in Fiordland bush in 1887, and again on a Fiordland beach when she was 17 years old. She claimed that her brother had also seen a moa on another occasion.[58]

Surviving remains

Joel Polack, a trader who lived on the East Coast of the North Island from 1834 to 1837, recorded in 1838 that he had been shown "several large fossil ossifications" found near Mt Hikurangi. He was certain that these were the bones of a species of emu or ostrich, noting that "the Natives add that in times long past they received the traditions that very large birds had existed, but the scarcity of animal food, as well as the easy method of entrapping them, has caused their extermination". Polack further noted that he had received reports from Māori that a "species of Struthio" still existed in remote parts of the South Island.[59][60]

Dieffenbach[61] also refers to a fossil from the area near Mt Hikurangi, and surmises that it belongs to "a bird, now extinct, called Moa (or Movie) by the natives". 'Movie' is the first transcribed name for the bird.[62][63] In 1839, John W. Harris, a Poverty Bay flax trader who was a natural-history enthusiast, was given a piece of unusual bone by a Māori who had found it in a river bank. He showed the 15 cm (6 in) fragment of bone to his uncle, John Rule, a Sydney surgeon, who sent it to Richard Owen, who at that time was working at the Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons in London.[57]

Owen puzzled over the fragment for almost four years. He established it was part of the femur of a big animal, but it was uncharacteristically light and honeycombed. Owen announced to a skeptical scientific community and the world that it was from a giant extinct bird like an ostrich, and named it Dinornis. His deduction was ridiculed in some quarters, but was proved correct with the subsequent discoveries of considerable quantities of moa bones throughout the country, sufficient to reconstruct skeletons of the birds.[57]

In July 2004, the Natural History Museum in London placed on display the moa bone fragment Owen had first examined, to celebrate 200 years since his birth, and in memory of Owen as founder of the museum.

Since the discovery of the first moa bones in the late 1830s, thousands more have been found. They occur in a range of late Quaternary and Holocene sedimentary deposits, but are most common in three main types of site: caves, dunes, and swamps.

Bones are commonly found in caves or tomo (the Māori word for doline or sinkhole, often used to refer to pitfalls or vertical cave shafts). The two main ways that the moa bones were deposited in such sites were birds that entered the cave to nest or escape bad weather, and subsequently died in the cave and birds that fell into a vertical shaft and were unable to escape. Moa bones (and the bones of other extinct birds) have been found in caves throughout New Zealand, especially in the limestone/marble areas of northwest Nelson, Karamea, Waitomo, and Te Anau.

Moa bones and eggshell fragments sometimes occur in active coastal sand dunes, where they may erode from paleosols and concentrate in 'blowouts' between dune ridges. Many such moa bones antedate human settlement, although some originate from Māori midden sites, which frequently occur in dunes near harbours and river mouths (for example the large moa hunter sites at Shag River, Otago, and Wairau Bar, Marlborough).

Densely intermingled moa bones have been encountered in swamps throughout New Zealand. The most well-known example is at Pyramid Valley in north Canterbury,[64] where bones from at least 183 individual moa have been excavated, mostly by Roger Duff of Canterbury Museum.[65] Many explanations have been proposed to account for how these deposits formed, ranging from poisonous spring waters to floods and wildfires. However, the currently accepted explanation is that the bones accumulated slowly over thousands of years, from birds that entered the swamps to feed and became trapped in the soft sediment.[66]

Many New Zealand and international museums hold moa bone collections. Auckland War Memorial Museum – Tāmaki Paenga Hira has a significant collection, and in 2018 several moa skeletons were imaged and 3D scanned to make the collections more accessible.[67]

Feathers and soft tissues

Several remarkable examples of moa remains have been found which exhibit soft tissues (muscle, skin, feathers), that were preserved through desiccation when the bird died in a naturally dry site (for example, a cave with a constant dry breeze blowing through it). Most of these specimens have been found in the semiarid Central Otago region, the driest part of New Zealand. These include:

