Seborrhoeic dermatitis

Seborrhoeic dermatitis, sometimes inaccurately referred to as seborrhoea, is a long-term skin disorder.[4] Symptoms include red, scaly, greasy, itchy, and inflamed skin.[2][3] Areas of the skin rich in oil-producing glands are often affected including the scalp, face, and chest.[4] It can result in social or self-esteem problems.[4] In babies, when the scalp is primarily involved, it is called cradle cap.[2] Dandruff is a milder form of the condition without inflammation.[6]

| Seborrhoeic dermatitis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Sebopsoriasis, seborrhoeic eczema, pityriasis capitis[1] |

| |

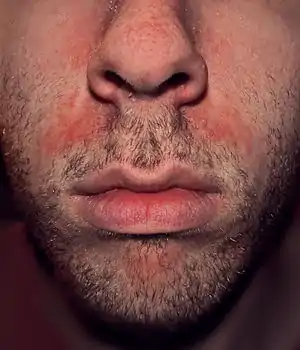

| An example of seborrhoeic dermatitis between the nose and mouth | |

| Specialty | Dermatology |

| Symptoms | Itchy, flaking, greasy, red, and inflamed skin[2][3] |

| Duration | Long term[4] |

| Causes | Multiple factors[4] |

| Risk factors | Stress, winter, poor immune function, Parkinson disease[4] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms[4] |

| Differential diagnosis | Psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, tinea capitis, rosacea, systemic lupus erythematosus[4] |

| Treatment | Humidifier |

| Medication | Antifungal cream, anti-inflammatory agents, coal tar, phototherapy[3] |

| Frequency | ~5% (adults),[4] ~10% (babies)[5] |

The cause is unclear but believed to involve a number of genetic and environmental factors.[2][4] Risk factors include poor immune function, Parkinson's disease, and alcoholic pancreatitis.[4][6] The condition may worsen with stress or during the winter.[4] The Malassezia yeast is believed to play a role.[6] It is not a result of poor hygiene.[7] Diagnosis is typically based on the symptoms.[4] The condition is not contagious.[8]

The typical treatment is antifungal cream and anti-inflammatory agents.[3] Specifically, ketoconazole or ciclopirox are effective.[9] It is unclear if other antifungals, such as miconazole, are equally effective as they have been poorly studied.[9] Other options may include salicylic acid, coal tar, benzoyl peroxide, and phototherapy.[3]

The condition is most common in infants within the first 3 months or in adults aged 30 to 70 years.[2] In adults between 1% and 10% of people are affected.[4] Males are more often affected than females.[4] Up to 70% of babies may be affected at some point in time.[5]

Signs and symptoms

Seborrhoeic dermatitis' symptoms appear gradually, and usually the first signs are flaky skin and scalp.[10] Symptoms occur most commonly anywhere on the skin of the scalp, behind the ears, on the face, and in areas where the skin folds. Flakes may be yellow, white or grayish.[11] Redness and flaking may also occur on the skin near the eyelashes, on the forehead, around the sides of the nose, on the chest, and on the upper back.

In more severe cases, yellowish to reddish scaly pimples appear along the hairline, behind the ears, in the ear canal, on the eyebrows, on the bridge of the nose, around the nose, on the chest, and on the upper back.[12]

Commonly, patients experience mild redness, scaly skin lesions and in some cases hair loss.[13] Other symptoms include patchy scaling or thick crusts on the scalp, red, greasy skin covered with flaky white or yellow scales, itching, soreness and yellow or white scales that may attach to the hair shaft.[14]

Seborrhoeic dermatitis can occur in infants younger than three months and it causes a thick, oily, yellowish crust around the hairline and on the scalp. Itching is not common among infants. Frequently, a stubborn diaper rash accompanies the scalp rash.[12]

Causes

The cause of seborrhoeic dermatitis has not been fully clarified.[1][15]

In addition to the presence of Malassezia, genetic, environmental, hormonal, and immune-system factors are necessary for and/or modulate the expression of seborrhoeic dermatitis.[16][17] The condition may be aggravated by illness, psychological stress, fatigue, sleep deprivation, change of season, and reduced general health.[18] In children and babies, excessive vitamin A intake[19] or issues with Δ6-desaturase enzymes[18] have been correlated with increased risk. Seborrhoeic dermatitis-like eruptions are also associated with vitamin B6 deficiency.[20] Those with immunodeficiency (especially infection with HIV) and with neurological disorders such as Parkinson's disease (for which the condition is an autonomic sign) and stroke are particularly prone to it.[21]

