Maghreb

The Maghreb (/ˈmʌɡrəb/; Arabic: الْمَغْرِب, romanized: al-Maghrib, lit. 'the west'), also known as Northwest Africa,[2] is the western part of North Africa and the Arab world. The region includes Algeria, Libya, Mauritania (also considered part of West Africa), Morocco, and Tunisia. The Maghreb also includes the disputed territory of Western Sahara (controlled mostly by Morocco and partly by the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic) and the Spanish cities Ceuta and Melilla.[3] As of 2018, the region had a population of over 100 million people.

| Maghreb المغرب | |

|---|---|

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Countries and territories | |

| Major regional organizations | Arab League, Arab Maghreb Union, COMESA, Community of Sahel-Saharan States, Union for the Mediterranean |

| Population | 105,095,436 (2021*)[1] |

| Population density | 16.72/km2 |

| Area | 6,045,741 km2 (2,334,274 sq mi) |

| GDP PPP | $1.299 trillion (2020) |

| GDP PPP per capita | $12,628 (2020) |

| GDP nominal | $382.780 billion (2020) |

| GDP nominal per capita | $3,720 (2020) |

| Languages |

|

| Religion | Sunni Islam, Christianity and Judaism |

| Capitals |

|

| Currency |

|

Through the 18th and 19th centuries, English sources often referred to the region as the Barbary Coast or the Barbary States, a term derived from the demonym of the Berbers.[4][5] Sometimes, the region is referred to as the Land of the Atlas, referring to the Atlas Mountains, which are located within it.[6] In Berber languages, the word "Tamazgha" is used to refer to the Maghreb region plus the smaller parts of Mali, Niger, Egypt and the Spanish Canary Islands that have traditionally been inhabited by the Berbers.

The Maghreb is usually defined as encompassing much of the northern part of Africa, including a large portion of the Sahara Desert, but excluding Egypt and Sudan, which are considered to be located in the Mashriq — the eastern part of the Arab world. The traditional definition of the Maghreb — which restricted its scope to the Atlas Mountains and the coastal plains of Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia and Libya — was expanded in modern times to include Mauritania and the disputed territory of Western Sahara. During the era of Al-Andalus on the Iberian Peninsula (711–1492), the Maghreb's inhabitants — the Muslim Berbers, or Maghrebi — were known by Europeans as the "Moors".[7]

Before the establishment of modern nation states in the region during the 20th century, the Maghreb most commonly referred to a smaller area, between the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlas Mountains in the south. It often also included the territory of eastern Libya, but not modern Mauritania. As recently as the late 19th century, the term "Maghreb" was used to refer to the Western Mediterranean region of coastal North Africa in general, and to Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia, in particular.[8]

During the rule of the Berber kingdom of Numidia, the region was somewhat unified as an independent political entity. This period was followed by one of the Roman Empire's rule or influence. The Germanic Vandals invaded after that, followed by the equally brief re-establishment of a weak Roman rule by the Byzantine Empire. The Islamic Caliphates came to power under the Umayyad Caliphate, the Abbasid Caliphate and the Fatimid Caliphate. The most enduring rule was that of the local Berber empires of the Ifranid dynasty (also called Emirate of Tlemcen with abu Qurra as leader; the Berbers called him "caliph" Ibn Khaldun, as explained in his book Kitab al ibar), Almoravid dynasty, Almohad Caliphate, Hammadid dynasty, Zirid dynasty, Marinid dynasty, Zayyanid dynasty, Hafsid dynasty and Wattasid dynasty, extending from the 8th to 13th centuries. The Ottoman Empire for a period also controlled parts of the region.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, the region was ruled by European powers: France (Algeria, Tunisia, Mauritania and most of Morocco), Spain (northern Morocco and Western Sahara) and Italy (Libya). Italy was expelled from North Africa by the Allies in World War II. Decolonization of the region continued in the decades thereafter, with violent conflicts such as the Algerian War, the Ifni War and the Western Sahara War.

Algeria, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, and Tunisia established the Arab Maghreb Union in 1989 to promote cooperation and economic integration in a common market. It was envisioned initially by Muammar Gaddafi as a superstate. The union included Western Sahara implicitly under Morocco's membership,[9] and ended Morocco's long cold war with Algeria over this territory. However, this progress was short-lived, and the union is now dormant.

Tensions between Algeria and Morocco over Western Sahara re-emerged, reinforced by the unsolved border dispute between the two countries. These two main conflicts have hindered progress on the union's joint goals and practically made it inactive as a whole.[10] The instability in the region and growing cross-border security threats revived calls for regional cooperation. In May 2015 foreign ministers of the Arab Maghreb Union declared a need for coordinated security policy at the 33rd session of the follow-up committee meeting; this revived hope of some form of cooperation.[11]

Terminology

The toponym maghrib is a geographical term that the Muslim Arabs gave to the region extending from Alexandria in the east to the Atlantic Ocean in the west. Etymologically it means both the western place/land and the place where the sun sets. It is composed of the prefix ma−, which makes a noun out of the verb root, and غرب (gharaba, to set, as in setting sun) (from gh-r-b root (غ-ر-ب)).

