Pali

Pali (/ˈpɑːli/) is a Middle Indo-Aryan liturgical language native to the Indian subcontinent. It is widely studied because it is the language of the Buddhist Pāli Canon or Tipiṭaka as well as the sacred language of Theravāda Buddhism.[2] Early in the language's history, it was written in the Brahmi script.

| Pali | |

|---|---|

| |

| Pronunciation | [paːli] |

| Native to | Indian subcontinent |

| Era | 3rd century BCE – present[1] Liturgical language of Theravada Buddhism |

Indo-European

| |

| Brāhmī, Kharosthi, Khmer, Mon-Burmese, Thai, Sinhala and transliteration to the Latin alphabet | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | pi |

| ISO 639-2 | pli |

| ISO 639-3 | pli |

Linguist List | pli |

| Glottolog | pali1273 |

Origin and development

Etymology

The word 'Pali' is used as a name for the language of the Theravada canon. The word seems to have its origins in commentarial traditions, wherein the Pāli (in the sense of the line of original text quoted) was distinguished from the commentary or vernacular translation that followed it in the manuscript.[3] K. R. Norman suggests that its emergence was based on a misunderstanding of the compound pāli-bhāsa, with pāli being interpreted as the name of a particular language.[3]: 1

The name Pali does not appear in the canonical literature, and in commentary literature is sometimes substituted with tanti, meaning a string or lineage.[3]: 1 This name seems to have emerged in Sri Lanka early in the second millennium CE during a resurgence in the use of Pali as a courtly and literary language.[4][3]: 1

As such, the name of the language has caused some debate among scholars of all ages; the spelling of the name also varies, being found with both long "ā" [ɑː] and short "a" [a], and also with either a retroflex [ɭ] or non-retroflex [l] "l" sound. Both the long ā and retroflex ḷ are seen in the ISO 15919/ALA-LC rendering, Pāḷi; however, to this day there is no single, standard spelling of the term, and all four possible spellings can be found in textbooks. R. C. Childers translates the word as "series" and states that the language "bears the epithet in consequence of the perfection of its grammatical structure".[5]

Geographic origin

There is persistent confusion as to the relation of Pāḷi to the vernacular spoken in the ancient kingdom of Magadha, which was located around modern-day Bihār. Beginning in the Theravada commentaries, Pali was identified with 'Magahi', the language of the kingdom of Magadha, and this was taken to also be the language that the Buddha used during his life.[3] In the 19th century, the British Orientalist Robert Caesar Childers argued that the true or geographical name of the Pali language was Magadhi Prakrit, and that because pāḷi means "line, row, series", the early Buddhists extended the meaning of the term to mean "a series of books", so pāḷibhāsā means "language of the texts".[6]

However, modern scholarship has regarded Pali as a mix of several Prakrit languages from around the 3rd century BCE, combined and partially Sanskritized.[7] There is no attested dialect of Middle Indo-Aryan with all the features of Pali.[3]: 5 In the modern era, it has been possible to compare Pali with inscriptions known to be in Magadhi Prakrit, as well as other texts and grammars of that language.[3] While none of the existing sources specifically document pre-Ashokan Magadhi, the available sources suggest that Pali is not equatable with that language.[3]

Modern scholars generally regard Pali to have originated from a western dialect, rather than an eastern one.[8] Pali has some commonalities with both the western Ashokan Edicts at Girnar in Saurashtra, and the Central-Western Prakrit found in the eastern Hathigumpha inscription.[3]: 5 These similarities lead scholars to associate Pali with this region of western India.[9] Nonetheless, Pali does retain some eastern features that have been referred to as Māgadhisms.[10]

Pāḷi, as a Middle Indo-Aryan language, is different from Classical Sanskrit more with regard to its dialectal base than the time of its origin. A number of its morphological and lexical features show that it is not a direct continuation of Ṛgvedic Sanskrit. Instead it descends from one or more dialects that were, despite many similarities, different from Ṛgvedic.[11]

Early history

The Theravada commentaries refer to the Pali language as "Magadhan" or the "language of Magadha".[3]: 2 This identification first appears in the commentaries, and may have been an attempt by Buddhists to associate themselves more closely with the Maurya Empire.[3]

However, only some of the Buddha's teachings were delivered in the historical territory of Magadha kingdom.[3] Scholars consider it likely that he taught in several closely related dialects of Middle Indo-Aryan, which had a high degree of mutual intelligibility.

Theravada tradition, as recorded in chronicles like the Mahavamsa, states that the Tipitaka was first committed to writing during the first century BCE.[3]: 5 This move away from the previous tradition of oral preservation is described as being motivated by threats to the Sangha from famine, war, and the growing influence of the rival tradition of the Abhayagiri Vihara.[3]: 5 This account is generally accepted by scholars, though there are indications that Pali had already begun to be recorded in writing by this date.[3]: 5 By this point in its history, scholars consider it likely that Pali had already undergone some initial assimilation with Sanskrit, such as the conversion of the Middle-Indic bamhana to the more familiar Sanskrit brāhmana that contemporary brahmans used to identify themselves.[3]: 6

In Sri Lanka, Pali is thought to have entered into a period of decline ending around the 4th or 5th century (as Sanskrit rose in prominence, and simultaneously, as Buddhism's adherents became a smaller portion of the subcontinent), but ultimately survived. The work of Buddhaghosa was largely responsible for its reemergence as an important scholarly language in Buddhist thought. The Visuddhimagga, and the other commentaries that Buddhaghosa compiled, codified and condensed the Sinhala commentarial tradition that had been preserved and expanded in Sri Lanka since the 3rd century BCE.

With only a few possible exceptions, the entire corpus of Pali texts known today is believed to derive from the Anuradhapura Maha Viharaya in Sri Lanka.[8] While literary evidence exists of Theravadins in mainland India surviving into the 13th Century, no Pali texts specifically attributable to this tradition have been recovered.[8] Some texts (such as the Milindapanha) may have been composed in India before being transmitted to Sri Lanka, but the surviving versions of the texts are those preserved by the Mahavihara in Ceylon and shared with monasteries in Theravada Southeast Asia.[8]

The earliest inscriptions in Pali found in mainland Southeast Asia are from the first millennium CE, some possibly dating to as early as the 4th Century.[8] Inscriptions are found in what are now Burma, Laos, Thailand and Cambodia and may have spread from southern India rather than Sri Lanka.[8] By the 11th Century, a so-called "Pali renaissance" began in the vicinity of Pagan, gradually spreading to the rest of mainland Southeast Asia as royal dynasties sponsored monastic lineages derived from the Mahavihara of Anuradhapura.[8] This era was also characterized by the adoption of Sanskrit conventions and poetic forms (such as kavya) that had not been features of earlier Pali literature.[12] This process began as early as the 5th Century, but intensified early in the second millennium as Pali texts on poetics and composition modeled on Sanskrit forms began to grow in popularity.[12] One milestone of this period was the publication of the Subodhalankara during the 14th Century, a work attributed to Sangharakkhita Mahāsāmi and modeled on the Sanskrit Kavyadarsa.[12]

Despite an expansion of the number and influence of Mahavihara-derived monastics, this resurgence of Pali study resulted in no production of any new surviving literary works in Pali.[8] During this era, correspondences between royal courts in Sri Lanka and mainland Southeast Asia were conducted in Pali, and grammars aimed at speakers of Sinhala, Burmese, and other languages were produced.[4] The emergence of the term 'Pali' as the name of the language of the Theravada canon also occurred during this era.[4]

Manuscripts and inscriptions

While Pali is generally recognized as an ancient language, no epigraphical or manuscript evidence has survived from the earliest eras.[13][14] The earliest samples of Pali discovered are inscriptions believed to date from 5th to 8th Century located in mainland Southeast Asia, specifically central Siam and lower Burma.[14] These inscriptions typically consist of short excerpts from the Pali Canon and non-canonical texts, and include several examples of the Ye dhamma hetu verse.[14]

