Palais Garnier

The Palais Garnier (French: [palɛ ɡaʁnje] (![]() listen), Garnier Palace), also known as Opéra Garnier (French: [ɔpeʁa ɡaʁnje] (

listen), Garnier Palace), also known as Opéra Garnier (French: [ɔpeʁa ɡaʁnje] (![]() listen), Garnier Opera), is a 1,979-seat[3] opera house at the Place de l'Opéra in the 9th arrondissement of Paris, France. It was built for the Paris Opera from 1861 to 1875 at the behest of Emperor Napoleon III.[4] Initially referred to as le nouvel Opéra de Paris (the new Paris Opera), it soon became known as the Palais Garnier,[5] "in acknowledgment of its extraordinary opulence"[6] and the architect Charles Garnier's plans and designs, which are representative of the Napoleon III style. It was the primary theatre of the Paris Opera and its associated Paris Opera Ballet until 1989, when a new opera house, the Opéra Bastille, opened at the Place de la Bastille.[7] The company now uses the Palais Garnier mainly for ballet. The theatre has been a monument historique of France since 1923.

listen), Garnier Opera), is a 1,979-seat[3] opera house at the Place de l'Opéra in the 9th arrondissement of Paris, France. It was built for the Paris Opera from 1861 to 1875 at the behest of Emperor Napoleon III.[4] Initially referred to as le nouvel Opéra de Paris (the new Paris Opera), it soon became known as the Palais Garnier,[5] "in acknowledgment of its extraordinary opulence"[6] and the architect Charles Garnier's plans and designs, which are representative of the Napoleon III style. It was the primary theatre of the Paris Opera and its associated Paris Opera Ballet until 1989, when a new opera house, the Opéra Bastille, opened at the Place de la Bastille.[7] The company now uses the Palais Garnier mainly for ballet. The theatre has been a monument historique of France since 1923.

Opéra Garnier | |

View of the principal façade of the Palais Garnier from the Place de l'Opéra | |

| |

| Former names | Nouvel Opéra de Paris |

|---|---|

| Address | Place de l'Opéra 75009 Paris France |

| Coordinates | 48°52′19″N 2°19′54″E |

| Public transit | |

| Type | Opera house |

| Capacity | 1,979 |

| Construction | |

| Broke ground | August 1861[1] |

| Opened | 5 January 1875 |

| Construction cost | 36,010,571.04 francs (as of 20 November 1875)[2] |

| Architect | Charles Garnier |

| Tenants | |

| Paris National Opera | |

| Website | |

| operadeparis.fr | |

Monument historique | |

| Designated | 16 October 1923 |

| Reference no. | PA00089004 |

The Palais Garnier has been called "probably the most famous opera house in the world, a symbol of Paris like Notre Dame Cathedral, the Louvre, or the Sacré Coeur Basilica."[8] This is at least partly due to its use as the setting for Gaston Leroux's 1910 novel The Phantom of the Opera and, especially, the novel's subsequent adaptations in films and the popular 1986 musical.[8] Another contributing factor is that among the buildings constructed in Paris during the Second Empire, besides being the most expensive,[9] it has been described as the only one that is "unquestionably a masterpiece of the first rank."[10] This opinion is far from unanimous however: the 20th-century French architect Le Corbusier once described it as "a lying art" and contended that the "Garnier movement is a décor of the grave".[11]

The Palais Garnier also houses the Bibliothèque-Musée de l'Opéra de Paris (Paris Opera Library-Museum), which is managed by the Bibliothèque Nationale de France[12] and is included in unaccompanied tours of the Palais Garnier.[13]

Dimensions and technical details

The Palais Garnier is 56 metres (184 ft) from ground level to the apex of the stage flytower; 32 metres (105 ft) to the top of the facade.[14]

The building is 154.9 metres (508 ft) long; 70.2 metres (230 ft) wide at the lateral galleries; 101.2 metres (332 ft) wide at the east and west pavilions; 10.13 metres (33.2 ft) from ground level to bottom of the cistern under the stage.[15]

The structural system is made of masonry walls; concealed iron floors, vaults, and roofs.[16]

Architecture and style

The opera was constructed in what Charles Garnier (1825–1898) is said to have told the Empress Eugenie was "Napoleon III" style[17] The Napoleon III style was highly eclectic, and borrowed from many historical sources; the opera house included elements from the Baroque, the classicism of Palladio, and Renaissance architecture blended together.[18] These were combined with axial symmetry and modern techniques and materials, including the use of an iron framework, which had been pioneered in other Napoleon III buildings, including the Bibliothèque Nationale and the markets of Les Halles.[19][20]

- Plans of the Palais Garnier

Plan of the ground floor

Plan of the ground floor Plan of the main floor

Plan of the main floor Plan at the auditorium ceiling level

Plan at the auditorium ceiling level Plan of the roof

Plan of the roof

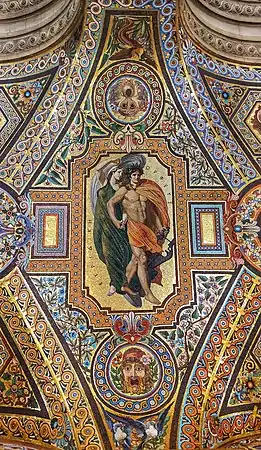

The façade and the interior followed the Napoleon III style principle of leaving no space without decoration.[19] Garnier used polychromy, or a variety of colors, for theatrical effect, achieved different varieties of marble and stone, porphyry, and gilded bronze. The façade of the Opera used seventeen different kinds of material, arranged in very elaborate multicolored marble friezes, columns, and lavish statuary, many of which portray deities of Greek mythology.[19]

Main façade

The principal façade is on the south side of the building, overlooking the Place de l'Opéra and terminates the perspective along the Avenue de l'Opéra. Fourteen painters, mosaicists and seventy-three sculptors participated in the creation of its ornamentation.[21]

The two gilded figural groups, Charles Gumery's L'Harmonie (Harmony) and La Poésie (Poetry), crown the apexes of the principal façade's left and right avant-corps. They are both made of gilt copper electrotype.[22]

