Rhinoceros

A rhinoceros (/raɪˈnɒsərəs/; from Ancient Greek ῥῑνόκερως (rhīnókerōs) 'nose-horned'; from ῥῑνός (rhīnós) 'nose', and κέρας (kéras) 'horn'[1]), commonly abbreviated to rhino, is a member of any of the five extant species (or numerous extinct species) of odd-toed ungulates in the family Rhinocerotidae. (It can also refer to a member of any of the extinct species of the superfamily Rhinocerotoidea.) Two of the extant species are native to Africa, and three to South and Southeast Asia.

| Rhinoceros Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

| Rhinoceros species of different genera; from top-left, clockwise: White rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum), Sumatran rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis), Indian rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis), Black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Superfamily: | Rhinocerotoidea |

| Family: | Rhinocerotidae Owen, 1845 |

| Type genus | |

| Rhinoceros Linnaeus, 1758 | |

| Extant and subfossil genera | |

|

Ceratotherium | |

| |

| Rhinoceros range | |

Rhinoceroses are some of the largest remaining megafauna: all weigh at least one tonne in adulthood. They have a herbivorous diet, small brains (400–600 g) for mammals of their size, one or two horns, and a thick (1.5–5 cm), protective skin formed from layers of collagen positioned in a lattice structure. They generally eat leafy material, although their ability to ferment food in their hindgut allows them to subsist on more fibrous plant matter when necessary. Unlike other perissodactyls, the two African species of rhinoceros lack teeth at the front of their mouths; they rely instead on their lips to pluck food.[2]

Rhinoceros are killed by poachers for their horns, which are bought and sold on the black market for high prices, leading to most living rhinoceros species being considered endangered. The contemporary market for rhino horn is overwhelmingly driven by China and Vietnam, where it is bought by wealthy consumers to use in traditional Chinese medicine, among other uses. Rhino horns are made of keratin, the same material as hair and fingernails, and there is no good evidence of any health benefits.[3][4][5] A market also exists for rhino horn dagger handles in Yemen, which was the major source of demand for rhino horn in the 1970s and 1980s.[6]

Taxonomy and naming

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cladogram following a phylogenetic study.[7] |

The word rhinoceros is derived through Latin from the Ancient Greek: ῥῑνόκερως, which is composed of ῥῑνο- (rhino-, "nose") and κέρας (keras, "horn") with a horn on the nose. The plural in English is rhinoceros or rhinoceroses. The collective noun for a group of rhinoceroses is crash or herd. The name has been in use since the 14th century.[8]

The family Rhinocerotidae consists of only four extant genera: Ceratotherium (white rhinoceros), Diceros (black rhinoceros), Dicerorhinus (Sumatran rhinoceros), and Rhinoceros (Indian and Javan rhinoceros). The living species fall into three categories. The two African species, the white rhinoceros and the black rhinoceros, belong to the tribe Dicerotini, which originated in the middle Miocene, about 14.2 million years ago. The species diverged during the early Pliocene (about 5 million years ago). The main difference between black and white rhinos is the shape of their mouths – white rhinos have broad flat lips for grazing, whereas black rhinos have long pointed lips for eating foliage. There are two living Rhinocerotini species, the Indian rhinoceros and the Javan rhinoceros, which diverged from one another about 10 million years ago. The Sumatran rhinoceros is the only surviving representative of the Dicerorhinini.[9]

A subspecific hybrid white rhino (Ceratotherium s. simum × C. s. cottoni) was bred at the Dvůr Králové Zoo (Zoological Garden Dvur Kralove nad Labem) in the Czech Republic in 1977. Interspecific hybridisation of black and white rhinoceros has also been confirmed.[10]

While the black rhinoceros has 84 chromosomes (diploid number, 2N, per cell), all other rhinoceros species have 82 chromosomes. Chromosomal polymorphism might lead to varying chromosome counts. For instance, in a study there were three northern white rhinoceroses with 81 chromosomes.[11]

Species

White

There are two subspecies of white rhinoceros: the southern white rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum simum) and the northern white rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum cottoni). As of 2013, the southern subspecies has a wild population of 20,405—making them the most abundant rhino subspecies in the world. The northern subspecies is critically endangered, with all that is known to remain being two captive females. There is no conclusive explanation of the name "white rhinoceros". A popular idea that "white" is a distortion of either the Afrikaans word wyd or the Dutch word wijd (or its other possible spellings whyde, weit, etc.,), meaning "wide" and referring to the rhino's square lips, is not supported by linguistic studies.[12][13]

The white rhino has an immense body and large head, a short neck and broad chest. Females weigh 1,600 kg (4,000 lb) and males 2,400 kg (5,000 lb). The head-and-body length is 3.5–4.6 m (11–15 ft) and the shoulder height is 1.8–2 m (5.9–6.6 ft). On its snout it has two horns. The front horn is larger than the other horn and averages 90 cm (35 in) in length and can reach 150 cm (59 in). The white rhinoceros also has a prominent muscular hump that supports its relatively large head. The colour of this animal can range from yellowish brown to slate grey. Most of its body hair is found on the ear fringes and tail bristles, with the rest distributed rather sparsely over the rest of the body. White rhinos have the distinctive flat broad mouth that is used for grazing.[12]

Black

The name "black rhinoceros" (Diceros bicornis) was chosen to distinguish this species from the white rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum). This can be confusing, as the two species are not truly distinguishable by color. There are four subspecies of black rhino: South-central (Diceros bicornis minor), the most numerous, which once ranged from central Tanzania south through Zambia, Zimbabwe and Mozambique to northern and eastern South Africa; South-western (Diceros bicornis occidentalis) which are better adapted to the arid and semi-arid savannas of Namibia, southern Angola, western Botswana and western South Africa; East African (Diceros bicornis michaeli), primarily in Tanzania; and West African (Diceros bicornis longipes) which was declared extinct in November 2011.[14] The native Tswanan name keitloa describes a South African variation of the black rhino in which the posterior horn is equal to or longer than the anterior horn.[15]

An adult black rhinoceros stands 1.50–1.75 m (59–69 in) high at the shoulder and is 3.5–3.9 m (11–13 ft) in length.[16] An adult weighs from 850 to 1,600 kg (1,870 to 3,530 lb), exceptionally to 1,800 kg (4,000 lb), with the females being smaller than the males. Two horns on the skull are made of keratin with the larger front horn typically 50 cm long, exceptionally up to 140 cm. Sometimes, a third smaller horn may develop.[17] The black rhino is much smaller than the white rhino, and has a pointed mouth, which it uses to grasp leaves and twigs when feeding.