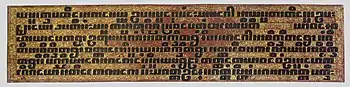

Surprisingly, the oldest surviving Pali manuscript was discovered in Nepal dating to the 9th Century.[14] It is in the form of four palm-leaf folios, using a transitional script deriving from the Gupta script to scribe a fragment of the Cullavagga.[15] The oldest known manuscripts from Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia date to the 13th-15th Century, with few surviving examples.[14][16] Very few manuscripts older than 400 years have survived, and complete manuscripts of the four Nikayas are only available in examples from the 17th Century and later.[13]

Early Western research

Pali was first mentioned in Western literature in Simon de la Loubère's descriptions of his travels in the kingdom of Siam.[3] An early grammar and dictionary was published by Methodist missionary Benjamin Clough in 1824, and an initial study published by Eugène Burnouf and Christian Lassen in 1826 (Essai Sur Le Pali, Ou Langue Sacree de La Presqu'ile Au-Dela Du Gange).[3] The first modern Pali-English dictionary was published by Robert Childers in 1872 and 1875.[17] Following the foundation of the Pali Text Society, English Pali studies grew rapidly and Childer's dictionary became outdated.[17] Planning for a new dictionary began in the early 1900s, but delays (including the outbreak of World War I) meant that work was not completed until 1925.[17]

T. W. Rhys Davids in his book Buddhist India,[18] and Wilhelm Geiger in his book Pāli Literature and Language, suggested that Pali may have originated as a lingua franca or common language of culture among people who used differing dialects in North India, used at the time of the Buddha and employed by him. Another scholar states that at that time it was "a refined and elegant vernacular of all Aryan-speaking people".[19] Modern scholarship has not arrived at a consensus on the issue; there are a variety of conflicting theories with supporters and detractors.[20] After the death of the Buddha, Pali may have evolved among Buddhists out of the language of the Buddha as a new artificial language.[21] R. C. Childers, who held to the theory that Pali was Old Magadhi, wrote: "Had Gautama never preached, it is unlikely that Magadhese would have been distinguished from the many other vernaculars of Hindustan, except perhaps by an inherent grace and strength which make it a sort of Tuscan among the Prakrits."[22]

Modern scholarship

According to K. R. Norman, differences between different texts within the canon suggest that it contains material from more than a single dialect.[3]: 2 He also suggests it is likely that the viharas in North India had separate collections of material, preserved in the local dialect.[3]: 4 In the early period it is likely that no degree of translation was necessary in communicating this material to other areas. Around the time of Ashoka there had been more linguistic divergence, and an attempt was made to assemble all the material.[3]: 4 It is possible that a language quite close to the Pali of the canon emerged as a result of this process as a compromise of the various dialects in which the earliest material had been preserved, and this language functioned as a lingua franca among Eastern Buddhists from then on.[3]: 5 Following this period, the language underwent a small degree of Sanskritisation (i.e., MIA bamhana > brahmana, tta > tva in some cases).[23]

Bhikkhu Bodhi, summarizing the current state of scholarship, states that the language is "closely related to the language (or, more likely, the various regional dialects) that the Buddha himself spoke". He goes on to write:

Scholars regard this language as a hybrid showing features of several Prakrit dialects used around the third century BCE, subjected to a partial process of Sanskritization. While the language is not identical to what Buddha himself would have spoken, it belongs to the same broad language family as those he might have used and originates from the same conceptual matrix. This language thus reflects the thought-world that the Buddha inherited from the wider Indian culture into which he was born, so that its words capture the subtle nuances of that thought-world.

— Bhikkhu Bodhi[7]

According to A. K. Warder, the Pali language is a Prakrit language used in a region of Western India.[24] Warder associates Pali with the Indian realm (janapada) of Avanti, where the Sthavira nikāya was centered.[24] Following the initial split in the Buddhist community, the Sthavira nikāya became influential in Western and South India while the Mahāsāṃghika branch became influential in Central and East India.[9] Akira Hirakawa and Paul Groner also associate Pali with Western India and the Sthavira nikāya, citing the Saurashtran inscriptions, which are linguistically closest to the Pali language.[9]

Emic views of Pali

Although Sanskrit was said in the Brahmanical tradition to be the unchanging language spoken by the gods in which each word had an inherent significance, such views for any language was not shared in the early Buddhist traditions, in which words were only conventional and mutable signs.[25] This view of language naturally extended to Pali and may have contributed to its usage (as an approximation or standardization of local Middle Indic dialects) in place of Sanskrit. However, by the time of the compilation of the Pali commentaries (4th or 5th century), Pali was described by the anonymous authors as the natural language, the root language of all beings.[26][3]: 2

Comparable to Ancient Egyptian, Latin or Hebrew in the mystic traditions of the West, Pali recitations were often thought to have a supernatural power (which could be attributed to their meaning, the character of the reciter, or the qualities of the language itself), and in the early strata of Buddhist literature we can already see Pali dhāraṇīs used as charms, as, for example, against the bite of snakes. Many people in Theravada cultures still believe that taking a vow in Pali has a special significance, and, as one example of the supernatural power assigned to chanting in the language, the recitation of the vows of Aṅgulimāla are believed to alleviate the pain of childbirth in Sri Lanka. In Thailand, the chanting of a portion of the Abhidhammapiṭaka is believed to be beneficial to the recently departed, and this ceremony routinely occupies as much as seven working days. There is nothing in the latter text that relates to this subject, and the origins of the custom are unclear.[27]

Pali today

Pali died out as a literary language in mainland India in the fourteenth century but survived elsewhere until the eighteenth.[28] Today Pali is studied mainly to gain access to Buddhist scriptures, and is frequently chanted in a ritual context. The secular literature of Pali historical chronicles, medical texts, and inscriptions is also of great historical importance. The great centres of Pali learning remain in Sri Lanka and other Theravada nations of Southeast Asia: Myanmar, Thailand, Laos and Cambodia. Since the 19th century, various societies for the revival of Pali studies in India have promoted awareness of the language and its literature, including the Maha Bodhi Society founded by Anagarika Dhammapala.

In Europe, the Pali Text Society has been a major force in promoting the study of Pali by Western scholars since its founding in 1881. Based in the United Kingdom, the society publishes romanized Pali editions, along with many English translations of these sources. In 1869, the first Pali Dictionary was published using the research of Robert Caesar Childers, one of the founding members of the Pali Text Society. It was the first Pali translated text in English and was published in 1872. Childers' dictionary later received the Volney Prize in 1876.

The Pali Text Society was founded in part to compensate for the very low level of funds allocated to Indology in late 19th-century England and the rest of the UK; incongruously, the citizens of the UK were not nearly so robust in Sanskrit and Prakrit language studies as Germany, Russia, and even Denmark. Even without the inspiration of colonial holdings such as the former British occupation of Sri Lanka and Burma, institutions such as the Danish Royal Library have built up major collections of Pali manuscripts, and major traditions of Pali studies.

Pali literature

Pali literature is usually divided into canonical and non-canonical or extra-canonical texts.[29] Canonical texts include the whole of the Pali Canon or Tipitaka. With the exception of three books placed in the Khuddaka Nikaya by only the Burmese tradition, these texts (consisting of the five Nikayas of the Sutta Pitaka, the Vinaya Pitaka, and the books of the Abhidhamma Pitaka) are traditionally accepted as containing the words of the Buddha and his immediate disciples by the Theravada tradition.

Extra-canonical texts can be divided into several categories:

- Commentaries (Atthakatha) which record additional details and explanations regarding the contents of the Suttas.

