Caesarean section

Caesarean section, also known as C-section or caesarean delivery, is the surgical procedure by which one or more babies are delivered through an incision in the mother's abdomen, often performed because vaginal delivery would put the baby or mother at risk.[2] Reasons for the operation include obstructed labor, twin pregnancy, high blood pressure in the mother, breech birth, and problems with the placenta or umbilical cord.[2][3] A caesarean delivery may be performed based upon the shape of the mother's pelvis or history of a previous C-section.[2][3] A trial of vaginal birth after C-section may be possible.[2] The World Health Organization recommends that caesarean section be performed only when medically necessary.[3][4] Most C-sections are performed without a medical reason, upon request by someone, usually the mother.[2]

| Caesarean section | |

|---|---|

A team of four performing a caesarean section[1] | |

| Other names | C-section, cesarean section, caesarean delivery |

| Specialty | Obstetrics, gynaecology, surgery, neonatology, pediatrics, family medicine |

| ICD-10-PCS | 10D00Z0 |

| ICD-9-CM | 74 |

| MeSH | D002585 |

| MedlinePlus | 002911 |

A C-section typically takes 45 minutes to an hour.[2] It may be done with a spinal block, where the woman is awake, or under general anesthesia.[2] A urinary catheter is used to drain the bladder, and the skin of the abdomen is then cleaned with an antiseptic.[2] An incision of about 15 cm (6 inches) is then typically made through the mother's lower abdomen.[2] The uterus is then opened with a second incision and the baby delivered.[2] The incisions are then stitched closed.[2] A woman can typically begin breastfeeding as soon as she is out of the operating room and awake.[5] Often, several days are required in the hospital to recover sufficiently to return home.[2]

C-sections result in a small overall increase in poor outcomes in low-risk pregnancies.[3] They also typically take longer to heal from, about six weeks, than vaginal birth.[2] The increased risks include breathing problems in the baby and amniotic fluid embolism and postpartum bleeding in the mother.[3] Established guidelines recommend that caesarean sections not be used before 39 weeks of pregnancy without a medical reason.[6] The method of delivery does not appear to have an effect on subsequent sexual function.[7]

In 2012, about 23 million C-sections were done globally.[8] The international healthcare community has previously considered the rate of 10% and 15% to be ideal for caesarean sections.[4] Some evidence finds a higher rate of 19% may result in better outcomes.[8] More than 45 countries globally have C-section rates less than 7.5%, while more than 50 have rates greater than 27%.[8] Efforts are being made to both improve access to and reduce the use of C-section.[8] In the United States as of 2017, about 32% of deliveries are by C-section.[9] The surgery has been performed at least as far back as 715 BC following the death of the mother, with the baby occasionally surviving.[10] Descriptions of mothers surviving date back to 1500 AD, with earlier attests to ancient times (including the apocryphal account of Julius Caesar being born by caesarean section, a commonly stated origin of the term).[10] With the introduction of antiseptics and anesthetics in the 19th century, survival of both the mother and baby, and thus the procedure, became significantly more common.[10][11]

Uses

Caesarean section is recommended when vaginal delivery might pose a risk to the mother or baby. C-sections are also carried out for personal and social reasons on maternal request in some countries.

Medical uses

Complications of labor and factors increasing the risk associated with vaginal delivery include:

- Abnormal presentation (breech or transverse positions).

- Prolonged labor or a failure to progress (obstructed labour, also known as dystocia)

- Fetal distress

- Cord prolapse

- Uterine rupture or an elevated risk thereof

- Uncontrolled hypertension, pre-eclampsia,[12] or eclampsia in the mother

- Tachycardia in the mother or baby after amniotic rupture (the waters breaking)

- Placenta problems (placenta praevia, placental abruption or placenta accreta)

- Failed labor induction

- Failed instrumental delivery (by forceps or ventouse (Sometimes, a trial of forceps/ventouse delivery is attempted, and if unsuccessful, the baby will need to be delivered by caesarean section.)

- Large baby weighing > 4,000 grams (macrosomia)

- Umbilical cord abnormalities (vasa previa, multilobate including bilobate and succenturiate-lobed placentas, velamentous insertion)

Other complications of pregnancy, pre-existing conditions, and concomitant disease, include:

- Previous (high risk) fetus

- HIV infection of the mother with a high viral load (HIV with a low maternal viral load is not necessarily an indication for caesarean section)

- An outbreak of genital herpes in the third trimester[13] (which can cause infection in the baby if born vaginally)

- Previous classical (longitudinal) caesarean section

- Previous uterine rupture

- Prior problems with the healing of the perineum (from previous childbirth or Crohn's disease)

- Bicornuate uterus

- Rare cases of posthumous birth after the death of the mother

Other

- Decreasing experience of accoucheurs with the management of breech presentation. Although obstetricians and midwives are extensively trained in proper procedures for breech presentation deliveries using simulation mannequins, there is decreasing experience with actual vaginal breech delivery, which may increase the risk.[14]

Prevention

The prevalence of caesarean section is generally agreed to be higher than needed in many countries, and physicians are encouraged to actively lower the rate, as a caesarean rate higher than 10–15% is not associated with reductions in maternal or infant mortality rates,[4] although some evidence support that a higher rate of 19% may result in better outcomes.[8]

Some of these efforts are: emphasizing a long latent phase of labor is not abnormal and not a justification for C-section; a new definition of the start of active labor from a cervical dilatation of 4 cm to a dilatation of 6 cm; and allowing women who have previously given birth to push for at least 2 hours, with 3 hours of pushing for women who have not previously given birth, before labor arrest is considered.[3] Physical exercise during pregnancy decreases the risk.[15] Additionally, results from a 2021 systematic review of the evidence on outpatient cervical ripening found that in women with low-risk pregnancies, the risk of cesarean delivery with harms to the mother or child were not significantly different than when done in an inpatient setting.[16]

Risks

Adverse outcomes in low-risk pregnancies occur in 8.6% of vaginal deliveries and 9.2% of caesarean section deliveries.[3]

Mother

In those who are low risk, the risk of death for caesarean sections is 13 per 100,000 vs. for vaginal birth 3.5 per 100,000 in the developed world.[3] The United Kingdom National Health Service gives the risk of death for the mother as three times that of a vaginal birth.[17]

In Canada, the difference in serious morbidity or mortality for the mother (e.g. cardiac arrest, wound hematoma, or hysterectomy) was 1.8 additional cases per 100.[18] The difference in in-hospital maternal death was not significant.[18]

A caesarean section is associated with risks of postoperative adhesions, incisional hernias (which may require surgical correction), and wound infections.[19] If a caesarean is performed in an emergency, the risk of the surgery may be increased due to a number of factors. The patient's stomach may not be empty, increasing the risk of anaesthesia.[20] Other risks include severe blood loss (which may require a blood transfusion) and post-dural-puncture spinal- headaches.[19]

Wound infections occur after caesarean sections at a rate of 3–15%.[21] The presence of chorioamnionitis and obesity predisposes the woman to develop a surgical site infection.[21]

Women who had caesarean sections are more likely to have problems with later pregnancies, and women who want larger families should not seek an elective caesarean unless medical indications to do so exist. The risk of placenta accreta, a potentially life-threatening condition which is more likely to develop where a woman has had a previous caesarean section, is 0.13% after two caesarean sections, but increases to 2.13% after four and then to 6.74% after six or more. Along with this is a similar rise in the risk of emergency hysterectomies at delivery.[22]

Mothers can experience an increased incidence of postnatal depression, and can experience significant psychological trauma and ongoing birth-related post-traumatic stress disorder after obstetric intervention during the birthing process.[23] Factors like pain in the first stage of labor, feelings of powerlessness, intrusive emergency obstetric intervention are important in the subsequent development of psychological issues related to labor and delivery.[23]

Subsequent pregnancies

Women who have had a caesarean for any reason are somewhat less likely to become pregnant again as compared to women who have previously delivered only vaginally.[24]

Women who had just one previous caesarean section are more likely to have problems with their second birth.[3] Delivery after previous caesarean section is by either of two main options:

- Vaginal birth after caesarean section (VBAC)

- Elective repeat caesarean section (ERCS)

Both have higher risks than a vaginal birth with no previous caesarean section. A vaginal birth after caesarean section (VBAC) confers a higher risk of uterine rupture (5 per 1,000), blood transfusion or endometritis (10 per 1,000), and perinatal death of the child (0.25 per 1,000).[25] Furthermore, 20% to 40% of planned VBAC attempts end in caesarean section being needed, with greater risks of complications in an emergency repeat caesarean section than in an elective repeat caesarean section.[26][27] On the other hand, VBAC confers less maternal morbidity and a decreased risk of complications in future pregnancies than elective repeat caesarean section.[28]

Adhesions

There are several steps that can be taken during abdominal or pelvic surgery to minimize postoperative complications, such as the formation of adhesions. Such techniques and principles may include:

- Handling all tissue with absolute care

- Using powder-free surgical gloves

- Controlling bleeding

- Choosing sutures and implants carefully

- Keeping tissue moist

- Preventing infection with antibiotics given intravenously to the mother before skin incision

Despite these proactive measures, adhesion formation is a recognized complication of any abdominal or pelvic surgery. To prevent adhesions from forming after caesarean section, adhesion barrier can be placed during surgery to minimize the risk of adhesions between the uterus and ovaries, the small bowel, and almost any tissue in the abdomen or pelvis. This is not current UK practice, as there is no compelling evidence to support the benefit of this intervention.