During the latter half of the 20th century, their numbers were severely reduced from an estimated 70,000[18] in the late 1960s to a record low of 2,410 in 1995. Since then, numbers have been steadily increasing at a continental level with numbers doubling to 4,880 by the end of 2010. As of 2008, the numbers are still 90% lower than three generations ago.[19]

Indian

The Indian rhinoceros, or greater one-horned rhinoceros, (Rhinoceros unicornis) has a single horn 20 to 60 cm long.[20] It is nearly as large as the African white rhino. Its thick, silver-brown skin folds into the shoulder, back, and rump, giving it an armored appearance. Its upper legs and shoulders are covered in wart-like bumps, and it has very little body hair. Grown males are larger than females in the wild, weighing from 2,500–3,200 kg (5,500–7,100 lb). Shoulder height is 1.75–2.0 m (5.7–6.6 ft). Females weigh about 1,900 kg (4,200 lb) and are 3–4 m (9.8–13 ft) long. The record-sized specimen was approximately 4,000 kg (8,800 lb).[21]

Indian rhinos once inhabited many areas ranging from Pakistan to Myanmar and maybe even parts of China. Because of humans, they now exist in only several protected areas of India (in Assam, West Bengal, and a few pairs in Uttar Pradesh) and Nepal, plus a pair in Lal Suhanra National Park in Pakistan reintroduced there from Nepal. They are confined to the tall grasslands and forests in the foothills of the Himalayas. Two-thirds of the world's Indian rhinoceroses are now confined to the Kaziranga National Park situated in the Golaghat district of Assam, India.[22]

Javan

The Javan rhinoceros (Rhinoceros sondaicus) is one of the most endangered large mammals in the world.[23] According to 2015 estimates, only about 60 remain, in Java, Indonesia, all in the wild. It is also the least known rhino species. Like the closely related, and larger, Indian rhinoceros, the Javan rhino has a single horn. Its hairless, hazy gray skin falls into folds into the shoulder, back, and rump, giving it an armored appearance. Its length reaches 3.1–3.2 m (10–10 ft) including the head, and its height 1.5–1.7 m (4 ft 11 in – 5 ft 7 in). Adults are variously reported to weigh 900–1,400 kg[24] or 1,360–2,000 kg.[25] Male horns can reach 26 cm in length, while in females they are knobs or altogether absent.[25] These animals prefer dense lowland rain forest, tall grass and reed beds that are plentiful with large floodplains and mud wallows.

Though once widespread throughout Asia, by the 1930s they were nearly hunted to extinction in Nepal, India, Burma, Peninsular Malaysia, and Sumatra for the supposed medical powers of their horns and blood. As of 2015, only 58–61 individuals remain in Ujung Kulon National Park, Java, Indonesia. The last known Javan rhino in Vietnam was reportedly killed for its horn in 2011 by Vietnamese poachers. Now only Java contains the last Javan rhinos.[26][27][28][29]

Sumatran

The Sumatran rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis) is the smallest extant rhinoceros species, as well as the one with the most hair. It can be found at very high altitudes in Borneo and Sumatra. Due to habitat loss and poaching, their numbers have declined and it has become the second most threatened rhinoceros. About 275 Sumatran rhinos are believed to remain. There are three subspecies of Sumatran rhinoceros: the Sumatran rhinoceros proper (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis sumatrensis), the Bornean rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis harrissoni) and the possibly extinct Northern Sumatran rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis lasiotis).

A mature rhino typically stands about 1.3 m (4 ft 3 in) high at the shoulder, has a length of 2.4–3.2 m (7 ft 10 in – 10 ft 6 in) and weighs around 700 kg (1,500 lb), though the largest individuals have been known to weigh as much as 1,000 kilograms (2,200 lb). Like the African species, it has two horns; the larger is the front (25–79 centimetres (9.8–31.1 in)), with the smaller usually less than 10 centimetres (3.9 in) long. Males have much larger horns than the females. Hair can range from dense (the densest hair in young calves) to sparse. The color of these rhinos is reddish brown. The body is short and has stubby legs. The lip is prehensile.

Sumatran rhinoceros are on the verge of extinction due to loss of habitat and illegal hunting. Once they were spread across South-east Asia, but now they are confined to several parts of Indonesia and Malaysia due to reproductive isolation. There were 320 D. sumatrensis in 1995, which by 2011 have dwindled to 216. It has been found through DNA comparison that the Sumatran rhinoceros is the most ancient extant rhinoceros and related to the extinct Eurasian woolly rhino species, Coelodonta. In 1994 Alan Rabinowitz publicly denounced governments, non-governmental organizations, and other institutions for lacking in their attempts to conserve the Sumatran rhinoceros. To conserve it, they would have to relocate them from small forests to breeding programs that could monitor their breeding success. To boost reproduction, the Malaysian and Indonesian governments could also agree to exchange the gametes of the Sumatran and (smaller) Bornean subspecies. The Indonesian and Malaysian governments have also proposed a single management unit for these two ancient subspecies.[30][31]

Plantations for palm oil have taken out the living areas and led to the eradication of the rhino in Sumatra.[32]

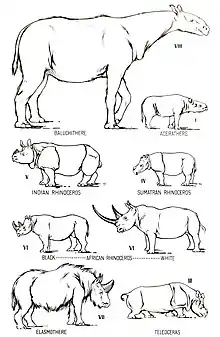

Evolution

Rhinocerotoids diverged from other perissodactyls by the early Eocene. Fossils of Hyrachyus eximus found in North America date to this period. This small hornless ancestor resembled a tapir or small horse more than a rhino. Four families, sometimes grouped together as the superfamily Rhinocerotoidea, evolved in the late Eocene, namely the Hyracodontidae, Amynodontidae, Paraceratheriidae and Rhinocerotidae.

