Juneau, Alaska

The City and Borough of Juneau, more commonly known simply as Juneau (/ˈdʒuːnoʊ/ JOO-noh; Tlingit: Dzánti K'ihéeni [ˈtsʌ́ntʰɪ̀ kʼɪ̀ˈhíːnɪ̀]), is the capital city of the state of Alaska. Located in the Gastineau Channel and the Alaskan panhandle, it is a unified municipality and the second-largest city in the United States by area. Juneau was named the capital of Alaska in 1906, when the government of what was then the District of Alaska was moved from Sitka as dictated by the U.S. Congress in 1900.[3][4] The municipality unified on July 1, 1970, when the city of Juneau merged with the city of Douglas and the surrounding Greater Juneau Borough to form the current municipality,[5] which is larger by area than both Rhode Island and Delaware.

Juneau, Alaska

Dzánti K'ihéeni | |

|---|---|

Top to bottom: Downtown, Alaska State Capitol, National Shrine of St. Thérèse, St. Nicholas Russian Orthodox Church, Juneau-Douglas Bridge | |

Flag  Seal | |

Juneau Location within Alaska  Juneau Location within North America  Juneau Juneau (North America) | |

| Coordinates: 58.30°N 134.416°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Alaska |

| Named | 1881 (Juneau City) 1882 (Juneau) |

| Incorporated | 1900 |

| Home-rule city | October 1960 |

| Borough | September 30, 1963 (Greater Juneau Borough) July 1, 1970 (City and Borough of Juneau) |

| Founded by | Richard Harris and Joe Juneau |

| Named for | Joe Juneau |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Beth Weldon |

| • Governing body | Assembly |

| • State senator | Jesse Kiehl (D) |

| • State reps. | Sara Hannan (D) Andi Story (D) |

| Area | |

| • State capital city | 3,254.70 sq mi (8,429.64 km2) |

| • Land | 2,704.03 sq mi (7,003.41 km2) |

| • Water | 550.67 sq mi (1,426.23 km2) |

| • Urban | 14.0 sq mi (36 km2) |

| Elevation | 56 ft (17 m) |

| Population (2020)[2] | |

| • State capital city | 32,255 |

| • Density | 11.93/sq mi (4.61/km2) |

| • Urban | 24,537 |

| • Urban density | 1,749.5/sq mi (675.5/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−9 (AKST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−8 (AKDT) |

| ZIP code | 99801-99803, 99811-99812, 99821, 99824 |

| Area code | 907 |

| FIPS code | 02-36400 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1404263 |

| Website | www |

Downtown Juneau (58°18′00″N 134°24′58″W) is nestled at the base of Mount Juneau and across the channel from Douglas Island. As of the 2020 census, the City and Borough had a population of 32,255,[2] making it the third-most populous city in Alaska after Anchorage and Fairbanks. Juneau experiences a daily influx of roughly 6,000 people from visiting cruise ships between the months of May and September.

The city is named after a gold prospector from Quebec, Joe Juneau, though the place was once called Rockwell and then Harrisburg (after Juneau's co-prospector, Richard Harris). The Tlingit name of the town is Dzántik'i Héeni ("Base of the Flounder's River," dzánti 'flounder,' –kʼi 'base,' héen 'river'), and Auke Bay just north of Juneau proper is called Áak'w ("Little lake," áa 'lake,' -kʼ 'diminutive') in Tlingit. The Taku River, just south of Juneau, was named after the cold t'aakh wind, which occasionally blows down from the mountains.

Juneau is unique among the 49 U.S. capitals on mainland North America in that there are no roads connecting the city to the rest of the state or North America. Honolulu, Hawaii, is the only other state capital not connected by road to the rest of North America. The absence of a road network is due to the extremely rugged terrain surrounding the city. This in turn makes Juneau a de facto island city in terms of transportation, since all goods coming in and out must go by plane or boat, in spite of the city's location on the Alaskan mainland. Downtown Juneau sits at sea level, with tides averaging 16 feet (5 m), below steep mountains about 3,500 to 4,000 feet (1,100 to 1,200 m) high. Atop these mountains is the Juneau Icefield, a large ice mass from which about 30 glaciers flow; two of these, the Mendenhall Glacier and the Lemon Creek Glacier, are visible from the local road system. The Mendenhall glacier has been gradually retreating; its front face is declining in width and height.

The Alaska State Capitol in downtown Juneau was built as the Federal and Territorial Building in 1931. Prior to statehood, it housed federal government offices, the federal courthouse and a post office. It also housed the territorial legislature and many other territorial offices, including that of the governor. Today, Juneau remains the home of the state legislature and the offices of the governor and lieutenant governor. Some other executive branch offices have moved elsewhere in the state.

History

Long before European settlement in the Americas, the Gastineau Channel was a fishing ground for the Auke (A'akw Kwáan) and Taku tribes, who had inhabited the surrounding area for thousands of years. The A'akw Kwáan had a village and burying ground here. In the 21st century it is known as Indian Point. They annually harvested herring during the spawning season.

Since the late 20th century, the A'akw Kwáan, together with the Sealaska Heritage Institute, have resisted European-American development of Indian Point, including proposals by the National Park Service and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). They consider it sacred territory, both because of the burying ground and the importance of the point in their traditions of gathering sustenance from the sea. They continue to gather clams, gumboot chitons, grass and sea urchins there, as well as tree bark for medicinal uses.[6] The city and state supported Sealaska Heritage Institute in documenting the 78 acres (32 ha) site, and, in August 2016, it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. "It is the first traditional cultural property in Southeast Alaska to be placed on the register."[6][7]

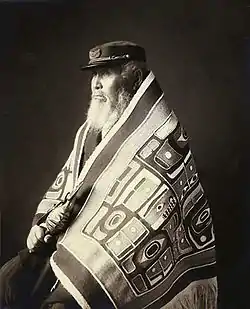

Descendants of these indigenous cultures include the Tlingit people. Native cultures have rich artistic traditions expressed in carving, weaving, orating, singing, and dancing. Juneau has become a major social center for the Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian of Southeast Alaska.

European encounters

Although the Russians had a colony in the Alaska territory from 1784 to 1867, they did not settle in Juneau. They conducted extensive fur trading with Alaskan Natives of the Aleutian Islands and Kodiak.

The first European to see the Juneau area was Joseph Whidbey, master of the Discovery during George Vancouver's 1791–95 expedition. He and his party explored the region in July–August 1794. Early in August he viewed the length of Gastineau Channel from the south, noting a small island in mid-channel. He later recorded seeing the channel again, this time from the west. He said it was unnavigable, being filled with ice.[8]

Mining era

After the California gold rush, miners migrated up the Pacific Coast and explored the West, seeking other gold deposits. In 1880, Sitka mining engineer George Pilz offered a reward to any local native in Alaska who could lead him to gold-bearing ore. A local native arrived with some ore, and several prospectors were sent to investigate. On their first trip to Gold Creek, they found deposits of little interest. However, Pilz sent Joe Juneau (cousin of Milwaukee co-founder Solomon Juneau) and Richard Harris back to the Gastineau Channel, directing them to Snow Slide Gulch (the head of Gold Creek). According to the Rev. Samuel Young, in his book Alaska Days with John Muir, it was their party's campsite at the creek head that Juneau and Harris decided to explore, in the summer of 1879. There they found nuggets "as large as peas and beans," in Harris' words.

