Spirit possession

Spirit possession is an unusual or altered state of consciousness and associated behaviors purportedly caused by the control of a human body by spirits, ghosts, demons, or gods.[1] The concept of spirit possession exists in many cultures and religions, including Buddhism, Christianity,[2] Haitian Vodou, Hinduism, Islam, Wicca, and Southeast Asian, African, and Native American traditions. Depending on the cultural context in which it is found, possession may be considered voluntary or involuntary and may be considered to have beneficial or detrimental effects on the host.[3]

| Part of a series on the |

| Paranormal |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Anthropology of religion |

|---|

|

| Social and cultural anthropology |

In a 1969 study funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, spirit possession beliefs were found to exist in 74% of a sample of 488 societies in all parts of the world, with the highest numbers of believing societies in Pacific cultures and the lowest incidence among Native Americans of both North and South America.[1][4] As Pentecostal and Charismatic Christian churches move into both African and Oceanic areas, a merger of belief can take place, with "demons" becoming representative of the "old" indigenous religions, which the Christian ministers attempt to exorcise.[5]

Abrahamic traditions

Christianity

From its beginning, Christianity has held that possession derives from the Devil, i.e. Satan, his lesser demons, the fallen angels.[6] In the battle between Satan and Heaven, Satan is believed to engage in "spiritual attacks", including demonic possession, against human beings by the use of supernatural powers to harm them physically or psychologically.[1] Prayer for deliverance, blessings upon the man or woman's house or body, sacraments, and exorcisms are generally used to drive the demon out.

Some theologians, such as Ángel Manuel Rodríguez, say that mediums, like the ones mentioned in Leviticus 20:27, were possessed by demons. Another possible case of demonic possession in the Old Testament includes the false prophets that King Ahab relied upon before re-capturing Ramoth-Gilead in 1 Kings 22. They were described to be empowered by a deceiving spirit.[7]

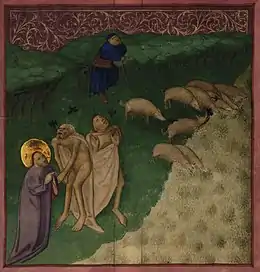

The New Testament mentions several episodes in which Jesus drove out demons from persons.[6] Whilst most Christians believe that demonic possession is an involuntary affliction,[8] some biblical verses have been interpreted as indicating that possession can be voluntary. For example, Alfred Plummer writes that when Satan entered into Judas Iscariot in John 13:27, this was because Judas had continually agreed to Satan's suggestions to betray Jesus and had wholly submitted to him.[9]

The New Testament indicates that people can be possessed by demons, but that the demons respond and submit to Jesus Christ's authority:

In the synagogue, there was a man possessed by a demon, an evil spirit. He cried out at the top of his voice, "Ha! What do you want with us, Jesus of Nazareth? Have you come to destroy us? I know who you are—the Holy One of God!" "Be quiet!" Jesus said sternly. "Come out of him!" Then the demon threw the man down before them all and came out without injuring him. All the people were amazed and said to each other, "What is this teaching? With authority and power he gives orders to evil spirits and they come out!" And the news about him spread throughout the surrounding area

— Luke 4:33-35[10]

It also indicates that demons can possess animals as in the exorcism of the Gerasene demoniac.

Catholicism

Roman Catholic doctrine states that angels are non-corporeal, spiritual beings[11] with intelligence and will.[12] Fallen angels, or demons, are able to "demonically possess" individuals without the victim's knowledge or consent, leaving them morally blameless.[13]

The Catholic Encyclopedia says that there is only one apparent case of demonic possession in the Old Testament, of King Saul being tormented by an "evil spirit" (1 Samuel 16:14), but this depends on interpreting the Hebrew word "rûah" as implying a personal influence which it may not, so even this example is described as "not very certain". In addition, Saul was only described to be tormented, rather than possessed, and he was relieved from these torments by having David play the lyre to him.[14]

Catholic exorcists differentiate between "ordinary" Satanic/demonic activity or influence (mundane everyday temptations) and "extraordinary" Satanic/demonic activity, which can take six different forms, ranging from complete control by Satan or demons to voluntary submission:[13]

- Possession, in which Satan or demons take full possession of a person's body without their consent. This possession usually comes as a result of a person's actions; actions that lead to an increased susceptibility to Satan's influence.

- Obsession, which includes sudden attacks of irrationally obsessive thoughts, usually culminating in suicidal ideation, and which typically influences dreams.

- Oppression, in which there is no loss of consciousness or involuntary action, such as in the biblical Book of Job in which Job was tormented by Satan through a series of misfortunes in business, material possessions, family, and health.

- External physical pain caused by Satan or demons.

- Infestation, which affects houses, objects/things, or animals; and

- Subjection, in which a person voluntarily submits to Satan or demons.

In the Roman Ritual, true demonic or Satanic possession has been characterized since the Middle Ages, by the following four typical characteristics:[15][16]

- Manifestation of superhuman strength.

- Speaking in tongues or languages that the victim cannot know.

- Revelation of knowledge, distant or hidden, that the victim cannot know.

- Blasphemous rage, obscene hand gestures, using profanity and an aversion to holy symbols, names, relics or places.

The New Catholic Encyclopedia states, "Ecclesiastical authorities are reluctant to admit diabolical possession in most cases, because many can be explained by physical or mental illness alone. Therefore, medical and psychological examinations are necessary before the performance of major exorcism. The standard that must be met is that of moral certitude (De exorcismis, 16). For an exorcist to be morally certain, or beyond reasonable doubt, that he is dealing with a genuine case of demonic possession, there must be no other reasonable explanation for the phenomena in question".[17]

Official Catholic doctrine affirms that demonic possession can occur as distinguished from mental illness,[18] but stresses that cases of mental illness should not be misdiagnosed as demonic influence. Catholic exorcisms can occur only under the authority of a bishop and in accordance with strict rules; a simple exorcism also occurs during baptism.[1]

Reformed

The infliction of demonic torment upon an individual has been chronicled in premodern Protestant literature. In 1597, King James discussed four methods of daemonic influence upon an individual in his book Daemonologie:[19]

- Spectra, being the haunting and troubling of certain houses or solitary places.

- Obsession, the following and outwardly torment of an individual at diverse hours to either weaken or cast diseases upon the body, as in the Book of Job.

- Possession, the entrance inwardly into an individual to beget uncontrollable fits, induce blasphemies,

- Faerie, being the influence those who voluntarily submit to consort, prophesy, or servitude.