Muslim historians and geographers divided the region into three areas: al-Maghrib al-Adna (the near Maghrib), which included the lands extending from Alexandria to Tarabulus (modern-day Tripoli) in the west; al-Maghrib al-Awsat (the middle Maghrib), which extended from Tripoli to Bijaya (Béjaïa); and al-Maghrib al-Aqsa (the far Maghrib), which extended from Tahart (Tiaret) to the Atlantic Ocean.[12] They disagreed, however, over the definition of the eastern boundary. Some authors place it at the sea of Kulzum (the Red Sea) and thus include Egypt and the country of Barca in the Maghrib. Ibn Khaldun does not accept this definition because, he says, the inhabitants of the Maghreb do not consider Egypt and Barca as forming part of Maghrib. The latter commences only at the province of Tripoli and includes the districts of which the country of the Berbers was composed in former times. Later Maghribi writers repeated the definition of Ibn Khaldun, with a few variations in details.[13]

As of 2017 the term Maghrib is still used in opposition to Mashriq in a sense near to that which it had in medieval times, but it also denotes simply Morocco when the full al-Maghrib al-Aksa is abbreviated. Certain politicians seek a political union of the North African countries, which they call al-Maghrib al-Kabir (the grand Maghrib) or al-Maghrib al-Arabi (the Arab Maghrib).[13][14]

Speakers of Berber languages call this region Tamazɣa or Tamazgha, which translates to "land of the Berbers".[15][16] Since the second half of the twentieth century, this term has been popularized by activists promoting Berberism.

History

.jpg.webp)

Prehistory

Around 3,500 BC, changes in the tilt of the Earth's orbit appear to have caused a rapid desertification of the Sahara region[17] forming a natural barrier that severely limited contact between the Maghreb and sub-Saharan Africa. The Berber people have inhabited western North Africa since at least 10,000 BC.[18]

Antiquity

Partially isolated from the rest of the continent by the Atlas Mountains (stretching from present-day Morocco to present-day Tunisia) and by the Sahara desert, inhabitants of the northern parts of the Berber world have long had commercial and cultural ties across the Mediterranean Sea to the inhabitants of the regions of Southern Europe and Western Asia. These trade relations date back at least to the Phoenicians in the 1st millennium BC. (According to tradition, the Phoenicians founded their colony of Carthage (in present-day Tunisia) c. 800 BC).

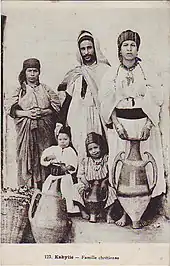

Phoenicians and Carthaginians arrived for trade. The main Berber and Phoenician settlements centered in the Gulf of Tunis (Carthage, Utica, Tunisia) along the North African littoral, between the Pillars of Hercules and the Libyan coast east of ancient Cyrenaica. They dominated the trade and intercourse of the Western Mediterranean for centuries. Rome's defeat of Carthage in the Punic Wars (264 to 146 BC) enabled Rome to establish the Province of Africa (146 BC) and to control many of these ports. Rome eventually took control of the entire Maghreb north of the Atlas Mountains. Rome was greatly helped by the defection of Massinissa (later King of Numidia, r. 202 – 148 BC) and of Carthage's eastern Numidian Massylii client-allies. Some of the most mountainous regions, such as the Moroccan Rif, remained outside Roman control. Furthermore, during the rule of the Romans, Byzantines, Vandals and Carthaginians the Kabyle people were the only or one of the few in North Africa who remained independent.[19][20][21][22] The Kabyle people were incredibly resistible so much so that even during the Arab conquest of North Africa they still had control and possession over their mountains.[23][24]

The pressure put on the Western Roman Empire by the Barbarian invasions (notably by the Vandals and Visigoths in Iberia) in the 5th century AD reduced Roman control and led to the establishment of the Vandal Kingdom of North Africa in 430 A.D., with its capital at Carthage. A century later, the Byzantine emperor Justinian I sent (533) a force under General Belisarius that succeeded in destroying the Vandal Kingdom in 534. Byzantine rule lasted for 150 years. The Berbers contested the extent of Byzantine control.[25]

After the advent of Islam in Mediterranean Africa in the period from 639 to 700 AD, Arabs took control of the entire Maghreb region.

Middle Ages

The Arabs reached the Maghreb in early Umayyad times. Islamic Berber kingdoms such as the Almohads expansion and the spread of Islam contributed to the development of trans-Saharan trade. While restricted due to the cost and dangers, the trade was highly profitable. Commodities traded included such goods as salt, gold, ivory, and slaves. Arab control over the Maghreb was quite weak. Various Islamic variations, such as the Ibadis and the Shia, were adopted by some Berbers, often leading to scorning of Caliphal control in favour of their own interpretation of Islam.

As a result of the invasion of the Banu Hilal Arabs, the Arabic language and dialects spread slowly without eliminating Berber. These Arabs had been set upon the Berbers by the Fatimids in punishment for their Zirid former Berber clients who defected and abandoned Shiism in the 12th century. Throughout this period, the Berber world most often was divided into three states, roughly corresponding to modern Morocco, western Algeria, and eastern Algeria and Tunisia. The Maghreb region was occasionally briefly unified, as under the Almohad Berber empire, Fatimids and briefly under the Zirids. The Hammadids also managed to conquer land in all countries in the Maghreb region. [27][28][29]

Early modern history

Modern history

After the 19th century, areas of the Maghreb were colonized by France, Spain and later Italy.

