Pottery of ancient Greece

Ancient Greek pottery, due to its relative durability, comprises a large part of the archaeological record of ancient Greece, and since there is so much of it (over 100,000 painted vases are recorded in the Corpus vasorum antiquorum),[1] it has exerted a disproportionately large influence on our understanding of Greek society. The shards of pots discarded or buried in the 1st millennium BC are still the best guide available to understand the customary life and mind of the ancient Greeks. There were several vessels produced locally for everyday and kitchen use, yet finer pottery from regions such as Attica was imported by other civilizations throughout the Mediterranean, such as the Etruscans in Italy.[2] There were a multitude of specific regional varieties, such as the South Italian ancient Greek pottery.

Throughout these places, various types and shapes of vases were used. Not all were purely utilitarian; large Geometric amphorae were used as grave markers, kraters in Apulia served as tomb offerings and Panathenaic Amphorae seem to have been looked on partly as objets d’art, as were later terracotta figurines. Some were highly decorative and meant for elite consumption and domestic beautification as much as serving a storage or other function, such as the krater with its usual use in diluting wine.

Earlier Greek styles of pottery, called "Aegean" rather than "Ancient Greek", include Minoan pottery, very sophisticated by its final stages, Cycladic pottery, Minyan ware and then Mycenaean pottery in the Bronze Age, followed by the cultural disruption of the Greek Dark Age. As the culture recovered Sub-Mycenaean pottery finally blended into the Protogeometric style, which begins Ancient Greek pottery proper.

The rise of vase painting saw increasing decoration. Geometric art in Greek pottery was contiguous with the late Dark Age and early Archaic Greece, which saw the rise of the Orientalizing period. The pottery produced in Archaic and Classical Greece included at first black-figure pottery, yet other styles emerged such as red-figure pottery and the white ground technique. Styles such as West Slope Ware were characteristic of the subsequent Hellenistic period, which saw vase painting's decline.

Rediscovery and scholarship

The interest in Greek art lagged behind the revival of classical scholarship during the Renaissance and revived in the academic circle round Nicolas Poussin in Rome in the 1630s. Though modest collections of vases recovered from ancient tombs in Italy were made in the 15th and 16th centuries these were regarded as Etruscan. It is possible that Lorenzo de Medici bought several Attic vases directly from Greece;[3] however the connection between them and the examples excavated in central Italy was not made until much later. Winckelmann's Geschichte der Kunst des Alterthums of 1764 first refuted the Etruscan origin of what we now know to be Greek pottery[4] yet Sir William Hamilton's two collections, one lost at sea the other now in the British Museum, were still published as "Etruscan vases"; it would take until 1837 with Stackelberg's Gräber der Hellenen to conclusively end the controversy.[5]

Much of the early study of Greek vases took the form of production of albums of the images they depict, however neither D'Hancarville's nor Tischbein's folios record the shapes or attempt to supply a date and are therefore unreliable as an archaeological record. Serious attempts at scholarly study made steady progress over the 19th century starting with the founding of the Instituto di Corrispondenza in Rome in 1828 (later the German Archaeological Institute), followed by Eduard Gerhard's pioneering study Auserlesene Griechische Vasenbilder (1840 to 1858), the establishment of the journal Archaeologische Zeitung in 1843 and the Ecole d'Athens 1846. It was Gerhard who first outlined the chronology we now use, namely: Orientalizing (Geometric, Archaic), Black Figure, Red Figure, Polychromatic (Hellenistic).

Finally it was Otto Jahn's 1854 catalogue Vasensammlung of the Pinakothek, Munich, that set the standard for the scientific description of Greek pottery, recording the shapes and inscriptions with a previously unseen fastidiousness. Jahn's study was the standard textbook on the history and chronology of Greek pottery for many years, yet in common with Gerhard he dated the introduction of the red figure technique to a century later than was in fact the case. This error was corrected when the Archaeological Society of Athens undertook the excavation of the Acropolis in 1885 and discovered the so-called "Persian debris" of red figure pots destroyed by Persian invaders in 480 BC. With a more soundly established chronology it was possible for Adolf Furtwängler and his students in the 1880s and 90s to date the strata of his archaeological digs by the nature of the pottery found within them, a method of seriation Flinders Petrie was later to apply to unpainted Egyptian pottery.

Where the 19th century was a period of Greek discovery and the laying out of first principles, the 20th century has been one of consolidation and intellectual industry. Efforts to record and publish the totality of public collections of vases began with the creation of the Corpus vasorum antiquorum under Edmond Pottier and the Beazley archive of John Beazley.

Beazley and others following him have also studied fragments of Greek pottery in institutional collections, and have attributed many painted pieces to individual artists. Scholars have called these fragments disjecta membra (Latin for "scattered parts") and in a number of instances have been able to identify fragments now in different collections that belong to the same vase.[6]

Uses and types

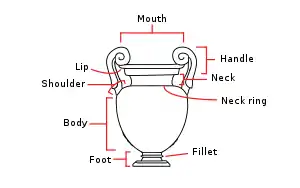

The names we use for Greek vase shapes are often a matter of convention rather than historical fact, a few do illustrate their own use or are labeled with their original names, others are the result of early archaeologists attempt to reconcile the physical object with a known name from Greek literature – not always successfully. To understand the relationship between form and function Greek pottery may be divided in four broad categories, given here with common types:[2][7][8]

- storage and transport vessels, including the amphora, pithos, pelike, hydria, pyxis,

- mixing vessels, mainly for symposia or male drinking parties, including the krater, and dinos,

- jugs and cups, several types of kylix also just called cups, kantharos, phiale, skyphos, oinochoe and loutrophoros,

- vases for oils, perfumes and cosmetics, including the large lekythos, and the small aryballos and alabastron.