King James attested that the symptoms derived from demonic possession could be discernible from natural diseases. He rejected the symptoms and signs prescribed by the Catholic church as vain (e.g. rage begotten from Holy Water, fear of the Cross, etc.) and found that the exorcism rites to be troublesome and ineffective to recite. The Rites of the Catholic Church to remedy the torment of demonic spirits were rejected as counterfeit since few possessed could be cured by them. James therefore declared the Protestant view of casting out devils, "It is easy then to understand that the casting out of Devils, is by virtue of fasting and prayer, and in-calling of the name of God, suppose many imperfections be in the person that is the instrument, as CHRIST himself teaches us (Mat. 7) of the power that false Prophets all have cast out devils".[20]

In medieval Great Britain, the Christian church had offered suggestions on safeguarding one's home. Suggestions ranged from dousing a household with holy water, placing wax and herbs on thresholds to "ward off witches occult," and avoiding certain areas of townships known to be frequented by witches and Devil worshippers after dark.[21] Afflicted persons were restricted from entering the church, but might share the shelter of the porch with lepers and persons of offensive life. After the prayers, if quiet, they might come in to receive the bishop's blessing and listen to the sermon. They were fed daily and prayed over by the exorcists, and, in case of recovery, after a fast of from 20 to 40 days, were admitted to the Eucharist, and their names and cures entered in the church records.[22] In 1603, the Church of England forbade its clergy from performing exorcisms because of numerous fraudulent cases of demonic possession.[18]

Baptist

In May 2021, the Baptist Deliverance Study Group of the Baptist Union of Great Britain, a Christian denomination, issued a "warning against occult spirituality following the rise in people trying to communicate with the dead". The commission reported that "becoming involved in activities such as Spiritualism can open up a doorway to great spiritual oppression which requires a Christian rite to set that person free".[23]

Evangelical

In both charismatic and evangelical Christianity, exorcisms of demons are often carried out by individuals or groups belong to the deliverance ministries movement.[24] According to these groups, symptoms of such possessions can include chronic fatigue syndrome, homosexuality, addiction to pornography, and alcoholism.[25] The New Testament's description of people who had evil spirits includes a knowledge of future events (Acts 16:16) and great strength (Act 19:13-16),[6] among others, and shows that those with evil spirits can speak of Christ (Mark 3:7-11).[6] Some Evangelical denominations believe that demonic possession is not possible if one has already professed their faith in Christ, because the Holy Spirit already occupies the body and a demon cannot enter.

Islam

Various types of creatures, such as jinn, shayatin, ʻafarit, found within Islamic culture, are often held to be responsible for spirit possession. Spirit possession appears in both Islamic theology and wider cultural tradition.

Although opposed by some Muslim scholars, sleeping near a graveyard or a tomb is believed to enable contact with the ghosts of the dead, who visit the sleeper in dreams and provide hidden knowledge.[26] Possession by ʻafarit (a vengeful ghost) are said to grant the possessed some supernatural powers, but it drives them insane as well.[27]

Jinn are much more physical than spirits,[28] however, due to their subtle bodies, which are composed of fire and air (marijin min nar), they are purported to be able to possess the bodies of humans. Such physical intrusion of the jinn is conceptually different from the whisperings of the devils.[29] Though not directly attested in the Quran, the notion of jinn possessing humans is widespread among Muslims and also accepted by most Islamic scholars.[30] Since such jinn are said to have free will, they can have their own reasons to possess humans and are not necessarily harmful. There are various reasons given as to why a jinn might seek to possess an individual, such as falling in love with them, taking revenge for hurting them or their relatives, or other undefined reasons.[31][32] At an intended possession, the covenant with the jinn must be renewed.[33] Since jinn are not necessarily evil, they are distinguished from cultural concepts of possession by devils/demons.[34] It has been argued that the concept of jinn-possession is alien to the Quran and derives from pagan notion of jinn.[35]

In contrast to Jinn, the shayatin are inherently evil.[36] Iblis, the leader of the shayatin, only tempts humans into sin by following their lower nafs.[37][38] Hadiths suggest that the demons/devils whisper from within the human body, within or next to the heart, and so "devilish whisperings" (Arabic: waswās وَسْوَاس) are sometimes thought of as a kind of possession.[39] Unlike possession by jinn, the whisperings of demons affects the soul instead of the body.

Judaism

Although forbidden in the Hebrew Bible, magic was widely practiced in the late Second Temple Period and well documented in the period following the destruction of the Temple into the 3rd, 4th, and 5th centuries C.E.[40][41] Jewish magical papyri were inscriptions on amulets, ostraca and incantation bowls used in Jewish magical practices against shedim and other unclean spirits. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, Jewish methods of exorcism were described in the Book of Tobias.[42][43]

In the 16th century, Isaac Luria, a Jewish mystic, wrote about the transmigration of souls seeking perfection. His disciples took his idea a step further, creating the idea of a dybbuk, a soul inhabiting a victim until it had accomplished its task or atoned for its sin.[44] The dybbuk appears in Jewish folklore and literature, as well as in chronicles of Jewish life.[45] In Jewish folklore, a dybbuk is a disembodied spirit that wanders restlessly until it inhabits the body of a living person. The Baal Shem could expel a harmful dybbuk through exorcism.[46]

Witchcraft

In many practices of witchcraft spirit possession is a very important topic to be discussed. Witchcraft as a whole works with energies and spirits that are in one's surrounding environment. Yet when things may backfire (which happens quite often in witchcraft in spells, rituals etc.). a case of spirit possession isn't uncommon. The way that witches look at spirit possession is exactly as described; a person's body is taken over by an entity, energy, demon or spirit and the human's personality then changes and may be drawn to do certain things they wouldn't have done without this negative energy. For witches, a cleansing or banishment spell is the way to go when dealing with unwanted spirit possession.

Alternatively within witchcraft, spirit possession can be the desired outcome. Invoking spirits in time of great need to lend strength or other characteristics to a given situation.

African traditions

Central Africa

Democratic Republic of the Congo

Zebola[47] is a women's spirit possession dance ritual practised by certain ethnic groups of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It is believed to have therapeutic qualities and has been noted in the West as a traditional form of psychotherapy.

It originated among the Mongo people but is also practised among various ethnic groups in Kinshasa.[48]

Ethiopia

Among the Gurage people of Ethiopia, spirit possession is a common belief. Wiliam A. Shack postulated that it is caused by Gurage cultural attitudes about food and hunger, while they have a plentiful food supply, cultural pressures that force the Gurage to either share it to meet social obligations, or hoard it and eat it secretly cause feelings of anxiety. Distinctions are drawn between spirits that strictly possess men, spirits that possess women, and spirits that possess victims of either sex. A ritual illness that only affects men is believed to be caused by a spirit called awre. This affliction presents itself by loss of appetite, nausea, and attacks from severe stomach pains. If it persists, the victim may enter a trance-like stupor, in which he sometimes regains consciousness long enough to take food and water. Breathing is often labored. Seizures and trembling overcome the patient, and in extreme cases, partial paralysis of the extremities.[49]

