Tamils

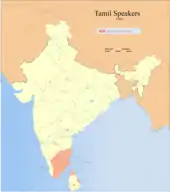

The Tamil people, also known as Tamilar (Tamil: தமிழர், romanized: Tamiḻar, pronounced [t̪amiɻaɾ] in the singular or தமிழர்கள், Tamiḻarkaḷ, [t̪amiɻaɾɣaɭ] in the plural), or simply Tamils (/ˈtæmɪls/), are a Dravidian ethno-linguistic group who trace their ancestry mainly to India’s southern state of Tamil Nadu, union territory of Puducherry and to Sri Lanka. Tamils constitute 5.9% of the population in India (concentrated mainly in Tamil Nadu and Puducherry), 15% in Sri Lanka (excluding Sri Lankan Moors),[note 3] 7% in Malaysia, 6% in Mauritius,[12] and 5% in Singapore.

தமிழர் | |

|---|---|

Tamil bride and groom performing the ritual of metti anidal | |

| Total population | |

| c. 76 million[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 69,026,881 (2011)[2] | |

| 3,135,770 (2012)[3] | |

| 1,800,000[1] | |

| 238,699+[4] | |

| 237,890 (2021)[5][note 1] | |

| 192,665+ (2015)[6][7][note 2] | |

| Other | See Tamil diaspora |

| Languages | |

| Tamil | |

| Religion | |

| Majority: Minority: | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| |

| Part of a series on |

| Tamils |

|---|

|

|

|

From the 4th century BCE,[13] urbanisation and mercantile activity along the western and eastern coasts of what is today Kerala and Tamil Nadu led to the development of four large Tamil empires, the Cheras, Cholas, Pandyas, and Pallavas and a number of smaller states, all of whom were warring amongst themselves for dominance. The Jaffna Kingdom, inhabited by Sri Lankan Tamils, was once one of the strongest kingdoms of Sri Lanka and controlled much of the north of the island.

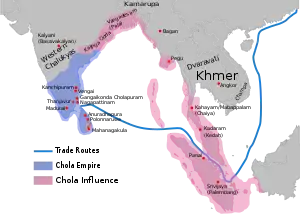

Tamils were noted for their influence on regional trade throughout the Indian Ocean. Artefacts marking the presence of Roman traders demonstrate that direct trade was active between Ancient Rome and Southern India, and the Pandyas were recorded as having sent at least two embassies directly to the Roman Emperor Augustus in Rome. The Pandyas and Cholas were historically active in Sri Lanka. The Chola dynasty successfully invaded several areas in southeast Asia, including the powerful Srivijaya and the city-state of Kedah.[14] Medieval Tamil guilds and trading organizations like the Ayyavole and Manigramam played an important role in Southeast Asian trading networks.[15] Pallava traders and religious leaders travelled to Southeast Asia and played an important role in the cultural Indianisation of the region. Scripts brought by Tamil traders to Southeast Asia, like the Grantha and Pallava scripts, induced the development of many Southeast Asian scripts such as Khmer, Javanese, Kawi, Baybayin, and Thai.

The Tamil language is one of the world's longest-surviving classical languages,[16][17] with a history dating back to 300 BCE. Tamil literature is dominated by poetry, especially Sangam literature, which is composed of poems composed between 300 BCE and 300 CE. The most important Tamil author was the poet and philosopher Thiruvalluvar, who wrote the Tirukkuṛaḷ, a group of treatises on ethics, politics, love and morality widely considered the greatest work of Tamil literature.[18] Tamil visual art is dominated by stylized Temple architecture in major centres and the productions of images of deities in stone and bronze. Chola bronzes, especially the Nataraja sculptures of the Chola period, have become notable symbols of Hinduism. A major part of Tamil performing arts is its classical form of dance, the Bharatanatyam, whereas the popular forms are known as Koothu. Classical Tamil music is dominated by the Carnatic genre, while gaana and dappan koothu are also popular genres. Tamil is an official language in Sri Lanka and Singapore. In 2004, Tamil was the first of six to be designated as a classical language of India.[19]

Although most Tamil people are Hindus, many follow a particular way of religious practice that is considered to be the Ancient Tamil religion, venerating a plethora of village deities and Ancient Tamil Gods.[20][21] A smaller number are Christians and Muslims, and a small Jain community survives from the classical period as well. Tamil cuisine is informed by varied vegetarian and non-vegetarian items, usually spiced with locally available spices. The music, the temple architecture, and the stylized sculptures favoured by the Tamil people as in their ancient nation are still being learnt and practised. English historian and broadcaster Michael Wood called the Tamils the last surviving classical civilization on Earth, because the Tamils have preserved substantial elements of their past regarding belief, culture, music, and literature despite the influence of globalization.[22]

Etymology

It is unknown whether the term Tamiḻar and its equivalents in Prakrit such as Damela, Dameda, Dhamila, and Damila was a self designation or a term denoted by outsiders. Epigraphic evidence of an ethnicity termed as such is found in ancient Sri Lanka, where a number of inscriptions have come to light dating from the 2nd century BCE mentioning Damela or Dameda persons. The well-known Hathigumpha inscription of the Kalinga ruler Kharavela refers to a T(ra)mira samghata (Confederacy of Tamil rulers) dated to 150 BCE. It also mentions that the league of Tamil kingdoms had been in existence 113 years before then. In Amaravati (located in present-day Andhra Pradesh) there is an inscription referring to a Dhamila-vaniya (Tamil trader) datable to the 3rd century CE.[23]

In the Buddhist Jataka story known as Akiti Jataka there is a mention of a Damila-rattha (Tamil dynasty). There were trade relationship between the Roman Empire and Pandyan Empire. As recorded by the Hellenistic Greek historian and geographer Strabo, the Roman Emperor Augustus of Rome received at Antioch an ambassador from a king called Pandyan of Dramira. Hence, it is clear that by at least 300 BCE, the ethnic identity of Tamils was formed as a distinct group.[23] Tamiḻar is etymologically related to Tamil, the language spoken by Tamil people. Southworth suggests that the name comes from tam-miz > tam-iz - "self-speak", or "our own speech".[24] Zvelebil suggests an etymology of tam-iz, with tam meaning "self" or "one's self", and "-iz" having the connotation of "unfolding sound". Alternatively, he suggests a derivation of tamiz < tam-iz < *tav-iz < *tak-iz, meaning in origin "the proper process (of speaking)".[25]

History

Pre-historic period

Possible evidence indicating the earliest presence of Tamil people in modern-day Tamil Nadu are the megalithic urn burials, dating from around 1500 BCE and onwards, which have been discovered at various locations in Tamil Nadu, notably in Adichanallur in Thoothukudi District[26][27] which conform to the descriptions of funerals in classical Tamil literature.[28]

Various legends became prevalent after the 10th century CE regarding the antiquity of the Tamil people. According to Iraiyanar Agapporul, a 10th/11th century annotation on the Sangam literature, the Tamil country extended southwards beyond the natural boundaries of the Indian peninsula comprising 49 ancient nadus (divisions). The land was supposed to have been destroyed by a deluge. The Sangam legends also alluded to the antiquity of the Tamil people by claiming tens of thousands of years of continuous literary activity during three Sangams.[29]

Classical period

Ancient Tamils had three monarchical states, headed by kings called "Vendhar" and several tribal chieftainships, headed by the chiefs called by the general denomination "Vel" or "Velir".[30] Still lower at the local level there were clan chiefs called "kizhar" or "mannar".[31] The Tamil kings and chiefs were always in conflict with each other, mostly over territorial hegemony and property. The royal courts were mostly places of social gathering rather than places of dispensation of authority; they were centres for distribution of resources. Ancient Tamil Sangam literature and grammatical works, Tolkappiyam; the ten anthologies, Pattuppāṭṭu; and the eight anthologies, Eṭṭuttokai also shed light on ancient Tamil people.[32] The kings and chieftains were patrons of the arts, and a significant volume of literature exists from this period. The literature shows that many of the cultural practices that are considered peculiarly Tamil date back to the classical period.[33]

Agriculture was important during this period, and there is evidence that networks of irrigation channels were built as early as the 3rd century BCE.[34] Internal and external trade flourished, and evidence of significant contact with Ancient Rome exists. Large quantities of Roman coins and signs of the presence of Roman traders have been discovered at Karur and Arikamedu.[35] There is evidence that at least two embassies were sent to the Roman Emperor Augustus by Pandya kings.[36] Potsherds with Tamil writing have also been found in excavations on the Red Sea, suggesting the presence of Tamil merchants there.[37] An anonymous 1st century traveller's account written in Greek, Periplus Maris Erytraei, describes the ports of the Pandya and Chera kingdoms in Damirica and their commercial activity in great detail. Periplus also indicates that the chief exports of the ancient Tamils were pepper, malabathrum, pearls, ivory, silk, spikenard, diamonds, sapphires, and tortoiseshell.[38]

The classical period ended around the 4th century CE with invasions by the Kalabhra, referred to as the kalappirar in Tamil literature and inscriptions.[39][40] These invaders are described as 'evil kings' and 'barbarians' coming from lands to the north of the Tamil country, but modern historians think they could have been hill tribes who lived north of Tamil country.[41] This period, commonly referred to as the Dark Age of the Tamil country, ended with the rise of the Pallava dynasty.[42][43]

Megalithic sarcophagus burial from Tamil Nadu

Megalithic sarcophagus burial from Tamil Nadu.jpg.webp) Virampatnam jewelry from funerary burial, 2nd century BCE, Tamil Nadu

Virampatnam jewelry from funerary burial, 2nd century BCE, Tamil Nadu Souttoukeny jewelry, 2nd century BCE, Tamil Nadu

Souttoukeny jewelry, 2nd century BCE, Tamil Nadu Map of ancient oceanic trade, and ports of Tamilakam

Map of ancient oceanic trade, and ports of Tamilakam Tamiḻakam during Sangam Period

Tamiḻakam during Sangam Period

Economy, trade and maritime

The Tamil country is strategically located in the Indian Ocean and had access to a sea trade route.