- Dried muscle on bones of a female Dinornis robustus found at Tiger Hill in the Manuherikia River Valley by gold miners in 1864[68] (currently held by Yorkshire Museum)

- Several bones of Emeus crassus with muscle attached, and a row of neck vertebrae with muscle, skin, and feathers collected from Earnscleugh Cave near the town of Alexandra in 1870[69] (currently held by Otago Museum)

- An articulated foot of a male D. giganteus with skin and foot pads preserved, found in a crevice on the Knobby Range in 1874[70] (currently held by Otago Museum)

- The type specimen of Megalapteryx didinus found near Queenstown in 1878[68] (currently held by Natural History Museum, London; see photograph of foot on this page)

- The lower leg of Pachyornis elephantopus, with skin and muscle, from the Hector Range in 1884;[54][70] (currently held by the Zoology Department, Cambridge University)

- The complete feathered leg of a M. didinus from Old Man Range in 1894[71] (currently held by Otago Museum)

- The head of a M. didinus found near Cromwell sometime before 1949[72] (currently held by the Museum of New Zealand).

Two specimens are known from outside the Central Otago region:

- A complete foot of M. didinus found in a cave on Mount Owen near Nelson in the 1980s[73] (currently held by the Museum of New Zealand)

- A skeleton of Anomalopteryx didiformis with muscle, skin, and feather bases collected from a cave near Te Anau in 1980.[74]

In addition to these specimens, loose moa feathers have been collected from caves and rock shelters in the southern South Island, and based on these remains, some idea of the moa plumage has been achieved. The preserved leg of M. didinus from the Old Man Range reveals that this species was feathered right down to the foot. This is likely to have been an adaptation to living in high-altitude, snowy environments, and is also seen in the Darwin’s rhea, which lives in a similar seasonally snowy habitat.[11]

Moa feathers are up to 23 cm (9 in) long, and a range of colours has been reported, including reddish-brown, white, yellowish, and purplish.[11] Dark feathers with white or creamy tips have also been found, and indicate that some moa species may have had plumage with a speckled appearance.[75]

Claims of survival

Occasional speculation – since at least the late 19th century,[76][77] and as recently as 1993[78][79][80] and 2008[81] – has occurred that some moa may still exist, particularly in the wilderness of South Westland and Fiordland. The 1993 report initially interested the Department of Conservation, but the animal in a blurry photograph was identified as a red deer.[82][83] Cryptozoologists continue to search for them, but their claims and supporting evidence (such as of purported footprints)[81] have earned little attention from experts and are pseudoscientific.[54] In 1880 Alice Mackenzie had a meeting with a large bird that she believed to be a takahē but when it was rediscovered in the 1940s, and Mackenzie saw what it looked like she knew she had seen something else.[84]

The rediscovery of the takahē in 1948 after none had been seen since 1898 showed that rare birds can exist undiscovered for a long time. However, the takahē is a much smaller bird than the moa, and was rediscovered after its tracks were identified—yet no reliable evidence of moa tracks has ever been found, and experts still contend that moa survival is extremely unlikely, since they would have to be living unnoticed for over 500 years in a region visited often by hunters and hikers.[81]

Potential revival

The creature has frequently been mentioned as a potential candidate for revival by cloning. Its iconic status, coupled with the facts that it only became extinct a few hundred years ago and that substantial quantities of moa remains exist, mean that it is often listed alongside such creatures as the dodo as leading candidates for de-extinction.[85] Preliminary work involving the extraction of DNA has been undertaken by Japanese geneticist Ankoh Yasuyuki Shirota.[86][87]

Interest in the moa's potential for revival was further stirred in mid-2014 when New Zealand Member of Parliament Trevor Mallard suggested that bringing back some smaller species of moa within 50 years was a viable idea.[88] The idea was ridiculed by many, but gained support from some natural history experts.[89]

In literature and culture

Heinrich Harder portrayed moa being hunted by Māori in the classic German collecting cards about extinct and prehistoric animals, "Tiere der Urwelt", in the early 1900s.

