Zelda Fitzgerald

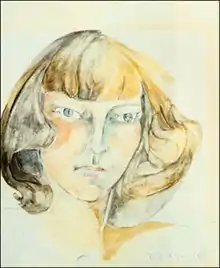

Zelda Fitzgerald (née Sayre; July 24, 1900 – March 10, 1948) was an American novelist, painter, and socialite.

Zelda Fitzgerald | |

|---|---|

Zelda Sayre, February 1920 | |

| Born | Zelda Sayre July 24, 1900 Montgomery, Alabama, U.S. |

| Died | March 10, 1948 (aged 47) Asheville, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

| Period | 1920–1948 |

| Spouse | |

| Children | Frances Scott Fitzgerald |

| Signature | |

| |

Born in Montgomery, Alabama, she was noted for her beauty and high spirits, and was dubbed by her husband F. Scott Fitzgerald as "the first American flapper". She and Scott became emblems of the Jazz Age, for which they are still celebrated.[1] The immediate success of Scott's first novel, This Side of Paradise (1920), brought them into contact with high society, but their marriage was plagued by wild drinking, infidelity and bitter recriminations. Ernest Hemingway, whom Fitzgerald disliked, blamed her for her husband's declining literary output. Zelda suffered from mental health crisis and was increasingly confined to specialist clinics.[2] Different accounts suggest that she suffered from schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or alternatively that she was victim of manipulation by her husband.[3] The couple were living apart when Scott died suddenly in 1940. Zelda Fitzgerald died over seven years later in a fire at the hospital in Asheville, North Carolina, in which she was a patient.

A 1970 biography by Nancy Milford was on the short list of contenders for the Pulitzer Prize. In 1992, Fitzgerald was inducted into the Alabama Women's Hall of Fame.

Early life and family background

Born in Montgomery, Alabama, Zelda Sayre was the youngest of six children. Her mother, Minerva Buckner "Minnie" Machen (November 23, 1860 – January 13, 1958), named her after characters in two little-known stories: Jane Howard's "Zelda: A Tale of the Massachusetts Colony" (1866) and Robert Edward Francillon's "Zelda's Fortune" (1874). A spoiled child, Fitzgerald was doted upon by her mother, but her father, Anthony Dickinson Sayre (1858–1931)[4]—a justice of the Supreme Court of Alabama and one of Alabama's leading jurists—was a strict and remote man. The family was descended from early settlers of Long Island, who had moved to Alabama before the Civil War. By the time of Zelda's birth, the Sayres were a prominent Southern family. Her great-uncle, John Tyler Morgan, served six terms in the United States Senate; her paternal grandfather edited a newspaper in Montgomery; and her maternal grandfather was Willis Benson Machen, who served a partial term as a U.S. senator from Kentucky.[5][6]

As a child, Fitzgerald was extremely active. She danced, took ballet lessons and enjoyed the outdoors.[7] In 1914, Fitzgerald began attending Sidney Lanier High School. She was bright, but uninterested in her lessons. Her work in ballet continued into high school, where she had an active social life. She drank, smoked and spent much of her time with boys, and she remained a leader in the local youth social scene.[7] A newspaper article about one of her dance performances quoted her as saying that she cared only about "boys and swimming".[8] She developed an appetite for attention, actively seeking to flout convention—whether by dancing or by wearing a tight, flesh-colored bathing suit to fuel rumors that she swam nude.[9] Her father's reputation was something of a safety net, preventing her social ruin,[10] but Southern women of the time were expected to be delicate, docile and accommodating. Consequently, Fitzgerald's antics were shocking to many of those around her, and she became—along with her childhood friend and future Hollywood starlet Tallulah Bankhead—a mainstay of Montgomery gossip.[11] Her ethos was encapsulated beneath her high-school graduation photo:

Why should all life be work, when we all can borrow? Let's think only of today, and not worry about tomorrow.[12]

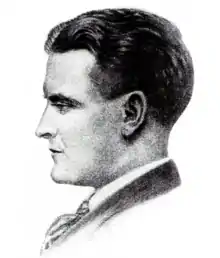

F. Scott Fitzgerald

Zelda Sayre first met the future novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald in July 1918, after he had volunteered for the army, and was stationed at Camp Sheridan, outside Montgomery. Scott began to call her daily, and came into Montgomery on his free days.[7] He talked of his plans to be famous, and sent her a chapter of a book he was writing. He was so taken with Zelda Sayre that he redrafted the character of Rosalind Connage in This Side of Paradise to resemble her.[7] He wrote, "all criticism of Rosalind ends in her beauty,"[13] and told Zelda that "the heroine does resemble you in more ways than four."[14] Zelda Sayre was more than a mere muse, however. At the conclusion of This Side of Paradise, the soliloquy of the protagonist Amory Blaine in the cemetery, for example, is taken directly from one of Zelda Sayre's letters to Fitzgerald.[15] Gloria Patch, in The Beautiful and Damned, is also known to be a permutation of the "subjects of statement" that appear in Zelda's letters.[16]

F. Scott Fitzgerald was known to appreciate and take from Zelda Sayre's letters, even plagiarising her diary while he was writing This Side of Paradise. In 1918, Scott showed her diary to his friend Peevie Parrot who then shared it with George Jean Nathan. There was allegedly discussion between the men of publishing it under the name of "The Diary of a Popular Girl".[17] Zelda Sayre's letters stand out for their "spontaneous turn of phrase and lyrical style" and tendency to use dashes, visually similar to the poems by Emily Dickinson, and experimental grammar.[18]