Hyracodontidae

Hyracodontidae, also known as "running rhinos", showed adaptations for speed, and would have looked more like horses than modern rhinos. The smallest hyracodontids were dog-sized. Hyracodontids spread across Eurasia from the mid-Eocene to early Oligocene.

Amynodontidae

The Amynodontidae, also known as "aquatic rhinos", dispersed across North America and Eurasia, from the late Eocene to early Oligocene. The amynodontids were hippopotamus-like in their ecology and appearance, inhabiting rivers and lakes, and sharing many of the same adaptations to aquatic life as hippos.

Paraceratheriidae

The Paraceratheriidae, also known as paraceratheres or indricotheres, originated in the Eocene epoch and lived until the early Miocene. The first paraceratheres were only about the size of large dogs, growing progressively larger in the late Eocene and Oligocene. The largest genus of the family was Paraceratherium, which was more than twice as heavy as a bull African elephant, and was one of the largest land mammals that ever lived.

Rhinocerotidae

The family of all modern rhinoceros, the Rhinocerotidae, first appeared in the Late Eocene in Eurasia. The earliest members of Rhinocerotidae were small and numerous; at least 26 genera lived in Eurasia and North America until a wave of extinctions in the middle Oligocene wiped out most of the smaller species. Several independent lineages survived. Menoceras, a pig-sized rhinoceros, had two horns side by side. The North American Teleoceras had short legs, a barrel chest and lived until about five million years ago. The last rhinos in the Americas became extinct during the Pliocene.

Modern rhinos are thought to have begun dispersal from Asia during the Miocene. Alongside the extant species, four additional species of rhinoceros survived into the Last Glacial Period: the woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis), Elasmotherium sibiricum and two species of Stephanorhinus, Merck's rhinoceros (Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis) and the Narrow-nosed rhinoceros (Stephanorhinus hemitoechus).[34] The woolly rhinoceros appeared in China around 1 million years ago and first arrived in Europe around 600,000 years ago. It reappeared 200,000 years ago, alongside the woolly mammoth, and became numerous. Elasmotherium was two meters tall, five meters long and weighed around five tons, with a single enormous horn, hypsodont teeth and long legs for running. The latest known well dated bones of Elasmotheriumin found in the south of Western Siberia (the area that is today Kazakhstan) date as recently as 39,000 years ago.[35]

The origin of the two living African rhinos can be traced to the late Miocene (6 mya) species Ceratotherium neumayri. The lineages containing the living species diverged by the early Pliocene, when Diceros praecox, the likely ancestor of the black rhinoceros, appears in the fossil record.[36] The black and white rhinoceros remain so closely related that they can still mate and successfully produce offspring.[10]

Cladogram showing the relationships of recent and Late Pleistocene rhinoceros species (minus Stephanorhinus hemitoechus) based on whole nuclear genomes, after Liu et al., 2021:[34]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

† denotes extinct taxa

- Family Rhinocerotidae[37]

- †Teletaceras

- †Uintaceras

- Subfamily Rhinocerotinae

- Tribe Aceratheriini

- †Aceratherium lived from 33.9 to 3.4 Ma

- †Acerorhinus 13.6–7.0 Ma

- †Alicornops[38] 13.7–5.3 Ma

- †Aphelops 20.43–5.33 Ma

- †Chilotheridium[39] 23.0–11.6 Ma

- †Chilotherium 13.7–3.4 Ma

- †Floridaceras 20.4–16.3 Ma

- †Hoploaceratherium[40] 16.9–16.0 Ma

- †Mesaceratherium

- †Peraceras 20.6–10.3 Ma

- †Plesiaceratherium 20.0–11.6 Ma

- †Ronzotherium 37–23 Ma

- †Shansirhinus

- †Sinorhinus[41]

- †Subchilotherium[42]

- Tribe Teleoceratini

- Rhinocerotina Burdigalian–Present

- Tribe Rhinocerotini 40.4–11.1 Ma–Present

- †Gaindatherium[45] 11.6–11.1 Ma

- Subtribe Rhinocerotina 17.5 Ma–Present[46]

- †Nesorhinus .70 Ma

- †Rusingaceros 17.5 Ma

- Rhinoceros – Indian & Javan rhinoceros

- Tribe Dicerorhinini

- †Coelodonta – Woolly rhinoceros

- Dicerorhinus – Sumatran rhinoceros

- †Dihoplus[47] 11.610–1.810 Ma

- †Lartetotherium 15.97–8.7 Ma

- †Stephanorhinus 9.7–0.04 Ma – Merck's rhinoceros & Narrow-nosed rhinoceros

- Tribe Dicerotini 23.0–Present

- Ceratotherium – White rhinoceros 7.25–Present

- Diceros – Black rhinoceros 23.0–Present

- †Paradiceros[48] 15.97–11.61 Ma

- Rhinocerotinae incertae sedis

- †Protaceratherium[49]

- Tribe Rhinocerotini 40.4–11.1 Ma–Present

- Tribe Aceratheriini

- Subfamily Elasmotheriinae

- †Gulfoceras 23.03–20.43 Ma

- †Victoriaceros[50] 15 Ma

- Tribe Diceratheriini

- †Diceratherium 33.9–11.6 Ma

- †Penetrigonias

- †Subhyracodon 38.0–26.3 Ma

- †Trigonias 37-34 Ma

- Tribe Elasmotheriini 20.0–0.1 Ma

- †Bugtirhinus 20.0–16.9 Ma

- †Caementodon

- †Elasmotherium – Giant rhinoceros 3.6–0.039 Ma

- †Hispanotherium synonymized with Huaqingtherium 16.0–7.25 Ma

- †Iranotherium

- †Kenyatherium[39]

- †Meninatherium

- †Menoceras 23.03–16.3 Ma

- †Ningxiatherium[51]

- †Ougandatherium[39] 20.0–16.9 Ma

- †Parelasmotherium[52]

- †Procoelodonta[53]

- †Sinotherium 9.0–5.3 Ma

Predators, poaching and hunting

.png.webp)

Adult rhinoceros have no real predators in the wild, other than humans. Young rhinos sometimes fall prey to big cats, crocodiles, African wild dogs, and hyenas.