The bases of the two avant-corps are decorated (from left to right) with four major multi-figure groups sculpted by François Jouffroy (Poetry, also known as Harmony),[23] Jean-Baptiste Claude Eugène Guillaume (Instrumental Music), Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux (The Dance, criticised for indecency), and Jean-Joseph Perraud (Lyrical Drama). The façade also incorporates other work by Gumery, Alexandre Falguière, and others.[24]

Gilded galvanoplastic bronze busts of many of the great composers are located between the columns of the theatre's front façade and depict, from left to right, Rossini, Auber, Beethoven, Mozart, Spontini, Meyerbeer, and Halévy. On the left and right lateral returns of the front façade are busts of the librettists Eugène Scribe and Philippe Quinault, respectively.[24]

- Exterior artwork

Gumery's L'Harmonie (1869), atop the left avant-corps of the façade, is 7.5 metres (25 ft) of gilt copper electrotype

Gumery's L'Harmonie (1869), atop the left avant-corps of the façade, is 7.5 metres (25 ft) of gilt copper electrotype Apollo, Poetry and Music roof sculpture by Aimé Millet

Apollo, Poetry and Music roof sculpture by Aimé Millet Apollo, Poetry and Music; Apollo's lyre detail

Apollo, Poetry and Music; Apollo's lyre detail Poetry roof sculpture by Charles Gumery

Poetry roof sculpture by Charles Gumery Lyrical Drama façade sculpture by Jean-Joseph Perraud

Lyrical Drama façade sculpture by Jean-Joseph Perraud The Dance by Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux

The Dance by Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux Bronze busts of Beethoven and Mozart on the front façade

Bronze busts of Beethoven and Mozart on the front façade

Stage flytower

The sculptural group Apollo, Poetry, and Music, located at the apex of the south gable of the stage flytower, is the work of Aimé Millet, and the two smaller bronze Pegasus figures at either end of the south gable are by Eugène-Louis Lequesne.

Pavillon de l'Empereur

Also known as the Rotonde de l'Empereur, this group of rooms is located on the left (west) side of the building and was designed to allow secure and direct access by the Emperor via a double ramp to the building. When the Empire fell, work stopped, leaving unfinished dressed stonework. It now houses the Bibliothèque-Musée de l'Opéra de Paris (Paris Opera Library-Museum) which is home to nearly 600,000 documents including 100,000 books, 1,680 periodicals, 10,000 programs, letters, 100,000 photographs, sketches of costumes and sets, posters and historical administrative records.

Pavillon des Abonnés

Located on the right (east) side of the building as a counterpart to the Pavillon de l'Empereur, this pavilion was designed to allow subscribers (abonnés) direct access from their carriages to the interior of the building. It is covered by a 13.5-metre (44-ft) diameter dome. Paired obelisks mark the entrances to the rotunda on the north and the south.

%252C_2014-07-05.jpg.webp) East façade and the Pavillon des Abonnés

East façade and the Pavillon des Abonnés.jpg.webp) West façade and the Pavillon de l'Empereur

West façade and the Pavillon de l'Empereur

Interior

The interior consists of interweaving corridors, stairwells, alcoves and landings, allowing the movement of large numbers of people and space for socialising during intermission. Rich with velvet, gold leaf, and cherubim and nymphs, the interior is characteristic of Baroque sumptuousness.

Grand staircase

The building features a large ceremonial staircase of white marble with a balustrade of red and green marble, which divides into two divergent flights of stairs that lead to the Grand Foyer. Its design was inspired by Victor Louis's grand staircase for the Théâtre de Bordeaux. The pedestals of the staircase are decorated with female torchères, created by Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse. The ceiling above the staircase was painted by Isidore Pils to depict The Triumph of Apollo, The Enchantment of Music Deploying its Charms, Minerva Fighting Brutality Watched by the Gods of Olympus, and The City of Paris Receiving the Plan of the New Opéra. When the paintings were first fixed in place two months before the opening of the building, it was obvious to Garnier that they were too dark for the space. With the help of two of his students, Pils had to rework the canvases while they were in place overhead on the ceiling and, at the age of 61, he fell ill. His students had to finish the work, which was completed the day before the opening and the scaffolding was removed.[25]

Louis Béroud: L'escalier de l'opéra Garnier, 1877 (Musée Carnavalet)

Louis Béroud: L'escalier de l'opéra Garnier, 1877 (Musée Carnavalet) Engraving from Garnier's Nouvel Opéra, 1880

Engraving from Garnier's Nouvel Opéra, 1880 The grand staircase of the Palais Garnier

The grand staircase of the Palais Garnier The grand staircase

The grand staircase The Amphitheater Entrance

The Amphitheater Entrance

Grand foyer

This hall, 18 metres (59 ft) high, 54 metres (177 ft) long and 13 metres (43 ft) wide, was designed to act as a drawing room for Paris society. It was restored in 2004. Its ceiling was painted by Paul-Jacques-Aimé Baudry and represents various moments in the history of music. The foyer opens onto an outside loggia and is flanked by two octagonal salons with ceilings painted by Jules-Élie Delaunay in the eastern salon and Félix-Joseph Barrias in the western salon. The octagonal salons open to the north into the Salon de la Lune at the western end of the Avant-Foyer and the Salon du Soleil at its eastern end.[26]

View of the Grand Foyer looking west

View of the Grand Foyer looking west View of the Grand Foyer looking east

View of the Grand Foyer looking east Part of the ceiling of the Grand Foyer with paintings by Paul Baudry: the central rectangular panel is Music, while the oval panel at the western end is Comedy.[26]

Part of the ceiling of the Grand Foyer with paintings by Paul Baudry: the central rectangular panel is Music, while the oval panel at the western end is Comedy.[26] Ceiling of the octagonal salon at the eastern end with Jules-Élie Delaunay's central oval panel, The Zodiac, and over-door panel, Apollo Receiving the Lyre[26]

Ceiling of the octagonal salon at the eastern end with Jules-Élie Delaunay's central oval panel, The Zodiac, and over-door panel, Apollo Receiving the Lyre[26]

