North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere.[lower-alpha 2] It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Caribbean Sea, and to the west and south by the Pacific Ocean. Because it is on the North American Tectonic Plate, Greenland is included as a part of North America geographically.

| |

| Area | 24,709,000 km2 (9,540,000 sq mi) (3rd) |

|---|---|

| Population | 592,296,233 (2021; 4th) |

| Population density | 25.7/km2 (66.4/sq mi) (2021)[lower-alpha 1] |

| GDP (PPP) | $30.61 trillion (2022 est.; 2nd)[1] |

| GDP (nominal) | $29.01 trillion (2022 est.; 2nd)[2] |

| GDP per capita | $57,410 (2022 est.; 2nd)[3] |

| Religions | |

| Demonym | North American |

| Countries | 23 sovereign states |

| Dependencies | 23 non-sovereign territories |

| Languages | English, Spanish, French, Dutch, Danish, indigenous languages, and many others |

| Time zones | UTC−10:00 to UTC±00:00 |

| Largest cities | List of urban areas:[5] |

| UN M49 code | 003 – North America019 – Americas001 – World |

.jpg.webp)

North America covers an area of about 24,709,000 square kilometres (9,540,000 square miles), about 16.5% of Earth's land area and about 4.8% of its total surface. North America is the third-largest continent by area, following Asia and Africa, and the fourth by population after Asia, Africa, and Europe. In 2013, its population was estimated at nearly 579 million people in 23 independent states, or about 7.5% of the world's population. In human geography and in the English-speaking world outside the United States, particularly in Canada, "North America" and "North American" can refer to just Canada and the United States together.[6][7][8][9][10]

North America was reached by its first human populations during the Last Glacial Period, via crossing the Bering land bridge approximately 20,000 to 17,000 years ago. The so-called Paleo-Indian period is taken to have lasted until about 10,000 years ago (the beginning of the Archaic or Meso-Indian period). The classic stage spans roughly the 6th to 13th centuries. The first recorded Europeans to visit North America (other than Greenland) were the Norse around 1000 AD. Christopher Columbus's arrival in 1492 sparked a transatlantic exchange which included migrations of European settlers during the Age of Discovery and the early modern period. Present-day cultural and ethnic patterns reflect interactions between European colonists, indigenous peoples, African slaves, immigrants from Europe, Asia, and the descendants of these groups.

Owing to Europe's colonization of the Americas, most North Americans speak European languages such as English, Spanish or French, and their cultures commonly reflect Western traditions. However, in parts of Canada, the United States, Mexico, and Central America, there are indigenous populations continuing their cultural traditions and speaking native languages.

Name

.jpg.webp)

The Americas are usually accepted as having been named after the Italian explorer Amerigo Vespucci by the German cartographers Martin Waldseemüller and Matthias Ringmann.[11] Vespucci, who explored South America between 1497 and 1502, was the first European to suggest that the Americas were not the East Indies, but a different landmass previously unknown by Europeans. In 1507, Waldseemüller produced a world map, in which he placed the word "America" on the continent of South America, in the middle of what is today Brazil. He explained the rationale for the name in the accompanying book Cosmographiae Introductio: "ab Americo inventore ... quasi Americi terram sive Americam (from Americus the discoverer ... as if it were the land of Americus, thus America)".[12] What was known about North American continent was referred to as Parias above what is today Mexico.[13] A 1553 world map published by Petrus Apianus in his Charta Cosmographica, Cum Ventorum Propria Natura et Operatione,[14] North America was called Baccalearum, meaning "realm of the Cod fish", in reference to the abundance of Cod fish on the east coast.[15]

For Waldseemüller, no one should object to the naming of the land after its discoverer. He used the Latinized version of Vespucci's name (Americus Vespucius), but in its feminine form "America", following the examples of "Europa", "Asia" and "Africa". Later, other mapmakers extended the name America to the northern continent, dropping the usage of "Parias". In 1538, Gerard Mercator used America on his map of the world for all the Western Hemisphere.[16]

Some argue that because the convention is to use the surname for naming discoveries (except in the case of royalty), the derivation from "Amerigo Vespucci" could be put in question.[17] In 1874, Thomas Belt published the indigenous name of the Amerrisque Mountains of Central America;[18] the next year, Jules Marcou suggested that the name of the continent stemmed from that of the mountain range.[19] Marcou corresponded with Augustus Le Plongeon, who wrote: "The name AMERICA or AMERRIQUE in the Mayan language means, a country of perpetually strong wind, or the Land of the Wind, and ... the [suffixes] can mean ... a spirit that breathes, life itself."[16]

Mercator on his map called North America "America or New India" (America sive India Nova).[20] The Spanish Empire called its territories in North and South America "Las Indias"; the state body overseeing them was the Council of the Indies.

Extent

The United Nations formally recognizes "North America" as comprising three areas: Northern America, Central America, and the Caribbean. This has been formally defined by the UN Statistics Division.[21][22][23]

"Northern America", as a term distinct from "North America", excludes Central America, which itself may or may not include Mexico (see Central America § Different definitions). In the limited context of the North American Free Trade Agreement, the term covers Canada, the United States, and Mexico, which are the three signatories of that treaty.

France, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Romania, Greece, and the countries of Latin America use a six-continent model, with the Americas viewed as a single continent and North America designating a subcontinent comprising Canada, the United States, Mexico, and Saint Pierre et Miquelon (politically part of France), and often Greenland, and Bermuda.[24][25][26][27][28]

North America has been historically referred to by other names. Spanish North America (New Spain) was often referred to as Northern America, and this was the first official name given to Mexico.[29]

Regions

Geographically, the North American continent has many regions and subregions. These include cultural, economic, and geographic regions. Economic regions included those formed by trade blocs, such as the North American Trade Agreement bloc and Central American Trade Agreement. Linguistically and culturally, the continent could be divided into Anglo-America and Latin America. Anglo-America includes most of Northern America, Belize, and Caribbean islands with English-speaking populations (though sub-national entities, such as Louisiana and Quebec, have large Francophone populations; in Quebec, French is the sole official language[30]).

The southern part of the North American continent is composed of two regions. These are Central America and the Caribbean.[31][32] The north of the continent maintains recognized regions as well. In contrast to the common definition of "North America", which encompasses the whole continent, the term "North America" is sometimes used to refer only to Mexico, Canada, the United States, and Greenland.[33][34][35][36][37]

The term Northern America refers to the northernmost countries and territories of North America: the United States, Bermuda, St. Pierre and Miquelon, Canada, and Greenland.[38][39] Although the term does not refer to a unified region,[40] Middle America—not to be confused with the Midwestern United States—groups the regions of Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean.[41]

North America's largest countries by land area, Canada and the United States, also have well-defined and recognized regions. In the case of Canada, these are (from east to west) Atlantic Canada, Central Canada, Canadian Prairies, the British Columbia Coast, and Northern Canada. These regions also contain many subregions. In the case of the United States—and in accordance with the US Census Bureau definitions—these regions are: New England, Mid-Atlantic, South Atlantic states, East North Central states, West North Central states, East South Central states, West South Central states, Mountain states, and Pacific states. Regions shared between both nations include the Great Lakes region. Megalopolises have formed between both nations in the case of the Pacific Northwest and the Great Lakes Megaregion.

Countries, dependencies, and other territories

| Arms | Flag | Country / Territory[42][43][44] | Area[45] | Population (2021)[46][47] |

Population density |

Capital | Name(s) in official language(s) | ISO 3166-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anguilla (United Kingdom) |

