Indigenous peoples of the Americas

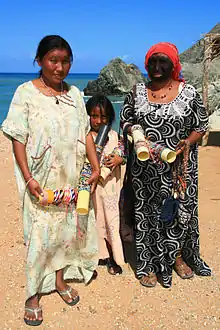

The Indigenous peoples of the Americas are the inhabitants of the Americas before the arrival of the European settlers in the 15th century, and the ethnic groups who now identify themselves with those peoples.

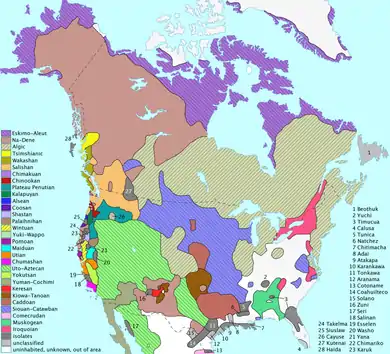

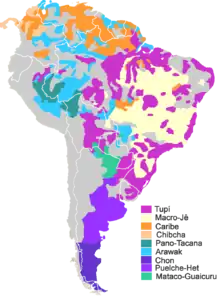

Current distribution of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas (not including mixed people like mestizos, métis, zambos and pardos) | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| ~54 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 11.8–23.2 million[1][2] | |

| 6.4 million[3] | |

| 5.9 million[4] | |

| 4.1 million[5] | |

| 3.7 million[6] | |

| 2.1 million[7] | |

| 1.9 million[8] | |

| 1.8 million[9] | |

| 1 million[10] | |

| 955,032[11] | |

| 817,963[12] | |

| 724,592[13] | |

| 601,019[14] | |

| 443,847[15] | |

| 417,559[16] | |

| 117,150[17] | |

| 104,143[18] | |

| 78,492[19] | |

| 76,452[20] | |

| 50,189[21] | |

| 36,507[22] | |

| 20,344[23] | |

| 19,839[24] | |

| ~19,000[25] | |

| 13,310[26] | |

| 3,280[27] | |

| 2,576[28] | |

| ~1,600[29] | |

| 1,394[30] | |

| 162[31] | |

| Religion | |

| Mostly Christianity (Catholic and Protestant), along with various Indigenous American religions | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Mestizos, Métis, Zambos, Pardos, and Indigenous Siberian peoples | |

Many Indigenous peoples of the Americas were traditionally hunter-gatherers and many, especially in the Amazon basin, still are, but many groups practiced aquaculture and agriculture.[32] While some societies depended heavily on agriculture, others practiced a mix of farming, hunting, and gathering. In some regions, the Indigenous peoples created monumental architecture, large-scale organized cities, city-states, chiefdoms, states, kingdoms, republics,[33] confederacies, and empires. Some had varying degrees of knowledge of engineering, architecture, mathematics, astronomy, writing, physics, medicine, planting and irrigation, geology, mining, metallurgy, sculpture, and gold smithing.

Many parts of the Americas are still populated by Indigenous peoples; some countries have sizeable populations, especially Bolivia, Canada, Chile, Ecuador, Guatemala, Mexico, Peru and the United States. At least a thousand different Indigenous languages are spoken in the Americas. Some, such as the Quechuan languages, Arawak language, Aymara, Guaraní, Mayan languages, and Nahuatl, count their speakers in the millions. Many also maintain aspects of Indigenous cultural practices to varying degrees, including religion, social organization, and subsistence practices. Like most cultures, over time, cultures specific to many Indigenous peoples have evolved to incorporate traditional aspects but also cater to modern needs. Some Indigenous peoples still live in relative isolation from Western culture and a few are still counted as uncontacted peoples.

Terminology

_2007.jpg.webp)

Application of the term "Indian" originated with Christopher Columbus, who, in his search for India, thought that he had arrived in the East Indies.[34][35][36][37][38][39] Eventually, those islands came to be known as the "West Indies", a name still used. This led to the blanket term "Indies" and "Indians" (Spanish: indios; Portuguese: índios; French: indiens; Dutch: indianen) for the Indigenous inhabitants, which implied some kind of ethnic or cultural unity among the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. This unifying concept, codified in law, religion, and politics, was not originally accepted by the myriad groups of Indigenous peoples themselves, but has since been embraced or tolerated by many over the last two centuries.[40] Even though the term "Indian" generally does not include the culturally and linguistically distinct Indigenous peoples of the Arctic regions of the Americas—such as the Aleuts, Inuit, or Yupik peoples, who entered the continent as a second, more recent wave of migration several thousand years later and have much more recent genetic and cultural commonalities with the Aboriginal peoples of the Asiatic Arctic Russian Far East—these groups are nonetheless considered "Indigenous peoples of the Americas".

The term Amerindian, a portmanteau of "American Indian", was coined in 1902 by the American Anthropological Association. However, it has been controversial since its creation. It was immediately rejected by some leading members of the Association, and, while adopted by many, it was never universally accepted.[41] While never popular in Indigenous communities themselves, it remains a preferred term among some anthropologists, notably in some parts of Canada and the English-speaking Caribbean.[42][43][44][45]

Indigenous peoples in Canada is used as the collective name for First Nations, Inuit, and Métis.[46][47] The term Aboriginal peoples as a collective noun (also describing First Nations, Inuit, and Métis) is a specific term of art used in some legal documents, including the Constitution Act, 1982,[48] though in most Indigenous circles Aboriginal has also fallen into disfavor.[49] Over time, as societal perceptions and government-Indigenous relationships have shifted, many historical terms have changed definition or been replaced as they have fallen out of favor.[50] Use of the term "Indian" is frowned upon because it represents the imposition and restriction of Indigenous peoples and cultures by the Canadian Government.[50] The terms "Native" and "Eskimo" are generally regarded as disrespectful, and so are rarely used unless specifically required.[51] While "Indigenous peoples" is the preferred term, many individuals or communities may choose to self-describe their identity using a different term.[50][51]

The Métis people of Canada can be contrasted, for instance, to the Indigenous-European mixed race mestizos (or caboclos in Brazil) of Hispanic America who, with their larger population (in most Latin-American countries constituting either outright majorities, pluralities, or at the least large minorities), identify largely as a new ethnic group distinct from both Europeans and Indigenous, but still considering themselves a subset of the European-derived Hispanic or Brazilian peoplehood in culture and ethnicity (cf. ladinos).

Among Spanish-speaking countries, indígenas or pueblos indígenas ('Indigenous peoples') is a common term, though nativos or pueblos nativos ('native peoples') may also be heard; moreover, aborigen ('aborigine') is used in Argentina and pueblos originarios ('original peoples') is common in Chile. In Brazil, indígenas or povos indígenas ('Indigenous peoples') are common of formal-sounding designations, while índio ('Indian') is still the more often-heard term (the noun for the South-Asian nationality being indiano). Aborígene and nativo is rarely used in Brazil in Indigenous-specific contexts (e.g., aborígene is usually understood as the ethnonym for Indigenous Australians). The Spanish and Portuguese equivalents to Indian, nevertheless, could be used to mean any hunter-gatherer or full-blooded Indigenous person, particularly to continents other than Europe or Africa—for example, indios filipinos.