As well as these utilitarian functions, certain vase shapes were especially associated with rituals, others with athletics and the gymnasium.[9] Not all of their uses are known, but where there is uncertainty scholars make good proximate guesses of what use a piece would have served. Some have a purely ritual function, for example

Some vessels were designed as grave markers. Craters marked the places of males and amphorae marked those of females.[10] This helped them to survive, and is why some will depict funeral processions.[11] White ground lekythoi contained the oil used as funerary offerings and appear to have been made solely with that object in mind. Many examples have a concealed second cup inside them to give the impression of being full of oil, as such they would have served no other useful gain.

There was an international market for Greek pottery since the 8th century BC, which Athens and Corinth dominated down to the end of the 4th century BC.[12] An idea of the extent of this trade can be gleaned from plotting the find maps of these vases outside of Greece, though this could not account for gifts or immigration. Only the existence of a second hand market could account for the number of panathenaics found in Etruscan tombs. South Italian wares came to dominate the export trade in the Western Mediterranean as Athens declined in political importance during the Hellenistic period.

Clay

The few ways that clay pottery can be damaged is by being broken, being abraded or by coming in contact with fire.[13] The process of making a pot and firing it is fairly simple. The first thing a potter needs is clay. Attica's high-iron clay gave its pots an orange color.[14]

Manufacture

| External video | |

|---|---|

| |

Levigation

When clay is first dug out of the ground it is full of rocks and shells and other useless items that need to be removed. To do this the potter mixes the clay with water and lets all the impurities sink to the bottom. This is called levigation or elutriation. This process can be done many times. The more times this is done, the smoother clay becomes.

Wheel

The clay is then kneaded by the potter and placed on a wheel. Once the clay is on the wheel the potter can shape it into any of the many shapes shown below, or anything else he desires. Wheel-made pottery dates back to roughly 2500 BC where before the coil method of building the walls of the pot was employed. Most Greek vases were wheel-made, though as with the Rhyton mould-made pieces (so-called "plastic" pieces) are also found and decorative elements either hand-formed or by mould were added to thrown pots. More complex pieces were made in parts then assembled when it was leather hard by means of joining with a slip, where the potter returned to the wheel for the final shaping or turning. Sometimes, a young man helped turn the wheel.[16][17]

Clay slip

After the pot is made then the potter paints it with an ultra fine grained clay slip; the paint was applied on the areas intended to become black after firing, according to the two different styles, i.e. the black figure and the red figure.[18] For the decoration the vase painters were using brushes of different thickness, pinpoint tools for incisions and probably single-hair tools for the relief lines[19]

A series of analytical studies have shown that the striking black gloss with a metallic sheen, so characteristic of Greek pottery, emerged from the colloidal fraction of an illitic clay with very low calcium oxide content. This clay slip was rich in iron oxides and hydroxides, differentiating from that used for the body of the vase in terms of the calcium content, the exact mineral composition and the particle size. The fine clay suspension used for the paint was either produced by using several deflocculating additives to clay (potash, urea, dregs of wine, bone ashes, seaweed ashes etc.) or by collecting it in situ from illitic clay beds following rain periods. Recent studies have shown that some trace elements in the black glaze (i.e. Zn in particular) can be characteristic of the clay beds used in antiquity. In general, different teams of scholars suggest different approaches concerning the production of the clay slip used in antiquity.[20][21][22]

Firing

Greek pottery, unlike today's pottery, was only fired once, using a very sophisticated process.[23] The black color effect was achieved by means of changing the amount of oxygen present during firing. This was done in a process known as three-phase firing involving alternating oxidizing -reducing conditions. First, the kiln was heated to around 920–950 °C, with all vents open bringing oxygen into the firing chamber and turning both pot and slip a reddish-brown (oxidising conditions) due to the formation of hematite (Fe2O3) in both the paint and the clay body. Then the vent was closed and green wood introduced, creating carbon monoxide which turns the red hematite to black magnetite (Fe3O4); at this stage the temperature decreases due to incomplete combustion. In a final reoxidizing phase (at about 800–850 °C) the kiln was opened and oxygen reintroduced causing the unslipped reserved clay to go back to orange-red while the slipped area on the vase that had been sintered/vitrified in the previous phase, could no longer be oxidized and remained black.