91 km2 (35 sq mi) |

15,753 | 164.8/km2 (427/sq mi) |

The Valley | Anguilla | AIA | ||

| Antigua and Barbuda | 442 km2 (171 sq mi) |

93,219 | 199.1/km2 (516/sq mi) |

St. John's | Antigua and Barbuda | ATG | ||

| Aruba (Kingdom of the Netherlands)[lower-alpha 3] |

180 km2 (69 sq mi) |

106,537 | 594.4/km2 (1,539/sq mi) |

Oranjestad | Aruba | ABW | ||

| The Bahamas[lower-alpha 4] | 13,943 km2 (5,383 sq mi) |

407,906 | 24.5/km2 (63/sq mi) |

Nassau | Bahamas | BHS | ||

| Barbados | 430 km2 (170 sq mi) |

281,200 | 595.3/km2 (1,542/sq mi) |

Bridgetown | Barbados | BRB | ||

| Belize | 22,966 km2 (8,867 sq mi) |

400,031 | 13.4/km2 (35/sq mi) |

Belmopan | Belize | BLZ | ||

| Bermuda (United Kingdom) |

54 km2 (21 sq mi) |

64,185 | 1,203.7/km2 (3,118/sq mi) |

Hamilton | Bermuda | BMU | ||

| Bonaire (Kingdom of the Netherlands)[lower-alpha 3][48] |

294 km2 (114 sq mi) |

12,093 | 41.1/km2 (106/sq mi) |

Kralendijk | Boneiru | BES | ||

| British Virgin Islands (United Kingdom) |

151 km2 (58 sq mi) |

31,122 | 152.3/km2 (394/sq mi) |

Road Town | British Virgin Islands | VGB | ||

| Canada | 9,984,670 km2 (3,855,100 sq mi) |

38,155,012 | 3.7/km2 (9.6/sq mi) |

Ottawa | Canada | CAN | ||

| Cayman Islands (United Kingdom) |

264 km2 (102 sq mi) |

68,136 | 212.1/km2 (549/sq mi) |

George Town | Cayman Islands | CYM | ||

| Clipperton Island (France) | 6 km2 (2.3 sq mi) |

0 | 0/km2 (0/sq mi) |

— | Île de Clipperton | CPT | ||

| Costa Rica | 51,100 km2 (19,700 sq mi) |

5,153,957 | 89.6/km2 (232/sq mi) |

San José | Costa Rica | CRI | ||

| Cuba | 109,886 km2 (42,427 sq mi) |

11,256,372 | 102.0/km2 (264/sq mi) |

Havana | Cuba | CUB | ||

| Curaçao (Kingdom of the Netherlands)[lower-alpha 3] |

444 km2 (171 sq mi) |

190,338 | 317.1/km2 (821/sq mi) |

Willemstad | Kòrsou | CUW | ||

| Dominica | 751 km2 (290 sq mi) |

72,412 | 89.2/km2 (231/sq mi) |

Roseau | Dominica | DMA | ||

| Dominican Republic | 48,671 km2 (18,792 sq mi) |

11,117,873 | 207.3/km2 (537/sq mi) |

Santo Domingo | República Dominicana | DOM | ||

| El Salvador | 21,041 km2 (8,124 sq mi) |

6,314,167 | 293.0/km2 (759/sq mi) |

San Salvador | El Salvador | SLV | ||

| Federal Dependencies of Venezuela (Venezuela) |

342 km2 (132 sq mi) |

2,155 | 6.3/km2 (16/sq mi) |

Gran Roque | Dependencias Federales de Venezuela | VEN-W | ||

| Greenland (Kingdom of Denmark) |

2,166,086 km2 (836,330 sq mi) |

56,243 | 0.026/km2 (0.067/sq mi) |

Nuuk | Kalaallit Nunaat/Grønland | GRL | ||

| Grenada | 344 km2 (133 sq mi) |

124,610 | 302.3/km2 (783/sq mi) |

St. George's | Gwinàd | GRD | ||

| Guadeloupe (France) |

1,628 km2 (629 sq mi) |

396,051 | 246.7/km2 (639/sq mi) |

Basse-Terre | Gwadloup | GLP | ||

| Guatemala | 108,889 km2 (42,042 sq mi) |

17,608,483 | 128.8/km2 (334/sq mi) |

Guatemala City | Guatemala | GTM | ||

| Haiti | 27,750 km2 (10,710 sq mi) |

11,447,569 | 361.5/km2 (936/sq mi) |

Port-au-Prince | Ayiti/Haïti | HTI | ||

| Honduras | 112,492 km2 (43,433 sq mi) |

10,278,345 | 66.4/km2 (172/sq mi) |

Tegucigalpa | Honduras | HND | ||

| Jamaica | 10,991 km2 (4,244 sq mi) |

2,827,695 | 247.4/km2 (641/sq mi) |

Kingston | Jumieka | JAM | ||

| Martinique (France) |

1,128 km2 (436 sq mi) |

368,796 | 352.6/km2 (913/sq mi) |

Fort-de-France | Martinique/Matinik | MTQ | ||

| Mexico | 1,964,375 km2 (758,449 sq mi) |

126,705,138 | 57.1/km2 (148/sq mi) |

Mexico City | México | MEX | ||

| Montserrat (United Kingdom) |

102 km2 (39 sq mi) |

4,417 | 58.8/km2 (152/sq mi) |

Plymouth, Brades[lower-alpha 5] |

Montserrat | MSR | ||

| Nicaragua | 130,373 km2 (50,337 sq mi) |

6,850,540 | 44.1/km2 (114/sq mi) |

Managua | Nicaragua | NIC | ||

| Nueva Esparta (Venezuela) |

1,151 km2 (444 sq mi) |

491,610 | 427.1/km2 (1,106/sq mi) |

La Asunción | Nueva Esparta | VEN-O | ||

| Panama[lower-alpha 3][lower-alpha 6] | 75,417 km2 (29,119 sq mi) |

4,351,267 | 45.8/km2 (119/sq mi) |

Panama City | Panamá | PAN | ||

| Puerto Rico (United States) |

8,870 km2 (3,420 sq mi) |

3,256,028 | 448.9/km2 (1,163/sq mi) |

San Juan | Puerto Rico | PRI | ||

| Saba (Kingdom of the Netherlands)[48] |

13 km2 (5.0 sq mi) |

1,537 | 118.2/km2 (306/sq mi) |

The Bottom | Saba | BES | ||

| San Andrés and Providencia (Colombia) |

53 km2 (20 sq mi) |

77,701 | 1,468.59/km2 (3,803.6/sq mi) |

San Andrés | San Andrés | COL-SAP | ||

| Saint Barthélemy (France)[49] |

21 km2 (8.1 sq mi)[50] |

7,448 | 354.7/km2 (919/sq mi) |

Gustavia | Saint-Barthélemy | BLM | ||

| Saint Kitts and Nevis | 261 km2 (101 sq mi) |

47,606 | 199.2/km2 (516/sq mi) |

Basseterre | Saint Kitts and Nevis | KNA | ||

| Saint Lucia | 539 km2 (208 sq mi) |

179,651 | 319.1/km2 (826/sq mi) |

Castries | Sainte-Lucie | LCA | ||

| Saint Martin (France)[49] |

54 km2 (21 sq mi)[50] |

29,820 | 552.2/km2 (1,430/sq mi) |

Marigot | Saint-Martin | MAF | ||

| Saint Pierre and Miquelon (France) |

242 km2 (93 sq mi) |

5,883 | 24.8/km2 (64/sq mi) |

Saint-Pierre | Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon | SPM | ||

| Saint Vincent and the Grenadines | 389 km2 (150 sq mi) |

104,332 | 280.2/km2 (726/sq mi) |

Kingstown | Saint Vincent and the Grenadines | VCT | ||

| Sint Eustatius (Kingdom of the Netherlands)[48] |

21 km2 (8.1 sq mi) |

2,739 | 130.4/km2 (338/sq mi) |

Oranjestad | Sint Eustatius | BES | ||

| Sint Maarten (Kingdom of the Netherlands) |

34 km2 (13 sq mi) |

44,042 | 1,176.7/km2 (3,048/sq mi) |

Philipsburg | Sint Maarten | SXM | ||

| Trinidad and Tobago[lower-alpha 3] | 5,130 km2 (1,980 sq mi) |

1,525,663 | 261.0/km2 (676/sq mi) |

Port of Spain | Trinidad and Tobago | TTO | ||

| Turks and Caicos Islands (United Kingdom)[lower-alpha 7] |

948 km2 (366 sq mi) |

45,114 | 34.8/km2 (90/sq mi) |

Grand Turk (Cockburn Town) | Turks and Caicos Islands | TCA | ||

| United States[lower-alpha 8] | 9,629,091 km2 (3,717,813 sq mi) |

336,997,624 | 32.7/km2 (85/sq mi) |

Washington, D.C. | United States of America | USA | ||

| United States Virgin Islands (United States) |

347 km2 (134 sq mi) |

100,091 | 317.0/km2 (821/sq mi) |

Charlotte Amalie | US Virgin Islands | VIR | ||

| Total | 24,500,995 km2 (9,459,887 sq mi) |

583,473,912 | 22.1/km2 (57/sq mi) |

|||||

Natural characteristics

Geography

North America occupies the northern portion of the landmass generally referred to as the New World, the Western Hemisphere, the Americas, or simply America (which, in many countries is considered as a single continent[51][52][53] with North America a subcontinent).[54][55][56] North America is the third-largest continent by area, following Asia and Africa.[57][58] North America's only land connection to South America is at the Isthmus of Darian/Isthmus of Panama. The continent is delimited on the southeast by most geographers at the Darién watershed along the Colombia-Panama border, placing almost all of Panama within North America.[59][60][61] Alternatively, some geologists physiographically locate its southern limit at the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, Mexico, with Central America extending southeastward to South America from this point.[62] The Caribbean islands, or West Indies, are considered part of North America.[55] The continental coastline is long and irregular. The Gulf of Mexico is the largest body of water indenting the continent, followed by Hudson Bay. Others include the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and the Gulf of California.

