Persian Constitutional Revolution

The Persian Constitutional Revolution (Persian: مشروطیت, romanized: Mashrūtiyyat, or انقلاب مشروطه[10] Enghelāb-e Mashrūteh), also known as the Constitutional Revolution of Iran, took place between 1905 and 1911.[11] The revolution led to the establishment of a parliament in Persia (Iran) during the Qajar dynasty.[11][12]

| Persian Constitutional Revolution | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of constitutionalization attempts in Iran | |||||

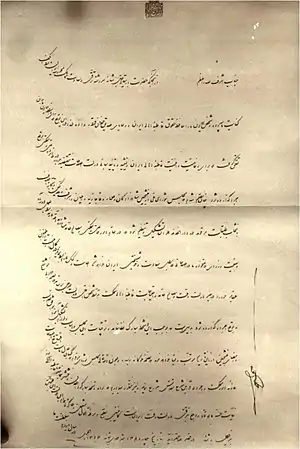

Royal proclamation by Mozaffar ad-Din Shah Qajar which established the constitutional monarchy on August 5, 1906 | |||||

| Date | 1905–1911 | ||||

| Location | Persia | ||||

| Resulted in |

| ||||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||||

| |||||

| Lead figures | |||||

| |||||

The revolution opened the way for fundamental change in Persia, heralding the modern era. It was a period of unprecedented debate in a burgeoning press, and new economic opportunities. Many groups fought to shape the course of the revolution, and all segments of society were in some way changed by it. The old order, which King Nassereddin Shah Qajar had struggled for so long to sustain, was finally replaced by new institutions, new forms of expression, and a new social and political order.

King Mozaffar ad-Din Shah Qajar signed the 1906 constitution shortly before his death. He was succeeded by Mohammad Ali Shah, who abolished the constitution and bombarded the parliament in 1908 with Russian and British support. This led to another pro-constitutional movement. The constitutionalist forces marched to Tehran, forced Muhammad Ali Shah's abdication in favor of his young son Ahmad Shah Qajar, and re-established the constitution in 1909.

The 1921 Persian coup d'état (Persian: کودتای ۳ اسفند ۱۲۹۹) refers to several major events which led to the establishment of the Pahlavi dynasty as Iran's ruling house in 1925. Iran's parliament amended the 1906–1907 constitution on December 12, 1925, replacing the 1797–1925 Qajar dynasty with the Pahlavi dynasty as the legitimate sovereigns of Iran.[13] The revolution was followed by the Jungle Movement of Gilan (1914-1921).

History

With the first provision signed by Muzzafir al-Din days before his death, Iran saw legislative reform vital to their goal of independence from Britain and Russia. The three main groups of the coalition seeking a constitution were the bazaar merchants, the ulama, and a small group of radical reformers. They shared the goal of ending royal corruption and ending dominance by foreign powers. According to the revolutionaries, the role of the shah was being used to keep the Qajar dynasty and other aristocrats wealthy at the expense of Iran's resources and economy. They argued that whilst Iran's oil industry was sold to the British, tax breaks on imports, exports and manufactured textiles destroyed Iran's economy (which had been supported by the bazaar merchants). Muzzafir al-Din accumulated a fortune in foreign debt while selling assets to pay interest, instead of investing in Iran. This sparked the revolt. The new fundamental law created a parliament, the Majles, and gave the legislature final approval of all loans and the budget. More power was divested from the shah with the supplementary fundamental law, which was passed by the National Assembly and signed by the new shah, Mohammad Ali, in October 1907. A committee of five mujtahids was to be created to ensure that new laws were compatible with the sharia. However, the committee never convened.[15] Despite the ulamas' efforts at independence from external dominance, Britain and Russia capitalized on Iran's weak government and signed the 1907 Anglo-Russian Convention dividing the country between them (with a neutral central zone). This constitutional period ended when the Majlis in Tehran's neutral zone dissolved over the issue of equal rights for non-Muslims; Russia then invaded and captured the city. Although Iran gained a constitution, Iranian independence was not achieved by the revolts.

