Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, or the Second Arab–Israeli war,[15][16][17] also called the Tripartite Aggression (Arabic: العدوان الثلاثي, romanized: Al-ʿUdwān aṯ-Ṯulāṯiyy) in the Arab world[18] and the Sinai War in Israel,[19] was an invasion of Egypt in late 1956 by Israel, followed by the United Kingdom and France. The aims were to regain control of the Suez Canal for the Western powers and to remove Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser, who had just swiftly[20] nationalised the foreign-owned Suez Canal Company, which administered the canal.[21] After the fighting had started, political pressure from the United States, the Soviet Union and the United Nations led to a withdrawal by the three invaders. The episode humiliated the United Kingdom and France and strengthened Nasser.[22][23][24]

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cold War and the Arab–Israeli conflict | |||||||

Damaged Egyptian vehicles | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| |||||||

On 26 July 1956, Nasser nationalised the Suez Canal Company, which prior to that was owned primarily by British and French shareholders. On 29 October, Israel invaded the Egyptian Sinai. Britain and France issued a joint ultimatum to cease fire, which was ignored. On 5 November, Britain and France landed paratroopers along the Suez Canal. Before the Egyptian forces were defeated, they had blocked the canal to all shipping by sinking 40 ships in the canal. It later became clear that Israel, France and Britain had conspired to plan the invasion. The three allies had attained a number of their military objectives, but the canal was useless. Heavy political pressure from the United States and the USSR led to a withdrawal. U.S. president Dwight D. Eisenhower had strongly warned Britain not to invade; he threatened serious damage to the British financial system by selling the U.S. government's pound sterling bonds. Historians conclude the crisis "signified the end of Great Britain's role as one of the world's major powers".[25][26][27]

The Suez Canal was closed from October 1956 until March 1957. Israel fulfilled some of its objectives, such as attaining freedom of navigation through the Straits of Tiran, which Egypt had blocked to Israeli shipping since 1948–1950.[28][29]

As a result of the conflict, the United Nations created the UNEF Peacekeepers to police the Egyptian–Israeli border, British prime minister Anthony Eden resigned, Canadian external affairs minister Lester Pearson won the Nobel Peace Prize, and the USSR may have been emboldened to invade Hungary.[30][31]

Background

History of the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal was opened in 1869, after ten years of work financed by the French and Egyptian governments.[32] The canal was operated by the Universal Company of the Suez Maritime Canal, an Egyptian-chartered company; the area surrounding the canal remained sovereign Egyptian territory and the only land-bridge between Africa and Asia.

The canal instantly became strategically important, as it provided the shortest ocean link between the Mediterranean Sea and the Indian Ocean. The canal eased commerce for trading nations and particularly helped European colonial powers to gain and govern their colonies.

In 1875, as a result of debt and financial crisis, Egypt was forced to sell its shares in the canal operating company to the British government of Benjamin Disraeli. They were willing buyers and obtained a 44% share in the Suez Canal Company for £4 million (£472 million in 2020). This maintained the majority shareholdings of the mostly-French private investors. With the 1882 invasion and occupation of Egypt, the UK took de facto control of the country as well as the canal proper, its finances and operations. The 1888 Convention of Constantinople declared the canal a neutral zone under British protection.[33] In ratifying it, the Ottoman Empire agreed to permit international shipping to pass freely through the canal, in time of war and peace.[34] The Convention came into force in 1904, the same year as the Entente cordiale between Britain and France.

Despite this convention, the strategic importance of the Suez Canal and its control were proven during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905, after Japan and Britain entered into a separate bilateral agreement. Following the Japanese surprise attack on the Russian Pacific Fleet based at Port Arthur, the Russians sent reinforcements from their fleet in the Baltic Sea. The British denied the Russian Baltic Fleet use of the canal after the Dogger Bank incident and forced it to steam around the Cape of Good Hope in Africa, giving the Imperial Japanese Armed Forces time to consolidate their position in East Asia.

The importance of the canal as a strategic intersection was again apparent during the First World War, when Britain and France closed the canal to non-Allied shipping. The attempt by the German-led Ottoman Fourth Army to storm the canal in February 1915 led the British to commit 100,000 troops to the defence of Egypt for the rest of the war.[35]

Oil

The canal continued to be strategically important after the Second World War as a conduit for the shipment of oil.[36] Petroleum business historian Daniel Yergin wrote of the period: "In 1948, the canal abruptly lost its traditional rationale. ... [British] control over the canal could no longer be preserved on grounds that it was critical to the defence either of India or of an empire that was being liquidated. And yet, at exactly the same moment, the canal was gaining a new role—as the highway not of empire, but of oil. ... By 1955, petroleum accounted for half of the canal's traffic, and, in turn, two thirds of Europe's oil passed through it".[37]

At the time, Western Europe imported two million barrels per day from the Middle East, 1,200,000 by tanker through the canal, and another 800,000 via pipeline from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean, where tankers received it. The US imported another 300,000 barrels daily from the Middle East.[38] Though pipelines linked the oil fields of the Kingdom of Iraq and the Persian Gulf states to the Mediterranean, these routes were prone to suffer from instability, which led British leaders to prefer to use the sea route through the Suez Canal.[36] As it was, the rise of super-tankers for shipping Middle East oil to Europe, which were too big to use the Suez Canal, meant that British policy-makers greatly overestimated the importance of the canal.[36] By 2000, only 8 percent of the imported oil in Britain arrived via the Suez canal with the rest coming via the Cape route.[36]

In August 1956 the Royal Institute of International Affairs published a report titled "Britain and the Suez Canal" revealing government perception of the Suez area. It reiterates several times the strategic necessity of the Suez Canal to the United Kingdom, including the need to meet military obligations under the Manila Pact in the Far East and the Baghdad Pact in Iraq, Iran, or Pakistan. The report also points out that the canal had been used in wartime to transport materiel and personnel from and to the UK's close allies in Australia and New Zealand, and might be vital for such purposes in future. The report also cites the amount of material and oil that passes through the canal to the United Kingdom, and the economic consequences of the canal being put out of commission, concluding:

The possibility of the Canal being closed to troopships makes the question of the control and regime of the Canal as important to Britain today as it ever was.[39]

After 1945

In the aftermath of the Second World War, Britain's military strength was spread throughout the region, including the vast military complex at Suez with a garrison of some 80,000, making it one of the largest military installations in the world. The Suez base was considered an important part of Britain's strategic position in the Middle East; however, it became a source of growing tension in Anglo-Egyptian relations.[40]

Egypt's post-war domestic politics were experiencing a radical change, prompted in no small part by economic instability, inflation, and unemployment. Unrest began to manifest itself in the growth of radical political groups, such as the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, and an increasingly hostile attitude towards Britain and its presence in the country. Added to this anti-British fervour was the role Britain had played in the creation of Israel.[40]

In October 1951, the Egyptian government unilaterally abrogated the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936, the terms of which granted Britain a lease on the Suez base for 20 more years.[41] Britain refused to withdraw from Suez, relying upon its treaty rights, as well as the presence of the Suez garrison. The price of such a course of action was a steady escalation in violent hostility towards Britain and British troops in Egypt, which the Egyptian authorities did little to curb.

On 25 January 1952, British forces attempted to disarm a troublesome auxiliary police force barracks in Ismailia, resulting in the deaths of 41 Egyptians.[42] This in turn led to anti-Western riots in Cairo resulting in heavy damage to property and the deaths of several foreigners, including 11 British citizens.[42] This proved to be a catalyst for the removal of the Egyptian monarchy. On 23 July 1952 a military coup by the Egyptian nationalist 'Free Officers Movement'—led by Muhammad Neguib and future Egyptian President Gamal Abdul Nasser—overthrew King Farouk and established an Egyptian republic.

Post–Egyptian Revolution period

In the 1950s, the Middle East was dominated by four interlinked conflicts:

- the Cold War, the geopolitical battle for influence between the United States and the Soviet Union;

- the Arab Cold War, the race between different Arab states for the leadership of the Arab world;[43]

- the anti-colonial struggle of Arab nationalists against the two remaining imperial powers, Britain and France, in particular the Algerian War;[44]

- and the Arab–Israeli conflict, the political and military conflict between the Arab countries and Israel.