- Sub-commentaries (ṭīkā) which explain and add contents to the commentaries

- Chronicles (Vaṃsa) which relate the history of Buddhism in Sri Lanka, as well as the origins of famous relics and shrines and the deeds of historical and mythical kings

- Manuals and treatises, which include summaries of canonical books and compendia of teachings and techniques like the Visuddhimagga

- Abhidhamma manuals, which explain the contents of the Abhidhamma Pitaka

Other types of texts present in Pali literature include works on grammar and poetics, medical texts, astrological and divination texts, cosmologies, and anthologies or collections of material from the canonical literature.[3]

While the majority of works in Pali are believed to have originated with the Sri Lankan tradition and then spread to other Theravada regions, some texts may have other origins. The Milinda Panha may have originated in northern India before being translated from Sanskrit or Gandhari Prakrit.[30] There are also a number of texts that are believed to have been composed in Pali in Sri Lanka, Thailand and Burma but were not widely circulated. This regional Pali literature is currently relatively little known, particularly in the Thai tradition, with many manuscripts never catalogued or published.[14]

Relationship to other languages

Paiśācī

Paiśācī is a largely unattested literary language of classical India that is mentioned in Prakrit and Sanskrit grammars of antiquity. It is found grouped with the Prakrit languages, with which it shares some linguistic similarities, but was not considered a spoken language by the early grammarians because it was understood to have been purely a literary language.[31]

In works of Sanskrit poetics such as Daṇḍin's Kavyadarsha, it is also known by the name of Bhūtabhāṣā, an epithet which can be interpreted as 'dead language' (i.e., with no surviving speakers), or bhūta means past and bhāṣā means language i.e. 'a language spoken in the past'. Evidence which lends support to this interpretation is that literature in Paiśācī is fragmentary and extremely rare but may once have been common.

The 13th-century Tibetan historian Buton Rinchen Drub wrote that the early Buddhist schools were separated by choice of sacred language: the Mahāsāṃghikas used Prākrit, the Sarvāstivādins used Sanskrit, the Sthaviravādins used Paiśācī, and the Saṃmitīya used Apabhraṃśa.[32] This observation has led some scholars to theorize connections between Pali and Paiśācī; Sten Konow concluded that it may have been an Indo-Aryan language spoken by Dravidian people in South India, and Alfred Master noted a number of similarities between surviving fragments and Pali morphology.[31][33]

Ardha-Magadhi Prakrit

Ardhamagadhi Prakrit was a Middle Indo-Aryan language and a Dramatic Prakrit thought to have been spoken in modern-day Bihar & Eastern Uttar Pradesh and used in some early Buddhist and Jain drama. It was originally thought to be a predecessor of the vernacular Magadhi Prakrit, hence the name (literally "half-Magadhi"). Ardhamāgadhī was prominently used by Jain scholars and is preserved in the Jain Agamas.[34]

Ardhamagadhi Prakrit differs from later Magadhi Prakrit in similar ways to Pali, and was often believed to be connected with Pali on the basis of the belief that Pali recorded the speech of the Buddha in an early Magadhi dialect.

Magadhi Prakrit

Magadhi Prakrit was a Middle Indic language spoken in present-day Bihar, and eastern Uttar Pradesh. Its use later expanded southeast to include some regions of modern-day Bengal, Odisha, and Assam, and it was used in some Prakrit dramas to represent vernacular dialogue. Preserved examples of Magadhi Prakrit are from several centuries after the theorized lifetime of the Buddha, and include inscriptions attributed to Asoka Maurya.[35]

Differences observed between preserved examples of Magadhi Prakrit and Pali lead scholars to conclude that Pali represented a development of a northwestern dialect of Middle Indic, rather than being a continuation of a language spoken in the area of Magadha in the time of the Buddha.

Lexicon

Nearly every word in Pāḷi has cognates in the other Middle Indo-Aryan languages, the Prakrits. The relationship to Vedic Sanskrit is less direct and more complicated; the Prakrits were descended from Old Indo-Aryan vernaculars. Historically, influence between Pali and Sanskrit has been felt in both directions. The Pali language's resemblance to Sanskrit is often exaggerated by comparing it to later Sanskrit compositions—which were written centuries after Sanskrit ceased to be a living language, and are influenced by developments in Middle Indic, including the direct borrowing of a portion of the Middle Indic lexicon; whereas, a good deal of later Pali technical terminology has been borrowed from the vocabulary of equivalent disciplines in Sanskrit, either directly or with certain phonological adaptations.

Post-canonical Pali also possesses a few loan-words from local languages where Pali was used (e.g. Sri Lankans adding Sinhala words to Pali). These usages differentiate the Pali found in the Suttapiṭaka from later compositions such as the Pali commentaries on the canon and folklore (e.g., commentaries on the Jataka tales), and comparative study (and dating) of texts on the basis of such loan-words is now a specialized field unto itself.

Pali was not exclusively used to convey the teachings of the Buddha, as can be deduced from the existence of a number of secular texts, such as books of medical science/instruction, in Pali. However, scholarly interest in the language has been focused upon religious and philosophical literature, because of the unique window it opens on one phase in the development of Buddhism.

Phonology

Vowels

| Height | Backness | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Front | Central | Back | ||

| High | i ⟨i⟩ iː ⟨ī⟩ |

u ⟨u⟩ uː ⟨ū⟩ | ||

| Mid | e, eː ⟨e⟩ | ɐ ⟨a⟩ | o, oː ⟨o⟩ | |

| Low | aː ⟨ā⟩ | |||

Vowels may be divided into

-

- pure vowels: a, ā

- sonant vowels: i, ī, u, ū

- diphthongs: e, o[36]

-

- vowels short by nature: a, i, u

- vowels long by nature: ā, ī, ū

- vowels of variable length: e, o[36]

Long and short vowels are only contrastive in open syllables; in closed syllables, all vowels are always short. Short and long e and o are in complementary distribution: the short variants occur only in closed syllables, the long variants occur only in open syllables. Short and long e and o are therefore not distinct phonemes.

vowels e and o are long in an open syllable:

at the end of a syllable as in [ne-tum̩] เนตุํ 'to lead'

at the end of a syllable as in [so-tum̩] โสตุํ 'to hear'[36]

vowels are short in a closed syllable:

when followed by a consonant with which they make a syllable as in [upek-khā] 'indifference', [sot-thi] 'safety'[36]

For vowels ā, ī, ū, e appears for a before double-consonance:

- seyyā = sayyā 'bed'

- pheggu = phaigu 'empty, worthless'[37]

The vowels ⟨i⟩ and ⟨u⟩ are lengthened in the flexional endings including: -īhi, -ūhi and -īsu[37]

A sound called anusvāra (Skt.; Pali: niggahīta), represented by the letter ṁ (ISO 15919) or ṃ (ALA-LC) in romanization, and by a raised dot in most traditional alphabets, originally marked the fact that the preceding vowel was nasalized. That is, aṁ, iṁ and uṁ represented [ã], [ĩ] and [ũ]. In many traditional pronunciations, however, the anusvāra is pronounced more strongly, like the velar nasal [ŋ], so that these sounds are pronounced instead [ãŋ], [ĩŋ] and [ũŋ]. However pronounced, ṁ never follows a long vowel; ā, ī and ū are converted to the corresponding short vowels when ṁ is added to a stem ending in a long vowel, e.g. kathā + ṁ becomes kathaṁ, not *kathāṁ, devī + ṁ becomes deviṁ, not *devīṁ.

Changes of vowels due to the structure of the word

Final vowels

The final consonants of the Sanskrit words have been dropped in Pali and thus all the words end in a vowel or in a nasal vowel: kāntāt -> kantā 'from the loved one'; kāntāṃ -> kantaṃ 'the loved one'

The final vowels were usually weak in pronunciation and hence they were shortened: akārsit -> akāsi 'he did'.[36]

Consonants

| Labial | Dental/ alveolar |

Retroflex | Post-alveolar/ Palatal |

Velar | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop | Nasal | m ⟨m⟩ | n ⟨n⟩ | ɳ ⟨ṇ⟩ | ɲ ⟨ñ⟩ | (ŋ ⟨ṅ⟩) | ||

| voiceless | unaspirated | p ⟨p⟩ | t ⟨t⟩ | ʈ ⟨ṭ⟩ | tʃ ⟨c⟩ | k ⟨k⟩ | ||

| aspirated | pʰ ⟨ph⟩ | tʰ ⟨th⟩ | ʈʰ ⟨ṭh⟩ | tʃʰ ⟨ch⟩ | kʰ ⟨kh⟩ | |||

| voiced | unaspirated | b ⟨b⟩ | d ⟨d⟩ | ɖ ⟨ḍ⟩ | dʒ ⟨j⟩ | ɡ ⟨g⟩ | ||

| aspirated | bʱ ⟨bh⟩ | dʱ ⟨dh⟩ | ɖʱ ⟨ḍh⟩ | dʒʱ ⟨jh⟩ | ɡʱ ⟨gh⟩ | |||

| Fricative | s ⟨s⟩ | h ⟨h⟩ | ||||||

| Approximant | central | ʋ ⟨v⟩ | ɻ ⟨r⟩ | j ⟨y⟩ | ||||

| lateral | l ⟨l⟩ | (ɭ ⟨ḷ⟩) | ||||||

| lateral aspirated | (ɭʱ ⟨ḷh⟩) | |||||||

Among the labial consonants, [ʋ] is labiodental and the rest is bilabial. Among the dental/alveolar consonants, the majority is dental but [s] and [l] are alveolar.