On October 18, 1880, the two men marked a 160-acre (650,000 m2) town site where soon a mining camp sprang up. Within a year, so many miners had arrived that the camp became a village, albeit made up mostly of tents and shacks rather than substantial buildings. It was the first European American settlement founded in this territory after the United States purchased Alaska.

By the autumn of 1881, the village had a population of over 100 and was known as Rockwell, after Lt. Com. Charles Rockwell; later it was known as Harrisburg after prospector Richard Harris. On December 14, 1881, a miners' meeting of 72 persons decided to name the settlement Juneau, after prospector Joe Juneau.[9][10]

Establishment of Russian Orthodox Church

Perhaps because of the pressure of this European encroachment, some Tlingit appealed to the Russian Orthodox Church. It had given services in northern Tlingit settlements in local languages since 1800 and 1824. One of its priests had translated scripture and liturgy into the Tlingit language in the 1830s–1840s. The Tlingit arranged for an Orthodox priest to come to their settlement in Juneau. In 1890, some 700 people converted, following chief Yees Gaanaalx and his wife of Auke Bay. The Orthodox Church Missionary Society supported the Tlingit in furnishing and constructing a church for this large congregation.[11]

St. Nicholas Orthodox Church was completed in 1894 and has maintained a strong presence among the Tlingit, Serbians, and other Europeans who followed this church. The iconostasis has six large panels sent from Russia.[11]

Development of mining

During this period, prospector and placer miner John Lemon operated in what is today the Lemon Creek area. The neighborhood that developed there was named for him by early settlers, as have been several other landmarks in Juneau.

Major mining operations in the Juneau mining district prior to World War II included the Treadwell Mine, The Alaska-Juneau Mine, and Alaska-Gastineau Mine.

By 1906, after the decline of whaling and the fur trade, Sitka, the original capital of Alaska, had become less important and the territorial legislature moved the seat of government to Juneau in accordance with a 1900 federal law.[4] Juneau was the largest city in Alaska during the inter-war years, passing Fairbanks in the 1920 census. In the post-World War II years, it was displaced by Anchorage in 1950.

20th and 21st centuries

In 1911, the United States Congress authorized funds for construction of a capitol building for the Alaska Territory. World War I delayed construction and there were difficulties purchasing the necessary land. Citizens of Juneau donated some of the required funds, and construction began on September 8, 1929. Construction of the capitol took less than two years, and the building was dedicated as the Federal and Territorial Building on February 14, 1931. It was designed by Treasury Department architects in the Art Deco architectural style. The building was originally used by the federal government to house the federal courthouse and post office for the territory. Since Alaska gained statehood in 1959, the building has been used by the state government.

The Alaska Governor's Mansion was commissioned under the Public Building Act in 1910. The mansion was designed by James Knox Taylor in the Federal style. Construction was completed in 1912. The territorial governor at that time was the first governor to inhabit the mansion, and he held the first open house for citizens on January 1, 1913. The area of the mansion is 14,400 square feet (1,340 m2). It has ten bathrooms, six bedrooms, and eight fireplaces. The governor resides here when in Juneau on official business. In June 1923, President Warren G. Harding became the first president to visit Alaska. Harding visited the Governor's Mansion while Territorial Governor Scott Bone, who was appointed by Harding, was in office. Harding spoke from the porch of the mansion explaining his policies and met with attendees.

During World War II, more than 50 Japanese citizens and Japanese Americans residing in Juneau were evacuated to the internment camps inland as a result of Executive Order 9066—which authorized the forced removal of all ethnic Japanese away from their homes and businesses on the West Coast of the United States. The removal of Juneau's Japanese community during the war was later commemorated known as the Empty Chair Memorial in July 2014 during a dedication ceremony at the neighborhood of Capital School Park in the city.[12]

Robert Atwood, then publisher of the Anchorage Times and an Anchorage "booster," was an early leader in efforts to move the capital to Fairbanks, which many in both cities resisted. Some supporters of a move wanted a new capital to be at least 30 miles (48 km) from Anchorage and Fairbanks, to prevent either city from having undue influence. Juneau has continued as the capital. In the 1970s, voters passed a plan to move the capital to Willow, a town 70 miles (110 km) north of Anchorage. But pro-Juneau people there and in Fairbanks persuaded voters also to approve a measure (the FRANK Initiative) requiring voter approval of all bondable construction costs before building could begin. Alaskans later voted against spending the estimated $900 million. A 1984 "ultimate" capital-move vote also failed, as did a 1996 vote.

Juneau remains the capital.[13] Once Alaska was granted statehood in 1959, Juneau's population increased along with the growth of state government. After construction of the Alaska Pipeline in 1977, the state budget was flush with oil revenues, and it expanded programs for the people. That growth slowed considerably in the 1980s.[14]

In 2005, the state demographer projected slow growth in the borough for the next twenty years.[15] Cruise ship tourism has expanded rapidly, from approximately 230,000 passengers in 1990 to nearly 1,000,000 in 2006, as cruise lines have built more and larger ships. They sail to Juneau seven days a week over a longer season than before, but the cruising tourism is still primarily a summer industry. It provides few year-round jobs but stimulates summer employment in the city.

In 2010, the city was recognized as part of the "Playful City USA" initiative by KaBOOM!, created to honor cities that ensure their children have great places to play.[16]

Juneau is larger in area than the state of Delaware and was, for many years, the country's largest city by area. Juneau continues to be the only U.S. state capital on an international border: it is bordered on the east by Canada. It is the U.S. state capital whose namesake was most recently alive: Joe Juneau died in 1899,

The city was temporarily renamed UNO, after the card game, on April 1, 2016 (April Fool's Day).[17][18] The change was part of a promotion with Mattel to draw "attention to new wild cards in [the] game".[17] For Juneau's cooperation, Mattel donated $15,000 "to the Juneau Community Foundation in honor of late Mayor Greg Fisk."[17]

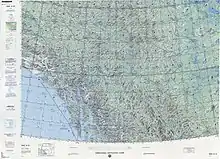

Geography

.jpg.webp)

According to the United States Census Bureau, the borough has an area of 3,255 square miles (8,430 km2), making it the third-largest municipality in the United States by area (the largest is Yakutat City and Borough, Alaska). 2,716.7 square miles (7,036 km2) of it is land and 538.3 square miles (1,394 km2) of it (16.54%) is water.