While the description of a single firing with three stages may seem economical and efficient, some scholars claim that it is equally possible that each of these stages was confined to separate firings [24] in which the pottery is subjected to multiple firings, of different atmosphere. In any case, the faithful reproduction of the process involving extensive experimental work that led to the creation of a modern production unit in Athens since 2000,[25] has shown that the ancient vases may have been subjected to multiple three-stage firings following repainting or as an attempt to correct color failures[20] The technique which is mostly known as the "iron reduction technique" was decoded with the contribution of scholars, ceramists and scientists from the mid 18th century onwards to the end of the 20th century, i.e. Comte de Caylus (1752), Durand-Greville (1891), Binns and Fraser (1925), Schumann (1942), Winter (1959), Bimson (1956), Noble (1960, 1965), Hofmann (1962), Oberlies (1968), Pavicevic (1974), Aloupi (1993). More recent studies by Walton et al. (2009), Walton et al.(2014), Lühl et al.(2014) and Chaviara & Aloupi-Siotis (2016) by using advanced analytical techniques provide detailed information on the process and the raw materials used.[26]

Vase painting

(1) Black-figure amphora by Exekias, Achilles and Ajax engaged in a game, c. 540–530 BC

(2) Red-figure scene of women playing music by the Niobid Painter

(3) Bilingual amphora by the Andokides Painter, c. 520 BC (Munich)

(4) Cylix of Apollo and his raven on a white-ground bowl by the Pistoxenos Painter.

The most familiar aspect of ancient Greek pottery is painted vessels of fine quality. These were not the everyday pottery used by most people but were sufficiently cheap to be accessible to a wide range of the population.

Few examples of ancient Greek painting have survived so modern scholars have to trace the development of ancient Greek art partly through ancient Greek vase-painting, which survives in large quantities and is also, with Ancient Greek literature, the best guide we have to the customary life and mind of the ancient Greeks.

Development of pottery painting

Stone Age

Greek pottery goes back to the Stone Age, such as those found in Sesklo and Dimini.

Bronze Age

More elaborate painting on Greek pottery goes back to the Minoan pottery and Mycenaean pottery of the Bronze Age, some later examples of which show the ambitious figurative painting that was to become highly developed and typical.

Iron Age

After many centuries dominated by styles of geometric decoration, becoming increasingly complex, figurative elements returned in force in the 8th century. From the late 7th century to about 300 BC evolving styles of figure-led painting were at their peak of production and quality and were widely exported.

During the Greek Dark Age, spanning the 11th to 8th centuries BC, the prevalent early style was that of the protogeometric art, predominantly utilizing circular and wavy decorative patterns. This was succeeded in mainland Greece, the Aegean, Anatolia, and Italy by the style of pottery known as geometric art, which employed neat rows of geometric shapes.[27]

The period of Archaic Greece, beginning in the 8th century BC and lasting until the late 5th century BC, saw the birth of Orientalizing period, led largely by ancient Corinth, where the previous stick-figures of the geometric pottery become fleshed out amid motifs that replaced the geometric patterns.[12]

The classical ceramic decor is dominated mostly by Attic vase painting. Attic production was the first to resume after the Greek Dark Age and influenced the rest of Greece, especially Boeotia, Corinth, the Cyclades (in particular Naxos) and the Ionian colonies in the east Aegean.[28] Production of vases was largely the prerogative of Athens – it is well attested that in Corinth, Boeotia, Argos, Crete and Cyclades, the painters and potters were satisfied to follow the Attic style. By the end of the Archaic period the styles of black-figure pottery, red-figure pottery and the white ground technique had become fully established and would continue in use during the era of Classical Greece, from the early 5th to late 4th centuries BC. Corinth was eclipsed by Athenian trends since Athens was the progenitor of both the red-figure and white ground styles.[12]

Protogeometric styles

Vases of the protogeometrical period (c. 1050–900 BC) represent the return of craft production after the collapse of the Mycenaean Palace culture and the ensuing Greek dark ages. It is one of the few modes of artistic expression besides jewelry in this period since the sculpture, monumental architecture and mural painting of this era are unknown to us. By 1050 BC life in the Greek peninsula seems to have become sufficiently settled to allow a marked improvement in the production of earthenware. The style is confined to the rendering of circles, triangles, wavy lines and arcs, but placed with evident consideration and notable dexterity, probably aided by compass' and multiple brushes.[29] The site of Lefkandi is one of our most important sources of ceramics from this period where a cache of grave goods has been found giving evidence of a distinctive Euboian protogeometric style which lasted into the early 8th century.[30]

Geometric style

Geometric art flourished in the 9th and 8th centuries BC. It was characterized by new motifs, breaking with the representation of the Minoan and Mycenaean periods: meanders, triangles and other geometrical decoration (hence the name of the style) as distinct from the predominantly circular figures of the previous style. However, our chronology for this new art form comes from exported wares found in datable contexts overseas.

With the early geometrical style (approximately 900–850 BC) one finds only abstract motifs, in what is called the "Black Dipylon" style, which is characterized by extensive use of black varnish, with the Middle Geometrical (approx. 850–770 BC), figurative decoration makes its appearance: they are initially identical bands of animals such as horses, stags, goats, geese, etc. which alternate with the geometrical bands. In parallel, the decoration becomes complicated and becomes increasingly ornate; the painter feels reluctant to leave empty spaces and fills them with meanders or swastikas. This phase is named horror vacui (fear of the empty) and will not cease until the end of geometrical period.

