Benin

Benin (/bɛˈniːn/ (![]() listen) ben-EEN, /bɪˈniːn/ bin-EEN;[9] French: Bénin [benɛ̃]), officially the Republic of Benin (French: République du Bénin), and formerly Dahomey,[10] is a country in West Africa. It is bordered by Togo to the west, Nigeria to the east, Burkina Faso to the north-west, and Niger to the north-east. The majority of its population lives on the southern coastline of the Bight of Benin, part of the Gulf of Guinea in the northernmost tropical portion of the Atlantic Ocean.[11] The capital is Porto-Novo, and the seat of government is in Cotonou, the most populous city and economic capital. Benin covers an area of 114,763 square kilometres (44,310 sq mi)[4] and its population in 2021 was estimated to be approximately 13 million.[12][13] It is a tropical nation, dependent on agriculture, and is an exporter of palm oil and cotton. Some employment and income arise from subsistence farming.[14]

listen) ben-EEN, /bɪˈniːn/ bin-EEN;[9] French: Bénin [benɛ̃]), officially the Republic of Benin (French: République du Bénin), and formerly Dahomey,[10] is a country in West Africa. It is bordered by Togo to the west, Nigeria to the east, Burkina Faso to the north-west, and Niger to the north-east. The majority of its population lives on the southern coastline of the Bight of Benin, part of the Gulf of Guinea in the northernmost tropical portion of the Atlantic Ocean.[11] The capital is Porto-Novo, and the seat of government is in Cotonou, the most populous city and economic capital. Benin covers an area of 114,763 square kilometres (44,310 sq mi)[4] and its population in 2021 was estimated to be approximately 13 million.[12][13] It is a tropical nation, dependent on agriculture, and is an exporter of palm oil and cotton. Some employment and income arise from subsistence farming.[14]

Republic of Benin | |

|---|---|

Flag

Coat of arms

| |

Motto:

| |

Anthem:

| |

.svg.png.webp) Location of Benin (dark green) | |

| Capital | Porto-Novoa |

| Largest city | Cotonou |

| Official languages | French |

| National languages | |

| Ethnic groups (2013 census[1]) | |

| Religion |

|

| Demonym(s) |

|

| Government | Unitary presidential republic |

• President | Patrice Talon |

• Vice President | Mariam Chabi Talata |

| Legislature | National Assembly |

| Independence | |

• Republic of Dahomey established | 11 December 1958 |

• from France | 1 August 1960 |

| Area | |

• Total | 114,763 km2 (44,310 sq mi)[4] (100th) |

• Water (%) | 0.4% |

| Population | |

• 2022 estimate | 13,754,688[5] (74th) |

• Density | 94.8/km2 (245.5/sq mi) |

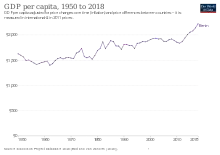

| GDP (PPP) | 2019 estimate |

• Total | $29.918 billion[6] (137th) |

• Per capita | $2,552[6] (163rd) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2019 estimate |

• Total | $11.386 billion[6] (141st) |

• Per capita | $971[6] (163rd) |

| Gini (2015) | high |

| HDI (2019) | low · 158th |

| Currency | West African CFA franc (XOF) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (WAT) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +229 |

| ISO 3166 code | BJ |

| Internet TLD | .bj |

| |

The official language of Benin is French, with indigenous languages such as Fon, Bariba, Yoruba and Dendi also spoken. The largest religious group in Benin is Sunni Islam (27.7%), followed by Roman Catholicism (25.5%), Vodun (11.6%), and Protestantism.[2] Benin is a member of the United Nations, the African Union, the Economic Community of West African States, the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, the South Atlantic Peace and Cooperation Zone, La Francophonie, the Community of Sahel–Saharan States, the African Petroleum Producers Association and the Niger Basin Authority.

From the 17th to the 19th century, political entities in the area included the Kingdom of Dahomey, the city-state of Porto-Novo, and other states to the north. This region was referred to as the Slave Coast from the early 17th century due to the high number of people who were sold and trafficked during the Atlantic slave trade to the New World. France took over the territory in 1894, incorporating it into French West Africa as French Dahomey. In 1960, Dahomey gained full independence from France. As a sovereign state, Benin has had democratic governments, military coups, and military governments. A self-described Marxist–Leninist state called the People's Republic of Benin existed between 1975 and 1990. In 1991, it was replaced by the multi-party Republic of Benin.[15]

History

Pre-colonial

Prior to 1600, present-day Benin comprised a variety of areas with different political systems and ethnicities. These included city-states along the coast (primarily of the Aja ethnic group, and also including Yoruba and Gbe peoples) and tribal regions inland (composed of Bariba, Mahi, Gedevi, and Kabye peoples). The Oyo Empire, located primarily to the east of Benin, was a military force in the region, conducting raids and exacting tribute from the coastal kingdoms and tribal regions.[16] The situation changed in the 17th and 18th centuries as the Kingdom of Dahomey, consisting mostly of Fon people, was founded on the Abomey plateau and began taking over areas along the coast.[17] By 1727, King Agaja of the Kingdom of Dahomey had conquered the coastal cities of Allada and Whydah. Dahomey had become a tributary of the Oyo Empire, and rivaled but did not directly attack the Oyo-allied city-state of Porto-Novo.[18] The rise of Dahomey, its rivalry with Porto-Novo, and tribal politics in the northern region persisted into the colonial and post-colonial periods.[19]

In the Dahomey, some younger people were apprenticed to older soldiers and taught the kingdom's military customs until they were old enough to join the army.[20] Dahomey instituted an elite female soldier corps variously called Ahosi (the king's wives), Mino ("our mothers" in Fongbe), or the "Dahomean Amazons". This emphasis on military preparation and achievement earned Dahomey the nickname of "Black Sparta" from European observers and 19th-century explorers such as Sir Richard Burton.[21]

.jpg.webp)

The kings of Dahomey sold their war captives into transatlantic slavery[22] or killed them ritually in a ceremony known as the Annual Customs. By about 1750, the King of Dahomey was earning an estimated £250,000 per year by selling African captives to European slave-traders.[23] The area was named the "Slave Coast" because of a flourishing slave trade. Court protocols which demanded that a portion of war captives from the kingdom's battles be decapitated, decreased the number of enslaved people exported from the area. The number went from 102,000 people per decade in the 1780s to 24,000 per decade by the 1860s.[24] The decline was partly due to the Slave Trade Act 1807 banning the trans-Atlantic slave trade by Britain in 1808, followed by other countries.[23] This decline continued until 1885 when the last slave ship departed the modern Benin Republic for Brazil, which had yet to abolish slavery. The capital Porto-Novo ("New Port" in Portuguese) was originally developed as a port for the slave trade.