Today, more than two and a half million Maghrebi immigrants live in France, many from Algeria and Morocco. In addition, as of 1999 there were 3 million French of Maghrebi origin (defined as having at least one grandparent from Algeria, Morocco or Tunisia).[30] A 2003 estimate suggests six million French residents were ethnic Maghrebi.[31]

Population

_(14580573400).jpg.webp)

The Maghreb is primarily inhabited by peoples of Berber ancestral origin. Berbers are autochthonous to Algeria (80%), Libya (>60%), Morocco (80%), and Tunisia (>88%).[32] Ethnic French, Arab, West African, and Sephardic Jewish populations also inhabit the region.

Various other influences are also prominent throughout the Maghreb. In northern coastal towns, in particular, several waves of European immigrants influenced the population in the Medieval era. Most notable were the moriscos and muladies, that is, the indigenous Spaniards (Moors) who were forcibly converted to Catholicism and later expelled, together with ethnic Arab and Berber Muslims, during the Spanish Catholic Reconquista. Other European contributions included French, Italian, and English crews and passengers taken captive by corsairs. In some cases, they were returned to families after being ransomed; in others, they were used as slaves or assimilated and adopted into tribes.[33]

Historically, the Maghreb was home to significant historic Jewish communities called Maghrebim, who predated the 7th-century introduction and conversion of the region to Islam. These were later augmented by Sephardic Jews from Spain and Portugal who, fleeing the Spanish Catholic Inquisition of the 15th and 16th centuries, established a presence in North Africa. They settled primarily in the urban trading centers.

Another significant group is Turks, who migrated with the expansion of the Ottoman Empire.

Africans from south of the Sahara joined the population mix during centuries of trans-Saharan trade. Traders and slaves went to the Maghreb from the Sahel region. On the Saharan southern edge of the Maghreb are small communities of black populations, sometimes called Haratine.

In Algeria especially, a large European minority, known as the "pied noirs", immigrated to the region, settling under French colonial rule in the late 19th century. They established farms and businesses. The overwhelming majority of these, however, left Algeria during and following the war for independence.[34]

In comparison to the population of France, the Maghrebi population was one-eighth of France's population in 1800, one-quarter in 1900, and equal in 2000. The Maghreb is home to 1% of the global population as of 2010.[35]

Genetics

The Y-chromosome genetic structure of the Maghreb population seems to be modulated chiefly by geography. The Y-DNA Haplogroups E1b1b and J make up the vast majority of the genetic markers of the populations of the Maghreb. Haplogroup E1b1b is the most widespread among Maghrebi groups, especially the downstream lineage of E1b1b1b1a, which is typical of the indigenous Berbers of North-West Africa. Haplogroup J is more indicative of Middle East origins, and has its highest distribution among populations in Arabia and the Levant. Due to the distribution of E-M81(E1b1b1b1a), which has reached its highest documented levels in the world at 95–100% in some populations of the Maghreb, it has often been termed the "Berber marker" in the scientific literature. The second most common marker, Haplogroup J, especially J1,[36][37] which is typically Middle Eastern and originates in the Arabian peninsula, can reach frequencies of up to 35% in the region.[38][39] Its highest density is found in the Arabian Peninsula.[39] Haplogroup R1,[40] a Eurasian marker, has also been observed in the Maghreb, though with lower frequency. The Y-DNA haplogroups shown above are observed in both Arabic speakers and Berber-speakers.

The Maghreb Y chromosome pool (including both Arab and Berber populations) may be summarized for most of the populations as follows, where only two haplogroups E1b1b and J comprise generally more than 80% of the total chromosomes:[41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48]

| Haplogroup | Marker | Sahara/Mauritania | Morocco | Algeria | Tunisia | Libya |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 189 | 760 | 156 | 601 | – | |