Background

Weakness and extravagance continued during the brief reign of Mozaffar ad-Din Shah Qajar (1896–1907), who often relied on his chancellor to manage his decentralized state. His dire financial straits caused him to sign many concessions to foreign powers on trade items ranging from weapons to tobacco. The aristocracy, religious authorities, and educated elite began demanding a curb on royal authority and the establishment of the rule of law as their concern about foreign (especially Russian) influence grew.[14] Qajar had taken large loans from Russia and Britain to pay for his extravagant lifestyle and the cost of the government; the shah financed a royal tour of Europe in 1900 by borrowing ₽22 million from Russia, using Iranian customs receipts as collateral.[16]

First protests

In 1905, protests erupted about the imposition of Persian tariffs to repay the Russian loan for Mozaffar ad-Din Shah's royal tour.[16] In December of that year, two merchants in Tehran were bastinadoed for price-gouging. The city's merchants rebelled, closing its bazaar. The clergy followed suit as a result of the alliance formed during the Tobacco Protest.

The two protesting groups sought sanctuary in a Tehran mosque, but the government entered the mosque and dispersed them. The dispersal triggered a larger movement which sought refuge at a shrine outside Tehran. The shah yielded to the demonstrators on January 12, 1906, agreeing to dismiss his prime minister and transfer power to a "house of justice" (forerunner of the Iranian parliament). The basti protesters returned from the shrine in triumph, riding royal carriages and hailed by a jubilant crowd.[16]

During a fight in early 1906, government forces killed a sayyid (a descendant of Muhammad). In a skirmish shortly afterwards, Cossacks killed 22 protesters and injured 100.[17] The bazaar again closed and the ulama went on strike, a large number taking sanctuary in the holy city of Qom. Many merchants went to the British embassy in Tehran, which agreed to shelter the basti on the grounds of the embassy.[17]

Creation of the constitution

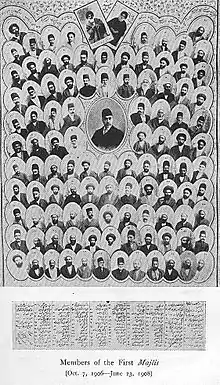

During the summer of 1906, about 12,000 men camped in the gardens of the British embassy in what has been called a "vast open-air school of political science".[17] Demand for a parliament (majlis) began, with the goal of limiting the power of the shah. Mozaffar ad-Din Shah agreed on a parliament in August 1906, and the first elections were held that fall. One hundred fifty-six members were elected, the overwhelming majority from Tehran and the merchant class.

The National Consultative Assembly first met in October 1906. The shah was old and frail, and attending the inauguration of parliament was one of his last official acts.[16] Mozaffar ad-Din Shah's son, Muhammad Ali, was unsympathetic to constitutionalism; the shah signed the constitution (modeled on the Belgian constitution) by December 31, 1906, making his power contingent on the will of the people, and died three days later.

Aftermath

Shah Muhammad Ali, the sixth Qajar shah, came to power in January 1907. The Anglo-Russian Convention, signed in August of that year, divided Iran into a Russian zone in the north and a British zone in the south; the center of the country was neutral. The British switched their support to the shah, abandoning the constitutionalists.[16] In 1908, the shah moved to "exploit the divisions within the ranks of the reformers" and eliminate the majlis.[16] Persia tried to remain free of Russian influence through resistance (via the majlis) to the shah's policies. Parliament appointed William Morgan Shuster Persia's treasurer-general. Russia issued an ultimatum to expel Shuster and suspend the parliament, occupying Tabriz.

Notable participants

Constitutionalists

.jpg.webp)

- Mirza Nasrullah Khan – First elected Prime Minister of Iran

- Mirza Jahangir Khan – Founder and editor of the Sur-e Esrafil newspaper

- Mirza Aqa Khan Kermani – Nationalist writer and literary critic

- Mirza Sayyed Mohammad Tabatabai

- Mohamad Vakil Altodjâr Yazdi Deputy Rasht

- Nikol Duman – Participated in the defense of Tabriz

- Seyed Jamal Vaez

- Hossein Ardabili – Active in Mashhad

- Aref Ghazvini

- Stepan Zorian

- Ali-Akbar Dehkhoda

- Mehdi Cont – activist in Kerman

- Sattar Khan – Revolutionary leader

- Bagher Khan – Sālār-e Melli (national chieftain)

- Mirza Kuchak Khan – Founder of a revolutionary movement based in the forests of Gilan Province

- Mirza Malkom Khan

- Khetcho – Armenian revolutionary leader

- Yeprem Khan – Armenian Iranian revolutionary leader. Wounded Sattar Khan while disarming the revolutionaries in Tehran as commander of Tehran's police force during the interim constitutionalist government.

