Crosby Hall

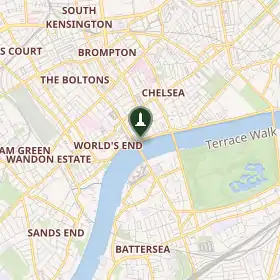

Crosby Hall est un bâtiment historique de Londres édifié en 1466 à Bishopsgate, dans la Cité de Londres. puis déplacé en 1910 vers son site actuel de Cheyne Walk à Chelsea. Entre 1988 et 2021, il est restauré et forme une partie d'une résidence privée sous le nom de Crosby Moran Hall. Ce monument est classé Grade II.

| Fondation | |

|---|---|

| Patrimonialité |

Monument classé de Grade II* (d) () |

| Adresse |

|---|

| Coordonnées |

51° 28′ 57″ N, 0° 10′ 22″ O |

|---|

Histoire

Construction

Crosby Hall est la seule partie préservée du manoir médiéval de Crosby Place, Bishopsgate, dans la Cité de Londres[1]. La construction commence en 1466[2] et se poursuit jusqu'en 1472[1].

En 1910, Crosby Hall est déplacé sur son site actuel de Chelsea[3],[4]. Des modifications conçues par Walter Godfrey sont alors ajoutées[5],[6] et la duchesse d'York inaugure le bâtiment en 1926[7].

Première Guerre mondiale

Pendant la Première Guerre mondiale, Crosby Hall héberge des réfugiés belges aidés par le Chelsea War Refugee Committee[8], et organise des concerts pour recueillir des fonds[9].

Résidence universitaire de la British Federation of University Women

La British Federation of University Women devient locataire de Crosby Hall et fait construire une aile résidentielle en 1925–1927[6],[10]. La résidence est destinée aux boursières des différentes associations de femmes diplômées d'université séjournant à Londres pour leurs recherches[11].

À partir des années 1930 et pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale, Crosby Hall soutient des universitaires allemandes réfugiées en Angleterre, notamment Emmy Klieneberger-Nobel, Betty Heimann, Helen Rosenau[12], Adelheid Heimann, Gertrud Kornfeld (en), Dora Ilse (en) et Erna Hollitscher[11],[13].

Restauration et résidence privée

Le Greater London Council met en vente Crosby Hall qui est acheté en 1988 par l'homme d'affaires Christopher Moran[14].

Références

- (en) Cet article est partiellement ou en totalité issu de l’article de Wikipédia en anglais intitulé « Crosby Hall, London » (voir la liste des auteurs).

- « The history of Crosby Place | British History Online », www.british-history.ac.uk (consulté le )

- « Crosby Hall Palace of Richard III: London coffee houses and taverns », londontaverns.co.uk (consulté le )

- (en) Emma Magnus, « The huge London mansion that was literally moved brick by brick across the city », MyLondon, (consulté le )

- Andrew Saint, « Ashbee, Geddes, Lethaby and the Rebuilding of Crosby Hall », Architectural History, vol. 34, , p. 206–223 (ISSN 0066-622X, DOI 10.2307/1568600, lire en ligne)

- Godfrey 1913.

- Clive Aslet, « Building the past », sur Country Life, (consulté le )

- Carol Dyhouse, « The British Federation of University Women and the status of women in universities, 1907–1939 », Women's History Review, vol. 4, no 4, , p. 465-485 (ISSN 0961-2025, DOI 10.1080/09612029500200093)

- James, « Refugees in Chelsea », Times Literary Supplement, no 740, , p. 133–34 (lire en ligne)

- « Remembering the First World War: Home Front – Library », www.library.qmul.ac.uk (consulté le )

- Simon Thurley, « Crosby Hall – 'the most important surviving domestic Medieval building in London' », Country Life, (consulté le )

- Christine von Oertzen, Science, gender, and internationalism: women's academic networks, 1917–1955, 1st, , 6–8,40–43,127–151 (ISBN 978-1-137-43890-4, lire en ligne)

- (en) Jannik Sachweh, « Helen Rosenau, Aspiring Art Historian and Archaeologist », sur Key Documents of German-Jewish History, .

- « Aid to Refugees », University Women's International Networks Database (consulté le )

- « Dr. Christopher Moran, Chairman of Co-operation Ireland », sur christophermoran.org, (consulté le )

Voir aussi

Bibliographie

- W. Foster, « The East India Company at Crosby House, 1621–38 », London Topographical Record, vol. 8, , p. 106-39

- Walter H. Godfrey, « Crosby Hall and its re-erection », Transactions of the Ancient Monuments Society, vol. 26, , p. 227–43

- Walter H. Godfrey, Chelsea, Pt. II, vol. 4, London, coll. « Survey of London », , 15–17 p., « Crosby Hall (re-erected) »

- Charles William Frederick Goss, Crosby Hall: A Chapter in the History of London, London, Crowther & Goodman, (lire en ligne)

- London, vol. 1, London, Charles Knight, , 317–32 p., « Crosby Place »

- Philip Norman, « Crosby Place », London Topographical Record, vol. 6, , p. 1–22

- Philip Norman et W. D. Caröe, Crosby Place, vol. 9, London, coll. « Survey of London Monograph », (lire en ligne)

- Andrew Saint, « Ashbee, Geddes, Lethaby and the Rebuilding of Crosby Hall », Architectural History, vol. 34, , p. 206–23 (DOI 10.2307/1568600, JSTOR 1568600)

- Rosemary Sweet, « The preservation of Crosby Hall, c.1830–1850 », Historical Journal, vol. 60, no 3, , p. 687-719 (DOI 10.1017/S0018246X15000564)

- Simon Thurley, « Crosby Hall.'the most important surviving domestic medieval building in London », Country Life, vol. 197, no 40, , p. 72–75.

Liens externes

- Ressource relative à l'architecture :

- Ressource relative à la musique :

- Portail du Royaume-Uni

- Portail des femmes et du féminisme

- Portail des universités