Illumination in a Gothic World

The Gothic period, which generally saw an increase in the production of illuminated manuscripts, also saw more secular works such as chronicles and works of literature illuminated. Wealthy people began to build up personal libraries. Philip the Bold probably had the largest personal library of his time in the mid-15th century; he is estimated to have had about 600 illuminated manuscripts, while a number of his friends and relations had several dozen.

Monastic Production of Luxury Books

During the early to mid 1400s, illuminated books were considered a higher art form than panel painting. While they had traditionally been created in monasteries, by the 12th century levels of demand led to their production in specialist workshops known in French as libraires. The works included religious works such the books of hours and prayer books, but also histories, tales of adventure and love, poetry, and a wide range of moralizing works that we might classify as self-improvement books today.

Urban Scriptoria

By the 14th century, the production of luxury manuscripts by monks writing in the monastic scriptorium had almost fully given way to commercial urban scriptoria, especially in Paris, Rome, and Burgundy. While the process of creating an illuminated manuscript did not change, the move from monasteries to commercial settings was a radical step. Demand for manuscripts grew to such an extent that the monastic libraries were unable to meet with the demand, and began employing secular scribes and illuminators. These individuals often lived close to the monastery and, in certain instances, dressed as monks whenever they entered the monastery, but were allowed to leave at the end of the day. In reality, illuminators were often well-known and acclaimed and many of their identities have survived.

At the time illuminated manuscripts were considered treasured works of high craft; to own books indicated wealth, status, and taste. In addition, they became common as diplomatic gifts, or offerings to commemorate dynastic marriages. Paris was the major source of supply after their production spread from the monasteries. However, its importance was supplanted in the 1440s by the cities of Bruges and Ghent, in part due to the patronage of the cultured Philip the Good, who by his death had collected over 1,000 individual books. When in the early to mid-15th century manuscripts were held in higher regard than panel paintings, masters would often produce single leaf illustrations to be almost randomly inserted into precious books, as a means for the master to display and advertise his skill.

Outstanding Illuminators

Simon Marmion was perhaps the best known and most successful artist specializing in this area, although van Eyck is thought to have contributed to the Turin-Milan Hours as the anonymous artist known as Hand G. A number of illustrations from the period show a strong stylistic resemblance to the work of Gerard David, though it is unclear whether they are by his hand or by his followers. There was considerable overlap between panel painting and illumination, and by the second half of the century large manuscript commissions were often shared between several different masters, with more junior painters, including many women, assisting, especially in producing the increasingly elaborate border decoration.

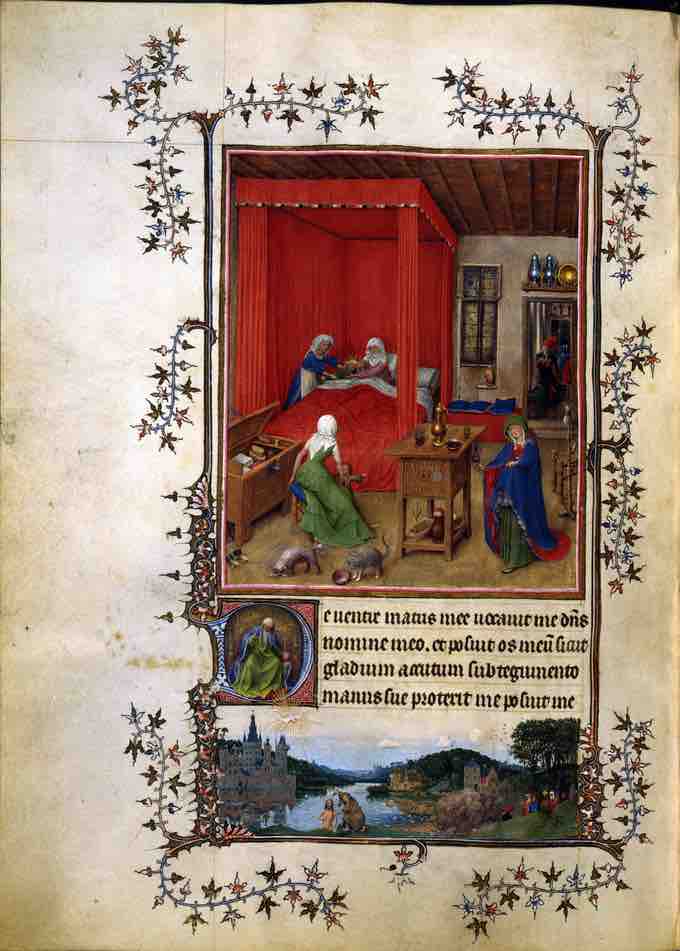

Page from the "Turin-Milan Hours," anonymous artist known as Hand G.

The Birth of John the Baptist (above) and the Baptism of Christ below, by "Hand G," Turin.