- Arshak Gafavian – Armenian revolutionary leader

- Sardar Assad – Bakhtiari tribal leader whose forces captured Tehran in 1909

- Bibi Khanoom Astarabadi – Satirist, writer and pioneer of the Iranian women's movement

- Hassan Pirnia

- Heydar Latifiyan

- Ahmad Kasravi

- Amanollah Khan Zia' os-Soltan – aristocrat and landowner who was accused of a bomb attack on Mohammad Ali Shah and freed by British troops

- Mohammad-Taqi Bahar

- Sevkaretsi Sako

- Hassan Taqizadeh

- Mirza Abdul'Rahim Talibov Tabrizi – Intellectual and social reformer.

- Abdolhossein Teymourtash

- Abdol-Hossein Farman Farma

- Mohammad Vali Khan Tonekaboni – Leader of revolutionary forces from the northern provinces of Gilan and Mazandaran

- Howard Baskerville – American teacher who fought with the constitutionalists and was killed

- Mohammed Mosaddeq – Liberal nationalist and future prime minister

- Morteza Gholi Khan Hedayat

Monarchists

- Abdol Majid Mirza

- Sheikh Fazlollah Noori – Cleric who was hanged after the revolution

- Vladimir Liakhov – Russian colonel and commander of the Persian Cossack Brigade during the rule of Mohammad Ali Shah Qajar who shelled and besieged Parliament

- Eskandar Khan Davidkhanian – Deputy Commander of the Cossack Brigade

- Alexander Khan Setkhanian – second in command to Vladimir Liakhov

Religious leaders

- Mohammad-Kazem Khorasani, constitutionalist

- Sayyed Jamal ad-Din Esfahani, constitutionalist

- Sayyed Abdullah Behbahani, constitutionalist

- Mirza Sayyed Mohammad Tabatabai, constitutionalist

- Mirza Hussein Naini, constitutionalist

- Mohammed Kazem Yazdi, anti-constitutionalist

- Sheikh Fazlollah Nuri, anti-constitutionalist

- Mirza Abutaleb Zanjani, anti-constitutionalist

Usuli vs Islamist debate

The fourth Qajar King, Naser al-Din Shah was assassinated by Mirza Reza Kermani, a follower of Jamāl al-Dīn al-Afghānī, when he was visiting and praying in the Shah Abdul-Azim Shrine on 1 May 1896. At Mozaffar al-Din Shah's accession Persia faced a financial crisis, with annual governmental expenditures far in excess of revenues as a result of the policies of his father. King Mozaffar ad-Din Shah signed the 1906 constitution shortly before his death. The members of newly formed parliament stayed constantly in touch with Akhund Khurasani and whenever legislative bills were discussed, he was telegraphed the details for a juristic opinion.[18] In a letter dated June 3, 1907, the parliament told Akhund about a group of anti-constitutionalists who were trying to undermine legitimacy of democracy in the name of religious law. The trio replied:[18][19]

اساس این مجلس محترم مقدس بر امور مذکور مبتنی است. بر هر مسلمی سعی و اهتمام در استحکام و تشیید این اساس قویم لازم، و اقدام در موجبات اختلال آن محاده و معانده با صاحب شریعت مطهره علی الصادع بها و آله الطاهرین افضل الصلاه و السلام، و خیانت به دولت قوی شوکت است.

الاحقر نجل المرحوم الحاج میرزا خلیل قدس سره محمد حسین، حررّہ الاحقر الجانی محمد کاظم الخراسانی، من الاحقر عبدالله المازندرانی [20]

“Because we are aware of the intended reasons for this institution, it is therefore incumbent on every Muslim to support its foundation, and those who try to defeat it, and their action against it, are considered contrary to shari‘a.”

— Mirza Husayn Tehrani, Muhammad Kazim Khurasani, Abdallah Mazandaran.