Central (downtown) Juneau is at 58°18′00″N 134°24′58″W.[19] The City and Borough of Juneau includes Douglas Island, a tidal island to the west of mainland Juneau. Douglas Island can be reached via the Juneau-Douglas Bridge.

As is the case throughout Southeast Alaska, the Juneau area is susceptible to damage caused by natural disasters. The 2014 Palma Bay earthquake caused widespread outages to telecommunications in the area due to damage to a fiber optic cable serving the area. In April 2008, a series of massive avalanches outside Juneau heavily damaged the electrical lines providing Juneau with power, knocking the hydroelectric system offline and forcing the utility to switch to a much more expensive diesel system.

Adjacent boroughs and census areas

- Haines Borough, Alaska – northwest, west

- Hoonah-Angoon Census Area, Alaska – south, southwest

- Petersburg Borough, Alaska – quadripoint

Border area

Juneau, Alaska, shares its eastern border with the Canadian province of British Columbia. It is the only U.S. state capital to border another country.

- Stikine Region, British Columbia – northeast, east

National protected areas

- Tongass National Forest (part)

- Admiralty Island National Monument (part)

- Kootznoowoo Wilderness (part)

- Tracy Arm-Fords Terror Wilderness (part)

- Admiralty Island National Monument (part)

State Parks

Alaska State Parks maintains the Juneau Trail System, a series of wilderness trails ranging from easy to extremely difficult.[20]

Climate

The Juneau area is in a transition zone between a humid continental climate (Köppen Dfb), a subarctic climate (Köppen Dfc), and an oceanic climate (Köppen Cfb/Cfc), depending on the isotherm used. The city's climate is heavily influenced by the proximity of the Pacific Ocean, specifically the warm Alaska Current, and the Coast Mountains that form a natural orographic barrier for incoming air. The weather is thus mild and moist, which, as in other parts of the Alaska Panhandle, allows the growth of temperate rainforests.[21] Like other settlements in the area, Juneau does not experience permafrost.[22]

There are two prevalent types of wind in Juneau. Particularly in winter, the Aleutian Low will draw warm and moist air from the south, bringing ample snow- or rainfall, and even in summer, winds will tend to blow onshore. The strength and frequency of the rainfall will depend from several factors, including the presence of El Niño (more mild and rainy weather) or La Niña (colder and drier periods due to the presence of an anticyclone in the Gulf of Alaska). Conversely, offshore winds from the interior are normally dry but may have extreme variations in temperature.[21]

Temperatures vary relatively little over the year. Winters are mild by Alaskan standards, with the average temperature of January slightly below freezing and highs often above 32 °F (0.0 °C); summers are rather cool but occasionally may get warm. Temperatures above 75 °F (23.9 °C) or below 10 °F (−12.2 °C) are not unheard of but are rare. Precipitation falls on an average 230 days per year, averaging 62.27 inches (1,580 mm) at the airport (1981–2010 normals), but ranging from 55 to 92 inches (1,400 to 2,340 mm), depending on location.[23] Most of it will occur in fall and winter, some falling as snow from November to March. Both temperatures and precipitation are set to increase in Juneau in the future due to climate change.[21]

Records have been officially kept at downtown Juneau from January 1890 to June 1943, and at Juneau International Airport since July 1943. The coldest temperature ever officially recorded in Juneau was −22 °F (−30.0 °C) on February 2, 1968, and January 12, 1972, while the hottest was 90 °F (32.2 °C) on July 7, 1975.[24] The normals and record temperatures for both downtown and the airport are given below.

| Climate data for Juneau, Alaska (Juneau Int'l, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1936–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 60 (16) |

57 (14) |

61 (16) |

74 (23) |

82 (28) |

86 (30) |

90 (32) |

84 (29) |

78 (26) |

63 (17) |

56 (13) |

54 (12) |

90 (32) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 45.2 (7.3) |

45.7 (7.6) |

49.3 (9.6) |

61.5 (16.4) |

72.1 (22.3) |

78.0 (25.6) |

77.7 (25.4) |

76.5 (24.7) |

66.4 (19.1) |

55.8 (13.2) |

47.5 (8.6) |

45.2 (7.3) |

80.9 (27.2) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 33.1 (0.6) |

35.7 (2.1) |

39.2 (4.0) |

48.7 (9.3) |

57.6 (14.2) |

62.4 (16.9) |

64.0 (17.8) |

62.9 (17.2) |

56.1 (13.4) |

47.3 (8.5) |

38.3 (3.5) |

34.7 (1.5) |

48.3 (9.1) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 28.5 (−1.9) |

30.1 (−1.1) |

32.9 (0.5) |

40.8 (4.9) |

49.0 (9.4) |

54.6 (12.6) |

57.0 (13.9) |

56.0 (13.3) |

50.1 (10.1) |

42.2 (5.7) |

33.8 (1.0) |

30.3 (−0.9) |

42.1 (5.6) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 23.8 (−4.6) |

24.6 (−4.1) |

26.6 (−3.0) |

32.9 (0.5) |

40.3 (4.6) |

46.8 (8.2) |

50.1 (10.1) |

49.1 (9.5) |

44.1 (6.7) |

37.1 (2.8) |

29.2 (−1.6) |

25.9 (−3.4) |

35.9 (2.2) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 6.0 (−14.4) |

9.7 (−12.4) |

12.2 (−11.0) |

22.8 (−5.1) |

31.3 (−0.4) |

38.7 (3.7) |

43.7 (6.5) |

41.4 (5.2) |

32.8 (0.4) |

24.9 (−3.9) |

14.6 (−9.7) |

8.9 (−12.8) |

−0.3 (−17.9) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −22 (−30) |

−22 (−30) |

−15 (−26) |

6 (−14) |

25 (−4) |

31 (−1) |

36 (2) |

27 (−3) |

23 (−5) |

11 (−12) |

−5 (−21) |

−21 (−29) |

−22 (−30) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 6.02 (153) |

4.31 (109) |

3.67 (93) |

3.47 (88) |

3.51 (89) |

3.82 (97) |

5.14 (131) |

6.41 (163) |

9.15 (232) |

8.42 (214) |

6.54 (166) |

6.53 (166) |

66.99 (1,702) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 24.5 (62) |

16.7 (42) |

12.4 (31) |

1.2 (3.0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.9 (2.3) |

13.8 (35) |

18.1 (46) |

87.6 (223) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 20.4 | 16.7 | 17.8 | 17.2 | 16.1 | 16.7 | 18.5 | 19.4 | 22.3 | 23.0 | 20.9 | 21.1 | 230.1 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 10.3 | 8.1 | 7.5 | 1.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.6 | 6.3 | 10.5 | 43.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 79.9 | 80.8 | 79.4 | 76.8 | 76.3 | 78.3 | 81.3 | 84.3 | 87.9 | 87.7 | 85.1 | 82.8 | 81.7 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 18.0 (−7.8) |