Adhesions can cause long-term problems, such as:

- Infertility, which may end when adhesions distort the tissues of the ovaries and tubes, impeding the normal passage of the egg (ovum) from the ovary to the uterus. One in five infertility cases may be adhesion related (stoval)

- Chronic pelvic pain, which may result when adhesions are present in the pelvis. Almost 50% of chronic pelvic pain cases are estimated to be adhesion related (stoval)

- Small bowel obstruction: the disruption of normal bowel flow, which can result when adhesions twist or pull the small bowel.

The risk of adhesion formation is one reason why vaginal delivery is usually considered safer than elective caesarean section where there is no medical indication for section for either maternal or fetal reasons.

Child

Non-medically indicated (elective) childbirth before 39 weeks gestation "carry significant risks for the baby with no known benefit to the mother." Newborn mortality at 37 weeks may be up to 3 times the number at 40 weeks, and is elevated compared to 38 weeks gestation. These early term births were associated with more death during infancy, compared to those occurring at 39 to 41 weeks (full term).[29] Researchers in one study and another review found many benefits to going full term, but no adverse effects in the health of the mothers or babies.[29][30]

The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and medical policy makers review research studies and find more incidence of suspected or proven sepsis, RDS, hypoglycemia, need for respiratory support, need for NICU admission, and need for hospitalization > 4–5 days. In the case of caesarean sections, rates of respiratory death were 14 times higher in pre-labor at 37 compared with 40 weeks gestation, and 8.2 times higher for pre-labor caesarean at 38 weeks. In this review, no studies found decreased neonatal morbidity due to non-medically indicated (elective) delivery before 39 weeks.[29]

For otherwise healthy twin pregnancies where both twins are head down a trial of vaginal delivery is recommended at between 37 and 38 weeks.[31][32] Vaginal delivery, in this case, does not worsen the outcome for either infant as compared with caesarean section.[32] There is some controversy on the best method of delivery where the first twin is head first and the second is not, but most obstetricians will recommend normal delivery unless there are other reasons to avoid vaginal birth.[32] When the first twin is not head down, a caesarean section is often recommended.[32] Regardless of whether the twins are delivered by section or vaginally, the medical literature recommends delivery of dichorionic twins at 38 weeks, and monochorionic twins (identical twins sharing a placenta) by 37 weeks due to the increased risk of stillbirth in monochorionic twins who remain in utero after 37 weeks.[33][34] The consensus is that late preterm delivery of monochorionic twins is justified because the risk of stillbirth for post-37-week delivery is significantly higher than the risks posed by delivering monochorionic twins near term (i.e., 36–37 weeks).[35] The consensus concerning monoamniotic twins (identical twins sharing an amniotic sac), the highest risk type of twins, is that they should be delivered by caesarean section at or shortly after 32 weeks, since the risks of intrauterine death of one or both twins is higher after this gestation than the risk of complications of prematurity.[36][37][38]

In a research study widely publicized, singleton children born earlier than 39 weeks may have developmental problems, including slower learning in reading and math.[39]

Other risks include:

- Wet lung (Transient Tachypnea of the Newborn): Failure to pass through the birth canal does not expose the baby to cortisol and epinephrine which typically would reverse the potassium/sodium pumps in the baby's lung. This causes fluid to remain in the lung.[40]

- Potential for early delivery and complications: Preterm delivery may be inadvertently carried out if the due-date calculation is inaccurate. One study found an increased complication risk if a repeat elective caesarean section is performed even a few days before the recommended 39 weeks.[41]

- Higher infant mortality risk: In caesarean sections performed with no indicated medical risk (singleton at full term in a head-down position with no other obstetric or medical complications), the risk of death in the first 28 days of life has been cited as 1.77 per 1,000 live births among women who had caesarean sections, compared to 0.62 per 1,000 for women who delivered vaginally.[42]

Birth by caesarean section also seems to be associated with worse health outcomes later in life, including overweight or obesity, problems in the immune system, and poor digestive system.[43][44] However, caesarean deliveries are found to not affect a newborn's risk of developing food allergy.[45] This finding contradicts a previous study that claims babies born via caesarean section have lower levels of Bacteroides that is linked to peanut allergy in infants.[46]

Classification

Caesarean sections have been classified in various ways by different perspectives.[47] One way to discuss all classification systems is to group them by their focus either on the urgency of the procedure (most common), characteristics of the mother, or as a group based on other, less commonly discussed factors.[47]

By urgency

Conventionally, caesarean sections are classified as being either an elective surgery or an emergency operation.[48] Classification is used to help communication between the obstetric, midwifery and anaesthetic team for discussion of the most appropriate method of anaesthesia. The decision whether to perform general anesthesia or regional anesthesia (spinal or epidural anaesthetic) is important and is based on many indications, including how urgent the delivery needs to be as well as the medical and obstetric history of the woman.[48] Regional anaesthetic is almost always safer for the woman and the baby but sometimes general anaesthetic is safer for one or both, and the classification of urgency of the delivery is an important issue affecting this decision.

A planned caesarean (or elective/scheduled caesarean), arranged ahead of time, is most commonly arranged for medical indications which have developed before or during the pregnancy, and ideally after 39 weeks of gestation. In the UK, this is classified as a 'grade 4' section (delivery timed to suit the mother or hospital staff) or as a 'grade 3' section (no maternal or fetal compromise but early delivery needed). Emergency caesarean sections are performed in pregnancies in which a vaginal delivery was planned initially, but an indication for caesarean delivery has since developed. In the UK they are further classified as grade 2 (delivery required within 90 minutes of the decision but no immediate threat to the life of the woman or the fetus) or grade 1 (delivery required within 30 minutes of the decision: immediate threat to the life of the mother or the baby or both.)[49]

Elective caesarean sections may be performed on the basis of an obstetrical or medical indication, or because of a medically non-indicated maternal request.[31] Among women in the United Kingdom, Sweden and Australia, about 7% preferred caesarean section as a method of delivery.[31] In cases without medical indications the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the UK Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists recommend a planned vaginal delivery.[50] The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends that if after a woman has been provided information on the risk of a planned caesarean section and she still insists on the procedure it should be provided.[31] If provided this should be done at 39 weeks of gestation or later.[50] There is no evidence that ECS can reduce mother-to-child hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus transmission.[51][52][53][54][55]

Caesarean delivery on maternal request

Caesarean delivery on maternal request (CDMR) is a medically unnecessary caesarean section, where the conduct of a childbirth via a caesarean section is requested by the pregnant patient even though there is not a medical indication to have the surgery.[56] Systematic reviews have found no strong evidence about the impact of caesareans for nonmedical reasons.[31][57] Recommendations encourage counseling to identify the reasons for the request, addressing anxieties and information, and encouraging vaginal birth.[31][58] Elective caesareans at 38 weeks in some studies showed increased health complications in the newborn. For this reason ACOG and NICE recommend that elective caesarean sections should not be scheduled before 39 weeks gestation unless there is a medical reason.[59][60][61] Planned caesarean sections may be scheduled earlier if there is a medical reason.[60]

After previous caesarean

Mothers who have previously had a caesarean section are more likely to have a caesarean section for future pregnancies than mothers who have never had a caesarean section. There is discussion about the circumstances under which women should have a vaginal birth after a previous caesarean.