Allen Curnow's poem, "The Skeleton of the Great Moa in the Canterbury Museum, Christchurch" was published in 1943.[90][91]

See also

- List of New Zealand species extinct in the Holocene

- Moa-nalo, several flightless ducks from the Hawaiian Islands that grew to be as large as geese.

- Elephant birds, flightless ratites up to over 3 metres tall that once lived on the island of Madagascar.

General:

- Late Quaternary prehistoric birds

- Island gigantism

- Megafauna

Footnotes

- Brands, S. (2008)

- Stephenson, Brent (2009)

- Brodkob, Pierce (1963). "Catalogue of fossil birds 1. Archaeopterygiformes through Ardeiformes". Biological Sciences, Bulletin of the Florida State Museum. 7 (4): 180–293. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- OSNZ (2009)

- Davies, S.J.J.F. (2003)

- "Little bush moa | New Zealand Birds Online". nzbirdsonline.org.nz. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- Perry, George L.W.; Wheeler, Andrew B.; Wood, Jamie R.; Wilmshurst, Janet M. (1 December 2014). "A high-precision chronology for the rapid extinction of New Zealand moa (Aves, Dinornithiformes)". Quaternary Science Reviews. 105: 126–135. Bibcode:2014QSRv..105..126P. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2014.09.025. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- Latham, A. David M.; Latham, M. Cecilia; Wilmshurst, Janet M.; Forsyth, David M.; Gormley, Andrew M.; Pech, Roger P.; Perry, George L. W.; Wood, Jamie R. (March 2020). "A refined model of body mass and population density in flightless birds reconciles extreme bimodal population estimates for extinct moa". Ecography. 43 (3): 353–364. doi:10.1111/ecog.04917. ISSN 0906-7590.

- Phillips, et al. (2010)

- "Story: Moa". govt.nz. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- Worthy & Holdaway (2002)

- "Cave drawing of a moa". Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Te Ara.

- "Te Manunui Rock Art Site". Heritage New Zealand.

- Allentoft, M.E.; Rawlence, N.J. (20 January 2012). "Moa's Ark or volant ghosts of Gondwana? Insights from nineteen years of ancient DNA research on the extinct moa (Aves: Dinornithiformes) of New Zealand" (PDF). Annals of Anatomy - Anatomischer Anzeiger. 194 (1): 36–51. doi:10.1016/j.aanat.2011.04.002. PMID 21596537.

- Mitchell, K.J.; Llamas, B.; Soubrier, J.; Rawlence, N.J.; Worthy, Trevor; Wood, J.; Lee, M.S.Y.; Cooper, A. (23 May 2014). "Ancient DNA reveals elephant birds and kiwi are sister taxa and clarifies ratite bird evolution" (PDF). Science. 344 (6186): 898–900. Bibcode:2014Sci...344..898M. doi:10.1126/science.1251981. hdl:2328/35953. PMID 24855267. S2CID 206555952. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 May 2019.

- Baker, A.J.; Haddrath, O.; McPherson, J.D.; Cloutier, A. (2014). "Genomic Support for a Moa-Tinamou Clade and Adaptive Morphological Convergence in Flightless Ratites". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 31 (7): 1686–1696. doi:10.1093/molbev/msu153. PMID 24825849.

- Turvey et al. (2005)

- Huynen, L.J., et al. (2003)

- Bunce, M., et al. (2003)

- Bunce, M.; Worthy, Trevor; Phillips, M.J.; Holdaway, Richard; Willerslev, E.; Haile, J.; Shapiro, B.; Scofield, R.P.; Drummond, A.; Kamp, P.J.J.; Cooper, A. (2009). "The evolutionary history of the extinct ratite moa and New Zealand Neogene paleogeography". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (49): 20646–20651. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10620646B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0906660106. PMC 2791642. PMID 19923428.