Although rhinos are large and aggressive and have a reputation for being resilient, they are very easily poached; they visit water holes daily and can be easily killed while they drink. As of December 2009, poaching increased globally while efforts to protect the rhino are considered increasingly ineffective. The most serious estimate, that only 3% of poachers are successfully countered, is reported of Zimbabwe, while Nepal has largely avoided the crisis.[55] Poachers have become more sophisticated. South African officials have called for urgent action against poaching after poachers killed the last female rhino in the Krugersdorp Game Reserve near Johannesburg.[56] Statistics from South African National Parks show that 333 rhinoceros were killed in South Africa in 2010,[57] increasing to 668 by 2012,[58] over 1,004 in 2013,[59][60][61] and over 1,338 killed in 2015.[62] In some cases rhinos are drugged and their horns removed, while in other instances more than the horn is taken.[63]

The Namibian government has supported the practice of rhino trophy hunting as a way to raise money for conservation. Hunting licenses for five Namibian Black rhinos are auctioned annually, with the money going to the government's Game Products Trust Fund. Some conservationists and members of the public oppose or question this practice.[64]

Horn use

Rhinoceros horns develop from subcutaneous tissues, and are made of keratinous mineralized compartments. The horns root in a germinative layer.[67]

Rhinoceros horns are used in traditional medicines in parts of Asia, and for dagger handles in Yemen and Oman. Esmond Bradley Martin has reported on the trade for dagger handles in Yemen.[68] In Europe, it was historically believed that rhino horns could purify water and could detect poisoned liquids, and likely as an aphrodisiac and an antidote to poison.[69]

It is a common misconception that rhinoceros horn in powdered form is used as an aphrodisiac[70] or a cure for cancer in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) as Cornu Rhinoceri Asiatici (犀角, xījiǎo, "rhinoceros horn"); no TCM text in history has ever mentioned such prescriptions.[71][72][73][74] In TCM, rhino horn is sometimes prescribed for fevers and convulsions,[75] a treatment not supported by evidence-based medicine: this treatment has been compared to consuming fingernail clippings in water.[76] In 1993, China signed the CITES treaty and removed rhinoceros horn from the Chinese medicine pharmacopeia, administered by the Ministry of Health. In 2011, the Register of Chinese Herbal Medicine in the United Kingdom issued a formal statement condemning the use of rhinoceros horn.[77] A growing number of TCM educators are also speaking out against the practice,[78] although some TCM practitioners still believe that it is a life-saving medicine.[79]

Vietnam reportedly has the biggest number of rhino horn consumers, with their demand driving most of the poaching, which has risen to record levels.[80][81][82] The "Vietnam CITES Management Authority" has claimed that Hanoi recently experienced a 77% drop in the usage of rhino horn, but National Geographic has challenged these claims, noticing that there was no rise in the numbers of criminals who were apprehended or prosecuted.[83] South African rhino poaching's main destination market is Vietnam.[84] An average sized horn can bring in as much as a quarter of a million dollars in Vietnam and many rhino range states have stockpiles of rhino horn.[85][86]

Horn trade

International trade in rhinoceros horn has been declared illegal by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) since 1977.[87] A proposal by Swaziland to lift the international ban was rejected in October 2016.[88] Domestic sale of rhinoceros horn in South Africa, home of 80% of the remaining rhino population,[89] was banned as of 2009. The ban was overturned in a court case in 2017, and South Africa plans to draft regulations for the sale of rhino horn, possibly including export for "non-commercial purposes".[90] The South African government has proposed that a legal trade of rhino horn be established, arguing that this could reduce poaching and prevent the extinction of this species.[91]

In March 2013, some researchers suggested that the only way to reduce poaching would be to establish a regulated trade based on humane and renewable harvesting from live rhinos.[92] The World Wildlife Fund opposes legalization of the horn trade, as it may increase demand,[93] while IFAW released a report by EcoLarge, suggesting that more thorough knowledge of economic factors is required to justify the pro-trade option.[94]

Conservation

According to the World Wide Fund for Nature, conservation of African rhinoceroses as consumers of large amounts of vegetation is crucial to maintaining the shape of the African landscape and the natural resources of local communities.[95]

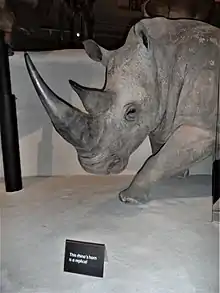

Horn removal

To prevent poaching, in certain areas, rhinos have been tranquillized and their horns removed. Armed park rangers, particularly in South Africa, are also working on the front lines to combat poaching, sometimes killing poachers who are caught in the act. A 2012 spike in rhino killings increased concerns about the future of the species.[96][97][98][99]

Horn poisoning

In 2011, the Rhino Rescue Project began a horn-trade control method consisting of infusing the horns of living rhinos with a mixture of a pink dye and an acaricide (to kill ticks) which is safe for rhinos but toxic to humans.[100][101] The procedure also includes inserting three RFID identification chips and taking DNA samples.[100] Because of the fibrous nature of rhino horn, the pressurized dye infuses the interior of the horn but does not color the surface or affect rhino behavior. Depending on the quantity of horn a person consumes, experts believe the acaricide would cause nausea, stomach-ache, and diarrhea, and possibly convulsions. It would not be fatal—the primary deterrent is the knowledge that the treatment has been applied, communicated by signs posted at the refuges. The original idea grew out of research into the horn as a reservoir for one-time tick treatments, and experts selected an acaricide they think is safe for the rhino, oxpeckers, vultures, and other animals in the preserve's ecosystem.[100] Proponents claim that the dye cannot be removed from the horns, and remains visible on x-ray scanners even when the horn is ground to a fine powder.[100][102]