Among the goods the Portuguese sought were carved items of ivory made by Benin's artisans in the form of carved saltcellars, spoons, and hunting horns - pieces of African art produced for sale abroad as exotic objects.[25]

Colonial

By the middle of the 19th century, Dahomey had "begun to weaken and lose its status as the regional power". The French took over the area in 1892. In 1899, the French included the land called French Dahomey within the larger French West Africa colonial region.

France sought to benefit from Dahomey and the region "appeared to lack the necessary agricultural or mineral resources for large-scale capitalist development". As a result, France treated Dahomey as a sort of preserve in case future discoveries revealed resources worth developing.[26]

The French government outlawed the capture and sale of slaves. Previous slaveowners sought to redefine their control over slaves as control over land, tenants, and lineage members. This provoked a struggle among Dahomeans, "concentrated in the period from 1895 to 1920, for the redistribution of control over land and labor. Villages sought to redefine boundaries of lands and fishing preserves. Religious disputes scarcely veiled the factional struggles over control of land and commerce which underlay them. Factions struggled for the leadership of great families".[24]

In 1958, France granted autonomy to the Republic of Dahomey, and full independence on 1 August 1960 which is celebrated each year as Independence Day, a national holiday.[27] The president who led the country to independence was Hubert Maga.[28][29]

Post-colonial

After 1960, there were coups and regime changes, with the figures of Hubert Maga, Sourou Apithy, Justin Ahomadégbé, and Émile Derlin Zinsou dominating; the first 3 each represented a different area and ethnicity of the country. These 3 agreed to form a Presidential Council after violence marred the 1970 elections.

On 7 May 1972, Maga ceded power to Ahomadégbé. On 26 October 1972, Lt. Col. Mathieu Kérékou overthrew the ruling triumvirate, becoming president and stating that the country would not "burden itself by copying foreign ideology, and wants neither Capitalism, Communism, nor Socialism". On 30 November 1974, he announced that the country was officially Marxist, under control of the Military Council of the Revolution (CMR), which nationalized the petroleum industry and banks. On 30 November 1975, he renamed the country to the People's Republic of Benin.[30][31] The regime of the People's Republic of Benin underwent changes over the course of its existence: a nationalist period (1972-1974); a socialist phase (1974-1982); and a phase involving an opening to Western countries and economic liberalism (1982-1990).[32]

In 1974, under the influence of young revolutionaries - the "Ligueurs" - the government embarked on a socialist program: nationalization of strategic sectors of the economy, reform of the education system, establishment of agricultural cooperatives and new local government structures, and a campaign to eradicate "feudal forces" including tribalism. The regime banned opposition activities. Mathieu Kérékou was elected president by the National Revolutionary Assembly in 1980, re-elected in 1984. Establishing relations with China, North Korea, and Libya, he put "nearly all" businesses and economic activities under state control, causing foreign investment in Benin to dry up.[33] Kérékou attempted to reorganize education, pushing his own aphorisms such as "Poverty is not a fatality".[33] The regime financed itself by contracting to take nuclear waste, first from the Soviet Union and later from France.[33]

In the 1980s, Benin experienced higher economic growth rates (15.6% in 1982, 4.6% in 1983 and 8.2% in 1984), and the closure of the Nigerian border with Benin led to a drop in customs and tax revenues. The government was no longer able to pay civil servants' salaries.[32] In 1989, riots broke out when the regime did not have enough money to pay its army. The banking system collapsed. Eventually, Kérékou renounced Marxism, and a convention forced Kérékou to release political prisoners and arrange elections.[33] Marxism–Leninism was abolished as the nation's form of government.[34]

The country's name was officially changed to the Republic of Benin on 1 March 1990, after the newly formed government's constitution was completed.[35]

Kérékou lost to Nicéphore Soglo in a 1991 election and became the first President on the African mainland to lose power through an election.[36] Kérékou returned to power after winning the 1996 vote. In 2001, an election resulted in Kérékou winning another term, after which his opponents claimed election irregularities.[37] In 1999, Kérékou issued a national apology for the substantial role that Africans had played in the Atlantic slave trade.[38]

Kérékou and former president Soglo did not run in the 2006 elections, as both were barred by the constitution's restrictions on age and total terms of candidates.[39] On 5 March 2006, an election resulted in a runoff between Yayi Boni and Adrien Houngbédji. The runoff election was held on 19 March and was won by Boni,[40] who assumed office on 6 April.[41] Boni was reelected in 2011, taking 53.18% of the vote in the first round—enough to avoid a runoff election. He was the first president to win an election without a runoff since the restoration of democracy in 1991.[42]

In the March 2016 presidential elections in which Boni Yayi was barred by the constitution from running for a third term, businessman Patrice Talon won the second round with 65.37% of the vote, defeating investment banker and former Prime Minister Lionel Zinsou. Talon was sworn in on 6 April 2016.[43] Speaking on the same day that the Constitutional Court confirmed the results, Talon said that he would "first and foremost tackle constitutional reform", discussing his plan to limit presidents to a single term of 5 years in order to combat "complacency". He said that he planned to slash the size of the government from 28 to 16 members.[44] In April 2021, President Patrice Talon was re-elected, with more than 86.3% of the votes cast, in Benin's presidential election.[45] The change in election laws resulted in total control of parliament by president Talon's supporters.[46]

Politics

Its politics take place in a framework of a presidential representative democratic republic in which the President of Benin is both head of state and head of government, within a multi-party system. Executive power is exercised by the government. Legislative power is vested in the government and the legislature. The judiciary is officially independent of the executive and the legislature, while in practice its independence has been gradually hollowed out by Talon, and the Constitutional Court is headed by his former personal lawyer.[47] The political system is derived from the 1990 Constitution of Benin and the subsequent transition to democracy in 1991.