Vaginal birth after caesarean (VBAC) is the practice of birthing a baby vaginally after a previous baby has been delivered by caesarean section (surgically).[62] According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), successful VBAC is associated with decreased maternal morbidity and a decreased risk of complications in future pregnancies.[63] According to the American Pregnancy Association, 90% of women who have undergone caesarean deliveries are candidates for VBAC.[26] Approximately 60–80% of women opting for VBAC will successfully give birth vaginally, which is comparable to the overall vaginal delivery rate in the United States in 2010.[26][27][64]

Twins

For otherwise healthy twin pregnancies where both twins are head down a trial of vaginal delivery is recommended at between 37 and 38 weeks.[31][32] Vaginal delivery in this case does not worsen the outcome for either infant as compared with caesarean section.[32] There is controversy on the best method of delivery where the first twin is head first and the second is not.[32] When the first twin is not head down at the point of labor starting, a caesarean section should be recommended.[32] Although the second twin typically has a higher frequency of problems, it is not known if a planned caesarean section affects this.[31] It is estimated that 75% of twin pregnancies in the United States were delivered by caesarean section in 2008.[65]

Breech birth

A breech birth is the birth of a baby from a breech presentation, in which the baby exits the pelvis with the buttocks or feet first as opposed to the normal head-first presentation. In breech presentation, fetal heart sounds are heard just above the umbilicus.

Babies are usually born head first. If the baby is in another position the birth may be complicated. In a 'breech presentation', the unborn baby is bottom-down instead of head-down. Babies born bottom-first are more likely to be harmed during a normal (vaginal) birth than those born head-first. For instance, the baby might not get enough oxygen during the birth. Having a planned caesarean may reduce these problems. A review looking at planned caesarean section for singleton breech presentation with planned vaginal birth, concludes that in the short term, births with a planned caesarean were safer for babies than vaginal births. Fewer babies died or were seriously hurt when they were born by caesarean. There was tentative evidence that children who were born by caesarean had more health problems at age two. Caesareans caused some short-term problems for mothers such as more abdominal pain. They also had some benefits, such as less urinary incontinence and less perineal pain.[66]

The bottom-down position presents some hazards to the baby during the process of birth, and the mode of delivery (vaginal versus caesarean) is controversial in the fields of obstetrics and midwifery.

Though vaginal birth is possible for the breech baby, certain fetal and maternal factors influence the safety of vaginal breech birth. The majority of breech babies born in the United States and the UK are delivered by caesarean section as studies have shown increased risks of morbidity and mortality for vaginal breech delivery, and most obstetricians counsel against planned vaginal breech birth for this reason. As a result of reduced numbers of actual vaginal breech deliveries, obstetricians and midwives are at risk of de-skilling in this important skill. All those involved in delivery of obstetric and midwifery care in the UK undergo mandatory training in conducting breech deliveries in the simulation environment (using dummy pelvises and mannequins to allow practice of this important skill) and this training is carried out regularly to keep skills up to date.

Resuscitative hysterotomy

A resuscitative hysterotomy, also known as a peri-mortem caesarean delivery, is an emergency caesarean delivery carried out where maternal cardiac arrest has occurred, to assist in resuscitation of the mother by removing the aortocaval compression generated by the gravid uterus. Unlike other forms of caesarean section, the welfare of the fetus is a secondary priority only, and the procedure may be performed even prior to the limit of fetal viability if it is judged to be of benefit to the mother.

Other ways, including the surgery technique

There are several types of caesarean section (CS). An important distinction lies in the type of incision (longitudinal or transverse) made on the uterus, apart from the incision on the skin: the vast majority of skin incisions are a transverse suprapubic approach known as a Pfannenstiel incision but there is no way of knowing from the skin scar which way the uterine incision was conducted.

- The classical caesarean section involves a longitudinal midline incision on the uterus which allows a larger space to deliver the baby. It is performed at very early gestations where the lower segment of the uterus is unformed as it is safer in this situation for the baby: but it is rarely performed other than at these early gestations, as the operation is more prone to complications than a low transverse uterine incision. Any woman who has had a classical section will be recommended to have an elective repeat section in subsequent pregnancies as the vertical incision is much more likely to rupture in labor than the transverse incision.

- The lower uterine segment section is the procedure most commonly used today; it involves a transverse cut just above the edge of the bladder. It results in less blood loss and has fewer early and late complications for the mother, as well as allowing her to consider a vaginal birth in the next pregnancy.

- A caesarean hysterectomy consists of a caesarean section followed by the removal of the uterus. This may be done in cases of intractable bleeding or when the placenta cannot be separated from the uterus.

The EXIT procedure is a specialized surgical delivery procedure used to deliver babies who have airway compression.

The Misgav Ladach method is a modified caesarean section which has been used nearly all over the world since the 1990s. It was described by Michael Stark, the president of the New European Surgical Academy, at the time he was the director of Misgav Ladach, a general hospital in Jerusalem. The method was presented during a FIGO conference in Montréal in 1994[67] and then distributed by the University of Uppsala, Sweden, in more than 100 countries. This method is based on minimalistic principles. He examined all steps in caesarean sections in use, analyzed them for their necessity and, if found necessary, for their optimal way of performance. For the abdominal incision he used the modified Joel Cohen incision and compared the longitudinal abdominal structures to strings on musical instruments. As blood vessels and muscles have lateral sway, it is possible to stretch rather than cut them. The peritoneum is opened by repeat stretching, no abdominal swabs are used, the uterus is closed in one layer with a big needle to reduce the amount of foreign body as much as possible, the peritoneal layers remain unsutured and the abdomen is closed with two layers only. Women undergoing this operation recover quickly and can look after the newborns soon after surgery. There are many publications showing the advantages over traditional caesarean section methods. There is also an increased risk of abruptio placentae and uterine rupture in subsequent pregnancies for women who underwent this method in prior deliveries.[68][69]

Since 2015, the World Health Organization has endorsed the Robson classification as a holistic means of comparing childbirth rates between different settings, with a view to allowing more accurate comparison of caesarean section rates.[70]

Technique

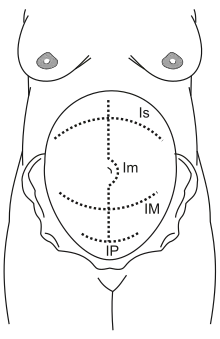

Is: supra-umbilical incision

Im: median incision

IM: Maylard incision

IP: Pfannenstiel incision

Antibiotic prophylaxis is used before an incision.[71] The uterus is incised, and this incision is extended with blunt pressure along a cephalad-caudad axis.[71] The infant is delivered, and the placenta is then removed.[71] The surgeon then makes a decision about uterine exteriorization.[71] Single-layer uterine closure is used when the mother does not want a future pregnancy.[71] When subcutaneous tissue is 2 cm thick or more, surgical suture is used.[71] Discouraged practices include manual cervical dilation, any subcutaneous drain,[72] or supplemental oxygen therapy with intent to prevent infection.[71]

Caesarean section can be performed with single or double layer suturing of the uterine incision.[73] Single layer closure compared with double layer closure has been observed to result in reduced blood loss during the surgery. It is uncertain whether this is the direct effect of the suturing technique or if other factors such as the type and site of abdominal incision contribute to reduced blood loss.[74] Standard procedure includes the closure of the peritoneum. Research questions whether this is needed, with some studies indicating peritoneal closure is associated with longer operative time and hospital stay.[75] The Misgave Ladach method is a surgery technical that may have fewer secondary complications and faster healing, due to the insertion into the muscle.[76]

Anesthesia

Both general and regional anaesthesia (spinal, epidural or combined spinal and epidural anaesthesia) are acceptable for use during caesarean section. Evidence does not show a difference between regional anaesthesia and general anaesthesia with respect to major outcomes in the mother or baby.[77] Regional anaesthesia may be preferred as it allows the mother to be awake and interact immediately with her baby.[78] Compared to general anaesthesia, regional anaesthesia is better at preventing persistent postoperative pain 3 to 8 months after caesarean section.[79] Other advantages of regional anesthesia may include the absence of typical risks of general anesthesia: pulmonary aspiration (which has a relatively high incidence in patients undergoing anesthesia in late pregnancy) of gastric contents and esophageal intubation.[77] One trial found no difference in satisfaction when general anaesthesia was compared with either spinal anaesthesia.[77]

Regional anaesthesia is used in 95% of deliveries, with spinal and combined spinal and epidural anaesthesia being the most commonly used regional techniques in scheduled caesarean section.[80] Regional anaesthesia during caesarean section is different from the analgesia (pain relief) used in labor and vaginal delivery. The pain that is experienced because of surgery is greater than that of labor and therefore requires a more intense nerve block.

General anesthesia may be necessary because of specific risks to mother or child. Patients with heavy, uncontrolled bleeding may not tolerate the hemodynamic effects of regional anesthesia. General anesthesia is also preferred in very urgent cases, such as severe fetal distress, when there is no time to perform a regional anesthesia.