If the victim does not recover naturally, a traditional healer, or sagwara, is summoned. Once the sagwara has determined the spirit's name through the use of divination, he prescribes a routine formula to exorcise the spirit. This is not a permanent cure, however, it is believed to allow the victim to form a relationship with the spirit. Nevertheless, the victim is subject to chronic repossession, which is treated by repeating the formula. This formula involves the preparation and consumption of a dish of ensete, butter, and red pepper. During this ritual, the victim's head is covered with a drape, and he eats the ensete ravenously while other ritual participants participate by chanting. The ritual ends when the possessing spirit announces that it is satisfied. Shack notes that the victims are overwhelmingly poor men, and that women are not as food-deprived as men, due to ritual activities that involve food redistribution and consumption. Shack postulates that the awre serves to bring the possessed man to the center of social attention, and to relieve his anxieties over his inability to gain prestige from redistributing food, which is the primary way in which Gurage men gain status in their society.[49]

The belief in spirit possession is part of the native culture of the Sidama people of southwest Ethiopia. Anthropologists Irene and John Hamer postulated that it is a form of compensation for being deprived within Sidama society, although they do not draw from I.M. Lewis (see Cultural anthropology section under Scientific views). The majority of the possessed are women whose spirits demand luxury goods to alleviate their condition, but men can be possessed as well. Possessed individuals of both sexes can become healers due to their condition. Hamer and Hamer suggest that this is a form of compensation among deprived men in the deeply competitive society of the Sidama, for if a man cannot gain prestige as an orator, warrior, or farmer, he may still gain prestige as a spirit healer. Women are sometimes accused of faking possession, but men never are.[50]

East Africa

Kenya

- The Digo people of Kenya refer to the spirits that supposedly possess them as shaitani. These shaitani typically demand luxury items to make the patient well again. Despite the fact that men sometimes accuse women of faking the possessions in order to get luxury items, attention, and sympathy, they do generally regard spirit possession as a genuine condition and view victims of it as being ill through no fault of their own. However, men sometimes suspect women of actively colluding with spirits in order to be possessed.[51]

- The Giriama people of coastal Kenya believe in spirit possession.[52]

Mayote

- In Mayotte, approximately 25% of the adult population, and five times as many women as men, enter trance states in which they are supposedly possessed by certain identifiable spirits who maintain stable and coherent identities from one possession to the next.[53]

Mozambique

- In Mozambique, a new belief in spirit possession appeared after the Mozambican Civil War. These spirits, called gamba, are said to be identified as dead soldiers, and allegedly overwhelmingly possess women. Prior to the war, spirit possession was limited to certain families and was less common.[54]

Uganda

- In Uganda, a woman named Alice Auma was reportedly possessed by the spirit of a male Italian soldier named Lakwena ('messenger'). She ultimately led a failed insurrection against governmental forces.[55]

Tanzania

- The Sukuma people of Tanzania believe in spirit possession.[56]

- A now-extinct spirit possession cult existed among the Hadimu women of Zanzibar, revering a spirit called kitimiri. This cult was described in an 1869 account by a French missionary. The cult faded by the 1920s and was virtually unknown by the 1960s.[57]

Southern Africa

- A belief in spirit possession appears among the Xesibe, a Xhosa-speaking people from Transkei, South Africa. The majority of the supposedly possessed are married women. The condition of spirit possession among them is called inwatso. Those who develop the condition of inwatso are regarded as having a special calling to divine the future. They are first treated with sympathy, and then with respect as they allegedly develop their abilities to foretell the future.[58]

West Africa

- One religion among Hausa people of West Africa is that of Hausa animism, in which belief in spirit possession is prevalent.

African diasporic traditions

In many of the African diaspora religions possessing spirits are not necessarily harmful or evil, but are rather seeking to rebuke misconduct in the living.[59] Possession by a spirit in the African diaspora and traditional African religions can result in healing for the person possessed and information gained from possession as the spirit provides knowledge to the one they possessed.[60][61][62]

Haitian Vodou

In Haitian Vodou and related African diaspora religions, one way that those who participate or practice can have a spiritual experience is by being possessed by the Loa (or lwa). When the Loa descends upon a practitioner, the practitioner's body is being used by the spirit, according to the tradition. Some spirits are believed to be able to give prophecies of upcoming events or situations pertaining to the possessed one, also called a Chwal or the "Horse of the Spirit." Practitioners describe this as a beautiful but very tiring experience. Most people who are possessed by the spirit describe the onset as a feeling of blackness or energy flowing through their body.[63]

Umbanda

The concept of spirit possession is also found in Umbanda, an Afro-Brazilian folk religion. According to tradition, one such possessing spirit is Pomba Gira, who possesses both women and males.[64]

Hoodoo

The culture of Hoodoo was created by African-Americans. There are regional styles to this tradition, and as African-Americans traveled, the tradition of Hoodoo changed according to African-Americans' environment. Hoodoo includes reverence to ancestral spirits, African-American quilt making, herbal healing, Bakongo and Igbo burial practices, Holy Ghost shouting, praise houses, snake reverence, African-American churches, spirit possession, some Nkisi practices, Black Spiritual churches, Black theology, the ring shout, the Kongo cosmogram, Simbi water spirits, graveyard conjuring, the crossroads spirit, making conjure canes, incorporating animal parts, pouring of libations, Bible conjuring, and conjuring in the African-American tradition. In Hoodoo, people become possessed by the Holy Ghost. Spirit possession in Hoodoo was influenced by West African Vodun spirit possession. As Africans were enslaved in the United States, the Holy Spirit (Holy Ghost) replaced the African gods during possession. "Spirit possession was reinterpreted in Christian terms."[60][65] In African-American churches this is called filled with the Holy Ghost. Church members in Black Spiritual churches become possessed by spirits of deceased family members, the Holy Spirit, Christian saints, and other biblical figures from the Old and New Testament of the Bible. It is believed when people become possessed by these spirits they gain knowledge and wisdom and act as intercessors between people and God.[66] William Edward Burghardt Du Bois (W. E. B. Du Bois) studied African-American churches in the early twentieth century. Du Bois asserts that the early years of the Black church during slavery on plantations was influenced by Voodooism.[67][68]

.jpg.webp)

Through counterclockwise circle dancing, ring shouters built up spiritual energy that resulted in the communication with ancestral spirits, and led to spirit possession. Enslaved African Americans performed the counterclockwise circle dance until someone was pulled into the center of the ring by the spiritual vortex at the center. The spiritual vortex at the center of the ring shout was a sacred spiritual realm. The center of the ring shout is where the ancestors and the Holy Spirit reside at the center.[69][70][71] The Ring Shout (a sacred dance in Hoodoo) in Black churches results in spirit possession. The Ring Shout is a counterclockwise circle dance with singing and clapping that results in possession by the Holy Spirit. It is believed when people become possessed by the Holy Spirit their hearts become filled with the Holy Ghost which purifies their heart and soul from evil and replace it with joy.[72] The Ring Shout in Hoodoo was influenced by the Kongo cosmogram a sacred symbol of the Bantu-Kongo people in Central Africa. It symbolizes the cyclical nature of life of birth, life, death, and rebirth (reincarnation of the soul). The Kongo cosmogram also symbolizes the rising and setting of the sun, the sun rising in the east and setting in the west that is counterclockwise, which is why ring shouters dance in a circle counterclockwise to invoke the spirit.[73][74]

