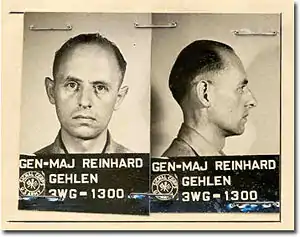

Reinhard Gehlen

Reinhard Gehlen (3 April 1902 – 8 June 1979) was a German lieutenant-general and intelligence officer. He was chief of the Wehrmacht Foreign Armies East military intelligence service on the eastern front during World War II, spymaster of the CIA-affiliated anticommunist Gehlen Organisation (1946–56) and the founding president of the Federal Intelligence Service (Bundesnachrichtendienst, BND) of West Germany (1956–68) during the Cold War.

Reinhard Gehlen | |

|---|---|

Colonel Reinhard Gehlen, c. 1943 | |

| Born | 3 March 1902 Erfurt,Province of Saxony,Kingdom of Prussia, German Empire |

| Died | 8 June 1979 (aged 77) Starnberg, West Germany |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | Army |

| Rank | Generalleutnant |

| Battles/wars | World War II Cold War |

| Awards | Deutsches Kreuz in silver War Merit Cross Großes Bundesverdienstkreuz am Schulterband Grand Cross of the Order pro Merito Melitensi of the Order of Malta (1948) |

Gehlen became a professional soldier in 1920 during the Weimar Republic. In 1942, he became chief of Foreign Armies East (FHO), the German Army's military intelligence unit on the Eastern Front (1941–45). He achieved the rank of major general before he was fired by Adolf Hitler in April 1945 because of the FHO's "defeatism",[1] the pessimistic intelligence reports about Red Army superiority.[2]

In late 1945, following the 7 May surrender of Germany and the start of the Cold War, the U.S. military (G-2 Intelligence) recruited him to establish the Gehlen Organisation, an espionage network focusing on the Soviet Union. The organisation would employ former military officers of the Wehrmacht as well as former intelligence officers of the Schutzstaffel (SS) and the Sicherheitsdienst (SD).[3] As head of the Gehlen Organization he sought cooperation with the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), formed in 1947, resulting in the Gehlen Organization ultimately becoming closely affiliated with the CIA.

Gehlen was instrumental in negotiations to establish an official West German intelligence service based on the Gehlen Organisation of the early 1950s. In 1956, the Gehlen Organisation was transferred to the West German government and formed the core of the Federal Intelligence Service, the Federal Republic of Germany's official foreign intelligence service, with Gehlen serving as its first president until his retirement in 1968.[4][5] While this was a civilian office, he was also a lieutenant-general in the Reserve forces of the Bundeswehr, the highest-ranking reserve-officer in the military of West Germany.[6] He received the Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany in 1968.

Early life

Gehlen was born 1902 into a Catholic family in Erfurt. He had two brothers and a sister. He grew up in Breslau where his father, a former army officer became book publisher for the Ferdinand-Hirt-Verlag, a pubishing house specializing in school books.[7]

In 1920, Gehlen made Abitur and joined the Reichswehr.[8]

Career

After graduating from the German Staff College in 1935, Gehlen was promoted to captain and assigned to the German General Staff.[9]

Gehlen served on the General Staff until 1936 and was promoted to major in 1939; at the time of the German attack on Poland (1 September 1939), he was a staff officer in an infantry division.[9] In 1940, he became liaison officer to Field Marshal Walther von Brauchitsch, Army Commander-in-Chief; and later was transferred to the staff of General Franz Halder, the Chief of the German General Staff. In July 1941, he received a promotion to lieutenant-colonel and was sent to the Eastern Front, where he was assigned as senior intelligence-officer to the Fremde Heere Ost (FHO) section of the Staff.