At the dawn of the democratic movement, Sheikh Fadlullah Nouri, supported the sources of emulation in Najaf in their stance on constitutionalism and the belief that people must counter the autocratic regime in the best way, that is constitution of legislature and limiting the powers of the state; hence, once constitutional movement began, he made speeches and distributed tracts to insist on this important thing. However, when the new Shah, Muhammad Ali Shah Qajar, decided to role back democracy and establish his authority by military and foreign support, Shaikh Fazlullah sided with Kiing's court.[21]

Meanwhile, the new Shah had understood that he could not roll back the constitutional democracy by royalist ideology, and therefore he decided to use the religion card.[22] Nouri was a rich and high-ranking Qajar court official responsible for conducting marriages and contracts. He also handled wills of wealthy men and collected religious funds.[23] Nouri was opposed to the very foundations of the institution of parliament. He led a large group of followers and began a round-the-clock sit-in in the Shah Abdul Azim shrine on June 21, 1907 which lasted till September 16, 1907. He generalized the idea of religion as a complete code of life to push for his own agenda. He believed democracy will allow for “teaching of chemistry, physics and foreign languages”, that would result in spread of Atheism.[24] He bought a printing press and launched a newspaper of his own for propaganda purposes, “Ruznamih-i-Shaikh Fazlullah”, and published leaflets.[25] He believed that the ruler was accountable to no institution other than God and people have no right to limit the powers or question the conduct of the King. He declared that those who supported democratic form of government were faithless and corrupt, and apostates.[26] He hated the idea of female education and said that girls schools were brothels.[27] Alongside his vicious propaganda against women education, he also opposed allocation of funds for modern industry, modern ways of governance, equal rights for all citizens irrespective of their religion and freedom of press. He believed that people were cattle, but paradoxically, he wanted to “awaken the muslim brethren”.[28]

The anti-democracy clerics incited violence and one such cleric said that getting in the proximity of the parliament was a bigger sin than adultery, robbery and murder.[29] In Zanjan, Mulla Qurban Ali Zanjani mobilized a force of six hundred thugs who looted shops of pro-democracy merchants and took hold of the city for several days and killed the representative Sa'd al-Saltanih.[30] Nouri himself recruited mercenaries from criminal gangs to harass the supporters of democracy. On December 22, 1907, Nouri led a mob towards Tupkhanih Square and attacked merchants and looted stores.[31] Nouri's ties to the court of monarchy and landlords reinforced his fanaticism. He even contacted the Russian embassy for support and his men delivered sermons against democracy in mosques, resulting in chaos.[32] Akhund Khurasani was consulted on the matter and in a letter dated December 30, 1907, the three Marja's said:

چون نوری مخل آسائش و مفسد است، تصرفش در امور حرام است.

محمد حسین (نجل) میرزا خلیل، محمد کاظم خراسانی، عبدالله مازندرانی [34]

“Because Nouri is causing trouble and sedition, his interfering in any affair is forbidden.”

— Mirza Husayn Tehrani, Muhammad Kazim Khurasani, Abdallah Mazandaran.

However, Nouri continued his activities and a few weeks later Akhund Khurasani and his fellow Marja's argued for his expulsion from Tehran:[35]

رفع اغتشاشات حادثه و تبعید نوری را عاجلاً اعلام.

الداعی محمد حسین نجل المرحوم میرزا خلیل، الداعی محمد کاظم الخراسانی، عبدالله المازندرانی [36]

“Restore peace and expel Nouri as quickly as possible.”

— Mirza Husayn Tehrani, Muhammad Kazim Khurasani, Abdallah Mazandaran.

Mirza Ali Aqa Tabrizi, the enlightened Thiqa tul-islam from Tabriz, opposed Nuri saying that only the opinion of the sources of emulation is worthy of consideration in the matters of faith.[37] He wrote:

He who wins his own soul, protects his religion, is against following his desires and is obedient to the command of his Master; that is the person whom the people should take as their model.[38]

And

Let us consider the idea that the constitution is against Sharia law: all oppositions of this kind are in vain because the hujjaj al-islam of the atabat, who are today the models (marja') and the refuge (malija) of all Shiites, have issued clear fatwas that uphold the necessity of the Constitution. Aside from their words, they have also shown this by their actions. They see in Constitution the support for splendour of Islam.[38]