In the middle of the century there begin to appear human figures, the best known representations of which are those of the vases found in Dipylon, one of the cemeteries of Athens. The fragments of these large funerary vases show mainly processions of chariots or warriors or of the funerary scenes: πρόθεσις / prothesis (exposure and lamentation of dead) or ἐκφορά / ekphora (transport of the coffin to the cemetery). The bodies are represented in a geometrical way except for the calves, which are rather protuberant. In the case of soldiers, a shield in form of a diabolo, called “dipylon shield” because of its characteristic drawing, covers the central part of the body. The legs and the necks of the horses, the wheels of the chariots are represented one beside the other without perspective. The hand of this painter, so called in the absence of signature, is the Dipylon Master, could be identified on several pieces, in particular monumental amphorae.[32]

At the end of the period there appear representations of mythology, probably at the moment when Homer codifies the traditions of Trojan cycle in the Iliad and the Odyssey. Here however the interpretation constitutes a risk for the modern observer: a confrontation between two warriors can be a Homeric duel or simple combat; a failed boat can represent the shipwreck of Odysseus or any hapless sailor.

Lastly, are the local schools that appear in Greece. Production of vases was largely the prerogative of Athens – it is well attested that as in the proto-geometrical period, in Corinth, Boeotia, Argos, Crete and Cyclades, the painters and potters were satisfied to follow the Attic style. From about the 8th century BC on, they created their own styles, Argos specializing in the figurative scenes, Crete remaining attached to a more strict abstraction.[33]

Orientalizing style

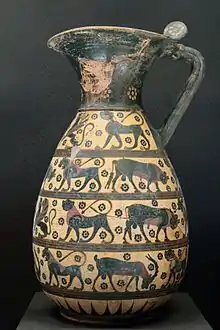

The orientalizing style was the product of cultural ferment in the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean of the 8th and 7th centuries BC. Fostered by trade links with the city-states of Asia Minor, the artifacts of the East influenced a highly stylized yet recognizable representational art. Ivories, pottery and metalwork from the Neo-Hittite principalities of northern Syria and Phoenicia found their way to Greece, as did goods from Anatolian Urartu and Phrygia, yet there was little contact with the cultural centers of Egypt or Assyria. The new idiom developed initially in Corinth (as Proto-Corinthian) and later in Athens between 725 BC and 625 BC (as Proto-Attic).[34]

It was characterized by an expanded vocabulary of motifs: sphinx, griffin, lions, etc., as well as a repertory of non-mythological animals arranged in friezes across the belly of the vase. In these friezes, painters also began to apply lotuses or palmettes. Depictions of humans were relatively rare. Those that have been found are figures in silhouette with some incised detail, perhaps the origin of the incised silhouette figures of the black-figure period. There is sufficient detail on these figures to allow scholars to discern a number of different artists' hands. Geometrical features remained in the style called proto-Corinthian that embraced these Orientalizing experiments, yet which coexisted with a conservative sub-geometric style.

The ceramics of Corinth were exported all over Greece, and their technique arrived in Athens, prompting the development of a less markedly Eastern idiom there. During this time described as Proto-Attic, the orientalizing motifs appear but the features remain not very realistic. The painters show a preference for the typical scenes of the Geometrical Period, like processions of chariots. However, they adopt the principle of line drawing to replace the silhouette. In the middle of the 7th century BC, there appears the black and white style: black figures on a white zone, accompanied by polychromy to render the color of the flesh or clothing. Clay used in Athens was much more orange than that of Corinth, and so did not lend itself as easily to the representation of flesh. Attic Orientalising Painters include the Analatos Painter, the Mesogeia Painter and the Polyphemos Painter.

Crete, and especially the islands of the Cyclades, are characterized by their attraction to the vases known as “plastic”, i.e. those whose paunch or collar is moulded in the shape of head of an animal or a man. At Aegina, the most popular form of the plastic vase is the head of the griffin. The Melanesian amphoras, manufactured at Paros, exhibit little knowledge of Corinthian developments. They present a marked taste for the epic composition and a horror vacui, which is expressed in an abundance of swastikas and meanders.

Finally one can identify the last major style of the period, that of Wild Goat Style, allotted traditionally to Rhodes because of an important discovery within the necropolis of Kameiros. In fact, it is widespread over all of Asia Minor, with centers of production at Miletus and Chios. Two forms prevail oenochoes, which copied bronze models, and dishes, with or without feet. The decoration is organized in superimposed registers in which stylized animals, in particular of feral goats (from whence the name) pursue each other in friezes. Many decorative motifs (floral triangles, swastikas, etc.) fill the empty spaces.

Black-figure technique

Black-figure is the most commonly imagined when one thinks about Greek pottery. It was a popular style in ancient Greece for many years. The black-figure period coincides approximately with the era designated by Winckelmann as the middle to late Archaic, from c. 620 to 480 BC. The technique of incising silhouetted figures with enlivening detail which we now call the black-figure method was a Corinthian invention of the 7th century[35] and spread from there to other city states and regions including Sparta,[36] Boeotia,[37] Euboea,[38] the east Greek islands[39] and Athens.

The Corinthian fabric, extensively studied by Humfry Payne[40] and Darrell Amyx,[41] can be traced though the parallel treatment of animal and human figures. The animal motifs have greater prominence on the vase and show the greatest experimentation in the early phase of Corinthian black-figure. As Corinthian artists gained confidence in their rendering of the human figure the animal frieze declined in size relative to the human scene during the middle to late phase. By the mid-6th century BC, the quality of Corinthian ware had fallen away significantly to the extent that some Corinthian potters would disguise their pots with a red slip in imitation of superior Athenian ware.