Indigenous peoples of the United States are commonly known as Native Americans, Indians, as well as Alaska Natives. The term "Indian" is still used in some communities and remains in use in the official names of many institutions and businesses in Indian Country.[52]

Native American name controversy

The various Nations, tribes, and bands of Indigenous peoples of the Americas have differing preferences in terminology for themselves.[53] While there are regional and generational variations in which umbrella terms are preferred for Indigenous peoples as a whole, in general, most Indigenous peoples prefer to be identified by the name of their specific Nation, tribe, or band.[53][54]

Early settlers often adopted terms that some tribes used for each other, not realizing these were derogatory terms used by enemies. When discussing broader subsets of peoples, naming has often been based on shared language, region, or historical relationship.[55] Many English exonyms have been used to refer to the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. Some of these names were based on foreign-language terms used by earlier explorers and colonists, while others resulted from the colonists' attempts to translate or transliterate endonyms from the native languages. Other terms arose during periods of conflict between the colonists and Indigenous peoples.[56]

Since the late 20th century, Indigenous peoples in the Americas have been more vocal about how they want to be addressed, pushing to suppress use of terms widely considered to be obsolete, inaccurate, or racist. During the latter half of the 20th century and the rise of the Indian rights movement, the United States government responded by proposing the use of the term "Native American", to recognize the primacy of Indigenous peoples' tenure in the nation.[57] As may be expected among people of over 400 different cultures in the US alone, not all of the people intended to be described by this term have agreed on its use or adopted it. No single group naming convention has been accepted by all Indigenous peoples in the Americas. Most prefer to be addressed as people of their tribe or nations when not speaking about Native Americans/American Indians as a whole.[58]

Since the 1970s, Indigenous (capitalized when referring to people) has gradually emerged as a favored umbrella term. The capitalization is to acknowledge that Indigenous peoples have cultures and societies that are equal to Europeans, Africans, and Asians.[54][59] This has recently been acknowledged in the AP Stylebook.[60] Some consider it improper to refer to Indigenous people as "Indigenous Americans" or to append any colonial nationality to the term because Indigenous cultures have existed prior to European colonization. Indigenous groups have territorial claims that are different from modern national and international borders, and when labelled as part of a country, their traditional lands are not acknowledged. Some who have written guidelines consider it more appropriate to describe an Indigenous person as "living in" or "of" the Americas, rather than calling them "American"; or to simply call them "Indigenous" without any addition of a colonial state.[61][62]

History

Settlement of the Americas

The settlement of the Americas began when Paleolithic hunter-gatherers entered North America from the North Asian Mammoth steppe via the Beringia land bridge, which had formed between northeastern Siberia and western Alaska due to the lowering of sea level during the Last Glacial Maximum (26,000 to 19,000 years ago).[64] These populations expanded south of the Laurentide Ice Sheet and spread rapidly southward, occupying both North and South America, by 12,000 to 14,000 years ago.[65][66][67][68][69] The earliest populations in the Americas, before roughly 10,000 years ago, are known as Paleo-Indians. Indigenous peoples of the Americas have been linked to Siberian populations by linguistic factors, the distribution of blood types, and in genetic composition as reflected by molecular data, such as DNA.[70][71]

The precise date for the peopling of the Americas is a long-standing open question, and while advances in archaeology, Pleistocene geology, physical anthropology, and DNA analysis have progressively shed more light on the subject, significant questions remain unresolved.[72] While there is general agreement that the Americas were first settled from Asia, the pattern of migration, its timing, and the place(s) of origin in Eurasia of the peoples who migrated to the Americas remain unclear.[66] The "Clovis first theory" refers to the hypothesis that the Clovis culture represents the earliest human presence in the Americas about 13,000 years ago.[73]

However, evidence of pre-Clovis cultures has accumulated and pushed back the possible date of the first peopling of the Americas.[74][75][76] Many archaeologists believe that humans reached North America south of the Laurentide Ice Sheet at some point between 15,000 and 20,000 years ago.[77][78][79][80] The theory is that these early migrants moved when sea levels were significantly lowered due to the Quaternary glaciation,[81][82] following herds of now-extinct Pleistocene megafauna along ice-free corridors that stretched between the Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets.[83] Another route proposed is that, either on foot or using primitive boats, they migrated down the Pacific coast to South America as far as Chile.[84] Any archaeological evidence of coastal occupation during the last Ice Age would now have been covered by the sea level rise, up to a hundred metres since then.[85] Some archaeological evidence suggests the possibility that human arrival in the Americas may have occurred prior to the Last Glacial Maximum more than 20,000 years ago.[86]Pre-Columbian era

The Pre-Columbian era refers to all period subdivisions in the history and prehistory of the Americas before the appearance of significant European and African influences on the American continents, spanning the time of the original arrival in the Upper Paleolithic to European colonization during the early modern period.[87]

While technically referring to the era before Christopher Columbus' voyages of 1492 to 1504, in practice the term usually includes the history of Indigenous cultures until Europeans either conquered or significantly influenced them.[89] "Pre-Columbian" is used especially often in the context of discussing the pre-contact Mesoamerican Indigenous societies: Olmec; Toltec; Teotihuacano' Zapotec; Mixtec; Aztec and Maya civilizations; and the complex cultures of the Andes: Inca Empire, Moche culture, Muisca Confederation, and Cañari.

The Norte Chico civilization (in present-day Peru) is one of the defining six original civilizations of the world, arising independently around the same time as that of Egypt.[92][93] Many later pre-Columbian civilizations achieved great complexity, with hallmarks that included permanent or urban settlements, agriculture, engineering, astronomy, trade, civic and monumental architecture, and complex societal hierarchies. Some of these civilizations had long faded by the time of the first significant European and African arrivals (ca. late 15th–early 16th centuries), and are known only through oral history and through archaeological investigations. Others were contemporary with the contact and colonization period, and were documented in historical accounts of the time. A few, such as the Mayan, Olmec, Mixtec, Aztec and Nahua peoples, had their own written languages and records. However, the European colonists of the time worked to eliminate non-Christian beliefs, and burned many pre-Columbian written records. Only a few documents remained hidden and survived, leaving contemporary historians with glimpses of ancient culture and knowledge.

According to both Indigenous and European accounts and documents, American civilizations before and at the time of European encounter had achieved great complexity and many accomplishments.[94] For instance, the Aztecs built one of the largest cities in the world, Tenochtitlan (the historical site of what would become Mexico City), with an estimated population of 200,000 for the city proper and a population of close to five million for the extended empire.[95] By comparison, the largest European cities in the 16th century were Constantinople and Paris with 300,000 and 200,000 inhabitants respectively.[96] The population in London, Madrid and Rome hardly exceeded 50,000 people. In 1523, right around the time of the Spanish conquest, the entire population in the country of England was just under three million people.[97] This fact speaks to the level of sophistication, agriculture, governmental procedure and rule of law that existed in Tenochtitlan, needed to govern over such a large citizenry. Indigenous civilizations also displayed impressive accomplishments in astronomy and mathematics, including the most accurate calendar in the world. The domestication of maize or corn required thousands of years of selective breeding, and continued cultivation of multiple varieties was done with planning and selection, generally by women.

Inuit, Yupik, Aleut, and Indigenous creation myths tell of a variety of origins of their respective peoples. Some were "always there" or were created by gods or animals, some migrated from a specified compass point, and others came from "across the ocean".[98]

European colonization

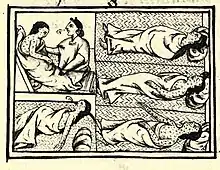

The European colonization of the Americas fundamentally changed the lives and cultures of the resident Indigenous peoples. Although the exact pre-colonization population-count of the Americas is unknown, scholars estimate that Indigenous populations diminished by between 80% and 90% within the first centuries of European colonization. The majority of these losses are attributed to the introduction of Afro-Eurasian diseases into the Americas. Epidemics ravaged the Americas with diseases such as smallpox, measles, and cholera, which the early colonists brought from Europe.

The spread of infectious diseases was slow initially, as most Europeans were not actively or visibly infected, due to inherited immunity from generations of exposure to these diseases in Europe. This changed when the Europeans began the human trafficking of massive numbers of enslaved Western and Central African people to the Americas. Like Indigenous peoples, these African people, newly exposed to European diseases, lacked any inherited resistances to the diseases of Europe. In 1520 an African who had been infected with smallpox had arrived in Yucatán. By 1558, the disease had spread throughout South America and had arrived at the Plata basin.[99] Colonist violence towards Indigenous peoples accelerated the loss of lives. European colonists perpetrated massacres on the Indigenous peoples and enslaved them.[100][101][102] According to the U.S. Bureau of the Census (1894), the North American Indian Wars of the 19th century cost the lives of about 19,000 Europeans and 30,000 Native Americans.[103]

The first Indigenous group encountered by Columbus, the 250,000 Taínos of Hispaniola, represented the dominant culture in the Greater Antilles and the Bahamas. Within thirty years about 70% of the Taínos had died.[104] They had no immunity to European diseases, so outbreaks of measles and smallpox ravaged their population.[105] One such outbreak occurred in a camp of enslaved Africans, where smallpox spread to the nearby Taíno population and reduced their numbers by 50%.[99] Increasing punishment of the Taínos for revolting against forced labor, despite measures put in place by the encomienda, which included religious education and protection from warring tribes,[106] eventually led to the last great Taíno rebellion (1511–1529).