Imperial and post-imperial periods

The names of the three dynasties, Cholas, Pandyas, and Cheras, are mentioned in Tamil Sangam literature and grammatical works like Tolkappiyar refers to them as the "Three Glorified by Heaven", (Tamil: வாண்புகழ் மூவர், Vāṉpukaḻ Mūvar).[44] Later, they are mentioned in the Mauryan Empire's Pillars of Ashoka (inscribed 273–232 BCE) inscriptions, among the kingdoms, which though not subject to Ashoka, were on friendly and allied terms with him.[45] The king of Kalinga, Kharavela, who ruled around 150 BCE, is mentioned in the Hathigumpha inscription of the confederacy of the Tamil kingdoms that had existed for over 100 years.[46] The Cholas, Pandyas, Cheras, and Pallavas were followers of Hinduism, though for a short while some of them seem to have embraced Jainism and later converted to Hinduism.[42] After the fall of the Mauryan Empire, the Tamil kingdoms were allied with the Satavahana Dynasty.

These early kingdoms sponsored the growth of some of the oldest extant literature in Tamil. The classical Tamil literature, referred to as Sangam literature, is attributed to the period between 300 BCE and 300 CE.[47][29] The poems of Sangam literature, which deal with emotional and material topics, were categorised and collected into various anthologies during the medieval period. These Sangam poems paint the picture of a fertile land and of a people who were organised into various occupational groups. The governance of the land was through hereditary monarchies, although the sphere of the state's activities and the extent of the ruler's powers were limited through the adherence to the established order ("dharma"). Although the Pallava records can be traced from the 2nd century CE, they did not rise to prominence as an imperial dynasty until the 6th century. They transformed the institution of the kingship into an imperial one, and sought to bring vast amounts of territory under their direct rule. The Bhakti movement in Hinduism was founded at this time, and rose along with the growing influence of Jainism and Buddhism.[48] The Pallavas pioneered the building of large, ornate temples in stone which formed the basis of the Dravidian temple architecture. They came into conflict with the Kannada Chalukyas of Badami. During this period, the great Badami Chalukya King Pulakeshin II extended the Chalukya Empire up to the northern extents of the Pallava kingdom and defeated the Pallavas in several battles.[49] Pallava Narasimhavarman however reversed this victory in 642 by attacking and occupying Badami temporarily.[50] However a later Chalukya King Vikramaditya II took revenge by repeated invasions of the territory of Tondaimandalam and his subsequent victories over Pallava Nandivarman II and the annexation of Kanchipuram.[51] The Pallava dynasty was overthrown in the 9th century by the imperial Kannada Rashtrakutas who ruled from Gulbarga. Krishna III, the last great Rashtrakuta king, consolidated the empire so that it stretched from the Narmada River to the Kaveri River and included the northern Tamil country (Tondaimandalam) while levying tribute on the king of Ceylon.[52]

Under Rajaraja Chola and his son Rajendra Chola, the Cholas became dominant in the 10th century and established an empire covering most of South India and Sri Lanka. The empire had strong trading links with the Chinese Song Dynasty and southeast Asia.[53][54] The Cholas defeated the Eastern Chalukya and expanded their empire to the Ganges. They conquered the coastal areas around the Bay of Bengal and turned it into a Chola lake. Rajendra Chola improved his father's fleet and created the first notable marine of the Indian subcontinent. The Chola navy conquered the dominant Southeast Asian power, the Srivijaya Empire, and secured the sea trade route to China.[55] Cholas exacted tribute from Thailand and the Khmer Empire. The latter half of the 11th century saw the union of Chola and Vengi kingdoms under Kulottunga I.[56] The Chola emperor decisively repulsed an invasion by the Western Chalukya king Vikramaditya VI, who had tried to interfere in Chola politics by installing his puppet, and their defeat of him led to their annexation of Gangavadi and Konkan regions. Vikramaditya VI was confined to his own dominions north of the Tungabhadra.[57] The Chola empire remained formidable during the reign of Kulottunga and maintained its influence over the various kingdoms of Southeast Asia like the Sri Vijaya empire.[58][59] According to historian Nilakanta Sastri, Kulottunga avoided unnecessary wars and had a long and prosperous reign characterized by unparalleled success that laid the foundation for the well being of the empire for the next 150 years.[60]

The eventual decline of Chola power in South India began towards the end of Kulottunga III's reign. It was accentuated by the resurgence of Pandyas under Maravarman Sundara Pandya (1216-1238 CE)[55] The waning Chola fortunes resulted in a three-way fight for the Tamil regions between the Pandyas, the Hoysalas and the Kakatiyas. Even the Kadava chief, Kopperunjinga, rebelled against his Chola overlord, Rajaraja III, and asserted his independence. The Hoysalas played a divisive role in the politics of the Tamil country during this period. They thoroughly exploited the lack of unity among the Tamil kingdoms and alternately supported one Tamil kingdom against the other thereby preventing both the Cholas and Pandyas from rising to their full potential. During the period of Rajaraja III, the Hoysalas sided with the Cholas and defeated the Kadava chieftain Kopperunjinga and the Pandyas and established a presence in the Tamil country. Rajendra Chola III who succeeded Rajaraja III was a much better ruler who took bold steps to revive the Chola fortunes. He led successful expeditions to the north as attested by his epigraphs found as far as Cuddappah.[61] He also defeated two Pandya princes one of whom was Maravarman Sundara Pandya II and briefly made the Pandyas submit to the Chola overlordship. The Hoysalas, under Vira Someswara, were quick to intervene and this time they sided with the Pandyas and repulsed the Cholas in order to counter the latter's revival.[62]

Tamil history turned a new leaf with the advent of the warrior prince, Jatavarman Sundara Pandyan I. In the ensuing wars for supremacy, he emerged as the single most victorious ruler and the Pandya kingdom reached its zenith in the 13th century during his reign. Jatavarman Sundara Pandya first put an end to Hoysala interference by expelling them from the Kaveri delta and subsequently killed their king Vira Someswara in 1262 AD near Srirangam. He then defeated Kopperunjinga, the Kadava chieftain, and turned him into a vassal. The Pandya then turned his attention to the north and annexed Kanchi by killing the Telugu chief Vijaya Gandagopala. He then marched up to Nellore and celebrated his victories there by doing the virabisheka(anointment of heroes) after defeating the Kakatiya ruler, Ganapati. Meanwhile, his lieutenant Vira Pandya defeated the king of Lanka and obtained the submission of the island nation.[63] In the 14th century, the Pandyan empire was engulfed in a civil war and also had to face repeated invasions by the Delhi Sultanate. In 1335, Madurai, the Pandyan capital, was conquered by Jalaluddin Ahsan Khan and a short-lived Madurai Sultanate was established, but was captured in 1378 by the Vijayanagara Empire.

Throughout the 15th century, the Vijayanagara Empire was the dominant power of South India.In the early 16th century (about 1520 CE), Virasekhara Chola, king of Tanjore rose out of obscurity and plundered the dominions of the then Pandya prince in south. The Pandya who was under the protection of the Vijayanagara appealed to the emperor and the Raya accordingly directed his agent (Karyakartta) Nagama Nayaka who was stationed in the south to put down the Chola. Nagama Nayaka then defeated the Chola but to everyone's surprise the once loyal officer of Krishnadeva Raya defied the emperor for some reason and decided to keep Madurai for himself.[64] Krishnadeva Raya is then said to have dispatched Nagama's son, Viswanatha who defeated his father and restored Madurai to Vijayanagara.[65] The fate of Virasekhara Chola, the last of the line of Cholas is not known. It is speculated that he either fell in battle or was put to death along with his heirs during his encounter with Vijayanagara.[66] Later when the Vijayanagara empire crumbled and fell after the Battle of Talikota in 1565 CE, the Nayaks who had once been viceroys asserted their independence and ruled independently from Madurai and Thanjavur.[67]

The area west of the Western Ghats became increasingly politically distinct from the Eastern parts ruled by Chola and Pandya Dynasties[68] Kerala was until 9th century, culturally and linguistically part of Tamilakam, with the local Koduntamil evolving to Malayalam.[69] This socio-culturally transformation was altered through Sanskrit-speaking Indo-Aryan migration from Northern India in the 8th century.[70]

In Sri Lanka

| Part of a series on |

| Sri Lankan Tamils |

|---|

|

There is little scholarly consensus over the presence of Tamil people in Sri Lanka.[72] One theory is that cultural diffusion well before Sinhalese arrival in Sri Lanka led to Tamil replacing a previous language of an indigenous Mesolithic population that became the Sri Lankan Tamils.[73]

According to their tradition, Sri Lankan Tamils are lineal descendants of the aboriginal Naga and Yaksha people of Sri Lanka. The "Nakar" used the cobra totem known as "Nakam" in the Tamil language, which is still part of the Hindu Tamil tradition in Sri Lanka today as a subordinate deity.[74]