Egypt and Britain

Britain's desire to mend Anglo-Egyptian relations in the wake of the coup saw the country strive for rapprochement throughout 1953 and 1954. Part of this process was the agreement, in 1953, to terminate British rule in Sudan by 1956 in return for Cairo's abandoning of its claim to suzerainty over the Nile Valley region. In October 1954, Britain and Egypt concluded the Anglo-Egyptian Agreement of 1954 on the phased evacuation of British Armed Forces troops from the Suez base, the terms of which agreed to withdrawal of all troops within 20 months, maintenance of the base to be continued, and for Britain to hold the right to return for seven years.[45] The Suez Canal Company was not due to revert to the Egyptian government until 16 November 1968 under the terms of the treaty.[46]

Britain's close relationship with the two Hashemite kingdoms of Iraq and Jordan were of particular concern to Nasser. In particular, Iraq's increasingly amicable relations with Britain were a threat to Nasser's desire to see Egypt as head of the Arab world. The creation of the Baghdad Pact in 1955 seemed to confirm Nasser's fears that Britain was attempting to draw the Eastern Arab World into a bloc centred upon Iraq, and sympathetic to Britain.[47] Nasser's response was a series of challenges to British influence in the region that would culminate in the Suez Crisis.

Egypt and the Arab leadership

In regard to the Arab leadership, particularly venomous was the feud between Nasser and the Prime Minister of Iraq, Nuri al-Said, for Arab leadership, with the Cairo-based Voice of the Arabs radio station regularly calling for the overthrow of the government in Baghdad.[43] The most important factors that drove Egyptian foreign policy in this period was on the one hand, a determination to see the entire Middle East as Egypt's rightful sphere of influence, and on the other, a tendency on the part of Nasser to fortify his pan-Arabist and nationalist credibility by seeking to oppose any and all Western security initiatives in the Near East.[43]

Despite the establishment of such an agreement with the British, Nasser's position remained tenuous. The loss of Egypt's claim to Sudan, coupled with the continued presence of Britain at Suez for a further two years, led to domestic unrest including an assassination attempt against him in October 1954. The tenuous nature of Nasser's rule caused him to believe that neither his regime, nor Egypt's independence would be safe until Egypt had established itself as head of the Arab world.[48] This would manifest itself in the challenging of British Middle Eastern interests throughout 1955.

US and a defence treaty against the Soviet threat

The United States, while attempting to erect an alliance in the form of a Middle East Defense Organization to keep the Soviet Union out of the Near East, tried to woo Nasser into this alliance.[49] The central problem for American policy in the Middle East was that this region was perceived as strategically important due to its oil, but the United States, weighed down by defence commitments in Europe and the Far East, lacked sufficient troops to resist a Soviet invasion of the Middle East.[50] In 1952, General Omar Bradley of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff declared at a planning session about what to do in the event of a Soviet invasion of the Near East: "Where will the staff come from? It will take a lot of stuff to do a job there".[50]

As a consequence, American diplomats favoured the creation of a NATO-type organisation in the Near East to provide the necessary military power to deter the Soviets from invading the region.[50] The Eisenhower administration, even more than the Truman administration, saw the Near East as a huge gap into which Soviet influence could be projected, and accordingly required an American-supported security system.[51] American diplomat Raymond Hare later recalled:

It's hard to put ourselves back in this period. There was really a definite fear of hostilities, of an active Russian occupation of the Middle East physically, and you practically hear the Russian boots clumping down over the hot desert sands.[52]

The projected Middle East Defense Organization (MEDO) was to be centered on Egypt.[52] A United States National Security Council directive of March 1953 called Egypt the "key" to the Near East and advised that Washington "should develop Egypt as a point of strength".[51]

A major dilemma for American policy was that the two strongest powers in the Near East, Britain and France, were also the nations whose influence many local nationalists most resented.[50] From 1953 onwards, American diplomacy had attempted unsuccessfully to persuade the powers involved in the Near East, both local and imperial, to set aside their differences and unite against the Soviet Union.[53] The Americans took the view that, just as fear of the Soviet Union had helped to end the historic Franco-German enmity, so too could anti-Communism end the more recent Arab–Israeli dispute. It was a source of constant puzzlement to American officials in the 1950s that the Arab states and the Israelis had seemed to have more interest in fighting each other rather than uniting against the Soviet Union. After his visit to the Middle East in May 1953 to drum up support for MEDO, the Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles found much to his astonishment that the Arab states were "more fearful of Zionism than of the Communists".[54]

The policy of the United States was colored by considerable uncertainty as to whom to befriend in the Near East. American policy was torn between a desire to maintain good relations with NATO allies such as Britain and France who were also major colonial powers, and a desire to align Third World nationalists with the Free World camp.[55] Though it would be entirely false to describe the coup deposing King Farouk in July 1952 as a Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) coup, Nasser and his Society of Free Officers were nonetheless in close contact with CIA operatives led by Miles Copeland beforehand (Nasser maintained links with any and all potential allies from the Egyptian Communist Party on the left to the Muslim Brotherhood on the right).[56]

Nasser's friendship with certain CIA officers in Cairo led Washington to vastly overestimate its influence in Egypt.[52] That Nasser was close to CIA officers led the Americans for a time to view Nasser as a CIA "asset".[57] In turn, the British who were aware of Nasser's CIA ties deeply resented this relationship, which they viewed as an American attempt to push them out of Egypt.[57] The principal reason for Nasser's courting of the CIA before the July Revolution of 1952 was his hope that the Americans would act as a restraining influence on the British should Britain decide on intervention to put an end to the revolution (until Egypt renounced it in 1951, the 1936 Anglo-Egyptian treaty allowed Britain the right of intervention against all foreign and domestic threats).[58] In turn, many American officials, such as Ambassador Jefferson Caffery, saw the continued British military presence in Egypt as anachronistic, and viewed the Revolutionary Command Council (as Nasser called his government after the coup) in a highly favourable light.[59]

Caffery was consistently very positive about Nasser in his reports to Washington right up until his departure from Cairo in 1955. The regime of King Farouk was viewed in Washington as weak, corrupt, unstable, and anti-American, so the Free Officers' July coup was welcomed by the United States.[52] As it was, Nasser's contacts with the CIA were not necessary to prevent British intervention against the July coup as Anglo-Egyptian relations had deteriorated so badly in 1951–52 that the British viewed any Egyptian government not headed by King Farouk as a huge improvement.[60] In May 1953, during a meeting with Secretary Dulles, who asked Egypt to join an anti-Soviet alliance, Nasser responded by saying that the Soviet Union has

never occupied our territory ... but the British have been here for seventy years. How can I go to my people and tell them I am disregarding a killer with a pistol sixty miles from me at the Suez Canal to worry about somebody who is holding a knife a thousand miles away?[49]

Dulles informed Nasser of his belief that the Soviet Union was seeking world conquest, that the principal danger to the Near East came from the Kremlin, and urged Nasser to set aside his differences with Britain to focus on countering the Soviet Union.[49] In this spirit, Dulles suggested that Nasser negotiate a deal that would see Egypt assume sovereignty over the canal zone base, but then allow the British to have "technical control" in the same way that Ford auto company provided parts and training to its Egyptian dealers.[49]

Nasser did not share Dulles's fear of the Soviet Union taking over the Middle East, and insisted quite vehemently that he wanted to see the total end of all British influence not only in Egypt, but all the Middle East.[49] The CIA offered Nasser a $3 million bribe if he would join the proposed Middle East Defense Organization; Nasser took the money, but then refused to join.[61] At most, Nasser made it clear to the Americans that he wanted an Egyptian-dominated Arab League to be the principal defence organisation in the Near East, which might be informally associated with the United States.

