The trachea, or windpipe, is a tube that connects the pharynx or larynx to the lungs, allowing the passage of air. It is lined with pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium cells with goblet cells that produce mucus. The trachea is part of the conducting zone for air into and out of the lungs.

The trachea

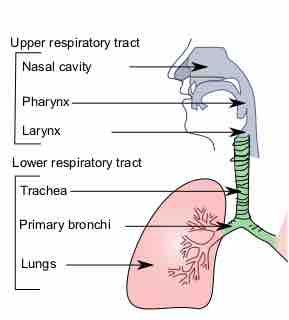

This is the trachea in relation to the rest of the respiratory system.

Anatomy of the Trachea

The trachea is a long tube that extends from the pharynx and larynx to the bronchi of the lungs. It typically has an inner diameter of about 25.4 millimeters (1.00 in) and a length of about 10 to 16 centimeters.

The trachea commences at the lower border of the larynx, level with the sixth cervical vertebra, and bifurcates into the primary bronchi at the vertebral level of thoracic vertebra T5, or up to two vertebrae lower or higher, depending on breathing.

At the top of the trachea and bottom of the larynx is the cricoid cartilage, the only complete ring of cartilage in the trachea. Extending downward throughout the length of the tube are about fifteen to 20 C-shaped cartilaginous rings that reinforce the outer structure and shape of the trachea—the open part of each C-shaped ring reveals a membranous wall on the inside of the trachea.

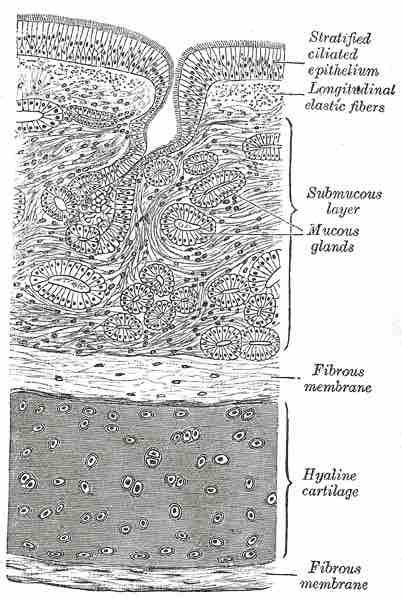

The cartilage of the trachea is considered hyaline cartilage: simple, transparent, and made primarily of collagen. The trachealis muscle connects the open ends of the C-shaped rings of cartilage and contracts during coughing, reducing the size of the lumen of the trachea to increase the air flow rate.

The esophagus lies behind the trachea. The C-shaped cartilaginous rings allow the trachea to collapse slightly at its opening, so food can pass down the esophagus after swallowing.

The epiglottis closes the opening to the larynx during swallowing to prevent swallowed matter from entering the trachea.

Histology of the Trachea

A cross section of the trachea, showing the hyaline cartilage, mucus glands, and ciliated epithelium.

Physiology of the Trachea

This mucus and cilia of the trachea form the mucociliary escalator, which lines the cells of the trachea with mucus to trap inhaled foreign particles. The cilia then waft upward toward the larynx and the pharynx, where it can be either swallowed into the stomach (and destroyed by acid) or expelled as phlegm.

The mucociliary escalator is one of the most important functions of the trachea and is also considered a barrier component of the immune system due its role in preventing pathogens from entering the lungs. The epithelium and the mucociliary ladder can be damaged by smoking tobacco and alcohol consumption, which can make pneumonia (an infection of the alveoli of the lungs) from bacteria in the upper respiratory tract more likely to occur due to the loss of barrier function.

As a part of the conducting zone of the lungs, the trachea is important in warming and moistening air before it reaches the lungs. The trachea is also considered a part of normal anatomical dead space (space in the airway that isn't involved in alveolar gas exchange) and its volume contributes to calculations of ventilation and physiological (total) dead space. It is not considered alveolar dead space, a term that refers to alveoli that don't partake in gas exchange due to damage or lack of blood supply.