Following years of mistreatment, the Taínos began to adopt suicidal behaviors, with women aborting or killing their infants and men jumping from cliffs or ingesting untreated cassava, a violent poison.[104] Eventually, a Taíno Cacique named Enriquillo managed to hold out in the Baoruco Mountain Range for thirteen years, causing serious damage to the Spanish, Carib-held plantations and their Indian auxiliaries.[107] Hearing of the seriousness of the revolt, Emperor Charles V (also King of Spain) sent captain Francisco Barrionuevo to negotiate a peace treaty with the ever-increasing number of rebels. Two months later, after consultation with the Audencia of Santo Domingo, Enriquillo was offered any part of the island to live in peace.

The Laws of Burgos, 1512–1513, were the first codified set of laws governing the behavior of Spanish settlers in America, particularly with regard to Indigenous peoples. The laws forbade the maltreatment of them and endorsed their conversion to Catholicism.[108] The Spanish crown found it difficult to enforce these laws in distant colonies.

Epidemic disease was the overwhelming cause of the population decline of the Indigenous peoples.[109][110] After initial contact with Europeans and Africans, Old World diseases caused the deaths of 90 to 95% of the native population of the New World in the following 150 years.[111] Smallpox killed from one third to half of the native population of Hispaniola in 1518.[112][113] By killing the Incan ruler Huayna Capac, smallpox caused the Inca Civil War of 1529–1532. Smallpox was only the first epidemic. Typhus (probably) in 1546, influenza and smallpox together in 1558, smallpox again in 1589, diphtheria in 1614, measles in 1618—all ravaged the remains of Inca culture.

Smallpox killed millions of native inhabitants of Mexico.[114][115] Unintentionally introduced at Veracruz with the arrival of Pánfilo de Narváez on 23 April 1520, smallpox ravaged Mexico in the 1520s,[116] possibly killing over 150,000 in Tenochtitlán (the heartland of the Aztec Empire) alone, and aiding in the victory of Hernán Cortés over the Aztec Empire at Tenochtitlan (present-day Mexico City) in 1521.[99]

There are many factors as to why Indigenous peoples suffered such immense losses from Afro-Eurasian diseases. Many European diseases, like cow pox, are acquired from domesticated animals that are not indigenous to the Americas. European populations had adapted to these diseases, and built up resistance, over many generations. Many of the European diseases that were brought over to the Americas were diseases, like yellow fever, that were relatively manageable if infected as a child, but were deadly if infected as an adult. Children could often survive the disease, resulting in immunity to the disease for the rest of their lives. But contact with adult populations without this childhood or inherited immunity would result in these diseases proving fatal.[99][117]

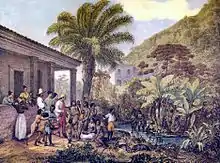

Colonization of the Caribbean led to the destruction of the Arawaks of the Lesser Antilles. Their culture was destroyed by 1650. Only 500 had survived by the year 1550, though the bloodlines continued through to the modern populace. In Amazonia, Indigenous societies weathered, and continue to suffer, centuries of colonization and genocide.[118]

Contact with European diseases such as smallpox and measles killed between 50 and 67 per cent of the Indigenous population of North America in the first hundred years after the arrival of Europeans.[119] Some 90 per cent of the native population near Massachusetts Bay Colony died of smallpox in an epidemic in 1617–1619.[120] In 1633, in Fort Orange (New Netherland), the Native Americans there were exposed to smallpox because of contact with Europeans. As it had done elsewhere, the virus wiped out entire population-groups of Native Americans.[121] It reached Lake Ontario in 1636, and the lands of the Iroquois by 1679.[122][123] During the 1770s smallpox killed at least 30% of the West Coast Native Americans.[124] The 1775–82 North American smallpox epidemic and the 1837 Great Plains smallpox epidemic brought devastation and drastic population depletion among the Plains Indians.[125][126] In 1832 the federal government of the United States established a smallpox vaccination program for Native Americans (The Indian Vaccination Act of 1832).[127]

The Indigenous peoples in Brazil declined from a pre-Columbian high of an estimated three million[128] to some 300,000 in 1997.[129]

The Spanish Empire and other Europeans re-introduced horses to the Americas. Some of these animals escaped and began to breed and increase their numbers in the wild.[130] The re-introduction of the horse, extinct in the Americas for over 7500 years, had a profound impact on Indigenous cultures in the Great Plains of North America and in Patagonia in South America. By domesticating horses, some tribes had great success: horses enabled them to expand their territories, exchange more goods with neighboring tribes, and more easily capture game, especially bison.

Indigenous historical trauma (IHT)

Indigenous historical trauma (IHT) is the trauma that can accumulate across generations that develops as a result of the historical ramifications of colonization and is linked to mental and physical health hardships and population decline.[131] IHT affects many different people in a multitude of ways because the Indigenous community and their history is diverse.

Many studies (such as Whitbeck et al., 2014;[132] Brockie, 2012; Anastasio et al., 2016;[133] Clark & Winterowd, 2012;[134] Tucker et al., 2016)[135] have evaluated the impact of IHT on health outcomes of Indigenous communities from the United States and Canada. IHT is a difficult term to standardize and measure because of the vast and variable diversity of Indigenous people and their communities. Therefore, it is an arduous task to assign an operational definition and systematically collect data when studying IHT. Many of the studies that incorporate IHT measure it in different ways, making it hard to compile data and review it holistically. This is an important point that provides context for the following studies that attempt to understand the relationship between IHT and potential adverse health impacts.

Some of the methodologies to measure IHT include a "Historical Losses Scale" (HLS), "Historical Losses Associated Symptoms Scale" (HLASS), and residential school ancestry studies.[131]: 23 HLS uses a survey format that includes "12 kinds of historical losses," such as loss of language and loss of land and asks participants how often they think about those losses.[131]: 23 The HLASS includes 12 emotional reactions and asks participants how they feel when they think about these losses.[131] Lastly, the residential school ancestry studies ask respondents if their parents, grandparents, great-grandparents or "elders from their community" went to a residential school to understand if family or community history in residential schools are associated with negative health outcomes.[131]: 25 In a comprehensive review of the research literature, Joseph Gone and colleagues[131] compiled and compared outcomes for studies using these IHT measures relative to health outcomes of Indigenous peoples. The study defined negative health outcomes to include such concepts as anxiety, suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, polysubstance abuse, PTSD, depression, binge eating, anger, and sexual abuse.[131]

The connection between IHT and health conditions is complicated because of the difficult nature of measuring IHT, the unknown directionality of IHT and health outcomes, and because the term Indigenous people used in the various samples comprises a huge population of individuals with drastically different experiences and histories. That being said, some studies such as Bombay, Matheson, and Anisman (2014),[136] Elias et al. (2012),[137] and Pearce et al. (2008)[138] found that Indigenous respondents with a connection to residential schools have more negative health outcomes (e.g., suicide ideation, suicide attempts, and depression) than those who did not have a connection to residential schools. Additionally, Indigenous respondents with higher HLS and HLASS scores had one or more negative health outcomes.[131] While there many studies[133][139][134][140][135] that found an association between IHT and adverse health outcomes, scholars continue to suggest that it remains difficult to understand the impact of IHT. IHT needs to be systematically measured. Indigenous people also need to be understood in separated categories based on similar experiences, location, and background as opposed to being categorized as one monolithic group.[131]

Agriculture

Plants

In the course of thousands of years, Indigenous peoples domesticated, bred and cultivated a large array of plant species. These species now constitute between 50% and 60% of all crops in cultivation worldwide.[141] In certain cases, the Indigenous peoples developed entirely new species and strains through artificial selection, as with the domestication and breeding of maize from wild teosinte grasses in the valleys of southern Mexico. Numerous such agricultural products retain their native names in the English and Spanish lexicons.