The four pair mosaic panels

The four medallions

There are four bronze gilt medallions representing musical instruments from Egypt, Greece, Italy and France[27] which are surrounded by wreaths of leaves and flowers and have the name of the countries in Greek (Egypt=ΑΙΓΥΠΤΟΣ, Greece=ΕΛΛΑΣ, Italy=ΙΤΑΛΙΑ and France=ΓΑΛΛΙΑ).[28]

Egypt medallion

Egypt medallion Greece medallion

Greece medallion Italy medallion

Italy medallion France medallion

France medallion

Muses and personifications

Thalia (top, Muse of comedy), Epithumia (bottom left, meaning desire) and Pistis (bottom right, meaning good faith, trust and reliability), their names are in Greek. Thalia = ΘΑΛΕΙΑ, Epithumia = Η ΕΠΙΘΥΜΙΑ and Pistis = Η ΠΙΣΤΙΣ

Melpomene (top, Muse of tragedy), Sophrosyne (bottom left, meaning excellence of character and soundness of mind) and Elpis (bottom right, meaning hope), their names are in Greek. Melpomene = ΜΕΛΠΟΜΕΝΗ, Elpis = Η ΕΛΠΙΣ and Sophrosyne = Η ΣΩΦΡΟΣΥΝΗ

Terpsichore (top, Muse of dance), Autonomia (bottom left, meaning autonomy) and Phantasia (bottom right, meaning imagination), their names are in Greek. Terpsichore = ΤΕΡΨΙΧΟΡΗ, Autonomia = Η ΑΥΤΟΝΟΜΙΑ and Phantasia = H ΦΑΝΤΑΣΙΑ

Erato (top, the Muse of lyric poetry), Rhome (bottom left, meaning strength) and Sophia (bottom right, meaning wisdom), their names are in Greek. Erato = ΕΡΑΤΩ, Rhome = Η ΡΩΜΗ and Sophia = Η ΣΟΦΙΑ

Calliope (top, Muse of eloquence and epic poetry), Dianoia (bottom left, meaning thinking) and Euprepia (bottom right, meaning preeminent beauty), their names are in Greek. Calliope = ΚΑΛΛΙΟΠΗ, Dianoia = Η ΔΙΑΝΟΙΑ and Euprepia = Η ΕΥΠΡΕΠΕΙΑ

Urania (top, Muse of astronomy), Diadochi (bottom left, meaning succession) and Episteme (bottom right, meaning to know, to understand, to be acquainted with), their names are in Greek. Urania = ΟΥΡΑΝΙΑ, Diadochi = Η ΔΙΑΔΟΧΗ and Episteme = Η ΕΠΙΣΤΗΜΗ

Euterpe (top, Muse of music), Kalossyni (bottom left, meaning kindness, charity) and Charis (bottom right, meaning grace), their names are in Greek. Euterpe = ΕΥΤΕΡΠΗ, Kalossyni = Η ΚΑΛΛΟΣΥΝΗ and Charis = Η ΧΑΡΙΣ

Clio (top, Muse of history), Boulesis (bottom left, meaning will) and Phronesis (bottom right, meaning prudence, practical virtue and practical wisdom), their names are in Greek. Clio = ΚΛΕΙΩ, Boulesis = Η ΒΟΥΛΗΣΙΣ and Phronesis = Η ΦΡΟΝΗΣΙΣ

Auditorium

The auditorium has a traditional Italian horseshoe shape and can seat 1,979. The stage is the largest in Europe and can accommodate as many as 450 artists. The canvas house curtain was painted to represent a draped curtain, complete with tassels and braid.

Auditorium

Auditorium Transverse section at the auditorium and pavilions

Transverse section at the auditorium and pavilions Auditorium. Postcard from 1909

Auditorium. Postcard from 1909

The ceiling area which surrounds the chandelier was originally painted by Jules-Eugène Lenepveu. In 1964 a new ceiling painted by Marc Chagall was installed on a removable frame over the original. It depicts scenes from operas by 14 composers – Mussorgsky, Mozart, Wagner, Berlioz, Rameau, Debussy, Ravel, Stravinsky, Tchaikovsky, Adam, Bizet, Verdi, Beethoven, and Gluck. Although praised by some, others feel Chagall's work creates "a false note in Garnier's carefully orchestrated interior."[29]

Chandelier

The seven-ton bronze and crystal chandelier was designed by Garnier. Jules Corboz prepared the model, and it was cast and chased by Lacarière, Delatour & Cie. The total cost came to 30,000 gold francs. The use of a central chandelier aroused controversy, and it was criticised for obstructing views of the stage by patrons in the fourth level boxes and views of the ceiling painted by Lenepveu.[30] Garnier had anticipated these disadvantages but provided a lively defence in his 1871 book Le Théâtre: "What else could fill the theatre with such joyous life? What else could offer the variety of forms that we have in the pattern of the flames, in these groups and tiers of points of light, these wild hues of gold flecked with bright spots, and these crystalline highlights?"[31]

.jpg.webp) Final model for the ceiling painted by Jules-Eugène Lenepveu

Final model for the ceiling painted by Jules-Eugène Lenepveu Auditorium chandelier

Auditorium chandelier Lighted chandelier under the ceiling by Marc Chagall

Lighted chandelier under the ceiling by Marc Chagall

On 20 May 1896, one of the chandelier's counterweights broke free and burst through the ceiling into the auditorium, killing a concierge. This incident inspired one of the more famous scenes in Gaston Leroux's classic 1910 gothic novel The Phantom of the Opera.[30]

Originally the chandelier was raised up through the ceiling into the cupola over the auditorium for cleaning, but now it is lowered. The space in the cupola was used in the 1960s for opera rehearsals, and in the 1980s was remodelled into two floors of dance rehearsal space. The lower floor consists of the Salle Nureïev (Nureyev) and the Salle Balanchine, and the upper floor, the Salle Petipa.[30]

Organ

The grand organ was built by Aristide Cavaillé-Coll for use during lyrical works. It has been out of service for several decades.