After he returned to Washington, Dulles advised Eisenhower that the Arab states believed "the United States will back the new state of Israel in aggressive expansion. Our basic political problem ... is to improve the Moslem states' attitudes towards Western democracies because our prestige in that area had been in constant decline ever since the war".[54] The immediate consequence was a new policy of "even-handedness" where the United States very publicly sided with the Arab states in several disputes with Israel in 1953–54.[62] Moreover, Dulles did not share any sentimental regard for the Anglo-American "special relationship", which led the Americans to lean towards the Egyptian side in the Anglo-Egyptian disputes.[63] During the extremely difficult negotiations over the British evacuation of the Suez Canal base in 1954–55, the Americans generally supported Egypt, though at the same time trying hard to limit the extent of the damage that this might cause to Anglo-American relations.[64]

In the same report of May 1953 to President Dwight D. Eisenhower calling for "even-handedness", Dulles stated that the Egyptians were not interested in joining the proposed MEDO; that the Arabs were more interested in their disputes with the British, the French, the Israelis and each other than in standing against the Soviets; and that the "Northern Tier" states of Turkey, Iran and Pakistan were more useful as allies at present than Egypt.[51] Accordingly, the best American policy towards Egypt was to work towards Arab–Israeli peace and the settlement of the Anglo-Egyptian dispute over the British Suez Canal base as the best way of securing Egypt's ultimate adhesion to an American sponsored alliance centered on the "Northern Tier" states.[65]

The "Northern Tier" alliance was achieved in early 1955 with the creation of the Baghdad Pact comprising Pakistan, Iran, Turkey, Iraq and the United Kingdom.[66] The presence of the last two states was due to the British desire to continue to maintain influence in the Middle East, and Nuri Said's wish to associate his country with the West as the best way of counterbalancing the increasing aggressive Egyptian claims to regional predominance.[66] The conclusion of the Baghdad Pact occurred almost simultaneously with a dramatic Israeli reprisal operation on the Gaza Strip on 28 February 1955 in retaliation for Palestinian fedayeen raids into Israel, during which the Israeli Unit 101 commanded by Ariel Sharon did some damage to Egyptian Army forces.[66]

The close occurrence of the two events was mistakenly interpreted by Nasser as part of coordinated Western effort to push him into joining the Baghdad Pact.[67] The signing of the Baghdad Pact and the Gaza raid marked the beginning of the end of Nasser's once good relations with the Americans.[67] In particular, Nasser saw Iraq's participation in the Baghdad Pact as a Western attempt to promote his archenemy Nuri al-Said as an alternative leader of the Arab world.[68]

Nasser and the Soviet bloc

Instead of siding with either superpower, Nasser took the role of the spoiler and tried to play off the superpowers in order to have them compete with each other in attempts to buy his friendship.[69]

Under the new leadership of Nikita Khrushchev, the Soviet Union was making a major effort to win influence in the so-called Third World.[70] As part of the diplomatic offensive, Khrushchev had abandoned Moscow's traditional line of treating all non-communists as enemies and adopted a new tactic of befriending so-called "non-aligned" nations, which often were led by leaders who were non-Communists, but in varying ways and degrees were hostile towards the West.[70] Khrushchev had realised that by treating non-communists as being the same thing as being anti-communist, Moscow had needlessly alienated many potential friends over the years in the Third World.[70] Under the banner of anti-imperialism, Khrushchev made it clear that the Soviet Union would provide arms to any left-wing government in the Third World as a way of undercutting Western influence.[71]

Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai met Nasser at the 1955 Bandung Conference and was impressed by him. Zhou recommended that Khrushchev treat Nasser as a potential ally.[70] Zhou described Nasser to Khrushchev as a young nationalist who, though no Communist, could if used correctly do much damage to Western interests in the Middle East. Marshal Josip Broz Tito of Yugoslavia, who also came to know Nasser at the Bandung Conference told Khrushchev in a 1955 meeting that "Nasser was a young man without much political experience, but if we give him the benefit of the doubt, we might be able to exert a beneficial influence on him, both for the sake of the Communist movement, and ... the Egyptian people".[70] Traditionally, most of the equipment in the Egyptian military had come from Britain, but Nasser's desire to break British influence in Egypt meant that he was desperate to find a new source of weapons to replace Britain. Nasser had first broached the subject of buying weapons from the Soviet Union in 1954.[72]

Nasser and arms purchases

Most of all, Nasser wanted the United States to supply arms on a generous scale to Egypt.[66] Nasser refused to promise that any U.S. arms he might buy would not be used against Israel, and rejected out of hand the American demand for a Military Advisory Group to be sent to Egypt as part of the price of arms sales.[73]

Nasser's first choice for buying weapons was the United States. However his frequent anti-Zionist speeches and sponsorship of the Palestinian fedayeen, who made frequent raids into Israel, rendered it difficult for the Eisenhower administration to get the approval of Congress necessary to sell weapons to Egypt. American public opinion was deeply hostile towards selling arms to Egypt that might be used against Israel. Moreover, Eisenhower feared doing so could trigger a Middle Eastern arms race.[73] Eisenhower very much valued the Tripartite Declaration as a way of keeping peace in the Near East. In 1950, in order to limit the extent that the Arabs and the Israelis could engage in an arms race, the three nations which dominated the arms trade in the non-Communist world, namely the United States, the United Kingdom and France had signed the Tripartite Declaration, where they had committed themselves to limiting how much arms they could sell in the Near East, and also to ensuring that any arms sales to one side was matched by arms sales of equal quantity and quality to the other.[74] Eisenhower viewed the Tripartite Declaration, which sharply restricted how many arms Egypt could buy in the West, as one of the key elements in keeping the peace between Israel and the Arabs, and believed that setting off an arms race would inevitably lead to a new war.

The Egyptians made continuous attempts to purchase heavy arms from Czechoslovakia years before the 1955 deal.[75]

Nasser had let it be known, in 1954–55, that he was considering buying weapons from the Soviet Union, and thus coming under Soviet influence, as a way of pressuring the Americans into selling him the arms he desired.[70] Khrushchev, who very much wanted to win the Soviet Union influence in the Middle East, was more than ready to arm Egypt if the Americans proved unwilling.[70] During secret talks with the Soviets in 1955, Nasser's demands for weapons were more than amply satisfied as the Soviet Union had not signed the Tripartite Declaration.[76] The news in September 1955 of the Egyptian purchase of a huge quantity of Soviet arms via Czechoslovakia was greeted with shock and rage in the West, where this was seen as a major increase in Soviet influence in the Near East.[77] In Britain, the increase of Soviet influence in the Near East was seen as an ominous development that threatened to put an end to British influence in the oil-rich region.[78]

France and the Egyptian support for the Algerian rebellion

Over the same period, the French Premier Guy Mollet, was facing an increasingly serious rebellion in Algeria, where the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN) rebels were being verbally supported by Egypt via transmissions of the Voice of the Arabs radio, financially supported with Suez Canal revenue[79] and clandestinely owned Egyptian ships were shipping arms to the FLN.[80] Mollet came to perceive Nasser as a major threat.[81] During a visit to London in March 1956, Mollet told Eden his country was faced with an Islamic threat to the very soul of France supported by the Soviet Union.[81] Mollet stated: "All this is in the works of Nasser, just as Hitler's policy was written down in Mein Kampf. Nasser has the ambition to recreate the conquests of Islam. But his present position is largely due to the policy of the West in building up and flattering him".[81]

In a May 1956 gathering of French veterans, Louis Mangin spoke in place of the unavailable Minister of Defence and gave a violently anti-Nasser speech, which compared the Egyptian leader to Hitler. He accused Nasser of plotting to rule the entire Middle East and of seeking to annex Algeria, whose "people live in community with France".[82] Mangin urged France to stand up to Nasser, and being a strong friend of Israel, urged an alliance with that nation against Egypt.[83]

Egypt and Israel

Prior to 1955, Nasser had pursued efforts to reach peace with Israel and had worked to prevent cross-border Palestinian attacks.[84] In 1955, however, Unit 101, an Israeli unit under Ariel Sharon, conducted an unprovoked raid on the Egyptian Army headquarters in Gaza; in response, Nasser began allowing raids into Israel by the fedayeen.[84] The raids triggered a series of Israeli reprisal operations, which ultimately contributed to the Suez Crisis.[85][84]

Franco-Israeli alliance emerges

Starting in 1949 owing to shared nuclear research, France and Israel started to move towards an alliance.[86] Following the outbreak of the Algerian War in late 1954, France began to ship more and more arms to Israel.[87] In November 1954, the Director-General of Israel's Ministry of Defense Shimon Peres visited Paris, where he was received by the French Defense Minister Marie-Pierre Kœnig, who told him that France would sell Israel any weapons it wanted to buy.[88] By early 1955, France was shipping large amounts of weapons to Israel.[88] In April 1956, following another visit to Paris by Peres, France agreed to totally disregard the Tripartite Declaration, and supply even more weapons to Israel.[89] During the same visit, Peres informed the French that Israel had decided upon war with Egypt in 1956.[90] Peres claimed that Nasser was a genocidal maniac intent upon not only destroying Israel, but also exterminating its people, and as such, Israel wanted a war before Egypt received even more Soviet weapons, and there was still a possibility of victory for the Jewish state.[90] Peres asked for the French, who had emerged as Israel's closest ally by this point, to give Israel all the help they could give in the coming war.