The South American highlands became a center of early agriculture. Genetic testing of the wide variety of cultivars and wild species suggests that the potato has a single origin in the area of southern Peru,[142] from a species in the Solanum brevicaule complex. Over 99% of all modern cultivated potatoes worldwide are descendants of a subspecies Indigenous to south-central Chile,[143] Solanum tuberosum ssp. tuberosum, where it was cultivated as long as 10,000 years ago.[144][145] According to Linda Newson, "It is clear that in pre-Columbian times some groups struggled to survive and often suffered food shortages and famines, while others enjoyed a varied and substantial diet."[146]

Persistent drought around AD 850 coincided with the collapse of Classic Maya civilization, and the famine of One Rabbit (AD 1454) was a major catastrophe in Mexico.[147]

Indigenous peoples of North America began practicing farming approximately 4,000 years ago, late in the Archaic period of North American cultures. Technology had advanced to the point where pottery had started to become common and the small-scale felling of trees had become feasible. Concurrently, the Archaic Indigenous peoples began using fire in a controlled manner. They carried out intentional burning of vegetation to mimic the effects of natural fires that tended to clear forest understories. It made travel easier and facilitated the growth of herbs and berry-producing plants, which were important both for food and for medicines.[148]

In the Mississippi River valley, Europeans noted that Native Americans managed groves of nut- and fruit-trees not far from villages and towns and their gardens and agricultural fields. They would have used prescribed burning further away, in forest and prairie areas.[149]

Many crops first domesticated by Indigenous peoples are now produced and used globally, most notably maize (or "corn") arguably the most important crop in the world.[150] Other significant crops include cassava; chia; squash (pumpkins, zucchini, marrow, acorn squash, butternut squash); the pinto bean, Phaseolus beans including most common beans, tepary beans and lima beans; tomatoes; potatoes; sweet potatoes; avocados; peanuts; cocoa beans (used to make chocolate); vanilla; strawberries; pineapples; peppers (species and varieties of Capsicum, including bell peppers, jalapeños, paprika and chili peppers); sunflower seeds; rubber; brazilwood; chicle; tobacco; coca; blueberries, cranberries, and some species of cotton.

Studies of contemporary Indigenous environmental management—including of agro-forestry practices among Itza Maya in Guatemala and of hunting and fishing among the Menominee of Wisconsin—suggest that longstanding "sacred values" may represent a summary of sustainable millennial traditions.[151]

Animals

Indigenous peoples also domesticated some animals, such as turkeys, llamas, alpacas, guinea-pigs, and Muscovy ducks.

Culture

Cultural practices in the Americas seem to have been shared mostly within geographical zones where distinct ethnic groups adopting shared cultural traits, similar technologies, and social organizations. An example of such a cultural area is Mesoamerica, where millennia of coexistence and shared development among the peoples of the region produced a fairly homogeneous culture with complex agricultural and social patterns. Another well-known example is the North American plains where until the 19th century several peoples shared the traits of nomadic hunter-gatherers based primarily on buffalo hunting.

Languages

The languages of the North American Indians have been classified into 56 groups or stock tongues, in which the spoken languages of the tribes may be said to centre. In connection with speech, reference may be made to gesture language which was highly developed in parts of this area. Of equal interest is the picture writing especially well developed among the Chippewas and Delawares.[152]

Writing systems

Beginning in the 1st millennium BCE, pre-Columbian cultures in Mesoamerica developed several Indigenous writing systems (independent of any influence from the writing systems that existed in other parts of the world). The Cascajal Block is perhaps the earliest-known example in the Americas of what may be an extensive written text. The Olmec hieroglyphs tablet has been indirectly dated (from ceramic shards found in the same context) to approximately 900 BCE-which is around the same time that the Olmec occupation of San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán began to weaken.[153]

The Maya writing system was logosyllabic (a combination of phonetic syllabic symbols and logograms). It is the only pre-Columbian writing system known to have completely represented the spoken language of its community. It has more than a thousand different glyphs, but a few are variations on the same sign or have the same meaning, many appear only rarely or in particular localities, no more than about five hundred were in use in any given time period, and, of those, it seems only about two hundred (including variations) represented a particular phoneme or syllable.[154][155][156]

The Zapotec writing system, one of the earliest in the Americas,[157] was logographic and presumably syllabic.[157] There are remnants of Zapotec writing in inscriptions on some of the monumental architecture of the period, but so few inscriptions are extant that it is difficult to fully describe the writing system. The oldest example of Zapotec script, dating from around 600 BCE, is on a monument that was discovered in San José Mogote.[158]

Aztec codices (singular codex) are books that were written by pre-Columbian and colonial-era Aztecs. These codices are some of the best primary sources for descriptions of Aztec culture. The pre-Columbian codices are largely pictorial; they do not contain symbols that represent spoken or written language.[159] By contrast, colonial-era codices contain not only Aztec pictograms, but also writing that uses the Latin alphabet in several languages: Classical Nahuatl, Spanish, and occasionally Latin.

Spanish mendicants in the sixteenth century taught Indigenous scribes in their communities to write their languages using Latin letters, and there are a large number of local-level documents in Nahuatl, Zapotec, Mixtec, and Yucatec Maya from the colonial era, many of which were part of lawsuits and other legal matters. Although Spaniards initially taught Indigenous scribes alphabetic writing, the tradition became self-perpetuating at the local level.[160] The Spanish crown gathered such documentation, and contemporary Spanish translations were made for legal cases. Scholars have translated and analyzed these documents in what is called the New Philology to write histories of Indigenous peoples from Indigenous viewpoints.[161]

The Wiigwaasabak, birch bark scrolls on which the Ojibwa (Anishinaabe) people wrote complex geometrical patterns and shapes, can also be considered a form of writing, as can Mi'kmaq hieroglyphics.

Aboriginal syllabic writing, or simply syllabics, is a family of abugidas used to write some Indigenous languages of the Algonquian, Inuit, and Athabaskan language families.

Music and art

Indigenous music can vary between cultures, however there are significant commonalities. Traditional music often centers around drumming and singing. Rattles, clapper sticks, and rasps are also popular percussive instruments, both historically and in contemporary cultures. Flutes are made of river-cane, cedar, and other woods. The Apache have a type of fiddle, and fiddles are also found among a number of First Nations and Métis cultures.

The music of the Indigenous peoples of Central Mexico and Central America, like that of the North American cultures, tend to be spiritual ceremonies. It traditionally includes a large variety of percussion and wind instruments such as drums, flutes, sea shells (used as trumpets) and "rain" tubes. No remnants of pre-Columbian stringed instruments were found until archaeologists discovered a jar in Guatemala, attributed to the Maya of the Late Classic Era (600–900 CE); this jar was decorated with imagery depicting a stringed musical instrument which has since been reproduced. This instrument is one of the very few stringed instruments known in the Americas prior to the introduction of European musical instruments; when played, it produces a sound that mimics a jaguar's growl.[162]

Visual arts by Indigenous peoples of the Americas comprise a major category in the world art collection. Contributions include pottery, paintings, jewellery, weavings, sculptures, basketry, carvings, and beadwork.[163] Because too many artists were posing as Native Americans and Alaska Natives[164] in order to profit from the cachet of Indigenous art in the United States, the U.S. passed the Indian Arts and Crafts Act of 1990, requiring artists to prove that they are enrolled in a state or federally recognized tribe. To support the ongoing practice of American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian arts and cultures in the United States,[165] the Ford Foundation, arts advocates and American Indian tribes created an endowment seed fund and established a national Native Arts and Cultures Foundation in 2007.[166][167]

After the entry of the Spaniards, the process of spiritual conquest was favored, among other things, by the liturgical musical service to which the natives, whose musical gifts came to surprise the missionaries, were integrated. The musical gifts of the natives were of such magnitude that they soon learned the rules of counterpoint and polyphony and even the virtuous handling of the instruments. This helped to ensure that it was not necessary to bring more musicians from Spain, which significantly annoyed the clergy.[168]

The solution that was proposed was not to employ but a certain number of indigenous people in the musical service, not to teach them counterpoint, not to allow them to play certain instruments (brass breaths, for example, in Oaxaca, Mexico) and, finally, not to import more instruments so that the indigenous people would not have access to them. The latter was not an obstacle to the musical enjoyment of the natives, who experienced the making of instruments, particularly rubbed strings (violins and double basses) or plucked (third). It is there where we can find the origin of what is now called traditional music whose instruments they have their own tuning and a typical western structure.[169]

Demography

The following table provides estimates for each country in the Americas of the populations of Indigenous people and those with partial Indigenous ancestry, each expressed as a percentage of the overall population. The total percentage obtained by adding both of these categories is also given.