The UK charity organization Save the Rhino has criticized horn poisoning on moral and practical grounds. The organization questions the assumptions that the infusion technique works as intended, and that even if the poison were effective, whether middlemen in a lucrative, illegal trade would care much about the effect it would have on buyers.[103] Additionally, rhino horn is increasingly purchased for decorative use, rather than for use in traditional medicine. Save the Rhino questions the feasibility of applying the technique to all African rhinos, since workers would have to reapply the acaricide every 4 years.[103] It was also reported that one out of 150 rhinos treated did not survive the anesthesia.[101]

Artificial substitute for rhinoceros horn

Another way to undercut the rhinoceros horn market has been suggested by Matthew Markus of Pembient, a biotechnology firm. He proposes the synthesis of an artificial substitute for rhinoceros horn. To enable authorities to distinguish the bioengineered horn from real rhinoceros horn, the genetic code of the bioengineered horn could be registered, similar to the DNA of living rhinoceros in the RhODIS (Rhino DNA Index System). Initial responses from many conservationists were negative, but a 2016 report from TRAFFIC—which monitors trade in wildlife and animal parts—conceded that it "...would be rash to rule out the possibility that trade in synthetic rhinoceros horn could play a role in future conservation strategies".[104]

Historical representations

Greek historian and geographer Agatharchides (2nd century BC) mentions the rhinoceros in his book On the Erythraean Sea.

Albrecht Dürer created a famous woodcut of a rhinoceros in 1515, based on a written description and brief sketch by an unknown artist of an Indian rhinoceros that had arrived in Lisbon earlier that year. He never saw the animal itself, so Dürer's Rhinoceros is a somewhat inaccurate depiction.[105] Rhinoceros are depicted in the Chauvet Cave in France, pictures dated to 10,000–30,000 years ago.

There are legends about rhinoceroses stamping out fire in Burma, India, and Malaysia. The mythical rhinoceros has a special name in Malay, badak api, wherein badak means rhinoceros, and api means fire. The animal would come when a fire was lit in the forest and stamp it out.[106] There are no recent confirmations of this phenomenon. This legend was depicted in the film The Gods Must Be Crazy (1980), which shows an African rhinoceros putting out two campfires.[107]

In 1974 a lavender rhinoceros symbol began to be used as a symbol of the gay community in Boston.[108]

See also

Conservation

- Bardiya National Park

- Chitwan National Park

- International Rhino Foundation

- Kaziranga National Park

- List of odd-toed ungulates by population

- Nicolaas Jan van Strien

- Save the Rhino

- TRAFFIC

Individual rhinoceroses

- Abada

- Clara

- List of fictional pachyderms

- Rhinoceros of Versailles

Literature

- Rhinoceros, 1959 play

Other

- Rhinoceroses in ancient China

References

- "Glossary. American Museum of Natural History". Archived from the original on 20 November 2021.

- Owen-Smith, Norman (1984). Macdonald, D. (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Mammals. New York: Facts on File. pp. 490–495. ISBN 978-0-87196-871-5.

- "Vietnam's Appetite For Rhino Horn Drives Poaching In Africa". NPR. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- "What is a rhinoceros horn made of?". Yesmag.bc.ca. 9 October 2003. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Cheung, Hubert; Mazerolle, Lorraine; Possingham, Hugh; Biggs, Duan (1 February 2021). "Rhino horn use by consumers of traditional Chinese medicine in China". Conservation Science and Practice. 3 (5). doi:10.1111/csp2.365.

- Vigne, Lucy; Martin, Esmond (January–March 2018). "Amid conflict, Yemen's demand for rhino horn daggers continues" (PDF). Swara – via Rhino Resource Center.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Tougard, C. et al. (2001) Phylogenetic relationships of the five extant Rhinoceros species (Rhinocerotidae, Perissodactyla) based on mitochondrial cytochrome b and 12S rRNA genes.

- Merriam-Webster Dictionary

- Rabinowitz, Alan (1995). "Helping a Species Go Extinct: The<33 six. Sumatran Rhino in Borneo" (PDF). Conservation Biology. 9 (3): 482–488. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1995.09030482.x.

- Robinson, Terry J.; V. Trifonov; I. Espie; E.H. Harley (January 2005). "Interspecific hybridization in rhinoceroses: Confirmation of a Black × White rhinoceros hybrid by karyotype, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and microsatellite analysis". Conservation Genetics. 6 (1): 141–145. doi:10.1007/s10592-004-7750-9. S2CID 33993269.

- Houck, ML; Ryder, OA; Váhala, J; Kock, RA; Oosterhuis, JE (January–February 1994). "Diploid chromosome number and chromosomal variation in the white rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum)". The Journal of Heredity. 85 (1): 30–34. PMID 8120356.

- Skinner, John D.; Chimimba, Christian T. (2005). The Mammals of the Southern African Subregion. Cambridge University Press. p. 527. ISBN 978-0-521-84418-5.

- Rookmaaker, Kees (2003). "Why the name of the white rhinoceros is not appropriate". Pachyderm. 34: 88–93.

- "Western black rhino declared extinct". BBC. 9 November 2011. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- Keitloa | Define Keitloa at Dictionary.com. Dictionary.reference.com. Retrieved on 21 February 2012.

- Dollinger, Peter; Silvia Geser. "Black Rhinoceros". World Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Archived from the original on 16 July 2009. Retrieved 9 October 2007.

- "About the Black Rhino". Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- "WWF Factsheet; Black Rhinoceros Diceros Bicornis" (PDF). World Wildlife Fund. October 2004. Retrieved 9 October 2007.