Restaurant

Garnier had originally planned to install a restaurant in the opera house; however, for budgetary reasons, it was not completed in the original design.

On the third attempt to introduce it since 1875, a restaurant was opened on the eastern side of the building in 2011. L'Opéra Restaurant was designed by French architect Odile Decq. The chef was Christophe Aribert;[32] in October 2015, Guillame Tison-Malthé became the new head chef.[33] The restaurant, which has three different spaces and a large outside terrace, is accessible to the general public.

Palais Garnier east side with L'Opéra Restaurant

Palais Garnier east side with L'Opéra Restaurant L'Opéra Restaurant opened in 2011

L'Opéra Restaurant opened in 2011

History

Selection of a site

In 1821 the Opéra de Paris had moved into the temporary building known as the Salle Le Peletier on the rue Le Peletier. Since then a new permanent building had been desired. Charles Rohault de Fleury, who was appointed the opera's official architect in 1846, undertook various studies in suitable sites and designs.[34] By 1847, the Prefect of the Seine, Claude-Philibert de Rambuteau, had selected a site on the east side of the Place du Palais-Royal as part of an extension of the Rue de Rivoli. However, with the Revolution of 1848, Rambuteau was dismissed, and interest in the construction of a new opera house waned. The site was later used for the Grand Hôtel du Louvre (designed in part by Charles Rohault de Fleury).[35]

With the establishment of the Second Empire in 1852 and Georges-Eugène Haussmann's appointment as Prefect of the Seine in June 1853, interest in a new opera house revived. There was an attempted assassination of Emperor Napoleon III at the entrance to the Salle Le Peletier on 14 January 1858. The Salle Le Peletier's constricted street access highlighted the need for a separate, more secure entrance for the head of state. This concern and the inadequate facilities and temporary nature of the theatre gave added urgency to the building of a new state-funded opera house. By March, Haussmann settled on Rohault de Fleury's proposed site off the Boulevard des Capucines, although this decision was not announced publicly until 1860. A new building would help resolve the awkward convergence of streets at this location, and the site was economical in terms of the cost of land.[36]

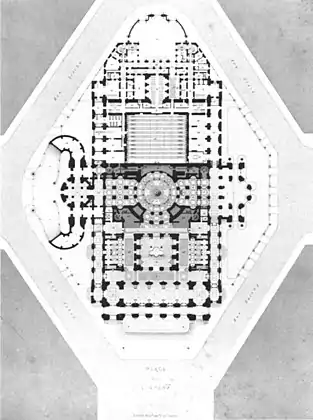

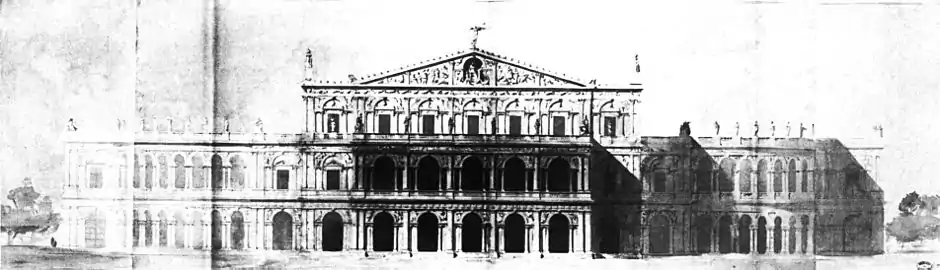

On 29 September 1860 an Imperial Decree officially designated the site for the new Opéra,[37] which would eventually occupy 12,000 square metres (1.2 ha; 130,000 sq ft).[3] By November 1860 Rohault de Fleury had completed the design for what he thought would be the crowning work of his career and was also working on a commission from the city to design the façades of the other buildings lining the new square to ensure they were in harmony. However, that same month Achille Fould was replaced as Minister of State by Count Alexandre Colonna-Walewski. His wife Marie Anne de Ricci Poniatowska had used her position as mistress of Napoleon III to obtain her husband's appointment.[38] Aware of competing designs and under pressure to give the commission to Viollet-le-Duc, who had the support of Empress Eugénie, Walewski escaped the need to make a decision by proposing to mount an architectural design competition to select the architect.[39]

Entrance elevation of a project for the Théâtre Impériale de l'Opéra by Rohault de Fleury, November 1860

Entrance elevation of a project for the Théâtre Impériale de l'Opéra by Rohault de Fleury, November 1860 Plan

Plan

Design competition

On 30 December 1860 the Second Empire of Emperor Napoleon III officially announced an architectural design competition for the design of the new opera house.

Applicants were given a month to submit entries. There were two phases to the competition. Charles Garnier's project was one of about 170 submitted in the first phase.[40] Each of the entrants was required to submit a motto that summarised their design. Garnier's was the quote "Bramo assai, poco spero" ("Hope for much, expect little") from the Italian poet Torquato Tasso. Garnier's project was awarded the fifth-place prize, and he became one of seven finalists selected for the second phase.[41] In addition to Garnier, among the others were his friend Leon Ginain, Alphonse-Nicolas Crépinet and Joseph-Louis Duc (who subsequently withdrew due to other commitments).[42] To the surprise of many, both Viollet-le-Duc and Charles Rohault de Fleury missed out.