He firmly opposed the idea of a supervisory committee of Tehran's clerics censoring the conduct of the parliament, and said that:

this delicate subject shall be submitted to the atabat, . . . we don't have the right to entrust government to a group of four or five mullahs from Tehran.[38]

As far as Nouri's argument was concerned, Akhund Khurasani refuted it in a light tone by saying that he supported the “parliament at Baharistan Square”, questioning the legitimacy of Nouri's assembly at Shah Abdul Azim shrine and their right to decide for the people.[39] Responding to a question about Nouri's arguments, Akhund Muhammad Kazim Khurasani said:[40]

Persian: سلطنت مشروعه آن است کہ متصدی امور عامه ی ناس و رتق و فتق کارهای قاطبه ی مسلمین و فیصل کافه ی مهام به دست شخص معصوم و موید و منصوب و منصوص و مأمور مِن الله باشد مانند انبیاء و اولیاء و مثل خلافت امیرالمومنین و ایام ظهور و رجعت حضرت حجت، و اگر حاکم مطلق معصوم نباشد، آن سلطنت غیرمشروعه است، چنان کہ در زمان غیبت است و سلطنت غیرمشروعه دو قسم است، عادله، نظیر مشروطه کہ مباشر امور عامه، عقلا و متدینین باشند و ظالمه و جابره است، مثل آنکه حاکم مطلق یک نفر مطلق العنان خودسر باشد. البته به صریح حکم عقل و به فصیح منصوصات شرع «غیر مشروعه ی عادله» مقدم است بر «غیرمشروعه ی جابره». و به تجربه و تدقیقات صحیحه و غور رسی های شافیه مبرهن شده که نُه عشر تعدیات دوره ی استبداد در دوره ی مشروطیت کمتر میشود و دفع افسد و اقبح به فاسد و به قبیح واجب است.[41]

English: “According to Shia doctrine, only the infallible Imam has the right to govern, to run the affairs of the people, to solve the problems of the Muslim society and to make important decisions. As it was in the time of the prophets or in the time of the caliphate of the commander of the faithful, and as it will be in the time of the reappearance and return of the Mahdi. If the absolute guardianship is not with the infallible then it will be a non-islamic government. Since this is a time of occultation, there can be two types of non-islamic regimes: the first is a just democracy in which the affairs of the people are in the hands of faithful and educated men, and the second is a government of tyranny in which a dictator has absolute powers. Therefore, both in the eyes of the Sharia and reason what is just prevails over the unjust. From human experience and careful reflection it has become clear that democracy reduces the tyranny of state and it is obligatory to give precedence to the lesser evil.”

— Muhammad Kazim Khurasani

As “sanctioned by sacred law and religion”, Akhund believes, a theocratic government can only be formed by the infallible Imam.[42] Nouri interpreted Sharia in a self-serving and shallow way, unlike Akhund Khurasani who, as a well received source of emulation, viewed the adherence to religion in a society beyond one person or one interpretation.[43] While Nouri confused Sharia with written constitution of a modern society, Akhund Khurasani understood the difference and the function of the two.[44]

Nouri tried to get support from Ayatullah Kazim Yazdi, another prominent Marja of Najaf. He was apolitical, and therefore during the Iranian Constitutional Revolution, he stayed neutral most of the times and seldom issued any political statement.[45] Contrary to Akhund Khorasani, he thought that Usulism did not offer the liberty to support constitutional politics. In his view, politics was beyond his expertise and therefore he avoided taking part in it. [46] While Akhund Khorasani was an eminent Marja' in Najaf, many imitators prayed behind Kazim Yazdi too, as his lesson on rulings (figh) was famous.[47] In other words both Mohammad Kazem and Khorasani had constituted a great Shia school in Najaf although they had different views in politics at the same time.[48] However, he was not fully supportive of Fazlullah Nouri and Muhammad Ali Shah, therefore, when parliament asked him to review the final draft of constitution, he suggested some changes and signed the document.[49] He said that modern industries were permissible unless explicitly prohibited by Sharia.[50] He also agreed with teaching of modern sciences, and added that the state should not intervene the centers of religious learning (Hawza). He wasn't against formation of organizations and societies that do not create chaos, and in this regard there was no difference between religious and non-religious organizations.[50] In law-making, unlike Nouri, he separated the religious (Sharia) and public law (Urfiya). His opinion was that the personal and family matters should be settled in religious courts by jurists, and the governmental affaris and matters of state should be taken care of by modern judiciary. Parliament added article 71 and 72 into the constitution based on his opinions.[51] Ayatullah Yazdi said that as long as modern constitution did not force people to do what was forbidden by Sharia and refrain from religious duties, there was no reason to oppose democratic rule and the government had the right to prosecute wrong doers.[52] The Revolutional Tribunal declared Nouri guilty of inciting mobs against the constitutionalists and issuing fatwas declaring parliamentary leaders "apostates", "atheists," "secret Freemasons" and koffar al-harbi (warlike pagans) whose blood ought to be shed by the faithful.[53][54]