Note: these categories are inconsistently defined and measured differently from country to country. Some figures are based on the results of population-wide genetic surveys while others are based on self-identification or observational estimation.

| Country | Indigenous | Ref. | Part Indigenous | Ref. | Combined total | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North America | ||||||

| Greenland | 89% | % | 89% | [170] | ||

| Canada | 1.8% | 3.6% | 5.4% | [171] | ||

| Mexico | 7% | 62% | 69% | [172] | ||

| United States | 1.1% | 1.8% | 2.9% | [173] | ||

| Dominican Republic | % | % | % | |||

| Grenada | ~0.4% | ~0% | ~0.4% | [174] | ||

| Haiti | % | % | % | [175] | ||

| Jamaica | % | % | % | |||

| Puerto Rico | 0.4% | [176] | 84% | [177][178] | 84.4% | |

| Saint Kitts and Nevis | % | % | % | |||

| Saint Lucia | % | % | % | |||

| Saint Vincent and the Grenadines |

2% | % | % | [179] | ||

| Trinidad and Tobago | 0.8% | 88% | 88.8% | |||

| Country | Indigenous | Ref. | Part Indigenous | Ref. | Combined total | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| South America | ||||||

| Argentina | 2.38% | [180] | 27% | [181][182] | 27.38% | |

| Bolivia | 20% | 68% | 88% | [183] | ||

| Brazil | 0.4% | 12% | 12.4% | [184] | ||

| Chile | 10.9% | % | % | [185] | ||

| Colombia | 4.4% | [186] | 49% | [187] | 53.4% | |

| Ecuador | 25% | 65% | 90% | [188] | ||

| French Guiana | % | % | % | |||

| Guyana | 10.5% | [189] | % | % | ||

| Paraguay | 1.7% | 95% | 96.7% | [190] | ||

| Peru | 25.8% | 60.2% | 86% | [191] | ||

| Suriname | 2% | [192] | % | % | ||

| Uruguay | 0% | [193] | 2.4% | [194] | 2.4% | |

| Venezuela | 2.7% | 51.6% | 54.3% | [195] | ||

History and status by continent and country

Canada

Indigenous peoples in Canada comprise the First Nations,[196] Inuit[197] and Métis;[198] the descriptors "Indian" and "Eskimo" are falling into disuse. In Canada, it is quite frowned upon to use the name "Indian" in casual conversation.[199] "Eskimo" is considered derogatory in many other places because it was given by non-Inuit and was said to mean "eater of raw meat".[200] Hundreds of Indigenous nations evolved trade, spiritual and social hierarchies. The Métis ethnicity developed a culture during the 18th century after generations of First Nations married European settlers.[201] They were small farmers, hunters and trappers, and usually Catholic and French-speaking.[202] The Inuit had more limited interaction with European settlers during that early period.[203] Various laws, treaties, and legislation have been enacted between European-Canadians and First Nations across Canada. Aboriginal Right to Self-Government provides the opportunity for First Nations to manage their own historical, cultural, political, health care and economic control within their communities.

Although not without conflict, early European interactions in the east with First Nations and Inuit populations were relatively peaceful compared to the later experience of Indigenous peoples in the United States.[204] Combined with a late economic development in many regions,[205] this relatively peaceful history resulted in Indigenous peoples having a fairly strong influence on the early national culture, while preserving their own identity.[206] From the late 18th century, European Canadians (primarily British Canadians and French Canadians) worked to force Indigenous peoples to assimilate into the mainstream European-influenced culture, which they referred to as Canadian culture.[207] The government attempted violent forced integration in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Notable examples here include residential schools.[208]

National Indigenous Peoples Day recognizes the cultures and contributions of Indigenous peoples of Canada.[209] There are currently over 600 recognized First Nations governments or bands encompassing 1,807,250[9] people spread across Canada, with distinctive Indigenous cultures, languages, art, and music.[210][211][212]

Greenland

The Greenlandic Inuit (Kalaallisut: kalaallit, Tunumiisut: tunumiit, Inuktun: inughuit) are the Indigenous and most populous ethnic group in Greenland.[213] This means that Denmark has one officially recognized Indigenous group. the Inuit – the Greenlandic Inuit of Greenland and the Greenlandic people in Denmark (Inuit residing in Denmark).

Approximately 89 percent of Greenland's population of 57,695 is Greenlandic Inuit, or 51,349 people as of 2012.[214][215] Ethnographically, they consist of three major groups:

- the Kalaallit of west Greenland, who speak Kalaallisut

- the Tunumiit of Tunu (east Greenland), who speak Tunumiit oraasiat ("East Greenlandic")

- the Inughuit of north Greenland, who speak Inuktun ("Polar Inuit")

Mexico

The territory of modern-day Mexico was home to numerous Indigenous civilizations prior to the arrival of the Spanish conquistadores: The Olmecs, who flourished from between 1200 BCE to about 400 BCE in the coastal regions of the Gulf of Mexico; the Zapotecs and the Mixtecs, who held sway in the mountains of Oaxaca and the Isthmus of Tehuantepec; the Maya in the Yucatán (and into neighbouring areas of contemporary Central America); the Purépecha in present-day Michoacán and surrounding areas, and the Aztecs/Mexica, who, from their central capital at Tenochtitlan, dominated much of the centre and south of the country (and the non-Aztec inhabitants of those areas) when Hernán Cortés first landed at Veracruz.

In contrast to what was the general rule in the rest of North America, the history of the colony of New Spain was one of racial intermingling (mestizaje). Mestizos, which in Mexico designate people who do not identify culturally with any Indigenous grouping, quickly came to account for a majority of the colony's population. Today, Mestizos in Mexico of mixed indigenous and European ancestry (with a minor African contribution) are still a majority of the population. Genetic studies vary over whether indigenous or European ancestry predominates in the Mexican Mestizo population.[216][217] In the 2015 census, 20.3% of the Mexican population self-identified as indigenous. In the 2020 INEGI (National Institute of Statistics and Geography) census showed that at the national level there are 11.8 million indigenous people (9.3% of the Mexican population). In 2020 the National Institute of Indigenous Peoples reported 11.1 million people in Mexico belonging to an indigenous ethnicity (8.8% of the Mexican population).[218] The indigenous population is distributed throughout the territory of Mexico, but is especially concentrated in the Sierra Madre del Sur, the Yucatán Peninsula and in the most remote and difficult-to-access areas, such as the Sierra Madre Oriental, the Sierra Madre Occidental and neighboring areas.[219] The CDI identifies 62 Indigenous groups in Mexico, each with a unique language.[220][221]

In the states of Chiapas and Oaxaca and in the interior of the Yucatán Peninsula a large amount of the population is Indigenous descent with the largest ethnic group being mayan with a population of 900,000.[222] Large Indigenous minorities, including Aztecs or Nahua, Purépechas, Mazahua, Otomi, and Mixtecs are also present in the central regions of Mexico. In the Northern and Bajio regions of Mexico, Indigenous people are a small minority.

The General Law of Linguistic Rights of the Indigenous Peoples grants all Indigenous languages spoken in Mexico, regardless of the number of speakers, the same validity as Spanish in all territories in which they are spoken, and Indigenous peoples are entitled to request some public services and documents in their native languages.[223] Along with Spanish, the law has granted them—more than 60 languages—the status of "national languages". The law includes all Indigenous languages of the Americas regardless of origin; that is, it includes the Indigenous languages of ethnic groups non-native to the territory. The National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples recognizes the language of the Kickapoo, who immigrated from the United States,[224] and recognizes the languages of the Indigenous refugees from Guatemala.[225] The Mexican government has promoted and established bilingual primary and secondary education in some Indigenous rural communities. Nonetheless, of the Indigenous peoples in Mexico, 93% are either a native speaker or a bilingual second language speaker of Spanish with only about 62.4% of them (or 5.4% of the country's population) speak an Indigenous language and about a sixth do not speak Spanish (0.7% of the country's population).[226]

The Indigenous peoples in Mexico have the right of free determination under the second article of the constitution. According to this article the Indigenous peoples are granted:[227]

- the right to decide the internal forms of social, economic, political and cultural organization;

- the right to apply their own normative systems of regulation as long as human rights and gender equality are respected;

- the right to preserve and enrich their languages and cultures;

- the right to elect representatives before the municipal council in which their territories are located;

amongst other rights.

United States

Indigenous peoples in what is now the contiguous United States, including their descendants, were commonly called American Indians, or simply Indians domestically and since the late 20th century the term Native American came into common use. In Alaska, Indigenous peoples belong to 11 cultures with 11 languages. These include the St. Lawrence Island Yupik, Iñupiat, Athabaskan, Yup'ik, Cup'ik, Unangax, Alutiiq, Eyak, Haida, Tsimshian, and Tlingit,[228] and are collectively called Alaska Natives. They include Native American peoples as well as Inuit, who are distinct but occupy areas of the region.