Before the Central American isthmus formed, the region had been underwater. The islands of the West Indies delineate a submerged former land bridge, which had connected North and South America via what are now Florida and Venezuela.

There are numerous islands off the continent's coasts; principally, the Arctic Archipelago, the Bahamas, Turks & Caicos, the Greater and Lesser Antilles, the Aleutian Islands (some of which are in the Eastern Hemisphere proper), the Alexander Archipelago, the many thousand islands of the British Columbia Coast, and Newfoundland. Greenland, a self-governing Danish island, and the world's largest, is on the same tectonic plate (the North American Plate) and is part of North America geographically. In a geologic sense, Bermuda is not part of the Americas, but an oceanic island that was formed on the fissure of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge over 100 million years ago. The nearest landmass to it is Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. However, Bermuda is often thought of as part of North America, especially given its historical, political and cultural ties to Virginia and other parts of the continent.

The vast majority of North America is on the North American Plate. Parts of western Mexico, including Baja California, and of California, including the cities of San Diego, Los Angeles, and Santa Cruz, lie on the eastern edge of the Pacific Plate, with the two plates meeting along the San Andreas fault. The southernmost portion of the continent and much of the West Indies lie on the Caribbean Plate, whereas the Juan de Fuca and Cocos plates border the North American Plate on its western frontier.

The continent can be divided into four great regions (each of which contains many subregions): the Great Plains stretching from the Gulf of Mexico to the Canadian Arctic; the geologically young, mountainous west, including the Rocky Mountains, the Great Basin, California and Alaska; the raised but relatively flat plateau of the Canadian Shield in the northeast; and the varied eastern region, which includes the Appalachian Mountains, the coastal plain along the Atlantic seaboard, and the Florida peninsula. Mexico, with its long plateaus and cordilleras, falls largely in the western region, although the eastern coastal plain does extend south along the Gulf.

The western mountains are split in the middle into the main range of the Rockies and the coast ranges in California, Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia, with the Great Basin—a lower area containing smaller ranges and low-lying deserts—in between. The highest peak is Denali in Alaska.

The United States Geographical Survey (USGS) states that the geographic center of North America is "6 miles [10 km] west of Balta, Pierce County, North Dakota" at about 48°10′N 100°10′W, about 24 kilometres (15 mi) from Rugby, North Dakota. The USGS further states that "No marked or monumented point has been established by any government agency as the geographic center of either the 50 States, the conterminous United States, or the North American continent." Nonetheless, there is a 4.6-metre (15 ft) field stone obelisk in Rugby claiming to mark the center. The North American continental pole of inaccessibility is located 1,650 km (1,030 mi) from the nearest coastline, between Allen and Kyle, South Dakota at 43.36°N 101.97°W.[63]

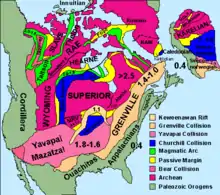

Geologic history

Laurentia is an ancient craton which forms the geologic core of North America; it formed between 1.5 and 1.0 billion years ago during the Proterozoic eon.[64] The Canadian Shield is the largest exposure of this craton. From the Late Paleozoic to Early Mesozoic eras, North America was joined with the other modern-day continents as part of the supercontinent Pangaea, with Eurasia to its east. One of the results of the formation of Pangaea was the Appalachian Mountains, which formed some 480 million years ago, making it among the oldest mountain ranges in the world. When Pangaea began to rift around 200 million years ago, North America became part of Laurasia, before it separated from Eurasia as its own continent during the mid-Cretaceous period.[65] The Rockies and other western mountain ranges began forming around this time from a period of mountain building called the Laramide orogeny, between 80 and 55 million years ago. The formation of the Isthmus of Panama that connected the continent to South America arguably occurred approximately 12 to 15 million years ago,[66] and the Great Lakes (as well as many other northern freshwater lakes and rivers) were carved by receding glaciers about 10,000 years ago.

North America is the source of much of what humanity knows about geologic time periods.[67] The geographic area that would later become the United States has been the source of more varieties of dinosaurs than any other modern country.[67] According to paleontologist Peter Dodson, this is primarily due to stratigraphy, climate and geography, human resources, and history.[67] Much of the Mesozoic Era is represented by exposed outcrops in the many arid regions of the continent.[67] The most significant Late Jurassic dinosaur-bearing fossil deposit in North America is the Morrison Formation of the western United States.[68]

Canadian geology

Geologically, Canada is one of the oldest regions in the world, with more than half of the region consisting of precambrian rocks that have been above sea level since the beginning of the Palaeozoic era.[69] Canada's mineral resources are diverse and extensive.[69] Across the Canadian Shield and in the north there are large iron, nickel, zinc, copper, gold, lead, molybdenum, and uranium reserves. Large diamond concentrations have been recently developed in the Arctic,[70] making Canada one of the world's largest producers. Throughout the Shield, there are many mining towns extracting these minerals. The largest, and best known, is Sudbury, Ontario. Sudbury is an exception to the normal process of forming minerals in the Shield since there is significant evidence that the Sudbury Basin is an ancient meteorite impact crater. The nearby, but less known Temagami Magnetic Anomaly has striking similarities to the Sudbury Basin. Its magnetic anomalies are very similar to the Sudbury Basin, and so it could be a second metal-rich impact crater.[71] The Shield is also covered by vast boreal forests that support an important logging industry.

United States geology

The lower 48 US states can be divided into roughly five physiographic provinces:

- The American cordillera

- The Canadian Shield[69] Northern portion of the upper midwestern United States.

- The stable platform

- The coastal plain

- The Appalachian orogenic belt

The geology of Alaska is typical of that of the cordillera, while the major islands of Hawaii consist of Neogene volcanics erupted over a hot spot.

Central American geology

Central America is geologically active with volcanic eruptions and earthquakes occurring from time to time. In 1976 Guatemala was hit by a major earthquake, killing 23,000 people; Managua, the capital of Nicaragua, was devastated by earthquakes in 1931 and 1972, the last one killing about 5,000 people; three earthquakes devastated El Salvador, one in 1986 and two in 2001; one earthquake devastated northern and central Costa Rica in 2009, killing at least 34 people; in Honduras a powerful earthquake killed seven people in 2009.

Volcanic eruptions are common in the region. In 1968 the Arenal Volcano, in Costa Rica, erupted and killed 87 people. Fertile soils from weathered volcanic lavas have made it possible to sustain dense populations in agriculturally productive highland areas.

Central America has many mountain ranges; the longest are the Sierra Madre de Chiapas, the Cordillera Isabelia, and the Cordillera de Talamanca. Between the mountain ranges lie fertile valleys that are suitable for the people; in fact, most of the population of Honduras, Costa Rica, and Guatemala live in valleys. Valleys are also suitable for the production of coffee, beans, and other crops.

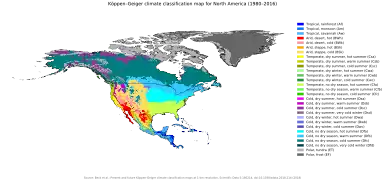

Climate

North America is a very large continent that extends from north of the Arctic Circle to south of the Tropic of Cancer. Greenland, along with the Canadian Shield, is tundra with average temperatures ranging from 10 to 20 °C (50 to 68 °F), but central Greenland is composed of a very large ice sheet. This tundra radiates throughout Canada, but its border ends near the Rocky Mountains (but still contains Alaska) and at the end of the Canadian Shield, near the Great Lakes. Climate west of the Cascade Range is described as being temperate weather with average precipitation 20 inches (510 mm).[72] Climate in coastal California is described to be Mediterranean, with average temperatures in cities like San Francisco ranging from 57 to 70 °F (14 to 21 °C) over the course of the year.[73]

Stretching from the East Coast to eastern North Dakota, and stretching down to Kansas, is the humid continental climate featuring intense seasons, with a large amount of annual precipitation, with places like New York City averaging 50 inches (1,300 mm).[74] Starting at the southern border of the humid continental climate and stretching to the Gulf of Mexico (whilst encompassing the eastern half of Texas) is the humid subtropical climate. This area has the wettest cities in the contiguous United States, with annual precipitation reaching 67 inches (1,700 mm) in Mobile, Alabama.[75] Stretching from the borders of the humid continental and subtropical climates, and going west to the Sierra Nevada, south to the southern tip of Durango, north to the border with tundra climate, the steppe/desert climates are the driest in the United States.[76] Highland climates cut from north to south of the continent, where subtropical or temperate climates occur just below the tropics, as in central Mexico and Guatemala. Tropical climates appear in the island regions and in the subcontinent's bottleneck. Precipitation patterns vary across the region, and as such rainforest, monsoon, and savanna types can be found, with rains and high temperatures throughout the year. Found in countries and states bathed by the Caribbean Sea or to the south of the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific Ocean.[77]

Ecology

Notable North American fauna include the bison, black bear, jaguar, cougar, prairie dog, turkey, pronghorn, raccoon, coyote and monarch butterfly.