Frustration of British aims

Throughout 1955 and 1956, Nasser pursued a number of policies that would frustrate British aims throughout the Middle East, and result in increasing hostility between Britain and Egypt. Nasser saw Iraq's inclusion in the Baghdad Pact as indicating that the United States and Britain had sided with his much hated archenemy Nuri as-Said's efforts to be the leader of the Arab world, and much of the motivation for Nasser's turn to an active anti-Western policy starting in 1955 was due to his displeasure with the Baghdad Pact.[91] For Nasser, attendance at such events as the Bandung conference in April 1955 served as both the means of striking a posture as a global leader, and of playing hard to get in his talks with the Americans, especially his demand that the United States sell him vast quantities of arms.[92]

Nasser "played on the widespread suspicion that any Western defence pact was merely veiled colonialism and that Arab disunity and weakness—especially in the struggle with Israel—was a consequence of British machinations."[47] He also began to align Egypt with the kingdom of Saudi Arabia—whose rulers were hereditary enemies of the Hashemites—in an effort to frustrate British efforts to draw Syria, Jordan and Lebanon into the orbit of the Baghdad Pact. Nasser struck a further blow against Britain by negotiating an arms deal with communist Czechoslovakia in September 1955[93] thereby ending Egypt's reliance on Western arms. Later, other members of the Warsaw Pact also sold arms to Egypt and Syria. In practice, all sales from the Eastern Bloc were authorised by the Soviet Union, as an attempt to increase Soviet influence over the Middle East. This caused tensions in the United States because Warsaw Pact nations now had a strong presence in the region.

Nasser and 1956 events

Nasser and Jordan

Nasser frustrated British attempts to draw Jordan into the pact by sponsoring demonstrations in Amman, leading King Hussein of Jordan in the Arabization of the Jordanian Army command to dismiss the British commander of the Arab Legion, Sir John Bagot Glubb (known to the Arabs as Glubb Pasha) in March 1956, throwing Britain's Middle Eastern security policy into chaos.[94] After one round of bloody rioting in December 1955 and another in March 1956 against Jordan joining the Baghdad Pact, both instigated by Cairo-based Voice of the Arabs radio station, Hussein believed his throne was in danger.[95] In private, Hussein assured the British that he was still committed to continuing the traditional Hashemite alliance with Britain, and that his sacking of Glubb Pasha and all the other British officers in the Arab Legion were just gestures to appease the rioters.

Nasser and Britain

British Prime Minister Anthony Eden was especially upset at the sacking of Glubb Pasha, and as one British politician recalled:

For Eden ... this was the last straw.... This reverse, he insisted was Nasser's doing.... Nasser was our Enemy No. 1 in the Middle East and he would not rest until he destroyed all our friends and eliminated the last vestiges of our influence.... Nasser must therefore be ... destroyed.[96]

After the sacking of Glubb Pasha, which he saw as a grievous blow to British influence, Eden became consumed with an obsessional hatred for Nasser, and from March 1956 onwards, was in private committed to the overthrow of Nasser.[97] The American historian Donald Neff wrote that Eden's often hysterical and overwrought views towards Nasser almost certainly reflected the influence of the amphetamines to which Eden had become addicted following a botched operation in 1953 together with the related effects of sustained sleep deprivation (Eden slept on average about 5 hours per night in early 1956).[98]

Increasingly Nasser came to be viewed in British circles—and in particular by Eden—as a dictator, akin to Benito Mussolini. In the build-up to the crisis, the Labour leader Hugh Gaitskell and the left-leaning tabloid newspaper The Mirror made the first comparison between Nasser and Mussolini. Anglo-Egyptian relations would continue on their downward spiral.

Britain was eager to tame Nasser and looked towards the United States for support. However, Eisenhower strongly opposed British-French military action.[99] America's closest Arab ally, Saudi Arabia, was just as fundamentally opposed to the Hashemite-dominated Baghdad Pact as Egypt, and the U.S. was keen to increase its own influence in the region.[100] The failure of the Baghdad Pact aided such a goal by reducing Britain's dominance over the region. "Great Britain would have preferred to overthrow Nasser; America, however uncomfortable with the 'Czech arms deal', thought it wiser to propitiate him."[101]

The United States and the Aswan High Dam

On 16 May 1956, Nasser officially recognized the People's Republic of China, which angered the U.S. and Secretary Dulles, a sponsor of the Republic of China.[94] This move, coupled with the impression that the project was beyond Egypt's economic capabilities, caused Eisenhower to withdraw all American financial aid for the Aswan Dam project on 19 July.[94]

The Eisenhower administration believed that if Nasser were able to secure Soviet economic support for the high dam, that would be beyond the capacity of the Soviet Union to support, and in turn would strain Soviet-Egyptian relations.[102] Eisenhower wrote in March 1956 that "If Egypt finds herself thus isolated from the rest of the Arab world, and with no ally in sight except Soviet Russia, she would very quickly get sick of the prospect and would join us in the search for a just and decent peace in the region".[102] Dulles told his brother, CIA director Allen Dulles, "If they [the Soviets] do make this offer we can make a lot of use of it in propaganda within the satellite bloc. You don't get bread because you are being squeezed to build a dam".[102]

Finally, the Eisenhower administration had become very annoyed at Nasser's efforts to play the United States off against the Soviet Union, and refused to finance the Aswan high dam. As early as September 1955, when Nasser announced the purchase of the Soviet military equipment via Czechoslovakia, Dulles had written that competing for Nasser's favor was probably going to be "an expensive process", one that Dulles wanted to avoid as much as possible.[103]

1956 American peace initiative

In January 1956, to end the incipient arms race in the Middle East (set off by the Soviet Union selling Egypt arms on a scale unlimited by the Tripartite Declaration and with France doing likewise with Israel), which he saw as opening the Near East to Soviet influence, Eisenhower launched a major effort to make peace between Egypt and Israel. Eisenhower sent out his close friend Robert B. Anderson to serve as a secret envoy who would permanently end the Arab–Israeli dispute.[104] During his meetings with Nasser, Anderson offered large quantities of American aid in exchange for a peace treaty with Israel. Nasser demanded the return of Palestinian refugees to Israel, wanted to annex the southern half of Israel and rejected direct talks with Israel.[105][106] Given Nasser's territorial and refugee-related demands, the Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion suspected that Nasser was not interested in a settlement. Still, he proposed direct negotiations with Egypt in any level.[105][107]

A second round of secret diplomacy by Anderson in February 1956 was equally unsuccessful.[108] Nasser sometimes suggested during his talks with Anderson that he was interested in peace with Israel if only the Americans would supply him with unlimited quantities of military and economic aid. In case of Israeli acceptance to the Palestinian right of return and to Egypt annexing the southern half of Israel, Egypt would not accept a peace settlement. The United States or the United Nations would have to present the Israeli acceptance to all Arabs as a basis for peace settlements.[109] It is not clear if Nasser was sincerely interested in peace, or just merely saying what the Americans wanted to hear in the hope of obtaining American funding for the Aswan high dam and American weapons. The truth will likely never be known as Nasser was an intensely secretive man, who managed to hide his true opinions on most issues from both contemporaries and historians.[110] However, the British historian P. J. Vatikitos noted that Nasser's determination to promote Egypt as the world's foremost anti-Zionist state as a way of reinforcing his claim to Arab leadership meant that peace was unlikely.[111]