According to Nancy Milford, Scott and Zelda Sayre's first encounter was at a country club dance in Montgomery,[7] which Scott fictionalised in his novel The Great Gatsby, when he describes Jay Gatsby's first encounter with Daisy Buchanan, although he transposed the location in the novel to a train station.[19] Scott was not the only man courting Zelda Sayre, and the competition only drove Scott to want her more. In the ledger that he meticulously maintained throughout his life, Scott noted in 1918, on September 7, that he had fallen in love. Ultimately, she would do the same. Her biographer Nancy Milford wrote, "Scott had appealed to something in Zelda which no one before him had perceived: a romantic sense of self-importance which was kindred to his own."[20]

Their courtship was briefly interrupted in October when he was summoned north. He expected to be sent to France, but was instead assigned to Camp Mills, Long Island. While he was there, the Armistice with Germany was signed. He then returned to the base near Montgomery, and by December they were inseparable. Scott would later describe their behavior as "sexual recklessness."[21] On February 14, 1919, he was discharged from the military and went north to establish himself in New York City.[22]

They wrote frequently, and by March 1920, Scott had sent Zelda his mother's ring, and the two had become engaged.[23] Many of Zelda's friends and members of her family were wary of the relationship,[24] as they did not approve of Scott's excessive drinking, and Zelda's Episcopalian family did not like the fact that he was a Catholic.[24]

Marriage

By September, Scott had completed his first novel, This Side of Paradise, and the manuscript was quickly accepted for publication. When he heard the novel had been accepted, Scott wrote to his editor Maxwell Perkins, urging an accelerated release: "I have so many things dependent on its success—including of course a girl."[25] In November, he returned to Montgomery, triumphant with the news of his novel. Zelda agreed to marry him once the book was published;[26] he, in turn, promised to bring her to New York with "all the iridescence of the beginning of the world."[27] This Side of Paradise was published on March 26, Zelda arrived in New York on March 30, and on April 3, 1920, before a small wedding party in St. Patrick's Cathedral, they married.[28] According to Canterbery and Birch (and Fitzgerald himself), this first novel was Fitzgerald's "ace in the hole", a poker term. Scott saw the novel's publication as the way to Zelda's heart.[29]

Scott and Zelda quickly became celebrities of New York, as much for their wild behavior as for the success of This Side of Paradise. They were ordered to leave both the Biltmore Hotel and the Commodore Hotel for their drunkenness.[30] Zelda once jumped into the fountain at Union Square. When Dorothy Parker first met them, Zelda and Scott were sitting atop a taxi. Parker said, "They did both look as though they had just stepped out of the sun; their youth was striking. Everyone wanted to meet him."[31] Their social life was fueled with alcohol. Publicly, this meant little more than napping when they arrived at parties, but privately it increasingly led to bitter fights.[32] To their delight, in the pages of the New York newspapers Zelda and Scott had become icons of youth and success—enfants terribles of the Jazz Age.[33]

On Valentine's Day in 1921, while Scott was working to finish his second novel, The Beautiful and Damned, Zelda discovered she was pregnant. They decided to go to Scott's home in Saint Paul, Minnesota, to have the baby.[34] On October 26, 1921, she gave birth to Frances "Scottie" Fitzgerald. As she emerged from the anesthesia, Scott recorded Zelda saying, "Oh, God, goofo I'm drunk. Mark Twain. Isn't she smart—she has the hiccups. I hope it's beautiful and a fool—a beautiful little fool." Many of her words found their way into Scott's novels: in The Great Gatsby, the character Daisy Buchanan expresses a similar hope for her daughter.[35]

Zelda never became particularly domestic, nor showed any interest in housekeeping.[36] By 1922, the Fitzgeralds had employed a nurse for their daughter, a couple to clean their house, and a laundress.[37] When Harper & Brothers asked her to contribute to Favorite Recipes of Famous Women she wrote, "See if there is any bacon, and if there is, ask the cook which pan to fry it in. Then ask if there are any eggs, and if so try and persuade the cook to poach two of them. It is better not to attempt toast, as it burns very easily. Also, in the case of bacon, do not turn the fire too high, or you will have to get out of the house for a week. Serve preferably on china plates, though gold or wood will do if handy."[38]

In early 1922, Zelda again became pregnant. Although some writers have said that Scott's diaries include an entry referring to "Zelda and her abortionist", there is, in fact, no such entry. Zelda's thoughts on the second pregnancy are unknown, but in the first draft of The Beautiful and Damned, the novel Scott was completing, he wrote a scene in which the main female character Gloria believes she is pregnant and Anthony suggests she "talk to some woman and find out what's best to be done. Most of them fix it some way." Anthony's suggestion was removed from the final version, a change which shifted focus from the choice about abortion to Gloria's concern that a baby would ruin her figure.[39]

As The Beautiful and Damned neared publication, Burton Rascoe, the freshly appointed literary editor of the New York Tribune, approached Zelda for an opportunity to entice readers with a cheeky review of Scott's latest work. In her review, she made joking reference to the use of her diaries in Scott's work, but the lifted material became a genuine source of resentment:[40]

