Schism

A schism (/ˈsɪzəm/ SIZ-əm, /ˈskɪzəm/, SKIZ-əm or, less commonly, /ˈʃɪzəm/ SHIZ-əm)[1] is a division between people, usually belonging to an organization, movement, or religious denomination. The word is most frequently applied to a split in what had previously been a single religious body, such as the Great East–West Schism or the Western Schism. It is also used of a split within a non-religious organization or movement or, more broadly, of a separation between two or more people, be it brothers, friends, lovers, etc.

A schismatic is a person who creates or incites schism in an organization or who is a member of a splinter group. Schismatic as an adjective means pertaining to a schism or schisms, or to those ideas, policies, etc. that are thought to lead towards or promote schism.

In religion, the charge of schism is distinguished from that of heresy, since the offence of schism concerns not differences of belief or doctrine but promotion of, or the state of division,[2] especially among groups with differing pastoral jurisdictions and authority. However, schisms frequently involve mutual accusations of heresy, and also that of the Great Apostasy. In Roman Catholic teaching, every heresy is a schism, while there may be some schisms free of the added guilt of heresy.[3] Liberal Protestantism, however, has often preferred heresy over schism. Presbyterian scholar James I. McCord (quoted with approval by the Episcopalian Bishop of Virginia, Peter Lee) drew a distinction between them, teaching: "If you must make a choice between heresy and schism, always choose heresy. As a schismatic, you have torn and divided the body of Christ. Choose heresy every time."[4] ("Choose heresy" is a pun; "heresy" is a Latinization of an ancient Greek word for "choice".)

Etymology

The word schism comes from the Greek word σχίσμα which means "cleft, division".

Buddhism

In Buddhism, the first schism was set up by Devadatta, during Buddha's life. This schism lasted only a short time. Later (after Buddha's death), the early Buddhist schools came into being, but were not schismatic, only focusing on different interpretations for the same monastic community. In the old texts, 18 or 20 early schools are mentioned. Later, there were the Mahayana and Vajrayana movements, which can be regarded as being schismatic in origin. Each school has various subgroups, which often are schismatic in origin. For example, in Thai Theravadin Buddhism there are two groups (Mahanikaya and Dhammayut), of which the Dhammayut has its origin partly in the Mahanikaya, and is the new and schismatic group. Both Mahanikaya and Dhammayut have many subgroups, which usually do not have schismatic origins, but came into being in a natural way, through the popularity of a (leader) monk. Tibetan Buddhism has seen schisms in the past, of which most were healed, although the Drukpa school centred in Bhutan perhaps remains in a state of schism (since 1616) from the other Tibetan schools.

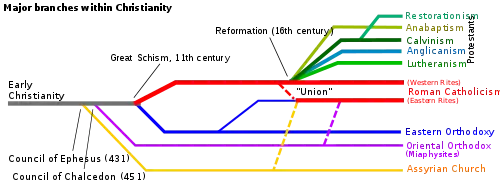

Christianity

The words schism and schismatic have found their heaviest usage in the history of Christianity, to denote splits within a church, denomination or religious body. In this context, "schismatic", as a noun, denotes a person who creates or incites schism in a church or a person who is a member of a splinter Church; as an adjective, "schismatic" refers to ideas and activities that are thought to lead to or constitute schism, and ultimately to departure from what the user of the word considers to be the true Christian Church. These words have been used to denote both the phenomenon of Christian group-splintering in general, and certain significant historical splits in particular.

One can make a distinction[5] between heresy and schism. Heresy is rejection of a doctrine that a Church considered to be essential. Schism is a rejection of communion with the authorities of a Church, and not every break of communion is necessarily about doctrine, as is clear from examples such as the Western Schism and the breaking of the communion that existed between Patriarch Bartholomew I of Constantinople and Archbishop Christodoulos of Athens in 2004.[6] However, when for any reason people withdraw from communion, two distinct ecclesiastical entities may result, each of which, or at least some members thereof, may then accuse the other(s) of heresy.

In Roman Catholic Church canon law, an act of schism, like an act of apostasy or heresy, automatically brings the penalty of excommunication on the individual who commits it.[7] As stated in canon 1312 §1 1° of the 1983 Code of Canon Law, this penalty is intended to be medicinal, so as to lead to restoration of unity. Roman Catholic theology considers formal schismatics to be outside the Church, understanding by "formal schismatics" "persons who, knowing the true nature of the Church, have personally and deliberately committed the sin of schism".[8] The situation, for instance, of those who have been brought up from childhood within a group not in full communion with Rome, but who have orthodox faith, is different: these are considered to be imperfectly, though not fully, related to the Church.[8] This nuanced view applies especially to the Churches of Eastern Christianity, more particularly still to the Eastern Orthodox Church.[8] While they don't possess "full communion" (communio in sacris) with the Catholic Church, they are still considered much more linked to it than the Protestant ecclesial communities, which have markedly different theological beliefs and rejected the concept of apostolic succession (with the exception of the Anglicans, which, however, are viewed by the Catholic Church as not having a valid priesthood).