- Gill, B.J. (2010). "Regional comparisons of the thickness of moa eggshell fragments (Aves: Dinornithiformes). In Proceedings of the VII International Meeting of the Society of Avian Paleontology and Evolution, ed. W.E. Boles and Trevor Worthy" (PDF). Records of the Australian Museum. 62: 115–122. doi:10.3853/j.0067-1975.62.2010.1535. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 April 2019.

- Worthy, Trevor; Scofield, R.P. (2012). "Twenty-first century advances in knowledge of the biology of moa (Aves: Dinornithiformes): A new morphological analysis and moa diagnoses revised". New Zealand Journal of Zoology. 39 (2): 87–153. doi:10.1080/03014223.2012.665060. S2CID 83768608.

- Baker, A.J.; Huynen, L.J.; Haddrath, O.; Millar, C.D.; Lambert, D.M. (2005). "Reconstructing the tempo and mode of evolution in an extinct clade of birds with ancient DNA: The giant moas of New Zealand". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 102 (23): 8257–8262. Bibcode:2005PNAS..102.8257B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0409435102. PMC 1149408. PMID 15928096.

- Worthy (1987)

- Worthy, et al. (1988)

- Tennyson, A.J.D.; Worthy, Trevor; Jones, C.M.; Scofield, R.P.; Hand, S.J. (2010). "Moa's Ark: Miocene fossils reveal the great antiquity of moa (Aves: Dinornithiformes) in Zealandia" (PDF). Records of the Australian Museum. 62: 105–114. doi:10.3853/j.0067-1975.62.2010.1546. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 April 2019.

- Bunce, M.; Worthy, Trevor; Phillips, M.J.; Holdaway, Richard; Willerslev, E.; Hailef, J.; Shapiro, B.; Scofield, R.P.; Drummond, A.; Kampk, P.J.J.; Cooper, A. (2009). "The evolutionary history of the extinct ratite moa and New Zealand Neogene paleogeography". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (49): 20646–20651. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10620646B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0906660106. PMC 2791642. PMID 19923428.

- Allentoft, Morten; Rawlence, Nicolas (2012). "Moa's ark or volant ghosts of Gondwana? Insights from nineteen years of ancient DNA research on the extinct moa (Aves: Dinornithiformes) of New Zealand" (PDF). Annals of Anatomy. 194 (1): 36–51. doi:10.1016/j.aanat.2011.04.002. PMID 21596537.

- Allentoft, Morten; Nicloas Rawlence (2012). "Moa's ark or volant ghosts of Gondwana? Insights from nineteen years of ancient DNA research on the extinct moa (Aves: Dinornithiformes) of New Zealand". Annals of Anatomy. 194 (1): 36–51. doi:10.1016/j.aanat.2011.04.002. PMID 21596537.

- Yuri, T. (2013). "Parsimony and model-based analyses of indels in avian nuclear genes reveal congruent and incongruent phylogenetic signals". Biology. 2 (1): 419–444. doi:10.3390/biology2010419. PMC 4009869. PMID 24832669.

- Worthy, Trevor (1998)a

- Worthy, Trevor (1998)b

- Worthy, Trevor & Holdaway, Richard (1993)

- Worthy, Trevor & Holdaway, Richard (1994)

- Worthy, Trevor & Holdaway, Richard (1995)

- Worthy, Trevor & Holdaway, Richard (1996)

- Buick L.T. (1937). "The Moa-Hunters of New Zealand: Sportsman of the Stone Age – Chapter I. Did The Maori Know The Moa?". Victoria University of Wellington Catalogue – New Zealand Texts Collection. W & T Avery Ltd. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- Teviotdale D. (1932). "The material culture of the Moa-hunters in Murihiku – 2. Evidence of Zoology". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 41 (162): 81–120. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- Burrows, et al. (1981)

- Wood (2007)

- Horrocks, et al. (2004)

- Gibbs, George W. (2006). Ghosts of Gondwana: the history of life in New Zealand. Nelson, N.Z.: Craig Potton Pub. ISBN 978-1877333484. OCLC 83611783.