Of the sounds listed above only the three consonants in parentheses, ṅ, ḷ, and ḷh, are not distinct phonemes in Pali: ṅ only occurs before velar stops, while ḷ and ḷh are allophones of single ḍ and ḍh occurring between vowels.

In Pali language, the consonants may be divided according to their strength or power of resistance. The strength decreases in the order of: mutes, sibilant, nasals, l, v, y, r

When two consonants come together, they are subject to one of the following change:

- they are assimilated to each other

- they are first adapted and then assimilated to each other

- they give rise to a new consonant group

- they separated by the insertion of a vowel infix

- they are sometimes interchanged by metathesis[38]

Aspirate consonants

when one of the two consonants is the sibilant s, then the new group of consonants has the aspiration in the last consonant: as-ti (root: √as) > atthi 'is'

the sibilant s, followed by a nasal, is changed to h and then it is transposed after the nasal (metathesis): akas-ma > akah-ma > akamha 'we did'[38]

Alternation between y and v

Pali v appears for Skr. y. For instance, āvudha -> āyudha 'weapon'; kasāva -> kasāya 'dirt, sin'. After the svarabhakti-vowel I there appear v instead of y as in praṭyamsa -> pativimsa.[37]

Alternation between r and l

Representation of r by l is very common in Pali, and in Pkr. it is the rule for Magadhi, although this substitution occurs sporadically also in other dialect. This, initially, in lūjjati -> rūjyate 'falls apart'; sometimes double forms with l and r occur in Skr.: lūkha -> lūksa, rūksa 'gross, bad'[37]

Morphology

Pali is a highly inflected language, in which almost every word contains, besides the root conveying the basic meaning, one or more affixes (usually suffixes) which modify the meaning in some way. Nouns are inflected for gender, number, and case; verbal inflections convey information about person, number, tense and mood.

Nominal inflection

Pali nouns inflect for three grammatical genders (masculine, feminine, and neuter) and two numbers (singular and plural). The nouns also, in principle, display eight cases: nominative or paccatta case, vocative, accusative or upayoga case, instrumental or karaṇa case, dative or sampadāna case, ablative, genitive or sāmin case, and locative or bhumma case; however, in many instances, two or more of these cases are identical in form; this is especially true of the genitive and dative cases.

a-stems

a-stems, whose uninflected stem ends in short a (/ə/), are either masculine or neuter. The masculine and neuter forms differ only in the nominative, vocative, and accusative cases.

| Masculine (loka- "world") | Neuter (yāna- "carriage") | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| Nominative | loko | lokā | yānaṁ | yānāni |

| Vocative | loka | |||

| Accusative | lokaṁ | loke | ||

| Instrumental | lokena | lokehi | yānena | yānehi |

| Ablative | lokā (lokamhā, lokasmā; lokato) | yānā (yānamhā, yānasmā; yānato) | ||

| Dative | lokassa (lokāya) | lokānaṁ | yānassa (yānāya) | yānānaṁ |

| Genitive | lokassa | yānassa | ||

| Locative | loke (lokasmiṁ) | lokesu | yāne (yānasmiṁ) | yānesu |

ā-stems

Nouns ending in ā (/aː/) are almost always feminine.

| Feminine (kathā- "story") | ||

|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | |

| Nominative | kathā | kathāyo |

| Vocative | kathe | |

| Accusative | kathaṁ | |

| Instrumental | kathāya | kathāhi |

| Ablative | ||

| Dative | kathānaṁ | |

| Genitive | ||

| Locative | kathāya, kathāyaṁ | kathāsu |

i-stems and u-stems

i-stems and u-stems are either masculine or neuter. The masculine and neuter forms differ only in the nominative and accusative cases. The vocative has the same form as the nominative.

| Masculine (isi- "seer") | Neuter (akkhi- "eye") | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| Nominative | isi | isayo, isī | akkhi, akkhiṁ | akkhī, akkhīni |

| Vocative | ||||

| Accusative | isiṁ | |||

| Instrumental | isinā | isihi, isīhi | akkhinā | akkhihi, akkhīhi |

| Ablative | isinā, isito | akkhinā, akkhito | ||

| Dative | isino | isinaṁ, isīnaṁ | akkhino | akkhinaṁ, akkhīnaṁ |

| Genitive | isissa, isino | akkhissa, akkhino | ||

| Locative | isismiṁ | isisu, isīsu | akkhismiṁ | akkhisu, akkhīsu |

| Masculine (bhikkhu- "monk") | Neuter (cakkhu- "eye") | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| Nominative | bhikkhu | bhikkhavo, bhikkhū | cakkhu, cakkhuṁ | cakkhūni |

| Vocative | ||||

| Accusative | bhikkhuṁ | |||

| Instrumental | bhikkhunā | bhikkhūhi | cakkhunā | cakkhūhi |

| Ablative | ||||

| Dative | bhikkhuno | bhikkhūnaṁ | cakkhuno | cakkhūnaṁ |

| Genitive | bhikkhussa, bhikkhuno | bhikkhūnaṁ, bhikkhunnaṁ | cakkhussa, cakkhuno | cakkhūnaṁ, cakkhunnaṁ |

| Locative | bhikkhusmiṁ | bhikkhūsu | cakkhusmiṁ | cakkhūsu |

Linguistic analysis of a Pali text

From the opening of the Dhammapada:

Mano-pubbaṅ-gam-ā

Mind-before-going-M.PL.NOM

dhamm-ā,

dharma-M.PL.NOM,

mano-seṭṭh-ā

mind-foremost-M.PL.NOM

mano-may-ā;

mind-made-M.PL.NOM

Manas-ā=ce

Mind-N.SG.INST=if

paduṭṭh-ena,

corrupted-N.SG.INST

bhāsa-ti=vā

speak-3.SG.PRES=either

karo-ti=vā,

act-3.SG.PRES=or,

Ta-to

That-from

naṁ

him

dukkhaṁ

suffering

anv-e-ti,

after-go-3.SG.PRES,

cakkaṁ

wheel

'va

as

vahat-o

carrying(beast)-M.SG.GEN

pad-aṁ.

foot-N.SG.ACC

The three compounds in the first line literally mean:

- manopubbaṅgama "whose precursor is mind", "having mind as a fore-goer or leader"

- manoseṭṭha "whose foremost member is mind", "having mind as chief"

- manomaya "consisting of mind" or "made by mind"

The literal meaning is therefore: "The dharmas have mind as their leader, mind as their chief, are made of/by mind. If [someone] either speaks or acts with a corrupted mind, from that [cause] suffering goes after him, as the wheel [of a cart follows] the foot of a draught animal."

A slightly freer translation by Acharya Buddharakkhita

- Mind precedes all mental states. Mind is their chief; they are all mind-wrought.

- If with an impure mind a person speaks or acts suffering follows him

- like the wheel that follows the foot of the ox.

Conversion between Sanskrit and Pali forms

Pali and Sanskrit are very closely related and the common characteristics of Pali and Sanskrit were always easily recognized by those in India who were familiar with both. A large part of Pali and Sanskrit word-stems are identical in form, differing only in details of inflection.