The First Council of Nicaea (A.D. 325) distinguished between schism and heresy. It declared Arian and non-Trinitarian teachings to be heretical and excluded their adherents from the Church. It also addressed the schism between Peter of Alexandria and Meletius of Lycopolis, considering their quarrel to be a matter of discipline, not of faith.

The divisions that came to a head at the Councils of Ephesus (A.D. 431) and Chalcedon (A.D. 451) were seen as matters of heresy, not merely of schism. Thus the Eastern Orthodox Church and Oriental Orthodoxy regard each other as heretical, not orthodox, because of the Oriental Orthodox Church's rejection and the Eastern Orthodox Church's acceptance of the Confession of Chalcedon about the two natures (human and divine) of Christ. However, this view has been challenged in the recent Ecumenical discussion between these two groups, classifying the matter of Chalcedon as a matter of schism, not of heresy.

In its extended and final form (possibly derived from the First Council of Constantinople in 381 although only known from the Acts of the Council of Chalcedon seventy years later),[9] what is commonly called the Nicene Creed declares belief in the One Holy Catholic and Apostolic Church. Some who accept this creed believe they should be united in a single Church or group of Churches in communion with each other. Others who accept this creed believe it does not speak of a visible organization but of all those baptized who hold the Christian faith, referred to as "Christendom". Some churches consider themselves to be the One Holy Catholic and Apostolic Church. For instance, the Roman Catholic Church claims that title and considers the Eastern Orthodox Church to be in schism, while the Eastern Orthodox Church also claims that title and holds the view that the Catholic Church is schismatic. Some Protestant Churches believe that they also represent the One Holy Catholic and Apostolic Church and consider the Catholic and Orthodox Churches to be in error, while others do not expect a union of all Christian churches on earth. See also One true church and Great Apostasy.

Protestant groups, lacking the stronger traditional authority-structures of (say) Roman Catholicism or Eastern Orthodoxy, and often riven by politico-national divides (sometimes resulting from cuius regio, eius religio), show a high degree of fissibility, which ecumenical efforts may only intensify.[10]

Schisms have occurred particularly frequently among Anabaptists, to the extent that divisions over even minute details of doctrine and theology are common and scholars have dubbed the phenomenon Täuferkrankheit or "The Anabaptist Disease".[11] Emphasizing fully voluntary membership in the church, and without an established authority of hierarchical structure, Anabaptists, especially Mennonites have experienced dozens of schisms, resulting in the establishment of dozens of various unaffiliated Mennonite churches.

A current dispute with an acknowledged risk of schism for the Anglican Communion involves responses to homosexuality.

In 2018 Eastern Orthodoxy suffered a schism, the 2018 Moscow-Constantinople schism between the primatial See of Eastern Orthodoxy, the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople and the Russian Orthodox Church over the issue of Constantinople granting autocephaly to the Orthodox Church of Ukraine.

Hinduism

The Kanchi Math was originally established as the Kumbakonam Mutt in 1821 by the Maratha king of Tanjore, Serfoji II Bhonsle, as a branch of the Sringeri Mutt, one of the four cardinal Shankaracharya Maths of the mainstream Smarta denomination. It became a schismatic institution when Tanjore and the Wodeyars of Mysore went to war against each other. It is on record that in 1839 the Kumbakonam Mutt applied for permission to the English Collector of Arcot to perform the “kumbhabhishekham” of the Kamakshi temple in Kanchipuram

In 1842, the East India Company headquartered at Fort William, Calcutta appointed the head of the mutt as the sole trustee of the Kamakshi temple. The protests of the traditional priests of the Kamakshi temple are well documented and preserved. Incidentally, Fort William is also the first Freemason lodge of India.[12] Since then, the Math has maintained cordial relations with the British Raj though the main math at Sringeri fell sour with the colonial power[13]

Thus, the Kanchi Mutt can at best claim its origin to be in 1842.[14][15]

Islam

After the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, there have arisen many Muslim sects by means of schools of thought, traditions and related faiths.[16][17] According to a hadith report (collections of accounts of the life and teachings of Muhammad), Muhammad is said to have prophesied "My Ummah (Community or Nation) will be fragmented into seventy-three sects, and all of them will be in the Hell fire except one." The Sahaba (his companions) asked him which group that would be, whereupon he replied, "It is the one to which I and my companions belong" (reported in Sunan al-Tirmidhi Hadith No. 171).