The United States has authority with Indigenous Polynesian peoples, which include Hawaiians, Marshallese (Micronesian), and Samoan; politically they are classified as Pacific Islander American. They are geographically, genetically, and culturally distinct from Indigenous peoples of the mainland continents of the Americas.

Native Americans in the United States make up 1.1% of the population.[229] In the 2020 census, 3.7 million people identified as Native American and Alaska Native alone. A total of 9.7 million people identified as Native Americans and Alaska Native, either alone or in combination with one or more ethnicity or other races.[6] Tribes have established their own criteria for membership, which are often based on blood quantum, lineal descent, or residency. A minority of Native Americans live in land units called Indian reservations.

Some California and Southwestern tribes, such as the Kumeyaay, Cocopa, Pascua Yaqui, Tohono O'odham and Apache, span both sides of the US–Mexican border. By treaty, Haudenosaunee people have the legal right to freely cross the US–Canada border. Athabascan, Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian, Iñupiat, Blackfeet, Nakota, Cree, Anishinaabe, Huron, Lenape, Mi'kmaq, Penobscot, and Haudenosaunee, among others, live in both Canada and the United States. The international border cut through their common cultural territory.

Belize

Mestizos (mixed European-Indigenous) number about 34% of the population; unmixed Maya make up another 10.6% (Kekchi, Mopan, and Yucatec). The Garifuna, who came to Belize in the 19th century from Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, have mixed African, Carib and Arawak ancestry and make up another 6% of the population.[230]

Costa Rica

There are over 114,000 inhabitants of Native American origins, representing 2.4% of the population. Most of them live in secluded reservations, distributed among eight ethnic groups: Quitirrisí (In the Central Valley), Matambú or Chorotega (Guanacaste), Maleku (Northern Alajuela), Bribri (Southern Atlantic), Cabécar (Cordillera de Talamanca), Boruca (Southern Costa Rica) and Ngäbe (Southern Costa Rica long the Panamá border).

These native groups are characterized for their work in wood, like masks, drums and other artistic figures, as well as fabrics made of cotton.

Their subsistence is based on agriculture, having corn, beans and plantains as the main crops.

El Salvador

Estimates for El Salvador's indigenous population vary. The last time a reported census had an Indigenous ethnic option was in 2007, which estimated that 0.23% of the population identified as Indigenous.[26] Historically, estimates have claimed higher amounts. A 1930 census stated that 5.6% were Indigenous.[231] By the mid-20th century, there may have been as much as 20% (or 400,000) that would qualify as "Indigenous". Another estimate stated that by the late 1980s, 10% of the population was Indigenous, and another 89% was mestizo (or people of mixed European and Indigenous ancestry).[232]

Much of El Salvador was home to the Pipil, the Lenca, Xinca, and Kakawira. The Pipil lived in western El Salvador, spoke Nawat, and had many settlements there, most noticeably Cuzcatlan. The Pipil had no precious mineral resources, but they did have rich and fertile land that was good for farming. The Spaniards were disappointed not to find gold or jewels in El Salvador as they had in other lands like Guatemala or Mexico, but upon learning of the fertile land in El Salvador, they attempted to conquer it. Noted Meso-American Indigenous warriors to rise militarily against the Spanish included Princes Atonal and Atlacatl of the Pipil people in central El Salvador and Princess Antu Silan Ulap of the Lenca people in eastern El Salvador, who saw the Spanish not as gods but as barbaric invaders. After fierce battles, the Pipil successfully fought off the Spanish army led by Pedro de Alvarado along with their Indigenous allies (the Tlaxcalas), sending them back to Guatemala. After many other attacks with an army reinforced with Indigenous allies, the Spanish were able to conquer Cuzcatlan. After further attacks, the Spanish also conquered the Lenca people. Eventually, the Spaniards intermarried with Pipil and Lenca women, resulting in the mestizo population that would make up the vast majority of the Salvadoran people. Today many Pipil and other Indigenous populations live in the many small towns of El Salvador like Izalco, Panchimalco, Sacacoyo, and Nahuizalco.

Guatemala

Guatemala has one of the largest Indigenous populations in Central America, with approximately 43.6% of the population considering themselves Indigenous.[233] The Indigenous demographic portion of Guatemala's population consists of majority Mayan groups and one Non-Mayan group. The Mayan language speaking portion makes up 29.7% of the population and is distribuied into 23 groups namely Q’eqchi' 8.3%, K’iche 7.8%, Mam 4.4%, Kaqchikel 3%, Q'anjob'al 1.2%, Poqomchi' 1%, and Other 4%.[233] The Non-Mayan group consists of the Xinca who are another set of Indigenous people making up 1.8% of the population.[233] Other sources indicate that between 50% and 60% of the population could be Indigenous, because part of the Mestizo population is predominantly Indigenous.

The Mayan tribes cover a vast geographic area throughout Central America and expanding beyond Guatemala into other countries. One could find vast groups of Mayan people in Boca Costa, in the Southern portions of Guatemala, as well as the Western Highlands living together in close communities.[234] Within these communities and outside of them, around 23 Indigenous languages (or Native American Indigenous languages) are spoken as a first language. Of these 23 languages, they only received official recognition by the Government in 2003 under the Law of National Languages.[233] The Law on National Languages recognizes 23 Indigenous languages including Xinca, enforcing that public and government institutions not only translate but also provide services in said languages.[235] It would provide services in Cakchiquel, Garifuna, Kekchi, Mam, Quiche and Xinca.[236]

.jpg.webp)

The Law of National Languages has been an effort to grant and protect Indigenous people rights not afforded to them previously. Along with the Law of National Languages passed in 2003, in 1996 the Guatemalan Constitutional Court had ratified the ILO Convention 169 on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples.[237] The ILO Convention 169 on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples, is also known as Convention 169. Which is the only International Law regarding Indigenous peoples that Independent countries can adopt. The convention, establishes that governments like Guatemala's must consult with Indigenous groups prior to any projects occurring on tribal lands.[238]

Honduras

About five percent of the population are of full-blooded Indigenous descent, but as much as 80 percent of Hondurans are mestizo or part-Indigenous with European admixture, and about ten percent are of Indigenous or African descent.[239] The largest concentrations of Indigenous communities in Honduras are in the westernmost areas facing Guatemala and along the coast of the Caribbean Sea, as well as on the border with Nicaragua.[239] The majority of Indigenous people are Lencas, Miskitos to the east, Mayans, Pech, Sumos, and Tolupan.[239]

Nicaragua

About 5% of the Nicaraguan population are Indigenous. The largest Indigenous group in Nicaragua is the Miskito people. Their territory extended from Cape Camarón, Honduras, to Rio Grande, Nicaragua along the Mosquito Coast. There is a native Miskito language, but large numbers speak Miskito Coast Creole, Spanish, Rama and other languages. Their use of Creole English came about through frequent contact with the British, who colonized the area. Many Miskitos are Christians. Traditional Miskito society was highly structured, politically and otherwise. It had a king, but he did not have total power. Instead, the power was split between himself, a Miskito Governor, a Miskito General, and by the 1750s, a Miskito Admiral. Historical information on Miskito kings is often obscured by the fact that many of the kings were semi-mythical.

Another major Indigenous culture in eastern Nicaragua are the Mayangna (or Sumu) people, counting some 10,000 people.[240] A smaller Indigenous culture in southeastern Nicaragua are the Rama.

Other Indigenous groups in Nicaragua are located in the central, northern, and Pacific areas and they are self-identified as follows: Chorotega, Cacaopera (or Matagalpa), Xiu-Subtiaba, and Nicarao.[241]

Panama

Indigenous peoples of Panama, or Native Panamanians, are the native peoples of Panama. According to the 2010 census, they make up 12.3% of the overall population of 3.4 million, or just over 418,000 people. The Ngäbe and Buglé comprise half of the indigenous peoples of Panama.[242]

Many of the Indigenous Peoples live on comarca indígenas,[243] which are administrative regions for areas with substantial Indigenous populations. Three comarcas (Comarca Emberá-Wounaan, Guna Yala, Ngäbe-Buglé) exist as equivalent to a province, with two smaller comarcas (Guna de Madugandí and Guna de Wargandí) subordinate to a province and considered equivalent to a corregimiento (municipality).Argentina

In 2005, Indigenous population living in Argentina (known as pueblos originarios) numbered about 600,329 (1.6% of total population); this figure includes 457,363 people who self-identified as belonging to an Indigenous ethnic group and 142,966 who identified themselves as first-generation descendants of an Indigenous people.[244] The ten most populous Indigenous peoples are the Mapuche (113,680 people), the Kolla (70,505), the Toba (69,452), the Guaraní (68,454), the Wichi (40,036), the Diaguita–Calchaquí (31,753), the Mocoví (15,837), the Huarpe (14,633), the Comechingón (10,863) and the Tehuelche (10,590). Minor but important peoples are the Quechua (6,739), the Charrúa (4,511), the Pilagá (4,465), the Chané (4,376), and the Chorote (2,613). The Selknam (Ona) people are now virtually extinct in its pure form. The languages of the Diaguita, Tehuelche, and Selknam nations have become extinct or virtually extinct: the Cacán language (spoken by Diaguitas) in the 18th century and the Selknam language in the 20th century; one Tehuelche language (Southern Tehuelche) is still spoken by a handful of elderly people.