At Athens researchers have found the earliest known examples of vase painters signing their work, the first being a dinos by Sophilos (illus. below, BM c. 580), this perhaps indicative of their increasing ambition as artists in producing the monumental work demanded as grave markers, as for example with Kleitias's François Vase. Many scholars consider the finest work in the style to belong Exekias and the Amasis Painter, who are noted for their feeling for composition and narrative.

Circa 520 BC the red-figure technique was developed and was gradually introduced in the form of the bilingual vase by the Andokides Painter, Oltos and Psiax.[42] Red-figure quickly eclipsed black-figure, yet in the unique form of the Panathanaic Amphora, black-figure continued to be utilised well into the 4th century BC.

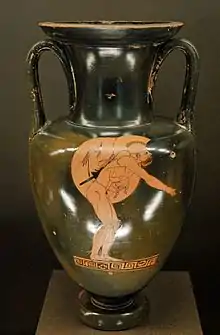

Red-figure technique

The innovation of the red-figure technique was an Athenian invention of the late 6th century. It was quite the opposite of black-figure which had a red background. The ability to render detail by direct painting rather than incision offered new expressive possibilities to artists such as three-quarter profiles, greater anatomical detail and the representation of perspective.

The first generation of red-figure painters worked in both red- and black-figure as well as other methods including Six's technique and white-ground; the latter was developed at the same time as red-figure. However, within twenty years, experimentation had given way to specialization as seen in the vases of the Pioneer Group, whose figural work was exclusively in red-figure, though they retained the use of black-figure for some early floral ornamentation. The shared values and goals of The Pioneers such as Euphronios and Euthymides signal that they were something approaching a self-conscious movement, though they left behind no testament other than their own work. John Boardman said of the research on their work that "the reconstruction of their careers, common purpose, even rivalries, can be taken as an archaeological triumph"[43]

The next generation of late Archaic vase painters (c. 500 to 480 BC) brought an increasing naturalism to the style as seen in the gradual change of the profile eye. This phase also sees the specialization of painters into pot and cup painters, with the Berlin and Kleophrades Painters notable in the former category and Douris and Onesimos in the latter.

By the early to high classical era of red-figure painting (c. 480–425 BC), a number of distinct schools had evolved. The Mannerists associated with the workshop of Myson and exemplified by the Pan Painter hold to the archaic features of stiff drapery and awkward poses and combine that with exaggerated gestures. By contrast, the school of the Berlin Painter in the form of the Achilles Painter and his peers (who may have been the Berlin Painter's pupils) favoured a naturalistic pose usually of a single figure against a solid black background or of restrained white-ground lekythoi. Polygnotos and the Kleophon Painter can be included in the school of the Niobid Painter, as their work indicates something of the influence of the Parthenon sculptures both in theme (e.g., Polygnotos's centauromachy, Brussels, Musées Royaux A. & Hist., A 134) and in feeling for composition.

Toward the end of the century, the "Rich" style of Attic sculpture as seen in the Nike Balustrade is reflected in contemporary vase painting with an ever-greater attention to incidental detail, such as hair and jewellery. The Meidias Painter is usually most closely identified with this style.

Vase production in Athens stopped around 330–320 BC possibly due to Alexander the Great's control of the city, and had been in slow decline over the 4th century along with the political fortunes of Athens itself. However, vase production continued in the 4th and 3rd centuries in the Greek colonies of southern Italy where five regional styles may be distinguished. These are the Apulian, Lucanian, Sicilian, Campanian and Paestan. Red-figure work flourished there with the distinctive addition of polychromatic painting and in the case of the Black Sea colony of Panticapeum the gilded work of the Kerch Style. Several noteworthy artists' work comes down to us including the Darius Painter and the Underworld Painter, both active in the late 4th century, whose crowded polychromatic scenes often essay a complexity of emotion not attempted by earlier painters. Their work represents a late mannerist phase to the achievement of Greek vase painting.

White ground technique

The white-ground technique was developed at the end of the 6th century BC. Unlike the better-known black-figure and red-figure techniques, its coloration was not achieved through the application and firing of slips but through the use of paints and gilding on a surface of white clay. It allowed for a higher level of polychromy than the other techniques, although the vases end up less visually striking. The technique gained great importance during the 5th and 4th centuries, especially in the form of small lekythoi that became typical grave offerings. Important representatives include its inventor, the Achilles Painter, as well as Psiax, the Pistoxenos Painter, and the Thanatos Painter.

Relief and plastic vases

Relief and plastic vases became particularly popular in the 4th century BC and continued being manufactured in the Hellenistic period. They were inspired by the so-called "rich style" developed mainly in Attica after 420 BC. The main features were the multi-figured compositions with use of added colours (pink/reddish, blue, green, gold) and an emphasis on female mythological figures. Theatre and performing constituted yet one more source of inspiration.

Delphi Archaeological Museum has some particularly good examples of this style, including a vase with Aphrodite and Eros. The base is round, cylindrical, and its handle vertical, with bands, covered with black colour. The female figure (Aphrodite) is depicted seated, wearing an himation. Next to her stands a male figure, naked and winged. Both figures wear wreaths made of leaves and their hair preserve traces of golden paint. The features of their faces are stylized. The vase has a white ground and maintains in several parts the traces of bluish, greenish and reddish paint. It dates to the 4th century BC.