Head of FHO

In spring of 1942, Gehlen assumed command of the Fremde Heere Ost (FHO) from Colonel Eberhard Kinzel.[10] Before the Wehrmacht disasters in the Battle of Stalingrad (23 August 1942 – 2 February 1943), a year into the German war against the Soviet Union, Gehlen understood that the FHO required fundamental re-organisation, and secured a staff of army linguists and geographers, anthropologists, lawyers, and junior military officers who would improve the FHO as a military-intelligence organisation despite the Nazi ideology of Slavic inferiority.[11]

Hitler assassination plot, 1944

In summer 1944, Colonel Henning von Tresckow, Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg, and General Adolf Heusinger asked Gehlen to participate in their plot to assassinate Adolf Hitler.[12] As head of the FHO, Gehlen allowed the military conspirators to make their plans under his protection, and he was present at their meetings at Berchtesgaden. However, after the bomb plot failed on 20 July, he escaped falling victim to Hitler's revenge.[13]

Dismissal, 1945

Gehlen's cadre of FHO intelligence-officers produced accurate field-intelligence about the Red Army that frequently contradicted rear-echelon perceptions of the eastern battle front. Hitler dismissed the gathered information as defeatism and philosophically harmful to the Nazi cause against "Judeo-Bolshevism" in Russia. In April 1945, despite the accuracy of the intelligence, Hitler dismissed Gehlen, soon after his promotion to major general.[14]

Preparation for Post-War

The FHO collection of both military and political intelligence from captured Red Army soldiers assured Gehlen's post–WWII survival as a Western anticommunist spymaster, with networks of spies and secret agents in the countries of Soviet-occupied Europe. During the German war against the Soviet Union in 1941 to 1945, Gehlen's FHO collected much tactical military intelligence about the Red Army, and much strategic political intelligence about the Soviet Union. Understanding that the Soviet Union would defeat and occupy the Third Reich, Gehlen ordered the FHO intelligence files copied to microfilm; the FHO files proper were stored in watertight drums and buried in various locations in the Austrian Alps.[15]

They amounted to fifty cases of German intelligence about the Soviet Union, which were at Gehlen's disposal for sale to western intelligence services.[16] Meanwhile, as of 1946, when the Soviets consolidated their hegemony and sphere of influence in Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe as agreed at the Potsdam Conference of 1945 and demarcated with what became known as the Iron Curtain, the Western Allies of World War II, the U.S, Britain, France, had no sources of covert information within the countries in which the occupying Red Army had vanquished the Wehrmacht.

After Second World War

On 22 May 1945, Gehlen surrendered to the Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC) of the U.S. Army in Bavaria and was taken to Camp King, near Oberursel, and interrogated by Captain John R. Boker. The American Army recognised his potential value as a spymaster with great knowledge of Soviet forces and anticommunist intelligence contacts in the Soviet Union. In exchange for his liberty and the liberty of his command (prisoners of the US Army), Gehlen offered the Counter Intelligence Corps access to the FHO's intelligence archives and to his anticommunist espionage network in the Soviet Union, known later as the Gehlen Organization.[9] Boker removed his name and those of his Wehrmacht command from the official lists of German prisoners of war, and transferred seven FHO senior officers to join Gehlen.

The FHO archives were unearthed and secretly taken to Camp King, ostensibly without the knowledge of the camp commander. By the end of summer 1945, Boker had the support of Brigadier General Edwin Sibert, the G2 (senior intelligence officer) of the U.S. Twelfth Army Group,[17] who arranged the secret transport of Gehlen, his officers and the FHO intelligence archives, authorized by his superiors in the chain of command, General Walter Bedell Smith (chief of staff for General Eisenhower), who worked with William Donovan (former OSS chief) and Allen Dulles (OSS chief), who also was the OSS station-chief in Bern. On 20 September 1945, Gehlen and three associates were flown from the American Zone of Occupation in Germany to the US, to become spies for the US government.[18]

In July 1946, the US officially released Gehlen and returned him to occupied Germany.[19] On 6 December 1946, he began espionage operations against the Soviet Union, by establishing what was known to US intelligence as the Gehlen Organisation or "the Org", a secret intelligence service composed of former intelligence officers of the Wehrmacht and members of the SS and the SD, which was headquartered first at Oberursel, near Frankfurt, then at Pullach, near Munich.[9] The organisation's cover-name was the South German Industrial Development Organization. Gehlen initially selected 350 ex-intelligence officers of the Wehrmacht as staff; eventually, the organisation comprised some 4,000 anticommunist secret agents.[20][21]

Gehlen Organisation, 1947-56

After he started working for the U.S. Government, Gehlen was subordinate to US Army G-2 (Intelligence). He resented this arrangement and in 1947, the year after his Organisation was established, Gehlen arranged for a transfer and became subordinate to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). The agency kept close control of the Gehlen Organisation, because for many years during the Cold War of 1945–91, its agents were the CIA's only assets in the countries of the Eastern Bloc.