It was ranked 18th out of 52 African countries and scored best in the categories of Safety & Rule of Law and Participation & Human Rights.[48] In its 2007 Worldwide Press Freedom Index, Reporters Without Borders ranked Benin 53rd out of 169 countries. That place had fallen to 78th by 2016, when Talon took office, and has fallen further to 113th.[47] Benin has been rated equal-88th out of 159 countries in a 2005 analysis of police, business, and political corruption.[49]

Its democratic system "has eroded" since President Talon took office.[47] In 2018 his government introduced new rules for fielding candidates and raised the cost of registering. The electoral commission, packed with Talon's allies, barred all opposition parties from the parliamentary election in 2019, resulting in a parliament made up entirely of supporters of Talon. That parliament subsequently changed election laws such that presidential candidates need to have the approval of at least 10% of Benin's MPs and mayors. As parliament and most mayors' offices are controlled by Talon, he has control over who can run for president. These changes have drawn condemnation from international observers and led to the United States government partially terminating development assistance to the country.[50][51][52][53]

Administrative divisions

Benin is divided into 12 departments (French: départements) which are subdivided into 77 communes. In 1999, the previous 6 departments were each split into 2 halves, forming the later 12.[54]

| Map key | Department | Capital[55] | Population (2013) | Area (km2)[57] | Former Department |

Region | Sub-Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Alibori | Kandi | 868,046 | 26,242 | Borgou | North | North East |

| 1 | Atakora | Natitingou | 769,337 | 20,499 | Atakora | North | North West |

| 10 | Atlantique | Allada | 1,396,548 | 3,233 | Atlantique | South | South Centre |

| 4 | Borgou | Parakou | 1,202,095 | 25,856 | Borgou | North | North East |

| 5 | Collines | Dassa-Zoumé | 716,558 | 13,931 | Zou | North | North Centre |

| 6 | Kouffo | Aplahoué | 741,895 | 2,404 | Mono | South | South West |

| 3 | Donga | Djougou | 542,605 | 11,126 | Atakora | North | North West |

| 11 | Littoral | Cotonou | 678,874 | 79 | Atlantique | South | South Centre |

| 9 | Mono | Lokossa | 495,307 | 1,605 | Mono | South | South West |

| 12 | Ouémé | Porto-Novo | 1,096,850 | 1,281 | Ouémé | South | South East |

| 8 | Plateau | Pobè | 624,146 | 3,264 | Ouémé | South | South East |

| 7 | Zou | Abomey | 851,623 | 5,243 | Zou | North | North Centre |

Demographics

Ethnic Groups of Benin (2013 Census)

The majority of Benin's 11,485,000 inhabitants live in the south of the country. The life expectancy is 62 years.[58] About 42 African ethnic groups live in this country, including the Yoruba in the southeast (migrated from Nigeria in the 12th century); the Dendi in the north-central area (who came from Mali in the 16th century); the Bariba and the Fula in the northeast; the Betammaribe and the Somba in the Atakora Mountains; the Fon in the area around Abomey in the South Central and the Mina, Xueda, and Aja (who came from Togo) on the coast.[59]

Migrations have brought other African nationals to Benin that include Nigerians, Togolese, and Malians.[60] The foreign community includes Lebanese and Indians involved in trade and commerce.[60] The personnel of European embassies and foreign aid missions and of nongovernmental organisations and missionary groups account for a part of the 5,500 European population.[59] A part of the European population consists of Beninese citizens of French ancestry.

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1950 | 2000 | 2021 |

| Population[12][13] | 2,200,000 | 6,800,000 | 13,000,000 |

| ±% | — | +209.1% | +91.2% |

| Rank | Name | Department | Pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Cotonou  Porto-Novo |

1 | Cotonou | Littoral | 679,012 | |||||

| 2 | Porto-Novo | Ouémé | 264,320 | ||||||

| 3 | Parakou | Borgou | 255,478 | ||||||

| 4 | Godomey | Atlantique | 253,262 | ||||||

| 5 | Abomey-Calavi | Atlantique | 117,824 | ||||||

| 6 | Djougou | Donga | 94,773 | ||||||

| 7 | Bohicon | Zou | 93,744 | ||||||

| 8 | Ekpè | Ouémé | 75,313 | ||||||

| 9 | Abomey | Zou | 67,885 | ||||||

| 10 | Nikki | Borgou | 66,109 | ||||||

Religion

Religion in Benin (CIA World Factbook estimate 2013)[62]

In the 2013 census, 48.5% of the population of Benin were Christian (25.5% Roman Catholic, 6.7% Celestial Church of Christ, 3.4% Methodist, 12.9% other Christian denominations), 27.7% were Muslim, 11.6% practiced Vodun, 2.6% practiced other local traditional religions, 2.6% practiced other religions, and 5.8% claimed no religious affiliation.[1][63] A government survey conducted by the Demographic and Health Surveys Program in 2011-2012 indicated that followers of Christianity were 57.5% of the population (with Catholics making up 33.9%, Methodists 3.0%, Celestials 6.2% and other Christians 14.5%), while Muslims were 22.8%.[64]

Traditional religions include local animistic religions in the Atakora (Atakora and Donga provinces), and Vodun and Orisha veneration among the Yoruba and Tado peoples in the center and south of the nation. The town of Ouidah on the central coast is the spiritual center of Beninese Vodun.

The 2 largest religions are Christianity, followed throughout the south and center of Benin and in Otammari country in the Atakora, and Islam, introduced by the Songhai Empire and Hausa merchants, and followed throughout Alibori, Borgou and Donga provinces, and among the Yoruba (who also follow Christianity). Some continue to hold Vodun and Orisha beliefs and have incorporated the pantheon of Vodun and Orisha into Christianity. The Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, a Muslim sect originating in the 19th century, has a presence in the country.

Education

The literacy rate: in 2015 it was estimated to be 38.4% (49.9% for males and 27.3% for females).[58] Benin has achieved universal primary education and half of the children (54%) were enrolled in secondary education in 2013, according to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics.

While at a time the education system was not free,[65] Benin has abolished school fees and is carrying out the recommendations of its 2007 Educational Forum.[66] The government has devoted more than 4% of GDP to education since 2009. In 2015, public expenditure on education (all levels) amounted to 4.4% of GDP, according to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Within this expenditure, Benin devoted a share to tertiary education: 0.97% of GDP.[67]

Between 2009 and 2011, the share of people enrolled at university rose from 10% to 12% of the 18–25 year age cohort. Student enrollment in tertiary education more than doubled between 2006 and 2011 from 50,225 to 110,181. These statistics encompass not only bachelor's, master's and Ph.D. programmes but also students enrolled in non-degree post-secondary diplomas.[67]

Health

The HIV/AIDS rate in Benin was estimated in 2013 at 1.13% of adults aged 15–49 years.[68] Malaria is a problem in Benin, being a leading cause of morbidity and mortality among children younger than 5 years.[69]

During the 1980s, less than 30% of the country's population had access to primary health care services. Benin's infant mortality rate stood at 203 deaths for every 1000 live births. 1 in 3 mothers had access to child health care services. The Bamako Initiative changed that by introducing community-based healthcare reform, resulting in "more efficient and equitable" provision of services.[70] As of 2015, Benin had the 26th highest rate of maternal mortality in the world.[71] According to a 2013 UNICEF report, 13% of women had undergone female genital mutilation.[72] An approach strategy was extended to all areas of healthcare, with subsequent improvement in the health care indicators and improvement in health care efficiency and cost.[73] Demographic and Health Surveys has surveyed the issue in Benin since 1996.[74]