Climate

Low humidity and low temperature are responsible for high frequency of seborrheic dermatitis.[22]

Fungi

The condition is thought to be due to a local inflammatory response to over-colonization by Malassezia fungi species in sebum-producing skin areas including the scalp, face, chest, back, underarms, and groin.[3][15] This is based on observations of high counts of Malassezia species in skin affected by seborrhoeic dermatitis and on the effectiveness of antifungals in treating the condition.[15] Such species of Malassezia include M. furfur (formerly Pityrosporum ovale), M. globosa, M. restricta, M. sympodialis, and M. slooffiae.[3] Although Malassezia appears to be the central predisposing factor in seborrhoeic dermatitis, it is thought that other factors are necessary for the presence of Malassezia to result in the pathology characteristic of the condition.[15] This is based on the fact that summer growth of Malassezia in the skin alone does not result in seborrhoeic dermatitis.[15] Besides antifungals, the effectiveness of anti-inflammatory drugs, which reduce inflammation, and antiandrogens, which reduce sebum production, provide further insights into the pathophysiology of seborrhoeic dermatitis.[3][23][24]

Management

Humidity

A humidifier can be used to prevent low indoor humidity during winter (especially with indoor heating), and dry season. And a dehumidifier can be used during seasons with excessive humidity.

Medications

A variety of different types of medications are able to reduce symptoms of seborrhoeic dermatitis.[3] These include certain antifungals, anti-inflammatory agents like corticosteroids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antiandrogens, and antihistamines, among others.[3][1]

Antifungals

Regular use of an over-the-counter or prescription antifungal shampoo or cream may help those with recurrent episodes. The topical antifungal medications ketoconazole and ciclopirox have the best evidence.[9] It is unclear if other antifungals are equally effective as this has not been sufficiently studied.[9] Antifungals that have been studied and found to be effective in the treatment of seborrhoeic dermatitis include ketoconazole, fluconazole, miconazole, bifonazole, sertaconazole, clotrimazole, flutrimazole, ciclopirox, terbinafine, butenafine, selenium sulfide, and lithium salts such as lithium gluconate and lithium succinate.[9][3] Topical climbazole appears to have little effectiveness in the treatment of seborrhoeic dermatitis.[9] Systemic therapy with oral antifungals including itraconazole, fluconazole, ketoconazole, and terbinafine is effective.[3]

Anti-inflammatory treatments

Topical corticosteroids have been shown to be effective in short-term treatment of seborrhoeic dermatitis and are as effective or more effective than antifungal treatment with azoles. There is also evidence for the effectiveness of calcineurin inhibitors like tacrolimus and pimecrolimus as well as lithium salt therapy.[25]

Oral immunosuppressive treatment, such as with prednisone, has been used in short courses for seborrhoeic dermatitis, as a last resort due to its potential side effects.[26]

Antiandrogens

Seborrhoea, which is sometimes associated with seborrhoeic dermatitis,[27][28][29] is recognized as an androgen-sensitive condition – that is, it is caused or aggravated by androgen sex hormones such as testosterone and dihydrotestosterone – and is a common symptom of hyperandrogenism (e.g., that seen in polycystic ovary syndrome).[30][31] In addition, seborrhoea, as well as acne, are commonly associated with puberty due to the steep increase of androgen levels at that time.[32]

In accordance with the involvement of androgens in seborrhoea, antiandrogens, such as cyproterone acetate,[33] spironolactone,[34] flutamide,[35][36] and nilutamide,[37][38] are highly effective in alleviating the condition.[30][39] As such, they are used in the treatment of seborrhoea,[30][39] particularly severe cases.[40] While beneficial in seborrhoea, effectiveness may vary with different antiandrogens; for instance, spironolactone (which is regarded as a relatively weak antiandrogen) has been found to produce a 50% improvement after three months of treatment, whereas flutamide has been found to result in an 80% improvement within three months.[30][36] Cyproterone acetate, similarly more potent and effective than spironolactone, results in considerable improvement or disappearance of acne and seborrhoea in 90% of patients within three months.[41]

Systemic antiandrogen therapy is generally used to treat seborrhoea only in women, not in men, as these medications can result in feminization (e.g., gynecomastia), sexual dysfunction, and infertility in males.[42][43] In addition, antiandrogens theoretically have the potential to feminize male fetuses in pregnant women and, for this reason, are usually combined with effective birth control in sexually active women who can or may become pregnant.[41]

Antihistamines

Antihistamines are used primarily to reduce itching, if present. However, research studies suggest that some antihistamines have anti-inflammatory properties.[44]

Other treatments

- Coal tar can be effective. Although no significant increased risk of cancer in human treatment with coal tar shampoos has been found,[45] caution is advised since coal tar is carcinogenic in animals, and heavy human occupational exposures do increase cancer risks.