Asian traditions

Buddhism

According to the Indian medical literature and Tantric Buddhist scriptures, most of the "seizers", or those that threaten the lives of young children, appear in animal form: cow, lion, fox, monkey, horse, dog, pig, cat, crow, pheasant, owl, and snake. However, apart from these "nightmare shapes", it is believed the impersonation or incarnation of animals could in some circumstances also be highly beneficial, according to Michel Strickmann.[75]

Ch'i Chung-fu, a Chinese gynecologist writing early in the 13th century, wrote that in addition to five sorts of falling frenzy classified according to their causative factors, there were also four types of other frenzies distinguished by the sounds and movements given off by the victim during his seizure: cow, horse, pig, and dog frenzies.[75]

In Buddhism, a māra, sometimes translated as "demon", can either be a being suffering in the hell realm[76] or a delusion.[77] Before Siddhartha became Gautama Buddha, He was challenged by Mara, the embodiment of temptation, and overcame it.[78] In traditional Buddhism, four forms of māra are enumerated:[79]

- Kleśa-māra, or māra as the embodiment of all unskillful emotions, such as greed, hate, and delusion.

- Mṛtyu-māra, or māra as death.

- Skandha-māra, or māra as metaphor for the entirety of conditioned existence.

- Devaputra-māra, the deva of the sensuous realm, who tries to prevent Gautama Buddha from attaining liberation from the cycle of rebirth on the night of the Buddha's enlightenment.[80]

It is believed that a māra will depart to a different realm once it is appeased.[76]

East Asia

Certain sects of Taoism, Korean shamanism, Shinto, some Japanese new religious movements, and other East Asian religions feature the idea of spirit possession. Some sects feature shamans who supposedly become possessed; mediums who allegedly channel beings' supernatural power; or enchanters are said to imbue or foster spirits within objects, like samurai swords.[81] The Hong Kong film Super Normal II (大迷信, 1993) shows the true famous story of a young lady in Taiwan who possesses the dead body of a married woman to live her pre-determined remaining life.[82] She is still serving in the Zhen Tian Temple in Yunlin County.[83]

Background

China is a country where 73.56% of the population is defined as Chinese folk religion/unaffiliated (nonreligion). Therefore, the Chinese population's knowledge of spirit possession is not majorly obtained from religion. Instead, the concept is spread through fairy tales/folk tales and literary works of its traditional culture. In essence, the concept of soul possession has penetrated into all aspects of Chinese life, from people's superstitions, folk taboos, and funeral rituals, to various ghost-themed literary works, and has continued to spread to people's lives today.

Spirit possession and its development

Spirit possession in China was prominent until the Communist takeover in the 1950s and most of the data gathered on this topic will be from the late 18th century. The Chinese believe that illnesses to man is due to the possession of an evil spirit yin spirit (kuei). These evil spirits become such when the deceased are not worshiped by the family, they have died unexpectedly, or did not follow Confucius's ideals of filial piety and ancestral reverence accordingly. These evil spirits cause unexplainable disasters, agricultural shocks and possessions. The Chinese believe that disease is the cause of the supernatural where they do not have control over. Usually in the writings about this, the healers are the ones being described with detail, not so much the patient. Magical practices is sometimes what spirit possession is referred to as. It is very hard to distinguish between the religion, magic and local traditions. This is because many times, all three are fused together, so sometimes trying to distinguish between them is hard.

Shaman

Another type of spirit possession is called the "shaman." It is someone who is a prophet, healer and religious figure all combined. They also have the power to control spirits and serve as a vehicle of communication for them. However, they cannot completely control the spirits. Messages, remedies and even oracles are delivered through the shaman. This has also been used by people who would like to become important figures. Usually shaman gives guidance that already reflect the values of the individuals that are seeking help.[84]

The Yin-yang theory and spirit possession

The yin-yang theory is one of the most important bases and components of Chinese traditional culture. The yin-yang theory has penetrated into various traditional Chinese cultural things including calendar, astronomy, meteorology, Chinese medicine, martial arts, calligraphy, architecture, religion, feng shui, divination, etc. The yin-yang theory also applies to spirit possession. In general, one is considered to be "weak", when the yin and yang in the body are imbalanced, especially when the yin is on the dominant side. The spirits, which are categorized as the yin side, will then take control of these individuals with the imbalanced and yin-dominant situation more easily.

- Shi (Chinese ancestor veneration)

- Shamanism of the Solon People (Inner Mongolia)

- Tangki

Japan

- Misaki

South Asia

Ayurveda

- Bhūtavidyā, the exorcism of possessing spirits, is traditionally one of the eight limbs of Ayurveda.

Rajasthan

- The concept of spirit possession exists in the culture of modern Rajasthan. Some of the spirits allegedly possessing Rajasthanis are seen as good and beneficial, while others are seen as malevolent. The good spirits are said to include murdered royalty, the underworld god Bhaironji, and Muslim saints & fakirs. Bad spirits are believed to include perpetual debtors who die in debt, stillborn infants, deceased widows, and foreign tourists. The supposedly possessed individual is referred to as a ghorala, or "mount". Possession, even if by a benign spirit, is regarded as undesirable, as it is seen to entail loss of self-control, and violent emotional outbursts.[85]

Tamil Nadu

Sri Lanka

- The Coast Veddas, a social group within the minority group of Sri Lankan Tamil people in Eastern Province, Sri Lanka, enter trances during religious festivals in which they are regarded as being possessed by a spirit. Although they speak a dialect of Tamil, during trances they will sometimes use a mixed language that contains words from the Vedda language.[87]

Southeast Asia

Indonesia

In Bali, the animist traditions of the island include a practice called sanghyang, induction of voluntary possession trance states for specific purposes. Roughly similar to voluntary possession in Vaudon (Voodoo), sanghyang is considered a sacred state in which hyangs (deities) or helpful spirits temporarily inhabit the bodies of participants. The purpose of sanghyang is believed to be to cleanse people and places of evil influences and restore spiritual balance. Thus, it is often referred to as an exorcism ceremony. In Sulawesi, the women of the Bonerate people of Sulawesi practice a possession-trance ritual in which they smother glowing embers with their bare feet at the climax. The fact that they are not burned in the process is considered proof of the authenticity of the possession.[88]

Influenced by the religion of Islam, among the several spirits in Indonesian belief are demons (setan), composed of fire, prone to anger and passion. They envy humans for their physical body, and try to gain control of it. When they assault a human, they would intrude their mind, trying to displace the human spirit. The human's mind would adapt to the passions of anger, violence, irrationality and greed, the intruding demon is composed of. The demon is believed to alter the person, giving him supernatural attributes, like strength of many men, ability to appear in more than one place, or assume the form of an animal, such as a tiger or a pig, or to kill without touching. Others become lunatics, resembling epilepsy. In extreme cases, the presence of the demon may alter the condition of the body, matching its own spiritual qualities, turning into a raksasha.[89]