Geography

The north–south strip of land in West Africa lies between latitudes 6° and 13°N, and longitudes 0° and 4°E. It is bounded by Togo to the west, Burkina Faso and Niger to the north, Nigeria to the east, and the Bight of Benin to the south. The distance from the Niger River in the north to the Atlantic Ocean in the south is about 650 km (404 mi). Although the coastline measures 121 km (75 mi), the country measures about 325 km (202 mi) at its widest point. 4 terrestrial ecoregions lie within Benin's borders: Eastern Guinean forests, Nigerian lowland forests, Guinean forest-savanna mosaic, and West Sudanian savanna.[75] It had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 5.86/10, ranking it 93rd globally out of 172 countries.[76]

Benin shows some variation in elevation and can be divided into 4 areas from the south to the north, starting with the lower-lying, sandy, coastal plain (highest elevation 10 m (32.8 ft)) which is, at most, 10 km (6.2 mi) wide. It is marshy and dotted with lakes and lagoons communicating with the ocean. Behind the coast lies the Guinean forest-savanna mosaic-covered plateaus of southern Benin (altitude between 20 and 200 m (66 and 656 ft)), which are split by valleys running north to south along the Couffo, Zou, and Ouémé Rivers.

This geography makes it vulnerable to climate change. With the majority of the country living near the coast in lower-lying areas sea level rise could have effects on the economy and population.[77] Northern areas will see additional regions become deserts.[78] An area of flatter land dotted with rocky hills whose altitude reaches 400 m (1,312 ft) extends around Nikki and Save.

A range of mountains extends along the northwest border and into Togo; these are the Atacora. The highest point, Mont Sokbaro, is at 658 m (2,159 ft). Benin has fields, mangroves, and remnants of forests. In the rest of the country, the savanna is covered with thorny scrub and dotted with baobab trees. Some forests line the banks of rivers. In the north and the northwest of Benin, the Reserve du W du Niger and Pendjari National Park has elephants, lions, antelopes, hippos, and monkeys.[59] Pendjari National Park together with the bordering Parks Arli and W in Burkina Faso and Niger are among the strongholds for the endangered West African lion. With an estimated 356 (range: 246–466) lions, W-Arli-Pendjari harbors the largest remaining population of lions in West Africa.[79] Historically Benin has served as habitat for the endangered painted hunting dog, Lycaon pictus;[80] this canid is thought to have been locally extirpated.

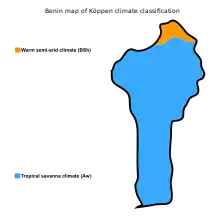

Annual rainfall in the coastal area averages 1300 mm or about 51 inches. Benin has 2 rainy and 2 dry seasons per year. The principal rainy season is from April to late July, with a shorter less intense rainy period from September to November. The main dry season is from December to April, with a cooler dry season from July to September. Temperatures and humidity are higher along the tropical coast. In Cotonou, the average maximum temperature is 31 °C (87.8 °F); the minimum is 24 °C (75.2 °F).[59]

Variations in temperature increase when moving north through savanna and plateau toward the Sahel. A dry wind from the Sahara called the Harmattan blows from December to March, when grass dries up, other vegetation turns reddish brown, and a veil of fine dust hangs over the country, causing the skies to be "overcast". It is also the season when farmers burn brush in the fields.[59]

Economy

.svg.png.webp)

The economy is dependent on subsistence agriculture, cotton production, and regional trade. Cotton accounts for 40% of the GDP and roughly 80% of official export receipts.[81]

Real GDP growth was estimated at 5.1 and 5.7% in 2008 and 2009, respectively. The main driver of growth is the agricultural sector, with cotton being the main export, while services continue to contribute the largest part of GDP mostly because of Benin's geographical location, enabling trade, transportation, transit and tourism activities with its neighboring states.[82] Benin's overall macroeconomic conditions were "positive" in 2017, with a growth rate of around 5.6%. Economic growth was mostly driven by the cotton industry and other cash crops, the Port of Cotonou, and telecommunications. A source of revenue is the Port of Cotonou, and the government is seeking to expand its revenue base. In 2017, Benin imported about $2.8 billion in goods such as rice, meat and poultry, alcoholic beverages, fuel plastic materials, specialized mining and excavating machinery, telecommunications equipment, passenger vehicles, and toiletries and cosmetics. Principal exports are ginned cotton, cotton cake and cotton seeds, cashew, shea butter, cooking oil, and lumber.[83]

Access to biocapacity is lower than world average. In 2016, Benin had 0.9 global hectares [84] of biocapacity per person within its territory, less than the world average of 1.6 global hectares per person.[85] In 2016 Benin used 1.4 global hectares of biocapacity per person - their ecological footprint of consumption. This means they use "slightly under double" as much biocapacity as Benin contains. As a result, Benin is running a biocapacity deficit.[84]

In order to raise growth still further, Benin plans to attract more foreign investment, place more emphasis on tourism, facilitate the development of new food processing systems and agricultural products, and encourage new information and communication technology. Projects to improve the business climate by reforms to the land tenure system, the commercial justice system, and the financial sector were included in Benin's US$307 million Millennium Challenge Account grant signed in February 2006.[86]

The Paris Club and bilateral creditors have eased the external debt situation, with Benin benefiting from a G8 debt reduction announced in July 2005, while pressing for more rapid structural reforms. An "insufficient" electrical supply continues to "adversely affect" Benin's economic growth and the government has taken steps to increase domestic power production.[58]

While trade unions in Benin represent up to 75% of the formal workforce, the informal economy has been noted by the International Trade Union Confederation (ITCU) to contain ongoing problems, including a lack of women's wage equality, the use of child labor, and the continuing issue of forced labor.[87] Benin is a member of the Organization for the Harmonization of Business Law in Africa (OHADA).[88]

Cotonou has the country's only seaport and international airport. Benin is connected by 2-lane asphalted roads to its neighboring countries (Togo, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Nigeria). Mobile telephone service is available across the country through operators. ADSL connections are available in some areas. Benin is connected to the Internet by way of satellite connections (since 1998) and a single submarine cable SAT-3/WASC (since 2001). Relief of "high price" is expected with the initiation of the Africa Coast to Europe cable in 2011.