- Isotretinoin, a sebosuppressive agent, may be used to reduce sebaceous gland activity as a last resort in refractory disease.[29] However, isotretinoin has potentially serious side effects, and few patients with seborrhoeic dermatitis are appropriate candidates for therapy.[26]

- Keratolytics like topical urea[46]

- Metronidazole[9]

- Topical 4% nicotinamide[3]

Phototherapy

Another potential option is natural and artificial UV radiation since it can curb the growth of Malassezia yeast.[47] Some recommend photodynamic therapy using UV-A and UV-B laser or red and blue LED light to inhibit the growth of Malassezia fungus and reduce seborrhoeic inflammation.[47][48][49]

Epidemiology

Seborrhoeic dermatitis affects 1 to 5% of the general population.[1][50][51] It is slightly more common in men, but affected women tend to have more severe symptoms.[51] The condition usually recurs throughout a person's lifetime.[52] Seborrhoeic dermatitis can occur in any age group[52] but usually starts at puberty and peaks in incidence at around 40 years of age.[53] It can reportedly affect as many as 31% of older people.[51] Severity is worse in dry climates.[52] Seborrhoeic dermatitis is common in people with alcoholism, between 7 and 11 percent, which is twice the normal expected occurrence.[54]

See also

- Seborrheic keratosis

- Eczema herpeticum, condition that primarily manifests in childhood

References

- Dessinioti C, Katsambas A (Jul–Aug 2013). "Seborrheic dermatitis: etiology, risk factors, and treatments: facts and controversies". Clinics in Dermatology. 31 (4): 343–351. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.01.001. PMID 23806151.

- "Seborrheic Dermatitis - Dermatologic Disorders". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- Borda LJ, Perper M, Keri JE (March 2019). "Treatment of seborrheic dermatitis: a comprehensive review". The Journal of Dermatological Treatment. 30 (2): 158–169. doi:10.1080/09546634.2018.1473554. PMID 29737895. S2CID 13686180.

- Ijaz N, Fitzgerald D (June 2017). "Seborrhoeic dermatitis". British Journal of Hospital Medicine. 78 (6): C88–C91. doi:10.12968/hmed.2017.78.6.C88. PMID 28614013.

- Nobles T, Harberger S, Krishnamurthy K (August 2021). "Cradle Cap". StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30285358.

- Naldi L, Diphoorn J (May 2015). "Seborrhoeic dermatitis of the scalp". BMJ Clinical Evidence. 2015. PMC 4445675. PMID 26016669.

- "Seborrheic dermatitis". American Academy of Dermatology. Archived from the original on 21 October 2017. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- "Seborrheic Dermatitis: What is It, Diagnosis & Treatment". Cleveland, Ohio: Cleveland Clinic.

- Okokon EO, Verbeek JH, Ruotsalainen JH, Ojo OA, Bakhoya VN (May 2015). Okokon EO (ed.). "Topical antifungals for seborrhoeic dermatitis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4 (5): CD008138. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008138.pub3. PMC 4448221. PMID 25933684.

- "Dermatitis Seborrheic Treatment". Archived from the original on 2010-06-02. Retrieved June 11, 2010.

- "Seborrheic Dermatitis". Archived from the original on June 15, 2010. Retrieved June 11, 2010.

- "Dermatitis". Archived from the original on September 25, 2011. Retrieved June 11, 2010.

- "What is Seborrheic Dermatitis?". Archived from the original on April 20, 2010. Retrieved June 11, 2010.

- "Symptoms". Archived from the original on May 26, 2010. Retrieved June 11, 2010.

- Wikramanayake TC, Borda LJ, Miteva M, Paus R (September 2019). "Seborrheic dermatitis-Looking beyond Malassezia". Experimental Dermatology. 28 (9): 991–1001. doi:10.1111/exd.14006. PMID 31310695.

- Johnson BA, Nunley JR (May 2000). "Treatment of seborrheic dermatitis". American Family Physician. 61 (9): 2703–10, 2713–4. PMID 10821151. Archived from the original on 2010-07-06.