- Viollet-de-Duc's losing Opera Competition project of 1861

Perspective view

Perspective view Plan

Plan Long section

Long section

The second phase required the contestants to revise their original projects and was more rigorous, with a 58-page program, written by the director of the Opéra, Alphonse Royer, which the contestants received on 18 April. The new submissions were sent to the jury in the middle of May, and on 29 May 1861 Garnier's project was selected for its "rare and superior qualities in the beautiful distribution of the plans, the monumental and characteristic aspect of the facades and sections".[43]

Garnier's wife Louise later wrote that the French architect Alphonse de Gisors, who was on the jury, had commented to them that Garnier's project was "remarkable in its simplicity, clarity, logic, grandeur, and because of the exterior dispositions which distinguish the plan in three distinct parts—the public spaces, auditorium, and stage ... 'you have greatly improved your project since the first competition; whereas Ginain [the first-place winner in the first phase] has ruined his.'"[43]

Legend has it that the Emperor's wife, the Empress Eugénie, who was likely irritated that her own favoured candidate, Viollet-le-Duc, had not been selected, asked the relatively unknown Garnier: "What is this? It's not a style; it's neither Louis Quatorze, nor Louis Quinze, nor Louis Seize!" "Why Ma'am, it's Napoléon Trois" replied Garnier "and you're complaining!"[44] Andrew Ayers has written that Garnier's definition "remains undisputed, so much does the Palais Garnier seem emblematic of its time and of the Second Empire that created it. A giddy mixture of up-to-the-minute technology, rather prescriptive rationalism, exuberant eclecticism and astonishing opulence, Garnier's opera encapsulated the divergent tendencies and political and social ambitions of its era."[45] Ayers goes on to say that the judges of the competition in particular admired Garnier's design for "the clarity of his plan, which was a brilliant example of the beaux-arts design methods in which both he and they were thoroughly versed."[45]

Opéra Agence

After the initial funds to begin construction were voted on 2 July 1861, Garnier established the Opéra Agence, his office on the construction site, and hired a team of architects and draftsmen. He selected as his second-in-command, Louis-Victor Louvet, followed by Jean Jourdain and Edmond Le Deschault.[47]

Laying of the foundation

The site was excavated between 27 August and 31 December.[48] On 13 January 1862 the first concrete foundations were poured, starting at the front and progressing sequentially toward the back, with the laying of the substructure masonry beginning as soon as each section of concrete was cast. The opera house needed a much deeper basement in the substage area than other building types, but the level of the groundwater was unexpectedly high. Wells were sunk in February 1862 and eight steam pumps installed in March, but despite operating continuously 24 hours a day, the site would not dry up. To deal with this problem Garnier designed a double foundation to protect the superstructure from moisture. It incorporated a water course and an enormous concrete cistern (cuve) which would both relieve the pressure of the external groundwater on the basement walls and serve as a reservoir in case of fire. A contract for its construction was signed on 20 June. Soon a persistent legend arose that the opera house was built over a subterranean lake, inspiring Gaston Leroux to incorporate the idea into his novel The Phantom of the Opera. On 21 July the cornerstone was laid at the southeast angle of the building's facade. In October the pumps were removed, the brick vault of the cuve was finished by 8 November, and the substructure was essentially complete by the end of the year.[49]

Model

The emperor expressed an interest in seeing a model of the building, and a plaster scale model (2 cm per meter) was constructed by Louis Villeminot between April 1862 and April 1863 at a cost of more than 8,000 francs. After previewing it, the emperor requested several changes to the design of the building, the most important of which was the suppression of a balustraded terrace with corner groups at the top of the facade and its replacement with a massive attic story fronted by a continuous frieze surmounted by imperial quadrigae over the end bays.[50]

With the incorporated changes, the model was transported over specially installed rails to the Palais de l'Industrie for public display at the 1863 exhibition. Théophile Gautier wrote of the model (Le Moniteur Universel, 13 May 1863) that "the general arrangement becomes intelligible to all eyes and already acquires a sort of reality that better permits one to prejudge the final effect ... it attracts the crowd's curiosity; it is, in effect, the new Opéra seen through reversed opera glasses."[51] The model is now lost, but it was photographed by J. B. Donas in 1863.[50]

The emperor's quadrigae were never added, although they can be seen in the model. Instead Charles-Alphonse Guméry's gilded bronze sculptural groups Harmony and Poetry were installed in 1869. The linear frieze seen in the model was also redesigned with alternating low- and high-relief decorative medallions bearing the gilded letters from the imperial monogram ("N" for Napoléon, "E" for Empereur). The custom-designed letters were not ready in time for the unveiling and were replaced with commercially available substitutes. After the fall of the empire in 1870, Garnier was relieved to be able to remove them from the medallions. Letters in Garnier's original design were finally installed during the restoration of the building in 2000.[52]

Change in name

The scaffolding concealing the facade was removed on 15 August 1867 in time for the Paris Exposition of 1867. The official title of the Paris Opera was prominently displayed on the entablature of the giant Corinthian order of coupled columns fronting the main-floor loggia: "ACADEMIE IMPERIALE DE MUSIQUE".[53] When the emperor was deposed on 4 September 1870 as a result of the disastrous Franco-Prussian War, the government was replaced by the Third Republic, and almost immediately, on 17 September 1870, the Opera was renamed Théâtre National de l'Opéra, a name it kept until 1939.[54] In spite of this, when it came time to change the name on the new opera house, only the first six letters of the word IMPERIALE were replaced, giving the now famous "ACADEMIE NATIONALE DE MUSIQUE", an official title which had actually only been used during the approximately two-year period of the Second Republic which had preceded the Second Empire.[54]

1870–1871

All work on the building came to a halt during the Franco-Prussian War due to the siege of Paris (September 1870 – January 1871). Construction had so advanced that parts of the building could be used as a food warehouse and a hospital. After France's defeat Garnier became seriously ill from the deprivations of the siege and left Paris from March to June to recover on the Ligurian coast of Italy, while his assistant Louis Louvet remained behind during the turmoil of the Paris Commune which followed. Louvet wrote several letters to Garnier, which document events relating to the building. Because of the theatre's proximity to the fighting at the Place Vendôme, troops of the National Guard bivouacked there and were in charge of its defence and distributing food to soldiers and civilians. The Commune authorities planned to replace Garnier with another architect, but this unnamed man had not yet appeared when Republican troops ousted the National Guard and gained control over the building on 23 May. By the end of the month the Commune had been severely defeated. The Third Republic had become sufficiently well established by the fall, that on 30 September construction work recommenced, and by late October a small amount of funds were voted by the new legislature for further construction.[55]

1872–1873

The political leaders of the new government maintained an intense dislike of all things associated with the Second Empire, and many of them regarded the essentially apolitical Garnier as a holdover from that regime. This was especially true during the presidency of Adolphe Thiers who remained in office until May 1873, but also persisted under his successor Marshal MacMahon. Economies were demanded, and Garnier was forced to suppress the completion of sections of the building, in particular the Pavillon de l'Empereur (which later became the home of the Opera Library Museum). However, on 28–29 October an overwhelming incentive to complete the new theatre came when the Salle Le Peletier was destroyed by a fire which raged the entire night.[56] Garnier was immediately instructed to complete the building as soon as possible.