Notable plants that were domesticated in North America include tobacco, maize, squash, tomato, sunflower, blueberry, avocado, cotton, chile pepper and vanilla.

History

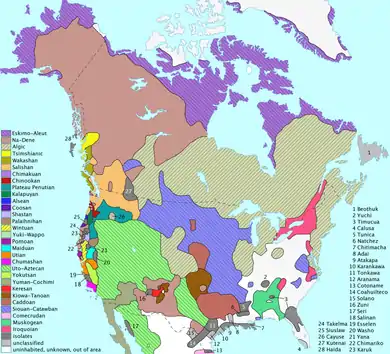

Pre-Columbian

The indigenous peoples of the Americas have many creation myths by which they assert that they have been present on the land since its creation,[78] but there is no evidence that humans evolved there.[79] The specifics of the initial settlement of the Americas by ancient Asians are subject to ongoing research and discussion.[80] The traditional theory has been that hunters entered the Bering Land Bridge between eastern Siberia and present-day Alaska from 27,000 to 14,000 years ago.[81][82][lower-alpha 9] A growing viewpoint is that the first American inhabitants sailed from Beringia some 13,000 years ago,[84] with widespread habitation of the Americas during the end of the Last Glacial Period, in what is known as the Late Glacial Maximum, around 12,500 years ago.[85] The oldest petroglyphs in North America date from 15,000 to 10,000 years before present.[86][lower-alpha 10] Genetic research and anthropology indicate additional waves of migration from Asia via the Bering Strait during the Early-Middle Holocene.[88][89][90]

Before contact with Europeans, the natives of North America were divided into many different polities, from small bands of a few families to large empires. They lived in several "culture areas", which roughly correspond to geographic and biological zones and give a good indication of the main way of life of the people who lived there (e.g., the bison hunters of the Great Plains, or the farmers of Mesoamerica). Native groups can also be classified by their language family (e.g., Athapascan or Uto-Aztecan). Peoples with similar languages did not always share the same material culture, nor were they always allies. Anthropologists think that the Inuit of the high Arctic came to North America much later than other native groups, as evidenced by the disappearance of Dorset culture artifacts from the archaeological record, and their replacement by the Thule people.

During the thousands of years of native habitation on the continent, cultures changed and shifted. One of the oldest yet discovered is the Clovis culture (c. 9550–9050 BCE) in modern New Mexico.[87] Later groups include the Mississippian culture and related Mound building cultures, found in the Mississippi river valley and the Pueblo culture of what is now the Four Corners. The more southern cultural groups of North America were responsible for the domestication of many common crops now used around the world, such as tomatoes, squash, and maize. As a result of the development of agriculture in the south, many other cultural advances were made there. The Mayans developed a writing system, built huge pyramids and temples, had a complex calendar, and developed the concept of zero around 400 CE.[91]

The first recorded European references to North America are in Norse sagas where it is referred to as Vinland.[92] The earliest verifiable instance of pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact by any European culture with the North America mainland has been dated to around 1000 CE.[93] The site, situated at the northernmost extent of the island named Newfoundland, has provided unmistakable evidence of Norse settlement.[94] Norse explorer Leif Erikson (c. 970–1020 CE) is thought to have visited the area.[lower-alpha 11] Erikson was the first European to make landfall on the continent (excluding Greenland).[96][97]

The Mayan culture was still present in southern Mexico and Guatemala when the Spanish conquistadors arrived, but political dominance in the area had shifted to the Aztec Empire, whose capital city Tenochtitlan was located further north in the Valley of Mexico. The Aztecs were conquered in 1521 by Hernán Cortés.[98]

Post-contact, 1492–1910

During the so-called Age of Discovery, Europeans explored overseas and staked claims to various parts of North America, much of which was already settled by indigenous peoples. Upon Europeans' arrival in the "New World", indigenous peoples had a variety of reactions, including curiosity, trading, cooperation, resignation, and resistance. The indigenous population declined substantially following European arrival, primarily due to the introduction of Eurasian diseases, such as smallpox, to which the indigenous peoples lacked immunity, and because of violent conflicts with Europeans.[99] Indigenous culture changed significantly and their affiliation with political and cultural groups also changed. Several linguistic groups died out, and others changed quite quickly.

On the southern eastcoast of North America, Spanish explorer Juan Ponce de León, who had accompanied Columbus's second voyage, visited and named in 1513 La Florida.[100] As the colonial period unfolded, Spain, England, and France appropriated and claimed extensive territories in North America eastern and southern coastlines. Spain established permanent settlements on the Caribbean islands of Hispaniola and Cuba in the 1490s, building cities, putting the resident indigenous populations to work, raising crops for Spanish settlers and panning gold to enrich the Spaniards. Much of the indigenous population died due to disease and overwork, spurring the Spaniards on the claim new lands and peoples. An expedition under the command of Spanish settler, Hernán Cortés, sailed westward in 1519 to what turned out to be the mainland in Mexico. With local indigenous allies, the Spanish conquered the Aztec empire in central Mexico in 1521. Spain then established permanent cities in Mexico, Central America, and Spanish South America in the sixteenth century. Once Spaniards conquered the high civilization of the Aztecs and Incas, the Caribbean was a backwater of the Spanish empire.

Other European powers began to intrude on areas that Spain had claimed, including the Caribbean islands. France took the western half of Hispaniola and developed Saint-Domingue as a cane sugar producing colony worked by black slave labor. Britain took Barbados and Jamaica; the Dutch and Danes also took islands previous claimed by Spain. Britain did not begin settling on the North American mainland until a hundred years after the first Spanish settlements, since it sought first to control nearby Ireland. The first permanent English settlement was in Jamestown, Virginia in 1607, and then further settler colonial establishments on the east coast of the continent from is now Georgia up to Massachusetts, forming the Thirteen Colonies. The English did not establish settlements north, east of the St. Lawrence Valley in what would become Canada until well after the war of independence. English early permanent settlements were St. John's, Newfoundland in 1630 and Halifax, Nova Scotia in 1749. The first permanent French settlement was in Quebec City, Quebec in 1608. In the British victory the Seven Years' War, France ceded to Britain its claims east of the Mississippi River in 1763. Spain gained rights to the territories west of Mississippi now acting as a border. French so-called "colonists" that had first settled the Illinois Country after several generations of experience on the new continent migrated over the Mississippi in the absence of Spanish occupants while leveraging earlier Louisiana French settlements around the Gulf of Mexico. These early French settlers partnering with midwest indigenous tribes and their mixed ancestry descendants would precede the westward push and guide through waves of followers all the way to the Pacific.

In the late 18th and early the Thirteen Colonies on the North Atlantic coast declared independence in 1776, fighting a protracted war of independence with the aid of Britain's enemies France and Spain, becoming the United States of America. The new nation steadily attempted to increase its territory. By that time, Russians were already well established on the Pacific Northwest northern coastline with Maritime Fur Trade activities supported by active settlements. As a result, Spanish were showing more interest in controlling the trade on the Pacific coast and mapped most of its coastline. The first Spanish settlements were attempted in Alta California during that period. Numerous overland explorations associated with Voyageurs, Fur Trade, and United States led expeditions (e.g. Lewis and Clark, Fremont and Wilkes) were reaching the Pacific at various latitudes around the turn of the century. In 1803 Napoleon Bonaparte sold France's remaining claims in North America, west of the Mississippi River, to the United States, in a deal named the Louisiana Purchase. Spain and the United States settled their western boundary dispute in 1819 in the Adams-Onís Treaty. Mexico fought a lengthy war for independence from Spain, winning it for Mexico and Central American in 1821. The U.S. sought further westward expansion and fought the Mexican-American War, gaining a vast territory that first Spain and then Mexico claimed but which they did not effectively control. Much of the area was in fact dominated by indigenous peoples, which did not recognize the claims of Spain, France, or the United States. Russia sold its North American claims, which included Alaska, to the U.S. in 1867. Also in 1867, settler colonies in eastern North America, were unified as the dominion of Canada. The U.S. sought to dig a canal across the Isthmus of Panama, a part of Colombia, and aided Panamanians in a war to separate it from Colombia. The U.S. carved out the Panama Canal Zone, over which it claimed sovereignty. After decades of work on the Panama Canal was completed, connecting the Atlantic and Pacific oceans in 1913.