Hasan Afif El-Hasan says that in 1955–1956 the Americans proposed to Nasser that he solve the Arab–Israeli conflict peacefully in exchange for American finance of the High Dam on the Nile river, but Nasser rejected the offer because it would mean siding with the West (as opposed to remaining neutral) in the Cold War. Since the alternative to a peace agreement was a war with unpredictable consequences, Nasser's refusal to accept the proposal was irrational, according to el-Hasan.[112]

Canal nationalisation

Nasser's response was the nationalisation of the Suez Canal. On 26 July, in a speech in Alexandria, Nasser gave a riposte to Dulles. During his speech he deliberately pronounced the name of Ferdinand de Lesseps, the builder of the canal, a code-word for Egyptian forces to seize control of the canal and implement its nationalisation.[113] He announced that the Nationalization Law had been published, that all assets of the Suez Canal Company had been frozen, and that stockholders would be paid the price of their shares according to the day's closing price on the Paris Stock Exchange.[114] That same day, Egypt closed the canal to Israeli shipping.[115] Egypt also closed the Straits of Tiran to Israeli shipping, and blockaded the Gulf of Aqaba, in contravention of the Constantinople Convention of 1888. Many argued that this was also a violation of the 1949 Armistice Agreements.[116][117]

According to the Egyptian historian Abd al-Azim Ramadan, the events leading up to the nationalisation of the Suez Canal Company, as well as other events during Nasser's rule, showed Nasser to be far from a rational, responsible leader. Ramadan notes Nasser's decision to nationalise the Suez Canal without political consultation as an example of his predilection for solitary decision-making.[118]

British response

The nationalisation surprised Britain and its Commonwealth. There had been no discussion of the canal at the Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conference in London in late June and early July.[119]: 7–8 Egypt's action, however, threatened British economic and military interests in the region. Prime Minister Eden was under immense domestic pressure from Conservative MPs who drew direct comparisons between the events of 1956 and those of the Munich Agreement in 1938. Since the U.S. government did not support the British protests, the British government decided in favour of military intervention against Egypt to avoid the complete collapse of British prestige in the region.[120]

Eden was hosting a dinner for King Feisal II of Iraq and his Prime Minister, Nuri es-Said, when he learned the canal had been nationalised. They both unequivocally advised Eden to "hit Nasser hard, hit him soon, and hit him by yourself" – a stance shared by the vast majority of the British people in subsequent weeks. "There is a lot of humbug about Suez," Guy Millard, one of Eden's private secretaries, later recorded. "People forget that the policy at the time was extremely popular." Leader of the Opposition Hugh Gaitskell was also at the dinner. He immediately agreed that military action might be inevitable, but warned Eden would have to keep the Americans closely informed.[121] After a session of the House of Commons expressed anger against the Egyptian action on 27 July, Eden justifiably believed that Parliament would support him; Gaitskell spoke for his party when he called the nationalisation a "high-handed and totally unjustifiable step".[119]: 8–9 When Eden made a ministerial broadcast on the nationalisation, Labour declined its right to reply.[122]

However, in the days that followed, Gaitskell's support became more cautious. On 2 August he said of Nasser's behaviour, "It is all very familiar. It is exactly the same that we encountered from Mussolini and Hitler in those years before the war". He cautioned Eden, however, that "[w]e must not, therefore, allow ourselves to get into a position where we might be denounced in the Security Council as aggressors, or where the majority of the Assembly was against us". He had earlier warned Eden that Labour might not support Britain acting alone against Egypt.[119]: 8–9 In two letters to Eden sent on 3 and 10 August 1956, Gaitskell condemned Nasser but again warned that he would not support any action that violated the United Nations Charter.[123] In his letter of 10 August, Gaitskell wrote:

Lest there should be any doubt in your mind about my personal attitude, let me say that I could not regard an armed attack on Egypt by ourselves and the French as justified by anything which Nasser has done so far or as consistent with the Charter of the United Nations. Nor, in my opinion, would such an attack be justified in order to impose a system of international control over the Canal-desirable though this is. If, of course, the whole matter were to be taken to the United Nations and if Egypt were to be condemned by them as aggressors, then, of course, the position would be different. And if further action which amounted to obvious aggression by Egypt were taken by Nasser, then again it would be different. So far what Nasser has done amounts to a threat, a grave threat to us and to others, which certainly cannot be ignored; but it is only a threat, not in my opinion justifying retaliation by war.[124]

Two dozen Labour MPs issued a statement on 8 August stating that forcing Nasser to denationalise the canal against Egypt's wishes would violate the UN charter. Other opposition politicians were less conditional in their support. Former Labour Foreign Minister Herbert Morrison hinted that he would support unilateral action by the government.[119]: 9–10 Jo Grimond, who became Leader of the Liberal Party that November, thought if Nasser went unchallenged the whole Middle East would go his way.[120]

In Britain, the nationalisation was perceived as a direct threat to British interests. In a letter to the British Ambassador on 10 September 1956, Sir Ivone Kirkpatrick, the Permanent Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office wrote:

If we sit back while Nasser consolidates his position and gradually acquires control of the oil-bearing countries, he can and is, according to our information, resolved to wreck us. If Middle Eastern oil is denied to us for a year or two, our gold reserves will disappear. If our gold reserves disappear, the sterling area disintegrates. If the sterling area disintegrates and we have no reserves, we shall not be able to maintain a force in Germany, or indeed, anywhere else. I doubt whether we shall be able to pay for the bare minimum necessary for our defence. And a country that cannot provide for its defence is finished.[125]

Direct military intervention, however, ran the risk of angering Washington and damaging Anglo-Arab relations. As a result, the British government concluded a secret military pact with France and Israel that was aimed at regaining control over the Suez Canal.

French response

The French Prime Minister Guy Mollet, outraged by Nasser's move, determined that Nasser would not get his way.[126] French public opinion very much supported Mollet, and apart from the French Communist Party, all of the criticism of his government came from the right, who very publicly doubted that a socialist like Mollet had the guts to go to war with Nasser.[126] During an interview with publisher Henry Luce, Mollet held up a copy of Nasser's book The Philosophy of the Revolution and said: "This is Nasser's Mein Kampf. If we're too stupid not to read it, understand it and draw the obvious conclusions, then so much the worse for us."[127]

On 29 July 1956, the French Cabinet decided upon military action against Egypt in alliance with Israel, and Admiral Nomy of the French Naval General Staff was sent to Britain to inform the leaders of that country of France's decision, and to invite them to co-operate if interested.[127] At the same time, Mollet felt very much offended by what he considered to be the lackadaisical attitude of the Eisenhower administration to the nationalisation of the Suez Canal Company.[128] This was especially the case because earlier in 1956 the Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov had offered the French a deal whereby if Moscow ended its support of the FLN in Algeria, Paris would remain in NATO but become "semi-neutralist" in the Cold War.[128]

Given the way that Algeria (which the French considered an integral part of France) had become engulfed in a spiral of increasing savage violence that French leaders longed to put an end to, the Mollet administration had felt tempted by Molotov's offer, but in the end, Mollet, a firm Atlanticist, had chosen to remain faithful to NATO. In Mollet's view, his fidelity to NATO had earned him the right to expect firm American support against Egypt, and when that support proved not forthcoming, he became even more determined that if the Americans were not willing to do anything about Nasser, then France would act.[128]

Commonwealth response

Among the "White Dominions" of the British Commonwealth, Canada had few ties with the Suez Canal and twice had refused British requests for peacetime military aid in the Middle East. It had little reaction to the seizure before military action. By 1956 the Panama Canal was much more important than Suez to Australia and New Zealand; the following year two experts would write that it "is not vital to the Australian economy". The memory, however, of the two nations fighting in two world wars to protect a canal which many still called their "lifeline" to Britain or "jugular vein", contributed to Australian Prime Minister Robert Menzies and New Zealand Prime Minister Sidney Holland, supporting Britain in the early weeks following the seizure. On 7 August Holland hinted to his parliament that New Zealand might send troops to assist Britain, and received support from the opposition. On 13 August, Menzies, who had travelled to London from the United States after hearing of the nationalisation and became an informal member of the British Cabinet discussing the issue, spoke on the BBC in support of the Eden government's position on the canal. He called the dispute over the canal "a crisis more grave than any since the Second World War ended".[119]: 13–16, 56–58, 84 An elder statesman of the Commonwealth who felt that Nasser's actions threatened trading nations like Australia, he argued publicly that Western powers had built the canal but that Egypt was now seeking to exclude them from a role in its ownership or management.[129][130] South Africa's Johannes Strijdom stated "it is best to keep our heads out of the beehive". His government saw Nasser as an enemy but would benefit economically and geopolitically from a closed canal, and diplomatically from not opposing a nation's right to govern its internal affairs.[119]: 16–18