22.8 (−5.1) |

26.2 (−3.2) |

31.8 (−0.1) |

38.8 (3.8) |

45.5 (7.5) |

49.5 (9.7) |

49.5 (9.7) |

45.3 (7.4) |

38.5 (3.6) |

28.2 (−2.1) |

22.3 (−5.4) |

34.7 (1.5) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 80.9 | 89.2 | 137.3 | 182.3 | 231.7 | 189.3 | 182.9 | 161.6 | 109.6 | 66.2 | 58.5 | 41.2 | 1,530.7 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 36 | 34 | 37 | 42 | 44 | 35 | 34 | 34 | 28 | 21 | 25 | 20 | 34 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity, dew point, and sun 1961–1990)[24][25][26] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Juneau, Alaska (Downtown, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1890–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 60 (16) |

57 (14) |

61 (16) |

72 (22) |

80 (27) |

87 (31) |

89 (32) |

87 (31) |

85 (29) |

68 (20) |

64 (18) |

59 (15) |

89 (32) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 46.6 (8.1) |

48.2 (9.0) |

49.2 (9.6) |

60.1 (15.6) |

72.4 (22.4) |

78.1 (25.6) |

77.6 (25.3) |

76.4 (24.7) |

67.0 (19.4) |

57.3 (14.1) |

49.6 (9.8) |

47.2 (8.4) |

81.1 (27.3) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 34.1 (1.2) |

36.7 (2.6) |

39.4 (4.1) |

48.6 (9.2) |

57.3 (14.1) |

62.2 (16.8) |

62.9 (17.2) |

62.4 (16.9) |

55.9 (13.3) |

47.9 (8.8) |

39.9 (4.4) |

36.3 (2.4) |

48.6 (9.2) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 30.3 (−0.9) |

32.2 (0.1) |

34.5 (1.4) |

42.2 (5.7) |

50.2 (10.1) |

55.6 (13.1) |

57.3 (14.1) |

56.7 (13.7) |

51.1 (10.6) |

43.7 (6.5) |

36.0 (2.2) |

32.5 (0.3) |

43.5 (6.4) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 26.5 (−3.1) |

27.7 (−2.4) |

29.6 (−1.3) |

35.8 (2.1) |

43.1 (6.2) |

49.0 (9.4) |

51.8 (11.0) |

51.0 (10.6) |

46.3 (7.9) |

39.4 (4.1) |

32.1 (0.1) |

28.7 (−1.8) |

38.4 (3.6) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 10.3 (−12.1) |

15.5 (−9.2) |

17.4 (−8.1) |

28.0 (−2.2) |

35.3 (1.8) |

42.3 (5.7) |

47.0 (8.3) |

45.0 (7.2) |

39.0 (3.9) |

29.8 (−1.2) |

21.2 (−6.0) |

15.7 (−9.1) |

7.2 (−13.8) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −20 (−29) |

−15 (−26) |

−5 (−21) |

12 (−11) |

26 (−3) |

32 (0) |

39 (4) |

32 (0) |

28 (−2) |

13 (−11) |

−7 (−22) |

−10 (−23) |

−20 (−29) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 5.88 (149) |

5.16 (131) |

6.17 (157) |

4.76 (121) |

5.09 (129) |

4.90 (124) |

6.21 (158) |

7.76 (197) |

12.71 (323) |

12.27 (312) |

8.75 (222) |

9.93 (252) |

89.59 (2,276) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 16.9 | 18.8 | 19.6 | 19.3 | 17.8 | 16.9 | 17.0 | 20.3 | 24.0 | 22.6 | 22.5 | 19.4 | 235.1 |

| Source: NOAA[24][27] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Juneau, Alaska (Douglas, 1991–2020 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 8.20 (208) |

5.05 (128) |

5.15 (131) |

5.23 (133) |

4.86 (123) |

5.23 (133) |

7.68 (195) |

8.48 (215) |

11.57 (294) |

10.13 (257) |

8.84 (225) |

8.12 (206) |

88.54 (2,249) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 21.8 | 17.8 | 15.6 | 20.1 | 15.9 | 20.1 | 19.5 | 20.7 | 22.6 | 22.8 | 21.7 | 24.2 | 242.8 |

| Source: NOAA[24] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1890 | 1,253 | — | |

| 1900 | 1,864 | 48.8% | |

| 1910 | 1,644 | −11.8% | |

| 1920 | 3,058 | 86.0% | |

| 1930 | 4,043 | 32.2% | |

| 1940 | 5,729 | 41.7% | |

| 1950 | 5,956 | 4.0% | |

| 1960 | 6,797 | 14.1% | |

| 1970 | 6,050 | −11.0% | |

| 1980 | 19,528 | 222.8% | |

| 1990 | 26,751 | 37.0% | |

| 2000 | 30,711 | 14.8% | |

| 2010 | 31,275 | 1.8% | |

| 2020 | 32,255 | 3.1% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[28] 2020[2] | |||

Juneau first appeared on the 1890 U.S. Census. It formally incorporated in 1900.

As of the 2010 census, there were 31,275 people, 12,187 households, and 7,742 families residing in the city/borough. The population density was 11.3 per square mile (4.4/km2), making it the least densely populated state capital. There were 13,055 housing units at an average density of 4.0 per square mile (1.5/km2). The racial makeup of the city/borough was 69.4% White (67.4% Non-Hispanic White, down from 83.2% in 1980),[29] 0.9% African American, 11.8% Native American or Alaska Native, 6.1% Asian (4.5% Filipino, 0.5% Indian, 0.3% Chinese, 0.3% Korean, 0.2% Japanese, 0.1% Vietnamese), 0.7% Pacific Islander, and 1.2% from other races, and 9.5% from two or more races. 5.1% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.[30] 2.6% reported speaking Tagalog at home, and 2.4% reported speaking Spanish.[31]

There were 11,543 households, out of which 36.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 51.2% were married couples living together, 10.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 33.8% were non-families. 24.4% of all households were made up of individuals, and 4.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.60 and the average family size was 3.10.

The age distribution of Juneau was as follows: 27.4% of the population was under the age of 18, 8.1% were from 18 to 24, 32.8% from 25 to 44, 25.7% from 45 to 64, and 6.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 35 years. For every 100 females, there were 101.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 100.2 males.

The median income for a household in the city/borough was $62,034, and the median income for a family was $70,284. Males had a median income of $46,744 versus $33,168 for females. The per capita income for the city/borough was $26,719. 6.0% of the population and 3.7% of families were below the poverty line, including 6.7% of those under the age of 18 and 3.9% of those 65 and older.