To begin with, every one must buy this book for the following aesthetic reasons: First, because I know where there is the cutest cloth of gold dress for only $300 in a store on Forty-second Street, and, also, if enough people buy it where there is a platinum ring with a complete circlet, and, also, if loads of people buy it my husband needs a new winter overcoat, although the one he has done well enough for the last three years ... It seems to me that on one page I recognized a portion of an old diary of mine which mysteriously disappeared shortly after my marriage, and, also, scraps of letters which, though considerably edited, sound to me vaguely familiar. In fact, Mr. Fitzgerald—I believe that is how he spells his name—seems to believe that plagiarism begins at home.[41]

The piece led to Zelda receiving offers from other magazines. In June 1922, a piece by Zelda Fitzgerald, "Eulogy on the Flapper", was published in Metropolitan Magazine. Though ostensibly a piece about the decline of the flapper lifestyle, Zelda's biographer Nancy Milford wrote that the essay was "a defense of her own code of existence."[42] Zelda described the flapper:

The Flapper awoke from her lethargy of sub-deb-ism, bobbed her hair, put on her choicest pair of earrings and a great deal of audacity and rouge and went into the battle. She flirted because it was fun to flirt and wore a one-piece bathing suit because she had a good figure ... she was conscious that the things she did were the things she had always wanted to do. Mothers disapproved of their sons taking the Flapper to dances, to teas, to swim and most of all to heart.[43]

Zelda continued writing, selling several short stories and articles. She helped Scott write the play The Vegetable, but when it flopped the Fitzgeralds found themselves in debt. Scott wrote short stories furiously to pay the bills, but became burned out and depressed.[44] In April 1924, they left for Paris.[45][46]

Expatriation

.jpg.webp)

After arriving in Paris, they soon relocated to Antibes[47] on the French Riviera. While Scott was absorbed writing The Great Gatsby, Zelda became infatuated with a dashing young French pilot, Edouard S. Jozan.[48] She spent afternoons swimming at the beach and evenings dancing at the casinos with Jozan. After six weeks, Zelda asked for a divorce. Scott at first demanded to confront Jozan, but instead dealt with Zelda's demand by locking her in their house, until she abandoned her request for divorce. Jozan did not know that she had asked for a divorce. He left the Riviera later that year, and the Fitzgeralds never saw him again. Later in life he told Zelda's biographer Milford that any infidelity had been imaginary: "They both had a need of drama, they made it up and perhaps they were the victims of their own unsettled and a little unhealthy imagination."[49] In Fitzgerald's, "A Life in Letters," Fitzgerald referred to Zelda's affair with Jozan in his August letter to Ludlow Fowler. He writes of lost illusions in The Great Gatsby as his lost certainty in Zelda's fidelity. The book reflected the dramatized pivotal aspects of his and Zelda's love, of courtship, break, restoration with financial success, and the Jozan betrayal: "I feel old too, this summer ... the whole burden of this novel—the loss of those illusions that give such color to the world that you don't care whether things are true or false as long as they partake of the magical glory." The Great Gatsby was in draft form during the July 1924 Jozan crisis; the typescript was sent to Scribners at the end of October.[50] Fitzgerald wrote in his notebooks, "That September 1924, I knew something had happened that could never be repaired."[51]

After the fight, the Fitzgeralds kept up appearances with their friends, seeming happy. In September, Zelda overdosed on sleeping pills. The couple never spoke of the incident, and refused to discuss whether it was a suicide attempt. Scott returned to writing, finishing The Great Gatsby in October. They attempted to celebrate with travel to Rome and Capri, but both were unhappy and unhealthy. When he received the proofs from his novel he fretted over the title: Trimalchio in West Egg, just Trimalchio or Gatsby, Gold-hatted Gatsby, or The High-bouncing Lover. It was Zelda who preferred The Great Gatsby.[52] It was also on this trip, while ill with colitis, that Zelda began painting.[53]

In April 1925, back in Paris, Scott met Ernest Hemingway, whose career he did much to promote. Hemingway and Scott Fitzgerald became firm friends, but Zelda and Hemingway disliked each other from their first meeting, and she openly described him as "bogus,"[54] "that fairy with hair on his chest" and "phoney as a rubber check."[55] She considered Hemingway's domineering macho persona to be merely a posture; Hemingway in turn, told Scott that Zelda was crazy.[54][56] Her dislike was probably not helped by Scott's repeated insistence that she recount the story of her affair with Jozan to Hemingway and his wife, Hadley. In an embellishment, the Fitzgeralds told the Hemingways that the affair ended when Jozan committed suicide.[57] It was through Hemingway, however, that the Fitzgeralds were introduced to much of the Lost Generation expatriate community: Gertrude Stein, Alice B. Toklas, Robert McAlmon, and others.[48]

One of the most serious rifts occurred when Zelda suspected that Scott was having a homosexual affair with Hemingway and publicly belittled him with homophobic slurs.[58] There is no evidence that either was homosexual, but Scott nonetheless decided to have sex with a prostitute to prove his heterosexuality. Zelda found condoms that he had purchased before any encounter occurred, and a bitter fight ensued, resulting in lingering jealousy.[59] She later threw herself down a flight of marble stairs at a party because Scott, engrossed in talking to Isadora Duncan, was ignoring her.[60]

Literary critic Edmund Wilson, recalling a party at the Fitzgerald home in Edgemoor, Delaware, in February 1928, described Zelda as follows:

I sat next to Zelda, who was at her iridescent best. Some of Scott's friends were irritated; others were enchanted, by her. I was one of the ones who were charmed. She had the waywardness of a Southern belle and the lack of inhibitions of a child. She talked with so spontaneous a color and wit—almost exactly in the way she wrote—that I very soon ceased to be troubled by the fact that the conversation was in the nature of a 'free association' of ideas and one could never follow up anything. I have rarely known a woman who expressed herself so delightfully and so freshly: she had no ready-made phrases on the one hand and made no straining for effect on the other. It evaporated easily, however, and I remember only one thing she said that night: that the writing of Galsworthy was a shade of blue for which she did not care.[61]

Obsession and illness

.jpg.webp)

Though Scott drew heavily upon his wife's intense personality in his writings, much of the conflict between them stemmed from the boredom and isolation Zelda experienced when Scott was writing. She would often interrupt him when he was working, and the two grew increasingly miserable throughout the 1920s. Scott had become severely alcoholic, Zelda's behavior became increasingly erratic, and neither made any progress on their creative endeavors.[62]

Fitzgerald had a deep desire to develop a talent that was entirely her own. At the age of 27, she became obsessed with ballet, which she had studied as a girl. She had been praised for her dancing skills as a child, and although the opinions of their friends vary as to her skill, it appears that she did have a fair degree of talent. But Scott was totally dismissive of his wife's desire to become a professional dancer, considering it a waste of time.[63]

She rekindled her studies too late in life to become a truly exceptional dancer, but she insisted on grueling daily practice (up to eight hours a day)[64] that contributed to her subsequent physical and mental exhaustion.[65] In September 1929, she was invited to join the ballet school of the San Carlo Opera Ballet Company in Naples, but, as close as this was to the success she desired, she declined the invitation.[66] While the public still believed the Fitzgeralds to live a life of glamor, friends noted that the couple's partying had somewhere gone from fashionable to self-destructive—both had become unpleasant company.[67]

In April 1930, Fitzgerald was admitted to a sanatorium in France where, after months of observation and treatment and a consultation with one of Europe's leading psychiatrists, Doctor Eugen Bleuler,[68] she was diagnosed as a schizophrenic.[69] In later years, Zelda is considered to have had bipolar disorder.[2][70][71] Initially admitted to a hospital outside Paris, she was later moved to a clinic in Montreux, Switzerland. The clinic primarily treated gastrointestinal ailments, and because of her profound psychological problems she was moved to a psychiatric facility in Prangins on the shores of Lake Geneva. She was released in September 1931, and the Fitzgeralds returned to Montgomery, Alabama, where her father, Judge Sayre, was dying. Amid her family's bereavement, Scott announced that he was leaving for Hollywood.[72] Zelda's father died while Scott was gone, her health again deteriorated and she had another breakdown. By February 1932, she had returned to living in a psychiatric clinic.[73]

Save Me the Waltz

In 1932, while being treated at the Phipps Clinic at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Zelda had a burst of creativity. Over the course of her first six weeks at the clinic, she wrote an entire novel and sent it to Scott's publisher, Maxwell Perkins.[74][75]

When Scott finally read Zelda's book, a week after she'd sent it to Perkins, he was furious. The book was a semi-autobiographical account of the Fitzgeralds' marriage. In letters, Scott berated her and fumed that the novel had drawn upon the autobiographical material that he planned to use in Tender Is the Night, which he'd been working on for years, and which would finally see publication in 1934.[76]

Scott forced Zelda to revise the novel, removing the parts that drew on shared material he wished to use. Scribner agreed to publish her book, and a printing of 3,010 copies was released on October 7, 1932.[77]

The parallels to the Fitzgeralds were obvious. The protagonist of the novel is Alabama Beggs (like Zelda, the daughter of a Southern judge), who marries David Knight, an aspiring painter who abruptly becomes famous for his work. They live the fast life in Connecticut before departing to live in France. Dissatisfied with her marriage, Alabama throws herself into ballet. Though told she has no chance, she perseveres and after three years becomes the lead dancer in an opera company. Alabama becomes ill from exhaustion, however, and the novel ends when they return to her family in the South, as her father is dying.[78]

Thematically, the novel portrays Alabama's struggle (and hence Zelda's as well) to rise above being "a back-seat driver about life" and to earn respect for her own accomplishments—to establish herself independently of her husband.[79] Zelda's writing style was quite different from Scott's. The language used in Save Me the Waltz is filled with verbal flourishes and complex metaphors. The novel is also deeply sensual; as literary scholar Jacqueline Tavernier-Courbin wrote in 1979, "The sensuality arises from Alabama's awareness of the life surge within her, the consciousness of the body, the natural imagery through which not only emotions but simple facts are expressed, the overwhelming presence of the senses, in particular touch and smell, in every description."[80]

In its time, the book was not well received by critics. To Zelda's dismay, it sold only 1,392 copies, for which she earned $120.73.[81] The failure of Save Me the Waltz, and Scott's scathing criticism of her for having written it—he called her "plagiaristic"[82] and a "third-rate writer"[82]—crushed her spirits. It was the only novel she ever saw published.