| A | – | 0.26 | – | – | – | |

| B | 0.53 | 0.66 | – | 0.17 | – | |

| C | – | – | – | – | – | |

| DE | – | – | – | – | – | |

| E1a | M33 | 5.29 | 2.76 | 0.64 | 0.5 | – |

| E1b1a | M2 | 6.88 | 3.29 | 5.13 | 0.67 | – |

| E1b1b1 | M35 | – | 4.21 | 0.64 | 1.66 | – |

| E1b1b1a | M78 | – | 0.79 | 1.92 | – | – |

| E1b1b1a1 | V12 | – | 0.26 | 0.64 | – | – |

| E1b1b1a1b | V32 | – | – | – | – | – |

| E1b1b1a2 | V13 | – | 0.26 | 0.64 | – | – |

| E1b1b1a3 | V22 | – | 1.84 | 1.28 | 3 | – |

| E1b1b1a4 | V65 | – | 3.68 | 1.92 | 3.16 | – |

| E1b1b1b | M81 | 65.56 | 67.37 | 64.23 | 72.73 | – |

| E1b1b1c | M34 | 11.11 | 0.66 | 1.28 | 1.16 | – |

| F | M89 | – | 0.26 | 3.85 | 2.66 | – |

| G | M201 | – | 0.66 | – | 0.17 | – |

| H | M69 | – | – | – | – | – |

| I | – | 0.13 | – | 0.17 | – | |

| J1 | 3.23 | 6.32 | 1.79 | 6.64 | – | |

| J2 | – | 1.32 | 4.49 | 2.83 | – | |

| K | – | 0.53 | 0.64 | 0.33 | – | |

| L | – | – | – | – | – | |

| N | – | – | – | – | – | |

| O | – | – | – | – | – | |

| P, R | – | 0.26 | – | 0.33 | – | |

| Q | – | – | 0.64 | – | – | |

| R1a1 | – | – | 0.64 | 0.5 | – | |

| R1b | M343 | – | – | – | – | – |

| R1b1a | V88 | 6.88 | 0.92 | 2.56 | 1.83 | – |

| R1b1b | M269 | 0.53 | 3.55 | 7.04 | 0.33 | – |

| R2 | – | – | – | – | – | |

| T | M70 | – | – | – | 1.16 | – |

Religion

The original religions of the peoples of the Maghreb seem[49] to have been based in and related to fertility cults of a strong matriarchal pantheon. This theory is based on the social and linguistic structures of the Amazigh cultures that antedated all Egyptian and eastern Asian, northern Mediterranean, and European influences.

Historic records of religion in the Maghreb region show its gradual inclusion in the Classical World, with coastal colonies established first by Phoenicians, some Greeks, and later extensive conquest and colonization by the Romans. By the 2nd century of the common era, the area had become a center of Phoenician-speaking Christianity. Its bishops spoke and wrote in Punic, and Emperor Septimius Severus was noted by his local accent. Roman settlers and Romanized populations converted to Christianity. The region produced figures such as Christian church writer Tertullian (c. 155 – c. 202); and Christian martyrs or leading figures such as Perpetua, and Felicity (martyrs, c. 200 CE); St. Cyprian of Carthage (+ 258); St. Monica; her son the philosopher St. Augustine, Bishop of Hippo I (+ 430) (1); and St. Julia of Carthage (5th century).

Islam

Islam arrived in 647 and challenged the domination of Christianity. The first permanent foothold of Islam was the founding in 667 of the city of Kairouan, in present-day Tunisia. Carthage fell to Muslims in 698 and the remainder of the region fell by 709. Islamization proceeded slowly.

From the end of the 7th century, over a period of more than 400 years, the region's peoples converted to Islam. Many left during this time for Italy, although surviving letters showed correspondence from regional Christians to Rome up until the 12th century. Christianity was still a living faith. Although there were numerous conversions after the conquest, Muslims did not become a majority until some time late in the 9th century. During the 10th century, Islam became by far the dominant religion in the region.[50] Christian bishoprics and dioceses continued to be active and continued their relations with the Christian Church of Rome. As late as the reign of Pope Benedict VII (974–983), a new Archbishop of Carthage was consecrated. From the 10th century, Christianity declined in the region.[51] By the end of the 11th century, only two bishops were left in Carthage and Hippo Regius. Pope Gregory VII (1073–85) consecrated a new bishop for Hippo. Christianity seems to have suffered several shocks that led to its demise. First, many upper-class, urban-dwelling, Latin-speaking Christians left for Europe after the Muslim conquest. The second major influence was the large-scale conversions to Islam from the end of the 9th century. Many Christians of a much reduced community departed in the mid-11th century, and remnants were evacuated in the 12th by the Norman rulers of Sicily. The Latin-African language lingered a while longer.

There was a small but thriving Jewish community, as well as a small Christian community. Most Muslims follow the Sunni Maliki school. Small Ibadi communities remain in some areas. A strong tradition of venerating marabouts and saints' tombs is found throughout regions inhabited by Berbers. This practice was also common among the Jews of the region. Any map of the region demonstrates the tradition by the proliferation of "Sidi"s, showing places named after the marabouts. This tradition has declined through the 20th century. A network of zaouias traditionally helped teach basic literacy and knowledge of Islam in rural regions.

Christianity

Communities of Christians, mostly Catholics and Protestant, persist in Algeria (100,000–380,000),[52] Mauritania (10,000),[53] Morocco (~380,000),[54] Libya (170,000), and Tunisia (100,750).[55] Most of the Roman Catholics in Greater Maghreb are of French, Spanish, and Italian descent, with ancestors who immigrated during the colonial era. Some are foreign missionaries or immigrant workers. There are also Christian communities of Berber or Arab descent in Greater Maghreb, made up of persons who converted mostly during the modern era, or under and after French colonialism.[56][57] Prior to independence, Algeria was home to 1.4 million pieds-noirs (ethnic French who were mostly Catholic),[58] and Morocco was home to half a million Europeans,[59] Tunisia was home to 255,000 Europeans,[60] and Libya was home to 145,000 Europeans. In religion, most of the pieds-noirs in Maghreb are Catholic. Due to the exodus of the pieds-noirs in the 1960s, more North African Christians of Berber or Arab descent now live in France than in Greater Maghreb.