Malaysia

Female workers in Malaysian factories have allegedly become possessed by spirits, and factory owners generally regard it as mass hysteria and an intrusion of irrational and archaic beliefs into a modern setting.[90] Anthropologist Aihwa Ong noted that spirit possession beliefs in Malaysia were typically held by older, married women, whereas the female factory workers are typically young and unmarried. She connects this to the rapid industrialization and modernization of Malaysia. Ong argued that spirit possession is a traditional way of rebelling against authority without punishment, and suggests that it is a means of protesting the untenable working conditions and sexual harassment that the women were compelled to endure.[90]

Oceanic traditions

Melanesia

The Urapmin people of the New Guinea Highlands practice a form of group possession known as the "spirit disco" (Tok Pisin: spirit disko).[91] Men and women gather in church buildings, dancing in circles and jumping up and down while women sing Christian songs; this is called "pulling the [Holy] spirit" (Tok Pisin: pulim spirit, Urap: Sinik dagamin).[91][92] The songs' melodies are borrowed from traditional women's songs sung at drum dances (Urap: wat dalamin), and the lyrics are typically in Telefol or other Mountain Ok languages.[92] If successful, some dancers will "get the spirit" (Tok Pisin: kisim spirit), flailing wildly and careening about the dance floor.[91] After an hour or more, those possessed will collapse, the singing will end, and the spirit disco will end with a prayer and, if there is time, a Bible reading and sermon.[91] The body is believed to normally be "heavy" (Urapmin: ilum) with sin, and possession is the process of the Holy Spirit throwing the sins from one's body, making the person "light" (fong) again.[91] This is a completely new ritual for the Urapmin, who have no indigenous tradition of spirit-possession.[91]

Micronesia

The concept of spirit possession appears in Chuuk State, one of the four states of Federated States of Micronesia. Although Chuuk is an overwhelmingly Christian society, traditional beliefs in spirit possession by the dead still exist, usually held by women, and "events" are usually brought on by family conflicts. The supposed spirits, speaking through the women, typically admonish family members to treat each other better.[93]

European traditions

Italian folk magic

In traditional Italian folk magic spirit possessions are not uncommon. It is known in this culture that a person may be possessed by multiple entities at once. The way to be rid of the spirit(s) would be to call for a curatoro, guaritoro or practico which all translate to healer or knowledgeable one from Italian. These healers would perform sacred rituals to be rid of the spirits; the rituals are passed down through generations and vary based on the region in Italy. It is said that for many Italian rituals specifically those to be rid of negative spirits, that the information may only be shared on Christmas Eve (specifically for il malocchio). If the family is religious they may even call in a priest to perform a traditional catholic exorcism on the spirit(s).[94]

Shamanic traditions

Shamanism is a religious practice that involves a practitioner who is believed to interact with a spirit world through altered states of consciousness, such as trance.[95][96] The goal of this is usually to direct these spirits or spiritual energies into the physical world, for healing or another purpose.[95]

New religious movements

Scientific views

Cultural anthropology

The works of Jean Rouch, Germaine Dieterlen, and Marcel Griaule have been extensively cited in research studies on possession in Western Africa that extended to Brazil and North America due to the slave trade.[98][99]

The anthropologist I.M. Lewis noted that women are more likely to be involved in spirit possession cults than men are, and postulated that such cults act as a means of compensation for their exclusion from other spheres within their respective cultures.[100]

Physical anthropology

Anthropologists Alice B. Kehoe and Dody H. Giletti argued that the reason that women are more commonly seen in Afro-Eurasian spirit possession cults is because of deficiencies in thiamine, tryptophan-niacin, calcium, and vitamin D. They argued that a combination of poverty and food taboos cause this problem, and that it is exacerbated by the strains of pregnancy and lactation. They postulated that the involuntary symptoms of these deficiencies affecting their nervous systems have been institutionalized as spirit possession.[101]

Medicine and psychology

Spirit possession (of any kind, including demonic possession) is not a psychiatric or medical diagnosis recognized by either the DSM-5 or the ICD-10.[102] However, in clinical psychiatry, trance and possession disorders are defined as "states involving a temporary loss of the sense of personal identity and full awareness of the surroundings" and are generally classed as a type of dissociative disorder.[103]

People alleged to be possessed by spirits sometimes exhibit symptoms similar to those associated with mental illnesses such as psychosis, catatonia, hysteria, mania, Tourette's syndrome, epilepsy, schizophrenia, or dissociative identity disorder,[104][105][106] including involuntary, uncensored behavior, and an extra-human, extra-social aspect to the individual's actions.[107] It is not uncommon to ascribe the experience of sleep paralysis to demonic possession, although it's not a physical or mental illness.[108] Studies have found that alleged demonic possessions can be related to trauma.[109]

In entry article on Dissociative Identity Disorder, the DSM-5 states, "possession-form identities in dissociative identity disorder typically manifest as behaviors that appear as if a 'spirit,' supernatural being, or outside person has taken control such that the individual begins speaking or acting in a distinctly different manner".[110] The symptoms vary across cultures.[103] The DSM-5 indicates that personality states of dissociative identity disorder may be interpreted as possession in some cultures, and instances of spirit possession are often related to traumatic experiences—suggesting that possession experiences may be caused by mental distress.[109] In cases of dissociative identity disorder in which the alter personality is questioned as to its identity, 29 percent are reported to identify themselves as demons.[111] A 19th century term for a mental disorder in which the patient believes that they are possessed by demons or evil spirits is demonomania or cacodemonomanis.[112]

Some have expressed concern that belief in demonic possession can limit access to health care for the mentally ill.[113]

Notable examples

Purported demonic possessions

In chronological order:

- Martha Brossier (1578)

- Aix-en-Provence possessions (1611)

- Mademoiselle Elizabeth de Ranfaing (1621)

- Loudun possessions (1634)

- Dorothy Talbye trial (1639)

- Louviers possessions (1647)

- The Possession of Elizabeth Knapp (1671)

- George Lukins (1788)

- Gottliebin Dittus (1842)

- Antoine Gay (1871)

- Johann Blumhardt (1842)

- Clara Germana Cele (1906)

- Exorcism of Roland Doe (1940)

- Anneliese Michel (1968)

- Michael Taylor (1974)

- Arne Cheyenne Johnson (1981)

- Tanacu exorcism (2005)

See also

- Automatic writing

- Body hopping

- Demonology

- Divine madness

- Enthusiasm

- Jamaican Maroon spirit-possession language

- List of exorcists

- Necromancy

- Spirit spouse

- Spiritualist Church

- The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner

- Unclean spirit

- Walk-in

References

- Jones (2005), p. 8687.

- Mark 5:9, Luke 8:30

- Santiago, Christopher (Autumn 2021). Costa, Luiz; Ferme, Marianne; Kaur, Raminder; Kipnis, Andrew B. (eds.). "Twilight states: Comparing case studies of hysteria and spirit possession". HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory. University of Chicago Press. 11 (2): 635–659. doi:10.1086/715812. ISSN 2049-1115.