Technical terms from Sanskrit were converted into Pali by a set of conventional phonological transformations. These transformations mimicked a subset of the phonological developments that had occurred in Proto-Pali. Because of the prevalence of these transformations, it is not always possible to tell whether a given Pali word is a part of the old Prakrit lexicon, or a transformed borrowing from Sanskrit. The existence of a Sanskrit word regularly corresponding to a Pali word is not always secure evidence of the Pali etymology, since, in some cases, artificial Sanskrit words were created by back-formation from Prakrit words.

The following phonological processes are not intended as an exhaustive description of the historical changes which produced Pali from its Old Indic ancestor, but rather are a summary of the most common phonological equations between Sanskrit and Pali, with no claim to completeness.

Vowels and diphthongs

- Sanskrit ai and au always monophthongize to Pali e and o, respectively

- Examples: maitrī → mettā, auṣadha → osadha

- Sanskrit āya, ayā and avā reduce to Pali ā[39]

- Examples: katipayāhaṃ → katipāhaṃ, vaihāyasa → vehāsa, yāvagū → yāgu

- Sanskrit aya and ava likewise often reduce to Pali e and o

- Examples: dhārayati → dhāreti, avatāra → otāra, bhavati → hoti

- Sanskrit avi and ayū becomes Pali e (i.e. avi → ai → e) and o

- Examples: sthavira → thera, mayūra → mora

- Sanskrit ṛ appears in Pali as a, i or u, often agreeing with the vowel in the following syllable. ṛ also sometimes becomes u after labial consonants.

- Examples: kṛta → kata, tṛṣṇa → taṇha, smṛti → sati, ṛṣi → isi, dṛṣṭi → diṭṭhi, ṛddhi → iddhi, ṛju → uju, spṛṣṭa → phuṭṭha, vṛddha → vuddha

- Sanskrit long vowels are shortened before a sequence of two following consonants.

- Examples: kṣānti → khanti, rājya → rajja, īśvara → issara, tīrṇa → tiṇṇa, pūrva → pubba

Sound changes

- The Sanskrit sibilants ś, ṣ, and s merge as Pali s

- Examples: śaraṇa → saraṇa, doṣa → dosa

- The Sanskrit stops ḍ and ḍh become ḷ and ḷh between vowels (as in Vedic)

- Example: cakravāḍa → cakkavāḷa, virūḍha → virūḷha

General rules

- Many assimilations of one consonant to a neighboring consonant occurred in the development of Pali, producing a large number of geminate (double) consonants. Since aspiration of a geminate consonant is only phonetically detectable on the last consonant of a cluster, geminate kh, gh, ch, jh, ṭh, ḍh, th, dh, ph and bh appear as kkh, ggh, cch, jjh, ṭṭh, ḍḍh, tth, ddh, pph and bbh, not as khkh, ghgh etc.

- When assimilation would produce a geminate consonant (or a sequence of unaspirated stop+aspirated stop) at the beginning of a word, the initial geminate is simplified to a single consonant.

- Examples: prāṇa → pāṇa (not ppāṇa), sthavira → thera (not tthera), dhyāna → jhāna (not jjhāna), jñāti → ñāti (not ññāti)

- When assimilation would produce a sequence of three consonants in the middle of a word, geminates are simplified until there are only two consonants in sequence.

- Examples: uttrāsa → uttāsa (not utttāsa), mantra → manta (not mantta), indra → inda (not indda), vandhya → vañjha (not vañjjha)

- The sequence vv resulting from assimilation changes to bb.

- Example: sarva → savva → sabba, pravrajati → pavvajati → pabbajati, divya → divva → dibba, nirvāṇa → nivvāṇa → nibbāna

Total assimilation

Total assimilation, where one sound becomes identical to a neighboring sound, is of two types: progressive, where the assimilated sound becomes identical to the following sound; and regressive, where it becomes identical to the preceding sound.

Regressive assimilations

- Internal visarga assimilates to a following voiceless stop or sibilant

- Examples: duḥkṛta → dukkata, duḥkha → dukkha, duḥprajña → duppañña, niḥkrodha (=niṣkrodha) → nikkodha, niḥpakva (=niṣpakva) → nippakka, niḥśoka → nissoka, niḥsattva → nissatta

- In a sequence of two dissimilar Sanskrit stops, the first stop assimilates to the second stop

- Examples: vimukti → vimutti, dugdha → duddha, utpāda → uppāda, pudgala → puggala, udghoṣa → ugghosa, adbhuta → abbhuta, śabda → sadda

- In a sequence of two dissimilar nasals, the first nasal assimilates to the second nasal

- Example: unmatta → ummatta, pradyumna → pajjunna

- j assimilates to a following ñ (i.e., jñ becomes ññ)

- Examples: prajñā → paññā, jñāti → ñāti

- The Sanskrit liquid consonants r and l assimilate to a following stop, nasal, sibilant, or v

- Examples: mārga → magga, karma → kamma, varṣa → vassa, kalpa → kappa, sarva → savva → sabba

- r assimilates to a following l

- Examples: durlabha → dullabha, nirlopa → nillopa

- d sometimes assimilates to a following v, producing vv → bb

- Examples: udvigna → uvvigga → ubbigga, dvādaśa → bārasa (beside dvādasa)

- t and d may assimilate to a following s or y when a morpheme boundary intervenes

- Examples: ut+sava → ussava, ud+yāna → uyyāna

Progressive assimilations

- Nasals sometimes assimilate to a preceding stop (in other cases epenthesis occurs)

- Examples: agni → aggi, ātman → atta, prāpnoti → pappoti, śaknoti → sakkoti

- m assimilates to an initial sibilant

- Examples: smarati → sarati, smṛti → sati

- Nasals assimilate to a preceding stop+sibilant cluster, which then develops in the same way as such clusters without following nasals

- Examples: tīkṣṇa → tikṣa → tikkha, lakṣmī → lakṣī →lakkhī

- The Sanskrit liquid consonants r and l assimilate to a preceding stop, nasal, sibilant, or v

- Examples: prāṇa → pāṇa, grāma → gāma, śrāvaka → sāvaka, agra → agga, indra → inda, pravrajati → pavvajati → pabbajati, aśru → assu

- y assimilates to preceding non-dental/retroflex stops or nasals

- Examples: cyavati → cavati, jyotiṣ → joti, rājya → rajja, matsya → macchya → maccha, lapsyate → lacchyate → lacchati, abhyāgata → abbhāgata, ākhyāti → akkhāti, saṁkhyā → saṅkhā (but also saṅkhyā), ramya → ramma

- y assimilates to preceding non-initial v, producing vv → bb

- Example: divya → divva → dibba, veditavya → veditavva → veditabba, bhāvya → bhavva → bhabba

- y and v assimilate to any preceding sibilant, producing ss

- Examples: paśyati → passati, śyena → sena, aśva → assa, īśvara → issara, kariṣyati → karissati, tasya → tassa, svāmin → sāmī

- v sometimes assimilates to a preceding stop

- Examples: pakva → pakka, catvāri → cattāri, sattva → satta, dhvaja → dhaja

Partial and mutual assimilation

- Sanskrit sibilants before a stop assimilate to that stop, and if that stop is not already aspirated, it becomes aspirated; e.g. śc, st, ṣṭ and sp become cch, tth, ṭṭh and pph

- Examples: paścāt → pacchā, asti → atthi, stava → thava, śreṣṭha → seṭṭha, aṣṭa → aṭṭha, sparśa → phassa

- In sibilant-stop-liquid sequences, the liquid is assimilated to the preceding consonant, and the cluster behaves like sibilant-stop sequences; e.g. str and ṣṭr become tth and ṭṭh

- Examples: śāstra → śasta → sattha, rāṣṭra → raṣṭa → raṭṭha

- t and p become c before s, and the sibilant assimilates to the preceding sound as an aspirate (i.e., the sequences ts and ps become cch)

- Examples: vatsa → vaccha, apsaras → accharā

- A sibilant assimilates to a preceding k as an aspirate (i.e., the sequence kṣ becomes kkh)

- Examples: bhikṣu → bhikkhu, kṣānti → khanti

- Any dental or retroflex stop or nasal followed by y converts to the corresponding palatal sound, and the y assimilates to this new consonant, i.e. ty, thy, dy, dhy, ny become cc, cch, jj, jjh, ññ; likewise ṇy becomes ññ. Nasals preceding a stop that becomes palatal share this change.