- Emslie, R. (2020). "Diceros bicornis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T6557A152728945. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-1.RLTS.T6557A152728945.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- Prasanta Mazumdar (30 August 2016). "One of world's biggest rhino horns found in Assam". The New Indian Express. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- Panda, Sasmita; Panigrahi, Gagan Kumar; Padhi, Surendra nath (16 February 2016). Wild Animals of India. Anchor Academic Publishing. ISBN 9783960675143.

- Bhaumik, Subir (17 April 2007). "Assam rhino poaching 'spirals'". BBC News. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- Derr, Mark (11 July 2006). "Racing to Know the Rarest of Rhinos, Before It's Too Late". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 October 2007.

- Species extinct: Javan Rhinoceros Archived 6 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Rhino Guide: Javan Rhinoceros

- "Group: Last Javan rhino in Vietnam killed for horn". USA Today.

- "Last rare rhinoceros in Vietnam killed by poacher, group says". CNN.

- Kinver, Mark (25 October 2011). "Javan rhino 'now extinct in Vietnam'". BBC News. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- "Javan Rhino". WWF. 2015. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- Ahmad Zafir, Abdul Wahab; Payne, Junaidi; Mohamed, Azlan; Lau, Ching Fong; Sharma, Dionysius Shankar Kumar; Alfred, Raymond; Williams, Amirtharaj Christy; Nathan, Senthival; Ramono, Widodo S.; Clements, Gopalasamy Reuben (2011). "Now or never: what will it take to save the Sumatran rhinoceros Dicerorhinus sumatrensis from extinction?". Oryx. 45 (2): 225–233. doi:10.1017/S0030605310000864. ISSN 0030-6053.

- Benoît, Goossens; Milena Salgado-Lynn; Jeffrine J. Rovie-Ryan; Abdul H. Ahmad; Junaidi Payne; Zainal Z. Zainuddin; Senthilvel K. S. S. Nathan; Laurentius N. Ambu (2013). "Genetics and the last stand of the Sumatran rhinoceros Dicerorhinus sumatrensis". Oryx. 47 (3): 340–344. doi:10.1017/S0030605313000045.

- Beachy, Ben (7 December 2015). "Sharks, Tigers, and Elephants: New Analysis Reveals TPP Threats to Endangered Species". Sierra Club.

- Hieronymus, Tobin L. (March 2009). "Osteological Correlates of Cephalic Skin Structures in Amniota: Documenting the Evolution of Display and Feeding Structures with Fossil Data" (PDF). p. 3.

- Liu, Shanlin; Westbury, Michael V.; Dussex, Nicolas; Mitchell, Kieren J.; Sinding, Mikkel-Holger S.; Heintzman, Peter D.; Duchêne, David A.; Kapp, Joshua D.; von Seth, Johanna; Heiniger, Holly; Sánchez-Barreiro, Fátima (24 August 2021). "Ancient and modern genomes unravel the evolutionary history of the rhinoceros family". Cell. 184 (19): 4874–4885.e16. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2021.07.032. ISSN 0092-8674. PMID 34433011.

- Kosintsev, Pavel; Mitchell, Kieren J.; Devièse, Thibaut; van der Plicht, Johannes; Kuitems, Margot; Petrova, Ekaterina; Tikhonov, Alexei; Higham, Thomas; Comeskey, Daniel; Turney, Chris; Cooper, Alan (26 November 2018). "Evolution and extinction of the giant rhinoceros Elasmotherium sibiricum sheds light on late Quaternary megafaunal extinctions". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 3 (1): 31–38. doi:10.1038/s41559-018-0722-0. hdl:11370/78889dd1-9d08-40f1-99a4-0e93c72fccf3. ISSN 2397-334X. PMID 30478308. S2CID 53726338.

- Geraads, Denis (2005). "Pliocene Rhinocerotidae (Mammalia) from Hadar and Dikika (Lower Awash, Ethiopia), and a revision of the origin of modern African rhinos". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 25 (2): 451–460. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0451:PRMFHA]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 52105151. Archived from the original on 23 May 2008.

- Haraamo, Mikko (15 November 2005). "Mikko's Phylogeny Archive entry on "Rhinoceratidae"". Archived from the original on 27 November 2005. Retrieved 7 January 2008.

- Deng, T. (November 2004). "A new species of the rhinoceros Alicornops from the Middle Miocene of the Linxia Basin, Gansu, China". Palaeontology. 47 (6): 1427–1439. doi:10.1111/j.0031-0239.2004.00420.x. S2CID 128614366.

- Handa, N.; Nakatsukasa, M.; et al. (2015). "New specimens of Chilotheridium (Perissodactyla, Rhinocerotidae) from the Upper Miocene Namurungule and Nakali Formations, Northern Kenya". Paleontological Research. 19 (3): 181–194. doi:10.2517/2014PR035. S2CID 130817602.

- Giaourtsakis, I.X. (2003). "Late Neogene Rhinocerotidae of Greece: distribution, diversity and stratigraphical range". Deinsea. 10 (1): 235–254. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- Barasoain, D.; Azanza, B. (September 2017). "Geoheritage and education: a practical example from the rhinoceros of Toril 3 (Calatayud-Daroca Basin, Spain)". Geoheritage. 10 (3): 364–374. doi:10.1007/s12371-017-0258-8. S2CID 164492857.

- Lu, X.; Ji, X.; et al. (2019). "Palaeoenvironment examination of the terminal Miocene hominoid locality of the Zhaotong Basin, southwestern China, based on the rhinocerotid remains". Historical Biology. 31 (2): 234–242. doi:10.1080/08912963.2017.1360294. S2CID 133755235.

- Deng, T. (2013). "Incisor fossils of Aprotodon(Perissodactyla, Rhinocerotidae) from the Early Miocene Shangzhuang Formation of the Linxia Basin in Gansu, China" (PDF). Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 51: 131–140. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- Mörs, T. (April 2016). "Biostratigraphy and paleoecology of continental Tertiary vertebrate faunas in the Lower Rhine Embayment (NW-Germany)". Netherlands Journal of Geosciences. 81 (Sp2): 1771–1783. doi:10.1017/S0016774600022411.

