Allopatric Speciation

A geographically-continuous population has a gene pool that is relatively homogeneous. Gene flow, the movement of alleles across the range of the species, is relatively free because individuals can move and then mate with individuals in their new location. Thus, the frequency of an allele at one end of a distribution will be similar to the frequency of the allele at the other end. When populations become geographically discontinuous, that free-flow of alleles is prevented. When that separation continues for a period of time, the two populations are able to evolve along different trajectories. This is known as allopatric speciation. Thus, their allele frequencies at numerous genetic loci gradually become more and more different as new alleles independently arise by mutation in each population. Typically, environmental conditions, such as climate, resources, predators, and competitors for the two populations will differ causing natural selection to favor divergent adaptations in each group.

Isolation of populations leading to allopatric speciation can occur in a variety of ways: a river forming a new branch, erosion forming a new valley, a group of organisms traveling to a new location without the ability to return, or seeds floating over the ocean to an island. The nature of the geographic separation necessary to isolate populations depends entirely on the biology of the organism and its potential for dispersal. If two flying insect populations took up residence in separate nearby valleys, chances are individuals from each population would fly back and forth, continuing gene flow. However, if two rodent populations became divided by the formation of a new lake, continued gene flow would be improbable; therefore, speciation would be probably occur.

Biologists group allopatric processes into two categories: dispersal and vicariance. Dispersal occurs when a few members of a species move to a new geographical area, while vicariance occurs when a natural situation arises to physically divide organisms.

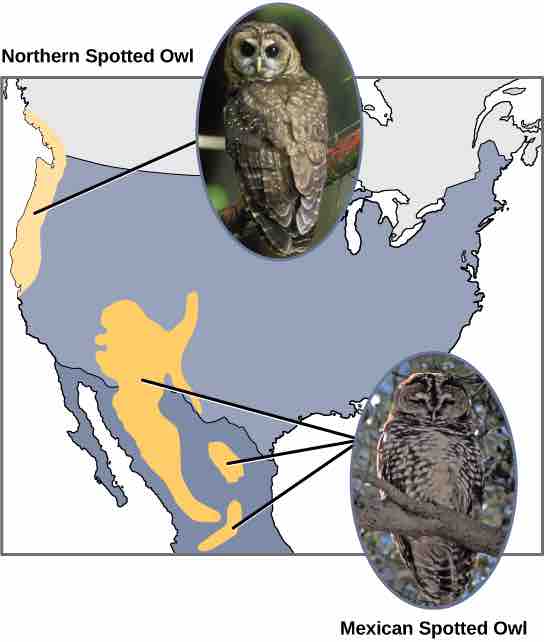

Scientists have documented numerous cases of allopatric speciation. For example, along the west coast of the United States, two separate sub-species of spotted owls exist. The northern spotted owl has genetic and phenotypic differences from its close relative, the Mexican spotted owl, which lives in the south .

Allopatric speciation due to geographic separation

The northern spotted owl and the Mexican spotted owl inhabit geographically separate locations with different climates and ecosystems. The owl is an example of allopatric speciation.

Additionally, scientists have found that the further the distance between two groups that once were the same species, the more probable it is that speciation will occur. This seems logical because as the distance increases, the various environmental factors would generally have less in common than locations in close proximity. Consider the two owls: in the north, the climate is cooler than in the south causing the types of organisms in each ecosystem differ, as do their behaviors and habits. Also, the hunting habits and prey choices of the southern owls vary from the northern owls. These variances can lead to evolved differences in the owls, resulting in speciation.

Adaptive Radiation

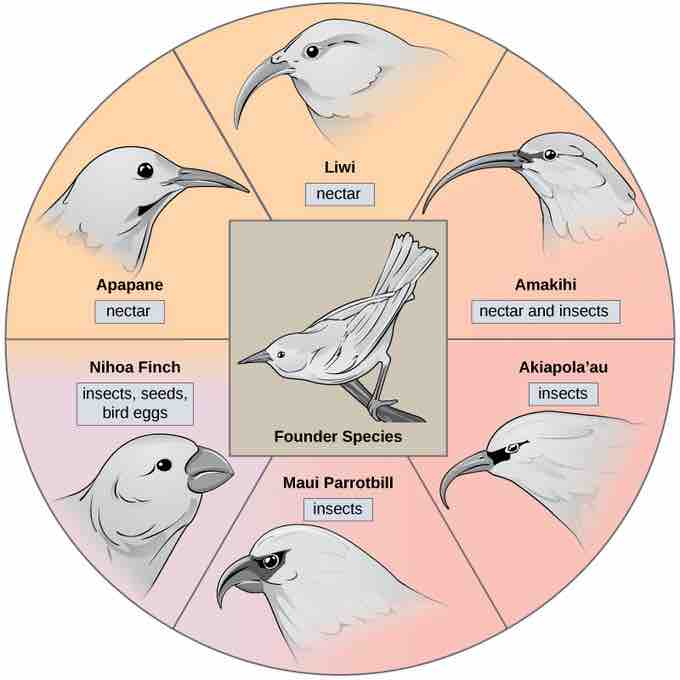

In some cases, a population of one species disperses throughout an area with each finding a distinct niche or isolated habitat. Over time, the varied demands of their new lifestyles lead to multiple speciation events originating from a single species. This is called adaptive radiation because many adaptations evolve from a single point of origin, causing the species to radiate into several new ones. Island archipelagos like the Hawaiian Islands provide an ideal context for adaptive radiation events because water surrounds each island which leads to geographical isolation for many organisms. The Hawaiian honeycreeper illustrates one example of adaptive radiation. From a single species, called the founder species, numerous species have evolved .

Adaptive Radiation

The honeycreeper birds illustrate adaptive radiation. From one original species of bird, multiple others evolved, each with its own distinctive characteristics.

In Hawaiian honeycreepers, the response to natural selection based on specific food sources in each new habitat led to the evolution of a different beak suited to the specific food source. The seed-eating birds have a thicker, stronger beak which is suited to break hard nuts. The nectar-eating birds have long beaks to dip into flowers to reach the nectar. The insect-eating birds have beaks like swords, appropriate for stabbing and impaling insects.