Economy

As the capital of Alaska, the primary employer in Juneau is government. This includes the state government, federal government (which has regional offices here, especially for resource agencies), municipal government (which includes the local airport, hospital, harbors, and school district), and the University of Alaska Southeast. State government offices and their indirect economic impact compose approximately one-quarter of Juneau's economy.[32]

Another large contributor to the local economy is the tourism industry, which generates most income in the summer months. In 2005, the cruise ship industry was estimated to bring nearly one million visitors to Juneau for up to 11 hours at a time, between May and September.[34] While cruise ships provide an economic boost to segments of the economy, not all locals are appreciative. The Juneau Public Library, built atop a parking garage along South Franklin Street near the Red Dog Saloon, was designed to take advantage of the view of and across Gastineau Channel. This view is often blocked by docking cruise ships, which have become so large that they tower over the five-story structure. Bill Ray, who lived in Juneau from 1938 to 2000 and represented the community in the Alaska Legislature from 1965 to 1987, said when he paid a return visit in 2003: "Juneau doesn't go forward. They've prostituted themselves to tourism. It looks like a poor man's Lahaina".[35]

The fishing industry is still a major part of the Juneau economy, while not as strong as when the halibut schooner fleet generated considerable profits. Juneau was recently the 49th most lucrative U.S. fisheries port by volume and 45th by value. In 2004 it took in 15 million pounds of fish and shellfish, valued at 21.5 million dollars, according to the National Marine Fisheries Service. While the port of Juneau does comparatively little seafood processing compared to other towns of this size in Alaska, the hundreds of commercial fishing boats sell their fish to plants in nearby Sitka, Hoonah, Petersburg and Ketchikan. The largest fleets operating from Juneau are the gillnet and troll salmon fleets.

Juneau is also the home to many of the commercial fishing associations in Alaska, as they want to educate and lobby the state legislature. These associations include the Alaska Trollers Association, United Fishermen of Alaska, United Southeast Alaska Gillnetters Association, and the Southeast Alaska Seiners Association.

Real estate agencies, federally funded highway construction, and mining are still viable non-government local industries. Alaska Seaplanes, an airline, has its headquarters in Juneau.[36] Highliner Construction, a general contractor is based there as well.[37] As of Census 2010 there were 1,107 businesses with operations in Juneau borough and thus, with a population of 31,275, a per capita of roughly 28 people per business.

Juneau's only power utility is Alaska Electric Light & Power (AEL&P). Most of the electricity in the borough is generated at the Snettisham Hydroelectric facility in the southern end of the borough, accessible only by boat or plane. In April 2008, an avalanche destroyed three transmission towers, forcing AEL&P to supply almost all of the borough's electricity from diesel-powered generators for one month.[38]

Also headquartered in Juneau is the Marine Exchange of Alaska, a nonprofit organization which operates an extensive vessel tracking network and ensures safe maritime operations for the entire state.[39]

Companies based in Juneau include Sealaska Corporation.

Juneau hosts a major Zip-line attraction developed by Experience Based Learning.

Culture

Juneau hosts the annual Alaska Folk Festival, Juneau Jazz & Classics music festival, and Celebration, a biennial Alaska Native cultural festival.

Juneau has a city-owned ski resort, Eaglecrest, located on Douglas Island.

The city-owned Treadwell ice-skating rink is located on the south end of Douglas Island. It is named after the Treadwell Gold Mine, which is located next to the rink. The rink is open for figure skating, hockey and free open skate. From September to April; when the ice is melted it is used for rollerblading, roller hockey, tennis, basketball, concerts.[40]

The city has a vibrant performing arts scene and is home to Perseverance Theatre, Alaska's largest professional theater, the non-profit Theatre in the Rough, Theater Alaska, Theater at Latitude 58, and Juneau Ghost Light Theatre (formerly Juneau Douglas Little Theatre). The Juneau Symphony performs regularly. The Juneau Lyric Opera and Opera to Go are the two local opera companies. The JUMP Society hosts screenings of locally made short films two times a year. The local art house cinema is Gold Town Nickelodeon which plays independent films, foreign films, classics, and also runs the drive-in.

Downtown Juneau has art galleries that participate in the monthly First Friday Art Walk and annual Gallery Walk held in the first week of December. The Juneau Arts & Humanities Council coordinates events and operates the Juneau Arts & Culture Center, which features a community center, gallery and lobby shop. The University of Alaska Southeast Campus offers lectures, concerts, and theater performances. Sealaska Heritage, the nonprofit affiliate of the Sealaska Corporation, operates The Walter Soboleff Building which is decorated by carvings and hosts cultural exhibits.

Efforts to move state capital

Throughout its statehood, there have been efforts and discussions on moving Alaska's capital away from Juneau.[41] A primary motivating factor has been concerns about Juneau's remote location.[42]

In 1960, 56% of voters voted against a measure to move the capital to a location in the "Cook Inlet-Railbelt Area" (the specific location would subsequently be selected by a committee appointed by the governor).[41] In 1962, 55% of voters voted against a measure to move the capital to "Western Alaska...within 30 miles of Anchorage" which would have seen "senior" state senators select three potential sites to be put to a vote by later vote by the state's electorate.[41]

In 1974, at a time when Alaska was expected to be flush with new funds from the Trans-Alaska Pipeline, 56% Alaskan voters approved an initiative to move the capital.[41][42][43] The initiative specified that the new location must be within 300 miles of both Anchorage and Fairbanks and have at least 100 square miles of donated public land. The initiative would have the final location selected by a committee appointed by the governor. The committee proposed Larson Lake, Mount Yenlo, and Willow as sites, and Willow received 53% of votes in a 1976 statewide vote. However, in 1978, voters rejected a measure to fund a move to Willow, with 55% of voters voting against spending $996 million to move the capital there.[41][42] In 1978, voters also approved the Fiscally Responsible Alaskans Needing Knowledge (FRANK) Initiative, which required that all costs of moving the capital be disclosed and approved by Alaskans before the move commenced.[41] In 1982, 53% of voters voted against spending roughly $2.9 billion to move the capital to Willow. This vote also had the effect of repealing the previous approval of moving the capital.[41]

In 1994, a statewide initiative to move Alaska's capital to Wasilla was defeated by a vote of about 116,000 116,277 (54.7%) to 96,398 (45.3%). At the same time, 77% of voters approved a renewed FRANK Initaitve.[41][44][45]

In 2002, Alaskan voters again voted against moving the state's capital.[42]

Notable people

- Elizabeth Peratrovich (1911–1958), civil rights activist, Grand President of the Alaska Native Sisterhood, member of the Tlingit nation.

- Carlos Boozer (born 1981), professional basketball player

- Gab Cody, playwright, filmmaker

- Dale DeArmond (1914–2006), printmaker

- Neva Egan (1914–2011), Educator and First Lady of Alaska

- Janet Gardner (born 1962), singer of the hard rock band Vixen

- Al Gross (born 1962), surgeon, fisherman, and politician

- Rie Muñoz (1921–2015), artist and Bureau of Indian Affairs educator

- Linda Rosenthal, violinist

- Paul Rosenthal (born 1942), violinist

- Lynn Schooler, photographer, writer who authored The Blue Bear

- James Schoppert (1947–1992), carver, painter

- Molly Smith, theatre director

Government and politics

The City and Borough of Juneau operates under a council–manager form of government. The mayor is the titular head of the city, is the presiding officer (or chair) of the Juneau Assembly (council), and is one of three members of that body elected at-large, or areawide. The remaining six members are elected by single-member districts: two districts have been defined by the Assembly, as of its last redistricting in 2003:[47]

|

|

They hire a professional city manager to handle daily affairs and a city attorney for legal matters.