- Bourguignon & Ucko (1969).

- Robbins (2004a), pp. 117–143.

- "The New Testament". Bible Gateway. 2011. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- Rodríguez (1998), pp. 5–7.

- Malachi (1976), p. 462.

- "John 13:27". Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges – via Bible Hub.

- Luke 4:33-35

- Catechism of the Catholic Church, paragraph 328.

- Catechism of the Catholic Church, paragraph 330.

- Amorth (1999), p. 33.

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Wilkinson (2007), p. 25.

- Baglio (2009).

- New Catholic Encyclopedia Supplement. Detroit, MI: Gale. 2009. p. 359.

- Netzley (2002).

- Warren (2019), p. 69.

- Warren (2019), p. 84-86.

- Broedel, 2003 & pp32-33.

- One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Energici". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 9 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 398.

- Showalter (2021).

- Cuneo (1999).

- Tennant (2001).

- Diem & Schöller (2004), p. 144.

- Westermarck (2014), pp. 263–264.

- Chodkiewicz (2012).

- Krawietz, B. (2021). Islam, Migration and Jinn: Spiritual Medicine in Muslim Health Management. Deutschland: Springer International Publishing. p. 67

- Dein (2013), pp. 290–293.

- Rassool (2015).

- Bulkeley, Adams & Davis (2009).

- Maʻrūf (2007), p. 2.

- Al-Krenawi & Graham (1997), p. 211.

- Islam, F., Campbell, R.A. "Satan Has Afflicted Me!" Jinn-Possession and Mental Illness in the Qur'an. J Relig Health 53, 229–243 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-012-9626-5

- Meldon (1908), pp. 123–146.

- Sells (1996), p. 143.

- Griffel (2005), p. 103.

- Szombathy (2014).

- Bohak (2008), p. .

- Wahlen (2004), p. 19.

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- "Demons and demonology". Jewish Virtual Library. 2008. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- "Dybbuk". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- "Dybbuk". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- "Dybbuk", Encyclopædia Britannica Online, retrieved 10 June 2009

- ETUDES AEQUATORIA·6 JEBOLA Textes, rites et signification Thérapie traditionnelle mongo Piet KORSE MONDJULU Lokonga BONGONDO Bonje wa Mpay Centre IEquatoria B. P. 276 Bamanya -Mbandaka-Zaire 1990

- Lambek, Michael (1998). Bodies and persons: comparative perspectives from Africa and Melanesia. Cambridge, U.K. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-521-62737-5. OCLC 39035692.

- Shack (1971), pp. 40–43.

- Hamer & Hamer (1966).

- Gomm (1975).

- McIntosh (2004).

- Lambek (1988), pp. 710–731.

- Igreja & Dias-Lambranca (2008), pp. 353–371.

- Allen (1991), pp. 370–399.

- Tanner (1955), pp. 274–279.

- Alpers (1984), pp. 677–702.

- O'Connell (1982), pp. 21–37.

- Verter (1999), p. 187.

- Pollitzer, William (2005). The Gullah People and Their African Heritage. University of Georgia Press. p. 138. ISBN 9780820327839.

- Harper, Peggy. "African Dance". Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- Fernandez Olmos; Paravisini-Gebert (1997). Sacred Possessions Vodou, Santería, Obeah, and the Caribbean. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9780813523613.

- Fernandez Olmos; Paravisini-Gebert (1997). Sacred Possessions Vodou, Santería, Obeah, and the Caribbean. Rutgers University Press. pp. 19–22. ISBN 9780813523613.

- Hayes (2008), pp. 1–21.

- Opala. "Gullah Customs and Traditions" (PDF). Yale University. Yale University. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- Jacobs (1989). "Spirit Guides and Possession in the New Orleans Black Spiritual Churches". The Journal of American Folklore. 102 (403): 46–48. doi:10.2307/540080. JSTOR 540080. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- Wortham, Robert (2017). W. E. B. Du Bois and the Sociology of the Black Church and Religion, 1897–1914. Lexington Books. p. 153. ISBN 9781498530361.

- Hucks (2003). "African-Derived American Religions". Religion and American Cultures an Encyclopedia of Traditions, Diversity, and Popular Expressions · Volume 1: 20.

- Hazzard-Donald, Katrina (2011). "Hoodoo Religion and American Dance Traditions: Rethinking the Ring Shout" (PDF). The Journal of Pan African Studies. 4 (6): 203. Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- Lincoln, C. Eric (1990). The Black Church in the African American Experience. Duke University Press. pp. 5–8. ISBN 9780822310730.

- Pollitzer, William (2005). The Gullah People and Their African Heritage. University of Georgia Press. pp. 8, 138, 142. ISBN 9780820327839.

- Stuckey, Sterling (2006). "Reflections on the Scholarship of African Origins and Influence in American Slavery". The Journal of African American History. 91 (4): 438–440. doi:10.1086/JAAHv91n4p425. JSTOR 20064125. S2CID 140776130. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- Hazzard-Donald, Katrina (2011). "Hoodoo Religion and American Dance Traditions: Rethinking the Ring Shout" (PDF). The Journal of Pan African Studies. 4 (6): 203. Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- Ferguson. "Magic Bowls". African American Heritage and Ethnography. National Park Service. Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- Strickmann (2002), p. 251.

- Sutherland (2013).

- "Tibetan Buddhist Psychology and Psychotherapy". Tibetan Medicine Education center. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- Kinnard (2006).

- Buswell & Lopez (2013).

- "Four maras". Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive. 2019. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- Oxtoby & Amore (2010), pp. 256–319.

- "朱秀華借屍回陽記".

- "豐原鎮天宮全球資訊網".

- "Spirit-Writing and the Development of Chinese Cults".

- Snodgrass (2002), pp. 32–64.

- Nabokov (1997), pp. 297–316.

- Dart (1990), p. 83.

- Broch (1985), pp. 262–282.

- Woodward, Mark. Java, Indonesia and Islam. Deutschland, Springer Netherlands, 2010. p. 88

- Ong (1988), pp. 28–42.

- Robbins (1998), pp. 299–316.

- Robbins (2004b), p. 284.

- Hezel (1993).

- Witchcraft, healing and vernacular magic in Italy. Manchester University Press. January 2020. ISBN 9781526137975.

- Singh, Manvir (2018). "The cultural evolution of shamanism". Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 41: e66: 1–61. doi:10.1017/S0140525X17001893. PMID 28679454. S2CID 206264885.

- Mircea Eliade; Vilmos Diószegi (12 May 2020). "Shamanism". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

Shamanism, religious phenomenon centred on the shaman, a person believed to achieve various powers through trance or ecstatic religious experience. Although shamans' repertoires vary from one culture to the next, they are typically thought to have the ability to heal the sick, to communicate with the otherworld, and often to escort the souls of the dead to that otherworld.

- Adler (1997), p. .

- Queiroz (2012), pp. 184–211.

- De Heusch (2007), pp. 365–386.

- Lewis, 1966 & 307–329.