Recently, the Protestant community of Berber or Arab descent has grown significantly as additional individuals convert to Christianity, especially to Evangelicalism. This has occurred in Algeria,[61] especially in the Kabylie,[62] Morocco[63] and in Tunisia.[64]

A 2015 study estimates 380,000 Muslims converted to Christianity in Algeria.[65] The number of Moroccans who converted to Christianity (most of them secret worshipers) are estimated between 40,000[66]-150,000.[67][68] The International Religious Freedom Report for 2007 estimates thousands of Tunisian Muslims have converted to Christianity.[64] A 2015 study estimate some 1,500 believers in Christ from a Muslim background living in Libya.[69]

Maghrebi traders in Jewish history

In the 10th century, as the social and political environment in Baghdad became increasingly hostile to Jews, some Jewish traders emigrated to the Maghreb, especially Kairouan, Tunisia. Over the following two or three centuries, such Jewish traders became known as the Maghribi, a distinctive social group who traveled throughout the Mediterranean world. They passed this identification on from father to son. Their tight-knit pan-Maghreb community had the ability to use social sanctions as a credible alternative to legal recourse, which was weak at the time anyway. This unique institutional alternative permitted the Maghribis to very successfully participate in the Mediterranean trade.[70]

Geography

Ecoregions

The Maghreb is divided into a Mediterranean climate region in the north, and the arid Sahara in the south. The Maghreb's variations in elevation, rainfall, temperature, and soils give rise to distinct communities of plants and animals. The World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) identifies several distinct ecoregions in the Maghreb.

Mediterranean Maghreb

The portions of the Maghreb between the Atlas Mountains and the Mediterranean Sea, along with coastal Tripolitania and Cyrenaica in Libya, are home to Mediterranean forests, woodlands, and scrub. These ecoregions share many species of plants and animals with other portions of Mediterranean Basin. The southern extent of the Mediterranean Maghreb corresponds with the 100 mm (3.9 in) isohyet, or the southern range of the European Olive (Olea europea)[71] and Esparto Grass (Stipa tenacissima).[72]

- Mediterranean acacia-argania dry woodlands and succulent thickets (Morocco, Canary Islands (Spain), Western Sahara)

- Mediterranean dry woodlands and steppe (Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, Tunisia)

- Mediterranean woodlands and forests (Algeria, Libya, Morocco, Tunisia)

- Mediterranean conifer and mixed forests (Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia, Spain)

- Mediterranean High Atlas juniper steppe (Morocco)

Saharan Maghreb

The Sahara extends across northern Africa from the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea. Its central part is hyper-arid and supports little plant or animal life, but the northern portion of the desert receives occasional winter rains, while the strip along the Atlantic coast receives moisture from marine fog, which nourishes a greater variety of plants and animals. The northern edge of the Sahara corresponds to the 100 mm isohyet, which is also the northern range of the date palm (Phoenix dactylifera).[72]

- North Saharan steppe and woodlands: This ecoregion lies along the northern edge of the Sahara, next to the Mediterranean forests, woodlands, and scrub ecoregions of the Mediterranean Maghreb and Cyrenaica. Winter rains sustain shrublands and dry woodlands that form a transition between the Mediterranean climate regions to the north and the hyper-arid Sahara proper to the south. It covers 1,675,300 square km (646,800 square miles) in Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, Tunisia, and Western Sahara.[73]

- Atlantic coastal desert: The Atlantic coastal desert occupies a narrow strip along the Atlantic coast, where fog generated offshore by the cool Canary Current provides sufficient moisture to sustain a variety of lichens, succulents, and shrubs. It covers 39,900 square kilometres (15,400 sq mi) in Western Sahara and Mauritania.[74]

- Sahara desert: This ecoregion covers the hyper-arid central portion of the Sahara where rainfall is minimal and sporadic. Vegetation is rare, and this ecoregion consists mostly of sand dunes (erg), stone plateaus (hamada), gravel plains (reg), dry valleys (wadi), and salt flats. It covers 4,639,900 square km (1,791,500 square miles) of Algeria, Chad, Egypt, Libya, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, and Sudan.[75]

- Saharan halophytics: Seasonally flooded saline depressions in the Maghreb are home to halophytic, or salt-adapted, plant communities. The Saharan halophytics cover 54,000 square km (20,800 square miles), including Tunisian salt lakes of central Tunisia, Chott Melghir in Algeria, and other areas of Egypt, Algeria, Mauritania, and Western Sahara.[76]

Culture

The countries of the Maghreb share many cultural traditions. Among these is a culinary tradition that Habib Bourguiba defined as Western Arab, where bread or couscous are the staple foods, as opposed to Eastern Arab, where bread, crushed wheat or white rice are the staple foods. In terms of food, some similarities beyond the starches are found throughout the Arab world.