Completion

.jpg.webp)

The cost of completion of the new house during 1874 was more than 7.5 million francs, a sum that greatly exceeded the amounts spent in any of the previous thirteen years. The cash-strapped government of the Third Republic resorted to borrowing 4.9 million gold francs at an interest rate of six percent from François Blanc, the wealthy financier who managed the Monte Carlo Casino. Subsequently (from 1876 to 1879) Garnier would oversee the design and construction of the Monte Carlo Casino concert hall, the Salle Garnier, which later became the home of the Opéra de Monte Carlo.[57]

During 1874 Garnier and his construction team worked feverishly to complete the new Paris opera house, and by 17 October the orchestra was able to conduct an acoustical test of the new auditorium, followed by another on 2 December which was attended by officials, guests, and members of the press. The Paris Opera Ballet danced on the stage on 12 December, and six days later the famous chandelier was lit for the first time.[58]

The theatre was formally inaugurated on 5 January 1875 with a lavish gala performance attended by Marshal MacMahon, the Lord Mayor of London and King Alfonso XII of Spain. The program included the overtures to Auber's La muette de Portici and Rossini's William Tell, the first two acts of Halévy's 1835 opera La Juive (with Gabrielle Krauss in the title role), along with "The Consecration of the Swords" from Meyerbeer's 1836 opera Les Huguenots and the 1866 ballet La source with music by Delibes and Minkus.[59] As a soprano had fallen ill one act from Charles Gounod's Faust and one from Ambroise Thomas's Hamlet had to be omitted. During the intermission Garnier stepped out onto the landing of the grand staircase to receive the approving applause of the audience.

History of the house since opening

In 1881 electric lighting was installed. [60] In the 1950s new personnel and freight elevators were installed at the rear of stage, to facilitate the movement of employees in the administration building and the moving of stage scenery.

In 1969, the theatre was given new electrical facilities and, during 1978, part of the original Foyer de la Danse was converted into new rehearsal space for the Ballet company by the architect Jean-Loup Roubert. During 1994, restoration work began on the theatre. This consisted of modernizing the stage machinery and electrical facilities, while restoring and preserving the opulent décor, as well as strengthening the structure and foundation of the building. This restoration was completed in 2007.

Stamps

The French Post Office has issued two postage stamps on the building: The first was issued in September 1998, for the centenary of the death of Charles Garnier. It was designed by Claude Andréotto grouping elements which recall the artistic activities of the Opera Garnier: the profile of a dancer, a violin and a red curtain. The second, drawn and engraved by Martin Mörck, is issued in June 2006 and represents, in intaglio, the main facade.

Influence

The Palais Garnier inspired many other buildings over the following years.

- Teatro Massimo Bellini built from 1870 to 1890 in Catania, Sicily (Italy[61]

- The Amazon Theatre in Manaus (Brazil) built from 1884 to 1896. The overview is very similar, though the decoration is simpler.[62]

- The Thomas Jefferson Building, built from 1890 to 1897, of the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. is modelled after the Palais Garnier, most notably the facade and Great Hall.[63]

- The Opéra-Comique's Salle Favart, which opened in 1898, is an adaptation of Garnier's design on a smaller scale to fit a restricted site.[64]

- Several buildings in Poland were based on the design of the Palais Garnier. These include the Juliusz Słowacki Theatre in Kraków, built during 1893,[65] and also the Warsaw Philharmonic edifice in Warsaw, built between 1900 and 1901.[66]

- The Hanoi Opera House in Vietnam was built 1901–1911 during French Indochina colonial period based upon Palais Garnier. It is considered a representative French colonial architectural monument in Indochina.[67]

- The Theatro Municipal do Rio de Janeiro (1905–1909) was also modelled after Palais Garnier, particularly the Great Hall and stairs.[68]

- The Legends Hotel Chennai in India is inspired by the Palais Garnier, especially the Facade and statues.[69]

- The Façade of the Rialto Theatre, a former movie palace built in 1923–1924 and located in Montreal, Quebec, Canada, was designed after Palais Garnier.[70]

The Amazonas theatre in Manaus, Brazil (1884–1896)

The Amazonas theatre in Manaus, Brazil (1884–1896) The Thomas Jefferson Building at the Library of Congress (1890–1897)

The Thomas Jefferson Building at the Library of Congress (1890–1897) The former Warsaw Philharmonic Hall (1900–1901)

The former Warsaw Philharmonic Hall (1900–1901) National Opera House of Ukraine (opened 1901)

National Opera House of Ukraine (opened 1901) Municipal Theater of São Paulo (built 1903–1911)

Municipal Theater of São Paulo (built 1903–1911).jpg.webp) Hanoi Opera House (1901–1911)

Hanoi Opera House (1901–1911) Rialto Theatre in Montreal (1923–1924)

Rialto Theatre in Montreal (1923–1924)

See also

- Napoleon III style

- Bibliothèque-Musée de l'Opéra National de Paris

- Opéra National de Paris

- Paris Opera Ballet

- The works of Paul Dubois- French sculptor

- Salle Le Peletier

- The Phantom of the Opera

- Listing of the works of Alexandre Falguière

- List of works by Henri Chapu

- French opera

References

Citations

- Mead 1991, p. 146. Haussmann reported on 14 August 1871 that the site had been cleared and surveyed. A temporary building for the Opéra Agence was erected in August, and excavation was begun on the 27th.

- Mead 1991, p. 197. According to this source, more work was done after this date, and some parts of the building were never completed. The figure does not include the costs of acquiring and clearing the land, which was the responsibility of Haussmann's Service d'Architecture and probably exceeded 15 million francs (Mead 1991, pp. 140, 146).

- Beauvert 1996, p. 102.

- Hanser 2006, pp. 172–173.