- Smalley, I.J. (1979). "Moas as rockhounds". Nature. 281 (5727): 103–104. Bibcode:1979Natur.281..103S. doi:10.1038/281103b0. S2CID 33405428.

- Bunce, M.; Worthy, Trevor; Ford, T.; Hoppitt, W.; Willerslev, E.; Drummond, A.; Cooper, A. (2003). "Extreme reversed sexual size dimorphism in the extinct New Zealand moa Dinornis" (PDF). Nature. 425 (6954): 172–175. Bibcode:2003Natur.425..172B. doi:10.1038/nature01871. PMID 12968178. S2CID 1515413. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 January 2019.

- Hartree (1999)

- Wood, J.R. (2008)

- Gill, B.J. (2007)

- Huynen, Leon; Gill, Brian J.; Millar, Craig D.; and Lambert, David M. (2010)

- Yong, Ed. (2010)

- Pole, Mike (31 December 2021). "A vanished ecosystem: Sophora microphylla (Kōwhai) dominated forest recorded in mid-late Holocene rock shelters in Central Otago, New Zealand". Palaeontologia Electronica. 25 (1): 1–41. doi:10.26879/1169. ISSN 1094-8074. S2CID 245807815.

- Mein Smith, Philippa (2012). A Concise History of New Zealand. Cambridge University Press. pp. 2, 5–6. ISBN 978-1107402171.

- Milberg, Per; Tyrberg, Tommy (1993). "Naïve birds and noble savages – a review of man-caused prehistoric extinctions of island birds". Ecography. 16 (3): 229–250. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0587.1993.tb00213.x.

- Holdaway & Jacomb (2000)

- Anderson (1989)

- Anderson, Atholl (1990). Prodigious Birds: Moas and Moa-Hunting in New Zealand. Cambridge University Press.

- Purcell, Rosamond (1999)

- Fuller, Errol (1987)

- "Alice McKenzie and the Moa". Radio New Zealand.

- Polack, J.S. (1838)

- Hill, H. (1913)

- Dieffenbach, E. (1843)

- Taonga, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu. "4. – Moa – Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand". teara.govt.nz. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- Berentson, Quinn. (2012). Moa : the life and death of New Zealand's legendary bird. Nelson, N.Z.: Craig Potton. ISBN 978-1877517846. OCLC 819110163.

- Holdaway, Richard & Worthy, Trevor (1997)

- Davidson, Janet. "Roger Shepherd Duff". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage.

- Wood, J.R., et al. (2008)

- "Digitising moa". Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- Owen, R. (1879)

- Hutton, F.W. & Coughtrey, M. (1875)

- Buller, W.L. (1888)

- Hamilton, A. (1894)

- Vickers-Rich, et al. (1995)

- Worthy, Trevor (1989)

- Forrest, R.M. (1987)

- Rawlence, N.J.; Wood, J.R.; Armstrong, K.N.; Cooper, A. (2009). "DNA content and distribution in ancient feathers and potential to reconstruct the plumage of extinct avian taxa". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 276 (1672): 3395–3402. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0755. PMC 2817183. PMID 19570784.

- Gould, C. (1886)

- Heuvelmans, B (1959)

- "Animal X Classic". Animal X TV. August 2003. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 14 February 2011.

- Worthy, Trevor (2009)

- Dutton, Dennis (1994)

- Laing, Doug (2008)

- Nickell, Joe (26 May 2017). "The New Zealand Moa: From Extinct Bird to Cryptid". Skeptical Briefs. Center for Inquiry. 27 (1): 8–9.