Between 1947 and 1955, agents of the Gehlen Organisation interviewed every German PoW who returned to West Germany from captivity in the Soviet Union. The network employed hundreds of former Wehrmacht and SS officers, and also had close contacts with the anti-Communist organisations of the East European émigré communities in Western Europe. They observed the operations of the railroad systems, airfields, and ports of the USSR, and their secret agents infiltrated the Baltic Soviet Republics and the Ukrainian SSR. Among their successes was Operation Bohemia, a major effort of anti-communist counter-espionage.[22]

The security and efficacy of the Gehlen Organisation were compromised by East German moles within it, such as Johannes Clemens, Erwin Tiebel and Heinz Felfe who were feeding information to the Soviets while in the Org and later, while in the BND that was headed by Gehlen.[23] All three were eventually discovered and convicted in 1963.[24]

There were also Communists and their sympathizers within the CIA and the SIS (MI6), especially Kim Philby, himself a Soviet secret agent. As such information appeared, Gehlen, personally, and the Gehlen Organisation, officially, were attacked by the governments of the Western powers.[25] The British government was especially hostile towards Gehlen, and the politically liberal British press ensured full publication of the existence of the Gehlen Organisation, which compromised the operation.[26]

Federal Intelligence Service (BND), 1956-1968

On 1 April 1956, 11 years after World War II had ended, the U.S. Government and the CIA formally transferred the Gehlen Organisation to the authority of what was by then the Federal Republic of Germany, under Chancellor Konrad Adenauer (1949–63).[9] By way of that transfer of geopolitical sponsorship, the anti–Communist Gehlen Organisation became the nucleus of the Bundesnachrichtendienst (BND, Federal Intelligence Service).[9]

Gehlen became president of the BND as an espionage service, until he was forced out of office in 1968. The end of Gehlen's career as a spymaster resulted from a confluence of events in West Germany: the exposure of a KGB mole, Heinz Felfe, (a former SS lieutenant) working at BND headquarters;[27] political estrangement from Adenauer, in 1963, which aggravated his professional problems; and the inefficiency of the BND consequent to Gehlen's poor leadership and continual inattention to the business of counter-espionage as national defence.

Gehlen's refusal to correct reports with questionable content strained the organization's credibility, and dazzling achievements became an infrequent commodity. A veteran agent remarked at the time that the BND pond then contained some sardines, though a few years earlier the pond had been alive with sharks.[28]

The fact that the BND could score certain successes despite East German Stasi interference, internal malpractice, inefficiencies and infighting, was primarily due to select members of the staff who took it upon themselves to step up and overcome then existing maladies. Abdication of responsibility by Reinhard Gehlen was the malignancy; bureaucracy and cronyism remained pervasive, even nepotism (at one time Gehlen had 16 members of his extended family on the BND payroll).[29] Only slowly did the younger generation then advance to substitute new ideas for some of the bad habits caused mainly by Gehlen's semi-retired attitude and frequent holiday absences.[29]

Gehlen was forced out of the BND due to "political scandal within the ranks", according to one source, He retired in 1968 as a civil servant of West Germany, classified as a Ministerialdirektor, a senior grade with a generous pension. His successor, Bundeswehr Brigadier General Gerhard Wessel, immediately called for a program of modernization and streamlining.[30]

Honours

- Iron Cross second class

- War Merit Cross second and first class with swords

- German Cross in silver (1945)

- Grand Cross of the Order pro Merito Melitensi of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta (1948)

- Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany (1968)

- Good Conduct Medal (United States)