Prevention of complications

Postpartum infection is one of the main causes of maternal death and may account for 10% of maternal deaths globally.[81][31][82] A caesarean section greatly increases the risk of infection and associated morbidity, estimated to be between 5 and 20 times as high, and routine use of antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent infections was found by a meta-analysis to substantially reduce the incidence of febrile morbidity.[82] Infection can occur in around 8% of women who have caesareans,[31] largely endometritis, urinary tract infections and wound infections. The use of preventative antibiotics in women undergoing caesarean section decreased wound infection, endometritis, and serious infectious complications by about 65%.[82] Side effects and effect on the baby is unclear.[82]

Women who have caesareans can recognize the signs of fever that indicate the possibility of wound infection.[31] Taking antibiotics before skin incision rather than after cord clamping reduces the risk for the mother, without increasing adverse effects for the baby.[31][83] Moderate certainty evidence suggest that chlorhexidine gluconate as a skin preparation is slightly more effective in prevention surgical site infections than povodone iodine but further research is needed.[84]

Some doctors believe that during a caesarean section, mechanical cervical dilation with a finger or forceps will prevent the obstruction of blood and lochia drainage, and thereby benefit the mother by reducing the risk of death. The evidence as of 2018 neither supported nor refuted this practice for reducing postoperative morbidity, pending further large studies.[85]

Hypotension (low blood pressure) is common in women who have spinal anaesthesia; intravenous fluids such as crystalloids, or compressing the legs with bandages, stockings, or inflatable devices may help to reduce the risk of hypotension but the evidence is still uncertain about their effectiveness.[86]

Skin-to-skin contact

The WHO and UNICEF recommend that infants born by Caesarean section should have skin-to-skin contact (SSC) as soon as the mother is alert and responsive. Immediate SSC following a spinal or epidural anesthetic is possible because the mother remains alert however, after a general anesthetic the father or other family member may provide SSC until the mother is able.[87]

It is known that during the hours of labor before a vaginal birth a woman's body begins to produce oxytocin which aids in the bonding process, and it is thought that SSC can trigger its production as well. Indeed, women have reported that they felt that SSC had helped them to feel close to and bond with their infant. A review of literature also found that immediate or early SSC increased the likelihood of successful breastfeeding and that newborns were found to cry less and relax quicker when they had SSC with their father as well.[87]

Recovery

It is common for women who undergo caesarean section to have reduced or absent bowel movements for hours to days. During this time, women may experience abdominal cramps, nausea and vomiting. This usually resolves without treatment.[88] Poorly controlled pain following non-emergent caesarean section occurs in between 13% to 78% of women.[89] Following caesarean delivery, complementary and alternative therapies (e.g., acupuncture) may help to relieve pain, though evidence supporting the efficacy of such treatments is extremely limited.[90] Abdominal, wound and back pain can continue for months after a caesarean section. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can be helpful.[31] For the first couple of weeks after a caesarean, women should avoid lifting anything heavier than their baby. To minimize pain during breastfeeding, women should experiment with different breastfeeding holds including the football hold and side-lying hold.[91] Women who have had a caesarean are more likely to experience pain that interferes with their usual activities than women who have vaginal births, although by six months there is generally no longer a difference.[92] Pain during sexual intercourse is less likely than after vaginal birth; by six months there is no difference.[31]

There may be a somewhat higher incidence of postnatal depression in the first weeks after childbirth for women who have caesarean sections, but this difference does not persist.[31] Some women who have had caesarean sections, especially emergency caesareans, experience post-traumatic stress disorder.[31]

Those who undergoes caesarean section has 18.3% chance of chronic surgical pain at three months and 6.8% chance of surgical pain at 12 months.[93]

Frequency

Global rates of caesarean section are increasing.[21] It doubled from 2003 to 2018 to reach 21%, and is increasing annually by 4%. In southern Africa it is less than 5%; while the rate is almost 60% in some parts of Latin America.[94] The Canadian rate was 26% in 2005–2006.[95] Australia has a high caesarean section rate, at 31% in 2007.[96] At one time a rate of 10% to 15% was thought to be ideal;[4] a rate of 19% may result in better outcomes.[8] The World Health Organization officially withdrew its previous recommendation of a 15% C-section rate in June 2010. Their official statement read, "There is no empirical evidence for an optimum percentage. What matters most is that all women who need caesarean sections receive them."[97]

More than 50 nations have rates greater than 27%. Another 45 countries have rates less than 7.5%.[8] There are efforts to both improve access to and reduce the use of C-section.[8] Globally, 1% of all caesarean deliveries are carried out without medical need. Overall, the caesarean section rate was 25.7% for 2004–2008.[98][99]

There is no significant difference in caesarean rates when comparing midwife continuity care to conventional fragmented care.[100] More emergency caesareans—about 66%—are performed during the day rather than the night.[101]

The rate has risen to 46% in China and to levels of 25% and above in many Asian, European and Latin American countries.[102] In Brazil and Iran the caesarean section rate is greater than 40%.[103] Brazil has one of the highest caesarean section rates in the world, with rates in the public sector of 35–45%, and 80–90% in the private sector.[104]

Europe

Across Europe, there are differences between countries: in Italy the caesarean section rate is 40%, while in the Nordic countries it is 14%.[105] In the United Kingdom, in 2008, the rate was 24%.[106] In Ireland the rate was 26.1% in 2009.[107]

In Italy, the incidence of caesarean sections is particularly high, although it varies from region to region.[108] In Campania, 60% of 2008 births reportedly occurred via caesarean sections.[109] In the Rome region, the mean incidence is around 44%, but can reach as high as 85% in some private clinics.[110][111]

United States

In the United States the rate of C-section is around 33%, varying from 23% to 40% depending on the state.[3] One of three women who gave birth in the US delivered by caesarean in 2011. In 2012, close to 23 million C-sections were carried out globally.[8]

With nearly 1.3 million stays, caesarean section was one of the most common procedures performed in U.S. hospitals in 2011. It was the second-most common procedure performed for people ages 18 to 44 years old.[112] Caesarean rates in the U.S. have risen considerably since 1996.[113] The rate has increased in the United States, to 33% of all births in 2012, up from 21% in 1996.[3] In 2010, the caesarean delivery rate was 32.8% of all births (a slight decrease from 2009's high of 32.9% of all births).[114] A study found that in 2011, women covered by private insurance were 11% more likely to have a caesarean section delivery than those covered by Medicaid.[115] The increase in use has not resulted in improved outcomes, resulting in the position that C-sections may be done too frequently.[3]

History

Historically, caesarean sections performed upon a live woman usually resulted in the death of the mother.[116] It was considered an extreme measure, performed only when the mother was already dead or considered to be beyond help. By way of comparison, see the resuscitative hysterotomy or perimortem caesarean section.

According to the ancient Chinese Records of the Grand Historian, Luzhong, a sixth-generation descendant of the mythical Yellow Emperor, had six sons, all born by "cutting open the body". The sixth son Jilian founded the House of Mi that ruled the State of Chu (c. 1030–223 BC).[117]

The mother of Bindusara (born c. 320 BC, ruled 298 – c. 272 BC), the second Mauryan Samrat (emperor) of India, accidentally consumed poison and died when she was close to delivering him. Chanakya, Chandragupta's teacher and adviser, made up his mind that the baby should survive. He cut open the belly of the queen and took out the baby, thus saving the baby's life.[118]

An early account of caesarean section in Iran (Persia) is mentioned in the book of Shahnameh, written around 1000 AD, and relates to the birth of Rostam, the legendary hero of that country.[119][120] According to the Shahnameh, the Simurgh instructed Zal upon how to perform a caesarean section, thus saving Rudaba and the child Rostam. In Persian literature caeserean section is known as Rostamina (رستمینه).[121]

In the Irish mythological text the Ulster Cycle, the character Furbaide Ferbend is said to have been born by posthumous caesarean section, after his mother was murdered by his evil aunt Medb.