In the same room is kept a small lekythos with a plastic decoration, depicting a winged dancer. The figure wears a Persian head cover and an oriental dress, indicating that already in that period oriental dancers, possibly slaves, had become quite fashionable. The figure is also covered with a white colour. The total height of the vase is 18 centimeters and it dates to the 4th century BC.

Hellenistic period

The Hellenistic period, ushered in by the conquests of Alexander the Great, saw the virtual disappearance of black and red-figure pottery yet also the emergence of new styles such as West Slope Ware in the east, the Centuripe Ware in Sicily, and the Gnathia vases to the west.[44] Outside of mainland Greece other regional Greek traditions developed, such as those in Magna Graecia with the various styles in South Italy, including Apulian, Lucanian, Paestan, Campanian, and Sicilian.[12]

Inscriptions

Inscriptions on Greek pottery are of two kinds; the incised (the earliest of which are contemporary with the beginnings of the Greek alphabet in the 8th century BC), and the painted, which only begin to appear a century later. Both forms are relatively common on painted vases until the Hellenistic period when the practice of inscribing pots seems to die out. They are by far most frequently found on Attic pottery.

A number of sub-classes of inscription can be distinguished. Potters and painters occasionally signed their works with epoiesen and egraphsen respectively. Trademarks are found from the start of the 6th century on Corinthian pieces; these may have belonged to an exporting merchant rather than the pottery workfield and this remains a matter of conjecture.) Patrons' names are also sometimes recorded, as are the names of characters and objects depicted. At times we may find a snatch of dialogue to accompany a scene, as in ‘Dysniketos's horse has won’, announces a herald on a Panathenaic amphora (BM, B 144). More puzzling, however, are the kalos and kalee inscriptions, which might have formed part of courtship ritual in Athenian high society, yet are found on a wide variety of vases not necessarily associated with a social setting. Finally there are abecedaria and nonsense inscriptions, though these are largely confined to black-figure pots.[45]

Figurines

Greek terracotta figurines were another important type of pottery, initially mostly religious, but increasingly representing purely decorative subjects. The so-called Tanagra figurines, in fact made elsewhere as well, are one of the most important types. Earlier figurines were usually votive offerings at temples.

Relationship to metalwork and other materials

Several clay vases owed their inspiration to metalwork forms in bronze, silver and sometimes gold. These were increasingly used by the elite when dining, but were not placed in graves, where they would have been robbed, and were often treated as a store of value to be traded as bullion when needed. Very few metal vessels have survived as at some point they were melted down and the metal reused.

In recent decades many scholars have questioned the conventional relationship between the two materials, seeing much more production of painted vases than was formerly thought as made to be placed in graves, as a cheaper substitute for metalware in both Greece and Etruria. The painting itself may also copy that on metal vessels more closely than was thought.[46]

The Derveni Krater, from near Thessaloniki, is a large bronze volute krater from about 320 BC, weighing 40 kilograms, and finely decorated with a 32-centimetre-tall frieze of figures in relief representing Dionysus surrounded by Ariadne and her procession of satyrs and maenads.

The alabastron's name suggests alabaster, stone.[47] Glass was also used, mostly for fancy small perfume bottles, though some Hellenistic glass rivalled metalwork in quality and probably price.

See also

- Conservation and restoration of ancient Greek pottery

- Tanagra figurine

- Kerameikos Archaeological Museum

- Ancient Greek crafts

References and sources

- "The Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum ('Corpus of Ancient Vases') is the oldest research project of the Union Académique Internationale". Corpus vasorum antiquorum. University of Oxford. Union Académique Internationale. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- John H. Oakley (2012). "Greek Art and Architecture, Classical: Classical Greek Pottery," in Neil Asher Silberman et al. (eds), The Oxford Companion to Archaeology, Vol 1: Ache-Hoho, Second Edition, 641–644. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-973578-5, p. 641.

- A letter of 1491 to Lorenzo from Angelo Poliziano made an offer of 3 vases as an addition to an implied existing collection

- Though the first conjecture belongs to A.S Mazochius, In regii herculanensis musaei tabulas hercleenes commentarii, 1754-8, however Winckelmann had access to greater resources including the first plates of the Hamilton collection. See D. von Bothmer, Greek vase-painting in Paper on the Amasis Painter and his World, 1987

- Thanks to the ability of scholars to compare Greek finds with Italian ones following the Greek War of Independence, however the textual analysis in g. Kramer, Uber den Styl und die Herunft der bemalten griechischen Thongefasse 1837 and Otto Jahn's catalogue of the Vulci finds contributed to the changing consensus. See Cook, Greek Painted Pottery, 1997, p.283

- Aaron J. Paul, Fragments of Antiquity: Drawing Upon Greek Vases, Harvard University Art Museums Bulletin, Vol. V, No. 2 (Spring 1997), pp.. 4, 10.

- Woodford, 12–14

- "Shapes". Beazley Archive. Oxford: Classical Art Research Centre. 22 October 2012. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- Woodford, Susan, An Introduction To Greek Art, 1986, Duckworth, ISBN 978-0801419942, p. 12

- "Dipylon vases".

- Scott, Natalie (30 March 2016). "1. Grave Markers of the Ancient Elite". Art 230: Ancient Art Digital Exhibit.