Criticism

Several publications have criticized the fact that Gehlen allowed former Nazis to work for the agencies. The authors of the book A Nazi Past: Recasting German Identity in Postwar Europe stated that Reinhard Gehlen simply did not want to know the backgrounds of the men whom the BND hired in the 1950s.[31] The American National Security Archive states that "he employed numerous former Nazis and known war criminals".[32]

An article in The Independent on 29 June 2018 made this statement about BND employees:[33]

"Operating until 1956, when it was superseded by the BND, the Gehlen Organisation was allowed to employ at least 100 former Gestapo or SS officers.... Among them were Adolf Eichmann’s deputy Alois Brunner, who would go on to die of old age despite having sent more than 100,000 Jews to ghettos or internment camps, and ex-SS major Emil Augsburg.... Many ex-Nazi functionaries including Silberbauer, the captor of Anne Frank, transferred over from the Gehlen Organisation to the BND.... Instead of expelling them, the BND even seems to have been willing to recruit more of them – at least for a few years".

On the other hand, Gehlen himself was cleared by the CIA's James H. Critchfield, who worked with the Gehlen Organization from 1949 to 1956. In 2001, he said that "almost everything negative that has been written about Gehlen, [as an] ardent ex-Nazi, one of Hitler's war criminals ... is all far from the fact," as quoted in the Washington Post. Critchfield added that Gehlen hired the former Sicherheitsdienst (Security Service of the Reichsführer-SS) men "reluctantly, under pressure from German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer to deal with 'the avalanche of subversion hitting them from East Germany'".[4]

Legacy

Gehlen's memoirs were published in 1977 by World Publishers, New York. In the same year another book was published about him, The General Was a Spy, by Heinz Hoehne and Herman Zolling, Coward, McCann and Geoghegan, New York, A review of the latter, published by the CIA in 1996, calls it a "poor book" and goes on to allege that "so much of it is sheer garbage" because of many errors. The CIA review also discusses another book, Gehlen, Spy of the Century, by E. H. Cookridge, Hodder and Stoughton, London, 1971, and claims that it is "chock full of errors". The CIA review is kinder when speaking of Gehlen's memoirs but makes this comment:[34]

"Gehlen's descriptions of most of his so-called successes in the political intelligence field are, in my opinion, either wishful thinking or self-delusion.... Gehlen was never a good clandestine operator, nor was he a particularly good administrator. And therein lay his failures. The Gehlen Organization/BND always had a good record in the collection of military and economic intelligence on East Germany and the Soviet forces there. But this information, for the most part, came from observation and not from clandestine penetration".

Upon Gehlen's retirement in 1968, a CIA note on Gehlen describes him as "essentially a military officer in habits and attitudes". He was also characterized as "essentially a conservative", who refrained from entertaining and drinking, was fluent in English, and was at ease among senior American officials.[35]

References

- Critchfield, Lois M. (30 November 2018). James H. Critchfield: His Life's Story (1917–2003). AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-5462-6975-5.

- "Intelligence Officer's Bookshelf" (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency.

- Richelson, J.T. (1997). A Century of Spies: Intelligence in the Twentieth Century. A Century of Spies: Intelligence in the Twentieth Century. Oxford University Press. pp. 233, 235. ISBN 978-0-19-976173-9.

- Lardner, George Jr. (18 March 2001). "CIA Declassifies Its Records On Dealings With Ex-Nazis". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- "Gehlen Organization - German Intelligence Agencies". www.globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- Pahl, Magnus. Fremde Heere Ost: Hitlers militärische Feindaufklärung, p. 32, Ch. Links Verlag, 2013, ISBN 3862842037.

- "Reinhard Gehlen - Munzinger Biographie". www.munzinger.de. Retrieved 12 October 2022.

- Müller, Rolf-Dieter (20 April 2018). Reinhard Gehlen. Geheimdienstchef im Hintergrund der Bonner Republik: Die Biografie (in German). Ch. Links Verlag. ISBN 978-3-86284-409-8.