- Janniger CK, Schwartz RA (July 1995). "Seborrheic dermatitis". American Family Physician. 52 (1): 149–55, 159–60. PMID 7604759.

- Schwartz RA, Janusz CA, Janniger CK (July 2006). "Seborrheic dermatitis: an overview". American Family Physician. 74 (1): 125–130. PMID 16848386.

- MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Hypervitaminosis A

- Alamgir AN (2018). Therapeutic Use of Medicinal Plants and their Extracts: Volume 2: Phytochemistry and Bioactive Compounds. Springer. p. 435. ISBN 978-3319923871.

- "Seborrhoeic dermatitis and dandruff (seborrheic eczema). DermNet NZ". . DermNet NZ. 2012-03-20. Archived from the original on 2012-06-15. Retrieved 2012-06-10.

- Araya M, Kulthanan K, Jiamton S (September 2015). "Clinical Characteristics and Quality of Life of Seborrheic Dermatitis Patients in a Tropical Country". Indian Journal of Dermatology. 60 (5): 519. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.164410. PMC 4601435. PMID 26538714.

- Trivedi MK, Shinkai K, Murase JE (March 2017). "A Review of hormone-based therapies to treat adult acne vulgaris in women". International Journal of Women's Dermatology. 3 (1): 44–52. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.02.018. PMC 5419026. PMID 28492054.

- Paradisi R, Fabbri R, Porcu E, Battaglia C, Seracchioli R, Venturoli S (October 2011). "Retrospective, observational study on the effects and tolerability of flutamide in a large population of patients with acne and seborrhea over a 15-year period". Gynecological Endocrinology. 27 (10): 823–829. doi:10.3109/09513590.2010.526664. PMID 21117864. S2CID 20250916.

- Kastarinen H, Oksanen T, Okokon EO, Kiviniemi VV, Airola K, Jyrkkä J, et al. (May 2014). "Topical anti-inflammatory agents for seborrhoeic dermatitis of the face or scalp". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (5): CD009446. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009446.pub2. PMC 6483543. PMID 24838779.

- Gupta AK, Richardson M, Paquet M (January 2014). "Systematic review of oral treatments for seborrheic dermatitis". Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 28 (1): 16–26. doi:10.1111/jdv.12197. PMID 23802806. S2CID 25441626.

- "Seborrhoeic dermatitis | DermNet NZ". dermnetnz.org. Retrieved 2021-09-20.

- Burton JL, Pye RJ (April 1983). "Seborrhoea is not a feature of seborrhoeic dermatitis". British Medical Journal. 286 (6372): 1169–1170. doi:10.1136/bmj.286.6372.1169. PMC 1547390. PMID 6220754.

- de Souza Leão Kamamoto C, Sanudo A, Hassun KM, Bagatin E (January 2017). "Low-dose oral isotretinoin for moderate to severe seborrhea and seborrheic dermatitis: a randomized comparative trial". International Journal of Dermatology. 56 (1): 80–85. doi:10.1111/ijd.13408. PMID 27778328. S2CID 13049459.

- Singh SM, Gauthier S, Labrie F (February 2000). "Androgen receptor antagonists (antiandrogens): structure-activity relationships". Current Medicinal Chemistry. 7 (2): 211–247. doi:10.2174/0929867003375371. PMID 10637363.

- Zouboulis CC, Degitz K (2004). "Androgen action on human skin -- from basic research to clinical significance". Experimental Dermatology. 13 (s4): 5–10. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0625.2004.00255.x. PMID 15507105. S2CID 34863608.

- Handelsman DJ (October 2020). "Androgen Physiology, Pharmacology, Use and Misuse". In Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, Chrousos G, de Herder WW, Dhatariya K, et al. (eds.). Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc. PMID 25905231.

- Becker KL (2001). Principles and Practice of Endocrinology and Metabolism. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1004–. ISBN 978-0-7817-1750-2. Archived from the original on 2013-06-02.

- Plewig G, Kligman AM (6 December 2012). ACNE and ROSACEA. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 66, 685, 687. ISBN 978-3-642-59715-2. Archived from the original on 19 March 2017.

- Farid NR, Diamanti-Kandarakis E (27 February 2009). Diagnosis and Management of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 240–. ISBN 978-0-387-09718-3. Archived from the original on 19 March 2017.

- Diamanti-Kandarakis E (September 1999). "Current aspects of antiandrogen therapy in women". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 5 (9): 707–23 (717). PMID 10495361.