Pre-historic period

Settlements of people culturally similar to those of present-day Sri Lanka and Tamil Nadu in modern India were excavated at megalithic burial sites at Pomparippu on the west coast and in Kathiraveli on the east coast of the island, with villages established between the 5th century BCE and 2nd century CE.[75][76] Cultural similarities in burial practices in South India and Sri Lanka were dated by archeologists to the 10th century BCE. However, Indian history and archaeology have pushed the date back to the 15th century BCE, and in Sri Lanka, there is radiometric evidence from Anuradhapura that the non-Brahmi symbol-bearing black and red ware occurs at least around the 9th or 10th century BCE.[77]

Historic period

Early South Indian type black and red ware potsherds found in Sri Lanka, indicate that both region were bound by similar culture and identity.[78] The many Brahmic inscriptions found in Sri Lanka, with Tamil clan names such as Parumakal, Ay, Vel, Uti (Utiyan), Tissa (Ticaiyan), Cuda/Cula/Cola, Naka etc., point out to early close affinity between Sri Lanka and South India.[79] Potsherds with early Tamil writing from the 2nd century BCE have been found in excavations in north of the Sri Lanka in Poonagari, bearing several inscriptions including a clan name – vela, a name related to velir from ancient Tamil country.[80] Tamil Brahmi inscribed potsherds have also been excavated in the south of the island in Tissamaharama. There is epigraphic evidence of people identifying themselves as Damelas or Damedas (the Prakrit word for Tamil people) in Anuradhapura, the capital city of Rajarata, and other areas of Sri Lanka as early as the 2nd century BCE.[81] Historical records establish that Tamil kingdoms in modern India were closely involved in the island's affairs from about the 2nd century BCE.[82][83] In Mahavamsa, a historical poem, ethnic Tamil adventurers such as Elara invaded the island around 145 BCE.[84] Tamil soldiers from what is now South India were brought to Anuradhapura between the 7th and 11th centuries CE in such large numbers that local chiefs and kings trying to establish legitimacy came to rely on them.[85] By the 8th century CE there were Tamil villages collectively known as Demel-kaballa (Tamil allotment), Demelat-valademin (Tamil villages), and Demel-gam-bim (Tamil villages and lands).[86]

Medieval period

In the 9th and 10th centuries CE, Pandya and Chola incursions into Sri Lanka culminated in the Chola annexation of the island, which lasted until the latter half of the 11th century CE, after which Chola influence declined in Sri Lanka.[85][87] The Chola decline in Sri Lanka was followed by the restoration of the Polonnaruwa monarchy in the late 11th century CE.[88] In 1215, following Pandya invasions, the Tamil-dominant Aryacakaravarthi dynasty established the Jaffna Kingdom[89] on the Jaffna peninsula and in parts of northern Sri Lanka. The Aryacakaravarthi expansion into the south was halted by Akalesvara Alagakkonara, the descendant of a powerful feudal family from Kanchipuram that migrated to Sri Lanka around the 13th century and converted to Buddhism.[90] Akalesvara was the chief minister of the Sinhalese king Parakramabahu V (1344–59 CE) and soon became the real power behind the throne. Vira Alakeshwara, a descendant of Alagakkonara, later became king of the Sinhalese,[91] but the Ming admiral Zheng He overthrew him in 1409 and took him as a captive to China, after which his family declined in influence. The Aryachakaravarthi dynasty continued to rule over large parts of northeast Sri Lanka until the Portuguese conquest of the Jaffna Kingdom in 1619. The coastal areas of the island were taken over by the Dutch and then became part of the British Empire in 1796. The English sailor Robert Knox described walking into the island's Tamil country in the publication An Historical Relation of the Island Ceylon, annotating some kingdoms within it on a map in 1681.[92] Upon the arrival of European powers from the 17th century, the Tamils' separate nation was described in their areas of habitation in the northeast of the island.[93]

The caste structure of the majority Sinhalese has also accommodated Hindu immigrants from South India since the 13th century CE. This led to the emergence of three new Sinhalese caste groups: The "Radala" the Salagama, the Durava and the Karava.[94][95][96] The Hindu migration and assimilation continued until the 18th century.[94]

Modern period

British colonists consolidated the Tamil territory in southern India into the Madras Presidency, which was integrated into British India. Similarly, the Tamil speaking parts of Sri Lanka joined with the other regions of the island in 1802 to form the Ceylon colony. Ceylon remained in political union with India until India's independence in 1947; it gained independence the following year, as Sri Lanka, with both Sinhalese and Tamil populations.

The post-independence period and the Civil War

Tamil Eelam is a proposed independent state that Sri Lankan Tamils and the Sri Lankan Tamil diaspora aspire to establish in the north and east of Sri Lanka.[97][98] Irrespective of the ethnic differences, the British imposed a unitary state structure in British Ceylon for better administration.[99] During the British colonial rule, many Tamils held higher positions than the Sinhalese in the government, because they were favoured by the British for their qualification in English education. In the Sri Lankan highlands the lands of the Sinhalese were seized by the British and Indian Tamils were settled there as plantation workers.[100] After the British colonial rule in Sri Lanka ended, ethnic tension between the Sinhalese and the Sri Lankan Tamils rose. The Sinhalese, constituting a majority of the country, resented the minority Tamils having huge power in the island. In 1948 about 700,000 Indian Tamil tea plantation workers from Sri Lanka were made stateless and deported to India. In 1956 the Prime Minister of Sri Lanka passed the Sinhala Only Act, an act where Sinhala replaced English as the only official language of Sri Lanka. Due to this, many Tamils were forced to resign as civil servants/public servants because they were not fluent in Sinhala.[101] The Sri Lankan Tamils saw the act as linguistic, cultural and economic discrimination against them.

After anti-Tamil pogroms in 1956, 1958 and 1977 and a brutal crackdown against Tamils protesting against these acts, guerrilla groups like the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (Tamil Tigers) were established. They aimed to set up an independent Tamil state, Tamil Eelam, for majority-Tamil regions in Sri Lanka. The burning of Jaffna library in 1981 and Black July in 1983 finally led to over 25 years of war between the Sri Lankan army and the Tamil Tigers, in which both sides committed numerous atrocities. This Sri Lankan civil war led to death of over 100,000 people, according to the United Nations.[102] The Sri Lankan government and Tamil Tigers allegedly committed war crimes against the civilian Sri Lankan Tamil people during the final months of the Eelam War IV phase in 2009, when the leader of the Tigers, Prabhakaran, was killed.[103] The war led to the flight of over 800,000 Sri Lankan Tamil refugees, many going to the UK and India.

Geographic distribution

India

Most Tamils in India live in the state of Tamil Nadu. Tamils are the majority in the union territory of Puducherry, a former French colony. Puducherry is a subnational enclave situated within Tamil Nadu. Tamils account for at least one-sixth of the population in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

There are significant Tamil communities in other parts of India. Most of these have emerged fairly recently, dating to the colonial and post-colonial periods, but some date back to the medieval period. Significant populations reside in Karnataka (3 million), Maharashtra (0.4 million), Andhra Pradesh (1.2 million), Kerala (0.6 million), Gujarat (0.1 million) and the National Capital Region (0.1 million).[104]

Sri Lanka

There are two groups of Tamils in Sri Lanka: the Sri Lankan Tamils and the Indian Tamils. The Sri Lankan Tamils (or Ceylon Tamils) are descendants of the Tamils of the old Jaffna Kingdom and east coast chieftaincies called Vannimais. The Indian Tamils (or Hill Country Tamils) are descendants of bonded laborers who migrated from Tamil Nadu to Sri Lanka in the 19th century to work on tea plantations.[105] There also exists a significant Muslim population in Sri Lanka who are speakers of the Tamil language. Due to independent lineage, they are listed[9][11] as Moors by the Sri Lankan government.[106][107]

Most Sri Lankan Tamils live in the Northern and Eastern provinces and in the capital Colombo, whereas most Indian Tamils live in the central highlands.[107] Historically both groups have seen themselves as separate communities, although there has been a greater sense of unity since the 1980s.[108]

Under the terms of an agreement reached between the Sri Lankan and Indian governments in the 1960s, about 40 percent of the Indian Tamils were granted Sri Lankan citizenship, and many of the remainder were repatriated to India. By the 1990s, most Indian Tamils had received Sri Lankan citizenship.[109]

Tamil diaspora

Significant Tamil emigration began in the 18th century, when the British colonial government sent many middle-class and poor Tamils as indentured labourers to far-off parts of the Empire, especially Malaya, Burma, South Africa, Fiji, Mauritius, Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, Suriname, Jamaica, French Guiana, Guadeloupe, and Martinique. At about the same time, many Tamil businessmen also migrated to other parts of the British Empire, particularly to Burma and East Africa.[110]

Many Tamils still live in these countries, and the Tamil communities in Singapore, Reunion Island, Malaysia, Myanmar and South Africa have retained much of their original culture, tradition and language. Many Malaysian children attend Tamil schools, and a significant portion of Tamil children are brought up with Tamil as their first language. In Singapore, Mauritius and Reunion, Tamil students learn Tamil as their second language in school. In Singapore, to preserve the Tamil language, the government has made it an official language despite Tamils comprising only about 5% of the population, and has also introduced compulsory instruction of the language for Tamils. Other Tamil communities, such as those in South Africa, Fiji, Mauritius, Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, Suriname, Jamaica, French Guiana, Guadeloupe, Pakistan, Martinique, and the Caribbean no longer speak Tamil language as a first language, but still retain a strong Tamil identity, and are able to understand the language, while most elders speak it as a first language.[111] There is a very small Tamil community in Pakistan, notably settled since the partition in 1947.[112]