The Babylonian Talmud, an ancient Jewish religious text, mentions a procedure similar to the caesarean section. The procedure is termed yotzei dofen. It also discusses at length the permissibility of performing a c-section on a dying or dead mother.[118] There is also some basis for supposing that Jewish women regularly survived the operation in Roman times (as early as the 2nd century AD).[122]

Pliny the Elder theorized that Julius Caesar's name came from an ancestor who was born by caesarean section, but the truth of this is debated (see the discussion of the etymology of Caesar). Some stories involve Caesar himself being born from the procedure; this is almost certainly false, as Caesar's mother Aurelia Cotta lived until Caesar's mid-40s. The Ancient Roman caesarean section was first performed to remove a baby from the womb of a mother who died during childbirth, a practice sometimes called the Caesarean law.[123]

The Catalan saint Raymond Nonnatus (1204–1240) received his surname—from the Latin non-natus ("not born")—because he was born by caesarean section. His mother died while giving birth to him.[124]

There is some indirect evidence that the first caesarean section that was survived by both the mother and child was performed in Prague in 1337.[125][126] The mother was Beatrice of Bourbon, the second wife of the King of Bohemia John of Luxembourg. Beatrice gave birth to the king's son Wenceslaus I, later the duke of Luxembourg, Brabant, and Limburg, and who became the half brother of the later King of Bohemia and Holy Roman Emperor, Charles IV.

In an account from the 1580s, Jakob Nufer, a veterinarian in Siegershausen, Switzerland, is supposed to have performed the operation on his wife after a prolonged labour, with her surviving. His wife allegedly bore five more children, including twins, and the baby delivered by caesarean section purportedly lived to the age of 77.[127][128][129]

For most of the time since the 16th century, the procedure had a high mortality rate. In Great Britain and Ireland, the mortality rate in 1865 was 85%. Key steps in reducing mortality were:

- Introduction of the transverse incision technique to minimize bleeding by Ferdinand Adolf Kehrer in 1881 is thought to be first modern CS performed.

- The introduction of uterine suturing by Max Sänger in 1882

- Modification by Hermann Johannes Pfannenstiel in 1900, see Pfannenstiel incision

- Extraperitoneal CS and then moving to low transverse incision (Krönig, 1912)

- Adherence to principles of asepsis

- Anesthesia advances

- Blood transfusion

- Antibiotics

European travellers in the Great Lakes region of Africa during the 19th century observed caesarean sections being performed on a regular basis.[130] The expectant mother was normally anesthetized with alcohol, and herbal mixtures were used to encourage healing. From the well-developed nature of the procedures employed, European observers concluded they had been employed for some time.[130] Robert William Felkin provided a detailed description.[131][132] James Barry was the first European doctor to carry out a successful caesarean in Africa, while posted to Cape Town between 1817 and 1828.[133]

The first successful caesarean section to be performed in the United States took place in Mason County, Virginia (now Mason County, West Virginia), in 1794. The procedure was performed by Dr. Jesse Bennett on his wife Elizabeth.[134]

Caesarius of Terracina

The patron saint of caesarean section is Caesarius, a young deacon martyred at Terracina, who has replaced and Christianized the pagan figure of Caesar.[135] The martyr (Saint Cesareo in Italian) is invoked for the success of this surgical procedure, because it was considered the new "Christian Caesar" – as opposed to the "pagan Caesar" – in the Middle Ages it began to be invoked by pregnant women to wish a physiological birth, for the success of the expulsion of the baby from the uterus and, therefore, for their salvation and that of the unborn. The practice continues, in fact the martyr Caesarius is invoked by the future mothers who, due to health problems or that of the baby, must give birth to their child by caesarean section.[136]

Etymology

The Roman Lex Regia (royal law), later the Lex Caesarea (imperial law), of Numa Pompilius (715–673 BC),[137] required the child of a mother who had died during childbirth to be cut from her womb.[138] There was a cultural taboo that mothers should not be buried pregnant,[139] that may have reflected a way of saving some fetuses. Roman practice required a living mother to be in her tenth month of pregnancy before resorting to the procedure, reflecting the knowledge that she could not survive the delivery.[140]

Speculations that the Roman dictator Julius Caesar was born by the method now known as C-section are false.[141] Although caesarean sections were performed in Roman times, no classical source records a mother surviving such a delivery.[138][142] As late as the 12th century, scholar and physician Maimonides expresses doubt over the possibility of a woman's surviving this procedure and again becoming pregnant.[143] The term has also been explained as deriving from the verb caedere, "to cut", with children delivered this way referred to as caesones. Pliny the Elder refers to a certain Julius Caesar (an ancestor of the famous Roman statesman) as ab utero caeso, "cut from the womb" giving this as an explanation for the cognomen "Caesar" which was then carried by his descendants.[138] Nonetheless, the false etymology has been widely repeated until recently. For example, the first (1888) and second (1989) editions of the Oxford English Dictionary say that caesarean birth "was done in the case of Julius Cæsar".[144] More recent dictionaries are more diffident: the online edition of the OED (2021) mentions "the traditional belief that Julius Cæsar was delivered this way",[145] and Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary (2003) says "from the legendary association of such a delivery with the Roman cognomen Caesar".[146]

The word 'Caesar', meaning either Julius Caesar or an emperor in general, is also borrowed or calqued in the name of the procedure in many other languages in Europe and beyond.[147]

Finally, the Roman praenomen (given name) Caeso was said to be given to children who were born via C-section. While this was probably just folk etymology made popular by Pliny the Elder, it was well known by the time the term came into common use.[148]

Spelling

The term caesarean is spelled in various accepted ways, as discussed at Wiktionary. The Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) of the United States National Library of Medicine (NLM) uses cesarean section,[149] while some other American medical works, e.g. Saunders Comprehensive Veterinary Dictionary, use caesarean,[150] as do most British works. The online versions of the US-published Merriam-Webster Dictionary[151] and American Heritage Dictionary[150] list cesarean first and other spellings as "variants".

Society and culture

Presence of father

In many hospitals, the mother's partner is encouraged to attend the surgery to support her and share the experience.[152] The anaesthetist will usually lower the drape temporarily as the child is delivered so the parents can see their newborn.

Special cases

In Judaism, there is a dispute among the poskim (Rabbinic authorities) as to whether the first-born son from a caesarean section has the laws of a bechor.[153] Traditionally, a male child delivered by caesarean is not eligible for the Pidyon HaBen dedication ritual.[154][155]

In rare cases, caesarean sections can be used to remove a dead fetus; otherwise, the woman has to labour and deliver a baby known to be a stillbirth. A late-term abortion using caesarean section procedures is termed a hysterotomy abortion and is very rarely performed.[156]

The mother may perform a caesarean section on herself; there have been successful cases, such as Inés Ramírez Pérez of Mexico who, on 5 March 2000, took this action. She survived, as did her son, Orlando Ruiz Ramírez.[157][158][159][160]

References

- Fadhley, Salim (2014). "Caesarean section photography". WikiJournal of Medicine. 1 (2). doi:10.15347/wjm/2014.006.

- "Pregnancy Labor and Birth". Office on Women's Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 1 February 2017. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "Safe Prevention of the Primary Cesarean Delivery". American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. March 2014. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- "WHO Statement on Caesarean Section Rates" (PDF). 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 May 2015. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- Lauwers, Judith; Swisher, Anna (2010). Counseling the Nursing Mother: A Lactation Consultant's Guide. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 274. ISBN 9781449619480. Archived from the original on 11 September 2017.

- American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, archived from the original on 1 September 2013, retrieved 1 August 2013

- Yeniel, AO; Petri, E (January 2014). "Pregnancy, childbirth, and sexual function: perceptions and facts". International Urogynecology Journal. 25 (1): 5–14. doi:10.1007/s00192-013-2118-7. PMID 23812577. S2CID 2638969.

- Molina, G; Weiser, TG; Lipsitz, SR; Esquivel, MM; Uribe-Leitz, T; Azad, T; Shah, N; Semrau, K; Berry, WR; Gawande, AA; Haynes, AB (1 December 2015). "Relationship Between Cesarean Delivery Rate and Maternal and Neonatal Mortality". JAMA. 314 (21): 2263–70. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.15553. PMID 26624825.

- "Births: Provisional Data for 2017" (PDF). CDC. May 2018. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- Moore, Michele C.; Costa, Caroline M. de (2004). Cesarean Section: Understanding and Celebrating Your Baby's Birth. JHU Press. p. Chapter 2. ISBN 9780801881336.

- "The Truth About Julius Caesar and "Caesarean" Sections". 25 October 2013.

- Turner R (1990). "Caesarean Section Rates, Reasons for Operations Vary Between Countries". Family Planning Perspectives. 22 (6): 281–2. doi:10.2307/2135690. JSTOR 2135690.

- "Management of Genital Herpes in Pregnancy". ACOG. May 2020. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- Savage W (2007). "The rising Caesarean section rate: a loss of obstetric skill?". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 27 (4): 339–46. doi:10.1080/01443610701337916. PMID 17654182. S2CID 27545840.

- Domenjoz, I; Kayser, B; Boulvain, M (October 2014). "Effect of physical activity during pregnancy on mode of delivery". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 211 (4): 401.e1–11. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2014.03.030. PMID 24631706.

