Ring Nebula

The Ring Nebula (also catalogued as Messier 57, M57 and NGC 6720) is a planetary nebula in the mildly northern constellation of Lyra.[4][C] Such a nebula is formed when a star, during the last stages of its evolution before becoming a white dwarf, expels a vast luminous envelope of ionized gas into the surrounding interstellar space.

| Emission nebula | |

|---|---|

| Planetary nebula | |

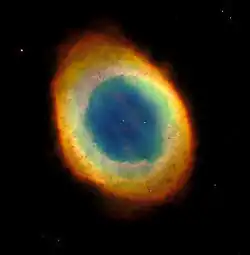

M57, The Ring Nebula (Hubble Space Telescope) | |

| Observation data: J2000 epoch | |

| Right ascension | 18h 53m 35.079s[1] |

| Declination | +33° 01′ 45.03″[1] |

| Distance | 2567±115[1] ly (787±35[1] pc) |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 8.8[2] |

| Apparent dimensions (V) | 230″ × 230″[3] |

| Constellation | Lyra |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Radius | 1.3+0.8 −0.4[a] ly |

| Absolute magnitude (V) | −0.2+0.7 −1.8[b] |

| Notable features | - |

| Designations | M 57,[1] NGC 6720,[1] GC 4447. |

History

This nebula was discovered by the French astronomer Charles Messier while searching for comets in late January 1779. Messier's report of his independent discovery of Comet Bode reached fellow French astronomer Antoine Darquier de Pellepoix two weeks later, who then independently rediscovered the nebula while following the comet. Darquier later reported that it was "...as large as Jupiter and resembles a planet which is fading" (which may have contributed to the use of the persistent "planetary nebula" terminology).[5] It would be entered into Messier's catalogue as the 57th object. Messier and German-born astronomer William Herschel speculated that the nebula was formed by multiple faint stars that were unresolvable with his telescope.[6][7]

In 1800, German Count Friedrich von Hahn announced that he had discovered the faint central star at the heart of the nebula a few years earlier. He also noted that the interior of the ring had undergone changes, and said he could no longer find the central star.[8] In 1864, English amateur astronomer William Huggins examined the spectra of multiple nebulae, discovering that some of these objects, including M57, displayed the spectra of bright emission lines characteristic of fluorescing glowing gases. Huggins concluded that most planetary nebulae were not composed of unresolved stars, as had been previously suspected, but were nebulosities.[9][10] The nebula was first photographed by the Hungarian astronomer Eugene von Gothard in 1886.[8]

Observation

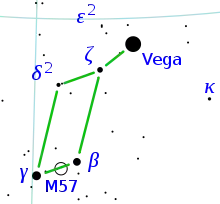

Messier 57 is found south of the bright star Vega, which forms the northwestern vertex of the Summer Triangle asterism. The nebula lies about 40% of the distance from Beta (β) to Gamma (γ) Lyrae, making it an easy target for amateur astronomers to find.[11]

The nebula disk has an angular size of 1.5 × 1 arcminutes, making it too small to be resolved with 10×50 binoculars.[11] It is best observed using a telescope with an aperture of at least 20 cm (8 in), but even a 7.5 cm (3 in) telescope will reveal its elliptical ring shape.[12] Using a UHC or OIII filter greatly enhances visual observation, particularly in light polluted areas. The interior hole can be resolved by a 10 cm (4 in) instrument at a magnification of 100×.[11] Larger instruments will show a few darker zones on the eastern and western edges of the ring, and some faint nebulosity inside the disk.[13] The central star, at magnitude 14.8, is difficult to spot.[12]

Properties

M57 is 0.787 kpc (2,570 light-years) from Earth.[1] It has a visual magnitude of 8.8 and a dimmer photographic magnitude, of 9.7. Photographs taken over a period of 50 years[14] show the rate of nebula expansion is roughly 1 arcsecond per century, which corresponds to spectroscopic observations as 20–30 km s−1. M57 is illuminated by a central white dwarf or planetary nebula nucleus (PNN) of 15.75v visual magnitude.[15]

All the interior parts of this nebula have a blue-green tinge that is caused by the doubly ionized oxygen emission lines at 495.7 and 500.7 nm. These observed so-called "forbidden lines" occur only in conditions of very low density containing a few atoms per cubic centimeter. In the outer region of the ring, part of the reddish hue is caused by hydrogen emission at 656.3 nm, forming part of the Balmer series of lines. Forbidden lines of ionized nitrogen or N II contribute to the reddishness at 654.8 and 658.3 nm.[14]

Nebula structure

M57 is of the class of such starburst nebulae known as bipolar, whose thick equatorial rings visibly extend the structure through its main axis of symmetry. It appears to be a prolate spheroid with strong concentrations of material along its equator. From Earth, the symmetrical axis is viewed at about 30°. Overall, the observed nebulosity has been currently estimated to be expanding for approximately 1,610 ± 240 years.

Structural studies find this planetary exhibits knots characterized by well developed symmetry. However, these are only silhouettes visible against the background emission of the nebula's equatorial ring. M57 may include internal N II emission lines located at the knots' tips that face the PNN; however, most of these knots are neutral and appear only in extinction lines. Their existence shows they are probably only located closer to the ionization front than those found in the Lupus planetary IC 4406. Some of the knots do exhibit well-developed tails which are often detectable in optical thickness from the visual spectrum.[3][16]

Planetary nebula nucleus (PNN)

The central PNN, star that has burst, was discovered by Hungarian astronomer Jenő Gothard on September 1, 1886, from images taken at his observatory in Herény, near Szombathely. Within the last two thousand years, the central star of the Ring Nebula has left the asymptotic giant branch after exhausting its supply of hydrogen fuel. Thus it no longer produces its energy through nuclear fusion and, in evolutionary terms, it is now becoming a compact white dwarf star.