A large emigration also began in the 1980s, as Sri Lankan Tamils sought to escape the ethnic conflict there. These recent emigrants have most often moved to Australia, Europe, North America and southeast Asia.[113] Today, the largest concentration of Sri Lankan Tamils outside Sri Lanka can be found in Toronto.[114]

Culture

Language and literature

Tamils have strong attachment to the Tamil language, which is often venerated in literature as Tamil̲an̲n̲ai, "the Tamil mother".[115] It has historically been, and to large extent still is, central to the Tamil identity.[116] It is a Dravidian language, with little relation to the Indo-European languages of northern India. The language has been far less influenced by Sanskrit than the other Dravidian languages, and preserves many features of Proto-Dravidian, though modern-day spoken Tamil in Tamil Nadu freely uses loanwords from Sanskrit and English.[117] Tamil literature is of considerable antiquity, and underpins the decision to recognise Tamil as a classical language by the government of India. Classical Tamil literature, which ranges from lyric poetry to works on poetics and ethical philosophy, is remarkably different from contemporary and later literature in other Indian languages, and represents the oldest body of secular literature in South Asia.[118]

Religion

Tamil religion denotes the religious traditions and practices of Tamil-speaking people. The Tamils are native to modern state of India known as Tamil Nadu and the northern and eastern part of Sri Lanka. Tamils also live outside their native boundaries due to migration such as Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, South Africa, Australia, Great Britain, United States, Canada, Réunion, Myanmar, Mauritius and in countries in Europe. Many emigrant Tamils retain elements of a cultural, linguistic, and religious tradition that predates the Christian era.

Ancient Tamil grammatical works, Tolkappiyam; the ten anthologies, Pathupattu; and the eight anthologies, Ettuthogai shed light on early religion. Murugan was glorified as "the red god seated on the blue peacock, who is ever young and resplendent" as "the favored god of the Tamils." Sivan was also seen as the supreme God.[32] The Sangam landscape was classified into five categories, thinais, based on the mood, the season and the land. Tolkappiyam mentions that each of these thinai had an associated deity such as Seyyon in Kurinji-the hills, Thirumal in Mullai-the forests, Vendhan in Marutham-the plains, Kadalon in the Neithal-the coasts & the seas and Kottravai in Paalai- the deserts. Other gods mentioned were Mayyon and Vaali who are major deities in Hinduism today. Mercantile groups from Tamilakam and Kerala introduced Cholapauttam, a syncretic form of Buddhism and Shaivism in northern Sri Lanka and Southern India. This religion was transmitted through the Tamil language. The religion lost its importance in the 14th century when conditions changed for the benefit of Sinhala/Pali traditions.[119]

The cult of the mother goddess is treated as an indication of a society which venerated femininity. Amman, Mariamman, Durgai, Lakshmi, Saraswati, Kali and Saptakanniyar are venerated in all their forms.[120] The temples of the Sangam days, mainly of Madurai, seem to have had priestesses to the deity, who also appear predominantly as goddesses. In the Sangam literature, there is an elaborate description of the rites performed by the Kurava priestess in the shrine Palamutircholai.[121]

About 88%[122] of the population of Tamil Nadu were Hindus in 2001.

In Tamil Nadu, Christians and Muslims accounted for 6% and 5.8% respectively in 2001.[122] The majority of Muslims in Tamil Nadu speak Tamil,[123] with less than 15% of them reporting Urdu as their mother tongue.[124] Tamil Jains now number only a few thousand.[125] Atheist, rationalist, and humanist philosophies are also adhered by sizeable minorities.[126]

The most popular Tamil deity is Murugan; he is known as the patron god of the Tamils and is also called "Tamil Kadavul" (Tamil God).[127][128] In Tamil tradition, Murugan is the youngest and Pillaiyar the oldest son of Sivan and Parvati. The goddess Parvati is often depicted as a goddess with green skin complexion in Tamil Hindu tradition. The worship of Amman, also called Mariamman, thought to have been derived from an ancient mother goddess, is also very common.[129] Kannagi, the heroine of the Cilappatikaram, is worshipped as Pattini by many Tamils, particularly in Sri Lanka.[130] There are also many followers of Ayyavazhi in Tamil Nadu, mainly in the southern districts.[131] In addition, there are many temples and devotees of Thirumal, Sivan, Pillaiyar, and the other Hindu deities.

Muslims across Tamil Nadu follow Hanafi and Shafi'i schools while the Tamil Muslims in Sri Lanka follow the Shadhili school. While the Marakkayar, Labbai and Kayalar sects claim descent from the Arab world, the Rowther sects Claim descent from the Turkic world.[132]

Among the ancient Tamils the practice of erecting memorial stones (natukal) had appeared, and it continued for quite a long time after the Sangam age, down to about the 16th century.[133] It was customary for people who sought victory in war to worship these hero stones to bless them with victory.[134] They often carry inscriptions displaying a variety of adornments, including bas relief panels, friezes, and figures on carved stone.

The most important Tamil festivals are Pongal, a harvest festival that occurs in mid-January, and Varudapirappu, the Tamil New Year, which occurs on 14 April. Both are celebrated by almost all Tamils, regardless of religion. The Hindu festival Deepavali is celebrated with fanfare; other local Hindu festivals include Thaipusam, Panguni Uttiram, and Adiperukku. While Adiperukku is celebrated with more pomp in the Cauvery region than in others, the Ayyavazhi Festival, Ayya Vaikunda Avataram, is predominantly celebrated in the southern districts of Kanyakumari District, Tirunelveli, and Thoothukudi.

In rural Tamil Nadu, many local deities, called aiyyanars, are thought to be the spirits of local heroes who protect the village from harm.[135] Their worship often centres around natukal, stones erected in memory of heroes who died in battle. This form of worship is mentioned frequently in classical literature and appears to be the surviving remnants of an ancient Tamil tradition.[136] Munis are a group of guardian gods, who are worshiped by Tamils. The Saivist tradition of Hinduism is significantly represented amongst Tamils, more so among Sri Lankan Tamils, although most of the Saivist places of religious significance are in northern India. The Alvars and Nayanars, who were predominantly Tamils, played a key role in the renaissance of Bhakti tradition in India. In the 10th century, the philosopher Ramanuja propagated the theory of Visishtadvaitam.[137] Kambaramayanam is the Tamil version of the Hindu epic Ramayana, which was written by the Tamil poet Kambar during the 12th century. The Tamil version is smaller than the original Ramayana written by Valmiki. It is not a translation but tells the story in a different perspective.

Tamil Jains constituted around 0.13% of the population of Tamil Nadu in 2001.[122] Many of the classical Tamil literature works were written by Jains.[138] According to George L. Hart, the legend of the Tamil Sangams or literary assemblies was based on the Jain sangham at Madurai.[139]

Martial traditions

Various martial arts including Kuttu Varisai, Varma Kalai, Silambam, Adithada, and Malyutham are practised in Tamil Nadu.[140] The warm-up phase includes yoga, meditation and breathing exercises. Silambam originated in ancient Tamilakam and was patronized by the Pandyans, Cholas and Cheras, who ruled over this region. Silapathiharam, Tamil literature from the 2nd century CE, refers to the sale of Silamabam instructions, weapons and equipment to foreign traders.[141] Since the early Sangam age, there was a warlike culture in South India. War was regarded as an honorable sacrifice and fallen heroes and kings were worshiped in the form of a hero stone. Each warrior was trained in martial arts, horse riding and specialized in two of the weapons of that period: Vel (spear), Val (sword), and Vil (bow).[142] Heroic martyrdom was glorified in ancient Tamil literature. The Tamil kings and warriors followed an honour code similar to that of Japanese samurai and committed suicide to preserve honor. The forms of martial suicide were known as Avipalli, Thannai, Verttal, Marakkanchi, Vatakkiruttal and Punkilithu Mudiyum Maram. Avipalli was mentioned in all the works except Veera Soliyam. It was a self-sacrifice of a warrior to the goddess of war for the victory of his commander.[143] The Tamil rebels in Sri Lanka reflected some elements of Tamil martial traditions which included worship of fallen heroes (Maaveerar Naal) and practice of martial suicide. They carried a suicide pill around their neck to escape captivity and torture.[144]

Wootz steel originated in South India and Sri Lanka.[145][146] There are several ancient Tamil, Greek, Chinese and Roman literary references to high-carbon Indian steel since the time of Alexander's India campaign. The crucible steel production process started in the sixth century BCE at Kodumanal in Tamil Nadu, Golconda in Andhra Pradesh, in Karnataka and in Sri Lanka. It was exported globally, with the Tamils of the Chera Dynasty producing what was termed "the finest steel in the world", i.e. Seric Iron to the Romans, Egyptians, Chinese and Arabs by 500 BCE.[147][148][149] The steel was exported as cakes of steely iron that came to be known as "Wootz".[150]

The Tamilakam method was to heat black magnetite ore in the presence of carbon in a sealed clay crucible inside a charcoal furnace. An alternative was to smelt the ore first to give wrought iron, then heated and hammered to be rid of slag. The carbon source was bamboo and leaves from plants such as avārai.[150][151] The Chinese and locals in Sri Lanka adopted the production methods of creating Wootz steel from the Chera Tamils by the 5th century BCE.[152][153] In Sri Lanka, this early steel-making method employed a unique wind furnace, driven by the monsoon winds, capable of producing high-carbon steel. Production sites from antiquity have emerged, in places such as Anuradhapura, Tissamaharama and Samanalawewa, as well as imported artefacts of ancient iron and steel from Kodumanal. A 200 BCE Tamil trade guild in Tissamaharama, in the South East of Sri Lanka, brought with them some of the oldest iron and steel artefacts and production processes to the island from the classical period.[154][155][156] The Arabs introduced the South Indian/Sri Lankan wootz steel to Damascus, where an industry developed for making weapons of this steel. The 12th century Arab traveller Edrisi mentioned the "Hinduwani" or Indian steel as the best in the world.[145] Another sign of its reputation is seen in a Persian phrase – to give an "Indian answer", meaning "a cut with an Indian sword".[157] Wootz steel was widely exported and traded throughout ancient Europe and the Arab world, and became particularly famous in the Middle East.[157]

Traditional weapons

The Tamil martial arts also includes various types of weapons.