Remaining years, fire, and death

From the mid-1930s, Zelda spent the rest of her life in various stages of mental distress. Some of the paintings that she had created over the previous years, in and out of sanatoriums, were exhibited in 1934. As with the tepid reception of her book, Zelda was disappointed by the response to her art. The New Yorker described them merely as "Paintings by the almost mythical Zelda Fitzgerald; with whatever emotional overtones or associations may remain from the so-called Jazz Age." No actual description of the paintings was provided in the review.[83] She became violent and reclusive—in 1936 Scott placed her in the Highland Hospital in Asheville, North Carolina, writing ruefully to friends:[84]

Zelda now claims to be in direct contact with Christ, William the Conqueror, Mary Stuart, Apollo and all the stock paraphernalia of insane-asylum jokes ... For what she has really suffered, there is never a sober night that I do not pay a stark tribute of an hour to in the darkness. In an odd way, perhaps incredible to you, she was always my child (it was not reciprocal as it often is in marriages) ... I was her great reality, often the only liaison agent who could make the world tangible to her.[84]

Zelda remained in the hospital while Scott returned to Hollywood for a $1,000-a-week job with MGM in June 1937.[85] Without Zelda's knowledge, he began a serious affair with the movie columnist Sheilah Graham.[86] Despite the excitement of the affair, Scott was bitter and burned out. When their daughter Scottie was thrown out of her boarding school in 1938, he blamed Zelda. Though Scottie was subsequently accepted by Vassar College, his resentment of Zelda was stronger than ever before. Of Scott's mindset, Milford wrote, "The vehemence of his rancor toward Zelda was clear. It was she who had ruined him; she who had made him exhaust his talents ... He had been cheated of his dream by Zelda."[87]

After a drunken and violent fight with Graham in 1938, Scott returned to Asheville. A group from Zelda's hospital had planned to go to Cuba, but Zelda had missed the trip. The Fitzgeralds decided to go on their own. The trip was a disaster: Scott was beaten up when he tried to stop a cockfight and returned to the United States so intoxicated and exhausted that he was hospitalized.[88] The Fitzgeralds never saw each other again.[89]

Scott returned to Hollywood and Graham; Zelda returned to the hospital. She nonetheless made progress in Asheville, and in March 1940, four years after admittance, she was released.[90] She was nearing forty now, her friends were long gone, and the Fitzgeralds no longer had much money. Scott was increasingly embittered by his own failures and his old friend Hemingway's continued success. They wrote to each other frequently until Scott's death at 44 in December 1940. Zelda was unable to attend his funeral in Rockville, Maryland.[91]

Zelda read the unfinished manuscript of the novel Scott was writing upon his death, The Last Tycoon. She wrote to literary critic Edmund Wilson, who had agreed to edit the book, musing on his legacy. Zelda believed, her biographer Milford said, that Scott's work contained "an American temperament grounded in belief in oneself and 'will-to-survive' that Scott's contemporaries had relinquished. Scott, she insisted, had not. His work possessed a vitality and stamina because of his indefatigable faith in himself."[92]

After reading The Last Tycoon, Zelda began working on a new novel of her own, Caesar's Things. As she had missed Scott's funeral, so she missed Scottie's wedding. By August 1943 she had returned to the Highland Hospital. She worked on her novel while checking in and out of the hospital. She did not get better, nor did she finish the novel. On the night of March 10, 1948, a fire broke out in the hospital kitchen. Zelda was locked into a room, awaiting electroshock therapy. The fire moved through the dumbwaiter shaft, spreading onto every floor. The fire escapes were wooden, and they caught fire as well. Nine women, including Zelda, died.[93] She was identified by her dental records and, according to other reports, one of her slippers.[94]

Their daughter, Scottie, wrote after their deaths:

I think (short of documentary evidence to the contrary) that if people are not crazy, they get themselves out of crazy situations, so I have never been able to buy the notion that it was my father's drinking which led her to the sanitarium. Nor do I think she led him to the drinking.[95]

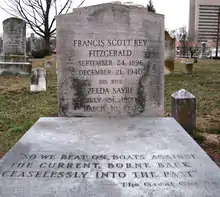

Scott and Zelda were buried in Rockville, Maryland — originally in the Rockville Union Cemetery, away from his family plot. Only one photograph of the original gravesite is known to exist, taken in 1970 by Fitzgerald scholar Richard Anderson and first published in 2016. At Scottie's request, her parents were later interred with the other Fitzgeralds at Saint Mary's Catholic Cemetery. Inscribed on their tombstone is the final sentence of The Great Gatsby: "So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past."[96]

Legacy

At the time of his sudden death in 1940, Scott believed himself a failure, and Zelda's death in 1948 was little noted. However, interest in the Fitzgeralds surged in the years following their deaths. In 1950, screenwriter Budd Schulberg, who knew the couple from his Hollywood years, wrote The Disenchanted, with characters based recognizably on the Fitzgeralds who end up as forgotten former celebrities, he awash with alcohol and she befuddled by mental illness. It was followed in 1951 by Cornell University professor Arthur Mizener's The Far Side of Paradise, a biography of F. Scott Fitzgerald that rekindled interest in the couple among scholars. Mizener's biography was serialized in The Atlantic Monthly, and a story about the book appeared in Life magazine, then one of America's most widely read and discussed periodicals. Scott was viewed as a fascinating failure; Zelda's mental health was largely blamed for his lost potential.[97]