- Kehoe & Giletti (1981), pp. 549–561.

- Henderson (1981), pp. 129–134.

- Bhasvar, Ventriglio & Dinesh (2016), pp. 551–559.

- "How Exorcism Works". 8 September 2005.

- Goodwin (1990), pp. 94–101.

- Ferracuti & Sacco (1996), pp. 525–539.

- Strickmann (2002), p. 65.

- Beyerstein (1995), pp. 544–552.

- Braitmayer, Hecker & Van Duijl (2015).

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing. 2013. pp. 293. ISBN 978-0-89042-554-1.

- Erlendsson (2003).

- Noll (2009).

- Karanci (2014).

Bibliography

- Adler, Margo (1997). Drawing Down the Moon. Penguin.

- Allen, Tim (July 1991). "Understanding Alice: Uganda's Holy Spirit Movement in context". Africa. 61 (3): 370–399. doi:10.2307/1160031. JSTOR 1160031. S2CID 145668917.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Al-Krenawi, A.; Graham, J.R. (1997). "Spirit Possession and Exorcism in the Treatment of a Bedouin Psychiatric Patient". Clinical Social Work Journal. 25 (2): 211. doi:10.1023/A:1025714626136. S2CID 140937987.

- Alpers, Edward A. (1984). "'Ordinary Household Chores': Ritual and Power in a 19th-Century Swahili Women's Spirit Possession Cult". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 17 (4): 677–702. doi:10.2307/218907. JSTOR 218907.

- Amorth, Gabriele (1999). An Exorcist Tells his Story. Translated by MacKenzie, Nicoletta V. San Francisco: Ignatius Press. p. 33.

- Baglio, Matt (2009). The Rite: The Making of a Modern Exorcist. New York: Doubleday.

- Beyerstein, Barry L. (1995). "Dissociative States: Possession and Exorcism". In Stein, Gordon (ed.). The Encyclopedia of the Paranormal. Prometheus Books. pp. 544–552. ISBN 1-57392-021-5.

- Bhavsar, Vishal; Ventriglio, Antonio; Dinesh, Bhugra (2016). "Dissociative trance and spirit possession: Challenges for cultures in transition". Japanese Society of Psychiatry and Neurology. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 70 (12): 551–559. doi:10.1111/pcn.12425. PMID 27485275. S2CID 24609757.

- Bohak, Gideon (2008). Ancient Jewish magic: a history.

- Bourguignon, Erika; Ucko, Lenora (1969). Cross-Cultural Study of Dissociational States. The Ohio State University Research Foundation with National Institute of Mental Health grant.

- Braitmayer, Lars; Hecker, Tobias; Van Duijl, Marjolein (2015). "Global mental health and trauma exposure: The current evidence for the relationship between traumatic experiences and spirit possession". European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 6: 29126. doi:10.3402/ejpt.v6.29126. PMC 4654771. PMID 26589259.

- Broch, Harald Beyer (1985). "'Crazy Women are Performing in Sombali': A Possession-Trance Ritual on Bonerate, Indonesia". Ethos. 13 (3): 262–282. doi:10.1525/eth.1985.13.3.02a00040. JSTOR 640005.

- Broedel, Hans Peter (2003). The Malleus Maleficarum and the Construction of Witchcraft. Great Britain: Manchester University Press. pp. 32–33. ISBN 9780719064418.

- Bulkeley, Kelly; Adams, Kate; Davis, Patricia M., eds. (2009). Dreaming in Christianity and Islam: Culture, Conflict, and Creativity. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-813-54610-0.

- Buswell, Robert Jr.; Lopez, Donald S.Jr., eds. (2013). Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 530–531, 550, 829. ISBN 9780691157863.

- Calmet, Augustine (1751). Treatise on the Apparitions of Spirits and on Vampires or Revenants: of Hungary, Moravia, et al. The Complete Volumes I & II. 2016. ISBN 978-1-5331-4568-0.

- Chodkiewicz, M. (2012). "Rūḥāniyya". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.). doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_6323. ISBN 978-90-04-16121-4.

- Cuneo, Michael (1999). "Exorcism". Contemporary American Religion. Gale eBooks. Vol. 1. Macmillan Reference USA. pp. 243–245. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- Dart, Jon Anderson (1990). Dharmadasa, Karuna N.O.; De Alwis Samarasinghe, S.W.R. (eds.). The Vanishing aborigines : Sri Lanka's Veddas in transition. New Delhi: International Centre for Ethnic Studies in association with NORAD and Vikas Pub. House. p. 83. ISBN 978-0706952988.

- De Heusch, Luc (2 October 2007). "Jean Rouch and the Birth of Visual Anthropology: A Brief History of the Comité international du film ethnographique". Visual Anthropology. 20 (5): 365–386. doi:10.1080/08949460701424155. S2CID 143785372.

- Dein, S. (2013). "Jinn and mental health: Looking at jinn possession in modern psychiatric practice". The Psychiatrist. 37 (9): 290–293. doi:10.1192/pb.bp.113.042721. S2CID 29032393.

- Diem, Werner; Schöller, Marco (2004). The Living and the Dead in Islam: Epitaphs as texts. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 144. ISBN 9783447050838.

- Erlendsson, Haraldur (2003). "Multiple Personality Disorder - Demons and Angels or Archetypal aspects of the inner self".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Ferracuti, Stefano; Sacco, Roberto; Lazzari, R (June 1996). "Dissociative Trance Disorder: Clinical and Rorschach Findings in Ten Persons Reporting Demon Possession and Treated by Exorcism". Journal of Personality Assessment. 66 (3): 525–539. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa6603_4. PMID 8667145.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Gomm, Roger (1975). "Bargaining from Weakness: Spirit Possession on the South Kenya Coast". Man. 10 (4): 530–543. doi:10.2307/2800131. JSTOR 2800131.

- Goodwin, Jean; Hill, Sally; Attias, Reina (June 1990). "Historical and folk techniques of exorcism: applications to the treatment of dissociative disorders". Dissociation. 3 (2): 94–101. hdl:1794/1530.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Griffel, Frank (2005). Islam and rationality : the impact of al-Ghazālī : papers collected on his 900th anniversary. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill. p. 103. ISBN 978-9-004-29095-2.

- Hamer, John; Hamer, Irene (1966). "Spirit Possession and Its Socio-Psychological Implications among the Sidamo of Southwest Ethiopia". Ethnology. 5 (4): 392–408. doi:10.2307/3772719. JSTOR 3772719.

- Hayes, Kelly E. (August 2008). "Wicked Women and Femmes Fatales: Gender, Power, and Pomba Gira in Brazil". History of Religions. 48 (1): 1–21. doi:10.1086/592152. S2CID 162196759.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Henderson, J. (1981). "Exorcism and Possession in Psychotherapy Practice". 2. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry: 129–134.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Hezel, Francis X. (1993). "Spirit Possession in Chuuk: Socio-Cultural Interpretation". 11. Micronesian Counselor.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Igreja, Victor; Dias-Lambranca, Béatrice; Richters, Annemiek (June 2008). "Gamba spirits, gender relations, and healing in post-civil war Gorongosa, Mozambique". Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 14 (2): 353–371. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9655.2008.00506.x.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Jones, Lindsay (2005). Encyclopedia of Religion. Vol. 13 (2 ed.). Detroit, MI: Macmillan Reference USA. p. 8687. ISBN 0-02-865733-0.