Execution

Nouri allied himself with the new Shah, Mohammad Ali Shah, who, with the assistance of Russian troops staged a coup against the Majlis (parliament) in 1907. In 1909, however, constitutionalists marched onto Tehran (the capital of Iran). Nouri was arrested, tried and found guilty of "sowing corruption and sedition on earth,"[54] and in July 1909, Nouri was hanged as a traitor.

See also

- Young Turk Revolution

- History of Iran

- History of the Iranian Constitutional Revolution by Ahmad Kasravi

- Intellectual movements in Iran

- Muhammad Kazim Khurasani

- Mirza Husayn Tehrani

- Abdallah Mazandarani

- Mirza Ali Aqa Tabrizi

- Mirza Sayyed Mohammad Tabatabai

- Seyyed Abdollah Behbahani

- Ruhollah Khomeini

- Islamic fundamentalism in Iran

- Iranian Revolution of 1979

- Tobacco Protest

- List of modern conflicts in the Middle East

- Triumph of Tehran

- Secularism in Iran

- Ibn al-Sheikh

- Women in Constitutional Revolution

References

- Abrahamian, Ervand (1982). Iran Between Two Revolutions. Princeton University Press. pp. 76–77. ISBN 0-691-10134-5.

- Abrahamian, Ervand (1982). Iran Between Two Revolutions. Princeton University Press. pp. 83. ISBN 0-691-10134-5.

- Abrahamian, Ervand (1982). Iran Between Two Revolutions. Princeton University Press. pp. 81. ISBN 0-691-10134-5.

- Abrahamian, Ervand (1982). Iran Between Two Revolutions. Princeton University Press. pp. 84. ISBN 0-691-10134-5.

- Abrahamian, Ervand (1982). Iran Between Two Revolutions. Princeton University Press. pp. 97. ISBN 0-691-10134-5.

- Abrahamian, Ervand (1982). Iran Between Two Revolutions. Princeton University Press. pp. 95. ISBN 0-691-10134-5.

- Abrahamian, Ervand (1982). Iran Between Two Revolutions. Princeton University Press. pp. 91. ISBN 0-691-10134-5.

- Berberian, Houri (2001). Armenians and the Iranian Constitutional Revolution of 1905–1911. Westview Press. pp. 116–117. ISBN 978-0-8133-3817-0.

- Jack A. Goldstone. The Encyclopedia of Political Revolutions Routledge, 29 apr. 2015 ISBN 1135937583 p 245

- Tilmann J. Röder, "The Separation of Powers: Historical and Comparative Perspectives" in Rainer Grote and Tilmann J. Röder, Constitutionalism in Islamic Countries (Oxford University Press 2012), p. 321-372. The article includes an English translation of the following documents: The Fundamental Law (Qanun-e Asasi-e Mashruteh) of the Iranian Empire of 14th Dhu-‘l-Qa’dah 1324 (December 30, 1906); The Amendment of the Fundamental Law of the Iranian Empire of 29th Sha’ban 1325 (October 7, 1907).

- Amanat 1992, pp. 163–176.

- "CONSTITUTIONAL REVOLUTION". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. VI, Fasc. 2. 1992. pp. 163–216.

- "Pahlavi Dynasty - Dictionary definition of Pahlavi Dynasty - Encyclopedia.com: FREE online dictionary".