- Couzinet B, Thomas G, Thalabard JC, Brailly S, Schaison G (July 1989). "Effects of a pure antiandrogen on gonadotropin secretion in normal women and in polycystic ovarian disease". Fertility and Sterility. 52 (1): 42–50. doi:10.1016/s0015-0282(16)60786-0. PMID 2744186.

- Namer M (October 1988). "Clinical applications of antiandrogens". Journal of Steroid Biochemistry. 31 (4B): 719–729. doi:10.1016/0022-4731(88)90023-4. PMID 2462132.

- Mutschler HD (1995). Drug Actions: Basic Principles and Therapeutic Aspects. CRC Press. pp. 304–. ISBN 978-0-8493-7774-7. Archived from the original on 2017-11-05.

- DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, Matzke GR, Wells BG, Posey LM (6 July 2008). Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach. McGraw Hill Professional. p. 1598. ISBN 978-0-07-164325-2. Archived from the original on 19 March 2017.

- Hughes A, Hasan SH, Oertel GW, Voss HE, Bahner F, Neumann F, et al. (27 November 2013). Androgens II and Antiandrogens / Androgene II und Antiandrogene. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 351, 516. ISBN 978-3-642-80859-3. Archived from the original on 19 March 2017.

- Millikan LE (19 April 2016). Drug Therapy in Dermatology. CRC Press. pp. 295–. ISBN 978-0-203-90831-0. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017.

- Brenner S (13 December 2013). The Clinical Nanomedicine Handbook. CRC Press. pp. 97–. ISBN 978-1-4398-3478-7. Archived from the original on 5 November 2017.

- Grob JJ, Castelain M, Richard MA, Bonniol JP, Béraud V, Adhoute H, et al. (May 1998). "Antiinflammatory properties of cetirizine in a human contact dermatitis model. Clinical evaluation of patch tests is not hampered by antihistamines". Acta Dermato-Venereologica. 78 (3): 194–197. doi:10.1080/000155598441512. PMID 9602225.

- Roelofzen JH, Aben KK, Oldenhof UT, Coenraads PJ, Alkemade HA, van de Kerkhof PC, et al. (April 2010). "No increased risk of cancer after coal tar treatment in patients with psoriasis or eczema". The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 130 (4): 953–961. doi:10.1038/jid.2009.389. PMID 20016499.

- Piquero-Casals J, Hexsel D, Mir-Bonafé JF, Rozas-Muñoz E (September 2019). "Topical Non-Pharmacological Treatment for Facial Seborrheic Dermatitis". Dermatology and Therapy. 9 (3): 469–477. doi:10.1007/s13555-019-00319-0. PMC 6704200. PMID 31396944.

- Wikler JR, Janssen N, Bruynzeel DP, Nieboer C (1990). "The effect of UV-light on pityrosporum yeasts: ultrastructural changes and inhibition of growth". Acta Dermato-Venereologica. 70 (1): 69–71. PMID 1967880.

- Calzavara-Pinton PG, Venturini M, Sala R (January 2005). "A comprehensive overview of photodynamic therapy in the treatment of superficial fungal infections of the skin". Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology. B, Biology. 78 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2004.06.006. PMID 15629243.

- Maisch T, Szeimies RM, Jori G, Abels C (October 2004). "Antibacterial photodynamic therapy in dermatology". Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences. rsc.org. 3 (10): 907–917. doi:10.1039/B407622B. PMID 15480480.

- Goldstein MA, Goldstein MC, Credit LP (17 March 2009). Your Best Medicine: From Conventional and Complementary Medicine--Expert-Endorsed Therapeutic Solutions to Relieve Symptoms and Speed Healing. Rodale. pp. 462–. ISBN 978-1-60529-656-2. Archived from the original on 5 November 2017.

- Farage MA, Miller KW, Maibach HI (2 December 2009). Textbook of Aging Skin. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 534–. ISBN 978-3-540-89655-5. Archived from the original on 5 November 2017.

- Jacknin J (2001). Smart Medicine for Your Skin: A Comprehensive Guide to Understanding Conventional and Alternative Therapies to Heal Common Skin Problems. Penguin. pp. 271–. ISBN 978-1-58333-098-2. Archived from the original on 2017-11-05.

- Ooi ET, Tidman MJ (February 2014). "Improving the management of seborrhoeic dermatitis". The Practitioner. 258 (1768): 23–6, 3. PMID 24689165.

- Kostović, K.; Lipozencić, J. (2004). "Skin diseases in alcoholics". Acta Dermatovenerologica Croatica. 12 (3): 181–190. PMID 15369644.