- Examples: tyajati → cyajati → cajati, satya → sacya → sacca, mithyā → michyā → micchā, vidyā → vijyā → vijjā, madhya → majhya → majjha, anya → añya → añña, puṇya → puñya → puñña, vandhya → vañjhya → vañjjha → vañjha

- The sequence mr becomes mb, via the epenthesis of a stop between the nasal and liquid, followed by assimilation of the liquid to the stop and subsequent simplification of the resulting geminate.

- Examples: āmra → ambra → amba, tāmra → tamba

Epenthesis

An epenthetic vowel is sometimes inserted between certain consonant-sequences. As with ṛ, the vowel may be a, i, or u, depending on the influence of a neighboring consonant or of the vowel in the following syllable. i is often found near i, y, or palatal consonants; u is found near u, v, or labial consonants.

- Sequences of stop + nasal are sometimes separated by a or u

- Example: ratna → ratana, padma → paduma (u influenced by labial m)

- The sequence sn may become sin initially

- Examples: snāna → sināna, sneha → sineha

- i may be inserted between a consonant and l

- Examples: kleśa → kilesa, glāna → gilāna, mlāyati → milāyati, ślāghati → silāghati

- An epenthetic vowel may be inserted between an initial sibilant and r

- Example: śrī → sirī

- The sequence ry generally becomes riy (i influenced by following y), but is still treated as a two-consonant sequence for the purposes of vowel-shortening

- Example: ārya → arya → ariya, sūrya → surya → suriya, vīrya → virya → viriya

- a or i is inserted between r and h

- Example: arhati → arahati, garhā → garahā, barhiṣ → barihisa

- There is sporadic epenthesis between other consonant sequences

- Examples: caitya → cetiya (not cecca), vajra → vajira (not vajja)

Other changes

- Any Sanskrit sibilant before a nasal becomes a sequence of nasal followed by h, i.e. ṣṇ, sn and sm become ṇh, nh, and mh

- Examples: tṛṣṇa → taṇha, uṣṇīṣa → uṇhīsa, asmi → amhi

- The sequence śn becomes ñh, due to assimilation of the n to the preceding palatal sibilant

- Example: praśna → praśña → pañha

- The sequences hy and hv undergo metathesis

- Examples: jihvā → jivhā, gṛhya → gayha, guhya → guyha

- h undergoes metathesis with a following nasal

- Example: gṛhṇāti → gaṇhāti

- y is geminated between e and a vowel

- Examples: śreyas → seyya, Maitreya → Metteyya

- Voiced aspirates such as bh and gh on rare occasions become h

- Examples: bhavati → hoti, -ebhiṣ → -ehi, laghu → lahu

- Dental and retroflex sounds sporadically change into one another

- Examples: jñāna → ñāṇa (not ñāna), dahati → ḍahati (beside Pali dahati) nīḍa → nīla (not nīḷa), sthāna → ṭhāna (not thāna), duḥkṛta → dukkaṭa (beside Pali dukkata)

Exceptions

There are several notable exceptions to the rules above; many of them are common Prakrit words rather than borrowings from Sanskrit.

- ārya → ayya (beside ariya)

- guru → garu (adj.) (beside guru (n.))

- puruṣa → purisa (not purusa)

- vṛkṣa → rukṣa → rukkha (not vakkha)

Writing

Alphabet with diacritics

Emperor Ashoka erected a number of pillars with his edicts in at least three regional Prakrit languages in Brahmi script,[40] all of which are quite similar to Pali. Historically, the first written record of the Pali canon is believed to have been composed in Sri Lanka, based on a prior oral tradition. According to the Mahavamsa (the chronicle of Sri Lanka), due to a major famine in the country Buddhist monks wrote down the Pali canon during the time of King Vattagamini in 100 BCE.

Bilingual coins containing Pali written in the Kharosthi script and Greek writing were used by James Prinsep to decipher the Kharosthi abugida.[41] This script became particularly significant for the study of early Buddhism following the discovery of the Gandharan Buddhist texts.

The transmission of written Pali has retained a universal system of alphabetic values, but has expressed those values in a variety of different scripts.

In Sri Lanka, Pali texts were recorded in Sinhala script. Other local scripts, most prominently Khmer, Mon-Burmese, and in modern times Thai (since 1893) and Devanāgarī have been used to record Pali.

Since the 19th century, Pali has also been written in the Roman script. An alternate scheme devised by Frans Velthuis, called the Velthuis scheme (see § Text in ASCII) allows for typing without diacritics using plain ASCII methods, but is arguably less readable than the standard IAST system, which uses diacritical marks.

The Pali alphabetical order is as follows:

- a ā i ī u ū e o ṃ k kh g gh ṅ c ch j jh ñ ṭ ṭh ḍ ḍh ṇ t th d dh n p ph b bh m y r l ḷ v s h

ḷh, although a single sound, is written with ligature of ḷ and h.

Transliteration on computers

There are several fonts to use for Pali transliteration. However, older ASCII fonts such as Leedsbit PaliTranslit, Times_Norman, Times_CSX+, Skt Times, Vri RomanPali CN/CB etc., are not recommendable, they are deprecated, since they are not compatible with one another, and are technically out of date. Instead, fonts based on the Unicode standard are recommended.

However, not all Unicode fonts contain the necessary characters. To properly display all the diacritic marks used for romanized Pali (or for that matter, Sanskrit), a Unicode font must contain the following character ranges:

- Basic Latin: U+0000 – U+007F

- Latin-1 Supplement: U+0080 – U+00FF

- Latin Extended-A: U+0100 – U+017F

- Latin Extended-B: U+0180 – U+024F

- Latin Extended Additional: U+1E00 – U+1EFF

Some Unicode fonts freely available for typesetting Romanized Pali are as follows:

- The Pali Text Society recommends VU-Times and Gandhari Unicode for Windows and Linux Computers.

- The Tibetan & Himalayan Digital Library recommends Times Ext Roman, and provides links to several Unicode diacritic Windows and Mac fonts usable for typing Pali together with ratings and installation instructions. It also provides macros for typing diacritics in OpenOffice and MS Office.

- SIL: International provides Charis SIL and Charis SIL Compact, Doulos SIL, Gentium, Gentium Basic, Gentium Book Basic fonts. Of them, Charis SIL, Gentium Basic and Gentium Book Basic have all four styles (regular, italic, bold, bold-italic); so can provide publication quality typesetting.

- Libertine Openfont Project provides the Linux Libertine font (four serif styles and many Opentype features) and Linux Biolinum (four sans-serif styles) at the SourceForge.

- Junicode (short for Junius-Unicode) is a Unicode font for medievalists, but it provides all diacritics for typing Pali. It has four styles and some Opentype features such as Old Style for numerals.

- Thryomanes includes all the Roman-alphabet characters available in Unicode along with a subset of the most commonly used Greek and Cyrillic characters, and is available in normal, italic, bold, and bold italic.

- GUST (Polish TeX User Group) provides Latin Modern and TeX Gyre fonts. Each font has four styles, with the former finding most acceptance among the LaTeX users while the latter is a relatively new family. Of the latter, each typeface in the following families has nearly 1250 glyphs and is available in PostScript, TeX and OpenType formats.

- The TeX Gyre Adventor family of sans serif fonts is based on the URW Gothic L family. The original font, ITC Avant Garde Gothic, was designed by Herb Lubalin and Tom Carnase in 1970.

- The TeX Gyre Bonum family of serif fonts is based on the URW Bookman L family. The original font, Bookman or Bookman Old Style, was designed by Alexander Phemister in 1860.

- The TeX Gyre Chorus is a font based on the URW Chancery L Medium Italic font. The original, ITC Zapf Chancery, was designed in 1979 by Hermann Zapf.