A play based on The Disenchanted opened on Broadway in 1958. Also that year, Scott's Hollywood mistress Sheilah Graham published a memoir, Beloved Infidel, about his last years. Beloved Infidel became a bestseller and later a film starring Gregory Peck as Scott and Deborah Kerr as Graham. The book and movie painted him in a more sympathetic light than the earlier works. In 1970, however, the history of Scott and Zelda's marriage saw its most profound revision in a book by Nancy Milford, then a graduate student at Columbia University. Zelda: A Biography, the first book-length treatment of Zelda's life, became a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award, and figured for weeks on The New York Times best-seller list. The book recast Zelda as an artist in her own right whose talents were belittled by a controlling husband. Thus in the 1970s, Zelda became an icon of the feminist movement—a woman whose unappreciated potential had been suppressed by patriarchal society.[98] When Tennessee Williams dramatized the Fitzgeralds' lives in the 1980s in Clothes for a Summer Hotel, he drew heavily on Milford's account. A caricature of Scott and Zelda emerged: as epitomes of the Jazz Age's glorification of youth, as representatives of the Lost Generation, and as a parable about the pitfalls of too much success.[98]

Zelda was the inspiration for "Witchy Woman",[99][100] the song of seductive enchantresses written by Don Henley and Bernie Leadon for the Eagles, after Henley read Zelda's biography; of the muse, the partial genius behind her husband F. Scott Fitzgerald, the wild, bewitching, mesmerizing, quintessential "flapper" of the Jazz Age and the Roaring Twenties, embodied in The Great Gatsby as the uninhibited and reckless personality of Daisy Buchanan.[101]

Zelda's name served as inspiration for Princess Zelda, the eponymous character of The Legend of Zelda series of video games. Series co-creator Shigeru Miyamoto explained, "[Fitzgerald] was a famous and beautiful woman from all accounts, and I liked the sound of her name. So I took the liberty of using her name for the very first Zelda title."[102] New York City's borough of Manhattan's Battery Park's resident wild turkey Zelda (d. 2014)[103] was also named after her, because according to legend during one of Fitzgerald's nervous breakdowns, she went missing and was found in Battery Park, apparently having walked several miles downtown.[104] Of Zelda's legacy in popular culture, biographer Cline wrote, "Recently myth has likened Zelda to those other twentieth-century icons, Marilyn Monroe and Princess Diana. With each she shares a defiance of convention, intense vulnerability, doomed beauty, unceasing struggle for a serious identity, short tragic life and quite impossible nature."[105] In 1989, the F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald museum opened in Montgomery, Alabama. The museum is in a house they briefly rented in 1931 and 1932. It is one of the few places where some of Zelda's paintings are kept on display.[106]

Painting Zelda Fitzgerald as an artist in her own right, Deborah Pike wrote a biography titled The Subversive Art of Zelda Fitzgerald (2017). Pike notes Zelda's creative output as "an important contribution to the history of women's art with new perspectives on women and modernity, plagiarism, creative partnership, and the nature of mental illness," based on literary analysis of Zelda's published and unpublished work as well as her husband's.[16]

Critical reappraisal

After the success of Milford's 1970 biography, scholars and critics began to look at Zelda's work in a new light. In a 1968 edition of Save Me the Waltz, F. Scott Fitzgerald scholar Matthew Bruccoli had written, "Save Me the Waltz is worth reading partly because anything that illuminates the career of F. Scott Fitzgerald is worth reading—and because it is the only published novel of a brave and talented woman who is remembered for her defeats."[107] But as Save Me the Waltz was increasingly read alongside Milford's biography, a new perspective emerged.[108] In 1979, scholar Jacqueline Tavernier-Courbin wrote rebutting Bruccoli's position: "Save Me the Waltz is a moving and fascinating novel which should be read on its own terms equally as much as Tender Is the Night. It needs no other justification than its comparative excellence."[109] Save Me the Waltz became the focus of many literary studies that explored different aspects of her work: how the novel contrasted with Scott's take on the marriage in Tender Is the Night;[110] how the commodity culture that emerged in the 1920s placed stress on modern women;[108] and how these attitudes led to a misrepresentation of "mental illness" in women.[111]

Zelda's collected writings (including Save Me the Waltz), edited by Matthew J. Bruccoli, were published in 1991. New York Times literary critic Michiko Kakutani wrote, "That the novel was written in two months is amazing. That for all its flaws it still manages to charm, amuse and move the reader is even more remarkable. Zelda Fitzgerald succeeded, in this novel, in conveying her own heroic desperation to succeed at something of her own, and she also managed to distinguish herself as a writer with, as Edmund Wilson once said of her husband, a 'gift for turning language into something iridescent and surprising.'"[112]

Scholars continue to examine and debate the role that Scott and Zelda may have had in stifling each other's creativity.[113] Zelda's biographer Cline wrote that the two camps are "as diametrically opposed as the Plath and Hughes literary camps"—a reference to the heated controversy about the relationship of husband–wife poets Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath.[114]

Zelda's artwork also has been reappraised as interesting in its own right. After spending much of the 1950s and '60s in family attics—Zelda's mother even had much of the art burned because she disliked it[115]—her work has drawn the interest of scholars. Exhibitions of her work have toured the United States and Europe. A review of the exhibition by curator Everl Adair noted the influence of Vincent van Gogh and Georgia O'Keeffe on her paintings and concluded that her surviving corpus of art "represents the work of a talented, visionary woman who rose above tremendous odds to create a fascinating body of work—one that inspires us to celebrate the life that might have been."[115]

In 1992, Zelda was inducted into the Alabama Women's Hall of Fame.[116]

Notes

- Yaeger, Lynn (July 24, 2015). "Happy Birthday, Zelda Fitzgerald!". VOGUE. Retrieved August 7, 2022.