The "non-white Dominions" saw Egypt's seizing of the canal as an admirable act of anti-imperialism, and Nasser's Arab nationalism as similar to Asian nationalism. Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru was with Nasser when he learned of the Anglo-American withdrawal of aid for the Aswan Dam. As India was a major user of the canal, however, he remained publicly neutral other than warning that any use of force, or threats, could be "disastrous". Suez was also very important to the Dominion of Ceylon's economy, and it was renegotiating defence treaties with Britain, so its government was not as vocal in supporting Egypt as it would have likely been otherwise. Pakistan was also cautious about supporting Egypt given their rivalry as leading Islamic nations, but its government did state that Nasser had the right to nationalise.[119]: 18–24, 79

Western diplomacy

On 1 August 1956, a tripartite meeting was opened at 10 Downing Street between British Foreign Secretary Selwyn Lloyd, U.S. Ambassador Robert D. Murphy and French Foreign Affairs Minister Christian Pineau.[131]

An alliance was soon formed between Eden and Guy Mollet, French Prime Minister, with headquarters in London. General Hugh Stockwell and Admiral Pierre Barjot were appointed as Chief of Staff. Britain sought co-operation with the United States throughout 1956 to deal with what it maintained was a threat of an Israeli attack against Egypt, but to little effect.

Between July and October 1956, unsuccessful initiatives encouraged by the United States were made to reduce the tension that would ultimately lead to war. International conferences were organised to secure agreement on Suez Canal operations but all were ultimately fruitless.

Almost immediately after the nationalisation, Eisenhower suggested to Eden a conference of maritime nations that used the canal. The British preferred to invite the most important countries, but the Americans believed that inviting as many as possible amid maximum publicity would affect world opinion. Invitations went to the eight surviving signatories of the Constantinople Convention and the 16 other largest users of the canal: Australia, Ceylon, Denmark, Egypt, Ethiopia, France, West Germany, Greece, India, Indonesia, Iran, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Pakistan, Portugal, Soviet Union, Spain, Sweden, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and the United States. All except Egypt—which sent an observer, and used India and the Soviet Union to represent its interests—and Greece accepted the invitation, and the 22 nations' representatives met in London from 16 to 23 August.[132][133][119]: 81–89

15 of the nations supported the American-British-French position of international operation of the canal; Pakistan chose its western allies over its sympathy for Egypt's anti-western position despite resulting great domestic controversy. Ceylon, Indonesia, and the Soviet Union supported India's competing proposal—which Nasser had preapproved—of international supervision only. India criticised Egypt's seizure of the canal, but insisted that its ownership and operation now not change. The majority of 18 chose five nations to negotiate with Nasser in Cairo led by Menzies, while their proposal for international operation of the canal would go to the Security Council.[119]: 81–89 [129][133]

Menzies' 7 September official communique to Nasser presented a case for compensation for the Suez Canal Company and the "establishment of principles" for the future use of the canal that would ensure that it would "continue to be an international waterway operated free of politics or national discrimination, and with financial structure so secure and an international confidence so high that an expanding and improving future for the Canal could be guaranteed" and called for a convention to recognise Egyptian sovereignty of the canal, but for the establishment of an international body to run the canal. Nasser saw such measures as a "derogation from Egyptian sovereignty" and rejected Menzies' proposals.[129] Menzies hinted to Nasser that Britain and France might use force to resolve the crisis, but Eisenhower openly opposed the use of force and Menzies left Egypt without success.[130]

Instead of the 18-nation proposal, the United States proposed an association of canal users that would set rules for its operation. 14 of the other nations, not including Pakistan, agreed. Britain, in particular, believed that violation of the association rules would result in military force, but after Eden made a speech to this effect in parliament on 12 September, the US ambassador Dulles insisted "we do not intend to shoot our way through" the canal.[119]: 89–92 The United States worked hard through diplomatic channels to resolve the crisis without resorting to conflict. "The British and French reluctantly agreed to pursue the diplomatic avenue but viewed it as merely an attempt to buy time, during which they continued their military preparations."[134] The British, Washington's closest ally, ignored Eisenhower's pointed warning that the American people would not accept a military solution.[135]

On 25 September 1956 the Chancellor of the Exchequer Harold Macmillan met informally with Eisenhower at the White House. Macmillan misread Eisenhower's determination to avoid war and told Eden that the Americans would not in any way oppose the attempt to topple Nasser.[136] Though Eden had known Eisenhower for years and had many direct contacts with him during the crisis, he also misread the situation. The Americans refused to support any move that could be seen as imperialism or colonialism, seeing the US as the champion of decolonisation. Eisenhower felt the crisis had to be handled peacefully; he told Eden that American public opinion would not support a military solution. Eden and other leading British officials incorrectly believed Nasser's support for Palestinian fedayeen against Israel, as well as his attempts to destabilise pro-western regimes in Iraq and other Arab states, would deter the US from intervening with the operation. Eisenhower specifically warned that the Americans, and the world, "would be outraged" unless all peaceful routes had been exhausted, and even then "the eventual price might become far too heavy".[137][138] London hoped that Nasser's engagement with communist states would persuade the Americans to accept British and French actions if they were presented as a fait accompli. This proved to be a critical miscalculation.

Franco-British-Israeli war plan

Objectives

Britain was anxious lest it lose efficient access to the remains of its empire. Both Britain and France were eager that the canal should remain open as an important conduit of oil.

Both the French and the British felt that Nasser should be removed from power. The French "held the Egyptian president responsible for assisting the anti-colonial rebellion in Algeria".[139] France was nervous about the growing influence that Nasser exerted on its North African colonies and protectorates.

Israel wanted to reopen the Straits of Tiran leading to the Gulf of Aqaba to Israeli shipping, and saw the opportunity to strengthen its southern border and to weaken what it saw as a dangerous and hostile state. This was particularly felt in the form of attacks injuring approximately 1,300 civilians emanating from the Egyptian-held Gaza Strip.[140]

The Israelis were also deeply troubled by Egypt's procurement of large amounts of Soviet weaponry that included 530 armoured vehicles, of which 230 were tanks; 500 guns; 150 MiG-15 jet fighters; 50 Ilyushin Il-28 bombers; submarines and other naval craft. The influx of this advanced weaponry altered an already shaky balance of power.[141] Israel was alarmed by the Czech arms deal, and believed it had only a narrow window of opportunity to hit Egypt's army.[142] Additionally, Israel believed Egypt had formed a secret alliance with Jordan and Syria.[143]

British planning

In July 1956, Eden ordered his Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Field Marshal Gerald Templer, to begin planning for an invasion of Egypt.[144] Eden's plan called for the Cyprus-based 16th Independent Parachute Brigade Group to seize the canal zone.[145] The Prime Minister's plan was rejected by Templer and the other service chiefs, who argued that the neglect of parachute training in the 16th Independent Parachute Brigade rendered his plan for an airborne assault unsuitable.[144] Instead, they suggested the sea-power based Contingency Plan, which called for the Royal Marines to take Port Said, which would then be used as a base for three British divisions to overrun the canal zone.[144]

In early August, the Contingency Plan was modified by including a strategic bombing campaign that was intended to destroy Egypt's economy, and thereby hopefully bring about Nasser's overthrow.[144] In addition, a role was allocated to the 16th Independent Parachute Brigade, which would lead the assault on Port Said in conjunction with the Royal Marine landing.[146] The commanders of the Allied Task Force led by General Stockwell rejected the Contingency Plan, which Stockwell argued failed to destroy the Egyptian Armed Forces.[146]