- Karanci, A. Nuray (2014). "Concerns About Schizophrenia or Possession?". Journal of Religion and Health. 53 (6): 1691–1692. doi:10.1007/s10943-014-9910-7. PMID 25056667. S2CID 34949947.

- Kehoe, Alice B.; Giletti, Dody H. (September 1981). "Women's Preponderance in Possession Cults: The Calcium-Deficiency Hypothesis Extended". American Anthropologist. 83 (3): 549–561. doi:10.1525/aa.1981.83.3.02a00030.

- Kinnard, Jacob (2006). Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practice. Gale Virtual Reference Library: Gale.

- Lambek, Michael (November 1988). "spirit possession/spirit succession: aspects of social continuity among Malagasy speakers in Mayotte". American Ethnologist. 15 (4): 710–731. doi:10.1525/ae.1988.15.4.02a00070.

- Lewis, I. M. (1966). "Spirit Possession and Deprivation Cults". Man. 1 (3): 307–329. doi:10.2307/2796794. JSTOR 2796794.

- Maʻrūf, Muḥammad (2007). Jinn Eviction as a Discourse of Power: A Multidisciplinary Approach to Modern Morrocan Magical Beliefs and Practices. Brill. p. 2. ISBN 9789004160996.

- Malachi, M. (1976). Hostage to the Devil: the possession and exorcism of five living Americans. San Francisco: Harpercollins. p. 462. ISBN 0-06-065337-X.

- Meldon, J.A. (1908). "Notes on the Sudanese in Uganda". Journal of the Royal African Society. 7 (26): 123–146. JSTOR 715079.

- McIntosh, Janet (March 2004). "Reluctant Muslims: embodied hegemony and moral resistance in a Giriama spirit possession complex". Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 10 (1): 91–112. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9655.2004.00181.x.

- Nabokov, Isabelle (1997). "Expel the Lover, Recover the Wife: Symbolic Analysis of a South Indian Exorcism". The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 3 (2): 297–316. doi:10.2307/3035021. JSTOR 3035021.

- Netzley, Patricia D. (2002). The Greenhaven Encyclopedia of Witchcraft. San Diego, CA: Greenhaven Press. p. 206. ISBN 9780737746389.

- Noll, Richard (2009). The Encyclopedia of Schizophrenia and Other Psychotic Disorders. Infobase Publishing. pp. 129–. ISBN 978-0-8160-7508-9.

- O'Connell, M. C. (1982). "Spirit Possession and Role Stress among the Xesibe of Eastern Transkei". Ethnology. 21 (1): 21–37. doi:10.2307/3773703. JSTOR 3773703.

- Ong, Aihwa (February 1988). "the production of possession: spirits and the multinational corporation in Malaysia". American Ethnologist. 15 (1): 28–42. doi:10.1525/ae.1988.15.1.02a00030. S2CID 30121345.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Oxtoby; Amore, eds. (2010). World Religions: Eastern Traditions (3 ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 9, 256–319.

- Queiroz, Ruben Caixeta de (December 2012). "Between the sensible and the intelligible: Anthropology and the cinema of Marcel Mauss and Jean Rouch". Vibrant: Virtual Brazilian Anthropology. 9 (2): 184–211. doi:10.1590/S1809-43412012000200007.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Rassool, G. Hussein (2015). Islamic Counselling: An Introduction to theory and practice. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-44124-3.

- Robbins, Joel (1998). "Becoming Sinners: Christianity and Desire among the Urapmin of Papua New Guinea". Ethnology. 37 (4): 299–316. doi:10.2307/3773784. JSTOR 3773784.

- Robbins, Joel (2004a). "The globalization of pentecostal and charismatic Christianity". Annual Review of Anthropology. 33: 117–143. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.32.061002.093421. ProQuest 199862299.

- Robbins, Joel (2004b). Becoming Sinners: Christianity and Moral Torment in a Papua New Guinea Society. University of California Press. p. 284. ISBN 0-520-23800-1.

- Ángel Manuel Rodríguez (1998), "Old Testament demonology", Ministry: International Journal for Pastors, 7 (6): 5–7, retrieved 29 October 2017

- Sells, Michael Anthony (1996). Early Islamic Mysticism: Sufi, Qurʼan, Miraj, Poetic and Theological Writings. Paulist Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-809-13619-3.

- Shack, William A. (1971). "Hunger, Anxiety, and Ritual: Deprivation and Spirit Possession Among the Gurage of Ethiopia". Man. 6 (1): 30–43. doi:10.2307/2798425. JSTOR 2798425.

- Showalter, Brandon (26 May 2021). "UK Baptist group warns against occultism amid rise in grief-stricken seeking to contact the dead". The Christian Post. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- Snodgrass, Jeffrey G. (2002). "Imitation Is Far More than the Sincerest of Flattery: The Mimetic Power of Spirit Possession in Rajasthan, India". Cultural Anthropology. 17 (1): 32–64. doi:10.1525/can.2002.17.1.32. JSTOR 656672.

- Strickmann, Michel (2002). Faure, Bernard (ed.). Chinese Magical Medicine. Stanford University Press. pp. 65, 251.

- Sutherland, Gail Hinich (2013). "Demons and the Demonic in Buddhism". Oxford Bibliographies. doi:10.1093/OBO/9780195393521-0171. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- Szombathy, Zoltan (2014). "Exorcism". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Vol. 3. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_26268. ISBN 9789004269637.

- Tanner, R.E.S. (1955). "Hysteria in Sukuma Medical Practice". Africa: Journal of the International African Institute. 25 (3): 274–279. doi:10.2307/1157107. JSTOR 1157107. S2CID 145594255.

- Tennant, Agnieszka (3 September 2001). "In need of deliverance". Christianity Today. 45: 46–48+. ProQuest 211985417.

- Verter, Bradford (1999). Contemporary American Religions. Gale eBooks: Macmillan Reference USA. p. 187.

- Wahlen, Clinton (2004). Jesus and the impurity of spirits in the Synoptic Gospels. p. 19.

The Jewish magical papyri and incantation bowls may also shed light on our investigation. However, the fact that all of these sources are generally dated from the third to fifth centuries and beyond requires us to exercise particular ...

- Warren, Brett (2019). The Annotated Daemonologie: A Critical Edition. ISBN 978-1532968914.

- Westermarck, Edward (23 April 2014). Ritual and Belief in Morocco. Routledge Revivals. Vol. 1. Routledge. pp. 263–264. ISBN 9781317912682.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Wilkinson, Tracy (2007). The Vatican's Exorcists. New York: Warner Books. p. 25.