Demographics

Economically, Canada and the United States are the wealthiest and most developed nations in the continent, followed by Mexico, a newly industrialized country.[101] The countries of Central America and the Caribbean are at various levels of economic and human development. For example, small Caribbean island-nations, such as Barbados, Trinidad and Tobago, and Antigua and Barbuda, have a higher GDP (PPP) per capita than Mexico due to their smaller populations. Panama and Costa Rica have a significantly higher Human Development Index and GDP than the rest of the Central American nations.[102] Additionally, despite Greenland's vast resources in oil and minerals, much of them remain untapped, and the island is economically dependent on fishing, tourism, and subsidies from Denmark. Nevertheless, the island is highly developed.[103]

Demographically, North America is ethnically diverse. Its three main groups are Whites, Mestizos and Blacks.[104] There is a significant minority of Indigenous Americans and Asians among other less numerous groups.[104]

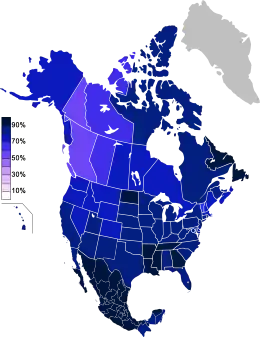

Languages

The dominant languages in North America are English, Spanish, and French. Danish is prevalent in Greenland alongside Greenlandic, and Dutch is spoken side by side local languages in the Dutch Caribbean. The term Anglo-America is used to refer to the anglophone countries of the Americas: namely Canada (where English and French are co-official) and the United States, but also sometimes Belize and parts of the tropics, especially the Commonwealth Caribbean. Latin America refers to the other areas of the Americas (generally south of the United States) where the Romance languages, derived from Latin, of Spanish and Portuguese, (but French-speaking countries are not usually included) predominate: the other republics of Central America (but not always Belize), part of the Caribbean (not the Dutch-, English-, or French-speaking areas), Mexico, and most of South America (except Guyana, Suriname, French Guiana (France), and the Falkland Islands (UK)).

The French language has historically played a significant role in North America and now retains a distinctive presence in some regions. Canada is officially bilingual. French is the official language of the Province of Quebec, where 95% of the people speak it as either their first or second language, and it is co-official with English in the Province of New Brunswick. Other French-speaking locales include the Province of Ontario (the official language is English, but there are an estimated 600,000 Franco-Ontarians), the Province of Manitoba (co-official as de jure with English), the French West Indies and Saint-Pierre et Miquelon, as well as the US state of Louisiana, where French is also an official language. Haiti is included with this group based on historical association but Haitians speak both Creole and French. Similarly, French and French Antillean Creole is spoken in Saint Lucia and the Commonwealth of Dominica alongside English.

A significant number of Indigenous languages are spoken in North America, with 372,000 people in the United States speaking an indigenous language at home,[105] about 225,000 in Canada[106] and roughly 6 million in Mexico.[107] In the United States and Canada, there are approximately 150 surviving indigenous languages of the 300 spoken prior to European contact.[108]

Religions

Christianity is the largest religion in the United States, Canada and Mexico. According to a 2012 Pew Research Center survey, 77% of the population considered themselves Christians.[109] Christianity also is the predominant religion in the 23 dependent territories in North America.[110] The United States has the largest Christian population in the world, with nearly 247 million Christians (70%), although other countries have higher percentages of Christians among their populations.[111] Mexico has the world's second largest number of Catholics, surpassed only by Brazil.[112] A 2015 study estimates about 493,000 Christian believers from a Muslim background in North America, most of them belonging to some form of Protestantism.[113]

According to the same study, the religiously unaffiliated (including agnostics and atheists) make up about 17% of the population of Canada and the United States.[114] Those with no religious affiliation make up about 24% of the United States population, and 24% of Canada's total population.[115]

Canada, the United States and Mexico host communities of Jews (6 million or about 1.8%),[116] Buddhists (3.8 million or 1.1%)[117] and Muslims (3.4 million or 1.0%).[118] The largest number of Jews can be found in the United States (5.4 million),[119] Canada (375,000)[120] and Mexico (67,476).[121] The United States hosts the largest Muslim population in North America with 2.7 million or 0.9%,[122][123] While Canada host about one million Muslim or 3.2% of the population.[124] While in Mexico there were 3,700 Muslims in the country.[125] In 2012, U-T San Diego estimated U.S. practitioners of Buddhism at 1.2 million people, of whom 40% are living in Southern California.[126]

The predominant religion in Mexico and Central America is Christianity (96%).[127] Beginning with the Spanish colonization of Mexico in the 16th century, Roman Catholicism was the only religion permitted by Spanish crown and Catholic church. A vast campaign of religious conversion, the so-called "spiritual conquest", was launched to bring indigenous into the Christian fold. The Inquisition was established to assure orthodox belief and practice. The Catholic Church remained an important institution, so that even after political independence, Roman Catholicism remained the dominant religion. Since the 1960s, there has been an increase in other Christian groups, particularly Protestantism, as well as other religious organizations, and individuals identifying themselves as having no religion. Also Christianity is the predominant religion in the Caribbean (85%).[127] Other religious groups in the region are Hinduism, Islam, Rastafari (in Jamaica), and Afro-American religions such as Santería and Vodou.

Populace

North America is the fourth most populous continent after Asia, Africa, and Europe.[128] Its most populous country is the United States with 329.7 million persons. The second largest country is Mexico with a population of 112.3 million.[129] Canada is the third most populous country with 37.0 million.[130] The majority of Caribbean island-nations have national populations under a million, though Cuba, Dominican Republic, Haiti, Puerto Rico (a territory of the United States), Jamaica, and Trinidad and Tobago each have populations higher than a million.[131][132][133][134][135] Greenland has a small population of 55,984 for its massive size (2,166,000 km2 or 836,300 mi2), and therefore, it has the world's lowest population density at 0.026 pop./km2 (0.067 pop./mi2).[136]

While the United States, Canada, and Mexico maintain the largest populations, large city populations are not restricted to those nations. There are also large cities in the Caribbean. The largest cities in North America, by far, are Mexico City and New York. These cities are the only cities on the continent to exceed eight million, and two of three in the Americas. Next in size are Los Angeles, Toronto,[137] Chicago, Havana, Santo Domingo, and Montreal. Cities in the sun belt regions of the United States, such as those in Southern California and Houston, Phoenix, Miami, Atlanta, and Las Vegas, are experiencing rapid growth. These causes included warm temperatures, retirement of Baby Boomers, large industry, and the influx of immigrants. Cities near the United States border, particularly in Mexico, are also experiencing large amounts of growth. Most notable is Tijuana, a city bordering San Diego that receives immigrants from all over Latin America and parts of Europe and Asia. Yet as cities grow in these warmer regions of North America, they are increasingly forced to deal with the major issue of water shortages.[138]

Eight of the top ten metropolitan areas are located in the United States. These metropolitan areas all have a population of above 5.5 million and include the New York City metropolitan area, Los Angeles metropolitan area, Chicago metropolitan area, and the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex.[139] Whilst the majority of the largest metropolitan areas are within the United States, Mexico is host to the largest metropolitan area by population in North America: Greater Mexico City.[140] Canada also breaks into the top ten largest metropolitan areas with the Toronto metropolitan area having six million people.[141] The proximity of cities to each other on the Canada–United States border and Mexico–United States border has led to the rise of international metropolitan areas. These urban agglomerations are observed at their largest and most productive in Detroit–Windsor and San Diego–Tijuana and experience large commercial, economic, and cultural activity. The metropolitan areas are responsible for millions of dollars of trade dependent on international freight. In Detroit-Windsor the Border Transportation Partnership study in 2004 concluded US$13 billion was dependent on the Detroit–Windsor international border crossing while in San Diego-Tijuana freight at the Otay Mesa Port of Entry was valued at US$20 billion.[142][143]