- Nickell, Joe (26 May 2017). "The New Zealand Moa: From Extinct Bird to Cryptid". Skeptical Inquirer. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- "Alice Mackenzie describes seeing a moa and talks about her book, Pioneers of Martins Bay".

- Le Roux, M., "Scientists plan to resurrect a range of extinct animals using DNA and cloning", Courier Mail, 23 April 2013. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- Young, E (1997). "Moa genes could rise from the dead". New Scientist. 153 (2063).

- "Life in the Old Moa Yet", New Zealand Science Monthly, February 1997. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- O'Brien, T. Mallard: Bring the moa back to life within 50 years", 3news, 1 July 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- Tohill, M.-J., "Expert supports Moa revival idea", stuff.co.nz, 9 July 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- "A poem a day: The Skeleton of the Great Moa in the Canterbury Museum, Christchurch – Allen Curnow". 25 April 2011.

- Curnow, Allen (1944). Sailing or Drowning. Wellington: Progressive Publishing Society.

Notes

- The word moa is from the Māori language, and is both singular and plural. Usage in New Zealand English and in the scientific literature in recent years has been changing to reflect this.

- At least two distinct forms are also known from the Saint Bathans Fauna.

References

- Anderson, Atholl (1989). "On evidence for the survival of moa in European Fiordland" (PDF). New Zealand Journal of Ecology. 12 (Supplement): 39–44.

- Baker, Allan J.; Huynen, Leon J.; Haddrath, Oliver; Millar, Craig D.; Lambert, David M. (2005). "Reconstructing the tempo and mode of evolution in an extinct clade of birds with ancient DNA: The giant moas of New Zealand". PNAS. 102 (23): 8257–8262. Bibcode:2005PNAS..102.8257B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0409435102. PMC 1149408. PMID 15928096.

- Brands, Sheila (14 August 2008). "Systema Naturae 2000 / Classification, Order Dinornithiformes". Project: The Taxonomicon. Archived from the original on 7 March 2009. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- Buller, W.L. (1888). A history of the birds of New Zealand. London: Buller.

- Bunce, Michael; Worthy, Trevor; Ford, Tom; Hoppitt, Will; Willerslev, Eske; Drummond, Alexei; Cooper, Alan (2003). "Extreme reversed sexual size dimorphism in the extinct New Zealand moa Dinornis" (PDF). Nature. 425 (6954): 172–175. Bibcode:2003Natur.425..172B. doi:10.1038/nature01871. PMID 12968178. S2CID 1515413. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 January 2019.

- Burrows, C.; et al. (1981). "The diet of moas based on gizzard contents samples from Pyramid Valley, North Canterbury, and Scaifes Lagoon, Lake Wanaka, Otago". Records of the Canterbury Museum. 9: 309–336.

- Davies, S.J.J.F. (2003). "Moas". In Hutchins, Michael (ed.). Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. Vol. 8 Birds I Tinamous and Ratites to Hoatzins (2 ed.). Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group. pp. 95–98. ISBN 978-0-7876-5784-0.

- Dawkins, Richard (2004). A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of Life, The Ancestor's Tale. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-618-00583-3.

- Dieffenbach, E. (1843). Travels in New Zealand. Vol. II. London: John Murray. p. 195. ISBN 978-1-113-50843-0.

- Dutton, Dennis (1994). "Skeptics Meet Moa Spotters". New Zealand Skeptics Online. New Zealand: New Zealand Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2011.

- Forrest, R.M. (1987). "A partially mummified skeleton of Anomalopteryx didiformis from Southland". Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 17 (4): 399–408. doi:10.1080/03036758.1987.10426481.

- Fuller, Errol (1987). Bunney, Sarah (ed.). Extinct Birds. London, England: The Rainbird Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8160-1833-8.

- Gill, B.J. (2007). "Eggshell characteristics of moa eggs (Aves: Dinornithiformes)". Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 37 (4): 139–150. doi:10.1080/03014220709510542. S2CID 85006853.