- "Courrier de Paris", Le Monde illustré 22 January 1876, p. 50.

- Beauvert 1996, p. 108.

- Ayers 2004, p. 188.

- Hanser 2006, pp. 172–179.

- Simeone 2000, p. 177.

- Watkin 1996, pp. 391–392.

- Quoted and translated in Woolf 1988, pp. 220, 233. From Le Corbusier, Almanach d'Architecture Moderne, Collection de 'L'Esprit Nouveau, Charles Eliot Norton Lectures 1938–9 (Paris, 1955), p. 120 ("art de mensonge", "événement Garnier est un décor d'enterrement").

- "Bibliothèque-Musée de l'Opéra" (in French) at the BnF website. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- "Palais Garnier" Archived 18 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine at the Paris Opera website. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- Nuitter 1875, p. 250. Heights are measured from the ground level of the Place de l'Opéra. The sculpture at the apex of the stage flytower roof is not included, but would add an additional 7.50 metres.

- Nuitter 1875, pp. 249–250. The length is measured from the south side of the principal facade to the north side of the avant-corps of the administration; the widths, between the exteriors of the two lateral galleries, and the east and west pavilions; basement depth, from the ground level of the Place de l'Opéra to the bottom of the cistern under the stage house.

- Mead 1991, p. 156.

- Sarmant, Thierry, Histoire de Paris: Politique, Urbanisme, civilization, (2012), pg. 191

- Ducher, Robert, Caractéristique des Styles (1988), page 190

- Texier, Simon, Paris- Panorama de l'archirecture (2012) page 95

- Mead 1991, pp. 4–5; Sveiven, Megan (23 January 2011). "AD Classics: Paris Opera / Charles Garnier". ArchDaily. Retrieved 19 March 2015..

- Flannery, Rosemary (2012). Angels of Paris: An Architectural Tour Through the History of Paris. New York: The Little Bookroom. p. 173. ISBN 978-1-936941-01-8.

- Gjertson, Stephen (28 June 2010). "The Paris Opéra: Charles Garnier's Opulent Architectural Masterpiece". Stephen Gjertson Galleries.

Charles-Alphonse-Achille Gumery, Harmony, 1869. Gilded galvanoplastic bronze, height: 24' 7 1/4, west facade attic group.

- Jouffroy's group is titled l'Harmonie in Nuitter 1878, p. 11, and in Garnier 1875–81, vol. 1, p. 424, vol. 2, p. 273, but is identified as La Poésie in the "Table des planches" of the 1875 atlas folio Statues décoratives (View at Wikimedia Commons), and according to Fontaine 2000, p. 82, is also sometimes referred to as Lyric Poetry.

- Fontaine 2000

- Kirkland 2013, pp. 283—284.

- Fontaine 2004, p. 152.

- Fontaine 2004, p. 190.

- Paris Past & Present, Volume 2, 1902, p. 35

- Hanser 2006, p. 177.

- Fontaine 2004, p. 94–95.

- Garnier 1871, p. 205; quoted and translated by Charles Penwarden in Fontaine 2004, p. 94.

- Paris Opera Restaurant Press Release

- "Guillaume Tison-Malthé, aux fourneaux de L'Opéra Restaurant". cuisine.journaldesfemmes.com. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- Mead 1991, p. 53.

- Kirkland 2014, pp. 188–189.

- Mead 1991, pp. 53–56.

- Mead 1991, p. 58; Kirkland. Page 190.

- Kirkland 2013, pp. 185–186.

- Kirkland 2013, p. 191.

- Mead 1991, p. 60 ("170 projects"); Kirkland 2013, p. 192 ("171 designs").

- Mead 1991, pp. 60–62. Only five projects were awarded prizes, but two were the result of collaborations.

- Kirkland 2013, p. 192.

- Quoted and translated in Mead 1991, pp. 76, 290.

- Translated and quoted by Ayers 2004, pp. 172–174. The architectural styles mentioned by the empress were those which prevailed during the reigns of Louis XIV, XV, and XVI. For more information, see the sections on Baroque, Rococo, and Neoclassicism in French architecture.

- Ayers 2004, pp. 172–174.

- Photo by Louis-Emile Durandelle. Mead 1991, p. 138, reproduces a different print (fig. 187) of the same photograph (from the Bibliothèque nationale, see a copy at Commons) and identifies the three men. This particular print is from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, whose annotator dates it to ca. 1870. The elevation of the opera house shown in the background is quite similar to a design dated to the spring of 1862 by Mead 1991, p. 90 (see copy at Commons).

- Mead 1991, p. 137.

- Mead 1991, pp. 146–147.

- Mead 1991, p. 147; Hanser 2006, p. 174; Ayers 2004, p. 174.

- Mead 1991, pp. 149–151.

- Mead 1991, p. 303.

- Fontaine 2000, pp. 91–92.

- Mead 1991, p. 185.

- Levin, Alicia. "A documentary overview of musical theaters in Paris, 1830–1900" in Fauser (2009), p. 382.

- Mead 1991, pp. 142–143, 168–170.

- Mead 1991, pp. 143–145. 170–172.

- Mead 1991, pp. 145–146; Folli & Merello 2004, p. 116.

- Simeone 2000, pp. 177–180.

- Huebner 2003, p. 303.

- "Chronology". Opéra national de Paris. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- "Teatro Massimo Bellini", Comune de Catania website. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- Ramm, Benjamin (16 March 2017). "The beautiful theatre in the heart of the Amazon rainforest". BBC News. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- Scott & Lee 1993, pp. 142–145.

- Mead 1996.

- "The Juliusz Słowacki Theatre". Karnet. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- "Filharmonia Narodowa". Fryderyk Chopin Institute. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- Sterling, Richard (1 December 2011). DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Vietnam and Angkor Wat. Penguin. ISBN 9780756687403.

- "História". Theatro Municipal do Rio de Janeiro (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- "The Legends Chennai". Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- "Rialto Theatre National Historic Site of Canada, Parks Canada".

Sources

- Allison, John, editor (2003). Great Opera Houses of the World, supplement to Opera Magazine, London.

