Estonian language

Estonian (eesti keel [ˈeːsti ˈkeːl] (![]() listen)) is a Finnic language, written in the Latin script. It is the official language of Estonia and one of the official languages of the European Union, spoken natively by about 1.1 million people; 922,000 people in Estonia and 160,000 outside Estonia.[2][3]

listen)) is a Finnic language, written in the Latin script. It is the official language of Estonia and one of the official languages of the European Union, spoken natively by about 1.1 million people; 922,000 people in Estonia and 160,000 outside Estonia.[2][3]

| Estonian | |

|---|---|

| eesti keel | |

| Native to | Estonia |

| Ethnicity | Estonians |

Native speakers | 1.1 million (2013)[1] |

Uralic

| |

| Latin (Estonian alphabet) Estonian Braille | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by | Institute of the Estonian Language / Eesti Keele Instituut, Emakeele Selts (semi-official) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | et |

| ISO 639-2 | est |

| ISO 639-3 | est – inclusive codeIndividual codes: ekk – Standard Estonianvro – Võro |

| Glottolog | esto1258 |

| Linguasphere | 41-AAA-d |

Historical spread:

North Estonian (incl. Northeastern coastal Estonian)

South Estonian

By today, the language islands outside Estonia have disappeared, and considerable amount of speakers in the South Estonian area have switched to standard Estonian (based on North Estonian). | |

Classification

Estonian belongs to the Finnic branch of the Uralic language family. The Finnic languages also include Finnish and a few minority languages spoken around the Baltic Sea and in northwestern Russia. Estonian is subclassified as a Southern Finnic language and it is the second-most-spoken language among all the Finnic languages. Alongside Finnish, Hungarian and Maltese, Estonian is one of the four official languages of the European Union that are not of an Indo-European origin.

Although the Estonian and Germanic languages are of very different origins, one can identify many similar words in Estonian and German. This is primarily because the Estonian language has borrowed nearly one third of its vocabulary from Germanic languages, mainly from Low Saxon (Middle Low German) during the period of German rule, and High German (including Standard German). The percentage of Low Saxon and High German loanwords can be estimated at 22–25 percent, with Low Saxon making up about 15 percent. Swedish and Russian are two other sources of borrowings but to a much lesser extent.[4]

Estonian is a predominantly agglutinative language. The loss of word-final sounds is extensive, and this has made its inflectional morphology markedly more fusional, especially with respect to noun and adjective inflection.[5] The transitional form from an agglutinating to a fusional language is a common feature of Estonian typologically over the course of history with the development of a rich morphological system.[6]

Word order is considerably more flexible than English, but the basic order is subject–verb–object.

History

The two different historical Estonian languages (sometimes considered dialects), the North and South Estonian languages, are based on the ancestors of modern Estonians' migration into the territory of Estonia in at least two different waves, both groups speaking considerably different Finnic vernaculars.[7] Modern standard Estonian has evolved on the basis of the dialects of Northern Estonia.

The oldest written records of the Finnic languages of Estonia date from the 13th century. Originates Livoniae in the Chronicle of Henry of Livonia contains Estonian place names, words and fragments of sentences.

Estonian literature

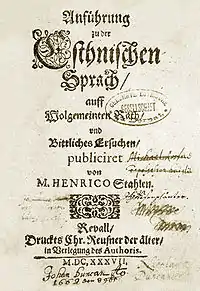

The earliest extant samples of connected (north) Estonian are the so-called Kullamaa prayers dating from 1524 and 1528.[8] In 1525 the first book published in the Estonian language was printed. The book was a Lutheran manuscript, which never reached the reader and was destroyed immediately after publication.

The first extant Estonian book is a bilingual German-Estonian translation of the Lutheran catechism by S. Wanradt and J. Koell dating to 1535, during the Protestant Reformation period. An Estonian grammar book to be used by priests was printed in German in 1637.[9] The New Testament was translated into southern Estonian in 1686 (northern Estonian, 1715). The two languages were united based on northern Estonian by Anton thor Helle.

Writings in Estonian became more significant in the 19th century during the Estophile Enlightenment Period (1750–1840).

The birth of native Estonian literature was in 1810 to 1820 when the patriotic and philosophical poems by Kristjan Jaak Peterson were published. Peterson, who was the first student at the then German-language University of Dorpat to acknowledge his Estonian origin, is commonly regarded as a herald of Estonian national literature and considered the founder of modern Estonian poetry. His birthday, March 14, is celebrated in Estonia as Mother Tongue Day.[10] A fragment from Peterson's poem "Kuu" expresses the claim reestablishing the birthright of the Estonian language:

- Kas siis selle maa keel

- Laulutuules ei või

- Taevani tõustes üles

- Igavikku omale otsida?

In English:

- Can the language of this land

- In the wind of incantation

- Rising up to the heavens

- Not seek for eternity?