These districts are nearly aligned with the boundaries of the 31st and 32nd election districts that were established by the state. The main difference is that the 32nd District includes communities outside the CBJ: Gustavus, Kupreanof, Petersburg, Skagway and Tenakee Springs. The Juneau Airport precinct is in the 31st district, which is otherwise identical to the 2nd Assembly District.

Since Juneau was split into two state house districts by the state during redistricting in the early 1990s, the districts comprising downtown Juneau, Douglas Island and surrounding areas have exclusively elected Democrats to the Alaska House of Representatives, while the districts comprising Mendenhall Valley and surrounding areas have mostly elected Republicans. The 31st District is represented in the House by Democrat Andi Story, who has been in office since 2018. The 32nd District is represented by Democrat Sara Hannan.

Combined, these two election districts form Alaska Senate District Q. That seat is held by Democrat Jesse Kiehl. The last Republican to represent Juneau in the state Senate was Elton Engstrom, Jr., the father of Cathy Muñoz. He left office at the end of his term in early 1971, after failing to be re-elected in 1970.

| Year | Democrat | Republican |

|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 64.4% | 32.4% |

| 2004 | 59.2% | 37.3% |

While there are more state jobs based in Anchorage than in Juneau, the state government still maintains a substantial presence in Juneau. A number of executive branch departments, as well as the legislature, are based in Juneau. The legislature, in response to repeated pressure from Southcentral Alaska to move either the capital or the legislature, acquired and renovated several buildings in the vicinity of the Alaska State Capitol, which hold committee meeting rooms and administrative offices for the Legislative Affairs Agency. These buildings were named for former legislators Terry Miller and Thomas B. Stewart. Stewart, a Juneau native and son of early Juneau mayor Benjamin D. Stewart, represented Juneau in the Senate during the 1st Alaska State Legislature. He later served in Juneau's Alaska Superior Court judgeship and was noted as an authority on the latter territory/early statehood eras of Alaska's history.

The federal government has a nine-story federal building in Juneau in the area known as "The Flats". Along Gold Creek near its mouth and a short distance east of the Juneau-Douglas Bridge, the building houses numerous federal agencies, the United States District Court for the District of Alaska, and Juneau's main post office. It was designed by Linn A. Forrest and constructed in 1966. Under the Alaska Statehood Act, the Federal and Territorial Building was transferred to the new state for use as its capitol.

Juneau is one of the most Democratic boroughs in Alaska. The Borough has voted Democratic in the U.S. presidential election in every election (except for one) since 1988.

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third party | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2020 | 6,210 | 35.11% | 10,834 | 61.25% | 643 | 3.64% |

| 2016 | 5,690 | 34.57% | 8,734 | 53.07% | 2,033 | 12.35% |

| 2012 | 6,108 | 37.90% | 9,251 | 57.40% | 757 | 4.70% |

| 2008 | 7,124 | 40.70% | 9,819 | 56.10% | 560 | 3.20% |

| 2004 | 5,515 | 47.20% | 5,784 | 49.50% | 386 | 3.30% |

| 2000 | 7,270 | 45.30% | 6,403 | 39.90% | 2,375 | 14.80% |

| 1996 | 6,004 | 39.30% | 6,768 | 44.30% | 2,506 | 16.40% |

| 1992 | 5,348 | 35.00% | 6,754 | 44.20% | 3,178 | 20.80% |

| 1988 | 5,957 | 48.20% | 6,056 | 49.00% | 345 | 2.79% |

| 1984 | 7,323 | 56.60% | 5,292 | 40.90% | 324 | 2.50% |

| 1980 | 4,600 | 44.80% | 3,594 | 35.00% | 2,075 | 20.21% |

| 1976 | 4,676 | 58.80% | 2,887 | 36.30% | 390 | 4.90% |

| 1972 | 3,678 | 56.00% | 2,725 | 41.49% | 165 | 2.51% |

| 1968 | 2,532 | 44.70% | 2,770 | 48.91% | 362 | 6.39% |

| 1964 | 1,544 | 29.09% | 3,763 | 70.91% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1960 | 2,328 | 52.49% | 2,107 | 47.51% | 0 | 0.00% |

Education

Primary and secondary schools

Juneau is served by the Juneau School District,[50] and includes the following schools:[51]

|

|

The following private schools serve Juneau:

- (Glacier) Valley Baptist Academy

- Faith Community School

- Thunder Mountain Learning Center (Formerly Thunder Mountain Academy)

- Juneau Seventh-day Adventist Christian School

- Juneau Montessori School

Colleges and universities

The University of Alaska Southeast is within the Auke Bay community along the shore of Auke Lake. Juneau-Douglas Community College, founded in 1956, and Southeastern Senior College, established in 1972, were merged in 1980 forming the University of Alaska Juneau. The university was restructured as the University of Alaska Southeast to include Ketchikan and Sitka campuses. The university offers undergraduate and graduate studies. The University of Alaska Fairbanks has a satellite campus in Juneau for marine studies, primarily graduate level.

Transportation

Juneau is not directly accessible by road, although there are road connections within the borough to rural areas. Glacier Highway section of Alaska Route 7 runs within Juneau. Primary access to the city is by air and sea. Cars and trucks are transported to and from Juneau by barge or the Alaska Marine Highway ferry system.

Sea

The state-owned ferry system is called the Alaska Marine Highway. The Southeast ferries connect Juneau with 13 other cities in Southeast Alaska and other destinations north via Whittier, as well as with the continental road system in Bellingham, Washington, and Prince Rupert, British Columbia. Going north, the ferries dock in Haines and Skagway connecting to the Alaska Highway via Whitehorse, Yukon.[56] In addition to the traditional Alaska Marine Highway ferries, high-speed catamarans known as "Fast cats" connect Juneau with Haines and Skagway (91 miles (146 km)) in half the time of the traditional ferries, needing around four hours' travel time.[57]

Air

Juneau International Airport serves the city and borough of Juneau. Alaska Airlines services the airport year round, operating upwards of 11 daily departures. Alaska Airlines serves Juneau and other Southeast Alaska villages via "Milk Run" flights which make multiple stops to and from Seattle or Anchorage. Alaska also connects Juneau to other cities in the country through connections in Seattle or Anchorage.

In the summer, Delta Air Lines serves Juneau from its major West Coast hub in Seattle, providing global service to and from Southeast Alaska without having to switch air carriers.

In the past, MarkAir and Western Airlines serviced Juneau.[58] Alaska Seaplanes and Ward Air offer charter seaplane service from the seaplane floatpond "runway" that runs parallel to the traditional tarmac. They offer service to the smaller villages in the surrounding area as well as flightseeing.