- Stamberg, Susan (September 3, 2013). "For F. Scott And Zelda Fitzgerald, A Dark Chapter In Asheville, N.C." NPR. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- Talley, Heather Laine (May 20, 2013). "Zelda Wasn't 'Crazy': How What You Don't Know About Fitzgerald Tells Us Something About 'Crazy' Women, Then and Now". HuffPost. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- Sayre, Anthony Dickinson (April 29, 1858 – November 17, 1931), Cline 2003, p. 27

- Milford 1970, pp. 1–7

- Bruccoli 2002, p. 89

- Milford 1970

- Milford 1970, p. 16

- Cline 2003, pp. 37–38

- Milford 1970, pp. 9–13

- Cline 2003, pp. 23–24

- Cline 2003, p. 38

- Cline 2003, p. 45

- Milford 1970, p. 32

- Cline 2003, p. 65

- Pike 2017, p. 39

- Pike 2017, p. 56

- Pike 2017, p. 43

- Bruccoli 2002

- Milford 1970, p. 33

- Milford 1970, p. 35; Bruccoli 2002, p. 89

- Milford 1970, pp. 35–36

- Milford 1970, p. 42

- Milford 1970, p. 43

- Milford 1970, p. 54

- Bruccoli 2002, p. 109

- Milford 1970, p. 57

- Milford 1970, p. 62; Cline 2003, p. 75; Bruccoli 2002, p. 128

- Canterbery & Birch 2006, p. 76

- Cline 2003, p. 87

- Milford 1970, p. 67

- Bruccoli 2002, pp. 131–32

- Milford 1970, p. 69; Cline 2003, p. 81; Bruccoli 2002, p. 131; Bryer, Jackson R. "A Brief Biography." In Curnutt 2004, p. 31

- Cline 2003, p. 109; Bryer in Curnutt 2004, p. 32

- Milford 1970, p. 84; Cline 2003, p. 116

- Bruccoli 2002, p. 139

- Milford 1970, p. 95

- Lanahan, Dorothy. "Introduction." In Bryer & Barks 2002, p. xxvii

- Milford 1970, p. 88; Cline 2003, pp. 125–26

- Milford 1970, p. 89

- Lanahan. In Bryer & Barks 2002, pp. xxvii–viii

- Milford 1970, p. 92

- Milford 1970, p. 91

- Bruccoli 2002, p. 185

- Milford 1970, p. 103

- Cline 2003, p. 130

- Fitzgerald 2003, p. 272

- Bruccoli 2002, p. 195

- Milford 1970, pp. 108–112

- Bruccoli 2002, p. xxvi

- Mizener 1951, p. 93

- Milford 1970, pp. 112–13; Bruccoli 2002, pp. 206–07

- Milford 1970, p. 113

- Milford 1970, p. 116

- Milford 1970, p. 122

- Bruccoli 2002, p. 226

- Milford 1970, p. 114

- Milford 1970, p. 183.

- Bruccoli 2002, p. 275

- Milford 1970, p. 117

- Wilson 2007, p. 311

- Milford 1970, p. 135

- Milford 1970, pp. 147–50

- Milford 1970, p. 141

- Milford 1970, p. 157

- Milford 1970, p. 156

- Milford 1970, p. 152

- Ludwig 1995, p. 181

- Milford 1970, p. 161

- Kramer, Peter D. (December 1, 1996). "How Crazy Was Zelda?". The New York Times. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- Conroy, Richard C. (April 8, 2016). "The Fitzgerald Museum". Princeton Alumni Weekly. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- Milford 1970, p. 193

- Milford 1970, p. 209

- Cline 2003, p. 304

- Milford 1970, pp. 209–12

- Milford 1970, pp. 220–25; Bryer in Curnutt 2004, p. 39.

- Cline 2003, p. 320

- Tavernier-Courbin 1979, pp. 31–33

- Tavernier-Courbin 1979, p. 36

- Tavernier-Courbin 1979, p. 40

- Milford 1970, p. 264

- Cline 2003, p. 325

- Milford 1970, p. 290

- Milford 1970, p. 308

- Milford 1970, p. 313

- Milford 1970, pp. 311–313

- Milford 1970, p. 323

- Milford 1970, p. 327

- Milford 1970, p. 329; Bryer in Curnutt 2004, p. 43.

- Milford 1970, p. 337

- Milford 1970, p. 350

- Milford 1970, p. 353

- Milford 1970, pp. 382–383

- Young 1979

- Lanahan. In Bryer & Barks 2002, p. xxix

- Mangum 2016

- Prigozy, Ruth. "Introduction: Scott, Zelda, and the culture of Celebrity." In Prigozy 2002, pp. 15–18

- Prigozy in Prigozy 2002, pp. 18–21

- Crowe, Cameron (August 2003), "Conversations with Don Henley and Glenn Frey", Eagles Online Central, retrieved June 5, 2013

- Albano, Ric (November 29, 2012). "The Eagles". Classic Rock Review. Retrieved June 5, 2013.