Among other cultural and artistic traditions, jewellery of the Berber cultures worn by Amazigh women and made of silver, beads and other applications was a common trait of Berber identities in large areas of the Maghreb up to the second half of the 20th century.[77]

Economy

Maghreb countries by GDP (PPP)

| List by the International Monetary Fund (2013) | List by the World Bank (2013) | List by the CIA World Factbook (2013) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

| List by the International Monetary Fund (2019) | List by the World Bank (2017) | List by the CIA World Factbook (2017) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

Medieval regions

- Ifriqiya (currently Tunisia, Constantinois and Tripolitania)

- Djerid

- Sous

- M'zab

- Draa Valley

- Hodna

- Rif

- Tamesna

- Tripolitania

- Maghreb al-Awsat (Central Maghreb – currently Northern Algeria)

- Maghreb al-Aqsa (Western Maghreb – currently Morocco)

- Maghreb al-Adna (Eastern Maghreb – currently Libya and Tunisia)

See also

- Arab Maghreb Union

- Barbary Coast

- Berber people

- History of Algeria

- History of Libya

- History of Mauritania

- History of Morocco

- History of Tunisia

- History of Western Sahara

- Maghreb French

- Maghreb toponymy

- Maghrebi script

- Maghrebi Arabs

- Maghrebi Jews

- Mashriq, "place of sunrise", which contrasts Maghreb, "place of sunset"

- Miloud

- Moors

- Occident

- Mughrabi (disambiguation)

- Plazas de soberanía

- Tamazgha

- Sahel

- Juliette Bessis, Maghreb scholar

Notes and references

- "COUNTRY COMPARISON :: POPULATION". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- English for Students: Northwest Africa english-for-students.com

- Article 143. Cortes Generales (Spanish Parliament) (1978). "Título VIII. De la Organización Territorial del Estado". Spanish Constitution of 1978. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- "Barbary Wars, 1801–1805 and 1815–1816". Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- "Antique Maps of North Africa". Archived from the original on 11 October 2008. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- Amin, Samir (1970). The Maghreb in the modern world: Algeria, Tunisia, Morocco. Penguin. p. 10. ISBN 9780140410297. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- "The Moors were simply Maghrebis, inhabitants of the Maghreb, the western part of the Islamic world, that extends from Spain to Tunisia, and represents a homogeneous cultural entity", Titus Burckhardt, Moorish Culture in Spain. Suhail Academy. 1997, p.7

- Elisée Reclus, Africa, edited by A. H. Keane, B. A., Vol. II, North-West Africa, Appleton and company, 1880, New York, p.95

- "L'Union du Maghreb arabe". Archived from the original on 20 April 2010. Retrieved 17 May 2010.

- "Maghreb". The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2001–05. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 11 July 2007.

- "Maghreb Countries Urged to Devise Common Security Strategy, Integration Project Remains Deadlocked", North Africa Post (2015)

- Idris El Hareir; Ravane Mbaye (2011). The Spread of Islam Throughout the World. UNESCO. pp. 375–376. ISBN 978-92-3-104153-2.

- Jan-Olaf Blichfeldt (1985). Early Mahdism: Politics and Religion in the Formative Period of Islam. Brill Archive. pp. 1183–1184. ISBN 9789004078376. GGKEY:T7DEYT42F5R.

- Hassan Sayed Suliman (1987). The Nationalist Movements in the Maghrib: A Comparative Approach. Scandinavian Institute of African Studies. p. 8. ISBN 978-91-7106-266-6.

- "Tamazgha, North African Berbers". Retrieved 9 February 2010.

- McDougall, James (31 July 2006). History and the culture of nationalism in Algeria (Page: 189). ISBN 978-0-521-84373-7. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- Sahara's Abrupt Desertification Started by Changes in Earth's Orbit, Accelerated by Atmospheric and Vegetation Feedbacks, Science Daily. "One of the most striking climate changes of the past 11,000 years caused the abrupt desertification of the Saharan and Arabia regions midway through that period. The resulting loss of the Sahara to agricultural pursuits may be an important reason that civilizations were founded along the valleys of the Nile, the Tigris, and the Euphrates. German scientists, employing a new climate system model, have concluded that this desertification was initiated by subtle changes in the Earth's orbit and strongly amplified by resulting atmospheric and vegetation feedbacks in the subtropics."

- Historical Dictionary of the Berbers (Imazighen), by Hsain Ilahiane, (2006), p. 112. Quote: "The Siwan people are mostly Berbers, the indigenous people who once roamed the North African coast between Tunisia and Morocco. They inhabited the area as early as 10,000 B.C., first moving toward the coast but later inland as conquering powers pushed them to take refuge in the desert."

- The Middle East and North Africa 2003. Psychology Press. ISBN 9781857431322 – via Google Books.

- Walmsley, Hugh Mulleneux (10 April 1858). "Sketches of Algeria During the Kabyle War". Chapman and Hall – via Google Books.

- Wysner, Glora M. (30 January 2013). The Kabyle People. Read Books Ltd. ISBN 9781447483526 – via Google Books.

- The Encyclopedia Americana. Grolier. 10 April 1990. ISBN 9780717201211 – via Google Books.

- "The art journal London". Virtue. 10 April 1865 – via Google Books.

- Field, Henry Martyn (10 April 1893). "The Barbary Coast". C. Scribner's Sons – via Google Books.

- Stapleton, Timothy J. (2013). "North Africa to ca. 1870". A Military History of Africa. Vol. 1: The Precolonial Period: From Ancient Egypt to the Zulu Kingdom (Earliest Times to ca. 1870). Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 17-18. ISBN 9780313395703. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- Burckhardt, Titus (24 July 2009). Art of Islam: Language and Meaning. World Wisdom, Inc. ISBN 9781933316659 – via Google Books.

