Trade winds

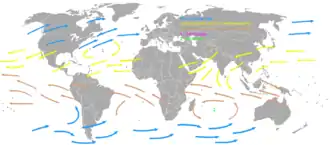

The trade winds or easterlies are the permanent east-to-west prevailing winds that flow in the Earth's equatorial region. The trade winds blow mainly from the northeast in the Northern Hemisphere and from the southeast in the Southern Hemisphere, strengthening during the winter and when the Arctic oscillation is in its warm phase. Trade winds have been used by captains of sailing ships to cross the world's oceans for centuries. They enabled colonial expansion into the Americas, and trade routes to become established across the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean.

In meteorology, they act as the steering flow for tropical storms that form over the Atlantic, Pacific, and southern Indian oceans and make landfall in North America, Southeast Asia, and Madagascar and East Africa. Shallow cumulus clouds are seen within trade wind regimes and are capped from becoming taller by a trade wind inversion, which is caused by descending air aloft from within the subtropical ridge. The weaker the trade winds become, the more rainfall can be expected in the neighboring landmasses.

The trade winds also transport nitrate- and phosphate-rich Saharan dust to all Latin America, the Caribbean Sea, and to parts of southeastern and southwestern North America. Sahara dust is on occasion present in sunsets across Florida. When dust from the Sahara travels over land, rainfall is suppressed and the sky changes from a blue to a white appearance which leads to an increase in red sunsets. Its presence negatively impacts air quality by adding to the count of airborne particulates.[1]

History

The term originally derives from the early fourteenth century sense of trade (in late Middle English) still often meaning "path" or "track".[2] The Portuguese recognized the importance of the trade winds (then the volta do mar, meaning in Portuguese "turn of the sea" but also "return from the sea") in navigation in both the north and south Atlantic Ocean as early as the 15th century.[3] From West Africa, the Portuguese had to sail away from continental Africa, that is, to west and northwest. They could then turn northeast, to the area around the Azores islands, and finally east to mainland Europe. They also learned that to reach South Africa, they needed to go far out in the ocean, head for Brazil, and around 30°S go east again. (This is because following the African coast southbound means sailing upwind in the Southern hemisphere.) In the Pacific Ocean, the full wind circulation, which included both the trade wind easterlies and higher-latitude westerlies, was unknown to Europeans until Andres de Urdaneta's voyage in 1565.[4]

The captain of a sailing ship seeks a course along which the winds can be expected to blow in the direction of travel.[5] During the Age of Sail, the pattern of prevailing winds made various points of the globe easy or difficult to access, and therefore had a direct effect on European empire-building and thus on modern political geography. For example, Manila galleons could not sail into the wind at all.[4]

By the 18th century, the importance of the trade winds to England's merchant fleet for crossing the Atlantic Ocean had led both the general public and etymologists to identify the name with a later meaning of "trade": "(foreign) commerce".[6] Between 1847 and 1849, Matthew Fontaine Maury collected enough information to create wind and current charts for the world's oceans.[7]

Cause

As part of the Hadley cell, surface air flows toward the equator while the flow aloft is towards the poles. A low-pressure area of calm, light variable winds near the equator is known as the doldrums,[8] near-equatorial trough,[9] intertropical front, or the Intertropical Convergence Zone.[10] When located within a monsoon region, this zone of low pressure and wind convergence is also known as the monsoon trough.[11] Around 30° in both hemispheres, air begins to descend toward the surface in subtropical high-pressure belts known as subtropical ridges. The subsident (sinking) air is relatively dry because as it descends, the temperature increases, but the moisture content remains constant, which lowers the relative humidity of the air mass. This warm, dry air is known as a superior air mass and normally resides above a maritime tropical (warm and moist) air mass. An increase of temperature with height is known as a temperature inversion. When it occurs within a trade wind regime, it is known as a trade wind inversion.[12]

The surface air that flows from these subtropical high-pressure belts toward the Equator is deflected toward the west in both hemispheres by the Coriolis effect.[13] These winds blow predominantly from the northeast in the Northern Hemisphere and from the southeast in the Southern Hemisphere.[14] Because winds are named for the direction from which the wind is blowing,[15] these winds are called the northeasterly trade winds in the Northern Hemisphere and the southeasterly trade winds in the Southern Hemisphere. The trade winds of both hemispheres meet at the Doldrums.[8]

As they blow across tropical regions, air masses heat up over lower latitudes due to more direct sunlight. Those that develop over land (continental) are drier and hotter than those that develop over oceans (maritime), and travel northward on the western periphery of the subtropical ridge.[16] Maritime tropical air masses are sometimes referred to as trade air masses.[17] All tropical oceans except the northern Indian Ocean have extensive areas of trade winds.[18]

Weather and biodiversity effects

Clouds which form above regions within trade wind regimes are typically composed of cumulus which extend no more than 4 kilometres (13,000 ft) in height, and are capped from being taller by the trade wind inversion.[19] Trade winds originate more from the direction of the poles (northeast in the Northern Hemisphere, southeast in the Southern Hemisphere) during the cold season, and are stronger in the winter than the summer.[20] As an example, the windy season in the Guianas, which lie at low latitudes in South America, occurs between January and April.[21] When the phase of the Arctic oscillation (AO) is warm, trade winds are stronger within the tropics. The cold phase of the AO leads to weaker trade winds.[22] When the trade winds are weaker, more extensive areas of rain fall upon landmasses within the tropics, such as Central America.[23]