- "Reinhard Gehlen - Biografie WHO'S WHO". whoswho.de. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- Höhne, Heinz; Zolling, Hermann (1972). The General Was a Spy: The Truth about General Gehlen and His Spy Ring. New York: Coward, McCann & Geoghegan. p. 10. ISBN 0698104307.

- Höhne & Zolling, p. 13.

- Reinhard Gehlen, pp. 97–99.

- Höhne & Zolling, p. 38.

- Höhne & Zolling, p. 44.

- Simpson, Christopher (1988). Blowback: The First Full Account of America's Recruitment of Nazis, and its Disastrous Effect on Our Domestic Foreign Policy. New York: Collier Books. p. 41. ISBN 0-02-044995-X.

- Höhne & Zolling, p. 52.

- Simpson, pp. 41–42.

- "The German Strategic Mastermind Behind America's Post-War Order". Palladium. 13 April 2019. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- Höhne & Zolling, p. 63.

- Gutman, W. E. (22 August 2012). A Paler Shade of Red: Memoirs of a Radical. CCB Publishing. ISBN 978-1-927360-97-2.

- "Foreign News: Spy Service". Time. 11 July 1955. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- Höhne & Zolling, p. 157.

- Richelson, Jeffery T. (17 July 1997). A Century of Spies: Intelligence in the Twentieth Century. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-976173-9.

- Childs, David; Popplewell, Richard (27 July 2016). The Stasi: The East German Intelligence and Security Service. Springer. ISBN 978-1-349-15054-0.

- Bagley, Tennent H. (1 January 2007). Spy Wars: Moles, Mysteries, and Deadly Games. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-13478-0.

- Höhne & Zolling, p. 172.

- BND cryptanalysts deciphered KGB messages that led to Felfe.

- Höhne & Zolling, p. 213

- Höhne & Zolling, p. 245

- Höhne & Zolling, p. 255

- Messenger, David A.; Paehler, Katrin (21 April 2015). A Nazi Past: Recasting German Identity in Postwar Europe. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-6057-3.

- "The CIA and Nazi War Criminals". nsarchive2.gwu.edu. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- "Himmler's daughter worked for Germany's foreign intelligence agency in 1960s, officials admit". The Independent. 29 June 2018. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- "The Service: The Memoirs of General Reinhard Gehlen by Reinhard Gehlen. Book review by Anonymous — Central Intelligence Agency". 2 February 2017. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- "Biographic sketch on General Reinhard Gehlen" (PDF). CIA.gov. 1968. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 January 2017.

Bibliography and sources

- Cookridge, E. H. Gehlen: Spy of the Century. London: Hodder & Stoughton. 1971, and New York: Random House. 1972

- Critchfield, James H.: Partners at Creation: The Men Behind Postwar Germany's Defense and Intelligence Establishments. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2003. x + 243 pp, ISBN 1-59114-136-2.

- Hastings, Max (2015). The Secret War: Spies, Codes and Guerrillas 1939 -1945 (Paperback). London: William Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-750374-2.

- Hersh, Burton. The Old Boys – The American Elite and the Origins of the CIA. New York: Scribner's. 1992

- Höhne, Heinz; Zolling, Hermann (1972). The General Was a Spy: The Truth about General Gehlen and his spy ring. New York: Coward, McCann & Geoghegan. ISBN 0698104307.

- Kross, Peter. "Intelligence" in Military Heritage, October 2004, pp. 26–30

- Reese, Mary Ellen. General Reinhard Gehlen: The CIA Connection. Fairfax, Virginia: George Mason University. 1990

- United States National Archives, Washington, D.C. NARA Collection of Foreign Records Seized, Microfilm T-77, T-78

- Weiner, Tim. Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA, Trade Paperback, pp. 10–190, Anchor Books. 2008. ISBN 978-0-307-38900-8

Literature

External links

- "Disclosure" newsletter, Information promulgated by the U.S. National Archives & Records Administration

- Forging an Intelligence Partnership: CIA and the Origins of the BND, 1945–49 CIA declassified documents on the Gehlen Organization.

- Reinhard Gehlen's CIA file on the Internet Archive.