- Tate 2007, p. 6

- Mowatt, Todd. "In the Game: Nintendo's Shigeru Miyamoto". Amazon. Archived from the original on December 20, 2007. Retrieved September 25, 2006.

- Carlson, Jen (October 9, 2014). "RIP Zelda, The Turkey Of Battery Park". Gothamist. Archived from the original on October 10, 2014. Retrieved June 5, 2013.

- Carlson, Jen (October 30, 2012). "Zelda, The Wild Turkey Of Battery Park, Survived The Storm". Gothamist. Archived from the original on October 11, 2014. Retrieved June 5, 2013.

- Cline 2003, p. 2

- Newton 2005

- Quoted in Tavernier-Courbin 1979, p. 23

- Davis 1995, p. 327

- Tavernier-Courbin 1979, p. 23

- Tavernier-Courbin 1979, p. 22

- Wood 1992, p. 247

- Kakutani 1991

- Bryer, Jackson R. "The critical reputation of F. Scott Fitzgerald." In Prigozy 2002, pp. 227–233.

- Cline 2003, p. 6

- Adair 2005

- "Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald (1900–1948)". Alabama Women's Hall of Fame. State of Alabama. Retrieved February 20, 2012.

References

- Adair, Everl (Spring 2005), "The Art of Zelda Fitzgerald", Alabama Heritage, University of Alabama, no. 76

- Bruccoli, Matthew Joseph (2002) [1981], Some Sort of Epic Grandeur: The Life of F. Scott Fitzgerald (2nd rev. ed.), Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, ISBN 1-57003-455-9

- Bryer, Jackson R.; Barks, Cathy W., eds. (2002), Dear Scott, Dearest Zelda: The Love Letters of F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, New York: St. Martin's Press, ISBN 0-312-26875-0

- Canterbery, E. Ray; Birch, Thomas D. (2006), F. Scott Fitzgerald: Under the Influence, St. Paul, Minnesota: Paragon House, ISBN 1-55778-848-0

- Cline, Sally (2003), Zelda Fitzgerald: Her Voice in Paradise, New York: Arcade Publishing, ISBN 1-55970-688-0

- Curnutt, Kirk, ed. (2004), A Historical Guide to F. Scott Fitzgerald, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-515302-2

- Davis, Simone Weil (1995), "The Burden of Reflecting: Effort and Desire in Zelda Fitzgerald's Save Me the Waltz", Modern Language Quarterly, Duke University Press, 56 (3): 327–362, doi:10.1215/00267929-56-3-327

- Fitzgerald, F. Scott (April 2003) [1945], Wilson, Edmund (ed.), The Crack-Up, New Directions

- Kakutani, Michiko (August 20, 1991), "Books of The Times; That Other Fitzgerald Could Turn a Word, Too", The New York Times, retrieved May 26, 2008

- Ludwig, Arnold M. (1995), The Price of Greatness: Resolving the Creativity and Madness Controversy, Guilford Press, ISBN 978-0-89862-839-5

- Mangum, Bryant (2016), "An Affair of Youth: In Search of Flappers, Belles, and the First Grave of the Fitzgeralds", Broad Street Magazine: 27–39. Republished online summer 2017.

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Milford, Nancy (1970), Zelda: A Biography, New York: Harper & Row, ISBN 9780062089397

- Mizener, Arthur (January 15, 1951), "F. Scott Fitzgerald's Tormented Paradise", Life, p. 93

- Newton, Wesley Phillips (Spring 2005), "F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald Museum", Alabama Heritage, University of Alabama, no. 76

- Pike, Deborah (2017), The Subversive Art of Zelda Fitzgerald, Columbia: University of Missouri Press, ISBN 978-0-8262-2104-9, OCLC 951158302

- Skeel, Sharon. (2020), Catherine Littlefield: A Life in Dance, Oxford University Press. www.catherinelittlefield.com

- Prigozy, Ruth, ed. (2002), The Cambridge Companion to F. Scott Fitzgerald, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-62447-9

- Tate, Mary Jo (2007), Critical Companion to F. Scott Fitzgerald: A Literary Reference to His Life and Work, Infobase Publishing, p. 6, ISBN 978-1-4381-0845-2

- Tavernier-Courbin, Jacqueline (1979), "Art as Woman's Response and Search: Zelda Fitzgerald's Save Me the Waltz", Southern Literary Journal, University of North Carolina Press, 11 (2): 22–42, JSTOR 20077612

- Wood, Mary E. (1992), "A Wizard Cultivator: Zelda Fitzgerald's Save Me the Waltz as Asylum Autobiography", Tulsa Studies in Women's Literature, University of Tulsa, 11 (2): 247–264, doi:10.2307/464300, JSTOR 464300

- Wilson, Edmund (2007) [1952], Dabney, Lewis M. (ed.), Literary Essays and Reviews of the 1920s & 30s: The Shores of Light / Axel's Castle / Uncollected Reviews, New York: Library of America, ISBN 978-1-59853-013-1

- Young, Perry Deane (January 14, 1979), "This Side of Rockville", The Washington Post, retrieved September 3, 2019

Further reading

- Mackrell, Judith. Flappers: Six Women of a Dangerous Generation. 2013. ISBN 978-0-330-52952-5

External links

Media related to Zelda Fitzgerald at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Zelda Fitzgerald at Wikimedia Commons- "Zelda Fitzgerald", Encyclopedia of Alabama