- McDonagh, Marian; Skelly, Andrea C.; Hermesch, Amy; Tilden, Ellen; Brodt, Erika D.; Dana, Tracy; Ramirez, Shaun; Fu, Rochelle; Kantner, Shelby N. (2021). Cervical Ripening in the Outpatient Setting. AHRQ Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US). PMID 33818996.

- "Caesarean Section". NHS Direct. Archived from the original on 1 February 2009. Retrieved 26 July 2006.

- Liu S, Liston RM, Joseph KS, Heaman M, Sauve R, Kramer MS (2007). "Maternal mortality and severe morbidity associated with low-risk planned cesarean delivery versus planned vaginal delivery at term". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 176 (4): 455–60. doi:10.1503/cmaj.060870. PMC 1800583. PMID 17296957.

- Pai, Madhukar (2000). "Medical Interventions: Caesarean Sections as a Case Study". Economic and Political Weekly. 35 (31): 2755–61.

- "Why are Caesareans Done?". Gynaecworld. Archived from the original on 3 December 2008. Retrieved 26 July 2006.

- Saeed, Khalid B M; Greene, Richard A; Corcoran, Paul; O'Neill, Sinéad M (11 January 2017). "Incidence of surgical site infection following caesarean section: a systematic review and meta-analysis protocol". BMJ Open. 7 (1): e013037. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013037. PMC 5253548. PMID 28077411.

- Silver, Robert M.; Landon, Mark B.; Rouse, Dwight J.; Leveno, Kenneth J.; Spong, Catherine Y.; Thom, Elizabeth A.; Moawad, Atef H.; Caritis, Steve N.; Harper, Margaret; Wapner, Ronald J.; Sorokin, Yoram; Miodovnik, Menachem; Carpenter, Marshall; Peaceman, Alan M.; O'Sullivan, Mary J.; Sibai, Baha; Langer, Oded; Thorp, John M.; Ramin, Susan M.; Mercer, Brian M. (June 2006). "Maternal Morbidity Associated With Multiple Repeat Cesarean Deliveries". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 107 (6): 1226–1232. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000219750.79480.84. PMID 16738145. S2CID 257455.

- Olde E, van der Hart O, Kleber R, van Son M (January 2006). "Post-traumatic stress following childbirth: a review". Clinical Psychology Review. 26 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2005.07.002. hdl:1874/16760. PMID 16176853. S2CID 22137961.

- Gurol-Urganci, I.; Bou-Antoun, S.; Lim, C.P.; Cromwell, D.A.; Mahmood, T.A.; Templeton, A.; van der Meulen, J.H. (July 2013). "Impact of Caesarean section on subsequent fertility: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Human Reproduction. 28 (7): 1943–1952. doi:10.1093/humrep/det130. PMID 23644593.

- "Birth After Previous Caesarean Birth, Green-top Guideline No. 45" (PDF). Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. February 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 December 2014.

- "Vaginal Birth after Cesarean (VBAC)". American Pregnancy Association. Archived from the original on 21 June 2012. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

- Vaginal birth after C-section (VBAC) guide Archived 12 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Mayo Clinic

- American Congress of Obstetricians and, Gynecologists (August 2010). "ACOG Practice bulletin no. 115: Vaginal birth after previous cesarean delivery". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 116 (2 Pt 1): 450–63. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181eeb251. PMID 20664418.

- "Elimination of Non-medically Indicated (Elective) Deliveries Before 39 Weeks Gestational Age" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 November 2012. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- Reddy, Uma M.; Bettegowda, Vani R.; Dias, Todd; Yamada-Kushnir, Tomoko; Ko, Chia-Wen; Willinger, Marian (2011). "Term Pregnancy: A Period of Heterogeneous Risk for Infant Mortality". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 117 (6): 1279–1287. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182179e28. PMC 5485902. PMID 21606738.

- National Collaborating Centre for Women's and Children's Health (UK) (2011). "Caesarean Section: NICE Clinical Guidelines, No. 132". National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: Guidance. National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence. PMID 23285498. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Biswas, A; Su, LL; Mattar, C (April 2013). "Caesarean section for preterm birth and, breech presentation and twin pregnancies". Best Practice & Research: Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 27 (2): 209–19. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2012.09.002. PMID 23062593.

- Lee YM (2012). "Delivery of twins". Seminars in Perinatology. 36 (3): 195–200. doi:10.1053/j.semperi.2012.02.004. PMID 22713501.

- Hack KE, Derks JB, Elias SG, Franx A, Roos EJ, Voerman SK, Bode CL, Koopman-Esseboom C, Visser GH (2008). "Increased perinatal mortality and morbidity in monochorionic versus dichorionic twin pregnancies: clinical implications of a large Dutch cohort study". BJOG. 115 (1): 58–67. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01556.x. PMID 17999692. S2CID 20983040.

- Danon D, Sekar R, Hack KE, Fisk NM (2013). "Increased stillbirth in uncomplicated monochorionic twin pregnancies: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 121 (6): 1318–26. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e318292766b. PMID 23812469. S2CID 5152813.

- Pasquini L, Wimalasundera RC, Fichera A, Barigye O, Chappell L, Fisk NM (2006). "High perinatal survival in monoamniotic twins managed by prophylactic sulindac, intensive ultrasound surveillance, and Cesarean delivery at 32 weeks' gestation". Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 28 (5): 681–7. doi:10.1002/uog.3811. PMID 17001748. S2CID 26098748.

- Murata M, Ishii K, Kamitomo M, Murakoshi T, Takahashi Y, Sekino M, Kiyoshi K, Sago H, Yamamoto R, Kawaguchi H, Mitsuda N (2013). "Perinatal outcome and clinical features of monochorionic monoamniotic twin gestation". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research. 39 (5): 922–5. doi:10.1111/jog.12014. PMID 23510453. S2CID 40347063.

- Baxi LV, Walsh CA (2010). "Monoamniotic twins in contemporary practice: a single-center study of perinatal outcome". Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine. 23 (6): 506–10. doi:10.3109/14767050903214590. PMID 19718582. S2CID 37447326.

- "Academic Achievement Varies With Gestational Age Among Children Born at Term". Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- Jha, Kanishk; Nassar, George N.; Makker, Kartikeya (2022), "Transient Tachypnea of the Newborn", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 30726039, retrieved 22 June 2022

- Study: Early Repeat C-Sections Puts Babies At Risk Archived 31 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Npr.org (8 January 2009). Retrieved on 26 July 2011.

- "High infant mortality rate seen with elective c-section". Reuters Health—September 2006. Medicineonline.com. 14 September 2006. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- Mueller, Noel T.; Zhang, Mingyu; Hoyo, Cathrine; Østbye, Truls; Benjamin-Neelon, Sara E. (August 2019). "Does cesarean delivery impact infant weight gain and adiposity over the first year of life?". International Journal of Obesity. 43 (8): 1549–1555. doi:10.1038/s41366-018-0239-2. ISSN 1476-5497. PMC 6476694. PMID 30349009.

- C. Yuan et al. (2016), "Association Between Cesarean Birth and Risk of Obesity in Offspring in Childhood, Adolescence, and Early Adulthood", JAMA Pediatrics.

- Currell, Anne; Koplin, Jennifer J.; Lowe, Adrian J.; Perrett, Kirsten P.; Ponsonby, Anne-Louise; Tang, Mimi L. K.; Dharmage, Shyamali C.; Peters, Rachel L. (18 May 2022). "Mode of Birth Is Not Associated With Food Allergy Risk in Infants". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice. 10 (8): 2135–2143.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2022.03.031. ISSN 2213-2198. PMID 35597762. S2CID 248903112.

- "Why C-Section Babies May Be at Higher Risk for a Food Allergy". Consumer Health News | HealthDay. 30 April 2021. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- Torloni, Maria Regina; Betran, Ana Pilar; Souza, Joao Paulo; Widmer, Mariana; Allen, Tomas; Gulmezoglu, Metin; Merialdi, Mario; Althabe, Fernando (20 January 2011). "Classifications for Cesarean Section: A Systematic Review". PLOS One. 6 (1): e14566. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...614566T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0014566. PMC 3024323. PMID 21283801.

- Lucas, DN; Yentis, SM; Kinsella, SM; Holdcroft, A; May, AE; Wee, M; Robinson, PN (July 2000). "Urgency of caesarean section: a new classification". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 93 (7): 346–50. doi:10.1177/014107680009300703. PMC 1298057. PMID 10928020.