- Gould, Charles (1886). Mythical Monsters. W.H. Allen & Co.

- Hamilton, A. (1894). "On the feathers of a small species of moa (Megalapteryx didinus) found in a cave at the head of the Waikaia River, with a notice of a moa-hunters camping place on the Old Man Range". Transactions and Proceedings of the New Zealand Institute. 27: 232–238.

- Hartree, W.H. (1999). "A preliminary report on the nesting habits of moas in the East Coast of the North Island" (PDF). Notornis. 46 (4): 457–460.

- Heuvelmans, Bernard (1959). On the Track of Unknown Animal. New York: Hill & Wang.

- Hill, H. (1913). "The Moa – Legendary, Historical and Geographical: Why and When the Moa disappeared". Transactions and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 46: 330.

- Holdaway, Richard; Jacomb, C. (2000). "Rapid Extinction of the Moas (Aves: Dinornithiformes): Model, Test, and Implications". Science. 287 (5461): 2250–2254. Bibcode:2000Sci...287.2250H. doi:10.1126/science.287.5461.2250. PMID 10731144.

- Holdaway, Richard; Worthy, Trevor (1997). "A reappraisal of the late Quaternary fossil vertebrates of Pyramid Valley Swamp, North Canterbury". New Zealand Journal of Zoology. 24: 69–121. doi:10.1080/03014223.1997.9518107.

- Horrocks, M.; et al. (2004). "Plant remains in coprolites: diet of a subalpine moa (Dinornithiformes) from southern New Zealand". Emu. 104 (2): 149–156. doi:10.1071/MU03019. S2CID 86345660.

- Hutton, F.W.; Coughtrey, M. (1874). "Notice of the Earnscleugh Cave". Transactions and Proceedings of the New Zealand Institute. 7: 138–144.

- Huynen, Leon; Gill, Brian J.; Millar, Craig D.; Lambert, David M. (30 August 2010). "Ancient DNA Reveals Extreme Egg Morphology and Nesting Behavior in New Zealand's Extinct Moa". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (30): 16201–16206. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10716201H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0914096107. PMC 2941315. PMID 20805485.

- Huynen, Leon J.; Millar, Craig D.; Scofield, R.P.; Lambert, David M. (2003). "Nuclear DNA sequences detect species limits in ancient moa". Nature. 425 (6954): 175–178. Bibcode:2003Natur.425..175H. doi:10.1038/nature01838. PMID 12968179. S2CID 4413995.

- Laing, Doug (5 January 2008). "Birdman says moa surviving in the Bay". Hawkes Bay Today. APN News & Media Ltd. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 14 February 2011.

- Millener, P.R. (1982). "And then there were twelve: the taxonomic status of Anomalopteryx oweni (Aves: Dinornithidae)" (PDF). Notornis. 29 (1): 165–170.

- OSNZ (January 2009). "New Zealand Recognised Bird Names (NZRBN) database". Ornithological Society of New Zealand Inc. Archived from the original on 25 April 2015. Retrieved 14 February 2011.

- Owen, Richard (1879). Memoirs on the Extinct Wingless Birds of New Zealand, with an Appendix of Those of England, Australia, Newfoundland, Mauritius and Rodriguez. London: John van Voorst. hdl:2152/16251.

- Phillips, Matthew J.; Gibb, Gillian C.; Crimp, Elizabeth A.; Penny, David (2010). "Tinamous and Moa Flock Together: Mitochondrial Genome Sequence Analysis Reveals Independent Losses of Flight among Ratites". Systematic Biology. 59 (1): 90–107. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syp079. PMID 20525622.

- Polack, J.S. (1838). New Zealand: Being a Narrative of Travels and Adventures During a Residence in that Country Between the Years 1831 and 1837. Vol. I. London: Richard Bentley. pp. 303, 307.

- Purcell, Rosamond (1999). Swift as a Shadow. Mariner Books. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-395-89228-2.