Bolivia

In Bolivia, the 2001 census reported that 62% of residents over the age of 15 identify as belonging to an Indigenous people. Some 3.7% report growing up with an Indigenous mother tongue but do not identify as Indigenous.[245] When both of these categories are totaled, and children under 15, some 66.4% of Bolivia's population was recorded as Indigenous in the 2001 Census.[246]

The largest Indigenous ethnic groups are: Quechua, about 2.5 million people; Aymara, 2.0 million; Chiquitano, 181,000; Guaraní, 126,000; and Mojeño, 69,000. Some 124,000 belong to smaller Indigenous groups.[247] The Constitution of Bolivia, enacted in 2009, recognizes 36 cultures, each with its own language, as part of a pluri-national state. Some groups, including CONAMAQ (the National Council of Ayllus and Markas of Qullasuyu), draw ethnic boundaries within the Quechua- and Aymara-speaking population, resulting in a total of 50 Indigenous peoples native to Bolivia.

Large numbers of Bolivian highland peasants retained Indigenous language, culture, customs, and communal organization throughout the Spanish conquest and the post-independence period. They mobilized to resist various attempts at the dissolution of communal landholdings and used legal recognition of "empowered caciques" to further communal organization. Indigenous revolts took place frequently until 1953.[248] While the National Revolutionary Movement government begun in 1952 discouraged people identifying as Indigenous (reclassifying rural people as campesinos, or peasants), renewed ethnic and class militancy re-emerged in the Katarista movement beginning in the 1970s.[249] Many lowland Indigenous peoples, mostly in the east, entered national politics through the 1990 March for Territory and Dignity organized by the CIDOB confederation. That march successfully pressured the national government to sign the ILO Convention 169 and to begin the still-ongoing process of recognizing and giving official title to Indigenous territories. The 1994 Law of Popular Participation granted "grassroots territorial organizations;" these are recognized by the state and have certain rights to govern local areas.

Some radio and television programs are produced in the Quechua and Aymara languages. The constitutional reform in 1997 recognized Bolivia as a multi-lingual, pluri-ethnic society and introduced education reform. In 2005, for the first time in the country's history, an Indigenous Aymara, Evo Morales, was elected as president.

Morales began work on his "Indigenous autonomy" policy, which he launched in the eastern lowlands department on 3 August 2009. Bolivia was the first nation in the history of South America to affirm the right of Indigenous people to self-government.[250] Speaking in Santa Cruz Department, the President called it "a historic day for the peasant and Indigenous movement", saying that, though he might make errors, he would "never betray the fight started by our ancestors and the fight of the Bolivian people".[250] A vote on further autonomy for jurisdictions took place in December 2009, at the same time as general elections to office. The issue divided the country.[251]

At that time, Indigenous peoples voted overwhelmingly for more autonomy: five departments that had not already done so voted for it;[252][253] as did Gran Chaco Province in Taríja, for regional autonomy;[254] and 11 of 12 municipalities that had referendums on this issue.[252]

Brazil

Indigenous peoples of Brazil make up 0.4% of Brazil's population, or about 817,000 people, but millions of Brazilians are mestizo or have some Indigenous ancestry.[255] Indigenous peoples are found in the entire territory of Brazil, although in the 21st century, the majority of them live in Indigenous territories in the North and Center-Western part of the country. On 18 January 2007, Fundação Nacional do Índio (FUNAI) reported that it had confirmed the presence of 67 different uncontacted tribes in Brazil, up from 40 in 2005. Brazil is now the nation that has the largest number of uncontacted tribes, and the island of New Guinea is second.[255]

The Washington Post reported in 2007, "As has been proved in the past when uncontacted tribes are introduced to other populations and the microbes they carry, maladies as simple as the common cold can be deadly. In the 1970s, 185 members of the Panara tribe died within two years of discovery after contracting such diseases as flu and chickenpox, leaving only 69 survivors."[256]

Chile

According to the 2012 Census, 10% of the Chilean population, including the Rapa Nui (a Polynesian people) of Easter Island, was Indigenous, although most show varying degrees of mixed heritage.[257] Many are descendants of the Mapuche, and live in Santiago, Araucanía and Los Lagos Region. The Mapuche successfully fought off defeat in the first 300–350 years of Spanish rule during the Arauco War. Relations with the new Chilean Republic were good until the Chilean state decided to occupy their lands. During the Occupation of Araucanía the Mapuche surrendered to the country's army in the 1880s. Their land was opened to settlement by Chileans and Europeans. Conflict over Mapuche land rights continues to the present.

Other groups include the Aymara, the majority of whom live in Bolivia and Peru, with smaller numbers in the Arica-Parinacota and Tarapacá regions, and the Atacama people (Atacameños), who reside mainly in El Loa.

Colombia

A minority today within Colombia's overwhelmingly Mestizo and White Colombian population, Indigenous peoples living in Colombia, consist of around 85 distinct cultures and more than 1,378,884 people.[258][259] A variety of collective rights for Indigenous peoples are recognized in the 1991 Constitution.

One of the influences is the Muisca culture, a subset of the larger Chibcha ethnic group, famous for their use of gold, which led to the legend of El Dorado. At the time of the Spanish conquest, the Muisca were the largest Indigenous civilization geographically between the Incas and the Aztecs empires.

Ecuador

Ecuador was the site of many Indigenous cultures, and civilizations of different proportions. An early sedentary culture, known as the Valdivia culture, developed in the coastal region, while the Caras and the Quitus unified to form an elaborate civilization that ended at the birth of the Capital Quito. The Cañaris near Cuenca were the most advanced, and most feared by the Inca, due to their fierce resistance to the Incan expansion. Their architecture remains were later destroyed by Spaniards and the Incas.

Between 55% and 65% of Ecuador's population consists of Mestizos of mixed indigenous and European ancestry while indigenous people comprise about 25%.[260] Genetic analysis indicates that Ecuadorian Mestizos are of predominantly indigenous ancestry.[261] Approximately 96.4% of Ecuador's Indigenous population are Highland Quichuas living in the valleys of the Sierra region. Primarily consisting of the descendants of peoples conquered by the Incas, they are Kichwa speakers and include the Caranqui, the Otavalos, the Cayambe, the Quitu-Caras, the Panzaleo, the Chimbuelo, the Salasacan, the Tugua, the Puruhá, the Cañari, and the Saraguro. Linguistic evidence suggests that the Salascan and the Saraguro may have been the descendants of Bolivian ethnic groups transplanted to Ecuador as mitimaes.

Coastal groups, including the Awá, Chachi, and the Tsáchila, make up 0.24% percent of the Indigenous population, while the remaining 3.35 percent live in the Oriente and consist of the Oriente Kichwa (the Canelo and the Quijos), the Shuar, the Huaorani, the Siona-Secoya, the Cofán, and the Achuar.

In 1986, Indigenous peoples formed the first "truly" national political organization. The Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE) has been the primary political institution of Indigenous peoples since then and is now the second largest political party in the nation. It has been influential in national politics, contributing to the ouster of presidents Abdalá Bucaram in 1997 and Jamil Mahuad in 2000.