Sunni Muslims, often referred to as Ahl as-Sunnah wa’l-Jamā‘h or Ahl as-Sunnah, are the largest denomination of Islam. The word Sunni comes from the word Sunnah, which means the teachings and actions or examples of the Islamic prophet, Muhammad; therefore, the term Sunni refers to those who follow or maintain the Sunnah of Muhammad. The Sunni believe that Muhammad died without appointing a successor to lead the Ummah (Muslim community). After an initial period of confusion, a group of his most prominent companions gathered and elected Abu Bakr, Muhammad's close friend and father-in-law, as the first Caliph. Sunnis regard the first four caliphs - Abu Bakr, Umar (`Umar ibn al-Khattāb), Uthman Ibn Affan, and Ali (Ali ibn Abu Talib) - as the al-Khulafā’ur-Rāshidūn or "Rashidun" (The Rightly Guided Caliphs). Sunnis believe that the position of Caliph may be democratically chosen, but after the first four Rightly Guided Caliphs the position turned into a hereditary dynastic rule. There has not been another widely recognized Caliph since the fall of the Ottoman Empire in 1923.

Shia Islam is the second largest denomination of Islam. Shia Muslims believe that, similar to the appointment of prophets, Imams after Muhammad are also chosen by God. According to Shias, Ali was chosen by Allah and thus appointed by Muhammad to be the direct successor and leader of the Muslim community. They regard him as the first Shia Imam, which continued as a hereditary position through Fatimah and Ali's descendants.

Sufism is a mystical-ascetic form of Islam practised by both Shia and Sunni Muslims. Some Sufi followers consider themselves Sunni or Shia, while others consider themselves as just Sufi or Sufi-influenced. Sufism is usually considered to be complementary to orthodox Islam, although Sufism has often been accused by the salafi of being an unjustified Bid‘ah or religious innovation. By focusing on the more spiritual aspects of religion, Sufis strive to obtain direct experience of God by making use of "intuitive and emotional faculties" that one must be trained to use.[18] One starts with sharia (Islamic law), the exoteric or mundane practice of Islam, and then is initiated into the mystical (esoteric) path of a Tariqah (Sufi Order).

Kharijite (lit. "those who seceded") is a general term embracing a variety of Islamic sects which, while originally supporting the Caliphate of Ali, eventually rejected his legitimacy after he negotiated with Mu'awiya during the 7th Century Islamic civil war (First Fitna).[19] Their complaint was that the Imam must be spiritually pure, whereas Ali's compromise with Mu'awiya was a compromise of his spiritual purity and therefore of his legitimacy as Imam or Caliph. While there are few remaining Kharijite or Kharijite-related groups, the term is sometimes used to denote Muslims who refuse to compromise with those with whom they disagree.

Dates:

- The schism of the Shia and Sunni, c. 632/680s

- The schism of the Kharijites, late 7th century

- The schism of the Mu'tazilites, 8th century

- The schism of the Mihna, c. 833

- The schism of Zikri, c. 1500

- The schism of Ahmadiyya, 19th century

- The Moorish Science Temple of America, c. 1913

- The Nation of Islam, c. 1930

- The United Submitters International, c. mid-20th century

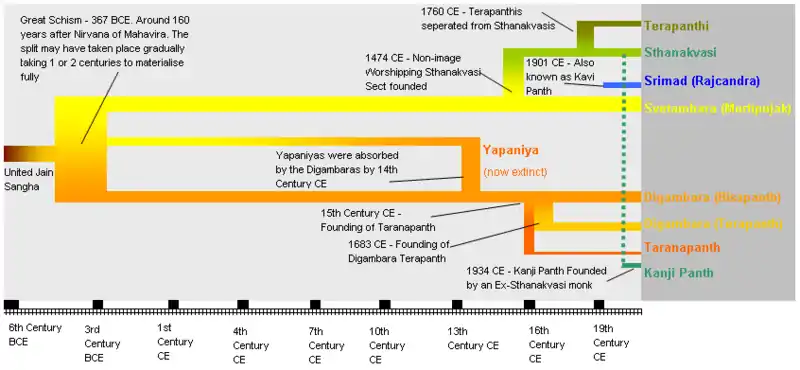

Jainism

The first schism in Jainism happened around the fourth century BCE, leading to rise of two major sects, Digambara and Svetambara, which were later subdivided in further sub-sects.[20]

Judaism

Major Jewish denominations are Orthodox Judaism and non-Orthodox: Reform, Conservative and Reconstructionist. In early Jewish history, the Jewish and Samaritan religions were the product of the schism during the Babylonian Exile (6thC BCE). Schisms in Judaism included the emergence of Christianity.