Alaska Seaplanes, Harris Air, and Island Air Express provide FAA Part 135 scheduled commuter service to communities throughout Southeast Alaska. These trips are the only connections to the outside world for many of these villages. Alaska Seaplanes has restored scheduled international service to Juneau with 3 weekly trips to Whitehorse, Canada, while Ward Air provides unscheduled charter flights to Canada.[59]

Roads

Avalanche hazards, steep slopes, cold weather and environmental protection concerns are factors that make road construction and maintenance both difficult and costly.

The Juneau-Douglas Bridge connects the Juneau mainland with Douglas Island.

There are no roads connecting Juneau to the rest of North America, although cars can use the ferries to connect to the road network. Juneau is one of only four state capitals not served by an Interstate highway (the others being Dover, Delaware, Jefferson City, Missouri, and Pierre, South Dakota).[60]

Juneau Access Project

Juneau's roads remain separate from other roads in Alaska and in the Lower 48. There have been plans to connect Juneau to Haines and Skagway by road since before 1972, with funding for the first feasibility study acquired in 1987.[61] The State of Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities announced in 2005 that the connection was to be provided partly by road, and partly by fast ferry. A 51-mile (82 km) road would be built on the east side of Lynn Canal to a new ferry terminal at the Katzehin River estuary.[62] A ferry would take cars from the terminal to Haines and Skagway, where the cars could then access the rest of North America.[62] In 2006, the project was estimated to cost $258 million, and in 2007, the estimate was increased to $350 million.[62] Annual costs have been estimated from $2.1 million to $12 million, depending on the length of the road.[61] The Western Federal Lands Center estimates the project will cost $491 million.[62] As of 2009, $25 million has been spent on the project.[62]

Local opinions on constructing a road link to the outside world are mixed. Some residents see such a road as a much-needed link between Juneau and the rest of the world which will also provide great economic benefits to the city, while many other residents are concerned about the project's financial costs along with environmental and social impacts.[63]

Citing the state's multibillion-dollar financial crisis, Governor Bill Walker announced on December 15, 2016, that the state is no longer backing construction of the Juneau Access Improvements Project.[64]

Public transportation

Local government operates a bus service under the name Capital Transit.

Walking, hiking, and biking

Residents walk, hike, or ride bicycles for recreational purposes and for transportation. The downtown area of Juneau has sidewalks, and the neighborhoods on the hill above downtown are accessible by foot. Some roads in the city also have bike lanes, and there is a bike path parallel to the main highway.

Infrastructure

Healthcare

The city and borough is primarily served by Bartlett Regional Hospital in Juneau's Twin Lakes area. The hospital also serves the nearby remote communities of Hoonah, Haines, and Skagway. Individuals in these communities must be airlifted to the hospital via helicopter or air ambulance (ranging from a 20-minute to a 45-minute flight, depending on location).

Utilities

Juneau is served by the following utilities:

- Electric: Alaska Electric Light and Power Company

- Water and Sewer: City and Borough of Juneau

Media

Print

Juneau's only daily newspaper, the Juneau Empire, is published Sunday through Friday, with no Saturday edition. There is also a regional weekly newspaper, the Capital City Weekly. The University of Alaska Southeast has The Whalesong, a college newspaper.

Radio

- AM: KJNO 630, KINY 800, KXXJ 1330

- FM: KTKU 105.1, KSUP 106.3, and LPFM station KBJZ-LP 94.1.

- Public Radio: KTOO 104.3, KXLL "Excellent Radio" 100.7 and KRNN "Rain Country Radio" 102.7 (all 3 operated by KTOO).

The studios of CoastAlaska (a regional public radio station consortium), are in Juneau. AP (the Associated Press), Anchorage news outlets, and other Alaska media entities, send reporters to Juneau during the annual Legislative session.

Television

Juneau's major television affiliates are: KTOO (PBS), 360 North "Alaska's public affairs channel" (Operated by KTOO), KATH-LD (NBC), and KJUD (ABC)/The CW on DT2. Fox and MyNetworkTV are only available on cable via their Anchorage affiliates.

The Juneau-Douglas High School video program produces television programming, including a weekly 10-minute TV newscast, JDTV News, during the spring semester.

Sister cities

Juneau has five official sister cities.[65]

.svg.png.webp) Whitehorse, Yukon, Canada

Whitehorse, Yukon, Canada.svg.png.webp) Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada

Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada Chiayi City, Taiwan[66]

Chiayi City, Taiwan[66] Vladivostok, Primorsky Krai, Russia

Vladivostok, Primorsky Krai, Russia Kalibo, Aklan, Philippines [67]

Kalibo, Aklan, Philippines [67]

See also

- Juneau gold belt

- Adair-Kennedy Memorial Park

- Capital City Fire/Rescue

- Evergreen Cemetery

- Hurff Ackerman Saunders Federal Building and Robert Boochever U.S. Courthouse

- Juneau Mountain Rescue

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Juneau, Alaska

- Alaska Route 7

- Out the road, a region of Juneau

Notes

- "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- "QuickFacts: Juneau city and borough, Alaska". census.gov. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- Rickard, Thomas Arthur (1909). Through the Yukon and Alaska. Mining and Scientific Press. p. 22.

- States, United (1916). Federal Statutes Annotated: Containing All the Laws of the United States of a General, Permanent and Public Nature in Force on the First Day of January, 1916. Edward Thompson Company. p. 251.

- Miller, Marian (June 9, 1997). "An Outline History of Juneau Municipal Government". City and Borough of Juneau. Archived from the original on July 15, 2006. Retrieved May 3, 2012.

- ICTMN Staff, "Indian Point Goes on National Register of Historic Places" Archived August 21, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Indian Country Today, 18 August 2016; accessed 21 August 2016

- Lisa Phu, "Feds designate Juneau's Indian Point as sacred, worthy of protection" Archived August 20, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Juneau Empire, 16 August 2016; accessed 21 August 2016

- Vancouver, George; Vancouver, John (1801). A voyage of discovery to the North Pacific ocean, and round the world. vols. I-VI. London: J. Stockdale.

- Arthur C. Spencer (1906). The Juneau Gold Belt, Alaska, USGS Bulletin No. 287. United States Government Printing Office. pp. 2–3.

- Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. p. 171. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- Amos Wallace (April 10, 1973). "St. Nicholas Russian Orthodox Church". National Park Service. and accompanying photos from 1961 and 1972

- Jeremy Hsieh (July 13, 2014). "Empty Chair Project recognizes Juneau's Japanese WWII internees". KTOO. Archived from the original on July 9, 2019. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- "Sean Parnell, 10th Governor of Alaska". Gov.state.ak.us. Archived from the original on February 25, 2008. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- "CensusScope − Population Growth". Archived from the original on November 26, 2005. Retrieved November 15, 2005.