- Khan, A.M.; Cerdeno, E.; et al. (June 2014). "New fossils of Gaindatherium (Rhinocerotidae, Mammalia) from the Middle Miocene of Pakistan". Turkish Journal of Earth Sciences. 23: 452–461. doi:10.3906/yer-1312-24.

- Geraads, Denis (2010). "Chapter 34: Rhinocerotidae". In Werdelin, L.; Sanders, W.J. (eds.). Cenozoic Mammals of Africa. University of California Press. pp. 675–689. ISBN 978-0-520-25721-4.

- Pandolfi, L.; Rivals, F.; Rabinovich, R. (January 2020). "A new species of rhinoceros from the site of Bethlehem: ‘Dihoplus’ bethlehemsis sp. nov. (Mammalia, Rhinocerotidae)". Quaternary International. 537: 48–60. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2020.01.011. S2CID 213080180.

- Pandolfi, L. (2018). "Evolutionary history of Rhinocerotina (Mammalia, Perissodactyla)". Fossilia. 2018: 26–32. doi:10.32774/FosRepPal.20.1810.102732. ISBN 9791220034081.

- Becker, Damien; Pierre-Olivier, Antoine; Maridet, Olivier (22 March 2013). "A new genus of Rhinocerotidae (Mammalia, Perissodactyla) from the Oligocene of Europe" (PDF). Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 11 (8): 947–972. doi:10.1080/14772019.2012.699007. S2CID 55036210.

- Geraads, Denis; McCrossin, Monte; Benefit, Brenda (2012). "A New Rhinoceros, Victoriaceros kenyensis gen. et sp. nov., and Other Perissodactyla from the Middle Miocene of Maboko, Kenya". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 19: 57–75. doi:10.1007/s10914-011-9183-9. S2CID 1547306.

- Deng, Tao (2008). "A new elasmothere (Perissodactyla, Rhinocerotidae) from the late Miocene of the Linxia Basin in Gansu, China" (PDF). Geobios. 41 (6): 719–728. doi:10.1016/j.geobios.2008.01.006.

- Deng, T. (2007). "Skull of Parelasmotherium (Perissodactyla, Rhinocerotidae) from the Upper Miocene in the Linxia Basin (Gansu, China)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27 (2): 467–475. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[467:SOPPRF]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 130213090.

- Antoine, P. (February 2003). "Middle Miocene elasmotheriine Rhinocerotidae from China and Mongolia: taxonomic revision and phylogenetic relationships". Zoologica Scripta. 32 (2): 95–118. doi:10.1046/j.1463-6409.2003.00106.x. S2CID 86800130.

- Data compiled by the International Rhino Foundation

- "'Global surge' in rhino poaching". BBC. 1 December 2009. Retrieved 9 May 2016.

- "Poachers kill last female rhino in South African park for prized horn". The Guardian. 18 July 2010. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- "Rhino poachers bring death toll in South Africa to record high". The Guardian. 4 November 2011. Retrieved 9 May 2016.

- "Update on rhino poaching statistics". South African National Parks. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- Lucero, Louis II (17 January 2014). "South Africa: Rhino Killings Increase". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- "Rhino poaching update" (Press release). Department of Environmental Affairs. 19 December 2013. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

- "946 rhino killed in 2013". Eyewitness News. 19 December 2013. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

- "Record number of African rhinos killed in 2015". The Guardian. 9 March 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- Mngoma, Nosipho (19 December 2013). "R100 000 reward for rhino poachers". IOL. Independent Newspapers. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- Welz, Adam (14 January 2014). "Kill a Rhino to save its species?". Deutsche Welle (DW). Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- "Weight of seized rhino horns". Our World in Data. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- "Rhino heads, horns worth €500,000 stolen in Dublin". The Irish Times.

- Nasoori, A (2020). "Formation, structure, and function of extra-skeletal bones in mammals". Biological Reviews. 95 (4): 986–1019. doi:10.1111/brv.12597. PMID 32338826. S2CID 216556342 – via Wiley.

- "GCC: Esmond Bradly Martin Reports From Yemen". Gcci.org. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- "Facts about Rhino Horn" (PDF). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

- Hsu, Jeremy (5 April 2017). "The Hard Truth about the Rhino Horn "Aphrodisiac" Market". Scientific American. Archived from the original on March 2021.

- Guilford, Gwynn (15 May 2013). "Why Does a Rhino Horn Cost $300,000? Because Vietnam Thinks It Cures Cancer and Hangovers". The Atlantic.

- "Rhino Poaching". Save the Rhino.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Rhino Horn Use: Fact vs. Fiction". PBS. 20 August 2010.

- Richard Ellis (2 November 2012). "Poaching for Traditional Chinese Medicine". Save the Rhino. Archived from the original on 2 November 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Bensky, Dan; Clavey, Steven; Stoger, Erich and Gamble, Andrew (2004) Chinese Herbal Medicine: Materia Medica, 3rd Edition. Eastland Press. ISBN 0-939616-42-4

- "Bitter Pills – Parts from some endangered species are worth more than gold or cocaine", The Economist, 18 July 2014.

- Larson, Rhishja (9 September 2011). "Chinese Medicine Organization Speaks Out Against Use of Rhino Horn". RhinoConservation.org. Archived from the original on 25 September 2011. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- Larson, Rhishja (15 August 2011). "TCM Educators Speak Out Against Use of Rhino Horn". RhinoConservation.org. Archived from the original on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- Parry-Jones, Rob; Amanda Vincent (3 January 1998). "Can we tame wild medicine? To save a rare species, Western conservationists may have to make their peace with traditional Chinese medicine". New Scientist. Vol. 157, no. 2115. Archived from the original on 22 June 2006.