North America has also been witness to the growth of megapolitan areas. In the United States exists eleven megaregions that transcend international borders and comprise Canadian and Mexican metropolitan regions. These are the Arizona Sun Corridor, Cascadia, Florida, Front Range, Great Lakes Megalopolis, Gulf Coast, Northeast, Northern California, Piedmont Atlantic, Southern California, and the Texas Triangle.[144] Canada and Mexico are also the home of megaregions. These include the Quebec City – Windsor Corridor, Golden Horseshoe – both of which are considered part of the Great Lakes Megalopolis – and the Central Mexico megalopolis. Traditionally the largest megaregion has been considered the Boston-Washington, DC Corridor, or the Northeast, as the region is one massive contiguous area. Yet megaregion criterion have allowed the Great Lakes Megalopolis to maintain status as the most populated region, being home to 53,768,125 people in 2000.[145]

The top ten largest North American metropolitan areas by population as of 2013, based on national census numbers from the United States and census estimates from Canada and Mexico.

| Metro Area | Population | Area | Country |

| Mexico City | 21,163,226† | 7,346 km2 (2,836 sq mi) | Mexico |

| New York City | 19,949,502 | 17,405 km2 (6,720 sq mi) | United States |

| Los Angeles | 13,131,431 | 12,562 km2 (4,850 sq mi) | United States |

| Chicago | 9,537,289 | 24,814 km2 (9,581 sq mi) | United States |

| Dallas–Fort Worth | 6,810,913 | 24,059 km2 (9,289 sq mi) | United States |

| Houston | 6,313,158 | 26,061 km2 (10,062 sq mi) | United States |

| Toronto | 6,054,191† | 5,906 km2 (2,280 sq mi) | Canada |

| Philadelphia | 6,034,678 | 13,256 km2 (5,118 sq mi) | United States |

| Washington, DC | 5,949,859 | 14,412 km2 (5,565 sq mi) | United States |

| Miami | 5,828,191 | 15,896 km2 (6,137 sq mi) | United States |

†2011 Census figures.

Economy

| Rank | Country or Territory | GDP[146](PPP, peak year) millions of USD |

Peak year |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 25,346,805 | 2022 | |

| 2 | 2,890,685 | 2022 | |

| 3 | 2,236,928 | 2022 | |

| 4 | 254,992 | 2022 | |

| 5 | 254,865 | 2015 | |

| 6 | 185,473 | 2022 | |

| 7 | 158,608 | 2022 | |

| 8 | 132,001 | 2022 | |

| 9 | 128,134 | 2022 | |

| 10 | 69,388 | 2022 |

| Rank | Country or Territory | GDP (nominal, peak year) millions of USD |

Peak year |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 25,346,805 | 2022 | |

| 2 | 2,221,218 | 2022 | |

| 3 | 1,322,740 | 2022 | |

| 4 | 116,762 | 2022 | |

| 5 | 109,080 | 2022 | |

| 6 | 107,352 | 2020 | |

| 7 | 91,019 | 2022 | |

| 8 | 70,492 | 2022 | |

| 9 | 65,314 | 2022 | |

| 10 | 30,720 | 2022 |

North America's GDP per capita was evaluated in October 2016 by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to be $41,830, making it the richest continent in the world,[148] followed by Oceania.[149]

Canada, Mexico, and the United States have significant and multifaceted economic systems. The United States has the largest economy of all three countries and in the world.[149] In 2016, the U.S. had an estimated per capita gross domestic product (PPP) of $57,466 according to the World Bank, and is the most technologically developed economy of the three.[150] The United States' services sector comprises 77% of the country's GDP (estimated in 2010), industry comprises 22% and agriculture comprises 1.2%.[149] The U.S. economy is also the fastest growing economy in North America and the Americas as a whole,[151][148] with the highest GDP per capita in the Americas as well.[148]

.jpg.webp)

Canada shows significant growth in the sectors of services, mining and manufacturing.[152] Canada's per capita GDP (PPP) was estimated at $44,656 and it had the 11th largest GDP (nominal) in 2014.[152] Canada's services sector comprises 78% of the country's GDP (estimated in 2010), industry comprises 20% and agriculture comprises 2%.[152] Mexico has a per capita GDP (PPP) of $16,111 and as of 2014 is the 15th largest GDP (nominal) in the world.[153] Being a newly industrialized country,[101] Mexico maintains both modern and outdated industrial and agricultural facilities and operations.[154] Its main sources of income are oil, industrial exports, manufactured goods, electronics, heavy industry, automobiles, construction, food, banking and financial services.[155]

The North American economy is well defined and structured in three main economic areas.[156] These areas are the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), Caribbean Community and Common Market (CARICOM), and the Central American Common Market (CACM).[156] Of these trade blocs, the United States takes part in two. In addition to the larger trade blocs there is the Canada-Costa Rica Free Trade Agreement among numerous other free trade relations, often between the larger, more developed countries and Central American and Caribbean countries.

The North America Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) forms one of the four largest trade blocs in the world.[157] Its implementation in 1994 was designed for economic homogenization with hopes of eliminating barriers of trade and foreign investment between Canada, the United States and Mexico.[158] While Canada and the United States already conducted the largest bilateral trade relationship – and to present day still do – in the world and Canada–United States trade relations already allowed trade without national taxes and tariffs,[159] NAFTA allowed Mexico to experience a similar duty-free trade. The free trade agreement allowed for the elimination of tariffs that had previously been in place on United States-Mexico trade. Trade volume has steadily increased annually and in 2010, surface trade between the three NAFTA nations reached an all-time historical increase of 24.3% or US$791 billion.[160] The NAFTA trade bloc GDP (PPP) is the world's largest with US$17.617 trillion.[161] This is in part attributed to the fact that the economy of the United States is the world's largest national economy; the country had a nominal GDP of approximately $14.7 trillion in 2010.[162] The countries of NAFTA are also some of each other's largest trade partners. The United States is the largest trade partner of Canada and Mexico;[163] while Canada and Mexico are each other's third largest trade partners.[164][165]

%252C_2018.jpg.webp)

The Caribbean trade bloc – CARICOM – came into agreement in 1973 when it was signed by 15 Caribbean nations. As of 2000, CARICOM trade volume was US$96 billion. CARICOM also allowed for the creation of a common passport for associated nations. In the past decade the trade bloc focused largely on Free Trade Agreements and under the CARICOM Office of Trade Negotiations (OTN) free trade agreements have been signed into effect.

Integration of Central American economies occurred under the signing of the Central American Common Market agreement in 1961; this was the first attempt to engage the nations of this area into stronger financial cooperation. The recent implementation of the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA) has left the future of the CACM unclear.[166] The Central American Free Trade Agreement was signed by five Central American countries, the Dominican Republic, and the United States. The focal point of CAFTA is to create a free trade area similar to that of NAFTA. In addition to the United States, Canada also has relations in Central American trade blocs. Currently under proposal, the Canada – Central American Free Trade Agreement (CA4) would operate much the same as CAFTA with the United States does.

These nations also take part in inter-continental trade blocs. Mexico takes a part in the G3 Free Trade Agreement with Colombia and Venezuela and has a trade agreement with the EU. The United States has proposed and maintained trade agreements under the Transatlantic Free Trade Area between itself and the European Union; the US-Middle East Free Trade Area between numerous Middle Eastern nations and itself; and the Trans-Pacific Strategic Economic Partnership between Southeast Asian nations, Australia, and New Zealand.

Transport

The Pan-American Highway route in the Americas is the portion of a network of roads nearly 48,000 km (30,000 mi) in length which travels through the mainland nations. No definitive length of the Pan-American Highway exists because the US and Canadian governments have never officially defined any specific routes as being part of the Pan-American Highway, and Mexico officially has many branches connecting to the US border. However, the total length of the portion from Mexico to the northern extremity of the highway is roughly 26,000 km (16,000 mi).

The First Transcontinental Railroad in the United States was built in the 1860s, linking the railroad network of the eastern US with California on the Pacific coast. Finished on 10 May 1869 at the famous golden spike event at Promontory Summit, Utah, it created a nationwide mechanized transportation network that revolutionized the population and economy of the American West, catalyzing the transition from the wagon trains of previous decades to a modern transportation system.[167] Although an accomplishment, it achieved the status of first transcontinental railroad by connecting myriad eastern US railroads to the Pacific and was not the largest single railroad system in the world. The Canadian Grand Trunk Railway (GTR) had, by 1867, already accumulated more than 2,055 km (1,277 mi) of track by connecting Ontario with the Canadian Atlantic provinces west as far as Port Huron, Michigan, through Sarnia, Ontario.

Communications

A shared telephone system known as the North American Numbering Plan (NANP) is an integrated telephone numbering plan of 24 countries and territories: the United States and its territories, Canada, Bermuda, and 17 Caribbean nations.