Peru

According to the 2017 Census, the Indigenous population in Peru make up around 26% approximately.[4] However, this does not include Mestizos of mixed indigenous and European descent, who make up the majority of the population. Genetic testing indicates that Peruvian Mestizos are of predominantly indigenous ancestry.[262] Indigenous traditions and customs have shaped the way Peruvians live and see themselves today. Cultural citizenship—or what Renato Rosaldo has called, "the right to be different and to belong, in a democratic, participatory sense" (1996:243)—is not yet very well developed in Peru. This is perhaps no more apparent than in the country's Amazonian regions where Indigenous societies continue to struggle against state-sponsored economic abuses, cultural discrimination, and pervasive violence.[263]

Venezuela

Most Venezuelans have some degree of indigenous heritage even if they may not identify as such. The 2011 census estimated that around 52% of the population identified as mestizo. But those who identify as Indigenous, from being raised in those cultures, make up only around 2% of the total population. The Indigenous peoples speak around 29 different languages and many more dialects. As some of the ethnic groups are very small, their native languages are in danger of becoming extinct in the next decades. The most important Indigenous groups are the Ye'kuana, the Wayuu, the Pemon and the Warao. The most advanced Indigenous peoples to have lived within the boundaries of present-day Venezuela is thought to have been the Timoto-cuicas, who lived in the Venezuelan Andes. Historians estimate that there were between 350 thousand and 500 thousand Indigenous inhabitants at the time of Spanish colonization. The most densely populated area was the Andean region (Timoto-cuicas), thanks to their advanced agricultural techniques and ability to produce a surplus of food.

The 1999 constitution of Venezuela gives indigenous peoples special rights, although the vast majority of them still live in very critical conditions of poverty. The government provides primary education in their languages in public schools to some of the largest groups, in efforts to continue the languages.

Other parts of the Americas

Indigenous peoples make up the majority of the population in Bolivia and Peru, and are a significant element in most other former Spanish colonies. Exceptions to this include Uruguay (Charrúa). According to the 2011 Census, 2.4% of Uruguayans reported having Indigenous ancestry.[194] Some governments recognize some of the major Indigenous languages as official languages: Quechua in Peru and Bolivia; Aymara also in Peru and Bolivia, Guaraní in Paraguay, and Greenlandic in Greenland.

Rise of Indigenous movements

| Part of a series on |

| Indigenous rights |

|---|

| Rights |

|

| Governmental organizations |

|

| NGOs and political groups |

|

| Issues |

|

| Legal representation |

|

| Category |

Since the late 20th century, Indigenous peoples in the Americas have become more politically active in asserting their treaty rights and expanding their influence. Some have organized in order to achieve some sort of self-determination and preservation of their cultures. Organizations such as the Coordinator of Indigenous Organizations of the Amazon River Basin and the Indian Council of South America are examples of movements that are overcoming national borders to reunite Indigenous populations, for instance those across the Amazon Basin. Similar movements for Indigenous rights can also be seen in Canada and the United States, with movements like the International Indian Treaty Council and the accession of native Indigenous groups into the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization.

There has been a recognition of Indigenous movements on an international scale. The membership of the United Nations voted to adopt the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, despite dissent from some of the stronger countries of the Americas.

In Colombia, various Indigenous groups have protested the denial of their rights. People organized a march in Cali in October 2008 to demand the government live up to promises to protect Indigenous lands, defend the Indigenous against violence, and reconsider the free trade pact with the United States.[264]

Indigenous heads of state

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

The first Indigenous candidate to be democratically elected as head of a country in the Americas was Benito Juárez, a Zapotec Mexican who was elected President of Mexico in 1858.[265]

In 1930 Luis Miguel Sánchez Cerro became the first Peruvian President with Indigenous Peruvian ancestry and the first in South America.[266] He came to power in a military coup.

In 2005, Evo Morales of the Aymara people was the first Indigenous candidate elected as president of Bolivia and the first elected in South America.[267]

Genetic research

Genetic history of Indigenous peoples of the Americas primarily focuses on Human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroups and Human mitochondrial DNA haplogroups. "Y-DNA" is passed solely along the patrilineal line, from father to son, while "mtDNA" is passed down the matrilineal line, from mother to offspring of both sexes. Neither recombines, and thus Y-DNA and mtDNA change only by chance mutation at each generation with no intermixture between parents' genetic material.[268] Autosomal "atDNA" markers are also used, but differ from mtDNA or Y-DNA in that they overlap significantly.[269] AtDNA is generally used to measure the average continent-of-ancestry genetic admixture in the entire human genome and related isolated populations.[269]

Genetic comparisons of the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) of some Native Americans to that of some Siberian and Central Asian peoples have led Russian researcher I.A. Zakharov to believe that, among all the previously studied Asian peoples, it is "the peoples living between Altai and Lake Baikal along the Sayan mountains that are genetically closest to" Indigenous Americans.[270]

Some scientific evidence links Indigenous peoples of the Americas to Asian peoples, specifically the Indigenous peoples of Siberia, such as the Ket, Selkup, Chukchi and Koryak peoples. Indigenous peoples of the Americas have been linked to some extent to North Asian populations by the distribution of blood types, and in genetic composition as reflected by molecular data, and limited DNA studies.[271][272][273]

The common occurrence of the mtDNA Haplogroups A, B, C, and D among eastern Asian and Native American populations has been noted.[274] Some subclades of C and D that have been found in the limited populations of Native Americans who have agreed to DNA testing[272][273] bear some resemblance to the C and D sublades in Mongolian, Amur, Japanese, Korean, and Ainu populations.[274][275]

Available genetic patterns lead to two main theories of genetic episodes affecting the Indigenous peoples of the Americas; first with the initial peopling of the Americas, and secondly with European colonization of the Americas.[276][277][278] The former is the determinant factor for the number of gene lineages, zygosity mutations, and founding haplotypes present in today's Indigenous peoples of the Americas populations.[277]

The most popular theory among anthropologists is the Bering Strait theory, of human settlement of the New World occurred in stages from the Bering sea coast line, with a possible initial layover of 10,000 to 20,000 years in Beringia for the small founding population.[279][280][281] The micro-satellite diversity and distributions of the Y lineage specific to South America indicates that certain Indigenous peoples of the Americas populations have been isolated since the initial colonization of the region.[282] The Na-Dené, Inuit and Indigenous populations of Alaska exhibit haplogroup Q (Y-DNA) mutations, however are distinct from other Indigenous peoples of the Americas with various mtDNA and atDNA mutations.[283][284][285] This suggests that the earliest migrants into the northern extremes of North America and Greenland derived from later migrant populations.[286][287]

A 2013 study in Nature reported that DNA found in the 24,000-year-old remains of a young boy from the archaeological Mal'ta-Buret' culture suggest that up to one-third of the ancestry of Indigenous peoples may be traced back to western Eurasians, who may have "had a more north-easterly distribution 24,000 years ago than commonly thought" (with the rest tracing back to early East Asian peoples).[288] "We estimate that 15 to 30 percent of Native American ancestry may originate through gene flow from this ancient population", the authors wrote. Professor Kelly Graf said:

"Our findings are significant at two levels. First, it shows that Upper Paleolithic Siberians came from a cosmopolitan population of early modern humans that spread out of Africa to Europe and Central and South Asia. Second, Paleoindian skeletons like Buhl Woman with phenotypic traits atypical of modern-day indigenous Americans can be explained as having a direct historical connection to Upper Paleolithic Siberia."

A route through Beringia is seen as more likely than the Solutrean hypothesis.[288] Kashani et al. 2012 state that "The similarities in ages and geographical distributions for C4c and the previously analyzed X2a lineage provide support to the scenario of a dual origin for Paleo-Indians. Taking into account that C4c is deeply rooted in the Asian portion of the mtDNA phylogeny and is indubitably of Asian origin, the finding that C4c and X2a are characterized by parallel genetic histories definitively dismisses the controversial hypothesis of an Atlantic glacial entry route into North America."[289]

Genetic analyses of HLA I and HLA II genes as well as HLA-A, -B, and -DRB1 gene frequencies links the Ainu people in northern Japan and southeastern Russia to some Indigenous peoples of the Americas, especially to populations on the Pacific Northwest Coast such as Tlingit. The scientists suggest that the main ancestor of the Ainu and of some Indigenous groups can be traced back to Paleolithic groups in Southern Siberia.[290]

A 2016 study found that Indigenous peoples of the Americas and Polynesians most likely came into contact around 1200.[291]

A study published in the Nature journal in 2018 concluded that Native Americans descended from a single founding population which initially split from East Asians at about ~36,000 BC, with geneflow between Ancestral Native Americans and Siberians persisting until ~25,000BC, before becoming isolated in the Americas at ~22,000BC. Northern and Southern Native American subpopulationes split from each other at ~17,500BC. There is also some evidence for a back-migration from the Americas into Siberia after ~11,500BC.[292]