- Stephenson, Brent (5 January 2009). "New Zealand Recognised Bird Names (NZRBN) database". New Zealand: Ornithological Society of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 25 April 2015. Retrieved 10 May 2010.

- Turvey, Samuel T.; Green, Owen R.; Holdaway, Richard (2005). "Cortical growth marks reveal extended juvenile development in New Zealand moa". Nature. 435 (7044): 940–943. Bibcode:2005Natur.435..940T. doi:10.1038/nature03635. PMID 15959513. S2CID 4308841.

- Vickers-Rich, P; Trusler, P; Rowley, MJ; Cooper, A; Chambers, GK; Bock, WJ; Millener, PR; Worthy, Trevor; Yaldwyn, JC (1995). "Morphology, myology, collagen and DNA of a mummified moa, Megalapteryx didinus (Aves: Dinornithiformes) from New Zealand" (PDF). Tuhinga: Records of the Museum of New Zealand te Papa Tongarewa. 4: 1–26. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 May 2010.

- Wood, J.R. (2007). "Moa gizzard content analyses: further information on the diet of Dinornis robustus and Emeus crassus, and the first evidence for the diet of Pachyornis elephantopus (Aves: Dinornithiformes)". Records of the Canterbury Museum. 21: 27–39.

- Wood, J.R. (2008). "Moa (Aves: Dinornithiformes) nesting material from rockshelters in the semi-arid interior of South Island, New Zealand". Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 38 (3): 115–129. doi:10.1080/03014220809510550. S2CID 129645654.

- Wood, J.R.; Worthy, Trevor; Rawlence, N.J.; Jones, S.M.; Read, S.E. (2008). "A deposition mechanism for Holocene miring bone deposits, South Island, New Zealand". Journal of Taphonomy. 6: 1–20. hdl:2440/62495.

- Worthy, Trevor (1989). "Mummified moa remains from Mt. Owen, northwest Nelson" (PDF). Notornis. 36: 36–38.

- Worthy, Trevor (1998a). "Quaternary fossil faunas of Otago, South Island, New Zealand". Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 28 (3): 421–521. doi:10.1080/03014223.1998.9517573.

- Worthy, Trevor (1998b). "The Quaternary fossil avifauna of Southland, South Island, New Zealand". Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 28 (4): 537–589. doi:10.1080/03014223.1998.9517575.

- Worthy, Trevor; Holdaway, Richard (1993). "Quaternary fossil faunas from caves in the Punakaiki area, West Coast, South Island, New Zealand". Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 23 (3): 147–254. doi:10.1080/03036758.1993.10721222.

- Worthy, Trevor; Holdaway, Richard (1994). "Quaternary fossil faunas from caves in Takaka Valley and on Takaka Hill, northwest Nelson, South Island, New Zealand". Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 24 (3): 297–391. doi:10.1080/03014223.1994.9517474.

- Worthy, Trevor; Holdaway, Richard (1995). "Quaternary fossil faunas from caves on Mt. Cookson, North Canterbury, South Island, New Zealand". Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 25 (3): 333–370. doi:10.1080/03014223.1995.9517494.

- Worthy, Trevor; Holdaway, Richard (1996). "Quaternary fossil faunas, overlapping taphonomies, and paleofaunal reconstructions in North Canterbury, South Island, New Zealand". Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 26 (3): 275–361. doi:10.1080/03014223.1996.9517514.

- Worthy, Trevor; Holdaway, Richard (2002). The Lost World of the Moa. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34034-4.

- Worthy, Trevor (March 2009). "A moa sighting?". Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 14 February 2011.

- Yong, Ed (March 2010). "DNA from the Largest Bird Ever Sequenced from Fossil Eggshells". Discover Magazine. Retrieved 14 February 2011.

External links

- TerraNature list of New Zealand's extinct birds

- TerraNature page on Moa

- Tree of Life classification and references

- Moa article in Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

- 3D model of a moa skull

_white_background.jpg.webp)