Franco-Israeli planning

In July 1956, IDF chief of staff General Moshe Dayan advised Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion that Israel should attack Egypt at the first chance, but Ben Gurion stated he preferred to attack Egypt with the aid of France.[147] On 7 August 1956 the French Defense Minister Maurice Bourgès-Maunoury asked Ben Gurion if Israel would attack Egypt together with France, to which he received a positive reply.[148] On 1 September 1956 the French government formally asked that France and Israel begin joint planning for a war against Egypt.[149] By 6 September 1956, Dayan's chief of operations General Meir Amit, was meeting with Admiral Pierre Barjot to discuss joint Franco-Israeli operations.[149] On 25 September 1956 Peres reported to Ben Gurion that France wanted Israel as an ally against Egypt, and that the only problem was Britain, which was opposed to Israel taking action against Nasser.[150] In late September 1956, the French Premier Guy Mollet had embarked upon a dual policy of attacking Egypt with Britain, and if the British backed out (as Mollet believed that they might), with Israel.[151] On 30 September 1956 secret Franco-Israeli talks on planning a war started in Paris, which were based on the assumption that Britain would not be involved.[152] The French very much wanted to use airfields in Cyprus to bomb Egypt, but being not certain about Britain's attitude, wanted to use Israeli airfields if the ones in Cyprus were not free.[153] Only on 5 October 1956 during a visit by General Maurice Challe to Britain where he met with Eden, were the British informed of the secret Franco-Israeli alliance.[154]

On 22 October 1956, during negotiations leading to the Protocol of Sèvres, David Ben-Gurion, Prime Minister of Israel, gave the most detailed explanation ever to foreign dignitaries, of Israel's overall strategy for the Middle East.[155][156][157] Shlaim called this Ben-Gurion's "grand design". His main objection to the "English plan" was that Israel would be branded as the aggressor while Britain and France would pose as peace-makers.

Instead he presented a comprehensive plan, which he himself called "fantastic", for the reorganization of the Middle East. Jordan, he observed, was not viable as an independent state and should therefore be divided. Iraq would get the East Bank in return for a promise to settle the Palestinian refugees there and to make peace with Israel while the West Bank would be attached to Israel as a semi-autonomous region. Lebanon suffered from having a large Muslim population which was concentrated in the south. The problem could be solved by Israel's expansion up to the Litani River, thereby helping to turn Lebanon into a more compact Christian state. ... Israel declares its intention to keep her forces for the purpose of permanent annexation of the entire area east of the El Arish-Abu Ageila, Nakhl-Sharm el-Sheikh, in order to maintain for the long term the freedom of navigation in the Straits of Eilat and in order to free herself from the scourge of the infiltrators and from the danger posed by the Egyptian army bases in Sinai. ... "I told him about the discovery of oil in southern and western Sinai, and that it would be good to tear this peninsula from Egypt because it did not belong to her, rather it was the English who stole it from the Turks when they believed that Egypt was in their pocket. I suggested laying down a pipeline from Sinai to Haifa to refine the oil."

Protocol of Sèvres

In October 1956, Eden, after two months of pressure, finally and reluctantly agreed to French requests to include Israel in Operation Revise.[145] The British alliances with the Hashemite kingdoms of Jordan and Iraq had made the British very reluctant to fight alongside Israel, lest the ensuing backlash in the Arab world threaten London's friends in Baghdad and Amman.[145] The coming of winter weather in November meant that Eden needed a pretext to begin Revise as soon as possible, which meant that Israel had to be included.[145] This was especially the case as many Conservative backbenchers had expected Eden to launch operations against Egypt in the summer, and were disappointed when Eden had instead chosen talks. By the fall of 1956, many Tory backbenchers were starting to grow restive about the government's seeming inability to start military action, and if Eden had continued to put off military action for the winter of 1956–57, it is possible that his government might not have survived.[145]

Three months after Egypt's nationalisation of the Suez Canal company, a secret meeting took place at Sèvres, outside Paris. Britain and France enlisted Israeli support for an alliance against Egypt. The parties agreed that Israel would invade the Sinai. Britain and France would then intervene, purportedly to separate the warring Israeli and Egyptian forces, instructing both to withdraw to a distance of 16 kilometres from either side of the canal.[158]

The British and French would then argue that Egypt's control of such an important route was too tenuous, and that it needed to be placed under Anglo-French management. David Ben-Gurion did not trust the British in view of their treaty with Jordan and he was not initially in favour of the plan, since it would make Israel alone look like the aggressor; however he soon agreed to it since such a good opportunity to strike back at Egypt might never again present itself.[158]

Under the Protocol of Sèvres, the following was agreed to:

- 29 October: Israel to invade the Sinai.

- 30 October: Anglo-French ultimatum to demand both sides withdraw from the canal zone.

- 31 October: Britain and France begin Revise.

Anglo-French Operation Musketeer

Stockwell offered up Operation Musketeer, which was to begin with a two-day air campaign that would see the British gain air superiority.[146] In place of Port Said, Musketeer called for the capture of Alexandria.[146] Once that city had been taken in assault from the sea, British armoured divisions would engage in a decisive battle of annihilation somewhere south of Alexandria and north of Cairo.[146]

Musketeer would require thousands of troops, leading the British to seek out France as an ally.[146] To destroy the 300,000-strong Egyptian Army in his planned battle of annihilation, Stockwell estimated that he needed 80,000 troops, while at most the British Army could spare was 50,000 troops; the French could supply the necessary 30,000 troops to make up the shortfall.[146]

On 11 August 1956, General Charles Keightley was appointed commander of Musketeer with the French Admiral Barjot as his deputy commander.[146] The appointment of Stockwell as the Allied Task Force commander charged with leading the assault on Egypt caused considerable disappointment with the other officers of the Task Force.[159] One French officer recalled that Stockwell was

Extremely excitable, gesticulating, keeping no part of him still, his hands, his feet, and even his head and shoulders perpetually on the go, he starts off by sweeping objects off the table with a swish of his swagger cane or in his room by using it to make golf-strokes with the flower vases and ash-trays. Those are the good moments. You will see him pass in an instant from the most cheerfully expressed optimism to a dejection that amounts to nervous depression. He is a cyclothymic. By turns courteous and brutal, refined and coarse, headstrong in some circumstances, hesitant and indecisive in others, he disconcerts by his unpredictable responses and the contradictions of which he is made up. One only of his qualities remains constant: his courage under fire.[159]

By contrast, the majority of the officers of the Task Force, both French and British, admired André Beaufre as an elegant yet tough general with a sharp analytical mind who always kept his cool.[159] Most of the officers of the Anglo-French Task Force expressed regret that it was Beaufre who was Stockwell's deputy rather the other way around.[159] A major problem both politically and militarily with the planning for Musketeer was the one-week interval between sending troops to the eastern Mediterranean and the beginning of the invasion.[160] Additionally, the coming of winter weather to the Mediterranean in late November would render the invasion impossible, which thus meant the invasion had to begin before then.[160] An additional problem was Eden, who constantly interfered with the planning and was so obsessed with secrecy that he refused to tell Keightley what his political objectives were in attacking Egypt: namely, whether he wanted to retake the Suez Canal or topple Nasser, or both.[161] Eden's refusal to explain to Keightley just what exactly he was hoping to accomplish by attacking Egypt exasperated Keightley to no end, and greatly complicated the planning process.[161]

In late August 1956, the French Admiral Pierre Barjot suggested that Port Said once again be made the main target, which lessened the number of troops needed and thus reduced the interval between sending forces to the eastern Mediterranean and the invasion.[162] Beaufre was strongly opposed to the change, warning that Barjot's modification of merely capturing the canal zone made for an ambiguous goal, and that the lack of a clear goal was dangerous.[162]

In early September, Keightley embraced Barjot's idea of seizing Port Said, and presented Revise.[162]

Britain's First Sea Lord, Admiral Louis Mountbatten strongly advised his old friend Prime Minister Anthony Eden against the Conservative plans to seize the Suez canal. He argued that such a move would destabilize the Middle East, undermine the authority of the United Nations, divide the Commonwealth and diminish Britain's global standing. His advice was not taken; he tried to resign but the political leadership of the Royal Navy would not let him. Instead he worked hard to prepare the Royal Navy for war with characteristic professionalism and thoroughness.[163][164]

Anglo-French Operation Revise

Operation Revise called for the following:

- Phase I: Anglo-French air forces to gain air supremacy over Egypt's skies.[162]

- Phase II: Anglo-French air forces were to launch a 10-day "aero-psychological" campaign that would destroy the Egyptian economy.[162]

- Phase III: Air- and sea-borne landings to capture the canal zone.[162]

On 8 September 1956 Revise was approved by the British and French cabinets.[162]

Both Stockwell and Beaufre were opposed to Revise as an open-ended plan with no clear goal beyond seizing the canal zone, but was embraced by Eden and Mollet as offering greater political flexibility and the prospect of lesser Egyptian civilian casualties.[162]

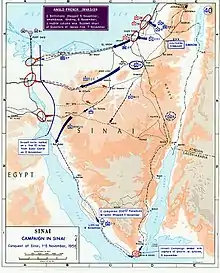

Israeli Operation Kadesh

At the same time, Israel had been working on Operation Kadesh for the invasion of the Sinai.[145] Dayan's plan put an emphasis on air power combined with mobile battles of encirclement.[145] Kadesh called for the Israeli Air Force to win air superiority, which was to be followed up with "one continuous battle" in the Sinai.[145] Israeli forces would in a series of swift operations encircle and then take the main Egyptian strong points in the Sinai.[145]

Reflecting this emphasis on encirclement was the "outside-in" approach of Kadesh, which called for Israeli paratroopers to seize distant points first, with those closer to Israel to be seized later.[145] Thus, the 202nd Paratroop Brigade commanded by Colonel Ariel Sharon was to land in the far-western part of the Sinai to take the Mitla Pass, and thereby cut off the Egyptian forces in the eastern Sinai from their supply lines.[145]

American intelligence

The American Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) was taking high-altitude photos of the allied activities, and more details came from human sources in London, Paris, and Tel Aviv. CIA chief Allen Dulles said that "intelligence was well alerted as to what Israel and then Britain and France were likely to do ... In fact, United States intelligence had kept the government informed".[165]

Forces

Britain

British troops were well-trained, experienced, and had good morale, but suffered from the economic and technological limitations imposed by post-war austerity.[166] The 16th Independent Parachute Brigade Group, which was intended to be the main British strike force against Egypt, was heavily involved in the Cyprus Emergency, which led to a neglect of paratroop training in favour of counter-insurgency operations.[166] The Royal Navy could project formidable power through the guns of its warships and aircraft flown from its carriers, but lacked amphibious capability.[167]

The Royal Navy had just undergone a major and innovative carrier modernisation program. The Royal Air Force (RAF) had just introduced two long-range bombers, the Vickers Valiant and the English Electric Canberra, but owing to their recent entry into service the RAF had not yet established proper bombing techniques for these aircraft.[167] Despite this, General Sir Charles Keightley, the commander of the invasion force, believed that air power alone was sufficient to defeat Egypt.[167] By contrast, General Hugh Stockwell, the Task Force's ground commander, believed that methodical and systematic armoured operations centred on the Centurion battle tank would be the key to victory.[168]

France

French troops were experienced and well-trained but suffered from cutbacks imposed by post-war politics of economic austerity.[169] In 1956, the French Armed Forces was heavily involved in the Algerian war, which made operations against Egypt a major distraction.[169] French paratroopers of the elite Regiment de Parachutistes Coloniaux (RPC) were extremely experienced, battle-hardened, and very tough soldiers, who had greatly distinguished themselves in the fighting in Indochina and in Algeria.[169] The men of the RPC followed a "shoot first, ask questions later" policy towards civilians, first adopted in Vietnam, which was to lead to the killing of a number of Egyptian civilians.[169] The rest of the French troops were described by the American military historian Derek Varble as "competent, but not outstanding".[169]

The main French (and Israeli) tank, the AMX-13, was designed for mobile, flanking operations, which led to a tank that was lightly armoured but agile.[169] General André Beaufre, who served as Stockwell's subordinate, favoured a swift campaign of movement in which the main objective was to encircle the enemy.[169] Throughout the operation, Beaufre proved himself to be more aggressive than his British counterparts, always urging that some bold step be taken at once.[169] The French Navy had a powerful carrier force which was excellent for projecting power inland, but, like its British counterpart, suffered from a lack of landing craft.[169]

Israel

American military historian Derek Varble called the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) the "best" military force in the Middle East while at the same time suffering from "deficiencies" such as "immature doctrine, faulty logistics, and technical inadequacies".[170] The IDF's Chief of Staff, Major General Moshe Dayan, encouraged aggression, initiative, and ingenuity among the Israeli officer corps while ignoring logistics and armoured operations.[170] Dayan, a firm infantry man, preferred that arm of the service at the expense of armour, which Dayan saw as clumsy, pricey, and suffering from frequent breakdowns.[170]

At the same time, the IDF had a rather disorganised logistics arm, which was put under severe strain when the IDF invaded the Sinai.[170] Most of the IDF weapons in 1956 came from France.[170] The main IDF tank was the AMX-13 and the main aircraft were the Dassault Mystère IVA and the Ouragan.[171] Superior pilot training was to give the Israeli Air Force an unbeatable edge over their Egyptian opponents.[170] The Israeli Navy consisted of two destroyers, seven frigates, eight minesweepers, several landing craft, and fourteen torpedo boats.

Egypt

In the Egyptian Armed Forces, politics rather than military competence was the main criterion for promotion.[172] The Egyptian commander, Field Marshal Abdel Hakim Amer, was a purely political appointee who owed his position to his close friendship with Nasser. A heavy drinker, he would prove himself grossly incompetent as a general during the Crisis.[172] In 1956, the Egyptian military was well equipped with weapons from the Soviet Union such as T-34 and IS-3 tanks, MiG-15 fighters, Ilyushin Il-28 bombers, SU-100 self-propelled guns and assault rifles.[172]

Rigid lines between officers and men in the Egyptian Army led to a mutual "mistrust and contempt" between officers and the men who served under them.[173] Egyptian troops were excellent in defensive operations, but had little capacity for offensive operations, owing to the lack of "rapport and effective small-unit leadership".[173]

Invasion

The Israeli operation Kadesh in Sinai

Operation Kadesh received its name from ancient Kadesh, located in the northern Sinai and mentioned several times in the Hebrew Pentateuch. Israeli military planning for this operation in the Sinai hinged on four main military objectives; Sharm el-Sheikh, Arish, Abu Uwayulah (Abu Ageila), and the Gaza Strip. The Egyptian blockade of the Tiran Straits was based at Sharm el-Sheikh and, by capturing the town, Israel would have access to the Red Sea for the first time since 1953, which would allow it to restore the trade benefits of secure passage to the Indian Ocean.

The Gaza Strip was chosen as another military objective because Israel wished to remove the training grounds for Fedayeen groups, and because Israel recognised that Egypt could use the territory as a staging ground for attacks against the advancing Israeli troops. Israel advocated rapid advances, for which a potential Egyptian flanking attack would present even more of a risk. Arish and Abu Uwayulah were important hubs for soldiers, equipment, and centres of command and control of the Egyptian Army in the Sinai.[174]

Capturing them would deal a deathblow to the Egyptian's strategic operation in the entire Peninsula. The capture of these four objectives were hoped to be the means by which the entire Egyptian Army would rout and fall back into Egypt proper, which British and French forces would then be able to push up against an Israeli advance, and crush in a decisive encounter. On 24 October, Dayan ordered a partial mobilisation.[174] When this led to a state of confusion, Dayan ordered full mobilisation, and chose to take the risk that he might alert the Egyptians.[174] As part of an effort to maintain surprise, Dayan ordered Israeli troops that were to go to the Sinai to be ostentatiously concentrated near the border with Jordan first, which was intended to fool the Egyptians into thinking that it was Jordan that the main Israeli blow was to fall on.[174]

On 28 October, Operation Tarnegol was effected, during which an Israeli Gloster Meteor NF.13 intercepted and destroyed an Egyptian Ilyushin Il-14 carrying Egyptian officers en route from Syria to Egypt, killing 16 Egyptian officers and journalists and two crewmen. The Ilyushin was believed to be carrying Field Marshal Abdel Hakim Amer and the Egyptian General Staff; however this was not the case.