- Valari (Boomerang)

- Maduvu (deer horns)

- Surul vaal (curling blade)

- Vaal (sword) + Kedayam (shield)

- eetti or Vel (spear)

- Savuku (whip)

- Kattari (fist blade)

- Veecharuval (Billhook Machete)

- Silambam (long bamboo staff)

- Kuttu kattai (spiked knuckleduster)

- Katti (dagger/knife)

- Vil (bow) + Ambu (arrow)

- Tantayutam (mace)

- Soolam (trident)

Visual art and architecture

Most traditional art is religious in some form and usually centres on Hinduism, although the religious element is often only a means to represent universal—and, occasionally, humanist—themes.[158]

The most important form of Tamil painting is Tanjore painting, which originated in Thanjavur in the 9th century. The painting's base is made of cloth and coated with zinc oxide, over which the image is painted using dyes; it is then decorated with semi-precious stones, as well as silver or gold thread.[159] A style which is related in origin, but which exhibits significant differences in execution, is used for painting murals on temple walls; the most notable example are the murals on the Koodal Azhagar temple and Meenakshi temple of Madurai, and the Brihadeeswarar temple of Tanjore.[160]

Tamil sculpture ranges from elegant stone sculptures in temples, to bronze icons with exquisite details.[161] The medieval Chola bronzes are considered to be one of India's greatest contributions to world art.[162][163] Unlike most Western art, the material in Tamil sculpture does not influence the form taken by the sculpture; instead, the artist imposes his/her vision of the form on the material.[164] As a result, one often sees in stone sculptures flowing forms that are usually reserved for metal.[165]

Music

Ancient Tamil works, such as the Cilappatikaram, describe a system of music,[166] and a 7th-century Pallava inscription at Kudimiyamalai contains one of the earliest surviving examples of Indian music in notation.[167] Dance forms such as Bharatanatyam have recent origins but are based on older temple dance forms known as Catir Kacceri as practised by courtesans and a class of women known as Devadasis.[168]

Performing arts

.jpg.webp)

Notable Tamil dance styles are

- Bharatanatyam (Tamil classical dance)

- Karakattam (Tamil ancient folk dance)

- Koothu (A folk and street dance)

- Parai attam (A folk drums and dance)

- Kavadiattam (dedicated to the Tamil God Murugan)

- Kummiyattam (female folk dance)

- Bommalattam (Puppet dance)

- Puliyattam (Tiger dance)

- Mayilattam (Peacock dance)

- Paampu attam (Snake dance)

- Oyilattam (Dance of Grace)

- Poikkaal Kuthirai Aattam (False legged horses dance)

In its religious form, the karakattam dance is performed in front of an image of the goddess Mariamma.[169] The kuravanci is a type of dance-drama, performed by four to eight women. The drama is opened by a woman playing the part of a female soothsayer of the kurava tribe (people of hills and mountains), who tells the story of a lady pining for her lover. The therukoothu, literally meaning "street play", is a form of village theater or folk opera. It is traditionally performed in village squares, with no sets and very simple props.[170] The performances involve songs and dances, and the stories can be either religious or secular.[171] Tamil Nadu also has a well developed stage theatre tradition, which has been influenced by western theatre. A number of theatrical companies exist, with repertoires including absurdist, realist, and humorous plays.[172]

Film and theatre arts

Theatrical culture flourished among Tamils during the classical age. Tamil theatre has a long and varied history whose origins can be traced back almost two millennia to dance-theatre forms like Kotukotti and Pandarangam, which are mentioned in an ancient anthology of poems entitled the Kalingathu Parani.[173] The modern Tamil film industry originated during the 20th century, has its headquarters in Chennai and is known as Kollywood; it is the second largest film industry in India after Bollywood.[174] Films from Kollywood have been distributed to overseas theatres in Singapore, Sri Lanka, South Africa, Malaysia, Japan, Oceania, the Middle East, Western Europe, and North America.[175] Independent Tamil film production inspired by Kollywood originated outside India in Sri Lanka, Singapore, Canada, and western Europe. Several Tamil actresses such as Anushka Ranjan, Vyjayanthimala, Hema Malini, Rekha Ganesan, Sridevi, Meenakshi Sheshadri, Adah Sharma and Vidya Balan have acted in Bollywood and dominated the cinema over the years. Some Chief Ministers of Tamil Nadu, such as MG Ramachandran, Karunanidhi and Jayalalithaa, have had a background in the Tamil film industry.

Sports in Tamil Nadu

The people of Tamil Nadu play traditional sports and sports from other countries. Tamil Nadu has some notable players in each sport.

- Jallikattu: a bull-taming sport in Tamil Nadu that is over 2,000 years old and an integral part of Tamil culture. In ancient times, two bull-taming and bull-racing sports were pursued, called manjuvirattu and yeruthazhuval, with the aim of keeping people's temperament fit and ready for war at any time. Each has its own techniques and rules. Proficiency in these sports was one of the criteria for marrying girls of a warrior family. There were traditions where the winner would be chosen as bridegroom for their daughter or sister. On the other hand, the untamable bulls were held as a pride of the owner/village and used for breeding the cows. Unlike western bullfighting, bulls and warriors participated in the sport year after year. The sport, popular amongst warriors in the classical period,[176][177] survives in parts of Tamil Nadu, notably Alanganallur near Madurai, where it is held once a year around the time of the Pongal festival.

- Kabaddi: a traditional sport that originated in Tamil Nadu.[178]

- Mattu Vandy Elgai Panthayam (Reckla Race): bullock cart racing is mostly celebrated in southern Tamil Nadu.

- Silambam (Staff fencing): a martial art originated in the ancient Tamilakam. In 1978, the Tamil Nadu government and Tamil Nadu Olympic Federation recognised silambam as a traditional sport, but it was not recognised by the Sports Ministry of India and Indian Olympic Association.[179]

Tamil cuisine

Tamil cuisine includes vegetarian and non-vegetarian food. Some Tamils are vegetarian because of religious reasons.[180] Rice is mostly eaten with vegetarian and non-vegetarian curries. Traditionally, the Tamils sit on the ground and the food is served on a banana leaf. The traditional foods are eaten with the right hand. Dishes such as dosa, idli, and vadai are served with sambar, chutney or in Sri Lanka with coconut sambal. Rasam replaces soup in Tamil cuisine. The Tamil cuisine in Sri Lanka differs little from that of South India.[181] A famous Sri Lankan Tamil specialty is kottu roti, available in most Sri Lankan restaurants in the country and abroad.

See also

- List of languages by first written accounts

- Tamil population by cities

- Tamil population by nation

- Kumari Kandam

Notes

- Statistic includes all speakers of the Tamil language, as many multi-generation individuals do not speak the language as a mother tongue, but instead as a second or third language.

- Note: The Singapore Tamil population data excludes Tamils who were unable to speak and those in one-person households and households comprising only unrelated persons.

- Tamils in Sri Lanka are classified into three ethnicities by the Sri Lankan government, namely Sri Lankan Tamils, Indian Origin Tamils and Sri Lankan Moors who accounted for 11.2%, 4.1% and 9.3% respectively of the country's population in 2011.[8] Indian Origin Tamils were separately classified in the 1911 census onwards, while the Sri Lankan government lists a substantial Tamil-speaking Muslim population as a distinct ethnicity. However, much of the available genealogical evidence suggests that the Sri Lankan Moor community are of Tamil ethnicity, and that the majority of their ancestors were also Tamils who had lived in the country for generations, and had simply converted to Islam from other faiths.[9][10][11] It is also evidenced by the fact that Sri Lankan Moors were not a self-defined group of people and neither did the 'Moor' identity exist before the arrival of Portuguese colonists.

References

- Tamil at Ethnologue (19th ed., 2016)

- Statement 1 : Abstract of speakers' strength of languages and mother tongues – 2011, Censusindia.gov

- "Census of Population and Housing of Sri Lanka, 2012 – Table A3: Population by district, ethnic group and sex" (PDF). Department of Census and Statistics, Sri Lanka.

- ""Commuting Times, Median Rents and Language other than English Use"". Census.gov. 7 December 2017. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (17 August 2022). "Knowledge of languages by age and gender: Canada, provinces and territories, census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations with parts". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 12 October 2022.