During mid-summer in the Northern Hemisphere (July), the westward-moving trade winds south of the northward-moving subtropical ridge expand northwestward from the Caribbean sea into southeastern North America (Florida and Gulf Coast). When dust from the Sahara moving around the southern periphery of the ridge travels over land, rainfall is suppressed and the sky changes from a blue to a white appearance which leads to an increase in red sunsets. Its presence negatively impacts air quality by adding to the count of airborne particulates.[1] Although the Southeast USA has some of the cleanest air in North America, much of the African dust that reaches the United States affects Florida.[24] Since 1970, dust outbreaks have worsened due to periods of drought in Africa. There is a large variability in the dust transport to the Caribbean and Florida from year to year.[25] Dust events have been linked to a decline in the health of coral reefs across the Caribbean and Florida, primarily since the 1970s.[26]

Every year, millions of tons of nutrient-rich Saharan dust cross the Atlantic Ocean, bringing vital phosphorus and other fertilizers to depleted Amazon soils.[27]

See also

- Intertropical Convergence Zone

- Volta do mar

- Westerly wind burst

- Winds in the Age of Sail

References

- Science Daily (1999-07-14). African Dust Called A Major Factor Affecting Southeast U.S. Air Quality. Retrieved on 2007-06-10.

- Carol G. Braham; Enid Pearsons; Deborah M. Posner; Georgia S. Maas & Richard Goodman (2001). Random House Webster's College Dictionary (second ed.). Random House. p. 1385. ISBN 978-0-375-42560-8.

- Hermann R. Muelder (2007). Years of This Land - A Geographical History of the United States. Read Books. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-4067-7740-6.

- Derek Hayes (2001). Historical atlas of the North Pacific Ocean: maps of discovery and scientific exploration, 1500–2000. Douglas & McIntyre. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-55054-865-5.

- Cyrus Cornelius Adams (1904). A text-book of commercial geography. D. Appleton and company. p. 19.

- Oxford English Dictionary (2 ed.). p. 225.

- Derek Hayes (2001). Historical atlas of the North Pacific Ocean: maps of discovery and scientific exploration, 1500–2000. Douglas & McIntyre. p. 152. ISBN 978-1-55054-865-5.

- Sverre Petterssen (1941). Introduction to Meteorology. Mcgraw-Hill Book Company, Inc. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-4437-2300-8.

- Glossary of Meteorology (June 2000). "Doldrums". American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2009-09-25. Retrieved 2009-11-09.

- Glossary of Meteorology (June 2000). "Intertropical Convergence Zone". American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2009-06-02. Retrieved 2009-11-09.

- Glossary of Meteorology (June 2000). "Monsoon Trough". American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2009-06-17. Retrieved 2009-11-09.

- Glossary of Meteorology (June 2000). "Superior air". American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2009-10-28.

- Glossary of Meteorology (2009). "trade winds". Glossary of Meteorology. American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2008-12-11. Retrieved 2008-09-08.

- Ralph Stockman Tarr; Frank Morton McMurry; Almon Ernest Parkins (1909). Advanced geography. State Printing. p. 246.

- JetStream (2008). "How to read weather maps". National Weather Service. Archived from the original on 2012-07-05. Retrieved 2007-05-16.

- Glossary of Meteorology (June 2000). "Tropical air". American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2009-10-28.

- Glossary of Meteorology (June 2000). "Trade air". American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2009-10-28.

- John E. Oliver (2005). Encyclopedia of world climatology. Springer. p. 128. ISBN 978-1-4020-3264-6.

- Bob Rauber (2009-05-22). "Research-The Rain in Cumulus over the Ocean Campaign". Retrieved 2009-11-08.

- James P. Terry (2007). Tropical cyclones: climatology and impacts in the South Pacific. Springer. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-387-71542-1.

- G. E. Pieter & F. Augustinus (2004). "The influence of the trade winds on the coastal development of the Guianas at various scale levels: a synthesis". Marine Geology. 208 (2–4): 145–151. Bibcode:2004MGeol.208..145A. doi:10.1016/j.margeo.2004.04.007. hdl:1874/12170.

- Robert R. Steward (2005). "The Ocean's Influence on North American Drought". Texas A&M University.

- John E. Oliver (2005). Encyclopedia of world climatology. Springer. p. 185. ISBN 978-1-4020-3264-6.

- Science Daily (2001-06-15). Microbes And The Dust They Ride In On Pose Potential Health Risks. Retrieved on 2007-06-10.

- Usinfo.state.gov (2003). Study Says African Dust Affects Climate in U.S., Caribbean. Archived 2007-06-20 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 2007-06-10.

- U. S. Geological Survey (2006). Coral Mortality and African Dust. Retrieved on 2007-06-10.

- Yu, Hongbin; Chin, Mian; Yuan, Tianle; Bian, Huisheng; Remer, Lorraine A.; Prospero, Joseph M.; Omar, Ali; Winker, David; Yang, Yuekui; Zhang, Yan; Zhang, Zhibo; Zhao, Chun (2015). "The fertilizing role of African dust in the Amazon rainforest: A first multiyear assessment based on data from Cloud‐Aerosol Lidar and Infrared Pathfinder Satellite Observations". Geophysical Research Letters. 42 (6): 1984–1991. Bibcode:2015GeoRL..42.1984Y. doi:10.1002/2015GL063040.

- "Massive amounts of Saharan dust fertilize the Amazon rainforest". ScienceDaily (Press release). February 24, 2015.