With the GDP growth rate of 4-5% remaining consistent over 2 decades, poverty has been increasing.[89] According to the National Institute of Statistics and Economic Analysis in Benin, those living under the poverty line have increased from 36.2% in 2011 to 40.1% in 2015.[90]

National policy framework

The Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research is responsible for implementing science policy. The National Directorate of Scientific and Technological Research handles planning and coordination whereas the National Council for Scientific and Technical Research and National Academy of Sciences, Arts, and Letters each play an advisory role. Financial support comes from Benin's National Fund for Scientific Research and Technological Innovation. The Benin Agency for the Promotion of Research Results and Technological Innovation carries out technology transfer through the development and dissemination of research results.[67] Benin was ranked 128th in the Global Innovation Index in 2021, down from 123rd in 2019.[91][92][93][94]

The regulatory framework has evolved since 2006 when the a science policy was prepared. This has been updated and complemented by new texts on science and innovation (the year of adoption is between brackets):[67]

- a manual for monitoring and evaluating research structures and organizations (2013);

- a manual on how to select research programmes and projects and apply to the National Fund for Scientific Research and Technological Innovation (2013) for competitive grants;

- a draft act for funding scientific research and innovation and a draft code of ethics for scientific research and innovation were both submitted to the Supreme Court in 2014;

- a strategic plan for scientific research and innovation (under development in 2015).

Equally important are Benin's efforts to integrate science into existing policy documents:

- Benin Development Strategies 2025: Benin 2025 Alafia (2000);

- Growth Strategy for Poverty Reduction 2011–2016 (2011);

- Phase 3 of the Ten-year Development Plan for the Education Sector, covering 2013–2015;

- Development Plan for Higher Education and Scientific Research 2013–2017 (2014).

In 2015, Benin's priority areas for scientific research were: health, education, construction and building materials, transportation and trade, culture, tourism and handicrafts, cotton/textiles, food, energy and climate change.[67]

Some so-called challenges facing research and development in Benin are:[67]

- the unfavorable organizational framework for research: weak governance, a lack of co-operation between research structures and the absence of an official document on the status of researchers;

- the inadequate use of human resources and the lack of any motivational policy for researchers; and

- the mismatch between research and development needs.

Human and financial investment in research

In 2007, Benin counted 1,000 researchers (in headcounts). This corresponds to 115 researchers per million inhabitants. The "main research structures" are the Centre for Scientific and Technical Research, National Institute of Agricultural Research, National Institute for Training and Research in Education, Office of Geological and Mining Research and the Centre for Entomological Research.[67]

The University of Abomey-Calavi was selected by the World Bank in 2014 to participate in its Centres of Excellence project, owing to its expertise in applied mathematics. Within this project, the World Bank has loaned $8 million to Benin. The Association of African Universities has received funds to enable it to co-ordinate knowledge-sharing among the 19 universities in West Africa involved in the project.[67]

There are "no available data" on Benin's level of investment in research and development.[67]

In 2013, the government devoted 2.5% of GDP to public health. In December 2014, 150 volunteer health professionals travelled to Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone from Benin, Côte d'Ivoire, Ghana, Mali, Niger, and Nigeria, as part of a joint initiative by the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and its specialized agency, the West African Health Organisation, to help combat the epidemic. The Ebola epidemic has been a reminder of the underinvestment in West African health systems.[67]

The Government of Benin devoted less than 5% of GDP to agricultural development in 2010, while the members of the African Union had agreed to commit at least 10% of GDP to this area in the Maputo Declaration of 2003. They reiterated this goal in the Malabo Declaration adopted in Equatorial Guinea in 2014. In the latter declaration, they reaffirmed their 'intention to devote 10% of their national budgets to agricultural development and agreed to targets such as doubling agricultural productivity, halving post-harvest loss and bringing stunting down to 10% across Africa'. African leaders meeting in Equatorial Guinea failed to resolve the debate on establishing a common standard of measurement for the 10% target.[95]

Research output

Benin has the third-highest publication intensity for scientific journals in West Africa, according to Thomson Reuters' Web of Science, Science Citation Index Expanded. There were 25.5 scientific articles per million inhabitants cataloged in this database in 2014. This compares with 65.0 for the Gambia, 49.6 for Cape Verde, 23.2 for Senegal and 21.9 for Ghana. The volume of publications in this database tripled in Benin between 2005 and 2014 from 86 to 270. Between 2008 and 2014, Benin's "main scientific collaborators" were based in France (529 articles), United States (261), United Kingdom (254), Belgium (198) and Germany (156).[67]

Transportation

Transport in Benin includes road, rail, water and air transportation. Benin possesses a total of 6,787 km of highway, of which 1,357 km are paved. Of the paved highways in the country, there are 10 expressways. This leaves 5,430 km of unpaved road. The Trans-West African Coastal Highway crosses Benin, connecting it to Nigeria to the east, and Togo, Ghana and Ivory Coast to the west. When construction in Liberia and Sierra Leone is finished, the highway will continue west to 7 other Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) nations. A paved highway connects Benin northwards to Niger, and through that country to Burkina Faso and Mali to the north-west.

Rail transport in Benin consists of 578 km (359 mi) of single track, 1,000 mm (3 ft 3+3⁄8 in) metre gauge railway. Construction work has commenced on international lines connecting Benin with Niger and Nigeria, with outline plans announced for further connections to Togo and Burkina Faso. Benin will be a participant in the AfricaRail project.

Cadjehoun Airport, located at Cotonou, has direct international jet service to Accra, Niamey, Monrovia, Lagos, Ouagadougou, Lomé, and Douala, and other cities in Africa. Direct services link Cotonou to Paris, Brussels, and Istanbul.

Culture

Arts

Beninese literature had an oral tradition before French became the dominant language.[96] Félix Couchoro wrote the first Beninese novel, L'Esclave (The Slave), in 1929.

Post-independence, native folk music was combined with Ghanaian highlife, French cabaret, American rock, funk and soul, and Congolese rumba.

Biennale Benin, continuing the projects of some organizations and artists, started in the country in 2010 as a collaborative event called "Regard Benin". In 2012, the project became a Biennial coordinated by the Consortium, a federation of local associations. The international exhibition and artistic program of the 2012 Biennale Benin are curated by Abdellah Karroum and the Curatorial Delegation.

Customary names

Some Beninese in the south of the country have Akan-based names indicating the day of the week on which they were born. This is due to influence of the Akan people such as the Akwamu and others.[97]

Language

Local languages are used as the languages of instruction in elementary schools, with French introduced after years. At the secondary school level, French is the sole language of instruction. Beninese languages are "generally transcribed" with a separate letter for each speech sound (phoneme), rather than using diacritics as in French or digraphs as in English. This includes Beninese Yoruba, which in Nigeria is written with both diacritics and digraphs. For instance, the mid vowels written é, è, ô, o in French are written e, ɛ, o, ɔ in Beninese languages, whereas the consonants are written ng and sh or ch in English are written ŋ and c. Digraphs are used for nasal vowels and the labial-velar consonants kp and gb, as in the name of the Fon language Fon gbe /fõ ɡ͡be/, and diacritics are used as tone marks. In French-language publications, a mixture of French and Beninese orthographies may be seen.