- Kristjan Jaak Peterson

In the period from 1525 to 1917, 14,503 titles were published in Estonian; by comparison, between 1918 and 1940, 23,868 titles were published.

In modern times A. H. Tammsaare, Jaan Kross,[11] and Andrus Kivirähk are Estonia's best known and most translated writers.

State language

Writings in Estonian became significant only in the 19th century with the spread of the ideas of the Age of Enlightenment, during the Estophile Enlightenment Period (1750–1840). Although Baltic Germans at large regarded the future of Estonians as being a fusion with themselves, the Estophile educated class admired the ancient culture of the Estonians and their era of freedom before the conquests by Danes and Germans in the 13th century.[12]

In the aftermath of World War I, in 1918, the Estonian language became the official state language of the newly independent country. Immediately after World War II, in 1945, over 97% of the then population of Estonia self-identified as native ethnic Estonians[7] and spoke the language.

When Estonia was invaded and reoccupied by the Soviet army in 1944, the status of the Estonian language effectively changed to one of the two official languages (Russian being the other one).[13] Many immigrants from Russia entered Estonia under Soviet encouragement.[7] In the 1970s, the pressure of bilingualism for Estonians was intensified. Although teaching Estonian to non-Estonians in local schools was formally compulsory, in practice, the teaching and learning of the Estonian language by Russian-speakers was often considered unnecessary by the Soviet authorities.[7]

In 1991, with the restoration of Estonia's independence, Estonian went back to being the only state language in Estonia.[14]

The return of Soviet immigrants to their countries of origin has brought the proportion of Estonians in Estonia back above 70%. Many of the remnant non-Estonians in Estonia have adopted the Estonian language (about 40% as of the 2000 census).[7]

Dialects

The Estonian dialects[15][16] are divided into two groups – the northern and southern dialects, historically associated with the cities of Tallinn in the north and Tartu in the south, in addition to a distinct kirderanniku dialect, Northeastern coastal Estonian.

The northern group consists of the keskmurre or central dialect that is also the basis for the standard language, the läänemurre or western dialect, roughly corresponding to Lääne County and Pärnu County, the saarte murre (islands' dialect) of Saaremaa, Hiiumaa, Muhu and Kihnu, and the idamurre or eastern dialect on the northwestern shore of Lake Peipus.

South Estonian consists of the Tartu, Mulgi, Võro and Seto varieties. These are sometimes considered either variants of South Estonian or separate languages altogether.[17] Also, Seto and Võro distinguish themselves from each other less by language and more by their culture and their respective Christian confession.[7][18]

Writing system

Alphabet

Estonian employs the Latin script as the basis for its alphabet, which adds the letters ä, ö, ü, and õ, plus the later additions š and ž. The letters c, q, w, x and y are limited to proper names of foreign origin, and f, z, š, and ž appear in loanwords and foreign names only. Ö and Ü are pronounced similarly to their equivalents in Swedish and German. Unlike in standard German but like Swedish (when followed by 'r') and Finnish, Ä is pronounced [æ], as in English mat. The vowels Ä, Ö and Ü are clearly separate phonemes and inherent in Estonian, although the letter shapes come from German. The letter õ denotes /ɤ/, unrounded /o/, or a close-mid back unrounded vowel. It is almost identical to the Bulgarian ъ /ɤ̞/ and the Vietnamese ơ, and is also used to transcribe the Russian ы.

Orthography

Although the Estonian orthography is generally guided by phonemic principles, with each grapheme corresponding to one phoneme, there are some historical and morphological deviations from this: for example preservation of the morpheme in declension of the word (writing b, g, d in places where p, k, t is pronounced) and in the use of 'i' and 'j'. Where it is very impractical or impossible to type š and ž, they are replaced by sh and zh in some written texts, although this is considered incorrect. Otherwise, the h in sh represents a voiceless glottal fricative, as in Pasha (pas-ha); this also applies to some foreign names.

Modern Estonian orthography is based on the "Newer orthography" created by Eduard Ahrens in the second half of the 19th century based on Finnish orthography. The "Older orthography" it replaced was created in the 17th century by Bengt Gottfried Forselius and Johann Hornung based on standard German orthography. Earlier writing in Estonian had, by and large, used an ad hoc orthography based on Latin and Middle Low German orthography. Some influences of the standard German orthography – for example, writing 'W'/'w' instead of 'V'/'v' – persisted well into the 1930s.