The PNN now consists primarily of carbon and oxygen with a thin outer envelope composed of lighter elements. Its mass is about 0.61–0.62 M☉, with a surface temperature of 125,000 ± 5,000 K. Currently it is 200 times more luminous than the Sun, but its apparent magnitude is only +15.75.[15]

See also

- List of planetary nebulae

- Messier object

- New General Catalogue

- List of Messier objects

- NGC 6565, which is undergoing a similar process and is of the same type

Notes

- ^ Radius = distance × sin(angular size / 2) = 2.3+1.5

−0.7 kly * sin(230″ / 2) = 1.3+0.8

−0.4 ly - ^ 8.8 apparent magnitude − 5 × (log10(700+450

−200 pc distance / 10 pc)) = −0.2+0.7

−1.8 absolute magnitude - ^ Specifically in the north of Lyra which makes it visible from everywhere above about the 47th parallel south. However the Sun passes through Sagittarius far to the south (or technically the Earth orbits so as to make the Sun seem to do so) throughout December. This also makes the cluster mostly risen during day, not night, in the nearest months but will never impede pre-dawn and post-sunset views from the upper half of northerly latitudes.

References

- "M 57". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 2006-12-19.

- Murdin, P. (2000). "Ring Nebula (M57, NGC 6720)". In Paul Murdin (ed.). Encyclopedia of Astronomy and Astrophysics. Institute of Physics Publishing. Bibcode:2000eaa..bookE5323.. doi:10.1888/0333750888/5323. ISBN 978-0-333-75088-9. Article ID #5323.

- O'Dell, C. R.; Balick, B.; Hajian, A. R.; Henney, W. J.; Burkert, A. (2002). "Knots in Nearby Planetary Nebulae". Astronomical Journal. 123 (6): 3329–3347. Bibcode:2002AJ....123.3329O. doi:10.1086/340726.

- Coe, Steven R. (2007). Nebulae and how to observe them. Astronomers' observing guides. Springer. p. 111. ISBN 978-1-84628-482-3.

- Olson, Don; Caglieris, Giovanni Maria (June 2017). "Who Discovered the Ring Nebula?". Sky & Telescope. pp. 32–7.

- Garfinkle, Robert A. (1997). Star-hopping: Your Visa to Viewing the Universe. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-59889-7. OCLC 37355269.

- Messier, Charles (1780). "Catalogue des Nébuleuses & des amas d'Étoiles". Connoissance des Temps for 1783. pp. 225–249.

- Steinicke, Wolfgang (2010). Observing and Cataloguing Nebulae and Star Clusters: From Herschel to Dreyer's New General Catalogue. Cambridge University Press. pp. 42–43. ISBN 978-0-521-19267-5.

- Frommert, Hartmut; Kronberg, Christine. "William Huggins (February 7, 1824 – May 12, 1910)". SEDS. Retrieved 2008-04-11.

- Huggins, W.; Miller, W. A. (1863–1864). "On the Spectra of Some of the Nebulae. And On the Spectra of Some of the Fixed Stars". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 13: 491–493. doi:10.1098/rspl.1863.0094. JSTOR 112077.

- Crossen, Craig; Rhemann, Gerald (2004). Sky Vistas: Astronomy for Binoculars and Richest-field Telescopes. Springer. p. 261. ISBN 978-3-211-00851-5.

- Dunlop, Storm (2005). Atlas of the Night Sky. Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-717223-8.

- "M 57". Messier Objects Mobile — Charts, Maps & Photos. 2016-10-16.

- Karttunen, Hannu (2003). Fundamental Astronomy. Springer. pp. 314. ISBN 978-3-540-00179-9.

- O'Dell, C. R.; Sabbadin, F.; Henney, W. J. (2007). "The Three-Dimensional Ionization Structure and Evolution of NGC 6720, The Ring Nebula". Astronomical Journal. 134 (4): 1679–1692. Bibcode:2007AJ....134.1679O. doi:10.1086/521823.

- O'Dell, C. R.; Balick, B.; Hajian, A. R.; Henney, W. J.; Burkert, A. (2003). "Knots in Planetary Nebulae". Revista Mexicana de Astronomía y Astrofísica, Serie de Conferencias. 15: 29–33. Bibcode:2003RMxAC..15...29O.

External links

- WorldWide Telescope

- M57 Calar Alto Observatory

- Messier 57 SEDS

- Astronomy Picture of the Day

- Infrared Ring Nebula (2005 March 11)

- Ring Nebula Deep Field (2009 November 6)

- M57: The Ring Nebula (2009 November 15)

- The Scale of the Universe - Interactive (2012 March 12)

- M57 – Planetary Nebula in Lyra NightSkyInfo

- M57 The Ring Nebula in Lyra

- M57 ESA/Hubble

- Ring Nebula (M57) in Lyra Constellation Guide (May 26, 2013)

- Szymanek, Nik; Lawrence, Pete. "M57 – Ring Nebula". Deep Sky Videos. Brady Haran.

- The Ring Nebula on WikiSky: DSS2, SDSS, GALEX, IRAS, Hydrogen α, X-Ray, Astrophoto, Sky Map, Articles and images