- Miheso, Johnstone; Burns, Sean. "Care of women undergoing emergency caesarean section" (PDF). NHS Choices. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 March 2018. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- American College of Obstetricians and, Gynecologists (April 2013). "ACOG committee opinion no. 559: Cesarean delivery on maternal request". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 121 (4): 904–7. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000428647.67925.d3. PMID 23635708.

- Yang, Jin; Zeng, Xue-mei; Men, Ya-lin; Zhao, Lian-san (2008). "Elective caesarean section versus vaginal delivery for preventing mother to child transmission of hepatitis B virus – a systematic review". Virology Journal. 5 (1): 100. doi:10.1186/1743-422X-5-100. PMC 2535601. PMID 18755018.

- Borgia, Guglielmo (2012). "Hepatitis B in pregnancy". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 18 (34): 4677–83. doi:10.3748/wjg.v18.i34.4677. PMC 3442205. PMID 23002336.

- Hu, Yali; Chen, Jie; Wen, Jian; Xu, Chenyu; Zhang, Shu; Xu, Biyun; Zhou, Yi-Hua (24 May 2013). "Effect of elective cesarean section on the risk of mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis B virus". BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 13 (1): 119. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-13-119. PMC 3664615. PMID 23706093.

- McIntyre, Paul G; Tosh, Karen; McGuire, William (18 October 2006). "Caesarean section versus vaginal delivery for preventing mother to infant hepatitis C virus transmission". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010 (4): CD005546. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005546.pub2. PMC 8895451. PMID 17054264.

- European Paediatric Hepatitis C Virus Network (December 2005). "A Significant Sex—but Not Elective Cesarean Section—Effect on Mother‐to‐Child Transmission of Hepatitis C Virus Infection". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 192 (11): 1872–1879. doi:10.1086/497695. PMID 16267757.

- NIH (2006). "State-of-the-Science Conference Statement. Cesarean Delivery on Maternal Request" (PDF). Obstetrics & Gynecology. 107 (6): 1386–97. doi:10.1097/00006250-200606000-00027. PMID 16738168. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 30 December 2008.

- Lavender, T; Hofmeyr, GJ; Neilson, JP; Kingdon, C; Gyte, GM (14 March 2012). "Caesarean section for non-medical reasons at term". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3 (3): CD004660. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004660.pub3. PMC 4171389. PMID 22419296.

- "Elective Surgery and Patient Choice – ACOG". Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 4 October 2015.

- Glavind, Julie; Uldbjerg, Niels (April 2015). "Elective cesarean delivery at 38 and 39 weeks". Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 27 (2): 121–127. doi:10.1097/gco.0000000000000158. PMID 25689238. S2CID 32050828.

- "Caesarean section | Guidance and guidelines | NICE". www.nice.org.uk. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- "Committee Opinion No. 559". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 121 (4): 904–907. April 2013. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000428647.67925.d3. PMID 23635708.

- Vaginal Birth After Cesarean (VBAC) – Overview Archived 30 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine, WebMD

- American College of Obstetricians and, Gynecologists (August 2010). "ACOG Practice bulletin no. 115: Vaginal birth after previous cesarean delivery". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 116 (2 Pt 1): 450–63. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181eeb251. PMID 20664418.

- "NCHS Data Brief: Recent Trends in Cesarean Delivery in the United States Products". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. March 2010. Archived from the original on 17 May 2012. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

- Lee HC, Gould JB, Boscardin WJ, El-Sayed YY, Blumenfeld YJ (2011). "Trends in cesarean delivery for twin births in the United States: 1995–2008". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 118 (5): 1095–101. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182318651. PMC 3202294. PMID 22015878.

- Hofmeyr, G Justus; Hannah, Mary; Lawrie, Theresa A (21 July 2015). "Planned caesarean section for term breech delivery". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (7): CD000166. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000166.pub2. PMC 6505736. PMID 26196961.

- Stark M. Technique of cesarean section: Misgav Ladach method. In: Popkin DR, Peddle LJ (eds): Women's Health Today. Perspectives on current research and clinical practice. Proceedings of the XIV World Congress of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, Montreal. Parthenon Publishing group, New York, 81–5

- Nabhan AF (2008). "Long-term outcomes of two different surgical techniques for cesarean". International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 100 (1): 69–75. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.07.011. PMID 17904561. S2CID 5847957.

- Hudić I, Bujold E, Fatušić Z, Skokić F, Latifagić A, Kapidžić M, Fatušić J (2012). "The Misgav-Ladach method of cesarean section: a step forward in operative technique in obstetrics". Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 286 (5): 1141–6. doi:10.1007/s00404-012-2448-6. PMID 22752598. S2CID 809690.

- World Health Organization Human Reproduction Programme, 10 April 2015 (2015). "WHO Statement on caesarean section rates". Reprod Health Matters. 23 (45): 149–50. doi:10.1016/j.rhm.2015.07.007. hdl:11343/249912. PMID 26278843. S2CID 40829330.

- Dahlke, Joshua D.; Mendez-Figueroa, Hector; Rouse, Dwight J.; Berghella, Vincenzo; Baxter, Jason K.; Chauhan, Suneet P. (October 2013). "Evidence-based surgery for cesarean delivery: an updated systematic review". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 209 (4): 294–306. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2013.02.043. PMID 23467047.

- Gates, Simon; Anderson, Elizabeth R. (13 December 2013). "Wound drainage for caesarean section". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12): CD004549. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004549.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 24338262.

- Stark M, Chavkin Y, Kupfersztain C, Guedj P, Finkel AR (March 1995). "Evaluation of combinations of procedures in cesarean section". International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 48 (3): 273–6. doi:10.1016/0020-7292(94)02306-J. PMID 7781869. S2CID 72559269.

- Dodd, Jodie M; Anderson, Elizabeth R; Gates, Simon; Grivell, Rosalie M (22 July 2014). "Surgical techniques for uterine incision and uterine closure at the time of caesarean section". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (7): CD004732. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004732.pub3. PMID 25048608.

- Bamigboye, AA; Hofmeyr, GJ (11 August 2014). "Closure versus non-closure of the peritoneum at caesarean section: short- and long-term outcomes". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 8 (8): CD000163. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000163.pub2. PMC 4448220. PMID 25110856.

- Holmgren, G; Sjöholm, L; Stark, M (August 1999). "The Misgav Ladach method for cesarean section: method description". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 78 (7): 615–21. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0412.1999.780709.x. PMID 10422908. S2CID 25845500.

- Afolabi BB, Lesi FE (2012). "Regional versus general anaesthesia for Caesarean section". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10: CD004350. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004350.pub3. PMID 23076903.

- Hawkins JL, Koonin LM, Palmer SK, Gibbs CP (1997). "Anesthesia-related deaths during obstetric delivery in the United States, 1979–1990". Anesthesiology. 86 (2): 277–84. doi:10.1097/00000542-199702000-00002. PMID 9054245. S2CID 21467445.

- Weinstein, Erica J; Levene, Jacob L; Cohen, Marc S; Andreae, Doerthe A; Chao, Jerry Y; Johnson, Matthew; Hall, Charles B; Andreae, Michael H (21 June 2018). "Local anaesthetics and regional anaesthesia versus conventional analgesia for preventing persistent postoperative pain in adults and children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6 (2): CD007105. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007105.pub4. PMC 6377212. PMID 29926477.

- Bucklin BA, Hawkins JL, Anderson JR, Ullrich FA (2005). "Obstetric anesthesia workforce survey: twenty-year update". Anesthesiology. 103 (3): 645–53. doi:10.1097/00000542-200509000-00030. PMID 16129992.

- Kassebaum, NJ; Bertozzi-Villa, A; Coggeshall, MS; Shackelford, KA; Steiner, C; et al. (2 May 2014). "Global, regional, and national levels and causes of maternal mortality during 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". The Lancet. 384 (9947): 980–1004. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60696-6. PMC 4255481. PMID 24797575.

- Smaill, Fiona M; Grivell, Rosalie M (28 October 2014). "Antibiotic prophylaxis versus no prophylaxis for preventing infection after cesarean section". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (10): CD007482. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007482.pub3. PMC 4007637. PMID 25350672.

- Mackeen, A. Dhanya; Packard, Roger E; Ota, Erika; Berghella, Vincenzo; Baxter, Jason K; Mackeen, A. Dhanya (2014). "Timing of intravenous prophylactic antibiotics for preventing postpartum infectious morbidity in women undergoing cesarean delivery". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12): CD009516. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009516.pub2. PMID 25479008.

- Hadiati, Diah R.; Hakimi, Mohammad; Nurdiati, Detty S.; Masuzawa, Yuko; da Silva Lopes, Katharina; Ota, Erika (25 June 2020). "Skin preparation for preventing infection following caesarean section". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (6): CD007462. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007462.pub5. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 7386833. PMID 32580252.