- John H. Oakley (2012). "Greek Art and Architecture, Classical: Classical Greek Pottery," in Neil Asher Silberman et al. (eds), The Oxford Companion to Archaeology, Vol 1: Ache-Hoho, Second Edition, 641–644. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-973578-5, p. 642.

- Von Bothmer, Dietrich (1962). "Painted Greek Vases". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. 21 (1): 2. JSTOR 3258463 – via JSTOR.

- "Greek Pottery". World History Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 2016-10-22.

- "Making Greek Vases". Smarthistory at Khan Academy. Archived from the original on January 3, 2014. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-10-19. Retrieved 2016-10-18.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "ancient Greek pottery". Archived from the original on 2016-10-21.

- For a detailed presentation of the painting process see Penthesilea bowl | Greek vase painting in practice | The red figure technique, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TBB6qArnVDw

- Artal-Isbrand, Paula, and Philip Klausmeyer. "Evaluation of the relief line and the contour line on Greek red-figure vases using reflectance transformation imaging and three-dimensional laser scanning confocal microscopy." Studies in Conservation 58.4 (2013): 338–359.

- Aloupi-Siotis, Ε., 2008. Recovery and Revival of Attic Vase-Decoration Techniques. Special Techniques. In: Lapatin, K. (Ed.), Papers on Special Techniques in Athenian Vases. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, pp. 113–127

- Walton, M.; Trentelman, K.; Cianchetta, I.; Maish, J.; Saunders, D.; Foran, B.; Mehta, A. (2014). "Zn in Athenian Black Gloss Ceramic Slips: A Trace Element Marker for Fabrication Technology". Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 98 (2): 430–436. doi:10.1111/jace.13337.

- Chaviara, A.; Aloupi-Siotis, E. (2016). "The story of a soil that became a glaze: Chemical and microscopic fingerprints on the Attic vases". Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. 7: 510–518. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2015.08.016.

- ATTIC VASES : precious earth. http://www.atticvases.gr/attika-aggeia/1280x720_web.swf

- Walton, M.; Trentelman, K.; Cummings, M.; Poretti, G.; Maish, J.; Saunders, D.; Foran, B.; Brodie, M.; Mehta, A. (2013). "Material Evidence for Multiple Firings of Ancient Athenian Red-Figure Pottery". Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 96 (7): 2031–2035. doi:10.1111/jace.12395.

- The lost art of black glaze ware. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4ILGcewvm0k

- For an extended review on the studies of Attic black slip and research published by several authors see R.E. Jones 1985, Tite M.S., M. Bimson and I. Freestone, "An examination of the high Gloss Surface Finishes on Greek Attic and roman Samian Ware", Archaeometry 24.2(1982):117-26, Maniatis, Y., Aloupi E., Stalios A.D., 1993. "New Evidence for the Nature of the Attic Black Gloss". Archaeometry 35(1), 23-34, Aloupi-Siotis E., "Recovery and Revival of Attic Vase-Decoration Techniques: What can they offer Archaeological Research?", in "Papers on Special Techniques in Athenian Vases" 2008: 113–128, Walton, M., Trentelman, K., Cummings, M., Poretti, G., Maish, J., Saunders, D., Foran, B., Brodie, M., Mehta, A. (2013), "Material Evidence for Multiple Firings of Ancient Athenian Red-Figure Pottery". Journal of the American Ceramic Society, 96: 2031–2035., and Walton, M. S., Doehne, E., Trentelman, K., Chiari, G., Maish, J. and Buxbaum, A. (2009), "Characterization of coral red slips on Green Attic pottery". Archaeometry, 51: 383–396, Lühl L, Hesse B, Mantouvalou I, Wilke M, Mahlkow S, Aloupi-Siotis E, Kanngiesser B., 2014. "Confocal XANES and the Attic black glaze: the three-stage firing process through modern reproduction". Anal Chem. Jul 15;86(14), 6924-30, Chaviara, A. & Aloupi-Siotis, E., 2016. "The story of a soil that became a glaze: Chemical and microscopic fingerprints on the Attic vases". Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 7, 510-518.

- John H. Oakley (2012). "Greek Art and Architecture, Classical: Classical Greek Pottery," in Neil Asher Silberman et al. (eds), The Oxford Companion to Archaeology, Vol 1: Ache-Hoho, Second Edition, 641–644. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-973578-5, p. 641-642.

- The diffusion of protogeometric pottery is a complex subject best summarized by V. Desborough, Protogeometric Pottery, 1952. The picture is further complicated with the presence of a lingering sub-Mycenaean style in some Greek centres during this period, see Desborough (1964). The Last Mycenaeans and their Successors: An Archaeological Survey, c. 1200 – c. 1000 B.C.

- Papadopoulos, John K.; Vedder, James F.; Schreiber, Toby (1998). "Drawing Circles: Experimental Archaeology and the Pivoted Multiple Brush". American Journal of Archaeology. 102 (3): 507–529. doi:10.2307/506399. JSTOR 506399.

- Snodgrass, Anthony M. (2001). The Dark Age of Greece. New York: Routledge. p. 102. ISBN 0-415-93635-7. See also Popham, Sackett, Excavations at Lefkandi, Euboea 1968

- Woodford, Susan. (1982) The Art of Greece and Rome. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 40. ISBN 0521298733

- The relationship between the iconography of grave markers and social change is essayed in James Whitley Style and Society in Dark Age Greece, 1991. See also Gudrun Ahlberg, Gudrun Ahlberg-Cornell, Prothesis and Ekphora in Greek Geometric Art, 1971.