Cuisine

The cuisine involves fresh meals served with a variety of key sauces. In southern Benin cuisine, an ingredient is corn which has been used to prepare dough which has been served with peanut- or tomato-based sauces. Fish and chicken, beef, goat, and bush rat are consumed. A staple in northern Benin is yams which has been served with sauces mentioned above. The population in the northern provinces use beef and pork meat which is fried in palm or peanut oil or cooked in sauces. Cheese is used in some dishes. Couscous, rice, and beans are eaten, along with fruits such as mangoes, oranges, avocados, bananas, kiwi fruit, and pineapples.

Meals are said to be generally light on meat and generous on vegetable fat. Frying in palm or peanut oil is a meat preparation, and smoked fish is prepared in Benin. Grinders are used to prepare corn flour, which is made into a dough and served with sauces. "Chicken on the spit" is a recipe in which chicken is roasted over a fire on wooden sticks. Palm roots are sometimes soaked in a jar with salt water and sliced garlic to tenderize them, then used in dishes. Some people have outdoor mud stoves for cooking.

Traditional authorities

Benin has numerous non-sovereign monarchies within the country, many of them derivative of pre-colonial kingdoms (such as Arda). Non-sovereign monarchs do not have an official, constitutional role, and are largely ceremonial and subservient to political and civil authorities. Despite this, they play an influential role in local political matters within their particular realms and are often courted by Beninese politicians for electoral support. Advocacy groups such as the High Council of Kings of Benin represent the monarchs nationally.[99][100]

See also

- Index of Benin-related articles

- Outline of Benin

- Telephone numbers in Benin

References

- "PRINCIPAUX INDICATEURS SOCIO DEMOGRAPHIQUES ET ECONOMIQUES" (PDF). www.insae-bj.org (in French). INSTITUT NATIONAL DE LA STATISTIQUE ET DE L'ANALYSE ECONOMIQUE. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 September 2020. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- "Benin". United States Department of State. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- "Benin Population 2022 (Demographics, Maps, Graphs)". worldpopulationreview.com. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- Annuaire statistique 2010 (PDF) (Report) (in French). INSAE. 2012. p. 49. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- "Benin". The World Factbook (2022 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2018". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Archived from the original on 12 June 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- "GINI index (World Bank estimate)". databank.worldbank.org. World Bank. Archived from the original on 4 September 2022. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- Human Development Report 2020 The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 15 December 2020. pp. 343–346. ISBN 978-92-1-126442-5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 January 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- Jones, Daniel (2011). Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (eds.). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6.

- "Dahomey Announces Its Name Will Be Benin". The New York Times. 1 December 1975. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 16 September 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- Hughes, R. H.; Hughes, J. S. (1992). A Directory of African Wetlands. IUCN. p. 301. ISBN 978-2-88032-949-5. Archived from the original on 8 May 2016. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- "World Population Prospects 2022". population.un.org. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- "World Population Prospects 2022: Demographic indicators by region, subregion and country, annually for 1950-2100" (XSLX). population.un.org ("Total Population, as of 1 July (thousands)"). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- "FAO Initiative on Soaring Food Prices". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Archived from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- Global Logistics Assessments Reports Handbook. Vol. 1: Strategic Transportation and Customs Information for Selected Countries. International Business Publications USA. 2008 [2015-10-06]. p. 85. ISBN 978-0739766033.

- Bay, Edna (1998). Wives of the Leopard: Gender, Politics, and Culture in the Kingdom of Dahomey. University of Virginia Press.

- Akinjogbin, I.A. (1967). Dahomey and Its Neighbors: 1708–1818. Cambridge University Press. OCLC 469476592.

- Law, Robin (1986). "Dahomey and the Slave Trade: Reflections on the Historiography of the Rise of Dahomey". The Journal of African History. 27 (2): 237–267. doi:10.1017/s0021853700036665. S2CID 165754199.

- Creevey, Lucy; Ngomo, Paul; Vengroff, Richard (2005). "Party Politics and Different Paths to Democratic Transitions: A Comparison of Benin and Senegal". Party Politics. 11 (4): 471–493. doi:10.1177/1354068805053213. S2CID 145169455. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- Harms, Robert W. (2002). The Diligent: A Voyage Through the Worlds of the Slave Trade. Basic Books. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-465-02872-6. Archived from the original on 9 May 2016. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- Alpern, Stanley B. (1998). Amazons of Black Sparta: The Women Warriors of Dahomey. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-85065-362-2. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- Miller, David Lee (10 July 2003). "African Ambassador Apologizes for Slavery Role". Fox News. Archived from the original on 22 May 2010.

- "African Slave Owners". The story of South Africa: Slavery. BBC World Service. Archived from the original on 8 March 2013.

- Manning, Patrick (1982). Slavery, Colonialism and Economic Growth in Dahomey, 1640–1960. London: Cambridge University Press. pp. 15–16.

- "This ivory relic reveals the colonial power dynamic between Benin and Portugal History Magazine, National Geographic, 09.02.2021". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 9 February 2021. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- Manning, Patrick (1982). Slavery, Colonialism and Economic Growth in Dahomey, 1640-1960. Cambridge University Press. p. 15. ISBN 9780511563072.

- "President Sirleaf congratulates Benin on 57th Independence Anniversary". Agence de Presse Africane. 31 July 2017. Archived from the original on 30 July 2018. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- Stokes, Jamie, ed. (2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East: L to Z. Infobase Publishing. p. 229. ISBN 978-0-8160-7158-6. Archived from the original on 3 May 2016. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- Araujo, Ana Lucia (2010). Public Memory of Slavery: Victims and Perpetrators in the South Atlantic. Cambria Press. p. 111. ISBN 978-1-60497-714-1. Archived from the original on 17 June 2016. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- Dickovick, J. Tyler (9 August 2012). Africa 2012. Stryker Post. p. 69. ISBN 978-1-61048-882-2. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- Houngnikpo, Mathurin C.; Decalo, Samuel (14 December 2012). Historical Dictionary of Benin. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-8108-7171-7. Archived from the original on 23 April 2014. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- "Wikiwix[archive]". Archived from the original on 4 March 2021. Retrieved 11 December 2021.

- Kneib, Martha (7 January 2007). Benin. pp. 22–25. ISBN 978-0-7614-2328-7.