- Ayers, Andrew (2004). The Architecture of Paris. Stuttgart; London: Edition Axel Menges. ISBN 978-3-930698-96-7.

- Beauvert, Thierry (1996). Opera Houses of the World. New York: The Vendome Press. ISBN 978-0-86565-977-3.

- Ducher, Robert (1988), Caractéristique des Styles, Paris: Flammarion, ISBN 2-08-011539-1

- Fauser, Annegret, editor; Everist, Mark, editor (2009). Music, Theater, and Cultural Transfer. Paris, 1830–1914. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-23926-2.

- Folli, Andrea; Merello, Gisella (2004). "The Splendour of the Garnier Rooms at the Monte Carlo Casino", pp. 112–137, in Bonillo, Jean-Lucien, et al., Charles Garnier and Gustave Eiffel on the French and Italian Rivieras: The Dream of Reason (in English and French). Marseilles: Editions Imbernon. ISBN 9782951639614.

- Fontaine, Gérard (2000). Charles Garnier's Opéra: Architecture and Exterior Decor, translated by Ellie Rea and Barbara Shapiro-Comte. Paris: Éditions du Patrimoine. ISBN 978-2-85822-581-1.

- Fontaine, Gérard (2004). Charles Garnier's Opéra: Architecture and Interior Decor, translated by Charles Penwarden. Paris: Éditions du Patrimoine. ISBN 978-2-85822-801-0.

- Garnier, Charles (1871). Le Théâtre. Paris: Hachette. View at Google Books.

- Garnier, Charles (1875–81). Le nouvel Opéra de Paris, two volumes text and six atlas folios (two with architectural plates and four with plates of photographs by Louis-Emile Durandelle of sculptures and paintings). Paris: Ducher. List of entries at WorldCat.

- Vol. 1, text (1878). 522 pages. View at Google Books.

- Vol. 1, plates (1880). Partie architecturale, 40 plates. OCLC 487188010, 180042214.

- Vol. 2, text (1881). 425 pages. View at Google Books.

- Vol. 2, plates (1880). Partie architecturale, 60 plates. OCLC 487187971, 180042222.

- [Vol. 3] (1875). Sculpture ornamentale, 45 plates. OCLC 487188045.

- [Vol. 4] (1875). Statues décoratives, 35 plates. OCLC 487188137. View at Wikimedia Commons.

- [Vol. 5] (1875). Peintures décoratives, 20 plates. OCLC 487188071.

- [Vol. 6] (1875). Bronzes, 15 plates. OCLC 487188105.

- Hanser, David A. (2006). Architecture of France. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-31902-0.

- Huebner, Steven (2003). "After 1850 at the Paris Opéra: institution and repertory", pp. 291–317 in The Cambridge Companion to Grand Opera, edited by David Charlton. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64118-0. ISBN 978-0-521-64683-3 (paperback).

- Guest, Ivor Forbes (1974). Ballet of the Second Empire. London: Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 978-0-273-00496-7.

- Guest, Ivor Forbes (2006). The Paris Opera Ballet. London: Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 978-1-85273-109-0.

- Kirkland, Stephane (2013). Paris Reborn: Napoléon III, Baron Haussmann, and the Quest to Build a Modern City. New York: St Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-62689-1.

- Kleiner, Fred S. (2006). Gardner's Art Through The Ages. Belmont, California: Thomsom Wadsworth. ISBN 978-0-534-63640-1.

- Mead, Christopher Curtis (1991). Charles Garnier's Paris Opéra: Architectural Empathy and the Renaissance of French Classicism. New York: The Architectural History Foundation. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-13275-6.

- Mead, Christopher Curtis (1996). "Bernier, Stanislas-Louis", vol. 3, pp. 826–827, in The Dictionary of Art, edited by Jane Turner. London: Macmillan. ISBN 9781884446009. Also at Oxford Art Online (subscription required).

- Nuitter, Charles (1875). Le nouvel Opéra (with 59 engravings). Paris: Hachette. Copies 1, 2, and 3 at Google Books.

- Nuitter, Charles (1878). Histoire et description du nouvel Opéra. Paris: Plon. View at Gallica. (Title page undated; signed by Nuitter and dated 28 November 1878 on p. 42; Gallica gives the date of publication as 1883.)

- Savorra, Massimiliano (2010). "Una lezione da Parigi al mondo. Il teatro di Charles Garnier", in "Architettura dell’Eclettismo. Il teatro dell’Ottocento e del primo Novecento. Architettura, tecniche teatrali e pubblico",edited by L. Mozzoni, S. Santini. Napoli: Liguori, pp. 61–133 ISBN 978-88-207-4984-2.

- Scott, Pamela; Lee, Antoinette J. (1993). Buildings of the District of Columbia. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-506146-8.

- Simeone, Nigel (2000). Paris: A Musical Gazetteer. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08053-7.

- Sterling, Richard (2011). Vietnam & Angor Wat (DK Eyewitness Travel Guide). London: DK Publishing. ISBN 9780756687403.

- Texier, Simon (2012). Paris- Panorama de l'architecture. Parigramme. ISBN 978-2-84096-667-8.

- Watkin, David (1996). A History of Western Architecture, 2nd edition. New York: Barnes & Noble Books. ISBN 978-0-7607-0252-9.

- Woolf, Penelope (1988). "Symbol of the Second Empire: cultural politics and the Paris Opera House", pp. 214–235, in ''The Iconography of Landscape, edited by Denis Cosgrove and Stephen Daniels. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521389150.

- Zeitz, Karyl Lynn (1991). Opera: the Guide to Western Europe's Great Houses. Santa Fe, New Mexico: John Muir Publications. ISBN 978-0-945465-81-2.

External links

| External video | |

|---|---|

- Official website

(in French)

(in French) - L'Opéra Restaurant (in English)

- History of architecture (in Spanish)

- Unused architectural drawings for the Opéra de Paris by Charles Rohault de Fleury

- 360° Panoramas of the Paris Opera by the Media Center for Art History at Columbia University

- Selected images and video of the Palais Garnier by Art Days