- W. Morgan Shuster, The Strangling of Persia, 3rd printing (T. Fisher Unwin, London, 1913), pp. 48, 119, 179. According to Shuster (p. 48), "Five days later [measured from February 1st] the Persian Minister of Finance, Saniu'd-Dawleh was shot and killed in the streets of Teheran by two Georgians, who also succeeded in wounding four of the Persian police before they were captured. The Russian consular authorities promptly refused to allow these men to be tried by the Persian Government, and took them out of the country under Russian protection, claiming that they would be suitably punished."

Mohammad-Reza Nazari. "The retreat by the Parliament in overseeing the financial matters is a retreat of democracy" (in Persian). Mardom-Salari, No. 1734, 20 Bahman 1386 AH (9 February 2008). Archived from the original on April 27, 2009. - Amanat, Abbas (2017). Iran: A Modern History. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 438. ISBN 978-0300248937.

- Mackey, Sandra The Iranians : Persia, Islam and the Soul of a Nation, New York : Dutton, c1996. p.150-55

- Abrahamian, Ervand, Iran Between Two Revolutions, Princeton University Press, 1982, p. 84

- Farzaneh 2015, pp. 173–174.

- Bayat, Mangol (1991). Iran's first revolution: Shi'ism and the constitutional revolution of 1905-1909. Studies in Middle Eastern history. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. p. 181. ISBN 9780195068221. OCLC 1051306470. Retrieved April 30, 2022.

- محسن کدیور، ”سیاست نامه خراسانی“، ص۱۶۹، طبع دوم، تہران سنه ۲۰۰۸ء

- Arjomand, Said Amir (November 16, 1989). The Turban for the Crown: The Islamic Revolution in Iran. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 50–52. ISBN 978-0-19-504258-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Arjomand, Said Amir (16 November 1989). The Turban for the Crown: The Islamic Revolution in Iran. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 48–49. ISBN 978-0-19-504258-0.

- Farzaneh 2015, pp. 195.

- Farzaneh 2015, pp. 196.

- Farzaneh 2015, pp. 197.

- Farzaneh 2015, pp. 198.

- Farzaneh 2015, pp. 199.

- Arjomand, Said Amir (16 November 1989). The Turban for the Crown: The Islamic Revolution in Iran. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-19-504258-0.

- Farzaneh 2015, pp. 193.

- Farzaneh 2015, pp. 160.

- Farzaneh 2015, p. 205.

- Bayat, Mangol (1991). “Iran's First Revolution: Shi'ism and the Constitutional Revolution of 1905-1909”. Studies in Middle Eastern History. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-19-506822-1.

- Farzaneh, Mateo Mohammad (2015). “The Iranian Constitutional Revolution and the Clerical Leadership of Khurasani”. Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-8156-5311-0.

- محسن کدیور، ”سیاست نامه خراسانی“، ص۱۷۷، طبع دوم، تہران سنه ۲۰۰۸ء

- Hermann, Denis (1 May 2013). “Akhund Khurasani and the Iranian Constitutional Movement”. Middle Eastern Studies. 49 (3): p. 437. doi:10.1080/00263206.2013.783828. ISSN 0026-3206.

- محسن کدیور، ”سیاست نامه خراسانی“، ص١٨٠، طبع دوم، تہران سنه ۲۰۰۸ء

- Hermann 2013, p. 438.

- Hermann 2013, p. 439.

- Farzaneh, Mateo Mohammad (2015). “The Iranian Constitutional Revolution and the Clerical Leadership of Khurasani”. Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-8156-5311-0.

- Farzaneh 2015, pp. 162.

- محسن کدیور، ”سیاست نامه خراسانی“، ص ۲۱۴-۲۱۵، طبع دوم، تہران سنه ۲۰۰۸ء

- Hermann 2013, pp. 434.

- Farzaneh 2015, pp. 200.

- Farzaneh 2015, pp. 201.

- Arjomand, Said Amir (16 November 1989). The Turban for the Crown: The Islamic Revolution in Iran. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-19-504258-0.

- Farzaneh 2015, p. 214.

- Mottahedeh, R. (2014). The Mantle of the Prophet. Oneworld Publications. ISBN 9781780747385. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- Hann, G.; Dabrowska, K.; Greaves, T.T. (2015). Iraq: The ancient sites and Iraqi Kurdistan. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 292. ISBN 9781841624884. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- Farzaneh 2015, p. 215.