- "A Short History of the People's Republic of Benin (1974–1990)". Socialist.net. 27 August 2008. Archived from the original on 23 April 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- "Benin". Flagspot.net. Archived from the original on 12 June 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- "Official Result in Benin Vote Shows Big Loss for Kerekou". The New York Times. 26 March 1991. Archived from the original on 1 June 2022. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- "ben007 President Kerekou re-elected in Benin". www.afrol.com. Archived from the original on 1 June 2022. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- Gates, Henry Louis, "Ending the Slavery Blame-Game Archived 7 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine". The New York Times, 22 April 2010

- "President Mathieu Kerekou leaves after 29 years". The New Humanitarian (in French). 7 April 2006. Archived from the original on 1 June 2022. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- "Boni wins Benin presidential election: official". ABC News. 22 March 2006. Archived from the original on 1 June 2022. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- "Celebration As Boni Takes Over". Archived from the original on 18 April 2006. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- "Benin's Boni Yayi wins second term - court". Reuters. 21 March 2011. Archived from the original on 1 June 2022. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- "Businessman sworn in as Benin's president". Reuters. 6 April 2016. Archived from the original on 17 April 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- "Newly-elected Benin president aims to reduce presidential terms". Reuters. 26 March 2016. Archived from the original on 3 May 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- "Benin's president wins re-election in preliminary results". ABC News. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- "Benin vote count begins after opposition groups boycott election". www.aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 19 April 2021. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- "Benin's democratic beacon dims". The Economist. Archived from the original on 12 April 2021. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- "2014 Ibrahim Index of African Governance (IIAG)". Mo Ibrahim Foundation. 2014. Archived from the original on 30 May 2013. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- "Countries Compared by Government, Government corruption rating. International Statistics at NationMaster.com". nationmaster.com. Archived from the original on 8 February 2011. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- "Benin: Freedom in the World 2021 Country Report". Freedom House. Archived from the original on 16 December 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- "Press Release: MCC's Board Selects Belize, Zambia for Grant Assistance". Millennium Challenge Corporation. Archived from the original on 15 December 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

However, due to Benin's overall multi-year decline in its commitment to MCC's eligibility criteria and the principles of democratic governance, the Board discussed and endorsed MCC's determination to significantly reduce the portion of the planned regional investment that would be made in Benin through a concurrent compact.

- "Recul de la démocratie: les Etats-Unis sanctionnent le Bénin à travers le MCC". La Nouvelle Tribune (in French). 16 December 2021. Archived from the original on 16 December 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- Hirschel-Burns, Tim. "Benin's King of Cotton Makes Its Democracy a Sham". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 16 December 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- Statoids - Benin, archived from the original on 18 May 2021, retrieved 26 November 2019

- Communiqué du Conseil des Ministres du 22 Juin 2016 | Portail Officiel du Gouvernement Béninois Archived 2019-01-25 at the Wayback Machine. Gouv.bj (22 June 2016). Retrieved on 2017-01-02.

- Bénin : liste des 12 nouveaux préfets et des chefs-lieux de départements Archived 2016-11-20 at the Wayback Machine. Lanouvelletribune.info. Retrieved on 2017-01-02.

- Benin. Geohive.com. Retrieved on 2017-01-02.

- "Benin". The World Factbook (2022 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

-

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Background Note: Benin". U.S. Department of State. June 2008. Archived from the original on 4 June 2019. Retrieved 22 May 2019..

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Background Note: Benin". U.S. Department of State. June 2008. Archived from the original on 4 June 2019. Retrieved 22 May 2019.. - "Benin Population". worldpopulationreview.com. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- "Benin: Departments, Major Cities & Towns - Population Statistics, Maps, Charts, Weather and Web Information". www.citypopulation.de. Archived from the original on 9 May 2019. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- "Benin". The World Factbook (2022 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 6 November 2008. (Archived 2008 edition)

- International Religious Freedom Report 2007: Benin Archived 29 July 2019 at the Wayback Machine . United States Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (14 September 2007). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- "Enquête Démographique et de Santé (EDSB-IV) 2011-2012" (PDF) (in French). Ministère du Développement, de l'Analyse Économique et de la Prospective Institut National de la Statistique et de l'Analyse Économique (INSAE). p. 39. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 June 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- "Benin". Country Reports on Human Rights Practices. U. S. Department of State. 23 February 2001. Archived from the original on 5 June 2019. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- "Benin". U. N. Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Archived from the original on 13 September 2010. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- Essegbey, George; Diaby, Nouhou; Konté, Almamy (2015). West Africa. In: UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030 (PDF). Paris: UNESCO. pp. 471–497. ISBN 978-92-3-100129-1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- "HIV/AIDS—Adult Prevalence Rate". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 21 December 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- "Malaria in Benin". malaria.com. 24 February 2011. Archived from the original on 22 January 2015. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- "Bamako Initiative revitalizes primary health care in Benin". WHO.int. Archived from the original on 6 January 2007. Retrieved 28 December 2006.

- "Maternal Mortality Rate". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 18 April 2015. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: A statistical overview and exploration of the dynamics of change (PDF) (Report). United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). July 2013. p. 27. ISBN 978-92-806-4703-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 April 2015.

- Knippenberg, R; Alihonou, E; Soucat, A; Oyegbite, K; Calivis, M; Hopwood, I; Niimi, R; Diallo, MP; Conde, M; Ofosu-Amaah, S (1997). "Implementation of the Bamako Initiative: strategies in Benin and Guinea". Int J Health Plann Manage. 12 Suppl 1 (S1): S29-47. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1751(199706)12:1+<S29::AID-HPM465>3.0.CO;2-U. PMID 10173105.

- "Benin". The DHS Program. USAID. Archived from the original on 27 August 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- Dinerstein, Eric; Olson, David; Joshi, Anup; Vynne, Carly; Burgess, Neil D.; Wikramanayake, Eric; Hahn, Nathan; Palminteri, Suzanne; Hedao, Prashant; Noss, Reed; Hansen, Matt; Locke, Harvey; Ellis, Erle C; Jones, Benjamin; Barber, Charles Victor; Hayes, Randy; Kormos, Cyril; Martin, Vance; Crist, Eileen; Sechrest, Wes; Price, Lori; Baillie, Jonathan E. M.; Weeden, Don; Suckling, Kierán; Davis, Crystal; Sizer, Nigel; Moore, Rebecca; Thau, David; Birch, Tanya; Potapov, Peter; Turubanova, Svetlana; Tyukavina, Alexandra; de Souza, Nadia; Pintea, Lilian; Brito, José C.; Llewellyn, Othman A.; Miller, Anthony G.; Patzelt, Annette; Ghazanfar, Shahina A.; Timberlake, Jonathan; Klöser, Heinz; Shennan-Farpón, Yara; Kindt, Roeland; Lillesø, Jens-Peter Barnekow; van Breugel, Paulo; Graudal, Lars; Voge, Maianna; Al-Shammari, Khalaf F.; Saleem, Muhammad (2017). "An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm". BioScience. 67 (6): 534–545. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix014. ISSN 0006-3568. PMC 5451287. PMID 28608869.