- Baadj, Amar S. (11 August 2015). Saladin, the Almohads and the Banū Ghāniya: The Contest for North Africa (12th and 13th centuries). BRILL. ISBN 9789004298576 – via Google Books.

- Hattstein, Markus; Delius, Peter (2004). Islam: Art and Architecture: Pg 614. ISBN 9783833111785.

- Ilahiane, Hsain (17 July 2006). Historical Dictionary of the Berbers (Imazighen). Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810864900 – via Google Books.

- "An Estimation of the Foreign-Origin Populations of France, Michèle Tribalat".

- "Estimé à six millions d'individus, l'histoire de leur enracinement, processus toujours en devenir, suscite la mise en avant de nombreuses problématiques...", « Être Maghrébins en France » in Les Cahiers de l’Orient, n° 71, troisième trimestre 2003

- Tej K. Bhatia, William C. Ritchie (2006). The Handbook of Bilingualism. John Wiley & Sons. p. 860. ISBN 978-0631227359. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - Davis, Robert. "British Slaves on the Barbary Coast". BBC. Retrieved 5 November 2009.

- "France and Maghreb – An enhanced partnership with the Maghreb (March 20, 2007)". French Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs. Retrieved 11 July 2007.

- Brunel, Claire, Maghreb regional and global integration: a dream to be fulfilled, Peterson Institute, 2008, p.1

- combined (Semino et al. 2004 30%) & (Arredi et al. 2004 32%)

- Semino, Ornella; Magri, Chiara; Benuzzi, Giorgia; Lin, Alice A; Al-Zahery, Nadia; Battaglia, Vincenza; MacCioni, Liliana; Triantaphyllidis, Costas; Shen, Peidong; Oefner, Peter J; Zhivotovsky, Lev A; King, Roy; Torroni, Antonio; Cavalli-Sforza, L. Luca; Underhill, Peter A; Santachiara-Benerecetti, A. Silvana (May 2004). "Origin, Diffusion, and Differentiation of Y-Chromosome Haplogroups E and J: Inferences on the Neolithization of Europe and Later Migratory Events in the Mediterranean Area". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 74 (5): 1023–1034. doi:10.1086/386295. PMC 1181965. PMID 15069642.

- Alshamali F, Pereira L, Budowle B, Poloni ES, Currat M (2009). "Local population structure in Arabian Peninsula revealed by Y-STR diversity". Hum. Hered. 68 (1): 45–54. doi:10.1159/000210448. PMID 19339785.

-

- Alshamali et al. 2009 81% (84/104) *Malouf et al. 2008: 70% (28/40) *Cadenas et al. 2008:45/62 = 72.6% J1-M267

- Robino, C; Crobu, F; Di Gaetano, C; Bekada, A; Benhamamouch, S; Cerutti, N; Piazza, A; Inturri, S; Torre, C (2008). "Analysis of Y-chromosomal SNP haplogroups and STR haplotypes in an Algerian population sample". International Journal of Legal Medicine. 122 (3): 251–5. doi:10.1007/s00414-007-0203-5. PMID 17909833. S2CID 11556974.

- Bosch E, Calafell F, Comas D, et al. (April 2001). "High-Resolution Analysis of Human Y-Chromosome Variation Shows a Sharp Discontinuity and Limited Gene Flow between Northwestern Africa and the Iberian Peninsula". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 68 (4): 1019–29. doi:10.1086/319521. ISSN 0002-9297. PMC 1275654. PMID 11254456.

- Nebel A, Landau-Tasseron E, Filon D, et al. (June 2002). "Genetic Evidence for the Expansion of Arabian Tribes into the Southern Levant and North Africa". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 70 (6): 1594–6. doi:10.1086/340669. ISSN 0002-9297. PMC 379148. PMID 11992266.

- Semino O, Magri C, Benuzzi G, et al. (May 2004). "Origin, Diffusion, and Differentiation of Y-Chromosome Haplogroups E and J: Inferences on the Neolithization of Europe and Later Migratory Events in the Mediterranean Area". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 74 (5): 1023–34. doi:10.1086/386295. ISSN 0002-9297. PMC 1181965. PMID 15069642.

- Arredi B, Poloni ES, Paracchini S, et al. (August 2004). "A Predominantly Neolithic Origin for Y-Chromosomal DNA Variation in North Africa". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 75 (2): 338–345. doi:10.1086/423147. ISSN 0002-9297. PMC 1216069. PMID 15202071.

- Cruciani F, La Fratta R, Santolamazza P, et al. (May 2004). "Phylogeographic Analysis of Haplogroup E3b (E-M215) Y Chromosomes Reveals Multiple Migratory Events Within and Out Of Africa". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 74 (5): 1014–22. doi:10.1086/386294. ISSN 0002-9297. PMC 1181964. PMID 15042509.

- Robino C, Crobu F, Di Gaetano C, et al. (May 2008). "Analysis of Y-chromosomal SNP haplogroups and STR haplotypes in an Algerian population sample". International Journal of Legal Medicine. 122 (3): 251–5. doi:10.1007/s00414-007-0203-5. ISSN 0937-9827. PMID 17909833. S2CID 11556974.