Culture

The cultures of North America are diverse. The United States and English Canada have many cultural similarities, while French Canada has a distinct culture from Anglophone Canada, which is protected by law. Since United States was formed from portions previously part of the Spanish Empire and then independent Mexico, and there has been considerable and continuing immigration of Spanish speakers from south of the U.S.-Mexico border. In the southwest of the U.S. there are many Hispanic cultural traditions and considerable bilingualism. Mexico and Central America are part of Latin America and are culturally distinct from anglophone and francophone North America. However, they share with the United States the establishment of post-independence governments that are federated representative republics with written constitutions dating from their founding as nations. Canada is a federated parliamentary democracy under a constitutional monarchy.

Canada's constitution dates to 1867, with confederation, in the British North America Act, but not until 1982 did Canada have the power to amend its own constitution. Canada's Francophone heritage has been enshrined in law since the British parliament passed the Quebec Act of 1774. In contrast to largely Protestant Anglo settlers in North America, French-speaking Canadians were Catholic and with the Quebec Act were guaranteed freedom to practice their religion, restored the right of the Catholic Church to impose tithes for its support, and established French civil law in most circumstances.

The distinctiveness of French language and culture has been codified in Canadian law, so that both English and French are designated official languages. The U.S. has no official language, but its national language is English.

The Canadian government took action to protect Canadian culture by limiting non-Canadian content in broadcasting, creating the Canadian Radio and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) to monitor Canadian content. In Quebec, the provincial government established the Quebec Office of the French Language, often called the "language police" by Anglophones, which mandates the use of French terminology and signage in French.[168] Since 1968 the unicameral legislature has been called the Quebec National Assembly. Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day, June 24, is the national holiday of Quebec and celebrated by francophone Canadians throughout Canada. In Quebec, the school system was divided into Catholic and Protestant, so-called confessional schools. Anglophone education in Quebec has been increasingly undermined.[169]

Latino culture is strong in the southwest of the U.S., as well as Florida, which draws Latin Americans from many countries in the hemisphere. Northern Mexico, particularly in the cities of Monterrey, Tijuana, Ciudad Juárez, and Mexicali, is strongly influenced by the culture and way of life of the United States. Monterrey, a modern city with a significant industrial group, has been regarded as the most Americanized city in Mexico.[170] Northern Mexico, the Western United States and Alberta, Canada share a cowboy culture.

The Anglophone Caribbean states have witnessed and participated in the decline of the British Empire and its influence on the region, and its replacement by the economic influence of Northern America in the Anglophone Caribbean. This is partly due to the relatively small populations of the English-speaking Caribbean countries, and also because many of them now have more people living abroad than those remaining at home.

Greenland has experienced many immigration waves from Northern Canada, e .g. the Thule People. Therefore, Greenland shares some cultural ties with the indigenous peoples of Canada. Greenland is also considered Nordic and has strong Danish ties due to centuries of colonization by Denmark.[171]

Popular culture – sports

The U.S. and Canada have major sports teams that compete against each other, including baseball, basketball, hockey, and soccer/football. Canada, Mexico and the US submitted a joint bid to host the 2026 FIFA World Cup. The following table shows the most prominent sports leagues in North America, in order of average revenue.[172][173] Canada has a separate Canadian Football League from the U.S. teams.

The Native American game of lacrosse is considered a national sport in Canada. Curling is an important winter sport in Canada, and the Winter Olympics includes it in the roster. The English sport of cricket is popular in parts of anglophone Canada and very popular in parts of the former British empire, but in Canada is considered a minor sport. Boxing is also a major sport in some countries, such as Mexico, Panama and Puerto Rico, and it's considered one of the main individual sports in the United States.

| League | Sport | Primary country | Founded | Teams | Revenue US$ (bn) | Average attendance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National Football League (NFL) | American football | United States | 1920 | 32 | $9.0 | 67,604 |

| Major League Baseball (MLB) | Baseball | United States Canada | 1869 | 30 | $8.0 | 30,458 |

| National Basketball Association (NBA) | Basketball | United States Canada | 1946 | 30 | $5.0 | 17,347 |

| National Hockey League (NHL) | Ice hockey | United States Canada | 1917 | 32 | $3.3 | 17,720 |

| Liga MX | Football (soccer) | Mexico | 1943 | 18 | $0.6 | 25,557 |

| Major League Soccer (MLS) | Football (soccer) | United States Canada | 1994 | 28 | $0.5 | 21,574 |

| Canadian Football League (CFL) | Canadian football | Canada | 1958 | 9 | $0.3 | 23,890 |

See also

- North American Union

- United States of America

- Flags of North America

- List of cities in North America

- Outline of North America

- Table manners in North America

References

Footnotes

- This North American density figure is based on a total land area of 23,090,542 km2 only, considerably less than the total combined land and water area of 24,709,000 km2.

- Some non-English speakers group North and South America as a single unit, although this is not scientifically supported.

- Depending on the definition, Panama could be considered a transcontinental country while the ABC islands (Aruba, Bonaire, and Curaçao) and Trinidad and Tobago could be considered either parts of North America or South America.

- Since the Lucayan Archipelago is located in the Atlantic Ocean rather than Caribbean Sea, The Bahamas are part of the West Indies but are not technically part of the Caribbean, although the United Nations groups them with the Caribbean.

- Because of ongoing activity of the Soufriere Hills volcano beginning in July 1995, much of Plymouth was destroyed and government offices were relocated to Brades. Plymouth remains the de jure capital.

- Panama is generally considered a North American country, though some authorities divide it at the Panama Canal. Figures listed here are for the entire country.

- Since the Lucayan Archipelago is located in the Atlantic Ocean rather than Caribbean Sea, the Turks and Caicos Islands are part of the West Indies but are not technically part of the Caribbean, although the United Nations groups them with the Caribbean.

- Includes the states of Hawaii and Alaska which are both separated from the US mainland, with Hawaii distant from the North American landmass in the Pacific Ocean and therefore more commonly associated with the other territories of Oceania while Alaska is located between Asia (Russia) and Canada.

- The receding of oceans during successive ice ages may have enabled migrants to cross the land bridge as far back as 40,000 years.[83]

- While not conclusive, some South American rock painting has been dated to 25,000 years ago.[87]

- Descriptions of sites Erikson explored seem to correspond to Baffin Island, the Labrador coast near Cape Porcupine, as well as Belle Isle, and a site which led him to name the country Vinland ('Wineland').[95]

Citations

- "GDP PPP, current prices". International Monetary Fund. 2021. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 16 January 2022.

- "GDP Nominal, current prices". International Monetary Fund. 2021. Archived from the original on 25 February 2017. Retrieved 16 January 2022.

- "Nominal GDP per capita". International Monetary Fund. 2021. Archived from the original on 11 January 2020. Retrieved 16 January 2022.

- "Religious Composition by Country, 2010-2050". www.pewforum.org. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- "Demographia.com" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 August 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- pp. 30–31, Geography: Realms, Regions, and Concepts, H. J. de Blij and Peter O. Muller, Wiley, 12th ed., 2005 (ISBN 0-471-71786-X.)

- Lewis, Martin W.; Wigen, Karen E. (1997). "Chapter One, The Architecture of Continents". The Myth of Continents. University of California Press. p. 168. ISBN 0-520-20742-4.

- Burchfield, R. W., ed. 2004. "America." Fowler's Modern English Usage (ISBN 0-19-861021-1) New York: Oxford University Press, p. 48

- McArthur, Tom. 1992."North American." The Oxford Companion to the English Language (ISBN 0-19-214183-X) New York: Oxford University Press, p. 707.

- "Common Errors in English Usage". Prof Paul Brians, Washing State University. 16 May 2016. Archived from the original on 24 April 2022. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- "Amerigo Vespucci". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- Herbermann, Charles George, ed. (1907). The Cosmographiæ Introductio of Martin Waldseemüller in Facsimile. Translated by Edward Burke and Mario E. Cosenza, introduction by Joseph Fischer and Franz von Wieser. New York: The United States Catholic Historical Society. p. 9.

Latin: "Quarta pars per Americum Vesputium (ut in sequentibus audietur) inventa est, quam non video, cur quis jure vetet, ab Americo inventore sagacis ingenii viro Amerigen quasi Americi terram sive Americam dicendam, cum et Europa et Asia a mulieribus sua sortita sint nomina."

- Arbuckle, Alex (24 December 2016). "This 509-year-old map contains the first known use of the word 'America' — but not where you may think". Mashable. Archived from the original on 26 May 2022. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- Apianus, Petrus (1553), English: 1553 world map - Charta Cosmographica, Cum Ventorum Propria Natura et Operatione, retrieved 10 August 2022

- University, © Stanford; Stanford; California 94305. "Charta Cosmographica, Cum Ventorum Propria Natura et Operatione". Barry Lawrence Ruderman Map Collection - Spotlight at Stanford. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- Cohen, Jonathan. "The Naming of America: Fragments We've Shored Against Ourselves". Archived from the original on 15 August 2018. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- Lloyd, John; Mitchinson, John (2006). The Book of General Ignorance. Harmony Books. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-307-39491-0.