- Liabsuetrakul, Tippawan; Peeyananjarassri, Krantarat (10 August 2018). "Mechanical dilatation of the cervix during elective caesarean section before the onset of labour for reducing postoperative morbidity". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 8 (11): CD008019. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008019.pub3. PMC 6513223. PMID 30096215.

- Chooi, C; Cox, JJ; Lumb, RS; Middleton, P; Chemali, M; Emmett, RS; Simmons, SW; Cyna, AM (1 July 2020). "Techniques for preventing hypotension during spinal anaesthesia for caesarean section". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (7): CD002251. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002251.pub4. PMC 7387232. PMID 32619039.

- Stevens, J.; Schmied, V.; Burns, E.; Dahlen, H. (2014). "Immediate or early skin‐to‐skin contact after a Caesarean section: a review of the literature". Maternal & Child Nutrition. 10 (4): 456–473. doi:10.1111/mcn.12128. PMC 6860199. PMID 24720501.

- Pereira Gomes Morais, Edna; Riera, Rachel; Porfírio, Gustavo JM; Macedo, Cristiane R; Sarmento Vasconcelos, Vivian; de Souza Pedrosa, Alexsandra; Torloni, Maria R (17 October 2016). "Chewing gum for enhancing early recovery of bowel function after caesarean section". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (10): CD011562. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011562.pub2. PMC 6472604. PMID 27747876.

- Yang, Michael M H; Hartley, Rebecca L; Leung, Alexander A; Ronksley, Paul E; Jetté, Nathalie; Casha, Steven; Riva-Cambrin, Jay (1 April 2019). "Preoperative predictors of poor acute postoperative pain control: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ Open. 9 (4): e025091. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025091. PMC 6500309. PMID 30940757.

- Zimpel, SA; Torloni, MR; Porfírio, GJ; Flumignan, RL; da Silva, EM (1 September 2020). "Complementary and alternative therapies for post-caesarean pain". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9: CD011216. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011216.pub2. PMID 32871021. S2CID 221466152.

- "C-section recovery: What to expect". Mayo Clinic.

- Lydon-Rochelle, MT; Holt, VL; Martin, DP (July 2001). "Delivery method and self-reported postpartum general health status among primiparous women". Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 15 (3): 232–40. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3016.2001.00345.x. PMID 11489150.

- Jin J, Peng L, Chen Q, Zhang D, Ren L, Qin P, Min S (October 2016). "Prevalence and risk factors for chronic pain following cesarean section: a prospective study". BMC Anesthesiology. 16 (1): 99. doi:10.1186/s12871-016-0270-6. PMC 5069795. PMID 27756207.

- "Stemming the global caesarean section epidemic". The Lancet. 13 October 2018. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- "C-section rate in Canada continues upward trend". Canada.com. 26 July 2007. Archived from the original on 14 May 2014.

- "To push or not to push? It's a woman's right to decide". The Sydney Morning Herald. 2 January 2011. Archived from the original on 30 August 2011.

- "Should there be a limit on Caesareans?". BBC News. 30 June 2010. Archived from the original on 20 July 2010.

- "WHO | Global survey on maternal and perinatal health". Archived from the original on 10 November 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- Souza, JP; Gülmezoglu, AM; Lumbiganon, P; Laopaiboon, M; Carroli, G; Fawole, B; Ruyan, P (10 November 2010). "Caesarean section without medical indications is associated with an increased risk of adverse short-term maternal outcomes: the 2004–2008 WHO Global Survey on Maternal and Perinatal Health". BMC Medicine. 8 (1): 71. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-8-71. PMC 2993644. PMID 21067593.

- Hodnett ED; Hodnett, Ellen (2000). Hodnett, Ellen (ed.). "Continuity of caregivers for care during pregnancy and childbirth". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD000062. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000062. PMID 10796108.

Hodnett ED; Henderson, Sonja (2008). Henderson, Sonja (ed.). "WITHDRAWN: Continuity of caregivers for care during pregnancy and childbirth". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD000062. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000062.pub2. PMID 18843605. - Goldstick O, Weissman A, Drugan A (2003). "The circadian rhythm of "urgent" operative deliveries". Israel Medical Association Journal. 5 (8): 564–6. PMID 12929294.

- "C-section rates around globe at 'epidemic' levels". AP / NBC News. 12 January 2010. Archived from the original on 16 March 2013. Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- "More evidence for a link between Caesarean sections and obesity". The Economist. 11 October 2017.

- Ramires de Jesus, G; Ramires de Jesus, N; Peixoto-Filho, FM; Lobato, G (April 2015). "Caesarean rates in Brazil: what is involved?". BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 122 (5): 606–9. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.13119. PMID 25327984. S2CID 43551235.

- "Women can choose Caesarean birth". BBC News. 23 November 2011. Archived from the original on 19 August 2012.

- "Focus on: caesarean section—NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement". Institute.nhs.uk. 8 October 2009. Archived from the original on 28 December 2011. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- "Caesarean Section Rates Royal College of Physicians of Ireland". Rcpi.ie. Archived from the original on 2 May 2012.

- "La clinica dei record: 9 neonati su 10 nati con il parto cesareo". Corriere della Sera. 14 January 2009. Archived from the original on 24 July 2009. Retrieved 5 February 2009.

- "Sagliocco denuncia boom di parti cesarei in Campania". Pupia.tv. 31 January 2009. Archived from the original on 18 April 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2009.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 12 August 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Cesarei, alla Mater Dei il record". Tgcom.mediaset.it. 14 January 2009. Retrieved 5 February 2009.

- Pfuntner A., Wier L.M., Stocks C. Most Frequent Procedures Performed in U.S. Hospitals, 2011. HCUP Statistical Brief #165. October 2013. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. "Most Frequent Procedures Performed in U.S. Hospitals, 2011 – Statistical Brief #165". Archived from the original on 24 October 2013. Retrieved 22 October 2013..

- "Births: Preliminary Data for 2007" (PDF). National Center for Health Statistics. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 August 2013. Retrieved 23 November 2006.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 July 2017. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Moore JE, Witt WP, Elixhauser A (April 2014). "Complicating Conditions Associate With Childbirth, by Delivery Method and Payer, 2011". HCUP Statistical Brief #173. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- Shorter, E (1982). A History of Women's Bodies. Basic Books, Inc. Publishers. p. 98. ISBN 0465030297.

- Sima Qian. "楚世家 (House of Chu)". Records of the Grand Historian (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 10 March 2012. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- Lurie S (2005). "The changing motives of cesarean section: from the ancient world to the twenty-first century". Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 271 (4): 281–285. doi:10.1007/s00404-005-0724-4. PMID 15856269. S2CID 26690619.

- Shahbazi, A. Shapur. "RUDABA". Encyclopedia Iranica. Retrieved 19 July 2009.

- Torpin R, Vafaie I (1961). "The birth of Rustam. An early account of cesarean section in Iran". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 81: 185–9. doi:10.1016/S0002-9378(16)36323-2. PMID 13777540.

- Wikipedia Rostam

- Boss J (1961). "The Antiquity of Caesarean Section with Maternal Survival: The Jewish Tradition". Medical History. 5 (2): 117–31. doi:10.1017/S0025727300026089. PMC 1034600. PMID 16562221.

- "The Truth About Julius Caesar and "Caesarean" Sections". Today I Found Out. 25 October 2013. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- "St. Raymond Nonnatus". Catholic Online. Archived from the original on 19 July 2006. Retrieved 26 July 2006.

- Pařízek, A.; Drška, V.; Říhová, M. (Summer 2016). "Prague 1337, the first successful caesarean section in which both mother and child survived may have occurred in the court of John of Luxembourg, King of Bohemia". Ceska Gynekologie. 81 (4): 321–330. ISSN 1210-7832. PMID 27882755.

- Goeij, Hana de (23 November 2016). "A Breakthrough in C-Section History: Beatrice of Bourbon's Survival in 1337". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- Appropriations, United States Congress House Committee on (1970). Hearings, Reports and Prints of the House Committee on Appropriations. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Henry, John (1991). "Doctors and Healers: Popular Culture and the Medical Profession". In Stephen Pumphrey; Paolo L. Rossi; Maurice Slawinski (eds.). Science, Culture, and Popular Belief in Renaissance Europe. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 197. ISBN 0-7190-2925-2.

- Sewell, Jane Eliot (1993), Cesarean Section: A Brief History (PDF), National Library on Medicine], archived from the original (PDF) on 5 November 2004