- Grantham, H. S.; Duncan, A.; Evans, T. D.; Jones, K. R.; Beyer, H. L.; Schuster, R.; Walston, J.; Ray, J. C.; Robinson, J. G.; Callow, M.; Clements, T.; Costa, H. M.; DeGemmis, A.; Elsen, P. R.; Ervin, J.; Franco, P.; Goldman, E.; Goetz, S.; Hansen, A.; Hofsvang, E.; Jantz, P.; Jupiter, S.; Kang, A.; Langhammer, P.; Laurance, W. F.; Lieberman, S.; Linkie, M.; Malhi, Y.; Maxwell, S.; Mendez, M.; Mittermeier, R.; Murray, N. J.; Possingham, H.; Radachowsky, J.; Saatchi, S.; Samper, C.; Silverman, J.; Shapiro, A.; Strassburg, B.; Stevens, T.; Stokes, E.; Taylor, R.; Tear, T.; Tizard, R.; Venter, O.; Visconti, P.; Wang, S.; Watson, J. E. M. (2020). "Anthropogenic modification of forests means only 40% of remaining forests have high ecosystem integrity - Supplementary Material". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 5978. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19493-3. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7723057. PMID 33293507.

- "Benin | UNDP Climate Change Adaptation". www.adaptation-undp.org. Archived from the original on 5 August 2020. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- "Climate Change Profile: Benin" (PDF). Netherlands Commission for Environmental Assessment. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- Henschel, P.; Coad, L.; Burton, C.; Chataigner, B.; Dunn, A.; MacDonald, D.; Saidu, Y.; Hunter, L. T. B. (2014). Hayward, Matt (ed.). "The Lion in West Africa is Critically Endangered". PLoS ONE. 9 (1): e83500. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...983500H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0083500. PMC 3885426. PMID 24421889.

- Hogan, C. Michael (2 December 2008). N. Stromberg (ed.). "Painted Hunting Dog: Lycaon pictus". GlobalTwitcher. Archived from the original on 9 December 2010.

- "Background Note: Benin". State.gov. 3 February 2010. Archived from the original on 4 June 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- "Benin: Financial Sector Overview". Making Finance Work for Africa. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 30 November 2010.

-

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Benin - Market Overview | Privacy Shield". www.privacyshield.gov. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Benin - Market Overview | Privacy Shield". www.privacyshield.gov. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 29 December 2020. - "Country Trends". Global Footprint Network. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- Lin, David; Hanscom, Laurel; Murthy, Adeline; Galli, Alessandro; Evans, Mikel; Neill, Evan; Mancini, MariaSerena; Martindill, Jon; Medouar, FatimeZahra; Huang, Shiyu; Wackernagel, Mathis (2018). "Ecological Footprint Accounting for Countries: Updates and Results of the National Footprint Accounts, 2012-2018". Resources. 7 (3): 58. doi:10.3390/resources7030058.

- "2006 Benin Compact Summary" (PDF). Millennium Challenge Corporation. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 February 2016. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- "Serious violations of core labour standards in Benin, Burkina Faso and Mali". ICFTU Online. Archived from the original on 4 September 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2007.

- "OHADA.com: The business law portal in Africa". Archived from the original on 26 March 2009. Retrieved 22 March 2009.

- "The World Bank In Benin". The World Bank. 10 October 2017. Archived from the original on 9 March 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- International Monetary Fund. African Dept. (2017). Benin: Request for a Three-year Arrangement Under the Extended Credit Facility-Press Release; Staff Report; and Statement by the Executive Director for Benin. International Monetary Fund. p. 5.

- "Global Innovation Index 2021". World Intellectual Property Organization. United Nations. Archived from the original on 20 September 2021. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- "Global Innovation Index 2019". www.wipo.int. Archived from the original on 2 September 2021. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- "RTD - Item". ec.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 2 September 2021. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- "Global Innovation Index". INSEAD Knowledge. 28 October 2013. Archived from the original on 2 September 2021. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- "One Applauds AU Malabo Declaration's Recommitment to Agriculture Transformation". ONE.org. 2 July 2014. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- "Benin". Archived from the original on 13 August 2011. Retrieved 30 July 2007.

- Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica (2000). "Akwamu: historical state, Africa". Archived copy. Encyclopaedia Britannica Online. Archived from the original on 29 April 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Mozey, Brian (22 June 2016). "Duo develops nonprofit organization, Baseball in Benin". Minnesota Sun Post. APG of East Central Minnesota. Archived from the original on 5 August 2016. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- Research Directorate (4 May 2016). Benin: Kings in northern Benin, specifically in Borgou department; extent of their power in comparison with the power of political and civil authorities; a king's ability to force a woman to marry him; remedies available to a woman who refuses to marry a king (2014-April 2016) (Response to Information Request). Ottawa: Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada. BEN105509.FE. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 27 August 2022 – via European Country of Origin Information Network.

- "Monde: Haïti veut punir les crimes vaudous comme au Benin". Anmwe News (in French). Archived from the original on 27 August 2022. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

![]() This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY-SA IGO 3.0 Text taken from UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030, 471–497, UNESCO, UNESCO Publishing.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY-SA IGO 3.0 Text taken from UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030, 471–497, UNESCO, UNESCO Publishing.

Further reading

- Butler, S., Benin (Bradt Travel Guides) (Bradt Travel Guides, 2019)

- Caulfield, Annie, Show Me the Magic: Travels Round Benin by Taxi (Penguin Books Ltd, 2003)

- Kraus, Erika and Reid, Felice, Benin (Other Places Travel Guide) (Other Places Publishing, 2010)

- Seely, Jennifer, The Legacies of Transition Governments in Africa: The Cases of Benin and Togo (Palgrave Macmillan, 2009)

External links

- Country Profile from BBC News

- Benin. The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- Benin from UCB Libraries GovPubs

- BBC, Civilisations - BBC Two: "Western reactions to Benin bronzes" on YouTube, Apr 10, 2018.

- Benin at Curlie

- commons:Atlas of Benin

- Benin Exports

- Forecasts for Benin Development

Government

- Government of Benin (official website) (in French)

- Chief of State and Cabinet Members

- Global Integrity Report: Benin

News media

- Directory of Benin news sources from Stanford University

Trade

Sports

.svg.png.webp)