- Farzaneh 2015, p. 216.

- Farzaneh 2015, p. 217.

- Farzaneh 2015, p. 218.

- Taheri, Amir, The Spirit of Allah by Amir Adler and Adler (1985), pp. 45–6

- Abrahamian, Ervand, Tortured Confessions by Ervand Abrahamian, University of California Press, 1999 p. 24

- Hermann 2013, p. 440.

Sources

- Amanat, Abbas (1992). "Constitutional Revolution i. Intellectual background". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. VI, Fasc. 2. pp. 163–176.

- Ahmad Kasravi, Tārikh-e Mashruteh-ye Iran (تاریخ مشروطهٔ ایران) (History of the Iranian Constitutional Revolution) (in Persian) 951 p. (Negāh Publications, Tehran, 2003), ISBN 964-351-138-3. Note: This book is also available in two volumes, published by Amir Kabir Publications in 1984. Amir Kabir's 1961 edition is in one 934-page volume.

- Ahmad Kasravi, History of the Iranian Constitutional Revolution: Tarikh-e Mashrute-ye Iran, Volume I, translated into English by Evan Siegel, 347 p. (Mazda Publications, Costa Mesa, California, 2006). ISBN 1-56859-197-7

- Mehdi Malekzādeh, Tārikh-e Enqelāb-e Mashrutyyat-e Iran (تاريخ انقلاب مشروطيت ايران) (The History of the Constitutional Revolution of Iran) in 7 volumes, published in 3 volumes (1697 pp.) (Sokhan Publications, Tehran, 2004, 1383 AH). ISBN 964-372-095-0

Further reading

- Ansari, Ali (2016). "Constitutional Revolution in Iran". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE. Brill Online. ISSN 1873-9830.

- Mangol, Bayat (1991). Iran's First Revolution: Shi'ism and the Constitutional Revolution of 1905-1909. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-506822-1.

- Farzaneh, Mateo Mohammad (March 2015). Iranian Constitutional Revolution and the Clerical Leadership of Khurasani. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 9780815633884. OCLC 931494838.

- Browne, Edward G., The Persian Constitutional Movement. British Academy, 1918.

- Browne, Edward G., "The Persian Revolution of 1905-1909", Mage Publishers (July 1995). ISBN 0-934211-45-0

- Afary, Janet, "The Iranian Constitutional Revolution, 1906-1911", Columbia University Press. 1996. ISBN 0-231-10351-4

- Foran, John. "The Strengths and Weaknesses of Iran’s Populist Alliance: A Class Analysis of the Constitutional Revolution of 1905 - 1911", Theory and Society, Vol. 20, No. 6 (Dec 1991), pp. 795–823. JSTOR

- Hermann, Denis (May 1, 2013). "Akhund Khurasani and the Iranian Constitutional Movement". Middle Eastern Studies. 49 (3): 430–453. doi:10.1080/00263206.2013.783828. ISSN 0026-3206. JSTOR 23471080. S2CID 143672216.

- Ahmad Kasravi, Tārikh-e Mashruteh-ye Iran (تاریخ مشروطهٔ ایران) (History of the Iranian Constitutional Revolution), in Persian, 951 p. (Negāh Publications, Tehran, 2003), ISBN 964-351-138-3. Note: This book is also available in two volumes, published by Amir Kabir Publications in 1984. Amir Kabir's 1961 edition is in one volume, 934 pages.

- Ahmad Kasravi, History of the Iranian Constitutional Revolution: Tārikh-e Mashrute-ye Iran, Volume I, translated into English by Evan Siegel, 347 p. (Mazda Publications, Costa Mesa, California, 2006). ISBN 1-56859-197-7

External links

- Reza Jamāli in conversation with Dr Abbās Amānat, Professor of History and International and Area Studies at University of Yale, in Persian, Radio Zamaneh, August 7, 2008 (Audio recording).

- Shokā Sahrāi, Photographs of the Constitutional Revolution of Iran, in Persian, Jadid Online, 2007.

Slide Show, narrated by Dr Bāqer Āqeli, Jadid Online, 2007: (4 min 30 sec). - Constitutional Revolution of Iran