Phonology

There are 9 vowels and 36 diphthongs, 28 of which are native to Estonian.[1] All nine vowels can appear as the first component of a diphthong, but only /ɑ e i o u/ occur as the second component. A vowel characteristic of Estonian is the unrounded back vowel /ɤ/, which may be close-mid back, close back, or close-mid central.

| Front | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unrounded | Rounded | Unrounded | Rounded | |

| Close | i | y | ɤ | u |

| Mid | e | ø | o | |

| Open | æ | ɑ | ||

| Labial | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Velar/ palatal |

Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | palatalized | ||||||

| Nasal | m | n | nʲ | ||||

| Plosive | short | p | t | tʲ | k | ||

| geminated | pː | tː | tʲː | kː | |||

| Fricative | voiced short | v | h | ||||

| voiceless short | f | s | sʲ | ʃ | |||

| geminated | fː | sː | sʲː | ʃː | hː | ||

| Approximant | l | lʲ | j | ||||

| Trill | r | ||||||

Word-initial b, d, g occur only in loanwords and are normally pronounced as [p], [t], [k]. Some old loanwords are spelled with p, t, k instead of etymological b, d, g: pank 'bank'. Word-medially and word-finally, b, d, g represent short plosives /p, t, k/ (may be pronounced as partially voiced consonants), p, t, k represent half-long plosives /pː, tː, kː/, and pp, tt, kk represent overlong plosives /pːː, tːː, kːː/; for example: kabi /kɑpi/ 'hoof' — kapi /kɑpːi/ 'wardrobe [gen sg] — kappi /kɑpːːi/ 'wardrobe [ine sg]'.

Before and after b, p, d, t, g, k, s, h, f, š, z, ž, the sounds [p], [t], [k] are written as p, t, k, with some exceptions due to morphology or etymology.

Representation of palatalised consonants is inconsistent, and they are not always indicated. ŋ is an allophone of /n/ before /k/.

While peripheral Estonian dialects are characterized by various degrees of vowel harmony, central dialects have almost completely lost the feature. Since the standard language is based on central dialects, it has no vowel harmony either. In the standard language, the front vowels occur exclusively on the first or stressed syllable, although vowel harmony is still apparent in older texts.[20]

Grammar

Typologically, Estonian represents a transitional form from an agglutinating language to a fusional language. The canonical word order is SVO (subject–verb–object).

In Estonian, nouns and pronouns do not have grammatical gender, but nouns and adjectives decline in fourteen cases: nominative, genitive, partitive, illative, inessive, elative, allative, adessive, ablative, translative, terminative, essive, abessive, and comitative, with the case and number of the adjective always agreeing with that of the noun (except in the terminative, essive, abessive and comitative, where there is agreement only for the number, the adjective being in the genitive form). Thus the illative for kollane maja ("a yellow house") is kollasesse majja ("into a yellow house"), but the terminative is kollase majani ("as far as a yellow house"). With respect to the Proto-Finnic language, elision has occurred; thus, the actual case marker may be absent, but the stem is changed, cf. maja – majja and the Ostrobothnia dialect of Finnish maja – majahan.

The verbal system lacks a distinctive future tense[21] (the present tense serves here) and features special forms to express an action performed by an undetermined subject (the "impersonal").

Vocabulary

Although the Estonian and Germanic languages are of very different origins and the vocabulary is considered quite different from that of the Indo-European family,[6] one can identify many similar words in Estonian and English, for example. This is primarily because the Estonian language has borrowed nearly one-third of its vocabulary from Germanic languages, mainly from Low Saxon (Middle Low German) during the period of German rule, and High German (including standard German). The percentage of Low Saxon and High German loanwords can be estimated at 22–25 percent, with Low Saxon making up about 15 percent.[22]

Often 'b' and 'p' are interchangeable, for example 'baggage' becomes 'pagas', 'lob' (to throw) becomes 'loopima'. The initial letter 's' before another consonant is often dropped, for example 'skool' becomes 'kool', 'stool' becomes 'tool'.

Ex nihilo lexical enrichment

Estonian language planners such as Ado Grenzstein (a journalist active in Estonia in the 1870s–90s) tried to use formation ex nihilo (Urschöpfung);[23] i.e. they created new words out of nothing.

The most famous reformer of Estonian, Johannes Aavik (1880–1973), used creations ex nihilo (cf. 'free constructions', Tauli 1977), along with other sources of lexical enrichment such as derivations, compositions and loanwords (often from Finnish; cf. Saareste and Raun 1965: 76). In Aavik's dictionary (1921), which lists approximately 4000 words, there are many words that were (allegedly) created ex nihilo, many of which are in common use today. Examples are

- ese 'object',

- kolp 'skull',

- liibuma 'to cling',

- naasma 'to return, come back',

- nõme 'stupid, dull'[23]

Many of the coinages that have been considered (often by Aavik himself) as words concocted ex nihilo could well have been influenced by foreign lexical items, for example words from Russian, German, French, Finnish, English and Swedish. Aavik had a broad classical education and knew Ancient Greek, Latin and French. Consider roim 'crime' versus English crime or taunima 'to condemn, disapprove' versus Finnish tuomita 'to condemn, to judge' (these Aavikisms appear in Aavik's 1921 dictionary). These words might be better regarded as a peculiar manifestation of morpho-phonemic adaptation of a foreign lexical item.[24]