- "Basic Demographic Characteristics: Table 6 Indian Resident Population by Age Group, Dialect Group and Sex". Census of Population 2010 Statistical Release 1: Demographic Characteristics, Education, Language and Religion. Department of Statistics, Singapore. Archived from the original on 8 September 2013.

- General Household Survey 2015 - Department of Statistics, Ministry of Trade & Industry, Republic of Singapore, Web.archive.org

- "A2: Population by ethnic group according to districts, 2012". Department of Census & Statistics, Sri Lanka.

- Mohan, Vasundhara (1987). Identity Crisis of Sri Lankan Muslims. Delhi: Mittal Publications. pp. 9–14, 27–30, 67–74, 113–18.

- "Ross Brann, "The Moors?"" (PDF). Drum.lib.umd.edu. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- "Analysis: Tamil-Muslim divide". BBC News World Edition. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Lal, Mohan, ed. (1992). Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature: Sasay to Zorgot. Sahitya Akademi. p. 4283.

- Nagapattinam to Suvarnadwipa: Reflections on the Chola Naval Expeditions to Southeast Asia by Hermann Kulke, K Kesavapany, Vijay Sakhuja p. 79

- The Emporium of the World: Maritime Quanzhou, 1000–1400 by Angela Schottenhammer p. 293

- Stein, B. (1977), "Circulation and the Historical Geography of Tamil Country", The Journal of Asian Studies, 37 (1): 7–26, doi:10.2307/2053325, JSTOR 2053325, S2CID 144599197

- Steever 1998, pp. 6–9

- Lal, Mohan, ed. (1992). Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature: Sasay to Zorgot. Sahitya Akademi. p. 4284.

- "Front Page : Tamil to be a classical language". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 18 September 2004. Archived from the original on 3 March 2018. Retrieved 1 August 2010.

- "Tamilar Madham - Contents Page". www.tamilvu.org. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- Cutler, Norman (1983). Clothey, Fred W.; Ramanujan, A. K.; Shulman, David Dean (eds.). "Tamil Religion: Melting Pot or Battleground?". History of Religions. 22 (4): 381–391. doi:10.1086/462931. ISSN 0018-2710. JSTOR 1062405. S2CID 162366616.

- Wood, Michael (2 August 2007). A South Indian Journey: The Smile of Murugan. Penguin UK. pp. x, xiii, xvi. ISBN 978-0-14-193527-0.

- Indrapala, K. (2007). The Evolution of an ethnic identity: The Tamils of Sri Lanka. Vijitha Yapa. pp. 155–56. ISBN 978-955-1266-72-1.

- Southworth, Franklin C. (1998), "On the Origin of the word tamiz", International Journal of Dravidial Linguistics, 27 (1): 129–32

- Zvelebil, Kamil V. (1992), Companion Studies to the history of Tamil literature, Leiden: E.J. Brill, pp. x–xvi

- John, Vino (27 January 2006), Reading the past in a more inclusive way: Interview with Dr. Sudharshan Seneviratne, Frontline, archived from the original on 2 February 2009, retrieved 9 July 2008,

But Indian/south Indian history/archaeology has pushed the date back to 1500 B.C., and in Sri Lanka, there are definitely good radiometric dates coming from Anuradhapura that the non-Brahmi symbol-bearing black and red ware occur at least around 900 B.C. or 1000 B.C.

- Comparative excavations carried out in Adichanallur in Thirunelveli district and in Northern India have provided evidence of a southward migration of the Megalithic culture – K.A.N. Sastri, A History of South India, pp. 4&>'67

- Codrington, K. De B. (October 1930), "Indian Cairn- and Urn-Burials", Man, 30 (30): 190–196, doi:10.2307/2790468, JSTOR 2790468,

It is necessary to draw attention to certain passages in early Tamil literature which throw a great deal of light upon this strange burial ceremonial ...

- Sastri, K. A. Nilakanta (1955). A History of South India. Oxford University Press. p. 105.

- Sastri, K. A. Nilakanta (1955). A History of South India. Oxford University Press. pp. 109–12.

- "Perspectives on Kerala History". P.J. Cherian (ed). Kerala Council for Historical Research. Archived from the original on 26 August 2006. Retrieved 15 November 2006.

There were three levels of redistribution corresponding to the three categories of chieftains, namely: the Ventar, Velir and Kilar in descending order. Ventar were the chieftains of the three major lineages, viz Cera, Cola and Pandya. Velir were mostly hill chieftains, while Kilar were the headmen of settlements ...

- Sinha, Kanchan (1979). Kartikeya in Indian art and literature. Sundeep Prakashan.

- Sivathamby, K. (December 1974), "Early South Indian Society and Economy: The Tinai Concept", Social Scientist, 3 (5): 20–37, doi:10.2307/3516448, JSTOR 3516448,

Those who ruled over small territories were called Kurunilamannar. The area ruled by such a small ruler usually corresponded to a geographical unit. In Purananuru a number of such chieftains are mentioned;..

- "Grand Anaicut", Encyclopædia Britannica, retrieved 3 May 2006

- Narayanan, M. G. S. (September 1988), "The Role of Peasants in the Early History of Tamilakam in South India", Social Scientist, 16 (9): 17–34, doi:10.2307/3517170, JSTOR 3517170

- "Pandya Dynasty", Encyclopædia Britannica, retrieved 3 May 2007

- Veluppillai, A., Archaeologists Uncover Ancient Maritime Spice Route Between India, Egypt

- The term Periplus refers to the region of the eastern seaboard of South India as Damirica – "The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: Travel and Trade in the Indian Ocean by a Merchant of the First Century", Ancient History source book

- Indian Geographical Society (1941), The Indian Geographical Journal, p. 69,

These Kalabhras were thrown out by the powerful Pallava dynasty in the fourth century AD ... this period is aptly known as "Dark Ages" of Tamil Nadu.

- K.A.N. Sastri, A History of South India

- Sastri, K. A. Nilakanta (1955). A History of South India. Oxford University Press. p. 130.

Kalabhraas were denounced as 'evil kings' (kaliararar)

- Sastri, K. A. Nilakanta (1955). A History of South India. Oxford University Press.

- Hirsh, Marilyn (1987), "Mahendravarman I Pallava: Artist and Patron of Mamallapuram", Artibus Asiae, 48 (1/2): 109–130, doi:10.2307/3249854, JSTOR 3249854

- A. Kiruṭṭin̲an̲ (2000). Tamil culture: religion, culture, and literature. Bharatiya Kala Prakashan. p. 17.

- 'Everywhere within Beloved-of-the-Gods, King Piyadasi's domain, and among the people beyond the borders, the Cholas, the Pandyas, the Satyaputras, the Keralaputras, as far as Tamraparni ...' —"Ashoka's second minor rock edict". Colorado State University. Archived from the original on 28 October 2013. Retrieved 15 November 2006.

- "Hathigumpha Inscription". Epigraphia Indica, Vol. XX (1929–1930). Delhi, 1933, pp. 86–89. Missouri Southern State University. Archived from the original on 17 November 2006. Retrieved 15 November 2006.

- Kamil Veith Zvelebil, Companion Studies to the History of Tamil Literature, p. 12

- Chandra, Satish (1997), Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals (1206–1526) – I, Har-Anand Publications, p. 250, ISBN 978-81-241-1064-5,

... Starting from the Tamil lands under the Pallava kings, bhakti spread to different parts of south India ...

- Chopra, P. N.; Ravindran, T. K.; Subrahmanian, N. (2003). History of South India (Ancient, Medieval and Modern) Part 1. New Delhi: Chand Publications. ISBN 978-81-219-0153-6.

- Sastri, K. A. Nilakanta (1955). A History of South India. Oxford University Press. p. 136.

- Sastri, K. A. Nilakanta (1955). A History of South India. Oxford University Press. p. 140.

- Sastri, K. A. Nilakanta (1955). A History of South India. Oxford University Press. p. 162.

- Srivastava, Balram (1973), Rajendra Chola, National Book Trust, India, p. 80,

The mission which Rajendra sent to China was essentially a trade mission, ...

- Curtin, Philip D. (1984), Cross-Cultural Trade in World History, Cambridge University Press, p. 101, ISBN 978-0-521-26931-5

- Smith, Vincent Arthur (1904), The Early History of India, The Clarendon press, pp. 336–58, ISBN 978-81-7156-618-1

- The Cambridge Shorter History of India. CUP Archive. p. 191.

- Sen, Sailendra Nath (1999). Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International. p. 485.

- Singapore in Global History by Derek Thiam Soon Heng, Syed Muhd Khairudin Aljunied p.40

- Hermann Kulke; K Kesavapany; Vijay Sakhuja (2009). Nagapattinam to Suvarnadwipa: Reflections on the Chola Naval Expeditions to Southeast Asia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 11–12.

- K. A. N. Sastri (1955). The Cōḷas. University of Madras. p. 301.

- S. Jeyaseela Stephen, ed. (2008). The Land, Peasantry, and Peasant Life in India New Direction, Renewed Debate. Manak Publications. p. 87.

- Sailendra Nath Sen. Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International, 1999. p. 487.

- Sailendra Nath Sen. Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International, 1999. p. 459.

- Burton Stein (1990). The New Cambridge History of India Vijayanagara Volume 1. Cambridge University Press. p. 57.

- P. K. S. Raja (1966). Mediaeval Kerala. Navakerala Co-op Publishing House. p. 47.