- Diffusion of the style is detailed in John Nicolas Coldstream, Greek Geometric Pottery: A Survey of Ten Local Styles and Their Chronology, 1968

- Robert Manuel Cook, Greek Painted Pottery, Routledge, 1997, p. 43.

- The terminus ante quem of the late Corinthian black-figure style was established by M. T. Campbell A Well of the Black-figured Period at Corinth, Hesperia, vii (1938), pp. 557–611.

- C. M. Stibbe Lakonische Vasenmaler des sechsten Jahrhunderts v.chr., 2 vols, 1972. M. Pipili Laconian Iconography of the Sixth Century BC, 1987

- K. Kilinski II Boiotian Black Figure Vase Painting of the Archaic Period, 1990

- J. Boardman Pottery from Eretria, Annu. Brit. Sch. Athens, xlvii, 1952, pp. 1–48

- R. M. Cook and P. Dupont East Greek Pottery, 1998

- H. G. G. Payne Necrocorinthia: A Study of Corinthian Art in the Archaic Period, 1931.

- D. A. Amyx, Corinthian Vase-painting of the Archaic Period, 3 vols, 1991

- However, the earliest red-figure vase was not a bilingual, see Beth Cohen, The Colors of Clay, p.21

- J. Boardman: Athenian Red Figure Vases: The Archaic Period, 1975, p29.

- John H. Oakley (2012). "Greek Art and Architecture, Classical: Classical Greek Pottery," in Neil Asher Silberman et al. (eds), The Oxford Companion to Archaeology, Vol 1: Ache-Hoho, Second Edition, 641–644. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-973578-5, p. 642-643.

- Henry R. Immerwahr, Aspects of Literacy in the Athenian Ceramicus

- Preface to Ancient Greek Pottery (Ashmolean Handbooks) by Michael Vickers (1991)

- Sparkes, p. 70

- Sparkes, Brian (1991). Greek Pottery: An Introduction. ISBN 978-0-7190-2936-3.

| Library resources about Pottery of ancient Greece |

Further reading

- Aulsebrook, S. (2018) Rethinking Standardization: the Social Meanings of Mycenaean Metal Cups. Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 25 January 2018, doi: 10.1111/ojoa.12134.

- Beazley, John. Attic Red-Figure Vase Painters. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1942.

- --. The Development of Attic Black-Figure. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1951.

- --. Attic Black-Figure Vase Painters. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1956.

- --. Paralipomena. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971.

- Boardman, John. Athenian Black Figure Vases. New York: Oxford University Press, 1974.

- --. Athenian Red Figure Vases: The Archaic Period: A Handbook. London: Thames and Hudson, 1975.

- --. Athenian Red Figure Vases: The Classical Period: A Handbook. London: Thames and Hudson, 1989.

- --. Early Greek Vase Painting: 11th-6th Centuries BC: A Handbook. London: Thames and Hudson, 1998.

- Bundrick, Sheramy D. Music and Image In Classical Athens. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Cohen, Beth. The Colors of Clay: Special Techniques In Athenian Vases. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2006.

- Coldstream, J. N. Geometric Greece: 900-700 BC. 2nd ed. London: Routledge, 2003.

- Herford, Mary Antonie Beatrice. A Handbook of Greek Vase Painting. Sparks, NV: Falcon Hill Press, 1995.

- Mitchell, Alexandre G. Greek Vase-Painting and the Origins of Visual Humour. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Noble, Joseph Veach. The Techniques of Painted Attic Pottery. New York: Watson-Guptill, 1965.

- Oakley, John Howard. The Greek Vase: Art of the Storyteller. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2013.

- Pollitt, J. J. The Cambridge History of Painting In the Classical World. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- Robertson, Martin. The Art of Vase-Painting In Classical Athens. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

- Steiner, Ann. Reading Greek Vases. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Trendall, A. D. Red Figure Vases of South Italy and Sicily: A Handbook. London: Thames & Hudson, 1989.

- Vickers, Michael J. Ancient Greek Pottery. Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, 1999.

- Von Bothmer, Dietrich. Greek Vase Painting. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1987.

- Winter, Adam. Die Antike Glanztonkeramik: Praktische Versuche. Mainz am Rhein: P. von Zabern, 1978.

- Yatromanolakis, Dimitrios. An Archaeology of Representations: Ancient Greek Vase-Painting and Contemporary Methodologies. Athens: Institut du Livre, A. Kardamitsa, 2009.

- --. Epigraphy of Art: Ancient Greek Vase-Inscriptions and Vase-Paintings. Oxford: Archaeopress, 2016.

External links

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art Guide, a collection catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art containing information on the pottery of ancient Greece (pages 315–322)

- Beazley Archive of Greek pottery

- Journey through art history: Ancient Greek Art

- Ancient Greek Pottery, professor Kenney Mencher, Ohlone College

- S. Bleecker-Luce, A Brief History of the Study of Greek Vase Painting, American Philosophical Society 1918

- The evolution of Greek vase painting. Ure Museum of Greek Archaeology.

.jpg.webp)