Dates:

- Samaritanism, 586 BCE

- Christianity, c. 1st century AD

- Reform Judaism, 1810

- Conservative Judaism, 1886

See also

- One true church

- List of schisms in Christianity

- Secession

- Old and New Light

Notes

- The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 4th ed. (2000) notes in The Free Dictionary that "The word schism, which was originally spelled scisme in English, is traditionally pronounced (sĭ′zəm). However, in the 16th century the word was respelled with an initial sch in order to conform to its Latin and Greek forms. From this spelling arose the pronunciation (skĭ′zəm). Long regarded as incorrect, it became so common in both British and American English that it gained acceptability as a standard variant. Evidence indicates, however, that it is now the preferred pronunciation, at least in American English. In a recent survey 61 percent of the Usage Panel indicated that they use (skĭ′zəm), while 31 percent said they use (sĭ′zəm). A smaller number, 8 percent, preferred a third pronunciation, (shĭ′zəm)."

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 327.

- Forget, Jacques (1912). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 13. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- "Heresy better idea than schism?". Washington Times. 2004-01-31. Retrieved 2010-07-05.

- Catechism of the Eastern Orthodox Church, p. 42; The Concordia Cyclopedia quoted in Unionism and Syncretism - and PLI; Orthodox Practice - Choosing God-parents; Code of Canon Law, canon 751

- "Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople Broke Eucharistic Communion with Archbishop Christodoulos of Athens » News » OrthodoxEurope.org". orthodoxeurope.org.

- Code of Canon Law, canon 1364

- Aidan Nichols, Rome and the Eastern Churches (Liturgical Press 1992), p. 41 ISBN 978-1-58617-282-4

- Kelly, J.N.D. Early Christian Creeds Longmans 1960 pp. 296,7; 305-331

-

Leithart, Peter J. (2016-10-18). "The Case against Denominationalism: Perpetuating Schism". The End of Protestantism: Pursuing Unity in a Fragmented Church. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Publishing Group. p. 78. ISBN 9781493405831. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

The causes of church division are complex, and the effects can be paradoxical. In a study of American Protestant schisms between 1890 and 1990, John Sutton and Mark Chaves conclude that churches do not divide for purely doctrinal reasons but rather 'in response to attempts by denominational elites to achieve organizational consolidation.' [...] Ironically, 'mergers and foundings sharply raise the likelihood of schism.' Efforts to reunite the church can go wrong and sow further and deeper divisions. Ironically again, schism can reduce the chance of schism, though only briefly: 'one year after a founding or merger, rates of schism are five times higher than they are one year after a schism.'

- Schisms "Schisms". gameo.rg.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - Deschamps, Simon (2017-06-15). "From Britain to India: Freemasonry as a Connective Force of Empire". E-rea. Revue électronique d'études sur le monde anglophone. 14 (2). doi:10.4000/erea.5853. ISSN 1638-1718.

- "Sringeri temple attack and the genocide of Karnataka's Hindus by the Maratha Empire (1791)". History of Islam. 2020-10-31. Retrieved 2022-01-04.

- Guruswamy, Mohan (2021-11-30). "Mohan Guruswamy | The Kumbakonam of the Kanchi Shankaracharya". Deccan Chronicle. Retrieved 2022-01-04.

- "ஆதி சங்கரர் நிறுவியதா காஞ்சி சங்கரமடம்? – முரண்படும் தகவல்கள்". BBC News தமிழ் (in Tamil). 2018-03-01. Retrieved 2022-01-04.

- Editor. "Islam News Room - Quran 'Miracle 19' is A Lie?". www.islamnewsroom.com.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - Why are Muslims divided into different Sects/Schools of Thought Archived 2008-09-15 at the Wayback Machine by Zakir Naik on IRF.net

- Trimingham (1998), p.1

- Pike, John. "Kharijite Islam". www.globalsecurity.org.

- Clarke & Beyer 2009, p. 326.

References

- Clarke, Peter; Beyer, Peter (2009), The World's Religions: Continuities and Transformations, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-203-87212-3