- Onofri V, Alessandrini F, Turchi C, et al. (August 2008). "Y-chromosome markers distribution in Northern Africa: High-resolution SNP and STR analysis in Tunisia and Morocco populations". Forensic Science International: Genetics Supplement Series. 1 (1): 235–6. doi:10.1016/j.fsigss.2007.10.173.

- Bekada A, Fregel R, Cabrera VM, Larruga JM, Pestano J, et al. (2013) Introducing the Algerian Mitochondrial DNA and Y-Chromosome Profiles into the North African Landscape. PLoS ONE 8(2): e56775. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0056775

- "The central position of women in the life of the Berbers of Northern-Africa exemplified by the Kabyles". www.second-congress-matriarchal-studies.com.

- Staying Roman, Jonathan Conant, pp. 362–368, 2012

- Insoll, T. (2003) "The Archaeology of Islam in Sub-Saharan Africa", Cambridge World Archaeology, http://content.schweitzer-ne.de/static/content/catalog/newbooks/978/052/165/9780521651714/9780521651714_Excerpt_001.pdf%5B%5D

- Deeb, Mary Jane. "Religious minorities", Algeria (Country Study). Federal Research Division, Library of Congress; ed., Helen Chapin Metz, December 1993. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- "Mauritania - Open Doors USA - Open Doors USA". www.opendoorsusa.org.

- "Africa :: Morocco — The World Factbook - Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. 9 November 2021.

- Fr Andrew Phillips. "The Last Christians Of North-West Africa: Some Lessons For Orthodox Today". Orthodoxengland.org.uk. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- Fahlbusch, Erwin; Bromiley, Geoffrey William; Lochman, Jan Milie; Mbiti, John; Pelikan, Jaroslav; Barrett, David B.; Vischer, Lukas (24 July 1999). The Encyclopedia of Christianity. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 9780802824158 – via Google Books.

- "Rising numbers of Christians in Islamic countries could pose threat to social order". World Review.

- Cook, Bernard A. (2001). Europe since 1945: an encyclopedia. New York: Garland. pp. 398. ISBN 978-0-8153-4057-7.

- De Azevedo, Raimondo Cagiano (1994) Migration and development co-operation.. Council of Europe. p. 25. ISBN 92-871-2611-9.

- Angus Maddison (20 September 2007). Contours of the World Economy 1–2030 AD:Essays in Macro-Economic History: Essays in Macro-Economic History. OUP Oxford. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-19-922721-1. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

-

- (in French) Sadek Lekdja, Christianity in Kabylie, Radio France Internationale, 7 mai 2001 Archived 18 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- Lucien Oulahbib, Le monde arabe existe-t-il ?, page 12, 2005, Editions de Paris, Paris.

- Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld | Morocco: General situation of Muslims who converted to Christianity, and specifically those who converted to Catholicism; their treatment by Islamists and the authorities, including state protection (2008-2011)". Refworld.

- "International Religious Freedom Report 2007": Tunisia. United States Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (14 September 2007). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Miller, Duane A. "Believers in Christ from a Muslim Background: A Global Census" – via www.academia.edu.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "'House-Churches' and Silent Masses —The Converted Christians of Morocco Are Praying in Secret". www.vice.com.

- Morocco: No more hiding for Christians, Evangelical Focus

- Osservatorio Internazionale: "La tentazione di Cristo" Archived 27 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine April 2010

- Johnstone, Patrick; Miller, Duane Alexander (2015). "Believers in Christ from a Muslim Background: A Global Census". IJRR. 11 (10): 1–19. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- Avner Greif (June 1993). "Contract Enforceability and Economic Institutions in Early Trade: The Maghribi Traders' Coalition" (PDF). American Economic Association in its journal American Economic Review. Retrieved 11 July 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help). See also Greif's "Reputation and Coalitions in Medieval Trade: Evidence on the Maghribi Traders", in Journal of Economic History Vol. XLIX, No. 4 (Dec. 1989) pp.857–882 - Dallman, Peter R. (1998) Plant Life in the World's Mediterranean Climates. California Native Plant Society/University of California Press, Berkeley. ISBN 0-520-20809-9

- Wickens, Gerald E. (1998) Ecophysiology of Economic Plants in Arid and Semi-Arid Lands. Springer, Berlin. ISBN 978-3-540-52171-6

- "North Saharan steppe and woodlands". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 31 December 2007.

- "Atlantic coastal desert". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 31 December 2007.

- "Sahara desert". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 31 December 2007.

- "Saharan halophytics". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 31 December 2007.

- See, for example, Rabaté, Marie-Rose (2015). Les bijoux du Maroc: du Haut-Atlas à la vallée du Draa. Paris: ACR ed. and Rabaté, Marie-Rose; Jacques Rabaté; Dominique Champault (1996). Bijoux du Maroc: du Haut Atlas à la vallée du Draa. Aix-en-Provence: Edisud/Le Fennec, as well as Gargouri-Sethom, Samira (1986). Le bijou traditionnel en Tunisie: femmes parées, femmes enchaînées. Aix-en-Provence: Edisud.