- Ē. Kē Cēṣāttiri (1998). Sri Brihadisvara, the Great Temple of Thanjavur. Nile Books. p. 24.

- Heather Elgood (2000). Hinduism and the Religious Arts. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 162.

- Freeman, Rich (February 1998), "Rubies and Coral: The Lapidary Crafting of Language in Kerala", The Journal of Asian Studies, 57 (1): 38–65, doi:10.2307/2659023, JSTOR 2659023, S2CID 162294036 at pp. 41–43.

- Subrahmanian, N. (1993). Social and cultural history of Tamilnad. Ennes. p. 209.

- Paniker, K. Ayyappa (1997). Medieval Indian Literature: Surveys and selections. Sahitya Akademi. pp. 299–300. ISBN 9788126003655.

- de Silva 2005, p. 129

- Natarajan, V., History of Ceylon Tamils, p. 9

- Indrapala, K. The Evolution of an ethnic identity: The Tamils of Sri Lanka, pp. 53–54

- South Asia Association (1987), "Volumes 7–8", South Asia Bulletin, University of California, Los Angeles

- de Silva 1997, p. 129

- Indrapala, K. The Evolution of an ethnic identity: The Tamils of Sri Lanka, p. 91

- Subramanian, T.S. (27 January 2006), "Reading the past in a more inclusive way: Interview with Dr. Sudharshan Seneviratne", Frontline, archived from the original on 12 June 2008, retrieved 9 July 2008

- Tambiah, Stanley Jeyaraja (1986). Sri Lanka: Ethnic Fratricide and the Dismantling of Democracy. I.B.Tauris. p. 90. ISBN 9781850430261.

- Ragupathy, Ponnampalam (1987). Early Settlements in Jaffna: An Archaeological Survey. University of Jaffna. p. 223.

- Mahadeva, I. Early Tamil Epigraphy: From the Earliest Times to the Sixth Century A.D., p. 48

- Indrapala, K., The Evolution of an ethnic identity: The Tamils of Sri Lanka, p. 157

- de Silva 1997, pp. 30–32

- Mendis, G.C. Ceylon Today and Yesterday, pp. 24–25

- Nadarajan, V., History of Ceylon Tamils, p. 40

- Spencer, George W (1976), "The politics of plunder: The Cholas in eleventh century Ceylon", The Journal of Asian Studies, 35 (3): 405–419, doi:10.2307/2053272, JSTOR 2053272, S2CID 154741845

- Indrapala, K The Evolution of an ethnic identity: The Tamils of Sr Lanka, pp. 214–15

- de Silva 1997, pp. 46, 48, 75

- de Silva 1997, p. 76

- de Silva 1997, pp. 100–02

- de Silva 1997, pp. 102–04

- de Silva 1997, p. 104

- Knox, Robert (1681), An Historical Relation of the Island Ceylon, London: Robert Chiswell, p. 166, ISBN 978-1-4069-1141-1, 2596825

- Upon arrival in June 1799, Sir Hugh Cleghorn, the island's first British colonial secretary, wrote to the British government of the traits and antiquity of the Tamil nation on the island in the Cleghorn Minute: "Two different nations from a very ancient period have divided between them the possession of the island. First the Sinhalese, inhabiting the interior in its Southern and Western parts, and secondly the Malabars [another name for Tamils] who possess the Northern and Eastern districts. These two nations differ entirely in their religion, language, and manners." McConnell, D., 2008; Ponnambalam, S. 1983

- de Silva 1997, p. 121

- Spencer, Sri Lankan history and roots of conflict, p. 23

- Indrapala, K., The Evolution of an ethnic identity: The Tamils of Sri Lanka, p. 275

- Stokke, K. (2006). "Building the Tamil Eelam State: emerging state institutions and forms of governance in LTTE-controlled areas in Sri Lanka". Third World Quarterly. 27 (6): 1021–40. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.466.5940. doi:10.1080/01436590600850434. S2CID 45544298.

- McConnell, D. (2008). "The Tamil people's right to self-determination". Cambridge Review of International Affairs. 21 (1): 59–76. doi:10.1080/09557570701828592. S2CID 154770852.

- Donald L. Horowitz, Ethnic Groups in Conflict

- Sri Lanka: Current Issues and Historical Background (2002), Walter Nubin, p. 87

- Tambiah, Stanley (1984). Sri Lanka: Ethnic Fratricide and the Dismantling of Democracy. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-78952-1.

- "Up to 100,000 killed in Sri Lanka's civil war: UN". ABC News. 20 May 2009. Retrieved 1 March 2016.

- "Sri Lanka: New Evidence of Wartime Abuses". Human Rights Watch. 20 May 2010. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- "Almost 5 million Tamils live outside Tamil Nadu, inside India". Censusindia.gov.in. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- de Silva 1997, pp. 177, 181

- de Silva 1987, pp. 3–5, 9.

- Department of Census and Statistics of Sri Lanka, Population by Ethnicity according to District (PDF), statistics.gov.lk, retrieved 3 May 2007

- V. Suryanarayan (2001), "In search of a new identity", Frontline, archived from the original on 29 May 2008, retrieved 2 July 2008

- de Silva 1997, p. 262

- Christophe Z Guilmoto (1993), "The Tamil Migration Cycle 1830–1950", Economic and Political Weekly, Economic and Political Weekly, 28 (3): 111–20, JSTOR 4399307

- Tamil diaspora – a trans state nation, Tamilnation.org, archived from the original on 21 July 2011, retrieved 4 December 2006

- Shahbazi, Ammar (20 March 2012). "Strangers to their roots, and those around them". The News. Archived from the original on 17 June 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- McDowell, Chris (1996), A Tamil Asylum Diaspora: Sri Lankan Migration, Settlement and Politics in Switzerland, New York: Berghahn Books, ISBN 978-1-57181-917-8

- "New Beginnings: Tamil Heritage in Toronto". Heritagetoronto.org. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- See Sumathi Ramasamy, Passions of the Tongue, 'Feminising language: Tamil as Goddess, Mother, Maiden' Chapter 3.

- (Ramaswamy 1998)

- Kailasapathy, K. (1979), "The Tamil Purist Movement: A Re-Evaluation", Social Scientist, 7 (10): 23–51, doi:10.2307/3516775, JSTOR 3516775

- Hart, G. L. (1975). The Poems of Ancient Tamil: Their Milieu and their Sanskrit Counterparts. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-02672-1.

- Manguin, Pierre-Yves; Mani, A.; Wade, Geoff (2011). Early Interactions Between South and Southeast Asia: Reflections on Cross-cultural Exchange. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 138. ISBN 9789814345101.

- Thiruchandran, Selvy (1997). Ideology, caste, class, and gender. Vikas Pub. House.

- Lal, Mohan (2006). The Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature (Volume Five Sasay To Zorgot), Volume 5. Sahitya Akademi. p. 4396. ISBN 978-81-260-1221-3.

- "Census 2001 – Statewise population by Religion". Censusindia.gov.in. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- More, J.B.P. (2007), Muslim identity, print culture and the Dravidian factor in Tamil Nadu, Hyderabad: Orient Longman, ISBN 978-81-250-2632-7 at p. xv

- Jain, Dhanesh (2003), "Sociolinguistics of the Indo-Aryan languages", in Cardona, George; Jain, Dhanesh (eds.), The Indo-Aryan Languages, Routledge language family series, London: Routledge, pp. 46–66, ISBN 978-0-7007-1130-7 at p. 57.

- The total number of Jains in Tamil Nadu was 88,000 in 2001. Directorate of Census Operations – Tamil Nadu, Census, archived from the original on 30 November 2006, retrieved 5 December 2006

- Maloney, Clarence (1975), "Religious Beliefs and Social Hierarchy in Tamiḻ Nāḍu, India", American Ethnologist, 2 (1): 169–91, doi:10.1525/ae.1975.2.1.02a00100 at p. 178

- M. Shanmugam Pillai, "Murukan in Cankam Literature: Veriyattu Tribal Worship", First International Conference Seminar on Skanda-Murukan in Chennai, 28–30 December 1998. This article first appeared in the September 1999 issue of The Journal of the Institute of Asian Studies, retrieved 6 December 2006

- Harold G. Coward, John R. Hinnells, Raymond Brady Williams, The South Asian Religious Diaspora in Britain, Canada, and the United States

- "Principles and Practice of Hindu Religion", Hindu Heritage Study Program, archived from the original on 14 November 2006, retrieved 5 December 2006

- P. K. Balachandran, "Tracing the Sri Lanka-Kerala link", Hindustan Times, 23 March 2006, archived from the original on 10 December 2006, retrieved 5 December 2006

- Dr. R. Ponnus, Sri Vaikunda Swamigal and the Struggle for Social Equality in South India, (Madurai Kamaraj University) Ram Publishers, p. 98

- Abraham, George (28 December 2020). Lanterns on the Lanes: Lit for Life…. Notion Press. ISBN 978-1-64899-659-7.

- Shashi, S.S. (1996). Encyclopaedia Indica: India, Pakistan, Bangladesh: Volume 100. Anmol Publications.

- Subramanium, N. (1980). Śaṅgam polity: the administration and social life of the Śaṅgam Tamils. Ennes Publications.