New countries or continents were never named after a person's first name, but always after the second ...

- Marcou, Jules (1890). "Amerriques, Ameriggo Vespucci, and America". Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution (PDF). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 647. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 January 2022. Retrieved 23 October 2021.

- Marcou, Jules (March 1875). "Origin of the Name America". The Atlantic Monthly: 291–295. Archived from the original on 28 January 2022. Retrieved 23 October 2021.

- "Mercator 1587 | Envisioning the World | The First Printed Maps". lib-dbserver.princeton.edu. Archived from the original on 12 September 2020. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- Division, United Nations Statistics. "UNSD — Methodology". unstats.un.org. Archived from the original on 30 August 2017. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

- Division, United Nations Statistics. "UNSD — Methodology". unstats.un.org. Archived from the original on 30 August 2017. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

- Division, United Nations Statistics. "UNSD — Methodology". unstats.un.org. Archived from the original on 30 August 2017. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

- "Norteamérica" [North America] (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 30 January 2009.

In Ibero-America, North America is considered a subcontinent containing Canada, the United States, Mexico, Greenland, Bermuda and Saint-Pierre and Miquelon.

- "Six or Seven Continents on Earth". Archived from the original on 26 November 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2016. "In Europe and other parts of the world, many students are taught of six continents, where North and South America are combined to form a single continent of America. Thus, these six continents are Africa, America, Antarctica, Asia, Australia, and Europe."

- "Continents". Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2016. "six-continent model (used mostly in France, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Romania, Greece, and Latin America) groups together North America+South America into the single continent America."

- "AMÉRIQUE" (in French). Archived from the original on 5 December 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- "America" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- "Acta Solemne de la Declaración de Independencia de la América Septentrional" [Solemn Act of the Declaration of Independence of Northern America]. Archivos de la Independencia (in Spanish). Archivo General de la Nación. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 8 July 2011.

- Office Québécois de la langue francaise. "Status of the French language". Government of Quebec. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- "Central America". Encarta Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 3 November 2009. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- "Caribbean". The Free Dictionary. Archived from the original on 6 November 2011. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- "The World Factbook – North America". Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 23 June 2011. Retrieved 20 June 2011.

- "Countries in North America – Country Reports". Country Reports. Archived from the original on 27 April 2015.

- "North America: World of Earth Science". eNotes Inc. Archived from the original on 20 December 2010. Retrieved 20 June 2011.

- "North American Region". The Trilateral Commission. Archived from the original on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- Parsons, Alan; Schaffer, Jonathan (May 2004). Geopolitics of oil and natural gas. Economic Perspectives. U.S. Department of State.

- "Definition of major areas and regions". United Nations. Archived from the original on 3 July 2019. Retrieved 3 October 2007.

- "Composition of macro geographical (continental) regions, geographical sub-regions, and selected economic and other groupings". UN Statistics Division. Archived from the original on 16 January 2019. Retrieved 3 October 2007. (French Archived 24 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine)

- "Chapter 5, Middle America". University of Minnesota. 17 June 2016. Archived from the original on 1 April 2018. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- "Middle America (region, Mesoamerica)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 19 September 2011. Retrieved 20 June 2011.

- "SPP Background". CommerceConnect.gov. Security and Prosperity Partnership of North America. Archived from the original on 18 June 2008. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- "Ecoregions of North America". United States Environmental Protection Agency. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- "What's the difference between North, Latin, Central, Middle, South, Spanish and Anglo America?". About.com. Archived from the original on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 25 January 2007.

- Unless otherwise noted, land area figures are taken from "Demographic Yearbook—Table 3: Population by sex, rate of population increase, surface area and density" (PDF). United Nations Statistics Division. 2008. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "World Population Prospects 2022". population.un.org. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- "World Population Prospects 2022: Demographic indicators by region, subregion and country, annually for 1950-2100" (XSLX). population.un.org ("Total Population, as of 1 July (thousands)"). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- Population estimates are taken from the Central Bureau of Statistics Netherlands Antilles. "Statistical information: Population". Government of the Netherlands Antilles. Archived from the original on 1 May 2010. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- These population estimates are for 2010, and are taken from "The World Factbook: 2010 edition". Government of the United States, Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 26 November 2015. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- Land area figures taken from "The World Factbook: 2010 edition". Government of the United States, Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 31 January 2014. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- "The Olympic symbols" (PDF). Lausanne: Olympic Museum and Studies Centre: International Olympic Committee. 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2008. The five rings of the Olympic flag represent the five inhabited, participating continents (Africa, America, Asia, Europe, and Oceania Archived 23 February 2002 at the Wayback Machine).

- Equipo (1997). "Continente". Océano Uno, Diccionario Enciclopédico y Atlas Mundial. pp. 392, 1730. ISBN 978-84-494-0188-6.

- Los Cinco Continentes (The Five Continents). Planeta-De Agostini Editions. 1997. ISBN 978-84-395-6054-8.

- "Encarta, "Norteamérica"" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 30 January 2009.

- "North America". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 20 May 2012. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- "Map And Details Of All 7 Continents". worldatlas.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

In some parts of the world, students are taught that there are only six continents, as they combine North America and South America into one continent called the Americas.

- Rosenberg, Matt (11 April 2020). "Ranking the 7 Continents by Size and Population". ThoughtCo. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- "North America Land Forms and Statistics". World Atlas.com. Archived from the original on 23 June 2013. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- "Americas". Standard Country and Area Codes Classifications (M49). United Nations Statistics Division. Archived from the original on 11 December 2009. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- "North America". Atlas of Canada. Archived from the original on 21 October 2006.

- "North America Atlas". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 25 May 2020. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- "Central America". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- Garcia-Castellanos, D.; Lombardo, U. (2007). "Poles of Inaccessibility: A Calculation Algorithm for the Remotest Places on Earth" (PDF). Scottish Geographical Journal. 123 (3): 227–233. doi:10.1080/14702540801897809. S2CID 55876083. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 June 2014.

- Dalziel, I.W.D. (1992). "On the organization of American Plates in the Neoproterozoic and the breakout of Laurentia". GSA Today. 2 (11): 237–241.

- Merali, Zeeya; Skinner, Brian J. (9 January 2009). Visualizing Earth Science. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-41847-5.

- "Land Bridge Linking Americas Rose Earlier Than Thought". LiveScience.com. 10 April 2015. Archived from the original on 4 October 2015. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- Dodson, Peter (1997). "American Dinosaurs". In Currie, Phillip J.; Padian, Kevin (eds.). Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. Academic Press. pp. 10–13.

- Weishampel, David B. (2004). Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Halszka, Osmólska (eds.). Dinosaur distribution (Late Jurassic, North America). The Dinosauria. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 543–545. ISBN 978-0-520-24209-8.

- Wallace, Stewart W. (1948). Geology Of Canada. The Encyclopedia of Canada. Vol. III. Toronto: University Associates of Canada. pp. 23–26. Archived from the original on 4 July 2010. Retrieved 1 June 2011 – via Marianopolis College.

{{cite book}}: External link in|via= - "Digging for Diamonds 24/7 Under Frozen Snap Lake". Wired. Archived from the original on 3 September 2011. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

- "3-D Magnetic Imaging using Conjugate Gradients: Temagami anomaly". Archived from the original on 11 July 2009. Retrieved 13 March 2008.

- University of Washington. "Cascades weather". University of Washington. Archived from the original on 10 March 2013. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- SF to do. "Temperature of San Francisco". tourism. Archived from the original on 19 July 2013.

- "Rainfall of NYC". Current Results. Archived from the original on 5 July 2015. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- Thompson, Andrea (18 May 2007). "Top 10 wettest cities". livescience. Archived from the original on 15 February 2015. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- Haberlin, Rita D. (2015). "Climates Regions of North America". Peralta Colleges, Physical Geography. Archived from the original on 2 October 2015.

- "Facts and Information about the Continent of North America". Natural History on the Net. 7 July 2016. Archived from the original on 15 September 2018. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- Curtin, Jeremiah (2014). Creation Myths of Primitive America. Jazzybee Verlag. p. 2. ISBN 978-3-8496-4454-3. Archived from the original on 9 February 2016. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- Krensky, Stephen (1987). Who Really Discovered America?. Illustrated by Steve Sullivan. Scholastic Inc. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-590-40854-7.