- The TeX Gyre Cursor family of monospace serif fonts is based on the URW Nimbus Mono L family. The original font, Courier, was designed by Howard G. (Bud) Kettler in 1955.

- The TeX Gyre Heros family of sans serif fonts is based on the URW Nimbus Sans L family. The original font, Helvetica, was designed in 1957 by Max Miedinger.

- The TeX Gyre Pagella family of serif fonts is based on the URW Palladio L family. The original font, Palatino, was designed by Hermann Zapf in the 1940s.

- The TeX Gyre Schola family of serif fonts is based on the URW Century Schoolbook L family. The original font, Century Schoolbook, was designed by Morris Fuller Benton in 1919.

- The TeX Gyre Termes family of serif fonts is based on the Nimbus Roman No9 L family. The original font, Times Roman, was designed by Stanley Morison together with Starling Burgess and Victor Lardent.

- John Smith provides IndUni Opentype fonts, based upon URW++ fonts. Of them:

- IndUni-C is Courier-lookalike;

- IndUni-H is Helvetica-lookalike;

- IndUni-N is New Century Schoolbook-lookalike;

- IndUni-P is Palatino-lookalike;

- IndUni-T is Times-lookalike;

- IndUni-CMono is Courier-lookalike but monospaced;

- An English Buddhist monk titled Bhikkhu Pesala provides some Pali OpenType fonts he has designed himself. Of them:

- Acariya is a Garamond style typeface derived from Guru (regular, italic, bold, bold italic).

- Balava is a revival of Baskerville derived from Libre Baskerville (regular, italic, bold, bold italic).

- Cankama is a Gothic, Black Letter script. Regular style only.

- (Carita has been discontinued.)

- Garava was designed for body text with a generous x-height and economical copyfit. It includes Petite Caps (as OpenType Features), and Heavy styles besides the usual four styles (regular, italic, bold, bold italic).

- Guru is a condensed Garamond style typeface designed for economy of copy-fit. A hundred A4 pages of text set in Pali would be about 98 pages if set in Acariya, 95 if set in Garava or Times New Roman, but only 90 if set in Guru.(regular, italic, bold, bold italic styles).

- Hari is a hand-writing script derived from Allura by Robert E. Leuschke.(Regular style only).

- (Hattha has been discontinued)

- Jivita is an original Sans Serif typeface for body text. (regular, italic, bold, bold italic).

- Kabala is a distinctive Sans Serif typeface designed for display text or headings. Regular, italic, bold and bold italic styles.

- Lekhana is a Zapf Chancery clone, a flowing script that can be used for correspondence or body text. Regular, italic, bold and bold italic styles.

- Mahakampa is a hand-writing script derived from Great Vibes by Robert E. Leuschke. Regular type style.

- Mandala is designed for display text or headings. Regular, italic, bold and bold italic styles.

- Nacca is a hand-writing script derived from Dancing Script by Pablo Impallari and released on Font Squirrel. Regular type style.

- Odana is a calligraphic brush font suitable for headlines, titles, or short texts where a less formal appearance is wanted. Regular style only.

- Open Sans is a Sans Serif font suitable for body text. Ten type styles.

- Pali is a clone of Hermann Zapf's Palatino. Regular, italic, bold and bold italic styles.

- Sukhumala is derived from Sort Mills Goudy. Five type styles

- Talapanna is a clone of Goudy Bertham, with decorative gothic capitals and extra ligatures in the Private Use Area. Regular and bold styles.

- (Talapatta is discontinued.)

- Veluvana is another brush calligraphic font but basic Greek glyphs are taken from Guru. Regular style only.

- Verajja is derived from Bitstream Vera. Regular, italic, bold and bold italic styles.

- VerajjaPDA is a cut-down version of Verajja without symbols. For use on PDA devices. Regular, italic, bold and bold italic styles.

- He also provides some Pali keyboards for Windows XP.

- The font section of Alanwood's Unicode Resources have links to several general purpose fonts that can be used for Pali typing if they cover the character ranges above.

- John Smith provides IndUni Opentype fonts, based upon URW++ fonts. Of them:

Some of the latest fonts coming with Windows 7 can also be used to type transliterated Pali: Arial, Calibri, Cambria, Courier New, Microsoft Sans Serif, Segoe UI, Segoe UI Light, Segoe UI Semibold, Tahoma, and Times New Roman. Some of them have four styles each, hence usable in professional typesetting: Arial, Calibri and Segoe UI are sans-serif fonts, Cambria and Times New Roman are serif fonts and Courier New is a monospace font.

Text in ASCII

The Velthuis scheme was originally developed in 1991 by Frans Velthuis for use with his "devnag" Devanāgarī font, designed for the TeX typesetting system. This system of representing Pali diacritical marks has been used in some websites and discussion lists. However, as the Web itself and email software slowly evolve towards the Unicode encoding standard, this system has become almost unnecessary and obsolete.

The following table compares various conventional renderings and shortcut key assignments:

| character | ASCII Rendering | Character Name | Unicode Number | Key Combination | ALT Code | HTML Code |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ā | aa | a with macron | U+0101 | Alt+A | - | ā |

| ī | ii | i with macron | U+012B | Alt+I | - | ī |

| ū | uu | u with macron | U+016B | Alt+U | - | ū |

| ṃ | .m | m with dot below | U+1E43 | Alt+Ctrl+M | - | ṁ |

| ṇ | .n | n with dot under | U+1E47 | Alt+N | - | ṇ |

| ñ | ~n | n with tilde | U+00F1 | Alt+Ctrl+N | Alt+0241(NumPad) | ñ |

| ṭ | .t | t with dot below | U+1E6D | Alt+T | - | ṭ |

| ḍ | .d | d with dot below | U+1E0D | Alt+D | - | ḍ |

| ṅ | "n | n with dot above | U+1E45 | Ctrl+N | - | ṅ |

| ḷ | .l | l with dot below | U+1E37 | Alt+L | - | ḷ |

See also

- Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit

Footnotes

References

Citations

- Nagrajji (2003) "Pali language and the Buddhist Canonical Literature". Agama and Tripitaka, vol. 2: Language and Literature.

- Stargardt, Janice. Tracing Thoughts Through Things: The Oldest Pali Texts and the Early Buddhist Archaeology of India and Burma., Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, 2000, page 25.

- Norman, Kenneth Roy (1983). Pali Literature. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz. pp. 2–3. ISBN 3-447-02285-X.

- Wijithadhamma, Ven. M. (2015). "Pali Grammar and Kingship in Medieval Sri Lanka". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Sri Lanka. 60 (2): 49–58. JSTOR 44737021.

- Hazra, Kanai Lal. Pāli Language and Literature; a systematic survey and historical study. D.K. Printworld Lrd., New Delhi, 1994, page 19.

- A Dictionary of the Pali Language By Robert Cæsar Childers

- Bhikkhu Bodhi, In the Buddha's Words. Wisdom Publications, 2005, page 10.

- Collins, Steven (2003). "What Is Literature in Pali?". Literary Cultures in History: Reconstructions from South Asia. University of California Press. pp. 649–688. ISBN 978-0-520-22821-4. JSTOR 10.1525/j.ctt1ppqxk.19.

- Hirakawa, Akira. Groner, Paul. A History of Indian Buddhism: From Śākyamuni to Early Mahāyāna. 2007. p. 119

- Rupert Gethin (9 October 2008). Sayings of the Buddha: New Translations from the Pali Nikayas. OUP Oxford. pp. xxiv. ISBN 978-0-19-283925-1.

- Oberlies, Thomas (2001). Pāli: A Grammar of the Language of the Theravāda Tipiṭaka. Indian Philology and South Asian Studies, v. 3. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. p. 6. ISBN 3-11-016763-8. "Pāli as a MIA language is different from Sanskrit not so much with regard to the time of its origin than as to its dialectal base, since a number of its morphonological and lexical features betray the fact that it is not a direct continuation of Ṛgvedic Sanskrit; rather it descends from a dialect (or a number of dialects) which was (/were), despite many similarities, different from Ṛgvedic."