- "Juneau's future demographic: Growing older". JuneauAlaska.com. Archived from the original on November 24, 2005. Retrieved November 15, 2005.

- Juneau Named 'Playful' City, Only Honoree in Alaska. Archived August 11, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Juneau Empire, September 3, 2010. Retrieved 2010-11-15.

- "No joke: Alaska city temporarily renamed for card game UNO". Associated Press/CBS News. April 1, 2016. Archived from the original on April 14, 2016. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- "Greetings from 'Uno, Alaska.' Capital city teams up with Mattel for April Fools' Day". KTUU-TV/Gray Television. April 1, 2016. Archived from the original on April 2, 2016. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- Jeneau Trails System Archived May 25, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Alaska Department of Natural Resources

- "Climate change: predicted impacts on Juneau" (PDF). City and Borough of Juneau. April 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

- Shulski, Martha; Wendler, Gerd (2007). The Climate of Alaska. University of Alaska Press. pp. 11, 37–39. ISBN 978-1-60223-007-1.

- "Tongass National Forest – Home". fs.fed.us.

- "NOWData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- "Station Name: AK JUNEAU INTL AP". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- "WMO Climate Normals for Juneau, AK 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- "Station Name: AK JUNEAU DWTN". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "Alaska - Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- "U.S. Census website". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved May 23, 2014.

- "Language Map Data Center".

- The Associated Press. "Alaska capital move would devastate Juneau economy" Archived 2009-04-23 at the Wayback Machine, Fairbanks Daily News-Miner, 19 April 2009; accessed August 2, 2009.

- "WEIDNER APARTMENT HOMES: Mendenhall Tower Apartment Homes". weidner.com. Weidner Apartment Homes. Retrieved September 16, 2019.

- "Cruise outlook for 2005 shows growth". Archived from the original on April 16, 2005. Retrieved November 15, 2005.

- "Memoirs of a longtime lawmaker – Bill Ray comes to Juneau to sign his new book, 'Liquor, Legislation & Laughter'" (PDF). Juneau Empire. Fairbanks: (as hosted by the University of Alaska System). April 25, 2003. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 6, 2012. Retrieved October 24, 2011.

- "Contact Us Archived August 13, 2017, at the Wayback Machine." Alaska Seaplanes. Retrieved on August 12, 2017.

- "Home Page - Highliner Construction". Highlinerak.com. Retrieved March 3, 2022.

- "Snettisham Hydroelectric Project outage causes city to run partly on diesel". Archived from the original on October 7, 2016. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- "Marine Exchange of Alaska – MXAK Overview and Programs". Mxak.org. Archived from the original on November 21, 2015. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- "Ice Arena Juneau's First Public Access Sports Facility in 30 Years". February 23, 2003. Archived from the original on October 14, 2019.

- "The long-debated capital move has resurfaced". Juneau Empire. May 3, 2018. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- Kelly, Casey (March 7, 2013). "Alaska's Capital City Changes With The Times". Alaska Public Media. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- "Alaskans Vote to Move Capital Inland". The New York Times. August 29, 1974. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- Hernandez, Raymond; Hershey, Robert D. Jr.; Holloway, Lynette; Kennedy, Randy; Labaton, Stephen; Lewin, Tamar; Lewis, Neil A.; Onishi, Norimitsu; Schmitt, Eric; Bradsher, Keith (November 10, 1994). "The 1994 Elections: State by State; West". The New York Times. Retrieved September 9, 2008.

- "Alaska's 1994 General Election Results Summary". Alaska Division of Elections. Archived from the original on August 1, 2008. Retrieved September 9, 2008.

- Manning, Phillip; Talkeetna, KTNA- (February 11, 2022). "State Reps. Kurka and Eastman sponsor bill to move the capital from Juneau to Willow". Alaska Public Media. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- "CBJ Assembly Districts" (PDF). juneau.org. Office of the City and Borough of Juneau Clerk. June 30, 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 31, 2013. Retrieved April 12, 2013.

- "2008 Presidential Election Results by House District in Alaska". USA Election Atlas http://uselectionatlas.org/FORUM/index.php?topic=88046.0. Retrieved 5 July 2010

- Elections, RRH (February 2, 2018). "RRH Elections". rrhelections.com. Retrieved January 12, 2020.

- "2020 CENSUS - SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP: Juneau City and Borough, AK" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved July 22, 2022. - Text list

- "Schools in the Juneau School District". Archived from the original on November 11, 2007. Retrieved December 2, 2007.

- Baxter, Adelyn (October 18, 2017). "Same building, new name: Sayéik Gastineau Community School". Alaska Public Media. KTOO FM. Retrieved May 1, 2021.

- "New principal named at Juneau Community Charter School". KINY. Retrieved May 1, 2021.

- Hohenstatt, Ben (May 22, 2019). "'These are the ones to cheer': Ceremony recognizes students as future of Tlingit language, culture". Juneau Empire.

- Barnes, Mollie (January 9, 2019). "Juneau-Douglas changed its name. Here's what it is". Juneau Empire. Retrieved May 1, 2021.

- Alaska Marine Highway System (2008). Alaska Marine Highway System; Annual Traffic Volume Report (PDF) (Report). Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 30, 2013.

- "Vessel Information Table" (PDF). State of Alaska DOT. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 30, 2017. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- Phu, Lisa (April 11, 2016). "Delta to end year-round service in Juneau". JuneauEmprie.com. Juneau Empire. Archived from the original on August 23, 2017. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- "Ward Air". Archived from the original on September 1, 2019. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- "The Dwight D. Eisenhower System of Interstate and Defense Highways - Part VII - Miscellaneous Interstate Facts". Federal Highway Administration. Archived from the original on July 16, 2018. Retrieved June 3, 2018.

- Kleeschulte, Chuck (June 8, 1987). "Haines-to-Juneau road to be studied". Juneau Empire. Juneau, United States.

- Connelly, Joel (July 10, 2009). "Tab for Alaska road: $445 million". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Archived from the original on July 15, 2009. Retrieved July 14, 2009.

- Juneau's Road to Ruin Archived July 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Sierra Club Alaska Chapter.

- "Gov. Walker abandons Juneau access road 15 December 2016". Alaska public media. December 16, 2016. Archived from the original on February 3, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- "The City and Borough of Juneau Homepage". juneau.org. Archived from the original on May 4, 2007. Retrieved November 17, 2007.

- "Sister Partnerships by US State". Asia Matters for America. Retrieved March 3, 2022.

- "Sister Cities Committee". City and Borough of Juneau. Retrieved March 3, 2022.

References

- Andrews, Clarence Leroy (1944). The Story of Alaska. Caldwell, Id: The Caxton Printers, Ltd. OCLC 5024244.

- Naske, Claus-M; Slotnick, Herman E (1987). Alaska: A History of the 49th State. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2099-1.

External links

![]() Media related to Juneau, Alaska at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Juneau, Alaska at Wikimedia Commons