- Milliken, Tom; Shaw, Jo (2012). The South Africa – Viet Nam Rhino Horn Trade Nexus (PDF). Johannesburg, South Africa: TRAFFIC. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-9584025-8-3.

- Wener-Fligner, Zach (13 July 2014). "Rich Vietnamese snorting rhino horns are causing a poaching explosion in South Africa". Quartz.

- Roberts, Sue Lloyds (9 February 2014). "Vietnam's illegal trade in rhino horn". BBC.

- Society, Wildlife Conservation (3 November 2014). "Has Demand for Rhino Horn Truly Dropped in Vietnam?". nationalgeographic.com.

- Northam, Jackie (28 January 2015). "Tiger Skins And Rhino Horns: Can A Trade Deal Halt The Trafficking?". NPR."Rhino poaching on the rise, ministers pledge to tackle illegal horn trade". International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development. 19 February 2015.

- Frank, Meghan; Hopper, Jessica (21 February 2012). "Spike in rhino poaching threatens survival of species". Archived from the original on 22 February 2012.

- Milledge, Simon (2005). "Rhino Horn Stockpile" (PDF). (1.34 MB), TRAFFIC. Retrieved 9 January 2008.

- Baker, Aryn (29 January 2016). "Legalizing the Sale of Rhino Horn May Only Endanger the Animals More". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- Actman, Jani (3 October 2016). "The World Votes to Keep Rhino Horn Sales Illegal: A proposal by Swaziland to legalize trade in rhino horn was rejected at the wildlife trade conference in South Africa". National Geographic. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- Bale, Rachael (22 September 2015). "A Brief History of the Long Fight to End Rhino Slaughter". National Geographic. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- Torchia, Christopher (24 July 2017). "South Africa moves ahead on domestic trade in rhino horn". ABC. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- "Minister Edna Molewa briefs the media on Cabinet approval of the rhino trade proposal for consideration at CITES CoP17 in 2016". Department of Environmental Affairs (Government of South Africa). 3 July 2013. Retrieved 9 May 2016.

- Biggs, D.; Courchamp, F.; Martin, R.; Possingham, H. P. (1 March 2013). "Legal Trade of Africa's Rhino Horns" (PDF). Science. 339 (6123): 1038–1039. Bibcode:2013Sci...339.1038B. doi:10.1126/science.1229998. PMID 23449582. S2CID 206545172. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 January 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- Braun, Maja; et al. (15 March 2013). "Should the rhino horn trade be legalized?". Animals. Deutsche Welle (DW). Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- Michler, Ian (16 January 2014). "Horn of contention: pro-trade thinking comes in for criticism". South Africa. Daily Maverick. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- "African rhinos". wwf.panda.org. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- "Media Release: Latest on Rhino Poaching in South Africa". South African National Parks. 14 February 2012. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- Cutting off horns to save rhinos from poachers

- Cutting off horns to save rhinos from poachers

- Dehorning rhinos

- "About the Rhino Rescue Project". Archived from the original on 6 April 2014.

- Martin Angler (9 May 2013). "Dye and Poison Stop Rhino Poachers".

- "Injecting Poison into Rhinos' Horns To Fight Poaching". George Stroumboulopoulos, Canadian Broadcasting Company. 5 April 2013.

- "Poisoning rhino horns". Save the Rhino International. 2013. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- Roberts, Jacob (2017). "Can Biotech save the rhino?". Distillations. 2 (4): 24–35. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- "The Refusal of Time". Harvard Magazine. 1 May 2012. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- "Rhinoceros Frequently Asked Questions". Sosrhino.org. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- The Gods Must Be Crazy, James Uys, C.A.T. Films, 1980.

- /00:00Playing Live (3 June 2019). "How A Lavender Rhino Became A Symbol Of Gay Resistance In '70s Boston | The ARTery". Wbur.org. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

Further reading

- White Rhinoceros, White Rhinoceros Profile, Facts, Information, Photos, Pictures, Sounds, Habitats, Reports, News – National Geographic

- Laufer, Berthold. 1914. "History of the Rhinoceros". In: Chinese Clay Figures, Part I: Prolegomena on the History of Defence Armour. Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, pp. 73–173.

- Cerdeño, Esperanza (1995). "Cladistic Analysis of the Family Rhinocerotidae (Perissodactyla)" (PDF). Novitates (3143). ISSN 0003-0082. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2009. Retrieved 24 October 2007.

- Foose, Thomas J.; van Strien, Nico (1997). Asian Rhinos – Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland, and Cambridge, UK. ISBN 978-2-8317-0336-7.

- Chapman, January (1999). The Art of Rhinoceros Horn Carving in China. Christies Books, London. ISBN 0-903432-57-9.

- Emslie, R.; Brooks, M. (1999). African Rhino. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. IUCN/SSC African Rhino Specialist Group. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK. ISBN 978-2-8317-0502-6.

- Hieronymus, Tobin L.; Lawrence M. Witmer; Ryan C. Ridgely (2006). "Structure of White Rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum) Horn Investigated by X-ray Computed Tomography and Histology With Implications for Growth and External Form" (PDF). Journal of Morphology. 267 (10): 1172–1176. doi:10.1002/jmor.10465. PMID 16823809. S2CID 15699528.

- "White Rhino (Ceratotherum simum)". Rhinos. The International Rhino Foundation. Archived from the original on 20 July 2009. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- Theresa Seiger (25 December 2019). "Rare black rhino born Christmas Eve at Michigan zoo". Fox23 News.

External links

- Rhino Species & Rhino Images page on the Rhino Resource Center

- Rhinoceros entry on World Wide Fund for Nature website.

- International Anti Poaching Foundation

- Free To Use Rhino Images

- Rhinoceros Resources & Photos on African Wildlife Foundation website

- UK Times article: "South African spy chief linked to rhino horn trade" South African spy chief linked to rhino horn trade

- Video on South African government minister's alleged involvement in illegal rhino horn trade. VIDEO: Rhino poacher says Mahlobo is his 'mate'

- People Not Poaching: The Communities and IWT Learning Platform