- Mark Jarzombek (2009), "Horse Shrines in Tamil India: Reflections on Modernity" (PDF), Future Anterior, 4 (1): 18–36, doi:10.1353/fta.0.0031, S2CID 191627473

- "'Hero stone' unearthed", The Hindu, Chennai, India, 22 July 2006, archived from the original on 1 October 2007, retrieved 5 December 2006

- Swamy, Subramanian (18 March 2004), "Redefining secularism", The Hindu, Chennai, India, archived from the original on 27 May 2004, retrieved 5 December 2006

- Jaina Literature in Tamil, Prof. A. Chakravartis

- "The Milieu of the Ancient Tamil Poems, Prof. George Hart". 9 July 1997. Archived from the original on 9 July 1997. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- Zarrilli, Phillip B. (1992) "To Heal and/or To Harm: The Vital Spots in Two South Indian Martial Traditions"

- "Martial Arts in India". Sports.indiapress.org. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- South Asian Folklore: An Encyclopedia : Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka(2003), p. 386.

- Ethnic Insurgency and National Integration: A Study of Selected Ethnic Problems in South Asia (1997) p. 114

- Sri Lankan Ethnic Crisis: Towards a Resolution (2002), p. 76.

- Sharada Srinivasan; Srinivasa Ranganathan (2004). India's Legendary Wootz Steel: An Advanced Material of the Ancient World. National Institute of Advanced Studies. OCLC 82439861. Archived from the original on 11 February 2019. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- Ward, Gerald W. R. The Grove Encyclopedia of Materials and Techniques in Art. p. 380.

- Sharada Srinivasan (1994). Wootz crucible steel: a newly discovered production site in South India. Papers from the Institute of Archaeology 5(1994) 49–59 doi:10.5334/pia.60

- Herbert Henery Coghlan. (1977). Notes on prehistoric and early iron in the Old World. pp 99–100

- B. Sasisekharan (1999).TECHNOLOGY OF IRON AND STEEL IN KODUMANAL- Archived 1 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Hilda Ellis Davidson. The Sword in Anglo-Saxon England: Its Archaeology and Literature. p. 20

- Burton, Sir Richard Francis (1884). The Book of the Sword. Internet archive: Chatto and Windus. p. 111. ISBN 978-1-60520-436-9.

- Needham, Volume 4, Part 1, p. 282.

- Manning, Charlotte Speir. Ancient and Medieval India. Volume 2. ISBN 978-0-543-92943-3.

- Hobbies – Volume 68, Issue 5, p. 45. Lghtner Publishing Company (1963)

- Mahathevan, Iravatham (24 June 2010). "An epigraphic perspective on the antiquity of Tamil". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 1 July 2010. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- "Dinithi Volume 1 Issue 4" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 September 2013. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- Manning, Charlotte Speir. Ancient and Mediæval India. Volume 2. ISBN 978-0-543-92943-3.

- Coomaraswamy, A. K. (1946). Figures of Speech or Figures of Thought. Luzac & Co.

- "Tanjore – Painting", tanjore.net, Tanjore.net, archived from the original on 27 November 2006, retrieved 4 December 2006

- Nayanthara, S. (2006), The World of Indian murals and paintings, Chillbreeze, ISBN 978-81-904055-1-5 at pp. 55–57

- "Shilpaic literature of the tamils", V. Ganapathi, INTAMM, retrieved 4 December 2006

- Aschwin Lippe (December 1971), "Divine Images in Stone and Bronze: South India, Chola Dynasty (c. 850–1280)", Metropolitan Museum Journal, 4: 29–79, doi:10.2307/1512615, JSTOR 1512615, S2CID 192943206,

The bronze icons of Early Chola period are one of India's greatest contribution to world art ...

- Heaven sent: Michael Wood explores the art of the Chola dynasty, Royal Academy, UK, archived from the original on 3 March 2007, retrieved 26 April 2007

- Berkson, Carmel (2000), "II The Life of Form pp. 29–65", The Life of Form in Indian Sculpture, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 978-81-7017-376-2

- Sivaram, Rama (1994). Early Chola Art: Origin and Emergence of Style. Navrang. ISBN 81-7013-079-4.

- Nijenhuis, Emmie te (1974), Indian Music: History and Structure, Leiden: Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-03978-0 at pp. 4–5

- Widdess, D.R. (1979), "The Kudumiyamalai inscription: a source of early Indian music in notation", in Picken, Laurence (ed.), Musica Asiatica, vol. 2, London: Oxford University Press, pp. 115–50

- Leslie, Julia (1992). Roles and rituals for Hindu women. South Asia Books. pp. 149–152. ISBN 978-81-208-1036-5.

- Sharma, Manorama (2004). Folk India: A Comprehensive Study of Indian Folk Music and Culture, Vol. 11

- "Therukoothu". Tamilnadu.com. 16 February 2013. Archived from the original on 11 April 2013.

- Tamil Art History, eelavar.com, archived from the original on 27 April 2006, retrieved 5 December 2006

- "Bhagavata mela", The Hindu, Chennai, India, 30 April 2004, archived from the original on 13 November 2004, retrieved 5 December 2006

- Dennis Kennedy "The Oxford Encyclopedia of Theatre and Performance, Publisher:Oxford University Press

- Templeton, Tom (26 November 2006), "The states they're in", Guardian, London, retrieved 5 December 2006

- "Eros buys Tamil film distributor", Business Standard, 6 October 2011

- Gautier, François (2001), A Western Journalist on India: The Ferengi's Columns, ISBN 978-81-241-0795-9

- Grushkin, Daniel (22 March 2007), "NY Times: The ritual dates back as far as 2,000 years ...", The New York Times, retrieved 24 May 2007

- International Sport Management. Human Kinetics. May 2010. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-7360-8273-0. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- "Traditional martial arts not given due importance". newstodaynet.com. Archived from the original on 22 January 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- Historical Dictionary of the Tamils, Vijaya Ramaswamy, Scarecrow Press, 22 May 2007.

- Mangoes & Curry Leaves: Culinary Travels Through the Great Subcontinent, Jeffrey Alford, Naomi Duguid, Artisan Books, 1 November 2005, p. 146.

Sources

- de Silva, Chandra Richard (1997), Sri Lanka – A History (2, illustrated ed.), Vikas Pub. House, ISBN 978-0-9510710-2-1

- de Silva, K. M. (2005), A History of Sri Lanka, Colombo: Vijitha Yapa, ISBN 978-955-8095-92-8

- Gadgil, M. & Joshi, N.V. & Shambu Prasad, U.V. & Manoharan, S. & Patil, S. (1997). "Peopling of India." In D. Balasubramanian and N. Appaji Rao (eds.), The Indian Human Heritage, pp. 100–129. Hyderabad: Universities Press. ISBN 81-7371-128-3.

- Mark Jarzombek, "Horse Shrines in Tamil India: Reflections on Modernity", Future Anterior, (4/1), pp 18–36.

- Mahadevan, Iravatham (2003). Early Tamil Epigraphy from the Earliest Times to the Sixth Century A.D. Cambridge, Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01227-5.

- Pillai, Suresh B. (1976). Introduction to the study of temple art. Thanjavur: Equator and Meridian.

- Ramaswamy, Sumathi (1998). Passions of the Tongue: language devotion in Tamil India 1891–1970. Delhi: Munshiram. ISBN 81-215-0851-7.

- Sastri, K.A. Nilakanta (2002) [1955], A history of South India from prehistoric times to the fall of Vijayanagar, New Delhi: Indian Branch, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-560686-7

- Sastri, K.S. Ramaswamy (2002). The Tamils: The People, Their History and Culture, Vol. 1: An Introduction to Tamil History and Society. New Delhi: Cosmo Publications. ISBN 81-7755-406-9.

- Sharma, Manorama (2004). Folk India: A Comprehensive Study of Indian Folk Music and Culture, Vol. 11: Tamil Nadu and Kerala. New Delhi: Sundeep Prakashan. ISBN 81-7574-141-4.

- Steever, Sanford (1998), Steever, Sanford (ed.), The Dravidian Languages, London: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-10023-6

- Subramanian, T.S. (17 February 2005), "'Rudimentary Tamil-Brahmi script' unearthed at Adichanallur", The Hindu, Chennai, India, archived from the original on 17 February 2005

- Wells, Spencer (2004). The Journey of Man : A Genetic Odyssey. New York, NY: Random House Trade Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-8129-7146-0.

- Patil, S. (1997). "Peopling of India." In D. Balasubramanian and N. Appaji Rao (eds.), The Indian Human Heritage.

Further reading

- Bowers, F. (1956). Theatre in the East – A Survey of Asian Dance and Drama. Grove Press.

- Chaitanya, Krishna (1971). A history of Malayalam literature. Orient Longman. ISBN 81-250-0488-2.

- Hart, G. L. (1979). "The Nature of Tamil Devotion". In Deshpande, M. M.; Hook, P. E. (eds.). Aryan and Non-Aryan in India. Ann Arbor. pp. 11–33. ISBN 0-89148-014-5.

- Hart, G. L. (1987). "Early Evidence for Caste in South India". In Hockings, P. (ed.). Dimensions of Social Life: Essays in honor of David B. Mandelbaum. Mouton Gruyter.

- Keay, John (2000). India: A History. New York: Grove Publications. ISBN 978-0-8021-3797-5.

- Varadpande, M. L. (1992). Loka Ranga: Panorama of Indian Folk Theatre. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 81-7017-278-0.

- Zvebil, K. (1974). The Smile of Murugan: On Tamil Literature of South India. Brill. ISBN 90-04-03591-5.