Example text

Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Estonian:

- Kõik inimesed sünnivad vabadena ja võrdsetena oma väärikuselt ja õigustelt. Neile on antud mõistus ja südametunnistus ja nende suhtumist üksteisesse peab kandma vendluse vaim.[25]

Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in English:

- All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.[26]

See also

- The BABEL Speech Corpus

References

- Estonian at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

Standard Estonian at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

Võro at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required) - "Estonian in a World Context". Estonica. Archived from the original on 2018-09-27. Retrieved 2018-09-26.

- "The Estonian Language". Estonica.org. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- "Eesti keele käsiraamat 2007". Eesti Keele Instituut (in Estonian). Retrieved 2020-09-30.

- Ehala, Martin (2009). "Linguistic Strategies and Markedness in Estonian Morphology". STUF – Language Typology and Universals. 62 (1–2): 29–48. doi:10.1524/stuf.2009.0003. S2CID 121233571.

- Rehm, Georg; Uszkoreit, Hans (2012). Language Technology Support for Estonian. White Paper Series. Berlin: Springer. pp. 47–64. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-30785-0_9. ISBN 978-3-642-30784-3.

- Rannut, Mart (2004). "Language Policy in Estonia". Noves SL.: Revista de sociolingüística (in Spanish) (1–2 (primavera – estiu)): 4.

- Kurman, George (1997). The Development of Written Estonian. London: RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 9780700708901.

- Dalby, Andrew (2004). Dictionary of Languages: The Definitive Reference to More Than 400 Languages (rev. ed.). New York: Columbia University Press. p. 182. ISBN 0-231-11569-5.

- O'Connor, Kevin (2006). Culture and Customs of the Baltic States. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 126. ISBN 0-313-33125-1.

- Jaan Kross at Google Books

- Jansen, Ea (2004). "The National Awakening of the Estonian Nation". In Subrenat, Jean-Jacques (ed.). Estonia: Identity and Independence. Translated by Cousins, David; Dickens, Eric; Harding, Alexander; Waterhouse, Richard C. Rodopi. p. 84. ISBN 90-420-0890-3.

- Baker, Colin; Jones, Sylvia Prys (1998). Encyclopedia of Bilingualism and Bilingual Education. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. p. 207. ISBN 1-85359-362-1.

- Leclerc, Jacques. "Estonie". L'aménagement linguistique dans le monde (in French). Archived from the original on 2012-11-11. Retrieved 2014-08-23.

- "[Map of Estonian Dialects]". Archived from the original on 2014-08-26. Retrieved 2014-08-23 – via Tartu University's Estonian Dialect Corpus.

- see Tartu University's Estonian Dialect Corpus website

- "Culture Tourism in South Estonia and Võru County: Situation Analysis" (PDF). Retrieved 2 July 2013 – via Siksali.

- "Eesti murded / Estonian Dialects". Eesti Keele Instituut (in Estonian). Archived from the original on 2014-08-26. Retrieved 2014-08-23.

- Asu & Teras (2009:367)

- Prillop, Külli et al. 2020. Eesti keele ajalugu. Tartu Ülikooli Kirjastus. p. 133.

- Pérez, Efrén O.; Tavits, Margit (2017). "Language Shapes People's Time Perspective and Support for Future-Oriented Policies". American Journal of Political Science. 61 (3): 715–727. doi:10.1111/ajps.12290.

- "Eesti kirjakeele sõnavara ajalugu" [History of Estonian Vocabulary]. FILLU (in Estonian). Archived from the original on 2007-07-21.

- Zuckermann, Ghil'ad (2003). Language Contact and Lexical Enrichment in Israeli Hebrew. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 149. ISBN 978-1-4039-1723-2.

- Zuckermann, Ghil'ad (2003). Language Contact and Lexical Enrichment in Israeli Hebrew. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 150. ISBN 978-1-4039-1723-2.

- Estonian Human Rights Institute, Estonia. "Universal Declaration of Human Rights – Estonian (Eesti)". Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Retrieved 2021-09-13.

- "Universal Declaration of Human Rights". un.org.

Further reading

- Asu, Eva Liina; Teras, Pire (2009). "Estonian". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 39 (3): 367–372. doi:10.1017/s002510030999017x.

- Ross, Jaan; Lehiste, Ilse (2001). The Temporal Structure of Estonian Runic Songs. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-017032-9.

- Soosaar, Sven-Erik (2013). "The Origins of Stems of Standard Estonian – a Statistical Overview". TRAMES: A Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences. 17 (3): 273–300. doi:10.3176/tr.2013.3.04.

.png.webp)