- Gornall, Alastair; Henry, Justin (2017). "Beautifully moral: cosmopolitan issues in medieval Pāli literary theory". Sri Lanka at the Crossroads of History. UCL Press. pp. 77–93. ISBN 978-1-911307-84-6. JSTOR j.ctt1qnw8bs.9.

- Anālayo (2012). "The Historical Value of the Pāli Discourses". Indo-Iranian Journal. 55 (3): 223–253. doi:10.1163/001972412X620187. JSTOR 24665100.

- Skilling, Peter (2014). "Reflections on the Pali Literature of Siam". From Birch Bark to Digital Data: Recent Advances in Buddhist Manuscript Research: Papers Presented at the Conference Indic Buddhist Manuscripts: The State of the Field. Stanford, June 15-19 2009. Austrian Academy of Sciences Press. pp. 347–366. doi:10.2307/j.ctt1vw0q4q.25. ISBN 978-3-7001-7581-0. JSTOR j.ctt1vw0q4q.25.

- Nepalese-German Manuscript Cataloguing Project. "A 1151-2 (Pālībhāṣāvinaya)".

- Ñāṇatusita, Bhikkhu (2014). "Pali Manuscripts of Sri Lanka". From Birch Bark to Digital Data: Recent Advances in Buddhist Manuscript Research: Papers Presented at the Conference Indic Buddhist Manuscripts: The State of the Field. Stanford, June 15-19 2009. Austrian Academy of Sciences Press. pp. 367–404. doi:10.2307/j.ctt1vw0q4q.26. ISBN 978-3-7001-7581-0. JSTOR j.ctt1vw0q4q.26.

The four oldest known Sinhalese Pali manuscripts date from the Dambadeniya kingdom period.......The oldest manuscript, the Cullavagga in the possession of the library of the Colombo National Museum, dates from the reign of King Parakramabahu II (1236-1237)......Another old manuscript dating from this period is a manuscript of the Paramatthamañjusā, the Visuddhimagga commentary......Another old manuscript, of the Sāratthadīpanī, a sub-commentary on the Samantapāsādikā Vinaya commentary......According to Wickramaratne (1967: 21) another 13th-century manuscript, containing the Mahavagga of the Vinaya Pitaka......Another source ascribes it to the 15th century, along with a Visuddhimagga manuscript......Another 15th-century manuscript of the Sāratthadīpanī is at the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris.

- Gethin, Rupert; Straube, Martin (2018). "The Pali Text Society's A Dictionary of Pāli". Bulletin of Chuo Academic Research Institute (Chuo Gakujutsu Kenkyūjo Kiyō). 47: 169–185.

- Buddhist India, ch. 9 Retrieved 14 June 2010.

- Hazra, Kanai Lal. Pāli Language and Literature; a systematic survey and historical study. D.K. Printworld Lrd., New Delhi, 1994, page 11.

- Hazra, Kanai Lal. Pāli Language and Literature; a systematic survey and historical study. D.K. Printworld Lrd., New Delhi, 1994, pages 1–44.

- Hazra, Kanai Lal. Pāli Language and Literature; a systematic survey and historical study. D.K. Printworld Lrd., New Delhi, 1994, page 29.

- Hazra, Kanai Lal. Pāli Language and Literature; a systematic survey and historical study. D.K. Printworld Lrd., New Delhi, 1994, page 20.

- K. R. Norman, Pāli Literature. Otto Harrassowitz, 1983, pages 1–7.

- Warder, A. K. Indian Buddhism. 2000. p. 284

- David Kalupahana, Nagarjuna: The Philosophy of the Middle Way. SUNY Press, 1986, page 19. The author refers specifically to the thought of early Buddhism here.

- Dispeller of Delusion, Pali Text Society, volume II, pages 127f

- Book, Chroniker Press (29 October 2012). Epitome of the Pali Canon. Lulu.com. ISBN 978-1-300-32715-8.

- Negi (2000), "Pali Language", Students' Britannica India, vol. 4

- Law, Bimala Churn (1931). "Non-Canonical Pali Literature". Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. 13 (2): 97–143. JSTOR 41688230.

- Von Hinüber, Oskar (1997). A Handbook of Pali Literature (1st Indian ed.). New Delhi: Munishiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. p. 83. ISBN 81-215-0778-2.

- "181 [95] – The home of the Paisaci – The home of the Paisaci – Page – Zeitschriften der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft – MENAdoc – Digital Collections". menadoc.bibliothek.Uni-Halle.de. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- Yao, Zhihua. The Buddhist Theory of Self-Cognition. 2012. p. 9

- "An Unpublished Fragment of Paisachi – Sanskrit – Pali". Scribd. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- Constance Jones; James D. Ryan (2006). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Infobase Publishing. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-8160-7564-5.

- Bashan A.L., The Wonder that was India, Picador, 2004, pp.394

- Perniola, Vito (1997). A Grammar of the Pali Language. p. 103. ISBN 0860133540.

- Geiger, Wilhelm (October 1996). Pali Literature and Language 2nd edition. Orintal Books Reptint Corporation Delhi_6. p. 65. ISBN 8170690773.

- Perniola, Vito (1997). A Grammar of the Pali Language. pp. 9, 10, 11. ISBN 0860133540.

- Jain, Danesh; Cardona, George (2007-07-26). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. p. 172.

- Inscriptions of Aśoka by Alexander Cunningham, Eugen Hultzsch. Calcutta: Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing. Calcutta: 1877

- Dias, Malini; Miriyagalla, Das (2007). "Brahmi Script in Relation to Mesopotamian Cuneiform". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Sri Lanka. 53: 91–108. JSTOR 23731201.

General sources

- See entries for "Pali" (written by K. R. Norman of the Pali Text Society) and "India—Buddhism" in The Concise Encyclopedia of Language and Religion (Sawyer ed.), ISBN 0-08-043167-4

- Müller, Edward (1995) [First published 1884]. Simplified Grammar of the Pali Language. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-1103-9.

- Silva, Lily de (1994). Pali Primer (first ed.). Vipassana Research Institute Publications. ISBN 81-7414-014-X.

- Warder, A. K. (1991). Introduction to Pali (third ed.). Pali Text Society. ISBN 0-86013-197-1.

Further reading

- American National Standards Institute. (1979). American National Standard system for the romanization of Lao, Khmer, and Pali. New York: The institute.

- Andersen, Dines (1907). A Pali Reader. Copenhagen: Gyldendalske Boghandel, Nordisk Forlag. p. 310. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- Perniola, V. (1997). Pali Grammar, Oxford, The Pali Text Society.

- Collins, Steven (2006). A Pali Grammar for Students. Silkworm Press.

- Gupta, K. M. (2006). Linguistic approach to meaning in Pali. New Delhi: Sundeep Prakashan. ISBN 81-7574-170-8

- Hazra, K. L. (1994). Pāli language and literature: a systematic survey and historical study. Emerging perceptions in Buddhist studies, no. 4–5. New Delhi: D.K. Printworld. ISBN 81-246-0004-X

- Müller, E. (2003). The Pali language: a simplified grammar. Trubner's collection of simplified grammars. London: Trubner. ISBN 1-84453-001-9

- Russell Webb (ed.) An Analysis of the Pali Canon, Buddhist Publication Society, Kandy; 1975, 1991 (see http://www.bps.lk/reference.asp Archived 3 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine)

- Soothill, W. E., & Hodous, L. (1937). A dictionary of Chinese Buddhist terms: with Sanskrit and English equivalents and a Sanskrit-Pali index. London: K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co.

- Bhikkhu Nanamoli. A Pāli-English Glossary of Buddhist technical terms. ISBN 9552400864

- Mahathera Buddhadatta (1998). Concise Pāli-English Dictionary. Quickly find the meaning of a word, without the detailed grammatical and contextual analysis. ISBN 8120806050

- Wallis, Glenn (2011). Buddhavacana, a Pali reader (PDF eBook). ISBN 192870686X.

- Lynn Martineau (1998). Pāli Workbook Pāli Vocabulary from the 10-day Vipassana Course of S. N. Goenka. ISBN 1928706045.